Do “happier” countries have lower levels of

depression and anxiety – A study to explore the

association between the World Happiness

Index and the prevalence of depression and

anxiety disorders by Country.

TOTAL WORD COUNT:

6,000 (EXCLUDING REFERENCES, APPENDIX AND FIGURES)

DONG ZHENG

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the help I have received during writing of this essay. Word

cannot express my gratitude to Dr Charlotte O’Brien, who have guided me

through this process and provided valuable support at every stage.

My dear friends, Dr Xi mian Quan and Dr Mohammed Zeina played pivotal roles

in the formulation of my final essay. I could not have done this without their

inputs in reviewing many drafts of my review essay and the late-night feedbacks.

Their encouragements and emotional support throughout this journey have

carried me to the final stages.

I would also like to thank my close friend Mr HuiKai Shi, who let me bounce off

many ideas during the initial stages of the essay. As well as providing feedbacks

on the early drafts of this review essay.

Abstract:

Introduction: It is a common preconception that countries with higher levels of

“happiness” would have lower levels of mental diseases. This essay interprets

happiness as subjective wellbeing and explores its association with depression and

anxiety disorders.

Aims: Investigate the relationship between the world happiness index and the

prevalence of depression and anxiety

Method: Statistical analysis are employed in this review. Scatter graphs were plotted

for the WHI and its six explanatory factors against depression and anxiety prevalence

to investigate the correlation. Subsequent Pearson’s correlation coefficient is calculated

using STATA.

Findings: No linear correlation is observed between the WHI and the prevalence of

depression and anxiety. A positive correlation was shown between the explanatory

factors GDP per capita, social support and healthy life expectancy at birth with anxiety

and depression prevalence. However, due to the nature of mental health and its

diagnosis criterias, the current epidemiological data for mental disease do not reflect

the actual global mental health burden.

Conclusion: The essay found some overlaps between subjective well-being and its

constituents with the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders. Yet, other

determinants also has a strong influence on the development of anxiety and depression.

Introduction:

Ever since human existence, attempts have been made to define, explore, and attain

happiness. Research on the linguistic and historical roots of happiness suggests that the

concept has gradually evolved from the meaning of luck and fortune in ancient China,

to its contemporary usage in the English language to describe one’s inner positive

feelings,[1] often conceptualised as affective wellbeing – the fulfilment of pleasure and

avoidance of misery.

In the healthcare context, happiness is used interchangeably with subjective wellbeing.

[2] The literature agrees on the necessity of experiencing positive emotions in achieving

happiness but also mentions the essence of perceiving one’s life as meaningful and

worthwhile,[3] this can be conceptualised as eudemonic wellbeing- pursuance of

purpose and meaning in life. Moreover, Greek philosophy, Christianity, and Buddhism

emphasise the importance of self-development, mindfulness, and mental health rather

than objective social or economic circumstances of the individual in achieving

happiness. Both affective and subjective well-being are interlinked with life satisfaction

experienced in daily life. Since 2012, an annual publication called The World Happiness

Report (WHR) has attempted to quantify the concept of happiness by ranking life

evaluations by country. Its aims are to understand and measure global wellbeing and

encourage governments across the globe to centre sustainable development goals

around “happiness”. The report discusses a two-way interaction that links happiness

with personal factors, and mental and physical health. [4]

Intuitively, one would assume that the concept of happiness is not compatible with

depression and anxiety disorders, as these diseases are characterised by prolonged low

mood, feelings of guilt, reduced self-esteem, and irritability, while happiness is more

commonly associated with joy, contentment, and satisfaction. Therefore, a natural

conjecture is presumed that societies with high levels of happiness would have a low

occurrence of affective mental disorders. Numerous studies have shown that people

who experience happiness tend to be less prone to mental illnesses, whlist breeding

success across multiple life domains, including health, income, friendships, and

marriage. [5]

The ambivalence between happiness and depression also captured the attention of the

media. In 2019 BBC Worklife published the news article titled: “being depressed in the

“world’s happiest country,” reporting the mental health challenges in Finland, [6] the

nation that topped the world happiness index in 2019. However, there is minimal

academic research linking the association between happiness and mental health.

Despite the presence of ICD-10 and DSM-5 standard diagnostic criteria, there lacks a

guideline that accounts for biopsychosocial differences. These diagnostic criteria and

supplementary questionaires are mostly subjective unidimensional measures. Mental

disorders, more than any other branches of medicine, are closely intertwined with social

determinants of health, and their diagnosis can have a heavy reliance on cultural

influences. Social determinants including inequalities in income and education can

influence one susceptibility to mental illnesses through epigenetic interactions with

their environment.[7] The mission to fully understand and tackle mental illness remains

an urgent global health priority.

Background:

World Happiness Report – W hat is it

Similar to medical literature [2], the World Happiness Report (WHR) uses subjective

well-being in relation to the concept of happiness. The WHR measure of subjective

well-being are based on life evaluations, which is defined as “a reflective assessment

of a person’s life or some aspects of it.”[8] The life evaluation measure is based on the

Gallup world poll surveys, which select 500-3000 individual responses annually from

each country across the globe to provide a representative sample. The respondents are

asked to evaluate their life positions using the Cantril ladder scale, which ranks the best

possible life as 10 and the worst as 0. A population-representative average is then

generated for each country. The ranking uses data average of the the 3 years prior to the

year it is evaluating. The reason behind this is that not every country is surveyed

annually, and increased sample size would give more precise estimates. [9] Thus, the

world happiness index is effectively a ranking of average life evaluation scores by

country.

World Happiness report – explanatory factors

The WHR uses six key comparable national variables to explain the difference in

average life evaluation for the countries included in the ranking.These are continuous

numerical values to illustrate the likely two-way correlations between the variables and

life evaluations. The six variables are the perception of corruption, generosity, freedom

to make life choices, healthy life expectancy at birth, social support, and GDP per capita.

The final seventh variable, Dystopia- a hypothetical country with the world’s lowest

value (1.83) for the six variables is included to allow a positive calculated contribution

for every actual country. [9] Dystopia is used as a benchmark for comparison among

different countries to provide an explanation for the rankings of the average life

evaluation in the annual world happiness report.

The six factors used to explain the average life evaluation rankings are chosen to

reflect a component of happiness. Intriguingly, they have a degree of overlap with the

determinants of depression and anxiety disorders. For example, social support can offer

both direct protection through positive social relationships and indirectly acting as a

buffer against stressful events. In children and young adults, positive family support

appeared to be the most protective factor against depression.[10] Youths need to rely

on their parents to sustain their basic needs, including both emotional support and

material resources. In addition, family support can enhance self-esteem in young adults

and decrease negative self-evaluation and the subsequent depressive symptoms. [11] In

adults, spousal support is the strongest protective factor against depressive symptoms.

Both giving and receiving support from spouses are related to increased positive mood,

less anxiety, and depression. [12]

Freedom to make life choices correlates closely with mental health symptoms.

Cognitive impairment, referring to deficits in problem-solving, short-term and working

memory, and visual and auditory processing is a defining feature of major depression,

[13] which affects short-term and long-term decision making, restricting the patient

from their free will. Furthermore, in forensic psychiatry, free will is an essential

requirement for moral responsibility, and that free will can be compromised by mental

disorders.[14]

Generosity can influence the maintenance of positive emotions, stress reduction and

enhances one’s sense of purpose. Generosity is the act of altruism, a form of positive

social connection and empathy. The 2015 WHR involved neuroimaging studies that

have shown activation of the ventral tegmental area and ventral and dorsal striatum

when individuals donate and receive money. The ventral tegmental area is associated

with reward and motivation, while the ventral striatum plays a key role in emotion and

learning. Surprisingly, these areas are more active when people donated money than

when they received it. [15] These findings rehearse philosophical ideas of eudemonic

wellbeing, which emphasise the importance of self-development and living a

meaningful life.

GDP per capita is a good measure of the country’s wealth and average individual

income, but it may not provide valid insight into the distribution of wealth in society.

Countries with a high income per capita tends to have a well-developed welfare system,

which includes a good education system, and a universal healthcare system. These

factors are strong influences on the development and progression of depression and

anxiety disorders. Research has identified how social-economic variation can create a

treatment gap for mental diseases. Analysis showed around 75% of the population in

middle and low-income countries have not received any forms of treatment for their

depression, because of a lack of trained staff and resources, and the social stigma

associated with the illness. [16] This was supported by WHO estimates in 2019 which

also found that 80% of patients suffering from mental health disorders are not able to

afford treatment or receive psychiatric help because the country does not have universal

healthcare. [17]

Life expectancy at birth can also be reflective of a country’s healthcare developments

and population living conditions. More importantly, depression and anxiety disorders

are one of the leading causes of the global disease burden, accounting for 7% of total

global DALY (disability-adjusted life years) and 19% of disabilities lived

worldwide.[18] One retrospective using US mortality data demonstrated that people

with depression/anxiety died on an average of 7.9 years earlier than their non-diseased

counterparts.[19] These findings provide strong evidence that mental health can affect

one’s overall quality of life and give rise to health complications, which subsequently

influence their life expectancy.

Corruption may seem unrelated to depression and anxiety at first glance, but discretely

it is related to the other variables discussed and can indirectly affect social determinants

of mental illness. For example, the main form of corruption is direct financial bribery.

The loss of income and the arbitrariness nature of bribery can create anxiety and other

negative emotions in the briber. Also, in some countries, violence or harassment used

to popularise the bribery culture aggravates feelings of helplessness and erodes the

accountability of the governing structures and essential services, including healthcare,

social services, and education. [20] The corruption of government officials means less

economic input for public structures. Consequently, fewer resources and medical

training are provided, causing mentally ill patients not being offered treatments or not

treated promptly. Furthermore, the loss of income may render one’s labour meaningless.

The feeling of despair coupled with an inability to provide for one’s family can induce

pessimistic thoughts, leading to vicious cycle breeding symptoms of depression and

anxiety disorders. This phenomenon is described by economists as the “depression

poverty trap.”

World Happiness Report – Reports on mental health

Since its first publication in 2012, mental health has been a recurrent theme in world

happiness reports. For example, the 2012 WHR has attempted to address the question

of how important mental health is in explaining the variation of happiness within any

particular country. The reports suggest that the indirect effects of mental health also

have a significant effect on later life. For example, adolescents who have experienced

depression are more likely to experience unemployment, teenage pregnancy, criminal

records, poor physical health, low income, and worse educational performance. All of

these consequences have a direct effect on happiness, both on the individual and the

community. [4] The 2013 WHR dedicates a specific chapter to mental health and

unhappiness. The report showed mental health to be the biggest and the single most

important determinant of happiness for individuals but are mostly ignored by

policymakers. [21] It argues that mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety not

only restrict individual fulfilment in life but also cause difficulties in communication

and the formation of relationships, resulting in social isolation. In addition, severe

mental illness can affect one' s mental capacity, robbing individuals of their natural

thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. In addition, the report indicates that mental health

problems are the most important explanatory variable, exceeding the impacts of

physical health problems, income, and unemployment. The report concludes that

mental health is closely tied with global happiness in two ways. “Better treatment for

mental health would improve happiness directly, and improving happiness in other

ways would reduce the frequency of mental illness.” [21]

The discussion around mental health continued in 2018 and 2019 WHR, where the

Easterlin paradox drew attention. The Easterlin paradox describes the phenomenon in

USA where the income per capita in has doubled since 1972, but subjective wellbeing

remains roughly unchanged or declined. The report proposes a causal relationship

between non-income-related social determinants and increased levels of obesity,

substance abuse disorders, and major depressive disorders.[22] More strikingly, these

factors are most likely to be interlinked. Obesity was found to increase the risk of

depression, most prominently patients with clinically diagnosed depression. [23] One

of the many implications of addictive behaviours is the development and worsening of

mood and anxiety disorders. Substance abuse can lead to mood dysregulation and

secondary acute stress events, giving rise to clinical depression. Conversely, mood

disorders can also provoke addictive behaviours as depression patients attempt to “self-

medicate” out of their dysphoria and resort to medication abuse. [24]

The 2022 report examined people’s emotional experiences and wellbeing through

analysing text communications on social media. As emotions are not mere internal

feelings, but also social in nature. Therefore, positive and negative emotions can be

spread through social media, influencing other people’s emotions. [25, 26] The findings

revealed there was a large upsurge of anxiety-related terms on Twitter in all countries

shortly before and with the onset of lockdowns. In addition, the rise in anxiety was more

significant in countries with greater number COVID-19 cases. In comparison, the

phrases on social media expressing anger decreased and sadness increased two weeks

later. [9]

Study Design

Statstical analysis

The study is facilitated using the statistical analysis functions on STATA (17.0) software

[27], where scatter plots and pearson coefficients are used to analysis the raw data. The

process is summarised by the algorithm in figure 1.

The Pearson’s coefficient (r) is used in the statistical analysis to measure of the strength

of the linear association between the two variables. The first part of the analysis

involves examining the relationship between the average life evaluation from 2017

WHR and the WHO estimates of the prevalence of anxiety and depression. The

Pearson’s correlation coefficient is determined at the 95% significance level with the

dependent variable being the 2017 world happiness index, and the independent variable

being the prevalence of depression and anxiety respectively. The null and alternative

hypothesis for this analysis is stated below:

H0: There is no correlation (r=0 or no pattern on scatter graph) between average life

evaluations and depression and anxiety prevalence.

H1: There is a correlation (r≠ 0 or pattern identified scatter graph) between average

life evaluations and depression and anxiety prevalence.

The second and third part of the statistical analysis aims to determine the correlation

between the six explanatory factors and the prevalence of depression and anxiety. In

these two parts of the statistical measurements, the significance level of 95% is used

with the dependent variables being anxiety and depression prevalence respectively and

the independent variable being the explanatory factors for the 2017 WHI rankings. The

null and alternative hypothesis for the second and third regression analysis is stated

below:

The null hypothesis for the second part of the statistical analysis:

H0: There is no correlation (r=0) between the explanatory factors for the 2017 WHI

and depression prevalence.

H1: There is a correlation (r≠ 0) between the explanatory factors for the 2017 WHI

and depression prevalence.

The null hypothesis for the third part of the statistical analysis:

H0: There is no correlation (r=0) between the explanatory factors for the 2017 WHI

and anxiety prevalence.

H1: There is a correlation (r≠ 0) between the explanatory factors for the 2017 WHI

and anxiety prevalence.

Figure 1 Flowchart showing the algorithm for the statistical analysis procedure

Data collection

The data variables for the statistical analysis are based on the 2017 World Happiness

Report [8] and WHO global health estimates of depression and other common mental

health disorders published in 2017. [28] The WHO estimates are the most up-to-date,

global epidemiological estimations by country on depression and anxiety disorders. [29]

The WHO estimations are synthesised from the Global Burden Disease study [30] to

provide a country-specific estimation of depression and anxiety prevalence for the year

2015. Similarly, the 2017 WHI is produced from an average of 2014-2016 Cantril

ladder scores. The average life evaluation values and the explanatory factors are taken

from chapter 2, online data in the appendix of the 2017 World Happiness Report. [8]

The WHO 2017 global mental health estimates report did not include Taiwan, Hong

Kong, Kosovo, North Cyprus, and Palestine Territories. [28] To minimise the statistical

bias of introducing new datasets from other estimates and literature, these countries are

excluded from the analysis.

Study design limitations

The most significant limitation for ecological studies is ecological fallacy. Therefore,

the findings from this study on the relationship between happiness prevalence levels of

depression and anxiety may not apply at individual levels. In addition, this is an

observational study, which makes it difficult to draw causational conclusions, Maybe

there are relationships between the investigated variables, but they are complex and non

linear.

Results

Quantitative analysis

Examining the scatter plots, no visible linear relationship can be observed between the

World Happiness Index scores and the prevalence of depression and anxiety. Neither of

the two scatter plots demonstrates a strong positive or negative correlation between the

variables.

From the scatter plot, we can observe the majority of the countries have a WHI score

between 3-7 and an anxiety prevalence of 2-6% of the population. There are several

outliers for the scatter plot comparing anxiety prevalence and WHI, which defies the

applicability of Pearson’s correlation coefficient, as the outliers would distort the

measure of linearity between the variables. The data plots were more spread out for the

depression prevalence, where most of the countries measured had a depression

prevalence of 3-6% of the total population. No linear relationship can be identified

between the independent and dependent variables, so it does not satisfy the criteria for

determining Pearson’s correlation coefficient. No alternative patterns (e.g., quadratic

curvature) can be observed from the scatter plots in figure 2. Therefore, we would

accept the null hypothesis based on the scatter plot, where no correlation between the

world happiness index and the prevalence of depression and anxiety can be observed.

We conclude that no correlation between the world happiness index and the prevalence

of depression and anxiety can be observed.

F

igure 2

Scatter plot showing the association between world happiness index

and depression/anxiety prevalence

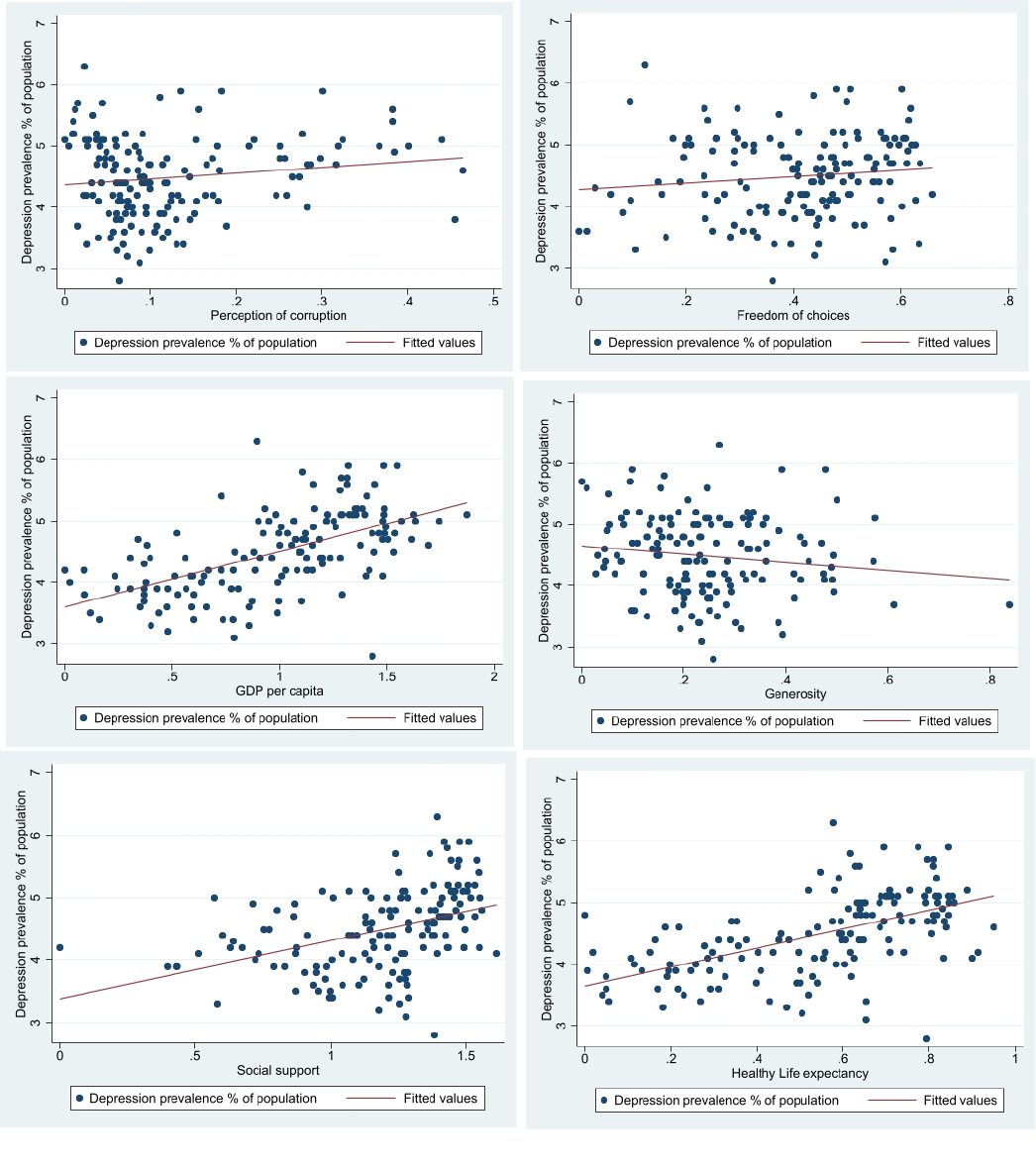

For the scatter plots in figure 3, the independent variables plotted on the X axis are the

explanatory factors for the WHI, and the dependent variable plotted on the Y axis is the

depression prevalence estimates. The scatter plots failed to show an observable

correlation between perception of corruption, freedom of choice, generosity, and the

independent variable of depression prevalence. A moderate positive correlation can be

identified for the GDP per capita and healthy life expectancy at birth, which has a

Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.579 (p=0.00 r

2

= 0.335) and 0.553 (p=0.00

r

2

=0.306) respectively (see appendix). The GDP per capita can explain 33.5% of the

variation in depression prevalence, while healthy life expectancy at birth can explain

30.6% of the variation in depression prevalence. In comparison, social support only had

a weak correlation of 0.411 (p=0.00 r

2

=0.169) with the prevalence of depression, which

explains 16.9% of the independent variable. These findings imply that with the increase

in GDP per capita, healthy life expectancy, and social support, there is a rise in

depression prevalence. The null hypothesis is rejected and the alternative hypothesis

is accepted at the 95% significance level, which suggests there is a correlation between

the dependent variables comprising social support, GDP per capita, life expectancy, and

the independent variable of depression prevalence.

Figure 3 Scatter plots showing the association between the explanatory factors of WHI and depression prevalence

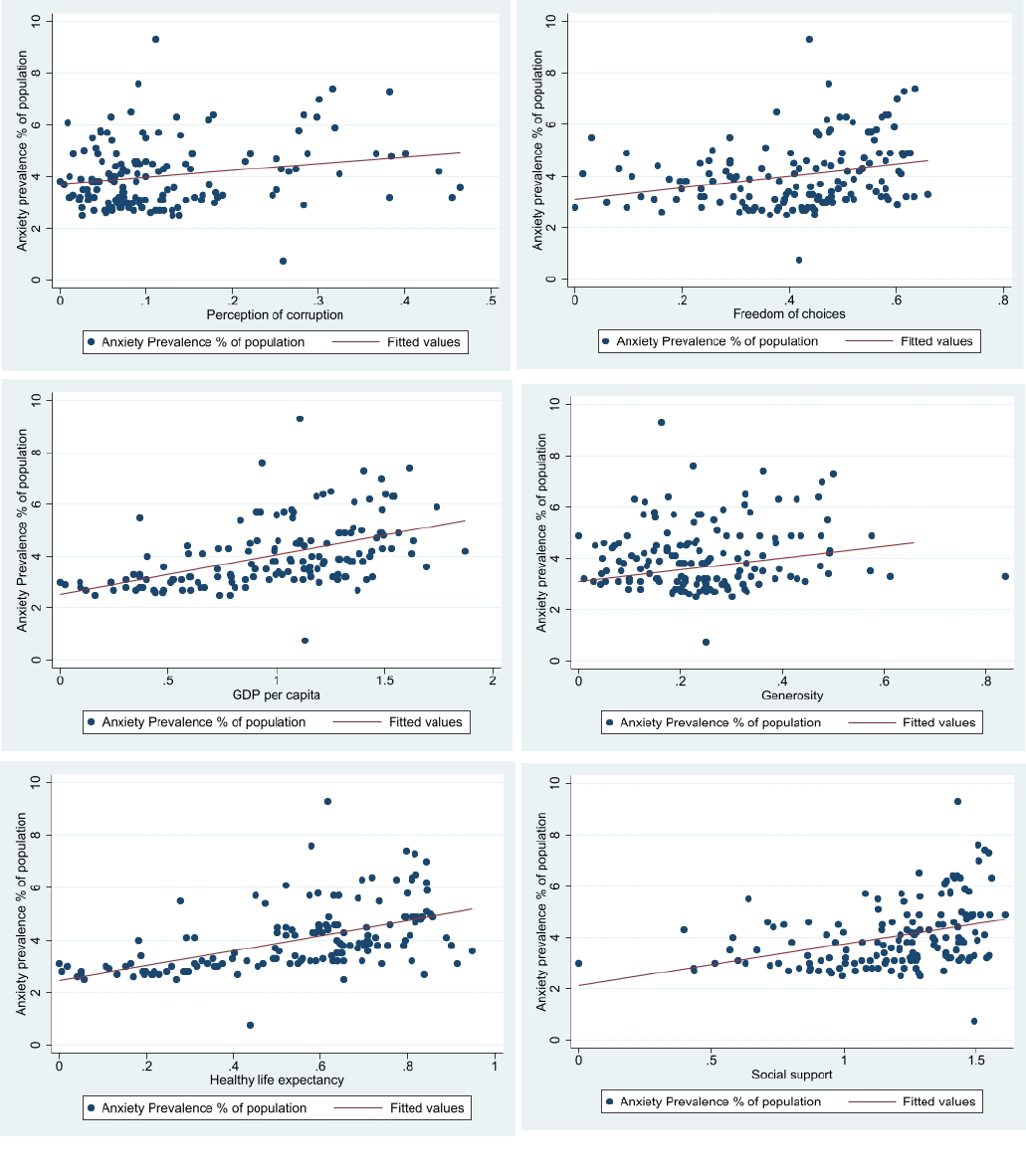

Figure 4 plots anxiety prevalence as the dependent variable and the explanatory factors

for happiness as the independent variable. There is no observable correlation between

perception of corruption, freedom of choices, generosity, and the independent variable

of the prevalence of anxiety. There is a weak positive correlation between social support

and anxiety prevalence with an r-value of 0.366 (p=0.00 r

2

= 0.134), which explains

13.4% of the variation in anxiety prevalence in different countries. A moderate

correlation is identified for the dependent variables of healthy life expectancy at birth

and GDP per capita and the independent variable, which has a correlation coefficient

value of 0.539(p=0.00 r

2

= 0.291) and 0.507(p=0.00 r

2

=0.257) respectively (see

appendix). These statistical findings imply that healthy life expectancy explains 29.1%

of the variation in anxiety prevalence, while GDP per capita can explain 25.7% of the

variation in the independent variable. In summary, the scatter plots and the correlation

coefficient suggest surprisingly, that with the increase in social support, healthy life

expectancy at birth, and GDP per capita, there is an increase in anxiety prevalence in

the population. Therefore, we can reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative

hypothesis at the 95% significance level.

Figure

4 Scatter plots showing the association between the explanatory factors for happiness and anxiety prevalence

Discussion

GDP, life expectancy, social support, and mental health

The result from the analysis implies countries with higher GDP per capita, healthy life

expectancy at birth, and high levels of social support have a higher prevalence of

depression and anxiety disorders in the population. These findings paradoxically

suggest that high income, longer life expectancy, and good levels of social support can

become risk factors for the development of depression and anxiety.

Contrary to the statistical findings, popular preconceptions and research studies

acknowledged that wealth and high income are protective against depressive disorders.

A multivariate logistic regression study based on the national survey in the US showed

higher predicted probabilities of depressive symptoms for low family saving groups

compared to high family saving groups at every income level. Even after controlling

for other confounding factors including gender, age, education, marital status, ethnicity,

and family income, a person with low family savings has 1.49 times (OR 1.49 1.01-

2.21 95% CI) higher odds of having depressive symptoms than individuals with high

family savings (above $20,000). A person in a family with an annual income less than

$20,000 is 2.74 more likely to have depression symptoms than a person in families with

an annual income greater than $75,000 (OR 2.74 1.87-4.01 95% CI)[31]. In addition,

accumulating evidence has demonstrated that poverty and mental health conditions are

traveling partners. Negative income shocks, such as job loss and excessive debts can

worsen a person’s mental status through resultant worries and uncertainties. While the

provision of social welfare, insurance, and health can lower depression and anxiety

occurrence. [32] Research where providing free health insurance worth $550-$750 a

year to low-income individuals showed a reduction in depression rate by a quarter

within a few months, this effect cannot be fully explained by a mere improvement in

affordable healthcare. [33]

However, GDP per capita may not reflect accurately one’s income. High GDP per

capita is a crude measure of modernisation, a sociological transformation associated

with greater inequality, more life stresses, malnourishment from over-consumption of

processed foods, and social isolation. For example, China has undergone a rapid social

transformation in the past decades. But social disparities, unemployment, domestic

migrations, and high-intensity overtime work have become common problems. One of

the main costs of becoming the world’s second-largest economy is the mental health of

the younger generations. A retrospective study showed that Chinese individuals born

after 1966 were 22.4 times more likely to suffer from a depressive episode than the

generations born before 1937. This finding was unforeseen, considering those born in

1937’s China would have experienced Japanese invasion, civil warfare, and political

instability. The sudden increase in depressive episodes between the two generations

reflects the mental stresses present in modern societies. [34]

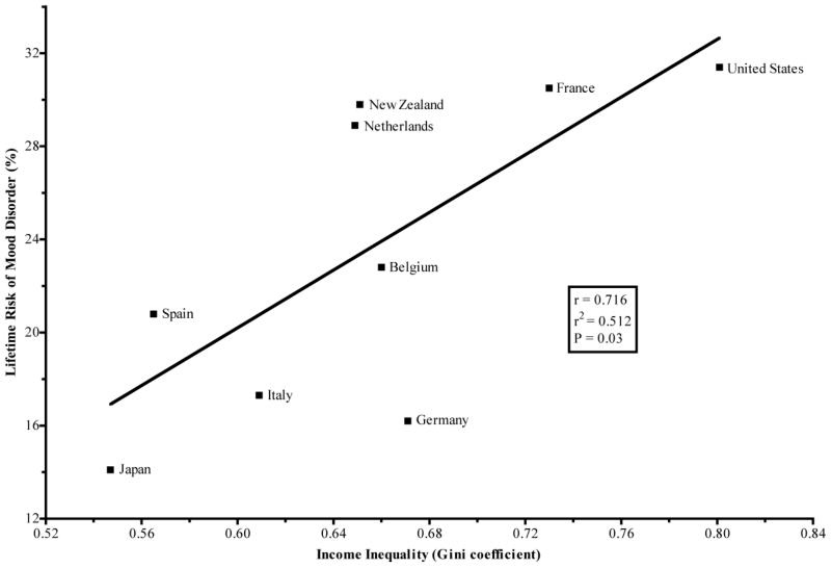

Furthermore, Similar results to my statistical analysis were found in Hidaka’s paper.

A correlation between lifetime risk of mood disorders and GDP per capita showed a

statistical significance (r= 0.464 r

2

= 0.215 p= 0.06) (Figure 5). [35] My results from

assessing the correlation between GDP per capita and depression prevalence (r=0.579

r

2

= 0.335 p=0.00) were supportive of Hidaka’s findings.

In addition, inequality generated from the modernisation process predisposes

individuals to higher levels of social distrust, excessive worrying, and competition, all

risk factors for the development of depression and anxiety. Figure 6 is a scatter graph

plotting lifetime risk for mood disorders against each country’s Gini coefficient. A

strong positive correlation can be observed from the graph (r=0.716) accounting for

51.2% of the results (r

2

= 0.512 p=0.03). [35] Therefore, while high individual income

and wealth appear to be protective of one’s mental health, GDP per capita reflects the

country’s modernisation which unfortunately is accompanied by greater social and

economic inequalities and stresses from modern-day living.

Figure

5 – Scatter graph showing the correlation between lifetime

risk of mood disorder (%)

and GDP per capita ($1k).

(36)

Figure 6 - Scatter graph showing the correlation between lifetime risk of mood disorder (%) and

GDP per capita ($1k) (36)

Interestingly, our results also found a positive correlation between increases in healthy

life expectancy at birth and prevalence levels of depression and anxiety. This was a

strange finding as the mental disease is associated with 7% of DALYs and 19% of YLDs

in 2016,[18] so one should expect an inverse correlation between the two variables.

Research has shown that individuals with mental disorders have an increased risk of

premature mortality. The risk of early death was significantly higher in people of all

ages with a mental disorder. In the Danish population cohort study, it was identified that

males and females suffering from mood affective disorders had a reduced life

expectancy of 7.9 and 6.2 years respectively compared to their healthy counterparts.

Using the Poisson regression models, the mortality rate ratio for mood disorders is 1.92

(95% CI 1.91-1.94), this means that there are 92% more cases of premature deaths due

to mood disorders in the cohort assessed compared to the national population. [36]

One possible explanation for our finding is that anxiety and depression have become

common in old age. Old age is accompanied by various changes in brain structure and

neuropathways, as well as health changes from the aging process such as reduced

mobility and increased loneliness. [37] New onset anxiety disorders, previously thought

to be non-existent in the older population, have now become better recognised by

geriatricians over the past years. A study examining the age at onset in older adults with

GAD, showed a bimodal distribution with 57% of participants reporting an early-onset

(before 50) and 43% reporting a late-onset (after 50). [38] Likewise, in a separate

retrospective study with a mean age of 74.1 years, 46% were late onset and the mean

age of disease diagnosis is 48.8 years. Furthermore, for patients with both diagnosis of

GAD and MDD, typically GAD diagnosis precedes MDD, [39] which is in concordance

with clinical practice as both mental conditions shares some common risk factors and

one can influence the development of the other. Therefore, a plausible explanation for

the positive correlation between life expectancy and depression and anxiety prevalence

could be the increased recognition of late-onset anxiety and depression disorders.

From the results of this study, only a weak positive correlation is identified between

social support and depression and anxiety prevalence. While existing literature suggests

that social support is a protective factor against mental illness through positive social

relationships and indirectly as buffers against social stresses. [10-12, 40-43]

Depression and anxiety-affected individuals can experience cognitive impairments,

which means they may not recognise or even deny that they have a mental disorder. In

communities with a good level of social support, people look out for each other and are

form initimate social relationships, communicating their inner feelings with friends and

families. Therefore, signs of mental diseases are quickly picked up, and timely medical

help sought. Conversely, for individuals who are not supported by their social relations,

their mental health symptoms may not be picked up resulting in underdiagnosis.

Furthermore, social support is integral to health promotion, addressing individuals'

physical and emotional needs, as well as spreading medical information to their social

groups. Poor levels of social support can lead to underdiagnosis and ineffective health

promotions, which inaccurately show low mental health prevalence.

Moreover, unlike GDP per capita and healthy life expectancy, which are objective

measurements. The measurement of social support is calculated from the binary

response to the Gallup World Poll question: “If you were in trouble, do you have

relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need, or not?” The

question is highly subjective and one’s definition of terms such as “trouble,” “friends

you can count on” and “whenever you need” may vary within different cultures and

social circumstances. For example, in Asian cultures people tend to be more reserved

about their opinions and personal feelings, individuals are confronted with their roles

in the social hierarchy. Japanese culture emphasises the concept of “Omoiyari”

(altruistic sensitivity), which promotes empathy and social responsibility in Japanese

society. However, when taken to an extreme, some individuals decide to not “trouble”

others to ensure they will not be “troubled” in the future. [44] Furthermore, in some

parts of the world, society may be based on favouritism, asking for a favour may require

a return in favour in the future, so people may be less inclined to seek help from friends

and relatives. Therefore, the influence of social support on mental health may vary

within different cultures and societies.

Likewise, corruption, generosity, and freedom to make choices are also derived from

binary responses to one or two GWP survey questions.[8] These measures could be

more representative of well-being and have greater relevance to mental health if it is

formulated from a series of well-defined question answered using a numerical scale.

Perhaps this also explains the weak or no correlation in these between subjective

measures and mental health prevalence compared to the moderate correlation seen in

GDP per capita and life expectancy.

Cultural influences on mental health and diagnostic

standardisation

Around 85% of the world’s population lives in middle and low-income countries - [45]

mental diseases accounts for 8.8% and 16.6% of the total burden of disease in middle

and low-income countries respectively. [46] Middle and low-income countries are more

economically vulnerable compared to high-income nations, so their residents are more

likely to be exposed to financial stressors including hunger, job loss, and inability to

cover healthcare fees, which increases their risk of mental health diseases. These factors

may not be fully represented in the WHO estimations for mental health and the WHR.

The diagnosis of depression and anxiety disorders relies heavily on questionnaires and

the clinical experience of the psychiatrist. Although guidance such as ICD-10 and

DSM-5 is widely used, there is no internationally recognised “gold standard” in

diagnosing anxiety and depression. For example, alongside the use of ICD and DSM

criteria, China also uses CCMD-3 (Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders) to reach

a diagnosis. Interestingly, the CCMD-3 also included conditions such as “Qigong

Deviation” (defined as the perception of uncontrolled “Qi” around the body, which also

presents with insomnia symptoms), and mental disorders caused by superstitions

(which can also affect the patient’s cognitive functions). [47] A systematic review

assessing the usage of mental health clinical practice guidelines in Japan showed that

there has been little research into the implementation, barriers, and dissemination of the

guidelines in Japan, [48] suggesting a mixture of mental health guidelines may have

been used.

The problem with questionnaires such as PHQ-9 and GAD-7 is individuals from

different cultural and social backgrounds tend to report their symptoms differently. For

example, because Asian traditions view the body and the mind as unitary rather than

dualistic, Asian patients are more likely to focus on their somatic symptoms and do not

acknowledge emotional symptoms. [49] These findings were also supported by a series

of studies on Hong Kong patients. Although patients were entirely aware of the

emotional difficulties and stresses rooted in social relationships that can result in their

physical and mental symptoms. Most patients selectively present their symptoms and

tend to only target somatic symptoms in healthcare settings. [50, 51] Furthermore,

studies showed that Asian American patients have a lower utilisation rate of mental

health services because they do not approach healthcare services until later stages of

the help-seeking process. Asians with Schizophrenia were contained within the family

or communities and generally did not encounter mental health services until three years

after the onset of psychotic symptoms. In comparison, their Caucasian and African

American counterparts entered the mental health system within an average of one and

one and half years respectively after the onset of symptoms. [52] Another study also

found that students with Asian ancestry on US campuses were less like to use mental

health services compared to students of European origin. [53] These complications

from cultural influences are likely to result in underdiagnosis depending on cultural

backgrounds.

Unlike in Western countries, anxiety and depression can be unfamiliar terms for a

medical condition. For example, in China, depression is labelled “shen jing shuai ruo”

(neurasthenia). In India, “ghabrahat” (peculiar restlessness), and “pelo y tata” (heart too

much) in Botswana. [54] Similarly, in Zimbabwe, many depressed individuals assign

their symptoms to supernatural causes, overthinking, “deep sadness” or social stressors.

[55] Furthermore, in Zimbabwe, patients tend to move to traditional healthcare systems

after consultation with primary care providers, only a few turns to a mental health

professional. The primary health practitioners and traditional healers typically prescribe

non-specific treatments such as analgesics, hypnotics, or vitamins for their somatic

symptoms, limited numbers of patients are recognised for their psychiatric conditions

and are transferred to mental health workers for a better outcome. [54] These practices

due to cultural and social norms consequently lead to an underdiagnosis and

undertreatment of mental diseases.

Another factor that leads to the underdiagnosis of mental disorders is social stigma.

Studies found that Asian cultural norms do not recognise the importance of mental

disorders.[56] Furthermore, people from Eastern cultures reported that being mentally

ill was shameful [57], and they have less favourable help-seeking attitude toward

mental health support and lower levels of interpersonal openness compared to their

European American counterparts. [58] Research suggests there is greater stigma

associated with depressive disorders in Eastern nations, this partly stems from the lack

of economic contributions by the depressed individuals in the family, which further

exacerbates their depression. [59] Moreover, in countries with more dominant mental

health stigma beliefs, the likelihood of patients receiving mental health help from

trained professionals is reduced, and individuals also refrain from approaching general

practitioners regardless of their own stigma beliefs. [60]

In summary, mental illnesses are complex and their development is heavily influenced

by cultural, social, economic, and political circumstances. Although ICD-10 and DSM-

5 guidelines are acknowledged by mental health professionals globally, there is much

regional variation in criteria and clinical practices when diagnosing mental illnesses.

This complexity makes it extremely difficult to provide an accurate estimation of cases

of depression and anxiety disorders on a global scale. WHO estimates are unlikely to

be representative of the actual mental health burden worldwide. Consequently, the

relationship between “happiness” and depression and anxiety may not have been fully

addressed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review has provided an insight into the relationship between

“happiness” and the prevalence levels of anxiety and depression. Contrary to common

preconceptions - “happier” countries have lower levels of depression and anxiety

disorders. The statistical analysis showed no linear association between a country’s

world happiness index scores and its depression and anxiety prevalence. Nevertheless,

positive Pearson correlations were identified between the explanatory factors: GDP per

capita, healthy life expectations at birth, social support, and the prevalence of

depression and anxiety.

However, these findings do not explain the relationship between subjective wellbeing

and mental illnesses. There are several confounding factors behind these correlations,

such as inequality of income due to the modernisation process, increased recognition

of late-onset anxiety and depression disorders, and the survey design of the Gallup

World Poll. But the most important drawback of this epidemiological study is the

inability to compare mental health statistics. The WHO global mental health estimates

were not a comprehensive estimate of the true mental health burden. The true cases of

depression and anxiety are underestimated due to cultural influence and the lack of a

global “gold standard” in diagnosis.

All in all, both the topics of mental health and the concept of happiness are convoluted

in nature. The two topics have many overlapping influencing factors, but no direct

correlation can be observed between WHI scores and the prevalence of depression and

anxiety levels at the country level. Further research is required before the application

of WHI in psychiatric and public health studies.

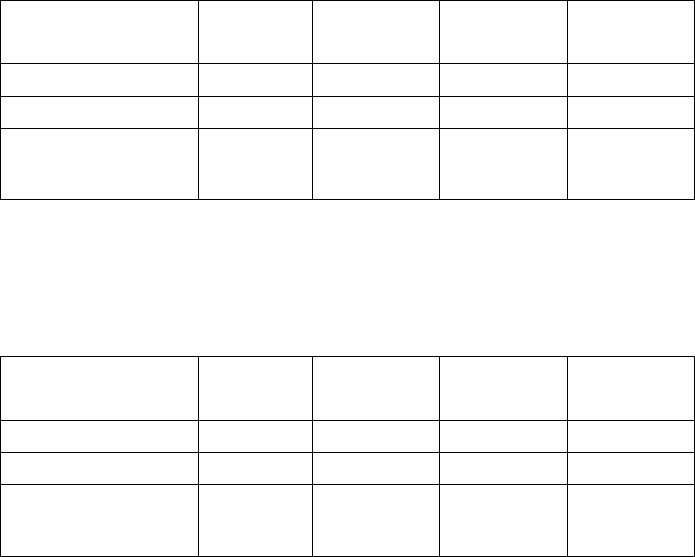

Appendix:

Table 1 – Pearson’s correlation coefficient between depression prevalence and GDP per capita,

Life expectancy and Social support.

Depression

Prevalence

r

r

2

p=

n=

GDP per capita

0.579

0.335

0.00

150

Life expectancy

0.553

0.306

0.00

150

Social Support

0.411

0.169

0.00

150

Table 2 – Pearson’s correlation coefficient between anxiety prevalence and GDP per capita,

Life expectancy and Social support.

Anxiety

Prevalence

r

r

2

p=

n=

GDP per capita

0.507

0.257

0.00

150

Life expectancy

0.539

0.291

0.00

150

Social Support

0.366

0.134

0.00

150

References

1. Oishi, S., et al.,

Concepts of Happiness Across Time and

Cultures.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,

2013.

39(5): p. 559- 577.

2. Steptoe, A.,

Happiness and Health.

Annual Review of

Public Health, 2019.

40(1): p. 339- 359.

3. Muthuri, R.N.D.K., F. Senkubuge, and C. Hongoro,

Determinants of happiness among healthcare

professionals between 2009 and 2019: a systematic

review.

Humanities and Social Sciences

Communications, 2020.

7(1): p. 98.

4. Helliwell, J.a.L., Richard and Sachs, Jeffrey (eds.)

World

happiness report 2012

, in

World happiness report

, J.

Sachs, Editor. 2012, The Earth Institute, Columbia

University: New York, USA. .

5. Lyubomirsky, S., L. King, and E. Diener,

The benefits of

frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to

success?

Psychol Bull, 2005. 131(6): p. 803- 55.

6. Savage, M.

Being depressed in the 'world's happiest

country'

. BBC Worklife 2019 [cited 2022 21/06];

Available from:

https://answers.frederick.edu/citations/faq/304627

.

7. Michael T. Compton, M.D. , M.P.H. , and and Ruth S.

Shim, M.D., M.P.H.,

The Social Determinants of Mental

Health.

FOCUS, 2015. 13(4): p. 419- 425.

8. Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J.,

World Happiness

Report 2017

, in

World Happiness Report

, R.L. John

Helliwell, Jeffrey Sachs, Jan- Emmanuel De Neve,

Haifang Huang and Shun Wang, Editor. 2017,

Sustainable Development Solutions Network.: New

York.

9. John Helliwell, R.L., Jeffrey D. Sachs, Jan- Emmanuel De

Neve, Lara B. Aknin, Shun Wang; and Sharon Paculor,

World Happiness Report 2022

, in

World Happiness

Report

, R.L. John Helliwell, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Jan-

Emmanuel De Neve, Lara B. Aknin, Shun Wang; and

Sharon Paculor, Editor. 2022, Sustainable Development

Solutions Network: New York.

10. Gariépy, G., H. Honkaniemi, and A. Quesnel- Vallée,

Social support and protection from depression:

systematic review of current findings in Western

countries.

British Journal of Psychiatry, 2016. 209(4): p.

284- 293.

11. Ioannou, M., A.P. Kassianos, and M. Symeou,

Coping

With Depressive Symptoms in Young Adults: Perceived

Social Support Protects Against Depressive Symptoms

Only Under Moderate Levels of Stress.

Frontiers in

psychology, 2019.

9: p. 2780- 2780.

12. Biehle, S.N. and K.D. Mickelson,

Provision and receipt

of emotional spousal support: The impact of visibility

on well- being.

Couple and Family Psychology:

Research and Practice, 2012.

1(3): p. 244.

13. Lam, R.W., et al.,

Cognitive dysfunction in major

depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial

functioning and implications for treatment.

Can J

Psychiatry, 2014.

59(12): p. 649- 54.

14. Meynen, G.,

Free will and mental disorder: exploring

the relationship.

Theor Med Bioeth, 2010. 31(6): p.

429- 43.

15. Moll, J., et al.,

Human fronto- mesolimbic networks

guide decisions about charitable donation.

Proc Natl

Acad Sci U S A, 2006.

103(42): p. 15623- 8.

16. Evans- Lacko, S., et al.,

Socio- economic variations in

the mental health treatment gap for people with

anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results

from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys.

Psychol Med, 2018.

48(9): p. 1560- 1571.

17. World Health, O.,

The WHO special initiative for mental

health (2019- 2023): universal health coverage for

mental health

. 2019, World Health Organization:

Geneva.

18. Rehm, J. and K.D. Shield,

Global Burden of Disease and

the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders.

Curr

Psychiatry Rep, 2019.

21(2): p. 10.

19. Pratt, L.A., et al.,

Excess mortality due to depression

and anxiety in the United States: results from a

nationally representative survey.

Gen Hosp Psychiatry,

2016.

39: p. 39- 45.

20. Sharma, S., S. Singhal, and F. Tarp,

Corruption and

mental health: Evidence from Vietnam.

Journal of

Economic Behavior & Organization, 2021.

185: p. 125-

137.

21. Helliwell, J.F., Richard Layard, and Jeffrey Sachs, eds,

World Happiness Report 2013

, in

World Happiness

Report

R.L.a.J.S. John Helliwell, Editor. 2013, UN

Sustainable Development Solutions Network.: New

York.

22. Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J.,

World Happiness

Report 2018

, in

World Happiness Report

, R.L.a.J.D.S.

John F. Helliwell, Editor. 2018, Sustainable

Development Solutions Network: New York.

23. Luppino, F.S., et al.,

Overweight, obesity, and

depression: a systematic review and meta- analysis of

longitudinal studies.

Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2010. 67(3):

p. 220- 9.

24. Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J.,

World Happiness

Report 2019

, in

World Happiness Report

R.L.a.J.D.S.

John F. Helliwell, Editor. 2019, Sustainable

Development Solutions Network: New York.

25. Goldenberg, A., et al.,

Collective Emotions.

Current

Directions in Psychological Science, 2020.

29(2): p.

154- 160.

26. Rimé, B.,

Emotion Elicits the Social Sharing of Emotion:

Theory and Empirical Review.

Emotion Review, 2009.

1(1): p. 60- 85.

27. StataCorp.

Stata Statistical Software: Release 17.

[17.0]

2021.

28. Organization, W.H.,

Depression and other common

mental disorders: global health estimates.

, W.H.

Organization, Editor. 2017.

29. Saloni Dattani, H.R.a.M.R.

Mental Health

. Our World in

Data 2021 [cited 2022 02/05]; Available from:

https://ourworldindata.org/mental- health

.

30. Network, G.B.o.D.C.,

Global Burden of Disease Study

(GBD 2019)

. 2019, Institute for Health Metrics and

Evaluation (IHME): Seattle , United States.

31. Ettman, C.K., G.H. Cohen, and S. Galea,

Is wealth

associated with depressive symptoms in the United

States?

Ann Epidemiol, 2020. 43: p. 25- 31.e1.

32. Ridley, M., et al.,

Poverty, depression, and anxiety:

Causal evidence and mechanisms.

Science, 2020.

370(6522): p. eaay0214.

33. Finkelstein, A., et al.,

THE OREGON HEALTH

INSURANCE EXPERIMENT: EVIDENCE FROM THE FIRST

YEAR.

Q J Econ, 2012. 127(3): p. 1057- 1106.

34. Lee, S., et al.,

Lifetime prevalence and inter- cohort

variation in DSM- IV disorders in metropolitan China.

Psychological Medicine, 2007.

37(1): p. 61- 71.

35. Hidaka, B.H.,

Depression as a disease of modernity:

Explanations for increasing prevalence.

Journal of

Affective Disorders, 2012.

140(3): p. 205- 214.

36. Plana- Ripoll, O., et al.,

A comprehensive analysis of

mortality- related health metrics associated with mental

disorders: a nationwide, register- based cohort study.

The Lancet, 2019.

394(10211): p. 1827- 1835.

37. de Lijster, J., et al.,

The age of onset of anxiety

disorders in samples from the general population: A

meta- analysis.

European Psychiatry, 2016. 33: p. S56-

S57.

38. Le Roux, H., M. Gatz, and J.L. Wetherell,

Age at onset

of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults.

Am J

Geriatr Psychiatry, 2005.

13(1): p. 23- 30.

39. Lenze, E.J., et al.,

Generalized anxiety disorder in late

life: lifetime course and comorbidity with major

depressive disorder.

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2005.

13(1): p. 77- 80.

40. Boudreault- Bouchard, A.M., et al.,

Impact of parental

emotional support and coercive control on

adolescents' self- esteem and psychological distress:

results of a four- year longitudinal study.

J Adolesc,

2013.

36(4): p. 695- 704.

41. Okun, M.A. and V.M. Keith,

Effects of positive and

negative social exchanges with various sources on

depressive symptoms in younger and older adults.

J

Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 1998.

53(1): p. P4- 20.

42. Simon, R.W. and A.E. Barrett,

Nonmarital romantic

relationships and mental health in early adulthood:

does the association differ for women and men?

J

Health Soc Behav, 2010.

51(2): p. 168- 82.

43. Stafford, M., et al.,

Positive and negative exchanges in

social relationships as predictors of depression:

evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Aging.

J Aging Health, 2011.

23(4): p. 607- 28.

44. Hara, K.,

The Concept of Omoiyari (Altruistic Sensitivity)

in Japanese Relational Communication.

Intercultural

Communication Studies, 2006.

15.

45. Jacob, K.S., et al.,

Mental health systems in countries:

where are we now?

Lancet, 2007. 370(9592): p. 1061-

77.

46. Organization, W.H.,

The global burden of disease: 2004

update

. 2008: World Health Organization.

47. Chen, Y.F.,

Chinese classification of mental disorders

(CCMD- 3): towards integration in international

classification.

Psychopathology, 2002. 35(2- 3): p. 171-

5.

48. Tamura, N.,

[Current Status of Clinical Practice

Guidelines for Mental Health in Japan].

Seishin

Shinkeigaku Zasshi, 2017.

119(3): p. 151- 157.

49. Lin, K.- M. and F. Cheung,

Mental Health Issues for

Asian Americans.

Psychiatric Services, 1999. 50(6): p.

774- 780.

50. Cheung, F.M. and B.W. Lau,

Situational variations of

help- seeking behavior among Chinese patients.

Comprehensive Psychiatry, 1982.

51. Cheung, F.M.,

An overview of psychopathology in

Hong Kong with special reference to somatic

presentation.

Chinese culture and mental health, 1985:

p. 287- 304.

52. Lin, T.- Y. and M.- C. Lin,

Service delivery issues in

Asian- North American communities.

The American

Journal of Psychiatry, 1978.

53. Han, M. and H. Pong,

Mental health help- seeking

behaviors among Asian American community college

students: The effect of stigma, cultural barriers, and

acculturation.

Journal of College Student Development,

2015. 56(1): p. 1- 14.

54. Patel, V., et al.,

Depression in developing countries:

lessons from Zimbabwe.

Bmj, 2001. 322(7284): p. 482-

4.

55. Abas, M.A. and J.C. Broadhead,

Depression and anxiety

among women in an urban setting in Zimbabwe.

Psychol Med, 1997.

27(1): p. 59- 71.

56. Lee, S., et al.,

Model Minority at Risk: Expressed Needs

of Mental Health by Asian American Young Adults.

Journal of Community Health, 2008.

34(2): p. 144.

57. Kung, W.W.,

Cultural and practical barriers to seeking

mental health treatment for Chinese Americans.

Journal of Community Psychology, 2004.

32(1): p. 27-

43.

58. Masuda, A. and M.S. Boone,

Mental Health Stigma,

Self- Concealment, and Help- Seeking Attitudes among

Asian American and European American College

Students with No Help- Seeking Experience.

International Journal for the Advancement of

Counselling, 2011.

33(4): p. 266- 279.

59. Krendl, A.C. and B.A. Pescosolido,

Countries and

Cultural Differences in the Stigma of Mental Illness: The

East–West Divide.

Journal of Cross- Cultural

Psychology, 2020.

51(2): p. 149- 167.

60. Bracke, P., K. Delaruelle, and M. Verhaeghe,

Dominant

Cultural and Personal Stigma Beliefs and the Utilization

of Mental Health Services: A Cross- National

Comparison.

Frontiers in Sociology, 2019. 4.