virtual currency schemes

OctOBer 2012

VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES

OCTOBER 2012

In 2012 all ECB

publications

feature a motif

taken from

the €50 banknote.

© European Central Bank, 2012

Address

Kaiserstrasse 29

60311 Frankfurt am Main

Germany

Postal address

Postfach 16 03 19

60066 Frankfurt am Main

Germany

Telephone

+49 69 1344 0

Website

http://www.ecb.europa.eu

Fax

+49 69 1344 6000

All rights reserved. Reproduction for

educational and non-commercial purposes

is permitted provided that the source is

acknowledged.

ISBN: 978-92-899-0862-7 (online)

3

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5

1 INTRODUCTION 9

1.1 Preliminary remarks and motivation

9

1.2 A short historical review of money

9

1.3 Money in the virtual world

10

2 VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES 13

2.1 Denitionandcategorisation

13

2.2 Virtual currency schemes and electronic money

16

2.3 Paymentarrangementsinvirtualcurrencyschemes

17

2.4 Reasonsforimplementingvirtualcurrencyschemes

18

3 CASE STUDIES 21

3.1 The Bitcoin scheme

21

3.1.1 Basic features

21

3.1.2 Technical description of a Bitcoin transaction

23

3.1.3 Monetary aspects

24

3.1.4Securityincidentsandnegativepress

25

3.2 The Second Life scheme

28

3.2.1 Basic features

28

3.2.2 Second Life economy

28

3.2.3 Monetary aspects

29

3.2.4 Issues with Second Life

30

4 THE RELEVANCE OF VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES FOR CENTRAL BANKS 33

4.1 Risks to price stability

33

4.2 Riskstonancialstability

37

4.3 Risks to payment system stability

40

4.4 Lackofregulation

42

4.5 Reputational risk

45

5 CONCLUSION 47

ANNEX: REFERENCES AND FURTHER INFORMATION ON VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES 49

CONTENTS

5

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Virtualcommunitieshaveproliferatedinrecentyears–aphenomenontriggeredbytechnological

developments and by the increased use of the internet. In some cases, these communities have

created and circulated their own currency for exchanging the goods and services they offer,

and thereby provide a medium of exchange and a unit of account for that particular virtual

community.

This paper aims to provide some clarity on virtual currencies and tries to address the issue in a

structured approach. It is important to take into account that these currencies both resemble money

and necessarily come with their own dedicated retail payment systems; these two aspects are

covered by the term “virtual currency scheme”. Virtual currency schemes are relevant in several

areasofthenancialsystemandarethereforeofinteresttocentralbanks.This,amongotherthings,

explainstheECB’sinterestincarryingoutananalysis,especiallyinviewofitsroleasacatalystfor

paymentsystemsanditsoversightrole.

This report begins by dening and classifying virtual currency schemes based on observed

characteristics;thesemight change in future,whichcould affect the currentdenition.A virtual

currency can be dened as a type of unregulated, digital money, which is issued and usually

controlled by its developers, and used and accepted among the members of a specic virtual

community.Dependingontheirinteractionwithtraditional,“real”moneyandtherealeconomy,

virtualcurrencyschemescanbeclassiedintothreetypes:Type1,whichisusedtorefertoclosed

virtualcurrencyschemes,basicallyusedinanonlinegame;Type2virtualcurrencyschemeshave

aunidirectionalow(usuallyaninow),i.e.thereisaconversionrateforpurchasingthevirtual

currency, which can subsequently be used to buy virtual goods and services, but exceptionally

alsotobuyrealgoodsandservices;andType3virtualcurrencyschemeshavebidirectionalows,

i.e.thevirtualcurrencyinthisrespectactslikeanyotherconvertiblecurrency,withtwoexchange

rates(buyandsell),whichcansubsequentlybeusedtobuyvirtualgoodsandservices,butalsoto

purchaserealgoodsandservices.

Virtual currency schemes differ from electronic money schemes insofar as the currency being

usedastheunitofaccounthasnophysicalcounterpartwithlegaltenderstatus.Theabsenceofa

distinctlegalframeworkleadstootherimportantdifferencesaswell.Firstly,traditionalnancial

actors, including central banks, are not involved. The issuer of the currency and scheme owner

is usually a non-nancial private company. This implies that typical nancial sector regulation

andsupervisionarrangementsarenotapplicable.Secondly,thelinkbetweenvirtualcurrencyand

traditionalcurrency(i.e.currencywithalegaltenderstatus)isnotregulatedbylaw,whichmight

beproblematicorcostlywhenredeemingfunds,ifthisisevenpermitted.Lastly,thefactthatthe

currency is denominated differently (i.e. not euro, US dollar, etc.) means that complete control

ofthevirtualcurrencyisgiventoitsissuer,whogovernstheschemeandmanagesthesupplyof

money at will.

There are several business reasons behind the establishment of virtual currency schemes. They may

provideanancialincentiveforvirtualcommunityuserstocontinuetoparticipate,orcreatelock-in

effects.Moreover,schemesareabletogeneraterevenuefortheirowners,forinstanceoatrevenue.

In addition, a virtual currency scheme, by allowing the virtual community owner to control its

basicelements(e.g.thecreationofmoneyand/orhowtoallocatefunds),providesahighlevelof

exibilityregardingthebusinessmodelandbusinessstrategyforthevirtualcommunity.Finally,

specicallyforType3schemes,avirtualcurrencyschememayalsobeimplementedinorderto

compete with traditional currencies, such as the euro or the US dollar.

6

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

6

TherstcasestudyinthisreportrelatestoBitcoin,avirtualcurrencyschemebasedonapeer-to-

peernetwork.Itdoesnothaveacentralauthorityinchargeofmoneysupply,noracentralclearing

house,norarenancialinstitutionsinvolvedinthetransactions,sinceusersperformallthesetasks

themselves.Bitcoinscanbespentonbothvirtualandrealgoodsandservices.Itsexchangeratewith

respecttoothercurrenciesisdeterminedbysupplyand demand and several exchange platforms

exist. The scheme has been surrounded by some controversy, not least because of its potential to

becomeanalternativecurrencyfordrugdealingandmoneylaunderingasaresultofitshighdegree

of anonymity.

The second case study in this report is Second Life’s virtual currency scheme, in which Linden

Dollars are used. This scheme can only be used within this virtual community for the purchase

ofvirtualgoodsandservices.LindenLabmanagestheschemeandactsasissuerandtransaction

processor and ensures a stable exchange rate against the US dollar. However, the Second Life

schemehasbeensubjecttodebate,andithasbeensuggestedthatthiscurrencyismorethansimply

moneyforonlinegaming.

Thereafter, a preliminary assessment is presented of the relevance of virtual currency schemes

forcentralbanks,payingattentionmostlytoschemeswhicharemoreopenandlinkedtothereal

economy(i.e.Type3schemes).Theassessmentcoversthestabilityofprices,ofthenancialsystem

andofthepaymentsystem,lookingalsoattheregulatoryperspective.Italsoaddressesreputational

risk concerns. It can be concluded that, in the current situation, virtual currency schemes:

do not pose a risk to price stability, provided that money creation continues to stay at a low −

level;

tend to be inherently unstable, but cannot jeopardise nancial stability, owing to their −

limited connection with the real economy, their low volume traded and a lack of wide user

acceptance;

are currently not regulated and not closely supervised or overseen by any public authority, −

eventhoughparticipationintheseschemesexposesuserstocredit,liquidity,operationaland

legalrisks;

couldrepresentachallengeforpublicauthorities,giventhelegaluncertaintysurroundingthese −

schemes, as they can be used by criminals, fraudsters and money launderers to perform their

illegalactivities;

could have a negative impact on the reputation of central banks, assuming the use of such −

systemsgrowsconsiderablyandintheeventthatanincidentattractspresscoverage,sincethe

publicmayperceivetheincidentasbeingcaused,inpart,byacentralbanknotdoingitsjob

properly;

do indeed fall within central banks’ responsibility as a result of characteristics shared with −

paymentsystems,whichgiverisetotheneedforatleastanexaminationofdevelopmentsand

the provision of an initial assessment.

This report is a rst attempt to provide the basis for a discussion on virtual currency schemes.

Althoughtheseschemescanhavepositiveaspectsintermsofnancialinnovationandtheprovision

7

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

of additional payment alternatives to consumers, it is clear that they also entail risks. Owing to

the small size of virtual currency schemes, these risks do not affect anyone other than users of

theschemes.Thisassessmentcouldchangeifusageincreasessignicantly,forexampleifitwere

boosted by innovations which are currently being developed or offered. As a consequence, it is

recommendedthatdevelopmentsareregularlyexaminedinordertoreassesstherisks.

9

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 PRELIMINARY REMARKS AND MOTIVATION

This report seeks to provide clarity on the topic of virtual currencies and tries to address the issue in

astructuredapproach.Suchanapproachhasbeenabsent,atleasttosomeextent,fromtheexisting

literature. Moreover, there have previously been no references to this topic in the publications of

centralbanks,internationalorganisationsorpublicauthorities.Asaconsequence,thisreportlargely

reliesoninformationanddatagatheredfrommaterialpublishedontheinternet(seetheAnnexfor

referencesandfurtherreading),whosereliability,however,cannotbefullyguaranteed.Thisplaces

serious limitations on the present study.

Virtual currencies resemble money and necessarily come with their own dedicated retail payment

systems; these two aspects are covered by the term “virtual currency scheme”. Virtual currency

schemesarerelevantinseveralareasofthenancialsystemandarethereforeofinteresttocentral

banks.Virtualcurrencyschemeshavebeensubjecttoincreasedpresscoverage,evenbeingfeatured

in respectable media publications. The ECB has been contacted a number of times in recent months

by academics, journalists and concerned citizens, who want to know its view or want to warn the

institution about potential problems with virtual currency schemes. In this context, it was considered

advisabletostriveforacommonunderstandingand,thereafter,toformulateacoordinatedresponse.

ThisexplainstheECB’sinterestincarryingoutamoredetailedanalysis,especiallyinviewofits

roleasacatalystforpaymentsystemsanditsoversightrole.Thepresentreportistheresultofthis

analysis.Itisarstattempttoprovidethebasisforadiscussiononvirtualcurrencyschemes.

This report is structured into four parts. After a brief review of the history of money in this chapter,

Chapter 2 denes and classies virtual currency schemes. It also shows how their payment

arrangementswork andaddresses the various business reasonsfor implementingthese schemes.

Chapter 3 focuses on two prominent virtual currency schemes, namely Bitcoin and Second Life’s

Linden Dollars, and describes their basic features, technical elements and monetary aspects.

It also addresses the latest issues and security incidents in which these schemes have been involved.

Chapter4offersanassessmentofhowcentralbankscouldbeaffectedbytheseschemes,taking

into account different aspects, i.e. price stability, nancial stability, the smooth operation of

paymentsystems,theregulatoryperspectiveandreputationalrisk.Thereportnishesbyoffering

conclusions and proposals for future action.

1.2 A SHORT HISTORICAL REVIEW OF MONEY

Itisdifculttoestablishthepreciseoriginsofmonetarysocieties.Itseemsthatpaymentsusing

someformofmoneywerebeingmadeasearlyas2200BC.Nevertheless,theformatofmoneyhas

changedconsiderablysincethen.Earlymoneywasusuallycommoditymoney,thatis,anobject

whichhadintrinsicvalue(e.g.cattle,seeds,etc.,andlater,goldandsilver,forinstance).

Around the eighteenthcentury, “commodity-backed”money startedto beused, whichconsisted

of items representing the underlying commodity (e.g. gold certicates). These pieces of paper

werenotintrinsicallyvaluable,buttheycouldbeexchangedforaxedquantityoftheunderlying

commodity.Themainadvantagesofthissystemweretheportabilityofthemoneyandthatlarger

amounts of money could be transferred.

Modern economies are typically based on “at” money, which is similar to commodity-backed

moneyinitsappearance,butradicallydifferentinconcept,asitcannolongerberedeemedfora

commodity.Fiat money is any legaltender designated andissued bya central authority.People

10

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

1010

arewillingtoacceptitinexchangeforgoodsandservicessimplybecausetheytrustthiscentral

authority.Trustisthereforeacrucialelementofanyatmoneysystem.

Regardlessoftheformofmoney,itistraditionallyassociatedwiththreedifferentfunctions:

Medium of exchange• : money is used as an intermediary in trade to avoid the inconveniences

of a barter system, i.e. the need for a coincidence of wants between the two parties involved in

the transaction.

Unit of account• : money acts as a standard numerical unit for the measurement of value and

costsofgoods,services,assetsandliabilities.

Store of value• : money can be saved and retrieved in the future.

Money is a social institution: a tool created and marked by society’s evolution, which has exhibited

agreatcapacitytoevolveandadapttothecharacterofthetimes.Itisnotsurprisingthatmoneyhas

beenaffectedbyrecenttechnologicaldevelopmentsandespeciallybythe widespread use of the

internet.

1.3 MONEY IN THE VIRTUAL WORLD

Sinceitsestablishmentinthe1980sandfollowingthecreationoftheWorldWideWebinthemid-

1990s,accesstoanduseoftheinternethasgrowndramatically.AccordingtoInternetWorldStats,

1

the number of internet users in the world was 361 million at the end of 2000, whereas by the end

http://www.internetworldstats.co1 m

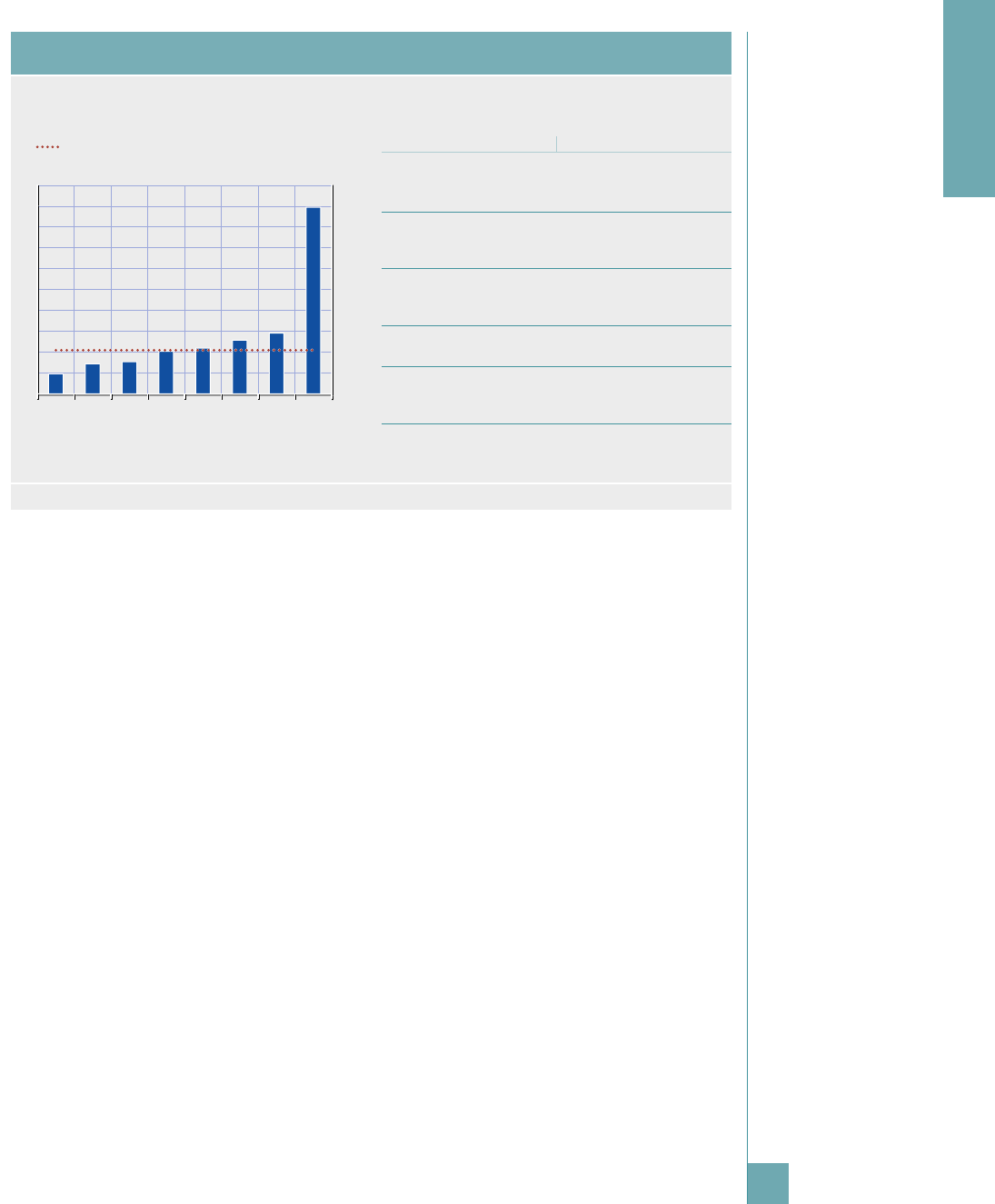

Chart 1 Internet penetration and growth by region (December 2011)

(percentage)

Internet penetration (% population) Internet penetration growth (2000-2011)

1 Africa

2 Asia

3 Europe

4 Middle East

5 North America

6 Latin America/Caribbean

7 Oceania/Australia

8 World total

21 3 4 65 7 8

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

3,200

2,800

2,400

2,000

1,600

1,200

800

400

0

21 3 4 5 6 7 8

1 Africa

2 Asia

3 Europe

4 Middle East

5 North America

6 Latin America/Caribbean

7 Oceania/Australia

8 World total

Source:InternetWorldStats.

11

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

11

I INTRODUCTION

11

of 2011 this gure had reached 2,267 million,

orapproximately33%oftheglobalpopulation.

Theimpacthasbeensosignicantthatitcould

reasonablybeconsideredastructuralchangein

socialbehaviour,affectingthewaypeoplelive,

interactwitheachother,gatherinformationand,

of course, the way they pay.

In connection with the high penetration of the

internet, there has also been a proliferation of

virtual communities in recent years. A virtual

community is to be understood as a place within

cyberspacewhereindividualsinteract and followmutualinterestsor goals. Social networkingis

probablythemostomnipresenttypeofvirtualcommunity(e.g.Facebook,MySpace,Twitter),but

thereareotherprominentcommunities,suchasthosethatshareknowledge(e.g.Wikipedia),those

thatcreateavirtualworld(e.g.SecondLife)orthosethataimtocreateanonlineenvironmentfor

gambling(e.g.OnlineVegasCasino).

Insomecases,thesevirtualcommunitieshavecreatedandcirculatedtheirowndigitalcurrencyfor

exchanging the goods and services they offer, thereby creating a new form of digital money

(see Table 1). Theexistence of competing currencies isnot new, as local, unregulated currency

communitiesexistedlongbeforethedigitalage.

2

These schemes can have positive aspects if they

contribute to nancial innovation and provide additional payment alternatives to consumers.

However,itisclearthattheycanalsoposerisksfortheirusers,especiallyinviewofthecurrent

lackofregulation.

In essence, virtual currencies act as a medium of exchange and as a unit of account within a

particularvirtualcommunity.Thequestionthenarisesastowhethertheyalsofullthe“storeof

value”functionintermsofbeingreliableandsafe,orwhethertheyposearisknotonlyfortheir

users but also the wider economy.

See 2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Local_currency

Table 1 A money matrix

Legal

status

Unregulated

– Certain types of

local currencies

– Virtual currency

Regulated

– Banknotes and

coins

– E-money

– Commercial bank

money (deposits)

Physical Digital

Money format

Source: ECB.

13

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

2 VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES

2.1 DEFINITION AND CATEGORISATION

Againstthe backgroundprovided inthe previouschapter andbased onobserved characteristics,

itispossibletoprovidethefollowingdenitionofvirtualcurrency:“avirtualcurrencyisatype

ofunregulated,digitalmoney,whichisissuedandusuallycontrolledbyitsdevelopers,andused

andacceptedamongthemembersofaspecicvirtualcommunity”.Thisdenitionmayneedtobe

adaptedinfutureiffundamentalcharacteristicschange.

There are typically two ways to obtain virtual currencies. In many virtual currency schemes, the

fastest way is to purchase it using “real” money at a conversion rate that has been previously

established;

1

the virtual currency itself usually has no commodity-backed value.

2

Secondly, users

can often increase their stock by engagingin specic activities, for instance by responding to a

promotionoradvertisementorbycompletinganonlinesurvey.

There are many different virtual currency schemes and it is not easy to classify them. One

possibility is to focus on their interactions with real money and the real economy. This occurs

throughtwo channels: a) the monetaryow via currency exchanges; andb) the realow inthe

senseofthepossibilitytopurchaserealgoodsandservices.Takingthisasabasis,threetypescan

bedistinguished:

1) Closed virtual currency schemes. These schemes have almost no link to the real economy and

aresometimescalled“in-gameonly”schemes.

3

Users usually pay a subscription fee and then

earn virtual money based on their online performance. The virtual currency can only be spent

bypurchasingvirtualgoodsandservicesofferedwithinthevirtualcommunityand,atleastin

theory, it cannot be traded outside the virtual community.

Forthetimebeing,thereseemstobenovirtualcurrencyexchangesystemfortransferringandexchangingmoneybetweenthedifferent1

virtualcommunities.Thissituationcouldchangeifinitiatives,suchas“CurrencyConnect”(http://www.currencyconnect.com/) succeed.

Theremaybeexceptions.Forinstance,e-gold(2 http://www.e-gold.com/) is a virtual currency scheme, which was founded in 1996 and

isoperatedbyGold&SilverReserveInc.tradingase-goldLtd.Thiscurrencyis100%backedbyphysicalgold(orsilver,platinumand

palladium)heldinlocationsaroundtheworld,suchasLondonorZurich.Usersopeningane-goldaccountareactuallybuyingaquantity

ofgold. Thevalue of theaccount is linkedto theprice of gold.The system,which also allowsthe transfer ofmoney toother users,

operateswithsomecompaniesactingasmarketmakers,buyingandsellingthisvirtualcurrency(i.e.theunderlyingmetal)againstother

currencies.TheUSauthoritieshaveaccusedthisschemeofviolatinganti-moneylaunderingregulations.In2008thecompany’sfounder

andtwoseniordirectorsagreedtopleadguiltytovariouschargesrelatedtomoneylaunderingandtheoperationofanunlicensedmoney

transferbusiness.In2009thecompanycontactedtheUSGovernmentinordertoreconvertitsactivity.Thedialogueculminatedinthe

development of a Value Access Plan acceptable to both the company and the Government. Once this plan is implemented, the expectation

isthatuserswillagainhaveaccesstothevalueintheiraccounts.

Strauss (2010).3

Example: World of Warcraft (WoW) Gold is a virtual currency used in this well-known

online role-playing game designed by Blizzard Entertainment. Players have different options

(with different subscription fees) for opening an account and starting to play. WoW Gold is

neededasameansofexchangeinthegame,forinstanceinorderforplayerstoequipthemselves

wellenoughtoreachhigherlevels.PlayershaveseveralopportunitiestoearnWoWGoldwithin

thegame.BuyingandsellingWoWGoldintherealworldisstrictlyforbiddenundertheterms

and conditions established by Blizzard Entertainment.

1

1 However, there seems to be a black market for buying and selling WoW Gold outside the virtual currency scheme. If Blizzard

Entertainmentdiscoversanyillegalexchange,itcansuspendorbanaplayer’saccount.

14

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

1414

2) Virtual currency schemes with unidirectional ow. The virtual currency can be purchased

directly using real currency at a specic exchange rate, but it cannot be exchanged back to

theoriginalcurrency.Theconversionconditionsareestablishedbytheschemeowner.Type2

schemesallowthecurrencytobeusedtopurchasevirtualgoodsandservices,butsomemay

alsoallowtheircurrenciestobeusedtopurchaserealgoodsandservices.

3) Virtual currency schemes with bidirectional ow. Users can buy and sell virtual money

accordingtotheexchangerateswiththeircurrency.Thevirtualcurrencyissimilartoanyother

convertible currency with regard to its interoperability with the real world. These schemes

allowforthepurchaseofbothvirtualandrealgoodsandservices.

Example 1: Facebook Credits (FB), Facebook’s virtual currency was introduced in 2009 to

allowuserstobuyvirtualgoodsinanyapplicationontheFacebookplatform.Itwaspossible

tobuythiscurrencyusingacreditcard,PayPalaccountoravarietyofotherpaymentmethods.

A purchase made using any other currency than US dollars would undergo a conversion

into US dollars using a daily exchange rate, before beingexchanged for Facebook Credits

attherateofFB1=USD0.10.UserswereabletogainadditionalFacebookCreditsthrough

special promotions, for instance if they made online purchases. The terms on the website did

not provide for a conversion back to US dollars.

1

Surprisingly, in June 2012 the company

announced that it would “update the payments product” and that it would convert all prices

and balances that were quoted in Facebook Credits into local currency amounts starting

inJuly2012.

2

Example 2: The virtual currency scheme set up by Nintendo, called Nintendo Points, can be

redeemed in Nintendo’s shops and in their games. Consumers can purchase points online by

usingacreditcardorinretailstoresbypurchasingaNintendoPointsCard.ThePointscannotbe

converted back to real money.

1 See Liu (2010).

2 Seehttp://developers.facebook.com/blog/post/2012/06/19/introducing-subscriptions-and-local-currency-pricing/

Example: Linden Dollars (L$) is the virtual currency issued in Second Life, a virtual world

whereuserscreate“avatars”,i.e.digitalcharactersthatcanbecustomised.SecondLifehas

its own economy where users can buy and sell goods and services from and to each other.

In order to do so, they need Linden Dollars, which can be purchased with US dollars and

other currenciesaccording totheexchangeratesestablishedin the currencytradingmarket.

A credit card or PayPal account is needed. Users can sell their spare Linden Dollars in return

for US dollars.

15

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

15

2 VIRTUAL CURRENCY

SCHEMES

15

Chart 2 Types of virtual currency scheme

Real economy money

Virtual money

Can be used for virtual

and real goods and

services

Type 3

Real economy money

Virtual money

Used only for virtual

goods and services

Type 1

Real economy money

Virtual money

Can be used for virtual

and real goods and

services

Type 2

Source: ECB.

Note: A subscription fee may be required for Type 1.

Box 1

FREQUENT-FLYER PROGRAMMES

Loyalty programmes in the form of vouchers, coupons and bonus points have long existed.

Airlines’points/airmilesprogrammesareoneoftheserewardsystemsimplementedtoincrease

frequentyers’loyaltytowardsthecompany.Everytimeacustomerbuysaightorpayswitha

creditcardlinkedtothefrequent-yerprogramme,theyreceiveadditionalairmilesthatcanbe

exchangedforfreeightsorforanupgradetobusinessclass.

AshighlightedbyTheEconomist(2005),theseprogrammeshavereachedoutstandingvalues,

evensurpassingthetotalamountofdollarnotesandcoinsincirculation(i.e.theM0supply).

Airlinecompaniesalsosellmilestocreditcardrms,generatingsubstantialadditionalrevenue

for airlines. In addition, these programmes form part of the airlines’ marketing and business

strategies.Byprovidingthefrequentyerwithairmilesforbuyingaightataparticulartime

or,onthecontrary,bymakingithardertospendairmiles(e.g.requestingmoreairmilesfora

freeightorrestrictingthenumberofseatsavailable),theairlinescaninuencetheircustomers’

demand.Inpractice,thismeansthattheairlinescanmanagethesupplyofairmilesaccordingto

theirownstrategy.

Based on the denition and concept of virtual currency schemes developed in this section,

frequent-yerprogrammescanbeviewedasaspecictypeofvirtualcurrencyscheme,which

exhibitsthefollowingfeatures:

Usersusuallyreceiveairmilesforbuyingaight,buttheycanalsoearntheminmanyother –

ways(e.g.bypayingwithalinkedcreditcard,byrespondingtoapromotion,etc.).Userscan

alsobuyairmileswithrealmoneyataspecicexchangerate.

16

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

1616

2.2 VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES AND ELECTRONIC MONEY

Virtualcurrency schemes canbe considered tobe a specictype of electronicmoney, basically

used for transactions in the online world. However, a clear distinction should be made between

virtual currency schemes and electronic money (see also Table 2).

According to the Electronic Money Directive (2009/110/EC), “electronic money” is monetary

value as represented by a claim on the issuer which is: stored electronically; issued on receipt of

funds of an amount not less in value than the monetary value issued; and accepted as a means of

paymentbyundertakingsotherthantheissuer.

Althoughsomeofthesecriteriaarealsometbyvirtualcurrencies,thereisoneimportantdifference.

In electronic money schemes the link between the electronic money and the traditional money

formatis preservedand has a legal foundation,as thestored funds are expressed in the sameunit

ofaccount(e.g.USdollars,euro,etc.).Invirtualcurrencyschemestheunitofaccountischanged

intoavirtualone(e.g.LindenDollars,Bitcoins).Thisisnotaminorissue,specicallyinType3

schemes.Firstly,theseschemesrelyonaspecicexchangeratethatmayuctuate,sincethevalue

of the virtual currency is usually based on its own demand and supply. Secondly, to some extent

the conversion blursthelink totraditional currency, which might beproblematic when retrieving

funds, if this is even permitted. Lastly, the fact that the currency is denominated differently

(i.e. not in euro, US dollar, etc.) and that the funds do not need to be redeemed at par value means that

completecontrolofthevirtualcurrencyislefttoitsissuer,whichisusuallyanon-nancialcompany.

Oncethemoneyisinthesystem,itcannotlegallyberedeemedintorealmoney.However,as –

is the case with other virtual currencies, there may also be a black market for air miles.

Air miles can be used to purchase real goods, i.e. ights. However, it seems that some –

schemesalsoallowairmilestobeusedwhenbuyingotherrealgoodsandservices,butthis

practiceseemstobemarginalatthisstage.

Taking all these elements into account, it is possible to classify the airlines’ frequent-yer

programmesascharacteristicoftheType2virtualcurrencyschemes.

Table 2 Differences between electronic money schemes and virtual currency schemes

Electronic money schemes Virtual currency schemes

Money format

Digital Digital

Unit of account

Traditional currency (euro, US dollars, pounds, etc.)

withlegaltenderstatus

Invented currency (Linden Dollars,

Bitcoins,etc.)withoutlegaltenderstatus

Acceptance

Byundertakingsotherthantheissuer Usuallywithinaspecicvirtualcommunity

Legal status

Regulated Unregulated

Issuer

Legallyestablishedelectronicmoneyinstitution Non-nancialprivatecompany

Supply of money

Fixed Notxed(dependsonissuer’sdecisions)

Possibility of redeeming funds

Guaranteed (and at par value) Notguaranteed

Supervision

Yes No

Type(s) of risk

Mainly operational Legal,credit,liquidityandoperational

Source: ECB.

17

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

17

2 VIRTUAL CURRENCY

SCHEMES

17

Moreover, electronic money schemes are regulated and electronic money institutions that

issue means of payment in the form of electronic money are subject to prudential supervisory

requirements. This is not the case for virtual currency schemes.

Consequently, the risks faced by each type of money are different. Electronic money is primarily

subject to the operational risk associated with potential disruptions to the system on which the

electronic money is stored. Virtual currencies are not only affected by credit, liquidity and

operationalriskwithoutanykindofunderlyinglegalframework,theseschemesarealsosubjectto

legaluncertaintyandfraudrisk,asaresultoftheirlackofregulationandpublicoversight.

The denition of virtual currency schemes used in this report excludes an entity like PayPal, the

internet-basedpaymentsystem.Althoughavirtualaccountiscreated,novirtualcurrencyisissuedin

the PayPal environment. A PayPal account is funded via credit transfer from a bank account or by a

creditcardpayment,i.e.itoperateswithinthebankingsystem.Besides,itsEuropeansubsidiaryisbased

inLuxembourgandhasbeenoperatingwithanEUbankinglicencesince2007.Asaconsequence,

PayPalissupervisedbytheCommissiondeSurveillanceduSecteurFinancierofLuxembourgandthe

electronicmoneyschemeisoverseenbytheBanquecentraleduLuxembourg.

2.3 PAYMENT ARRANGEMENTS IN VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES

Justlikeintherealeconomy,inavirtualeconomythereareawiderangeofeconomicactorswho

engageintransactionsthathavetobesettled.Thesetransactionshavetwosettlementcomponents:a)

thedeliveryof(usuallyvirtual,butpotentiallyalsoreal)goodsandservices;andb)thetransferof

funds.

A“paymentsystem”canbedenedasasetofinstruments,procedures,andrulesforthetransferof

fundsamongsystemparticipants.Itistypicallybasedonanagreementbetweentheparticipantin

thesystemandthesystemoperator,andthetransferoffundsisconductedusinganagreedtechnical

infrastructure.

4

In essence, virtual currency schemes work much like retail payment systems, except

forthefactthatnancialintermediariesarenotusuallyinvolvedinthepaymentprocess.Virtual

currency schemes demonstrate three main elements or processes of a retail payment system:

5

Apaymentinstrumentisusedasthemeansofauthorisingandsubmittingthepayment.a)

Processingandclearinginvolvesapaymentinstructionbeingexchangedbetweenthecreditorb)

and the debtor concerned.

Debits and credits are settled in the user’s account. c)

Althoughtherearedifferentmodelsthatmayleadtoimportantvariations,thefollowingspecic

featurescantypicallybeobservedforpaymentarrangementswithinvirtualcurrencyschemes:

Agents involved – :Virtualcurrenciesareheld outside the traditional banking channels.Anon-

nancialinstitutionplaysthecrucialroleandtherearenootherinstitutionsprovidingpayment

accountsorpayment services, ororganisationsthat operate payment,clearingand settlement

services. In this regard, virtual currency schemes work like traditional three-party schemes

BIS(2001),p.14,andECBGlossaryofTermsRelatedtoPayment,ClearingandSettlementSystems.4

Kokkola (ed.) (2010), p. 25.5

18

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

1818

with a scheme-owned processor. The accounts to be debited and credited are held within this

organisation,whichisthevirtualcommunityoperator.Virtualcurrencypaymentsaretherefore

handled “in house” and can be classied as a specic type of “on-us” transaction, that is,

a transfer of a claim on the virtual currency issuer.

Type of transactions: – From a conceptual perspective, payments can be classied as retail

payments, i.e. a large number of payments with small values. The payment instrument is

typically a virtual credit transfer.

Type of settlement: – Payments are usually settled on a gross basis. Each payment instruction

ispassedonandsettledindividuallyacrosstheaccountsofthepayerandthepayee,resulting

inadebitandcreditentryforeverysinglepaymentinstructionsettled.Asageneralrule,the

settlementisinrealtime,i.e.onacontinuousbasisthroughoutanentireday.

2.4 REASONS FOR IMPLEMENTING VIRTUAL CURRENCY SCHEMES

Thereareseveralreasonsforavirtualcommunitytoissueitsownvirtualcurrency.Byimplementing

avirtualcurrencyschemefocusedontheonlineworld(basicallyforvirtualgoodsandservices)

acompanycangenerateadditionalrevenue.Theuseofvirtualcurrenciescanhelpmotivateusers

bysimplifyingtransactionsandbypreventingthemfromhavingtoentertheirpersonalpayment

details every time they want to make a purchase. It can also help lock users in if, for instance,

itispossibletoearnvirtualmoneybylogginginperiodically.Ifusersareaskedtolloutasurvey

or to answer other questions in order to earn extra virtual money, users reveal their preferences,

therebyprovidingvaluableinformationforcommercialuse.Virtualcurrenciescanalsobeusedas

animportanttoolforapplicationdevelopersandadvertiserswhendesigningastrategytoreapthe

benetsofthevirtualgoodsmarket.

Atthisstage,itisverydifculttocomeupwithareliablegureforthesizeofthevirtualgoods

market.

6

On the one hand, there is no universal criterion of what the virtual goods market

encompasses.Ontheotherhand,innovationsinthiseldaregrowingandspreadingsignicantly

and,therefore, it is nearlyimpossible to gathertheinformation necessary toprovidea complete

picture of the virtual communities and virtual currency schemes that exist. Nevertheless, there are a

fewestimatescirculatingontheinternet.Theseshowthemodestmagnitudethatthismarket,which

isparticularlyconcentratedinAsiaandtheUnitedStates,mayhavereached(seeChart3).Although

mostoftheseestimatesarenotmadeonascienticbasis,theyallindicatethatthesizeofthevirtual

goodsmarketisfarfromreachingitspotentialandthatitwillgrowinthefuture.

Traditionalpayment serviceproviders donot want to get left behind either. VISA, for instance,

recently acquired PlaySpan Inc. for USD 190 million, with additional considerations for performance

milestones. PlaySpan is a privately held company, whose payments platform handles transactions

for digital goods in online games, digital media and social networks around the world.

7

Avirtualgoodorresourcecanbedenedas“anyvirtual-worldobject/servicethatincreases[…]satisfaction,desirabilityorusefulness,6

for example, website goodwill, e-books, music les, game equipments, rights to access web, or e-payment services a site provides”

(Guo,ChowandGong,2009,p.85).Therefore,anillustrationofaowersenttosomeoneelseinasocialnetworkorbetterequipmentfor

acharacterwhichisneededtoreachhigherlevelsinanonlinegamearetwoexamplesofvirtualgoodsthataresoldinvirtualcommunities.

However,inourview,thereshouldbeacleardifferentiationbetweengoodsthatareusedonlyinthevirtualenvironmentandthosewhich

areusedintherealworld(e.g.musiclesorelectronicbooks).

See the company’s press release (7 http://corporate.visa.com/media-center/press-releases/press1099.jsp).

19

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

19

2 VIRTUAL CURRENCY

SCHEMES

19

In September 2011, American Express paid USD 30 million for Sometrics, a four-year-old company

thathelps video game makersestablish virtual currenciesandvirtual currency commercewithin

theirgames.

8

Apparently, the company plans to build a virtual currency platform in other industries,

takingadvantageofitsmerchantrelationships.

Anadditionalreasonforimplementingavirtualcurrencyschemeisthepossibility,inType2and

3schemes,toobtainnewrevenuefromtheoatthatresultsfromthetimedifferencebetweenthe

moment at which money is transferred into the system and the moment at which it is taken out

fromthesystemagain(either–inType3only–viaacurrencyexchangeor–forbothtypes–

followingthepurchaseofgoodsandservicesfromthirdparties).Inaddition,schemeownersmay

alsomakeabreakageprotfrommoneywhichisnotspentorexchangedback afteritsowners

stopbeingactiveusers.

Ingeneral, the motivationfor setting upType 3 schemesmay differ fromthe incentives forthe

otherschemes;ofparticularinterestaretheschemesdesignedtocompeteagainstrealcurrencies

asamediumofexchange.Forthetimebeing,themostprominentcaseisBitcoinwhich,according

to its creators and supporters, should overcome the limitations of traditional currencies that result

fromthemonopolisticsupplyandmanagementbycentralbanks.

See Button (2011).8

Chart 3 Estimates for the size of the virtual goods market

(USD billions)

GDP in selected countries, 2011

estimated size of the US market for virtual goods

in 2011

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1 Guinea-Bissau

2 Belize

3 Liberia

4 San Marino

5 Central African Republic

6 Guyana

7 Sierra Leone

8 Malta

Source Estimated size

C.Hudson(2008)

SoftTech VC and Bionic

Panda Games

USD 200 million in 2008

C. C. Miller and B. Stone (2009)

New York Times

USD 1 billion in the United

States in 2008;

USD 5 billion worldwide

B. Parr (2009)

Mashable

USD 1 billion in the US market;

USD 7 billion in the Asian

market

A. Shukla (2008)

Offerpal Media

USD 2 billion in the United

States in 2008

J.SmithandC.Hudson(2010)

Inside Network

USD 1.6 billion in the United

States in 2010; will reach

USD 2.1 billion overall in 2011

M. Shiels (2009)

BBC News

USD 5 billion in the United

Statesinveyears;inAsiathis

gurehasalreadybeenreached

Sources:IMFWorldEconomicOutlookdatabaseandSmithandHudson(2010)estimate.

21

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

ThischapterfocusesontwoprominentType3virtualcurrencyschemes;therstisBitcoinandthe

second is the scheme established by Linden Lab for Second Life, namely Linden Dollars.

3.1 THE BITCOIN SCHEME

3.1.1 BASIC FEATURES

Bitcoin is probably the most successful – and probably most controversial – virtual currency scheme

todate.DesignedandimplementedbytheJapaneseprogrammerSatoshiNakamotoin2009,

1

the

schemeisbasedonapeer-to-peernetworksimilartoBitTorrent,thefamousprotocolforsharing

les,suchaslms,gamesandmusic,overtheinternet.Itoperatesatagloballevelandcanbeused

asacurrencyforallkindsoftransactions(forbothvirtualandrealgoodsandservices),thereby

competingwithofcialcurrenciesliketheeuroorUSdollar.Theschememaintainsadatabasethat

lists product and service providers which currently accept Bitcoins.

2

These products and services

rangefrominternetservicesandonlineproductstomaterialgoods(e.g.clothingandaccessories,

electronics,books,etc.)andprofessionalortravel/tourismservices.Bitcoinsaredivisibletoeight

decimal places enabling their use in any kind of transaction, regardless of the value.

Although

Bitcoin is a virtual currency scheme, it has certain innovations that make its use more similar to

conventional money (see Box 3 in Chapter 4).

Bitcoinsarenotpeggedtoanyreal-worldcurrency.Theexchangerateisdeterminedbysupplyand

demandinthemarket.ThereareseveralexchangeplatformsforbuyingBitcoinsthatoperateinreal

time.

3

Mt.GoxisthemostwidelyusedcurrencyexchangeplatformandallowsuserstotradeUS

dollars for Bitcoins and vice versa. As previously stated, Bitcoin is based on a decentralised, peer-

to-peer(P2P)network,i.e.itdoesnothaveacentralclearinghouse,norarethereanynancialor

other institutions involved in the transactions. Bitcoin users perform these tasks themselves. In the

samevein,thereisnocentralauthorityinchargeofthemoneysupply.Aswillbeexplainedlater,

themoneysupplyisdeterminedbyaspecictypeof“mining”activity.Itdependsontheamount

of resources (electricity and CPU time) that “miners” devote to solving specic mathematical

problems.

InordertostartusingBitcoins,usersneedtodownloadthefreeandopen-sourcesoftware.Purchased

Bitcoinsarethereafterstoredinadigitalwalletontheuser’scomputer.Consequently,usersface

theriskoflosingtheirmoneyiftheydon’timplementadequateantivirusandback-upmeasures.

Users have several incentives to use Bitcoins. Firstly, transactions are anonymous, as accounts are

notregisteredandBitcoinsaresentdirectlyfromonecomputertoanother.

4

Also, users have the

possibilityofgeneratingmultipleBitcoinaddressestodifferentiateorisolatetransactions.Secondly,

transactions are carried out faster and more cheaply than with traditional means of payment.

Transactionsfees,ifany,areverylowandnobankaccountfeeischarged.

However,thisisnothis/herrealname.SeetheentryontheBitcoinwiki(1 https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Satoshi_Nakamoto). The content of this

chapter partially relies on the information provided by Bitcoin (http://www.bitcoin.org/) and the Bitcoin community (https://en.bitcoin.it/

wiki/FAQ).TheoriginalpaperbyNakamoto(2009)isalsoused.

See 2 https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Trade

TheseareMt.Gox,TradeHill(closeddownin2012),Bitomat,Britcoin,Intersango,ExchangeBitcoin.com,CampBX,Bitcoin7,VirtEx,3

VirWox or WM-Center. For smaller amounts, the options are limited due to bank transfer fees, conversion fees and restrictions on

transactionsize.OptionsincludeBitcoinMarket,BitMarket.eu,Bitcoiny.cz,Bit/BTCChina,Bitfunnel,#bitcoin-otc,BitcoinExchange

Services, Lilion Transfer, Nanaimo Gold, Bitcoin Morpheus, Bitcoin Argentina, Bitcoin.com.es, Bahtcoin, Bitcoin Brasil, BitPiggy,

GetBitcoin, Bitcoin 4 Cash, Bitcoin2Cash, bitcoin.local, YouTipIt and Ubitex.

However,itseemsthatallBitcointransactionsarerecordedandcan,undercertaincircumstances(e.g.lawenforcement),betraced.4

3 CASE STUDIES

22

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

2222

Box 2

ECONOMIC FOUNDATIONS OF BITCOIN

The theoretical roots of Bitcoin can be found in the Austrian school of economics and its

criticism of the current at money system and interventions undertaken by governments and

otheragencies,which,intheirview,resultinexacerbatedbusinesscyclesandmassiveination.

One of the topics upon which the Austrian School of economics, led by Eugen von

Böhm-Bawerk, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich A. Hayek, has focused is business cycles.

1

In short, according to the Austrian theory, business cycles are the inevitable consequence of

monetary interventions in the market, whereby an excessive expansion of bank credit causes an

increaseinthesupplyofmoneythroughthemoneycreationprocessinafractional-reservebanking

system,whichinturn leads toarticiallylowinterestrates.

2

In this situation, the entrepreneurs,

guidedbydistortedinterestratesignals,embarkonoverlyambitiousinvestmentprojectsthatdo

not match consumers’ preferences at thattime relating to intertemporal consumption (i.e. their

decisionsregardingnear-termandfutureconsumption).Soonerorlater,thiswidespreadimbalance

cannolongerbesustainedandleadstoarecession,duringwhichrmsneedtoliquidateanyfailed

investment projects and readapt (restructure) their production structures in line with consumers’

intertemporal preferences. As a result, many Austrian School economists call for this process to be

abandonedbyabolishingthefractional-reservebankingsystemandreturningtomoneybasedon

thegoldstandard,whichcannotbeeasilymanipulatedbyanyauthority.

Another related area in which Austrian economists have been very active is monetary theory.

OneoftheforemostnamesinthiseldisFriedrichA.Hayek.Hewrotesomeveryinuential

publications, such as Denationalisation of Money(1976),inwhichhepositsthatgovernments

should not have a monopoly over the issuance of money. He instead suggests that private

banksshouldbeallowedtoissuenon-interest-bearingcerticatesbasedontheirownregistered

trademarks. These certicates (i.e. currencies) should be open to competition and would be

tradedatvariableexchangerates.Anycurrenciesabletoguaranteeastablepurchasingpower

would eliminate other less stable currencies from the market.

3

The result of this process of

competitionandprotmaximisationwouldbeahighlyefcientmonetarysystemwhereonly

stable currencies would coexist.

ThefollowingideasaregenerallysharedbyBitcoinanditssupporters:

TheyseeBitcoinas a goodstartingpointto end the monopolycentralbankshave in the –

issuance of money.

They strongly criticise the current fractional-reserve banking system whereby banks can –

extend their credit supply above their actual reserves and, simultaneously, depositors can

withdraw their funds in their current accounts at any time.

Theschemeisinspiredbytheformergoldstandard. –

1 A description of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory can be found, for instance, in Rothbard (2009).

2 Fractional-reservebankingisaformofbankingwherecreditinstitutionsmaintainreserves(incashandcoinorindepositsatthecentral

bank) that are only a fraction of their customers’ deposits. Funds deposited into a bank are mostly lent out, and banks keep only a fraction

(calledthereserveratio)ofthequantityofdepositsasreserves.Modernbankingsystemsarebasedonfractional-reservebanking.

3 AninterestingspeechonthisissuecanbefoundinIssing(1999).

23

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

23

3 CASE STUDIES

23

3.1.2 TECHNICAL DESCRIPTION OF A BITCOIN TRANSACTION

The technical aspects of this system are complex and not easy to understand without a sound technical

background. Therefore, a comprehensive explanation of the underlying technical mechanism of

Bitcoin lies outside the scope of this report. This section aims simply to provide a basic description

ofthefunctioningofthisvirtualcurrencyscheme.Accordingtothefounder,Nakamoto(2009),an

electroniccoincanbedenedasachainofdigitalsignatures.Eachownerofthecurrency(P

i

) has a

pairofkeys,onepublicandoneprivate.Thesekeysaresavedlocallyinaleand,consequently,a

lossordeletionofthelewouldmeanthatallBitcoinsassociatedwithitarelostaswell.

5

AsimpliedillustrationofachainoftransactionsfromonenodetoanothercanbefoundinChart4.

The virtual coin shown in the picture is the same one, but at different points in time. To initiate the

transaction, the future owner P

1

hastorstsendhispublickeytotheoriginalownerP

0

. This owner

transferstheBitcoinsbydigitallysigningahash

6

of the previous transaction and the public key of

thefutureowner.EverysingleBitcoincarriestheentirehistoryofthetransactionsithasundergone,

and any transfer from one owner to another becomes part of the code. The Bitcoin is stored in such

a way that the new owner is the only person allowed to spend it.

Allsignedtransactionsarethensenttothenetwork,whichmeansthatalltransactionsarepublic

transactions,althoughnoinformationisgivenregardingtheinvolvedparties.Thekeyissuetobe

addressed by the system is the avoidance of double spending, i.e. how to prevent a coin being

copiedorforged,especiallyconsideringthereisnointermediaryvalidatingthetransactions.The

solution implemented is based on the concept of a “time stamp”, which is an online mechanism

Userscanalsousespecicwebservicestostoretheirmoney.Theseservicesallowpeopletoaccesstheirmoneyfromeverywhere,but5

alsoentailrisksasusersareoutsourcingthemanagementoftheirmoneytoanunknownthirdparty.

Ahash,orhashvalue,isthevaluereturnedbyanalgorithmthatmapslargedatasetstosmallerdatasetsofxedlength.6

AlthoughthetheoreticalrootsoftheschemecanbefoundintheAustrianSchoolofeconomics,

Bitcoinhasraisedseriousconcernsamongsomeoftoday’sAustrianeconomists.Theircriticism

covers two general aspects:

4

a) Bitcoins have no intrinsic value like gold; they are mere bits

storedinacomputer;andb)thesystemfailstosatisfythe“MiseanRegressionTheorem”,which

explainsthatmoneybecomesacceptednotbecauseofagovernmentdecreeorsocialconvention,

butbecauseithasitsrootsinacommodityexpressingacertainpurchasingpower.

4 As described in Matonis (2011).

Chart 4 A chain of Bitcoin transactions

• P

0

signature

• Hash

0

containing all

previous

transactions

• P

1

signature

• Hash

1

containing all

previous

transactions

• P

2

signature

• Hash

2

containing all

previous

transactions

Bitcoin x

t=0

Bitcoin x

t=1

Bitcoin x

t=2

+ P

0

private key

+ P

1

public key

+ P

1

private key

+ P

2

public key

Transaction 1 Transaction 2

Source: ECB.

24

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

2424

usedtoensurethataseriesofdatahaveexistedandhavenotbeenalteredsinceaspecicpointin

time,inordertogetintothehash.Eachtimestampincludestheprevioustimestampinitshash,

formingachainofownership.Bybroadcastingthenewtransactions,thenetworkcanverifythem.

The systems that validate the transactions are called “miners” – essentially these are extremely fast

computers in the Bitcoin network which are able to perform complex mathematical calculations

that aim to verify the validity of transactions. The people who use their systems to undertake this

miningactivitydosoonavoluntarybasis,buttheyarerewardedwith50newlycreatedBitcoins

everytimetheirsystemndsasolution.

“Mining”isthereforetheprocessofvalidatingtransactionsbyusingcomputingpowertondvalid

blocks (i.e. to solve complicated mathematical problems) and is the only way to create new money

in the Bitcoin scheme.

7

AccordingtoNakamoto(2009),miningisalsoaveryreliableprocedureforthesecurityandsafety

ofthesystemasitprovidestheincentivetoacthonestly:“ifagreedyattackerisabletoassemble

moreCPUpowerthanallthehonestnodes,hewouldhavetochoosebetweenusingittodefraud

peoplebystealingbackhispayments,orbyusingittogeneratenewcoins.Heoughttonditmore

protabletoplaybytherules,suchrulesthatfavourhimwithmorenewcoinsthaneveryoneelse

combined,thantounderminethesystemandthevalidityofhisownwealth”.However,aswillbe

explainedlater,fraudstersmaystillhavenon-nancialincentivestocompromisethesystem.

3.1.3 MONETARY ASPECTS

The Bitcoin scheme is designed as a

decentralised system where no central monetary

authority is involved. Bitcoins can be bought

on different platforms. However, new money

is created and introduced into the system only

viatheabove-mentionedminingactivity,i.e.by

rewardingthe“miners”whoperformthecrucial

role of validating all transactions made, with

new Bitcoins.

Therefore, the supply of money does not depend

on the monetary policy of any virtual central

bank, but rather evolves based on interested

usersperformingaspecicactivity.According

to Bitcoin, the scheme has been technically

designedin such away that themoney supply

will develop at a predictable pace (see Chart 5).

The algorithms to be solved (i.e. the new

blocks to be discovered) in order to receive

newly created Bitcoins become more and

more complex (more computing resources are

AsstatedontheBitcoinwebsite,fromatechnicalpointofview,miningisthecalculationofahashofablockheader,whichincludes,7

amongotherthings,areferencetothepreviousblock,ahashofasetoftransactionsandanonce(a32-bit/4-byteeldwhosevalueisset

sothatthehashoftheblockwillcontainarunofzeros).Ifthehashvalueisfoundtobelessthanthecurrenttarget(whichisinversely

proportionaltothedifculty),anew block is formed andtheminergets50newlygeneratedBitcoins.If the hash is notlessthanthe

currenttarget,anewnonceistried,andanewhashiscalculated.Thisisdonemillionsoftimespersecondbyeachminer.

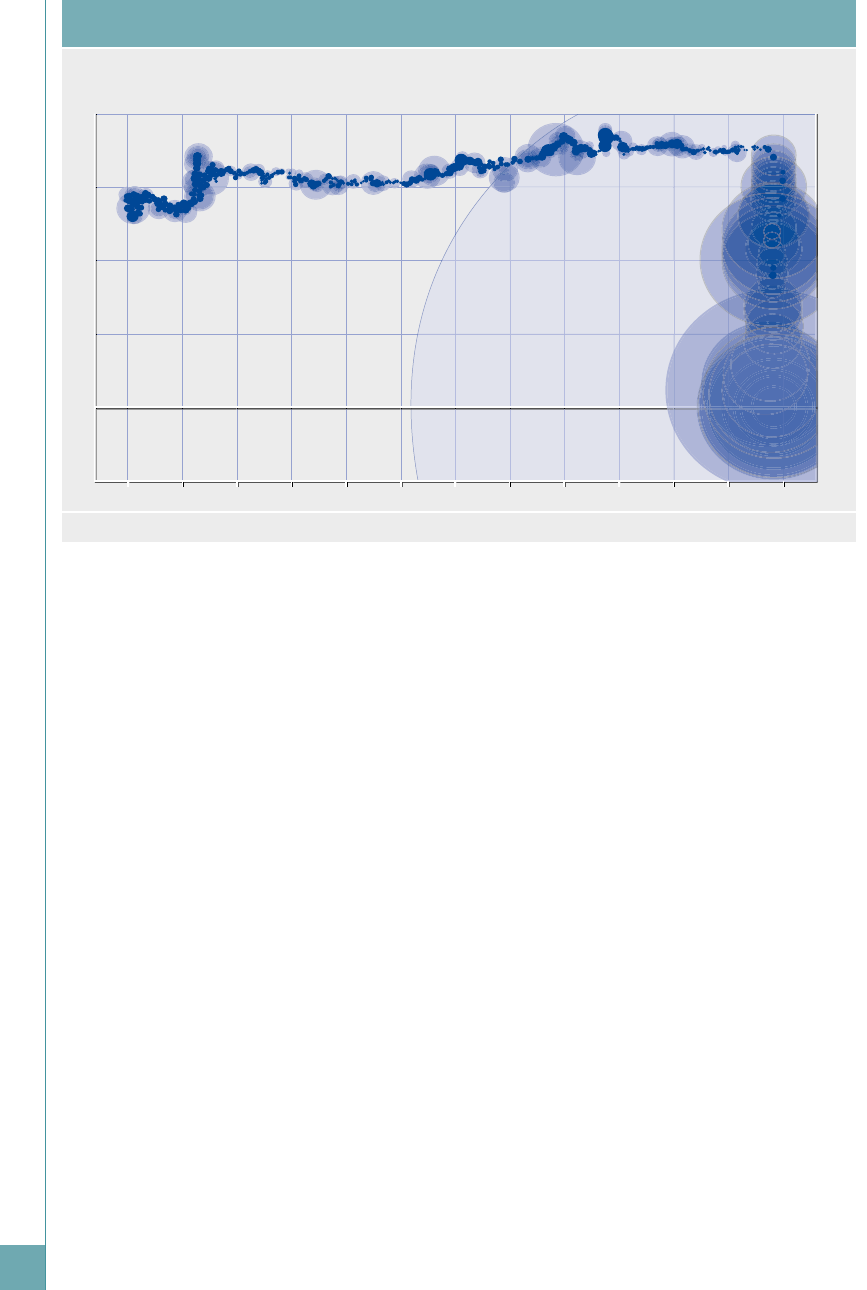

Chart 5 Total Bitcoins over time

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

2009 2015 2021 2027 2033 2039 2045 2051

Total Bitcoins (in millions)

Source: Bitcoin.

25

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

25

3 CASE STUDIES

25

needed). As explained on its website,

8

the rate of block creation is approximately constant over

time:sixperhour,oneeverytenminutes.However,thenumberofBitcoinsgeneratedperblockis

settodecreasegeometrically,witha50%reductioneveryfouryears.Theresultisthatthenumber

of Bitcoins in existence will reach 21 million in around 2040. From this point onwards, miners are

expectedtonancethemselvesviatransactionfees.Infact,thiskindoffeecanalreadybecharged

byaminerwhencreatingablock.

The fact that the supply of money is clearly determined implies that, in theory, the issuance of money

cannotbealteredbyanycentralauthorityorparticipantwantingto“print”extramoney.According

to Bitcoin supporters, the system is supposed to avoid ination, as well as the business cycles

originatingfromextensivemoneycreation.However,thesystemhasbeenaccusedofleadingtoa

deationaryspiral.ThetotalsupplyofBitcoinsisexpectedtogrowgeometricallyuntilitreaches

anitelimitof21million.If,however,thenumberofBitcoinusersstartsgrowingexponentially

for any reason, and assuming that the velocity of money does not increase proportionally,

along-termappreciationofthecurrencycanbeexpectedor,inotherwords,adepreciationofthe

pricesofthegoodsandservicesquotedinBitcoins.Peoplewouldhaveagreatincentivetohold

Bitcoinsanddelay theirconsumption,therebyexacerbatingthedeationary spiral.Theextentto

which this could be a problem in reality is not clear. Two remarks should be made. Firstly, as

highlightedbytheEconomist(2011a),thedeationhypothesisentailsanassumptionwhichisnot

realisticatthisstage,i.e.thatmanymorepeoplewillwanttoreceiveBitcoinsinreturnforgoodsor

inexchangeforpapermoney.However,Bitcoinisstillquiteimmatureandilliquid(the6.5million

Bitcoins are shared by 10,000 users) which is a clear disincentive for its use. Secondly, Bitcoin

isnotthecurrencyofacountryorcurrencyareaandisthereforenotdirectlylinkedtothegoods

and services produced in a specic economy, but linked to the goods and services provided by

merchantswhoacceptBitcoins.Thesemerchantsmayalsoacceptanothercurrency(e.g.USdollars)

andtherefore,thefactthatdeationisanticipatedcouldgiverisetoasituationwheremerchants

adaptthepricesoftheirgoodsandservicesinBitcoins.

3.1.4 SECURITY INCIDENTS AND NEGATIVE PRESS

From time to time, Bitcoin is surrounded by controversy. Sometimes it is linked to its potential for

becomingasuitablemonetaryalternativefordrugdealingandmoneylaundering,asaresultofthe

highdegreeofanonymity.

9

On other occasions, users have claimed to have suffered a substantial

theftofBitcoinsthroughaTrojanthatgainedaccesstotheircomputer.

10

The Electronic Frontier

Foundation,whichisanorganisationthatseekstodefendfreedominthedigitalworld,decidednot

toacceptdonationsinBitcoinsanymore.Amongthereasonsgiven,theyconsideredthat“Bitcoin

raises untested legal concerns related to securities law, the Stamp Payment Act, tax evasion,

consumerprotectionandmoneylaundering,amongothers”.

11

However, practically identical problems can also occur when using cash, thus Bitcoin can be

considered to be another variety of cash, i.e. digital cash. Cash can be used for drug dealing and

moneylaunderingtoo;cashcanalsobestolen,notfromadigitalwallet,butfromaphysicalone;and

cash can also be used for tax evasion purposes. The question is not so much related to the format of

moneyassuch(physicalordigital),butrathertotheusepeoplemakeofit.Nevertheless,iftheuseof

digitalmoneyinitselfcomplicatesinvestigationsandlawenforcement,specialrequirementsmaybe

needed. Therefore, the real dimension of all these controversies still needs to be further analysed.

See 8 https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Controlled_ination

See,forinstance,http://gawker.com/5805928/the-underground-website-where-you-can-buy-any-drug-imaginable9

Oneuserclaimstohavelost25,000BitcoinsworthUSD500,000.Seehttp://forum.bitcoin.org/index.php?topic=16457.010

AnnouncedbyCindyCohn,LegalDirectorfortheFoundation.Seehttp://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2011/06/eff-and-bitcoin11

26

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

2626

Bitcoin has also featured in the news, in particular following a cyberattack perpetrated on

20 June 2011, which managed to knock the value of the currency down from USD 17.50 to

USD 0.01 within minutes. Apparently, around 400,000 Bitcoins (worth almost USD 9 million)

wereinvolved.AccordingtocurrencyexchangeMt.Gox,oneaccountwithalotofBitcoinswas

compromisedandwhoeverstoleit(usingaHongKongbasedIPtologin)rstsoldalltheBitcoins

inthere,onlytobuythembackagainimmediatelyafterwards,withtheintentionofwithdrawingthe

coins. The USD 1,000/day withdrawal limit was active for this account and the hacker was only able

toexchangeUSD1,000worthofBitcoins.Apartfromthis,nootheraccountswerecompromised,

andnothingwaslost.

12

Chart6showstheevolutionofBitcoin’sexchangerateontheMt.Goxexchangeplatformduring

the hours of the incident, and is also the expression of how an immature and illiquid currency can

almostcompletelydisappearwithinminutes,causingpanictothousandsofusers.

Inaddition,theperpetratorhackedintotheMt.Goxdatabase,gainingaccesstousernames,e-mail

addressesandhashedpasswordsforthousandsofusers.Mt.Goxreactedbyclosingthesystemfor

a few days and by promisingthat the transactions carried out by the hacker wouldbe reversed.

Bitcoin defenders claim that the Bitcoin system did not fail. The problem was related to a particular

tradingplatform–Mt.Gox–whichdidnothavestrongenoughsecuritymeasures.

In a more recent case (May 2012), the exchange platform Bitcoinica lost 18,547 Bitcoins from

its deposits following a cyberattack, in which sensitive customer data might also have been

obtained.

13

SeeMt.Goxpressreleasehttps://mtgox.com/press_release_20110630.html12

Seehttp://www.nextra.com/News/Fullstory.aspx?newsitemid=2371313

Chart 6 Mt.Gox exchange rate on 20 June 2011

20

15

10

5

0

-5

20

15

10

5

0

-5

20 00 04 08 12 16 20 00 04 08 12 16 20

x-axis: time (UTC)

y-axis: price ($/BTC)

Source: Mt.Gox.

27

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

27

3 CASE STUDIES

27

Another recurrent issue is whether Bitcoin works likea Ponzi scheme or not. Users gointo the

systemby buying Bitcoins againstreal currencies, butcanonly leave andretrievetheir funds if

other users want to buy their Bitcoins, i.e. if new participants want to join the system. For many

people, this is characteristic of a Ponzi scheme. The US Securities and Exchange Commission

denesaPonzischemeinthefollowingterms:

APonzischemeisaninvestmentfraudthatinvolvesthepaymentofpurportedreturnstoexisting

investors from funds contributed by new investors. Ponzi scheme organizers often solicit new

investorsbypromisingtoinvestfundsinopportunitiesclaimedtogeneratehighreturnswithlittle

ornorisk.InmanyPonzischemes,thefraudstersfocusonattractingnewmoneytomakepromised

paymentstoearlier-stage investors and tousefor personal expenses, insteadofengaging in any

legitimateinvestmentactivity.

14

On the one hand, the Bitcoin scheme is a decentralised system where – at least in theory – there

isnocentralorganiserthatcanunderminethesystemanddisappearwithitsfunds.Bitcoinusers

buyandsellthecurrencyamongthemselveswithoutanykindofintermediationandtherefore,it

seemsthatnobodybenetsfromthesystem,apartfromthosewhobenetfromtheexchangerate

evolution (just as in any other currency trade) or those who are hard-working “miners” and are

thereforerewardedfortheircontributiontothesecurityandcondenceinthesystemasawhole.

Moreover,theschemedoesnotpromisehighreturnstoanybody.AlthoughsomeBitcoinusersmay

trytoprotfromexchangerateuctuations,Bitcoinsarenotintendedtobeaninvestmentvehicle,

just a medium of exchange. On the contrary, Gavin Andresen, Lead Developer of the Bitcoin

virtual currency project, does not hesitate to say that “Bitcoin is an experiment. Treat it like you

wouldtreatapromisinginternetstart-upcompany:maybeitwillchangetheworld,butrealisethat

investingyourmoneyortimeinnewideasisalwaysrisky”.

15

In addition, Bitcoin supporters claim

that it is an open-source system whose code is available to any interested party.

However,itisalsotruethatthesystemdemonstratesaclearcaseofinformationasymmetry.Itis

complex and therefore not easy for all potential users to understand. At the same time, however,

userscaneasilydownloadtheapplicationandstartusingiteveniftheydonotactuallyknowhow

thesystemworksandwhichriskstheyareactuallytaking.Thisfact,inacontextwherethereisclear

legaluncertaintyandlackofcloseoversight,leadstoahigh-risksituation.Therefore,althoughthe

currentknowledgebasedoesnotmakeiteasytoassesswhetherornottheBitcoinsystemactually

workslikeapyramidorPonzischeme,itcanjustiablybestatedthatBitcoinisahigh-risksystem

foritsusersfromanancialperspective,andthatitcouldcollapseifpeopletrytogetoutofthe

system and are not able to do so because of its illiquidity. The fact that the founder of Bitcoin uses

apseudonym–SatoshiNakamoto–andissurroundedbymysterydoesnothingtohelppromote

transparency and credibility in the scheme.

Alltheseissuesraiseseriousconcernsregardingthelegalstatusandsecurityofthesystem,aswell

asthenalityandirrevocabilityofthetransactions,inasystemwhichisnotsubjecttoanykindof

publicoversight.InJune2011twoUSsenators,CharlesSchumerandJoeManchin,wrotetothe

Attorney General and to the Administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration expressing

theirworriesaboutBitcoinanditsuseforillegalpurposes.MrAndresenwasalsoaskedtogivea

presentation to the CIA about this virtual currency scheme.

16

Further action from other authorities

can reasonably be expected in the near future.

Seehttp://www.sec.gov/answers/ponzi.htm14

Seehttp://gavinthink.blogspot.com/2011/06/that-which-does-not-kill-us-makes-us.html15

AccordingtoFinextra(http://www.nextra.com/news/fullstory.aspx?newsitemid=22644)andChapman(2011).16

28

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

2828

3.2 THE SECOND LIFE SCHEME

3.2.1 BASIC FEATURES

Second Life is a virtual community created by

Linden Lab (Linden Research, Inc.), a privately

held company based in San Francisco. The

company, whose CEO is Philip Rosedale, has

developed a ‘massively multiplayer online

role-playing game’, which was launched in

June 2003. It is based on a three-dimensional

modellingtoolthatallowsuserstobuildvirtual

objects.

The main idea behind Second Life is to create an

opportunityforpeople to change allthethings

about their life that they dislike. This virtual

world mirrors the real world, and its users –

called residents – interact with each other and

perform their daily tasks and activities just as

they do in real life (e.g. meeting friends, playing, writing or organising a party). They can also

engageinabusinessprojectorbuyahouse,acarorayacht.Inthisvirtualworld,usersdonothave

to face any kind of restriction.

Users need to install software on their computers and open a free Second Life account to make use

of the virtual world. A premium membership option (USD 9.95 per month, USD 22.50 quarterly,

or USD 72 per year), which extends access to an increased level of technical support, is also

available.Chart7showsthattheaveragenumberofusersloggingineachmonthisquitestable

atjustaboveonemillionpermonth.Thenumberofusersregisteredon28November2011was

morethan26million.Oncetheyhavesubscribed,usersbecomeresidentsandtheycanstartusing

thisonlineworldbycreatingavatars–theresidents’digitalrepresentation–whichmaytakeany

formtheychoose(human,animal,vegetable,mineral,oracombinationthereof)oreventheirown

imageinreallife.Aresidentaccountcanonlyhaveoneavataratatime.Nevertheless,residentsare

freetochangetheformoftheiravatarsatanytime.Residentscanearnmoneyindifferentways.

Theycansellwhatevertheyareabletocreate;theycanalsoprotfromtheirpreviousinvestments

(e.g.buyingahouseandthensellingitatahigherprice),buttheycanalsowinprizesinevents.

Inaddition,premiumaccountsreceiveaweeklyautomaticgrantof300LindenDollarspaidintothe

member’s avatar account.

3.2.2 SECOND LIFE ECONOMY

IntheSecondLifeeconomy,peoplecreateitems,suchasclothes,gamesorspacecraft,andthen

sell them within the community. Most of the money earned comes from the virtual equivalent of

landspeculation,aspeopleleaseislandsorerectbuildingsandthenrentthemouttoothersata

premium.

17

The economy within Second Life works in a similar way to any other economy in the

world, but exhibits three specic features. Firstly, it is a self-sufcient economy, i.e. a closed

economy where no activity is conducted with the outside; secondly, it is only focused on virtual

goods and services; and thirdly, it is generated and takes place entirely within Linden Lab’s

infrastructure. Everything else is quite similar to a normal economy. Second Life has its own

The Economist (2006).17

Chart 7 Average number of users logging

in each month

(thousands)

800

900

1,000

1,100

800

900

1,000

1,100

2010 2011

Source: Reports on Second Life Economy.

29

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

29

3 CASE STUDIES

29

economic agents (buyers, sellers and even an

online-community regulator) interacting in its

economic system and conducting commerce;

the factors of production are the same as in a

real economy (labour, capital and land); and the

price system is the mechanism in charge of

resource allocation. As a consequence, Second

Life’soutputcanbemeasuredand,accordingto

one estimate, the value of transactions increased

by 94% on a year-on-year basis in 2009.

Residents exchange goods and services worth

around USD 600 million each year and the

SecondLifeeconomyisestimatedtobebigger

in terms of GDP than 19 countries, including

Samoa.

18

AlthoughSecond Lifeseems tohave

the largest output among the virtual

communities, it is obvious that it is still far from

reachingasignicantvolume.SecondLifehas

itsownnancialsystemandexchangemarket.

In 2006 this virtual community also started

issuing itsownvirtualcurrency,called Linden

Dollars(L$).TheLindenDollarisavirtualcurrencythathastobepurchased(e.g.bycreditcard

orPayPal)beforebeingusedtobuyvirtualgoodsandservicesinsidetheSecondLifecommunity.

Inprinciple,real-worldgoodsandservicescannotbepurchasedwithLindenDollars.

This currency can be bought through Linden Lab’s currency brokerage, the LindeX Currency

Exchange,orotherthird-partycurrencyexchanges.Itcanalsobeconvertedbackintorealmoney.

AscanbeseeninChart8,theexchange rate has been quitestable,ataroundL$260=USD1.

ThisisbecauseLindenLabtriestokeepvolatilitylowbyinjectingnewLindenDollarsasdemand

increases.Therefore,itcanbesaidthattheLindenDollaris,tosomeextent,peggedtotheUSdollar.

AccordingtotheSecondLifeEconomyinQ42010report,thetotalLindeXvolumetradedin2010

wasnearlyUSD119million,2.8%higherthanin2009.

AlthoughSecondLife’seconomyexistsonline,companiessellingvirtualgoodsandservicescan

makerealprots.Moreover,asreportedbyElliot(2008),somecompaniesarealsostartingtouse

theonlineworldformerchandisingtheirproducts.Companies,suchasCisco,Reuters,Dell,Sun

Microsystems,Adidas,StarwoodHotelsandToyotahavemadeuseoftheSecondLifeenvironment

for marketing and brand-building purposes. In addition, some universities (e.g. Chicago Law

School,theUniversityofIdaho and New York University)andpoliticians(e.g.HillaryClinton)

have a presence in Second Life.

3.2.3 MONETARY ASPECTS

Second Life also has its own monetary policy, based on the supply of Linden Dollars by Linden

Lab.AsexplainedbyPengandSun(2009),thetotalamountofthisvirtualcurrencyincirculation

dependsonthreeelements:a)thenetsellingamountofLindenDollarstradedbyLindenLabon

LindeXwithusers,whichissimilartotheopenmarketoperationsconductedbycentralbanksin

the real world; b) Linden Lab’s revenue in Linden Dollars from island sales and land rental to

Fleming(2010).18

Chart 8 Average exchange rate

(Linden Dollar/US dollar)

240

245

250

255

260

265

270

275

280

240

245

250

255

260

265

270

275

280

2009 2010 2011

Source: Reports on Second Life Economy.

30

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

3030

residents; and c) the Linden Dollar grant paid

by Linden Lab to premium members. Only in

therstandlastcasesisnewmoneycreated.In

its terms of service, the company clearly states

that “Linden Dollars are available for purchase

or distribution at Linden Lab’s discretion, and

are not redeemable for monetary value from

Linden Lab”. Furthermore, “Linden Lab has

the right to manage, regulate, control, and/

or modify the license rights underlying such

LindenDollars(…)”.Inpractice,itcanbesaid

thatLindenLabactsastheissuingbankinthe

Second Life environment. It can change the

quantity of money in circulation as it wants and

decide how to allocate these resources.

Chart 9 shows the evolution of the supply of

Linden Dollars and, in order to provide an

overview of the dimension of this virtual money

supply, it is compared with the supply of US

dollars. So far money supply is negligible and

cannotthereforeinuenceanystate’seconomy.

LindenLab’smoney issuing policywithinthe virtual communityhasnot escaped criticism.For

example, Beller (2007) suggests that they may be creating an endogenous shock since Linden

LabnancesitsdecitbycreatingnewLindenDollars.AdecitinSecondLifeoccurswhenthe

weeklyLindenDollargrantsthatLindenLabpaystopremiumaccountholdersexceeditsrevenue

from land rentals and other administrative services it provides to residents. Every time Linden Lab

runsadecit,thesupplyofmoneyinstantlyincreasesbyanequivalentamount.Asaconsequence,

tonanceitsdecit,LindenLabis“printing”LindenDollars,ratherthanborrowingthemfromthe

market,i.e.itisnotincreasingitsstockofpublicdebt,insteadcreatingnewmoneywhichisnot

supported by real money.

Thismoneycreationprocess,whicharticiallyinatesthemoneysupply,couldbecreatingaboom

withinSecondLife’seconomythatcouldleadtoarecessionifLindenLabisforcedtotightenits

moneysupply.Inthissituation,alossofcondenceandasuddendeprecationoftheLindenDollar

would be expected, causing all users that are involved in the virtual community to suffer some

losses.Inanycase,itisimportanttohighlightthatthiswouldonlyhaveanegativeimpactwithin

the virtual community and for its users. Its effects would not spread to the real economy.

3.2.4 ISSUES WITH SECOND LIFE

SecondLifeisfocused on thevirtualworld,butthis does notmeanthateverythingis virtual in

this community. There are real economic transactions behind Second Life and there are also real

issuesandproblemsthatarise.WithinSecondLife,LindenLabistheonlyauthorityandregulator.

To some extent they also oversee the system, but without the involvement of any public authority.

It is not even clear if any authority even needs to be involved. In fact, in the current situation, any

potentialissuewithinthisvirtualmarketplacecanperhapsberegardedinthecontextofconsumer

protectionrights.

Chart 9 Supply of Linden Dollars

and US dollars

(in US dollar millions)

Linden dollars (left-hand scale)

US dollars (right-hand scale)

2009 2010 2011

32

30

28

26

24

22

20

10,000,000

9,500,000

9,000,000

8,5000,000

8,000,000

7,500,000

7,000,000

Sources: Second Life and Federal Reserve.

Notes: The US money stock is measured by M2 (not seasonally

adjusted).Theguresrefertothelastmonthofeveryquarter.

31

ECB

Virtual currency schemes

October 2012

31

3 CASE STUDIES

31

SecondLifegoesbeyondaregularonlinegame.Fromaneconomicandnancialpointof view,

Second Life exhibits specic features that link this virtual world with the real world. Firstly,

as stressed above, some companies are starting to use the online world for merchandising their

products.Also,virtualbusinesseshavebeensetupandobtainrealprotsinSecondLife.Secondly,

itseemsthatsomeresidentshavebeenabletoearnsignicantamountsofrealmoneywiththeir

nancialtransactions,butintheprocesshaveassumedhighlevelsofrisk.Inthepast,someSecond

Life banks started offering very high interest rates on deposits, which motivatedmany users to

changerealmoneytobuyLindenDollarsanddeposittheminthesebanks.Suchahighyieldina

non-regulatedenvironmentraisedsome concerns withregardtothepossibilitythatSecondLife,

or some users of Second Life, might actually be working like Ponzi schemes.

19

One case even

appearstoconrmthis:GinkoFinancial,abankthatusedtopayveryhighinterestratestodepositors

(theycouldostensiblyreachupto69.7%peryear),wentbankruptinAugust2007,causinglosses

of around USD 750,000 to some Second Life residents. After the collapse, Linden Lab introduced a

ruleprohibitingusersfromofferinginterestoranydirectreturnoninvestment(whetherinLinden

Dollars or any other currency) from any object, such as an ATM, located in Second Life, without

proofofanapplicablegovernmentregistrationstatementornancialinstitutioncharter.

20

Second Life’s real estate market has also developed quite quickly, basically fuelled by land

speculation.In2006,BusinessweekmagazinehighlightedthecaseofAnsheChung,aresidentwhose

realnameisAilinGraef.Apparently,thiswoman(wholivesinFrankfurt)hasbecometherstonline

guretoachieveanetworthofmorethanonemillionUSdollars;thishasbeenachievedfromprots

entirely earned inside Second Life. This fortune is especially remarkable because she developed it