From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

80 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

CASE STUDY

“Tom” is a 23-year-old, single, white male who

present- ed for treatment approximately 1 year

after a traumatic event that occurred during his

military service in Iraq. Tom received CPT while

on active duty in the Army.

Background

Tom was born the third of four children to his

parents. He described his father as an alcoholic

who was frequently absent from the home due to

work travel prior to his parents’ divorce. Tom

indicated that his father was always emotionally

distant from the family, especially after the

divorce. Tom had close relationships with his

mother and siblings. He denied having any

significant mental health or physical health

problems in his childhood. However, he described

two significant traumatic events in his

adolescence. Specifically, he described witnessing

his best friend commit suicide by gunshot to the

head. Tom indicated that this event severely

affected him, as well as his entire community. He

went on to report that he still felt responsible for

not preventing his friend’s suicide. The second

traumatic event was the death of Tom’s brother in

an automobile accident when Tom was 17 years

old. Tom did not receive any mental health

treatment during his childhood or after these

events, though he indicated that he began using

alcohol and illicit substances after these traumatic

events in his youth. He admitted to using

cannabis nearly daily during high school, as well

as daily use of alcohol, drinking as much as a 24-

pack of beer per day until he passed out. Tom

reported that he decreased his alcohol

consumption and ceased using cannabis after his

enlistment.

Tom served in the Infantry. He went to Basic

Training, then attended an advanced training

school prior to being deployed directly to Iraq.

While in Iraq, Tom witnessed and experienced a

number of traumatic incidents. He spoke about

fellow soldiers who were killed and injured in

service, as well as convoys that he witnessed

being hit by improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

However, the traumatic event that he identified

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

81

as most distressing and anxiety-provoking was shoot-

ing a pregnant woman and child.

Tom described this event as follows: Suicide bomb-

ers had detonated several bombs in the area where Tom

served, and a control point had been set up to contain

the area. During the last few days of his deployment,

Tom was on patrol at this control point. It was dark out-

side. A car began approaching the checkpoint, and of-

ficers on the ground signaled for the car to stop. The car

did not stop in spite of these warnings. It continued to

approach the control point, entering the area where the

next level of Infantrymen were guarding the entrance.

Per protocol, Tom fired a warning shot to stop the ap-

proaching car, but the car continued toward the control

point. About 25 yards from the control point gate, Tom

and at least one other soldier fired upon the car several

times.

After a brief period of disorientation, a crying man

with clothes soaked with blood emerged from the car

with his hands in the air. The man quickly fell to his

knees, with his hands and head resting on the road.

Tom could hear the man sobbing. According to Tom,

the sobs were guttural and full of despair. Tom looked

over to find in the pedestrian seat a dead woman who

was apparently pregnant. A small child in the backseat

was also dead. Tom never confirmed this, but he and

his fellow soldiers believed that the man crying on the

road was the husband of the woman and the father of

the child and fetus.

Tom was immediately distressed by the event, and a

Combat Stress Control unit in the field eventually had

him sent back to a Forward Operating Base because

of his increasing reexperiencing and hypervigilance

symptoms. Tom was eventually brought to a major

Army hospital and received individual CPT within this

setting.

Tom was administered the CAPS at pretreatment;

his score was in the severe range, and he met diagnostic

criteria for PTSD. He also completed the Beck Depres-

sion Inventory–II (BDI-II) and the State–Trait Anxiety

Inventory (STAI). His depression and anxiety symp-

toms at pretreatment were in the severe range. Tom was

provided feedback about his assessment results in a

session focused on an overview of his psychological as-

sessment results and on obtaining his informed consent

for a course of CPT. After providing feedback about

his assessment, the therapist gave Tom an overview of

CPT, with an emphasis on its trauma-focused nature,

expectation of out-of-session practice adherence, and

the client’s active role in getting well. Tom signed a

“CPT Treatment Contract” detailing this information

and was provided a copy of the contract for his records.

The CPT protocol began in the next session.

Session 1

Tom arrived 15 minutes prior to his first scheduled ap-

pointment of CPT. He sat down in the chair the therapist

gestured that he sit in, but he was immediately restless

and repositioned frequently. Tom quickly asked to move

to a different chair in the room, so that his back was

not facing the exterior door and his gaze could monitor

both the door and the window. He asked the therapist

how long his session would take and whether he would

have to “feel anything.” The therapist responded that

this session would last 50–60 minutes, and that, com-

pared with other future sessions, she would be doing

most of the talking. She added that, as discussed during

the treatment contracting session, the focus would be

on Tom’s feelings in reaction to the traumatic event but

that the current session would focus less on this. The

therapist also explained that she would have the treat-

ment manual in her lap, and would refer to it throughout

to make sure that she delivered the psychotherapy as it

was prescribed. She encouraged Tom to ask any ques-

tions he might have as the session unfolded.

The therapist explained that at the beginning of each

session they would develop an agenda for the session.

The purposes of the first therapy session were to (1)

describe the symptoms of PTSD; (2) give Tom a frame-

work for understanding why these symptoms had not

remitted; (3) present an overview of treatment to help

Tom understand why practice outside of session and

therapy attendance were important to elicit cooperation

and to explain the progressive nature of the therapy; (4)

build rapport between Tom and the therapist; and (5)

give the client an opportunity to talk briefly about his

most distressing traumatic event or other issues.

The therapist then proceeded to give didactic infor-

mation about the symptoms of PTSD. She asked Tom

to provide examples of the various clusters of PTSD

symptoms that he was experiencing, emphasizing how

reexperiencing symptoms are related to hyperarousal

symptoms, and how hyperarousal symptoms elicit a

desire to avoid or become numb. The paradoxical ef-

fect of avoidance and numbing in maintaining, or even

increasing, PTSD symptoms was also discussed. Tom

indicated that this was the first time someone had ex-

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

82 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

plained the symptoms of PTSD in this way, putting

them “in motion” by describing how they interact with

one another.

The therapist transitioned to a description of trauma

aftereffects within an information-processing frame-

work. She described in lay terms how traumas may be

schema-discrepant events; traumatic events often do

not fit with prior beliefs about oneself, others, or the

world. To incorporate this event into one’s memory,

the person may alter his/her perception of the event

(assimilate the event into an existing belief system).

Examples of assimilation include looking back on the

event and believing that some other course of action

should have been taken (“undoing” the event) or blam-

ing oneself because it occurred. The therapist went

on to explain that Tom could have also attempted to

change his prior belief system radically to overaccom-

modate the event to his prior beliefs. “Overaccommo-

dation” was described as changing beliefs too much as

a result of the traumatic event (e.g., “I can’t trust myself

about anything”). She explained that several areas of

beliefs are often affected by trauma, including safety,

trust, power/control, esteem, and intimacy. She further

explained that these beliefs could be about the self and/

or others. The therapist also pointed out that if Tom had

negative beliefs prior to the traumatic event relative to

any of these topics, the event could serve to strengthen

these preexisting negative beliefs.

At this point, Tom described his childhood and ado-

lescent experiences, and how they had contributed to

his premilitary trauma beliefs. The therapist noted that

Tom tended to blame himself and to internalize the bad

things that had happened in his family and the suicide

of his friend. She also noted his comment, “I wonder if

my father drank to cope with me and my siblings.” In

Tom’s case, it seemed likely that the traumatic experi-

ence served more to confirm his preexisting beliefs that

he had caused or contributed to bad things happening

around and to him.

Tom then spent some time describing how drasti-

cally things had changed after his military traumas.

Prior to his military experiences and, specifically, the

shooting of the woman and child, Tom described him-

self as “proud of being a soldier” and “pulling his life

together.” He indicated that the military structure had

been very good for him in developing self-discipline

and improving his self-esteem. He indicated that he

felt good about “the mission to end terrorism” and was

proud to serve his country. He felt camaraderie with his

fellow soldiers and considered a career in the military.

He denied any authority problems and in fact believed

that his commanding officers had been role models

of the type of leader he wished to be. Prior to his de-

ployment to Iraq, Tom met and married his wife, and

they appeared to have a stable, intimate relationship.

After his return from Iraq, Tom indicated that he did

not trust anyone, especially anyone associated with the

U.S. government. Tom expressed his disillusionment

with the war effort and distrust of the individuals who

commanded his unit. He also articulated distrust of

himself: “I always make bad decisions when the chips

are down.” He stated that he felt completely unsafe in

his environment. In his immediate postdeployment pe-

riod, Tom had occasionally believed snipers on the base

grounds had placed him in their crosshairs to kill him.

He indicated that he minimally tolerated being close

to his wife, including sexual contact between the two

of them.

The therapist introduced the notion of “stuck points,”

or ways of making sense of the trauma or of thinking

about himself, others, and the world, as getting in the

way of Tom’s recovery from the traumatic events. The

therapist noted that a large number of individuals are

exposed to trauma. In fact, military personnel are

among the most trauma-exposed individuals. However,

most people recover from their trauma exposure. Thus,

a primary goal of the therapy was to figure out what had

prevented Tom from recovering (i.e., how his thinking

had got him “stuck,” leading to the maintenance of his

PTSD symptoms).

The therapist then asked Tom to provide a 5-minute

account of his index traumatic event. Tom immediately

responded, “There were so many bad things over there.

How could I pick one?” The therapist asked, “Which of

those events do you have the most thoughts or images

about? Which of those events do you dislike thinking

about the most?” The therapist indicated that Tom did

not need to provide a fine-grained description of the

event, but rather a brief overview of what happened.

Tom provided a quick account of the shooting of the

woman and child. The therapist praised Tom for shar-

ing about the event with her and asked about his feel-

ings as a result of sharing the information. Tom said

that he felt anxious and wanted the session to be over.

The therapist used this as an opportunity to describe

the differences between “natural” and “manufactured”

emotions.

The therapist first described “natural” emotions as

those feelings that are commensurate reactions to expe-

riences that have occurred. For example, if we perceive

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

83

that someone has wronged us, it is natural to feel anger.

If we encounter a threatening situation, it is natural to

feel fear. Natural emotions have a self-limited and di-

minishing course. If we allow ourselves to feel these

natural emotions, they will naturally dissipate. The

therapist used the analogy of the energy contained in

a bottle of carbonated soda to illustrate this concept.

If the top of the bottle is removed, the pressure ini-

tially comes out with some force, but that force sub-

sides and eventually has no energy forthcoming. On

the other hand, there are “manufactured” emotions,

or emotions that a person has a role in making. Our

thoughts contribute to the nature and course of these

emotions. The more that we “fuel” these emotions with

our self-statements, the more we can increase the “pres-

sure” of these emotions. For example, if a person tells

himself over and over that he is a stupid person and

reminds himself of more and more situations in which

he perceived that he made mistakes, then he is likely to

have more and more anger toward himself. The thera-

pist reiterated that the goals of the therapy were (1) to

allow Tom to feel the natural emotions he has “stuffed,”

which keep him from recovering from his trauma; and

(2) to figure out how Tom was manufacturing emotions

that were unhelpful to him.

The therapist summarized for Tom the three major

goals of the therapy: (1) to remember and to accept

what happened to him by not avoiding those memories

and associated emotions; (2) to allow himself to feel his

natural emotions and let them run their course, so the

memory could be put away without such strong feelings

still attached; and (3) to balance beliefs that had been

disrupted or reinforced, so that Tom did not manufac-

ture unhelpful emotions.

The therapist made a strong pitch for the importance

of out-of-session practice adherence before assigning

Tom the first practice assignment. The therapist told

Tom that there appeared to be no better predictor of

response to the treatment than how much effort a pa-

tient puts into it. She pointed out that of the 168 hours

in a week, Tom would be spending 1–2 hours of that

week in psychotherapy sessions (Note. We have found

it helpful to do twice-weekly sessions, at least in the

initial portion of the therapy, to facilitate rapport build-

ing, to overcome avoidance, and to capitalize on early

gains in the therapy.) If Tom only spent the time dur-

ing psychotherapy sessions focused on these issues, he

would be spending less than 1% of his week focused

on his recovery. To get better, he would be using daily

worksheets and other writing assignments to promote

needed skills in his daily life and to decrease his avoid-

ance. The therapist also pointed out that at the begin-

ning of each session they would review the practice as-

signments that Tom had completed. The therapist asked

Tom if this made sense, and he responded, “Sure. It

makes sense that you get out of it what you put into it.”

Tom’s first assignment was to write an Impact State-

ment about the meaning of the event to determine how

he had made sense of the traumatic event, and to help

him begin to determine what assimilation, accommo-

dation, and overaccommodation had occurred since

the event. Stuck points that get in the way of recovery

are identified with this first assignment. Tom was in-

structed to start writing the assignment later that day

to address directly any avoidance about completing the

assignment. He was specifically reminded that this was

not a trauma account (that would come later) and that

this assignment was specifically designed to get at the

meaning of the event in his life, and how it had im-

pacted his belief systems.

The specific assignment was as follows:

Please write at least one page on what it means to

you that you that this traumatic experience happened.

Please consider the effects that the event has had on

your beliefs about yourself, your beliefs about others,

and your beliefs about the world. Also consider the fol-

lowing topics while writing your answer: safety, trust,

power/competence, esteem, and intimacy. Bring this

with you to the next session.

Session 2

The purposes of the second session are (1) to discuss

the meaning of the event and (2) to help Tom begin to

recognize thoughts, label emotions, and see the con-

nection between what he says to himself and how he

feels. Tom arrived with obvious anger and appeared

defensive throughout most of the session. He stated

that he had been feeling quite angry all week, and that

he was “disgusted” with society and particularly poli-

ticians, who were “all self-interested or pandering to

those with money.” He expressed a great deal of anger

over the reports of alleged torture at Abu Ghraib pris-

on, which was a major news item during his therapy.

The therapist was interested in the thinking behind

Tom’s anger about the events at Abu Ghraib. However,

she first reviewed Tom’s practice assignment, writing

the first Impact Statement, to reinforce the completion

of this work and to maintain the session structure she

had outlined in the first session.

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

84 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

The therapist asked Tom to read his Impact State-

ment aloud. Clients in individual CPT are always asked

to read their practice assignments aloud. Should the

therapist read them, the client could dissociate or oth-

erwise avoid his/her own reactions to their material.

Tom had written:

The reason that this traumatic event happened is be-

cause I was friggin’ stupid and made a bad decision.

I killed an innocent family, without thinking. I mur-

dered a man’s wife and child. I can’t believe that I did

it. I took that man’s wife and child, and oh, yeah, his

unborn child, too. I feel like I don’t deserve to live, let

alone have a wife and child on the way. Why should I be

happy when that man was riddled with despair, and that

innocent woman, child, and unborn child died? Now, I

feel like I’m totally unsafe. I don’t feel safe even here

on the hospital grounds, let alone in the city or back

home with my family. I feel like someone is watching

me and is going to snipe at me and my family because

the terrorists had information about the situation and

passed it on. I also don’t feel that people are safe around

me. I might go off and hurt someone, and God forbid

it be my own family. With my wife pregnant, I am re-

ally concerned that I might hurt her. I don’t trust any-

one around me, and especially the government. I don’t

even trust the military treating me. I also don’t trust

myself. If I made a bad decision at that time, who is

to say that I won’t make a bad decision again? About

power and control, I feel completely out of control of

myself, and like the military and my commanding of-

ficer have complete control over me. My self-esteem is

in the toilet. Why wouldn’t it be given the crappy things

that I have done? I don’t think there are many positive

things that I’ve done with my life, and when the chips

are down, I always fail and let others down. I’m not sure

what other-esteem is, but I do like my wife. In fact, I

don’t think she deserves to have to deal with me, and I

think they would be better without me around. I don’t

want to be close to my wife, or anyone else for that mat-

ter. It makes me want to crawl out of my skin when my

wife touches me. I feel like I’ll never get over this. It

wasn’t supposed to be like this.

The therapist asked Tom what it was like to write and

then read the Impact Statement aloud. Tom responded

that it had been very difficult, and that he had avoided

the assignment until the evening before his psycho-

therapy session. The therapist immediately reinforced

Tom for his hard work in completing the assignment.

She also used the opportunity to gently address the

role of avoidance in maintaining PTSD symptoms. She

asked specific Socratic questions aimed at elucidating

the distress associated with anticipatory anxiety, and

wondered aloud with Tom about what it would have

been like to have completed the assignment earlier in

the week. She also asked Socratic questions aimed at

highlighting the fact that Tom felt better, not worse,

after completing the assignment.

Tom’s first Impact Statement and the information he

shared in the first session made evident the stuck points

that would have to be challenged. In CPT, areas of as-

similation are prioritized as the first targets of treat-

ment. Assimilation is targeted first because changes

in the interpretation of the event itself are integrally

related to the other, more generalized beliefs involved

in overaccommodation. In Tom’s case, he was assimi-

lating the event by blaming himself. He used the term

“murderer” to describe his role in the event, disregard-

ing important contextual factors that surrounded the

event. These beliefs would be the first priority for chal-

lenging. Tom’s overaccommodation is evident in his

general distrust of society and authority figures, and his

belief that he will make bad decisions in difficult situ-

ations. His overaccommodation is also evident in his

sense of threat in his environment (e.g., snipers), dif-

ficulty being emotionally and physically intimate with

his wife, and low esteem for others and himself.

The therapist returned to Tom’s anger about Abu

Ghraib to get a better sense of possible stuck points, and

also to experiment with Tom’s level of cognitive rigid-

ity or openness to cognitive challenging. The following

exchange ensued between Tom and the therapist:

T

HERAPIST: Earlier you mentioned that you were feel-

ing angry about the reports from Abu Ghraib. Can

you tell me what makes you angry?

T

OM: I can’t believe that they would do that to those

prisoners.

T

HERAPIST: What specifically upsets you about Abu

Ghraib?

T

OM: Haven’t you heard the reports? I can’t believe that

they would humiliate and hurt them like that. Once

again, the U.S. military’s use of force is unaccept-

able.

T

HERAPIST: Do you think your use of force as a mem-

ber of the U.S. military was unacceptable?

T

OM: Yes. I murdered innocent civilians. I am no dif-

ferent than those military people at Abu Ghraib. In

fact, I’m worse because I murdered them.

T

HERAPIST: “Murder.” That’s a strong word.

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

85

TOM: Yeah?

T

HERAPIST: From what you’ve told me, it seems like

you killed some people who may or may not have

been “innocent.” Your shooting occurred in a very

specific place and time, and under certain circum-

stances.

T

OM: Yes, they died at my hands.

T

HERAPIST: Yes, they died, and it seems, at least in

part, because of your shooting. Does that make you

a murderer?

T

OM: Innocent people died and I pulled the trigger. I

murdered them. That’s worse than what happened at

Abu Ghraib.

T

HERAPIST: (quietly) Really, you think it is worse?

T

OM: Yes. In one case, people died, and in another they

didn’t. Both are bad, and both were caused by sol-

diers, but I killed people and they didn’t.

T

HERAPIST: The outcomes are different—that is true.

I’m curious if you think how it happened matters?

T

OM: Huh?

T

HERAPIST: Does it matter what the soldiers’ intentions

were in those situations, regardless of the outcome?

T

OM: No. The bottom line is killing versus no killing.

T

HERAPIST: (realizing that there was minimal flexibil-

ity at this point) I agree that there is no changing the

fact that the woman and child died, and that your

shooting had something to do with that. However,

I think we might slightly disagree on the use of the

term “murder.” It is clear that their deaths have been

a very difficult thing for you to accept, and that you

are trying to make sense of that. The sense that you

appear to have made of their deaths is that you are a

“murderer.” I think this is a good example of one of

those stuck points that seem to have prevented you

from recovering from this traumatic event. We’ll

definitely be spending more time together on under-

standing your role in their deaths.

In addition to testing Tom’s cognitive flexibility,

the therapist also wanted to plant the seeds of a dif-

ferent interpretation of the event. She was careful not

to push too far and retreated when it was clear that

Tom was not amenable to an alternative interpretation

at this point in the therapy. He was already defensive

and somewhat angry, and she did not want to exacer-

bate his defensiveness or possibly contribute to dropout

from the therapy.

From there, the therapist described how important it

was to be able to label emotions and to begin to iden-

tify what Tom was saying to himself. The therapist and

Tom discussed how different interpretations of events

can lead to very different emotional reactions. They

generated several examples of how changes in thoughts

result in different feelings. The therapist also reminded

Tom that some interpretations and reactions follow

naturally from situations and do not need to be altered.

For example, Tom indicated that he was saddened by

the death of the family; the therapist did not challenge

that statement. She encouraged Tom to feel his sadness

and to let it run its course. He recognized that he had

lost something, and it was perfectly natural to feel sad

as a result. At this point Tom responded, “I don’t like to

feel sad. In fact, I don’t like to feel at all. I’m afraid I’ll

go crazy.” The therapist gently challenged this belief.

“Have you ever allowed yourself to feel sad?” Tom re-

sponded that he worked very hard to avoid any and all

feelings. The therapist encouraged Tom, “Well, given

that you don’t have much experience with feeling your

feelings, we don’t know that you’re going to go crazy

if you feel your feelings, right?” She also asked him

whether he had noticed anyone in his life who had felt

sad and had not gone crazy. He laughed. The therapist

added, “Not feeling your feelings hasn’t been working

for you so far. This is your opportunity to experiment

with feeling these very natural feelings about the trau-

matic event to see whether it can help you recover now

from what has happened.”

Tom was given a number of A-B-C Sheets as prac-

tice assignments to begin to identify what he was telling

himself and his resulting emotions. In the first column,

under A, “Something happens,” Tom was instructed

to write down an event. Under the middle column, B,

“I tell myself something,” he was asked to record his

thoughts about the event. Under column C, “I feel and/

or do something,” Tom was asked to write down his

behavioral and emotional responses to the event. The

therapist pointed out that if Tom says something to

himself a lot, it becomes automatic. After a while, he

does not need to think the thought consciously, he can

go straight to the feeling. It is important to stop and rec-

ognize automatic thoughts to decide whether they ei-

ther make sense or should be challenged and changed.

Session 3

Tom handed the therapist his practice assignments as

soon as he arrived. The therapist went over the individ-

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

86 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

ual A-B-C Sheets Tom had completed and emphasized

that he had done a good job in identifying his feelings

and recognizing his thoughts. Some of this work is

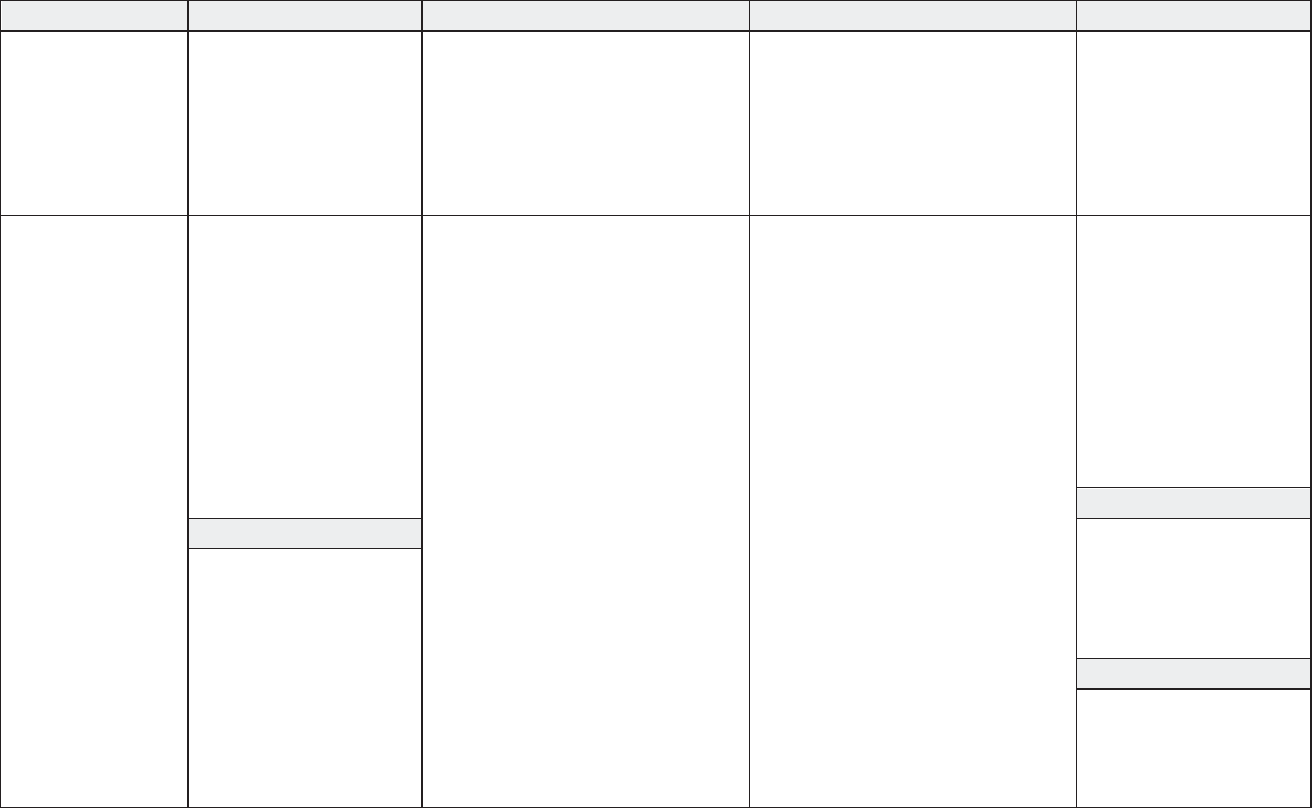

shown in Figure 2.1.

The purpose of reviewing this work at this point in

the therapy is to identify thoughts and feelings, not to

heavily challenge the content of those thoughts. The

therapist did a minor correction of Tom’s identification

of the thought “I feel like I’m a bad person” (bolded

in Figure 2.1) as a feeling. She commented that feel-

ings are almost always one word and what you feel in

your “gut,” and that adding the stem “I feel . . . ” does

not necessarily make it a feeling. The therapist noticed

the pattern of thoughts that Tom tended to record (i.e.,

internalizing and self-blaming), as well as the charac-

teristic emotions he reported.

The therapist noted the themes of assimilation that

again emerged (i.e., self-blame) and chose to focus on

mildly challenging these related thoughts. She specifi-

cally chose to focus on Tom’s thoughts and feelings re-

lated to his wife’s pregnancy, which ultimately seemed

to be related to his assimilation of the traumatic event.

T

HERAPIST: You don’t think you deserve to have a fam-

ily? Can you say more about that?

T

OM: Why should I get to have a family when I took

someone else’s away?

T

HERAPIST: OK, so it sounds like this relates to the first

thought that you wrote down on the A-B-C Sheet

about being a murderer. When you say to yourself, “I

took someone else’s family away,” how do you feel?

T

OM: I feel bad.

T

HERAPIST: Let’s see if we can be a bit more precise.

What brand of bad do you feel? Remember how we

talked about the primary colors of emotion? Which

of those might you feel?

T

OM: I feel so angry at myself for doing what I did.

T

HERAPIST: OK. Let’s write that down—anger at self.

So, I’m curious, Tom, do the other people you’ve told

about this situation, or who were there at the time,

think what you did was wrong?

T

OM: No, but they weren’t the ones who did it, and they

don’t care about the Iraqi people like I do.

ACTIVATING EVENT

A

“Something happens”

BELIEF

B

“I tell myself something”

CONSEQUENCE

C

“I feel something”

I killed an innocent family. “I am a murderer.” I feel like I’m a bad person.

Avoid talking about it.

My wife is pregnant. “I don’t deserve to have a family.” Guilty

Abu Ghraib “The government sucks.” Angry

Going to therapy

“I’m weak. I shouldn’t have PTSD.

PTSD is only for the weak.”

Angry

Are my thoughts in B realistic?

Yes.

What can you tell yourself on such occasions in the future?

?

FIGURE 2.1.

A-B-C Sheet.

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

87

THERAPIST: Hmm . . . that makes me think about some-

thing, Tom. In the combat zone in which you were

involved in Iraq, how easy was it to determine who

you were fighting?

T

OM: Not always particularly easy. There were lots of

insurgents who looked like everyday people.

T

HERAPIST: Like civilians? Innocent civilians? (pause)

T

OM: I see where you are going. I feel like it is still

wrong because they died.

T

HERAPIST: I believe you when you say that it feels that

way. However, feeling a certain way doesn’t neces-

sarily mean that it is based on the facts or the truth.

We’re going to work together on seeing whether that

feeling of guilt or wrongdoing makes sense when we

look at the situation very carefully in our work to-

gether.

Because the goal is for Tom to challenge and dis-

mantle his own beliefs, the therapist probed and plant-

ed seeds for alternative interpretations of the traumatic

event but did not pursue the matter too far. Although

Tom did move some from his extreme stance within the

session, the therapist was not expecting any dramatic

changes. She focused mostly on helping Tom get the

connections among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors,

and developing a collaborative relationship in which

cognitive interventions could be successfully delivered.

The therapist praised Tom for his ability to recog-

nize and label thoughts and feelings, and said that she

wanted Tom to attend to both during the next assign-

ment, which was writing about the index traumatic

event. Tom was asked to write as his practice assign-

ment a detailed account of the event, and to include

as many sensory details as possible. He was asked to

include his thoughts and feelings during the event. He

was instructed to start as soon as possible on the assign-

ment, preferably that day, and to pick a time and place

where he would have privacy and could allow himself

to experience his natural emotions. Wherever he had to

stop writing his account of the event, he was asked to

draw a line. (The place where the client stops is often

the location of a stuck point in the event, where the cli-

ent gave up fighting, where something particularly hei-

nous occurred, etc.) Tom was also instructed to read

the account to himself every day until his next session.

The therapist predicted that Tom would want to avoid

writing the account and procrastinate until as late as

possible. She asked Tom why it would be important for

him to do the assignment and do it as soon as possible.

This was a technique to determine how much Tom

was able to recount the rationale for the therapy, and

to strengthen his resolve to overcome avoidance. Tom

responded that he needed to stop avoiding, or he would

remain scared of his memory. The therapist added that

the assignment was to help Tom get his full memory

back, to feel his emotions about it, and for therapist and

client to begin to look for stuck points. She also reas-

sured Tom that although doing so could be difficult for

a relatively brief period of time, it would not continue

to be so intense, and he would soon be over the hardest

part of the therapy.

Session 4

During the settling-in portion of the session, Tom in-

dicated that he had written the account of the event

the evening before, although he had thought about and

dreaded it every day prior to that. He admitted that he

had been avoidant due to his anxiety. The therapist

asked Tom to read his account aloud to her. Before

starting, Tom asked why it was important to read it in

the session. The therapist reminded Tom of what they

had talked about the previous session, and added that

the act of reading aloud would help him to access the

whole memory and his feelings about it. Tom read what

he wrote quickly, like a police report, and without much

feeling:

There were several of us who were assigned to guard a

checkpoint south of Baghdad. We were there because

insurgents were beginning to take over the particu-

lar area, and we were there to contain the area. I was

placed on top of the checkpoint. It was dusk. It had been

a fairly routine day, with people coming through the

checkpoint like they were going through a toll booth.

Off in the distance I noticed a small, dark car that was

going faster than most cars. I could tell it was going

faster because there was more sand smoke kicking up

behind it. Men out in front of the checkpoint were mo-

tioning for the car to slow down, but it didn’t seem to be

slowing down. Someone shot into the air to warn them,

but they kept on coming. I could see two heads in the

car coming toward us. We had been told to shoot at any

vehicle that came within 25 yards of the gate to protect

those around the gate, and the area beyond the gate.

The car kept coming. I shot a bunch of rounds at the car.

At least one other person shot, too. There was so

much chaos after that. I remember feeling my gun in

my hand as I stood there. After a few moments, I also

remember my legs carrying me down to the car. I don’t

really remember how I got there, but I did. Several men

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

88 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

had surrounded the car, and a man got out of it. The

man was crying. No, sobbing. He was speaking fast

while he cried. He turned toward the car, resisting the

men who attempted to remove him from the scene. I

turned to see what the man was looking at and saw

them for the first time. I saw the woman first.

There was blood everywhere, and her face had been

shot. Then I saw the little girl in the backseat slumped

over, holding a doll. There was blood all over her, too.

I saw the gunshots through the car. I looked back at the

woman, but avoided looking at her face. I saw a bump

under her dress. She was pregnant.

I don’t remember much else after that. I know I went

back to camp and basically fell apart. They took me

off duty for a couple of days, but eventually they sent

me back to the Forward Operating Base because I was

such a mess.

After reading the account, Tom quickly placed it in

his binder of materials and closed the binder as if to

indicate that he was ready to move onto something else.

The therapist asked Tom what he was feeling, and he

indicated that he was feeling “nothing.” The therapist

followed up, saying, “Nothing at all?” Tom reluctantly

admitted that he was feeling anxious. The therapist

then asked him to read the account again, but this time

to slow down his reading rate, and allow himself to

experience the emotions he had felt at the time of the

event.

After reading the account for the second time, the

therapist sought to flush out details of the event that

Tom had “glossed over” and to focus on what appeared

to be the most difficult aspects of the situation.

THERAPIST: What part of what you just read to me is

the most difficult?

T

OM: It is all difficult. The whole thing is horrible.

T

HERAPIST: What is the worst of it, though?

TOM: I guess the worst of it is seeing that small girl in

the backseat of the car.

T

HERAPIST: What did she look like when you saw her?

(Tom describes his memory of the girl when he arrived

at the car.)

T

HERAPIST: What are you feeling right now?

T

OM: I feel sick to my stomach. I feel like I did at the

time—that I want to throw up. I am also disgusted

and sad. I killed an innocent child. There are so

many things I could have done differently not to have

taken her life.

(The therapist is aware of the assimilation process in

Tom’s use of hindsight bias. She stores that information

away for future reference because she wants to make

sure that Tom is feeling strongly as many of his natural

emotions as possible about the traumatic event.)

T

HERAPIST: Continue to feel those feelings. Don’t run

away from them. Anything else that you’re feeling?

T

OM: I feel mad at myself and guilty.

T

HERAPIST: Were you feeling mad at yourself and

guilty at the time?

T

OM: No. I was horrified.

T

HERAPIST: OK, let’s stay with that feeling.

T

OM: (Pauses.) I don’t want to feel this anymore.

T

HERAPIST: I know you don’t want to feel this anymore.

You’re doing a great job of not avoiding your feelings

here. In order to not feel like this for a long time,

you need to feel these absolutely natural feelings. Let

them run their course. They’ll decrease if you stay

with them.

After a period in which Tom experienced his feel-

ings related to the situation and allowed them to dis-

sipate, a discussion ensued regarding how hurtful it

was to Tom to hear other people’s reaction to the war.

He expressed specific frustration with the presidential

administration and its policy on the war. The therapist

gently redirected Tom’s more philosophical discussion

of international policy to the effects of the trauma on

him. Tom then told a story of how he had shared his

traumatic experience with a high school friend. He felt

that this person had a negative reaction to him as a result

of sharing the story. Tom felt judged and unsupported

by this friend. Since this experience with his friend,

Tom had refrained from telling others about his combat

experience. Using Socratic questioning, the therapist

asked Tom if there might be any reason, outside of his

actions, that someone might have a negative reaction

to hearing about the shooting. Through this exchange,

Tom was able to recognize that when others hear about

traumatic events, they also are trying to make sense of

these experiences in light of their existing belief sys-

tems. In other words, others around him might fall prey

to the “just world” belief that bad things only happen

to bad people. They also might not take into account

the entire context in which Tom shot the passengers in

the car. This recognition resulted in Tom feeling less

angry at his friend for this perceived judgment. He was

also somewhat willing to admit that his interpretation

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

89

of his friend’s reaction might have been skewed by his

own judgment of himself. In fact, later in the therapy,

when Tom was able to ask his friend directly about the

perceived reaction, the friend indicated that it had been

hard for him to hear, but that he had not been judging

Tom at all. In actuality, he was thinking about the ter-

rible predicament Tom had endured at the time.

The therapist asked Tom what stuck points he had

identified in writing and reading his account. The fol-

lowing dialogue then occurred:

T

OM: I’m not sure what the stuck points are, but from

what you’ve been asking me, I guess you question

whether or not I murdered this family.

T

HERAPIST: That’s true. I think it is worthwhile for

us to discuss the differences between blame and

responsibility. Let’s start with responsibility. From

your account, it sounds like you were responsible for

shooting the family. It sounds like other people may

have been responsible, too, given that you were not

the only person who shot at them.

(The therapist stores this fact in her mind to challenge

Tom later about the appropriateness of his actions.

This also provides a good opportunity to reinforce Tom

for performing well in a stressful situation.)

The bottom line is that responsibility is about your

behavior causing a certain outcome. Blame has to do

with your intentionality to cause harm. It has to do

with your motivations at the time. In this case, did

you go into the situation with the motivation and in-

tention to kill a family?

T

OM: No, but the outcome was that they were murdered.

T

HERAPIST: Some died. From what you’ve shared, if

we put ourselves back into the situation at the time,

it was not at all your intention for them to die. They

were coming down the road too fast, not responding

to the very clear efforts to warn them to stop. Your

own and others’ intentions were to get them to stop

at the checkpoint. Your intention at the time did not

seem to be to kill them. In fact, wasn’t your intention

quite the opposite?

T

OM: Yes. (Begins to cry.)

T

HERAPIST: (Pauses until Tom’s crying subsides some-

what.) It doesn’t seem that your intention was to kill

them at all. Thus, the word “blame” is not appro-

priate. Murder or considering yourself a murderer

does not seem accurate in this situation. The reason

I’ve questioned the term “murder” or “murderer” all

along was because it doesn’t seem like your intention

was to have to shoot them.

T

OM: But why do I feel like I am to blame?

T

HERAPIST: That’s a good question. What’s your best

guess about why that is?

T

OM: (Still crying) If someone dies, someone should

take responsibility.

T

HERAPIST: Do you think it is possible to take respon-

sibility without being to blame? What would be a

better word for a situation that is your responsibility,

but that you didn’t intend to happen? If a person shot

someone but didn’t intend to do that, what would we

call that?

T

OM: An accident, I guess.

T

HERAPIST: That’s right. In fact, what would you call

shooting a person when you are trying to protect

something or someone?

T

OM: Self-defense.

T

HERAPIST: Yes, very good. Weren’t you responsible

for guarding the checkpoint?

T

OM: Yeah.

T

HERAPIST: So, if you were responsible for guard-

ing that checkpoint, and they continued through,

wouldn’t that have put the area at risk?

T

OM: Yes, but it was a family—not insurgents.

T

HERAPIST: How did you know that at the time?

T

OM: There was woman and child in the car.

THERAPIST: But, did you know that at the time?

T

OM: No.

T

HERAPIST: So only in hindsight do you know that it

was a family that might have had no bad intention.

We actually don’t know the family’s intention, do

we? They didn’t heed the several warnings, right?

T

OM: Yes. (Pauses.) I hadn’t thought that they would

be looking to do something bad with a woman and

child in the car.

T

HERAPIST: We don’t know, and won’t ever know, bot-

tom line. However, what we do know is what you

knew at the time. What you knew at the time is that

they did not heed the warnings, that you were re-

sponsible for securing the checkpoint, and that you

took action when you needed to take action to pro-

tect the post. Thinking about those facts of what hap-

pened and what you knew at the time, how do you

feel?

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

90 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

TOM: Hmm . . . I guess I’d feel less guilty.

T

HERAPIST: You’d feel less guilty, or you feel less

guilty?

T

OM: When I think through it, I do feel less guilty.

T

HERAPIST: There may be points when you start feel-

ing guiltier again. It will be important for you to hold

onto the facts of what happened versus going to your

automatic interpretation that you’ve had for awhile

now. Is there any part of it that makes you proud?

T

OM: Proud?

T

HERAPIST: Yes. It seems like you did exactly what you

were supposed to do in a stressful situation. Didn’t

you show courage under fire?

T

OM: It’s hard for me to consider my killing them as

courageous.

T

HERAPIST: Sure. You haven’t been thinking about it

in this way for a long time, but it is something to

consider.

The therapist’s Socratic dialogue was designed to

help Tom consider the entire context in which he was

operating. She also began to plant the seed that Tom

not only did nothing wrong but he also did what he was

supposed to do to protect the checkpoint. Whenever

possible, pointing out acts of heroism or courage can be

powerful interventions with trauma survivors.

Prior to ending the session, the therapist checked

Tom’s emotional state to make sure he was calmer than

he had been during the session. She also inquired about

his reaction to the therapy session. He commented that

it had been very difficult, but that he felt better than he

expected in going into the “nitty-gritty” of what hap-

pened. He also noted that there were things he had not

considered about the event that were “food for thought.”

The therapist praised Tom for doing a great job on the

writing assignment and reinforced the importance of

not quitting now. She commented that he had complet-

ed one of the hardest steps of the therapy, which would

help him recover.

The therapist took the first account of the trauma and

gave Tom his next practice assignment: to write the en-

tire account again. The therapist asked Tom to add any

details he might have left out of the first account and

to provide even more sensory details. She also asked

him to record any thoughts and feelings he was hav-

ing in the here-and-now in parentheses, along with his

thoughts and feelings at the time of the event.

Session 5

Tom arrived at Session 5 looking brighter and making

more eye contact with the therapist. He indicated that

he had written the account again, right after the previ-

ous session. He commented that the writing was hard,

but not as hard as the first time. The therapist used this

as an opportunity to reinforce how natural emotions

resolve naturally as they are allowed expression. Tom

noted that he had talked with his wife more this week,

avoiding her less. Their increased communication al-

lowed Tom’s wife to express her concerns about Tom’s

well-being. She shared that he seemed disinterested

in her and in their unborn child. Tom had previously

told his wife about the incident, but he had not shared

the specific detail that the woman in the vehicle was

pregnant. Tom perceived his wife as having a very good

reaction to his disclosure about the pregnant woman.

He noted that she asked him questions, and that her

comments indicated that she did not blame him for his

actions. For example, she asked, “How could you have

known at the time that it was a family?” She also re-

portedly said, “It’s hard to know with terrorism if they

were actually just a family traveling.” Tom laughed

when he reported that their conversation sounded like

his last psychotherapy session.

The therapist asked Tom to read his second account

out loud, with as many emotions as possible. Tom had

written more about the event, and the therapist noted

that he had included more information about what he

and the other guards had done to warn the passengers

in the car to slow down for the checkpoint. Tom read

the second account more slowly and was not as tense as

he had been the first time he read aloud. Tom’s second

account included much more detail and focused more

on the vehicle and its occupants after he had fired upon

them.

THERAPIST: I notice that you wrote more about the car

and the family. What are you feeling about that right

now?

T

OM: I feel sad.

T

HERAPIST: Do you feel as sad as you felt the first time

you wrote about it?

T

OM: I think I may feel sadder about it now.

T

HERAPIST: Hmm . . . Why do you think that might be?

T

OM: I think it’s like what I wrote in the parenthesis

about what I’m thinking now. Now, instead of feeling

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

91

so much guilt that I shot them, I think it’s sad that

they didn’t heed the warnings.

T

HERAPIST: You mentioned that you’re feeling less

guilt now. Why is that?

T

OM: I’m beginning to realize that I was not the only

one there that was trying to stop them. Several of us

were trying to get them to stop. There is still some

guilt that I was the one who shot them.

T

HERAPIST: If one of the other guards had shot them,

would you blame him or her for the shooting? Would

you expect him or her to feel guilty for their behav-

ior?

T

OM: (Laughs.) I started thinking about that this week.

It made me wonder if it was really me who even shot

them. As I was writing and thinking about it more,

I realized that there is a possibility that another of

the guards may have been shooting at the same time.

T

HERAPIST: What would it mean if he or she was shoot-

ing at the same time?

T

OM: If he was shooting at the same time, it means that

he thought that shooting at them might be the right

thing to do in that situation.

T

HERAPIST: Might have been the right thing to do?

TOM: (smiling) Yeah, I still have questions that we

might have been able to do something else.

T

HERAPIST: It seems like you’re still trying to “undo”

what happened. I’m curious, what else could you

have done?

T

OM: Not have shot at them.

THERAPIST: Then what would have happened?

T

OM: They might have stopped. (Pauses.) Or I guess

they could have gone through the checkpoint and

hurt other people past the checkpoint. I guess they

could have also been equipped with a car bomb that

could have hurt many other people. That seems hard

to believe, though, because of the woman and child

in the car.

T

HERAPIST: It is impossible for us to know their inten-

tions, as we discussed before. The bottom line is that

you’ve tended to assume that doing something dif-

ferent, or doing nothing, would have led to a better

outcome.

T

OM: That is true. I still feel sad.

T

HERAPIST: Sure you do—that’s natural. I take it as a

good sign that you feel sad. Sadness seems like a very

natural and appropriate reaction to what happened—

much more consistent with what happened than the

guilt and self-blame that you’ve been experiencing.

Tom and the therapist discussed how the goal of the

therapy was not to forget what had happened, but to

have the memory without all of the anxiety, guilt, and

other negative emotions attached to it. Tom indicated

that he was becoming less afraid and more able to tol-

erate his feelings, even when they were intense. Tom

acknowledged that reading his account, talking about

his trauma, and coming to psychotherapy sessions were

becoming easier and that his negative feelings were be-

ginning to diminish.

After discussing Tom’s reactions to his memories,

with a focus on how he had attempted to assimilate the

memory into his existing beliefs, the therapist began

to discuss areas of overaccommodation. One area of

overaccommodation was Tom’s beliefs about the U.S.

military. He had entered the service with a very posi-

tive view of the military. Tom had a family history of

military service and believed in service to country and

the “rightfulness” of the military.

Subsequent to his traumatic event and military ser-

vice in Iraq, he developed a negative view of the mili-

tary that had extended to the Federal government in

general. The therapist used this content to introduce the

first series of tools to help challenge Tom’s stuck points.

She also emphasized how he would gradually be taking

over as his own therapist, capable of challenging his

own patterns of thinking that kept him “stuck.”

T

HERAPIST: It seems that you have some very strong

beliefs about the military and the U.S. government

since your service. I’d like to use those beliefs to

introduce some new material that will be helpful

to you in starting to challenge stuck points on your

own. You’ve done an outstanding job of considering

the way that you think and feel about things. You’ve

been very open to considering alternative interpreta-

tions of things. Starting in this session, I’m going to

help you to become your own therapist and to attack

your own stuck points directly.

T

OM: OK.

T

HERAPIST: Today we will cover the first set of skills.

We’re going to be building your skills over the next

few sessions. The first tool is a sheet called the Chal-

lenging Questions Sheet. Our first step is to identify

a single belief you have that may be a stuck point.

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

92 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

As I mentioned before, I’d like us to use your beliefs

about the Federal government now. So, if you were

to boil down what you believe about the Federal gov-

ernment or the military, what is it?

T

OM: I don’t know. I’m not sure. I guess I’d say that the

U.S.

military is extremely corrupt.

T

HERAPIST: Good. That is very clear and to the point.

So let’s go over these questions and answer them as

they relate to this belief. The first question you ask

yourself is, “What’s the evidence for and against this

idea?”

T

OM: The evidence for this is Abu Ghraib. Can you be-

lieve that they would do that? I would have also put

my own shooting under the “for” list, but I’m begin-

ning to question that.

T

HERAPIST: What other evidence is there of corrup-

tion?

T

OM: Oh, and these defense contractors . . . what a

scam! That leads me to the current administration

and its vested interests in going to war to make

money on defense contracting. And, oh, of course,

to make money on the oil coming out of these coun-

tries!

T

HERAPIST: OK. Sounds like you have some “for” evi-

dence. What about the “against” evidence?

T

OM: Well, some of my fellow soldiers were very good.

They were very committed in their service and to

the mission. I also had mostly good leaders, although

some of them were real pigs. Some were really

power-hungry a—holes, frankly.

T

HERAPIST: So, it sounds like you have some pros and

cons that support your belief that the U.S. military is

completely corrupt. In the process of changing, it is

not uncommon to have thoughts on both sides. That

is great news! It means that you are considering dif-

ferent alternatives, and are not “stuck” on one way of

seeing things. Let’s take the next one. . . .

The therapist spent the balance of the session going

over the list of questions to make sure that Tom un-

derstood them. Although most of the questions focused

on the issue of corruption in the military, other issues

were also brought in to illustrate the meaning of the

questions. For example, the therapist introduced the

probability questions with the example from Tom’s life

in which he believed that he was going to be shot by

an insurgent sniper while back home. These questions

are best illustrated with regard to issues of safety. The

therapist pointed out that perhaps not all of the ques-

tions applied to the belief on which Tom was working.

The question “Are you thinking in all-or-none terms?”

seemed to resonate with Tom the most because it ap-

plied to his belief about the military. He commented

that he was applying a few examples of what seemed to

be corruption to the entire military. Tom also indicated

that his description of the military as “extremely” cor-

rupt was consistent with the question “Are you using

words or phrases that are extreme or exaggerated?” In-

dicative of his grasp of the worksheet, Tom also noticed

that the question “Are you taking selected examples out

of context?” applied to his prior view of his behavior as

a murder in the traumatic event.

For his practice assignment prior to Session 6, Tom

agreed to complete one Challenging Questions Sheet

each day. He and the therapist brainstormed about po-

tential stuck points prior to the end of the session to

facilitate practice assignment completion. These stuck

points included “I don’t deserve to have a family,” “I

murdered an innocent family,” and “I am weak because

I have PTSD.”

Session 6

Tom completed Challenging Questions Sheets about all

of the stuck points he and the therapist had generated.

The therapist reviewed these worksheets to determine

whether Tom had used the questions as designed. She

asked Tom which of the worksheets he had found least

helpful. He responded that he had had the most diffi-

culty completing the sheet about deserving to have a

family. The therapist then reviewed this sheet in detail

with Tom (see Figure 2.2).

THERAPIST: So, I notice that in your answer about the

evidence for and against this idea about deserving a

family, you included as evidence that you took some

other man’s family. I’m glad to see that you didn’t in-

clude the word “murder”—that’s progress. But, how

is that evidence for you not deserving a family?

T

OM: It is evidence because I feel like I took someone

else’s; therefore, I don’t deserve one for myself. It

seems fair.

T

HERAPIST: Remind me to make sure and look what

you put for item 9 about confusing feelings and facts.

For now, though, help me understand the math of

why you don’t deserve your family, and your happi-

ness about your family, because of what happened?

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

93

Challenging Questions Sheet

Below is a list of questions to be used in helping you challenge your maladaptive or problematic beliefs.

Not all questions will be appropriate for the belief you choose to challenge. Answer as many questions

as you can for the belief you have chosen to challenge below.

Belief: I don’t deserve to have a family.

1. What is the evidence for and against this idea?

FOR: I took some other man’s family.

AGAINST: I didn’t want to have to shoot anyone. An “eye for an eye” does not apply here.

2. Is your belief a habit or based on facts?

It is a habit for me to think this way. The facts are that I didn’t do something wrong to deserve to be

punished in this way.

3. Are your interpretations of the situation too far removed from reality to be accurate?

My interpretation of the original situation has been fairly unrealistic, which is where I get this belief.

4. Are you thinking in all-or-none terms?

N/A

5. Are you using words or phrases that are extreme or exaggerated? (i.e., always, forever, never, need,

should, must, can’t, and every time)

I guess maybe “deserve” could be an extreme word.

6. Are you taking the situation out of context and only focusing on one aspect of the event?

Yes, like #3, I tend to forget what all was going on at the time of my shooting.

7. Is the source of information reliable?

No, I’m not very reliable these days.

8. Are you confusing a low probability with a high probability?

N/A

9. Are your judgments based on feelings rather than facts?

I’m feeling guilty like I did something wrong when the truth is that I did what I was supposed to do.

10. Are you focused on irrelevant factors?

Maybe my deserving a family has nothing to do with someone else losing theirs?

FIGURE 2.2. Challenging Questions Sheet.

TOM: I don’t know—it just seems fair.

T

HERAPIST: Fair? That implies that you did something

bad that requires you to be punished.

T

OM: As I’ve been thinking about it more, I don’t think

I did something wrong when I really look at it, but

it still feels like I did something wrong and that I

shouldn’t have something good like a wife and child

in my life.

T

HERAPIST: Maybe we should look at your response

to item 9 now. What did you put in response to the

question “Are your judgments based on feelings

rather than facts?”

From Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition, Edited by David H. Barlow, PhD

Copyright 2014 by The Guilford Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2014 The Guilford Press. All rights reserved under International Copyright Convention.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or stored in or introduced into

any information storage or retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or

mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the written permission of The Guilford Press.

Guilford Publications

370 Seventh Ave., Ste 1200

New York, NY 10001

212-431-

9800

800-365-

7006

www.guilford.com

94 CLINICAL HANDBOOK OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

TOM: I wrote, “I’m feeling guilty, like I did something

wrong when the truth is that I did what I was sup-

posed to do.” I try to remember what we talked

about, and what my wife also has said to me about

them not responding to the warnings and my shoot-

ing them, which may have prevented something else

that was bad. I still feel bad—not as bad as I did—