KYDD, A., FLEMING, A., PAOLETTI, I. and HVALIČ-TOUZERY, S. 2020. Exploring the terms used for the oldest old in the

gerontological literature. Journal of aging and social change [online], 10(2), pages 53-73. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.18848/2576-5310/CGP/v10i02/53-73

Exploring the terms used for the oldest old in the

gerontological literature.

KYDD, A., FLEMING, A., PAOLETTI, I. and HVALIČ-TOUZERY, S.

2020

This document was downloaded from

https://openair.rgu.ac.uk

T

h

e

J

o

u

r

n

a

l

o

f

Ag

i

n

g

a

n

d

So

c

ial

Change

VOLUME 10 ISSUE 2

AGINGANDSOCIALCHANGE.COM

_________________________________________________________________________

Exploring Terms Used for the

Oldest Old in the Gerontological Literature

ANGELA KYDD, ANNE FLEMING, ISABELLA PAOLETTI, AND SIMONA HVALIČ-TOUZERY

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

https://agingandsocialchange.com

ISSN 2576-5310 (Print)

ISSN 2576-5329 (Online)

https://doi.org/10.18848/2576-5310/CGP (Journal)

First published by Common Ground Research Networks in 2020

University of Illinois Research Park

2001 South First Street, Suite 202

Champaign, IL 61820 USA

Ph: +1-217-328-0405

https://cgnetworks.org

The Journal of Aging and Social Change

is a peer-reviewed, scholarly journal.

COPYRIGHT

© 2020 (individual papers), the author(s)

© 2020 (selection and editorial matter),

Common Ground Research Networks

All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study,

research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the applicable

copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any

process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions

and other inquiries, please contact cgscholar.com/cg_support.

Common Ground Research Networks, a member of Crossref

EDITOR

Andreas Motel-Klingebiel, Linkoping University, Sweden

ACTING DIRECTOR OF PUBLISHING

Jeremy Boehme, Common Ground Research Networks, USA

MANAGING EDITOR

Helen Repp, Common Ground Research Networks, USA

ADVISORY BOARD

The Aging and Social Change Research Network recognizes the

contribution of many in the evolution of the Research Network. The

principal role of the Advisory Board has been, and is, to drive the

overall intellectual direction of the Research Network. A full list of

members can be found at https://agingandsociety.com/about/advisory-

board.

PEER REVIEW

Articles published in The Journal of Aging and Social Change are peer

reviewed using a two-way anonymous peer review model. Reviewers

are active participants of the Aging and Social Change Research

Network or a thematically related Research Network. The publisher,

editors, reviewers, and authors all agree upon the following standards

of expected ethical behavior, which are based on the Committee on

Publication Ethics (COPE) Core Practices. More information can be

found at: https://agingandsociety.com/journal/model.

ARTICLE SUBMISSION

The Journal of Aging and Social Change

publishes quarterly (March, June, September, December).

To find out more about the submission process, please visit

https://agingandsociety.com/journal/call-for-articles.

ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING

For a full list of databases in which this journal is indexed, please visit

https://agingandsociety.com/journal.

RESEARCH NETWORK MEMBERSHIP

Authors in The Journal of Aging and Social Change

are members of the Aging and Social Change Research Network or a

thematically related Research Network. Members receive access to

journal content. To find out more, visit

https://agingandsociety.com/about/become-a-member.

SUBSCRIPTIONS

The Journal of Aging and Social Change is available in electronic and

print formats. Subscribe to gain access to content from the current year

and the entire backlist. Contact us at cgscholar.com/cg_support.

ORDERING

Single articles and issues are available from the journal bookstore at

https://cgscholar.com/bookstore.

HYBRID OPEN ACCESS

The Journal of Aging and Social Change is Hybrid Open Access,

meaning authors can choose to make their articles open access. This

allows their work to reach an even wider audience, broadening the

dissemination of their research. To find out more, please visit

https://agingandsociety.com/journal/hybrid-open-access.

DISCLAIMER

The authors, editors, and publisher will not accept any legal

responsibility for any errors or omissions that may have been made in

this publication. The publisher makes no warranty, express or implied,

with respect to the material contained herein.

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

The Journal of Aging and Social Change

Volume 10, Issue 2, 2020, https://agingandsocialchange.com

© Common Ground Research Networks, Angela Kydd, Anne Fleming, Isabella Paoletti,

Simona Hvalič-Touzery, All Rights Reserved. Permissions: cgscholar.com/cg_support

ISSN: 2576-5310 (Print), ISSN: 2576-5329 (Online)

https://doi.org/10.18848/2576-5310/CGP/v10i02/53-73 (Article)

Exploring Terms Used for the

Oldest Old in the Gerontological Literature

Angela Kydd,

1

Robert Gordon University, UK

Anne Fleming, Independent Researcher, UK

Isabella Paoletti, Social Research and Intervention Centre (CRIS), Italy

Simona Hvalič-Touzery, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Abstract: Background: In response to the global increasing age of the population, there is general agreement on the need

to define what is meant by “old.” Yet there is no consensus on age groups within the definition of old, which makes

comparative studies of people of differing ages in advancing years impossible. Attempts to sub-categorize the “old” also

show little consensus. This article serves to open a dialogue, as an illustrative example of these inconsistencies. Aim: To

examine definitions of the “oldest old” and “fourth age” in order to highlight such inconsistencies and the need for

consistent age stratifications. Method: The authors conducted a literature search from January 2003 to April 2015 using

the six top-most-rated non-medical journals in gerontology and again in 2018–2019 to give currency to the article.

Results: Forty-nine articles in total were reviewed. The findings show little consensus on the age stratifications used to

define the “oldest old” and “fourth age,” which ranged from seventy-five plus to ninety-two plus years. Conclusion:

Dividing the “old” population into the oldest old and/or fourth age still shows a lack of consensus, with some authors

suggesting that such divisions have only served to move ageism into very old age. Recommendation: There are terms for

ten-year cohorts, which if universally used, will mean that comparative ageing studies are possible, which in turn will

inform international and national strategy documents, policy initiatives, clinical guidelines, and service provision design.

Implications for Practice: Given the growth in the numbers of people classed as old and the time span being “old”

covers, there is a real need for consensus. Definite age groupings that define people as cohorts, with existing and agreed

words—such as sexagenarians (60–69,) septuagenarians (70–79), octogenarians (80–89), etc., will completely remove

the need for the value-laden term “old” (and all its derivatives) for this poorly defined population.

Keywords: Oldest-old, Fourth Age, 85+, 85 Plus, Age Stratification, Ageism

Introduction

his article aims to add to the dialogue on the term “old” by providing a pilot review, as an

exemplar, to explore empirically how people aged over 80 years are termed and defined in

a limited selection of the gerontological literature. It argues for the use of age cohorts in

decades, which would serve to negate the use of such terms “old,” “older people,” “oldest old,”

and “fourth age,” to name but a few. Such terms not only have ageist connotations, which will be

addressed below, but give no consensus for academics, researchers, policy makers, and educators

to work on. The lack of consensus is apparent in papers and policies regardless of discipline or

country. Such inconsistencies make comparative research on the “old,” and even sub-categories

of the term old, impossible. This article gives reasons why cohort classifications (such as

septuagenarians, octogenarians, etc.) will not only help to ameliorate the negative imagery that

accompanies the scarcely meaningful term “oldest old” but serve to appreciate that research

involving people needs to acknowledge the individual’s cohort and the role their society ascribes

to them at the age

they are, a

long with their environment and culture. As Woods (1996, 4) states

“the older person cannot be studied in isolation from their context: they are enmeshed in a

presumptive world order, rich in accumulated expectancies.”

There is some ag

reement in the literature that old age begins at the age of 60 or 65, due in

part to the age at which women and men retire from the workforce, so old age was commonly

1

Corresponding Author: Angela Kydd, Robert Gordon University and NHS Grampian. School of Nursing and

Midwifery, Garthdee Campus, Aberdeen, AB10 7QG, Scotland, UK. email: a.kydd@rgu.ac.uk

T

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

determined with retirement as a measure.

Yet globally, people are living many years longer

following their retirement and, as a response to this, retirement ages are increasing and these ages

differ between countries. Therefore, defining old age as starting at retirement is ever more

problematic. Attempts to sub-categorize those classed as old into such terms as the “oldest old”

and “fourth age” (terms usually ascribed to those aged 80+) again imply a shared understanding.

However, the age bands used to define these terms vary greatly.

This article presents an exploratory discourse on the lack of consensus and shared

understanding on the nature of the “oldest old” and the “fourth age” and suggests that people

should be referred to by their age cohort. This study supports earlier work by Serra et al. (2011)

who suggest that cohort age classifications would dispel the ageist imagery that comes with

defining the “old.” It also responds to the call by Sabharwal et al. (2015) who recommend that

popular definitions of “old people” should be uniform and agreed. They point out that research

on the “elderly” cover ages of 50 and over, usually broken into disparate age bands, thus making

research clinically irrelevant on this population.

Background

The term “older people” is seen by many researchers as a crude and unhelpful categorization of

mature and ageing people. In the 1970s, Neugarten (1974) put forward the concept that older

people are not one homogeneous group and that age stratification would serve to delineate

between the characteristics of the fit old and the needy old. She suggested the “young old”

(55–75), those who were retired but healthy, affluent, and politically active, and the “old old”

(over 75), those who might need supportive services to function as fully as possible. These age

bands gave no consideration to factors that affect people as they age, such as culture,

socioeconomic status, health status, or environment. Yet, they did serve to acknowledge that

classifying people as old, from the age of 60 to potentially the age of 110, was far too broad to

have any meaning. Similarly, the concept of the “Third Age” and “Fourth Age” is associated

with Laslett (1994), who sought to dispel marginalization of the old. Laslett (1994) argued that

following retirement, the “old” were an active group of economic importance. This concept

addressed the

negative imagery (

ageism) of the retired person but introduced the concept of the

fourth age, where dependency represented a key marker in the transition from third to fourth age.

The development of ideas about later life serve to emphasize autonomy, agency, and self-

actualization but also serve to distinguish the concept of the fourth age, where dependency

represents a key marker in the transition. Komp (2011) concurs with Laslett’s work, that the

fourth agers are distinct from “third agers.” The third agers are healthy retirees who contribute to

the economy, whilst the fourth agers are retirees in poor health—those who fit the stereotype of

“old people.” Again, this is not particularly helpful for ageing studies because age alone does not

determine health status or economic contribution. In essence, dividing groups by economic

contribution has served to move ageism into very old age, in that old people are viewed as

unproductive and a drain on health and social care resources. Arguments against such categories

of old have been put forward by George (2011), who suggests that in creating a third and fourth

age division, a more severe form of ageism

is created fo

r those in the fourth age. She states, “just

as the image of the Third Age is socially desirable because it is not old age, the image of a Fourth

Age is socially undesirable because it reinforces negative stereotypes of later life. Fourth Agers

will be viewed as frail, dependent, lonely, sick and as coping with impending death” (George

2011, 253). This sentiment is backed by Gilleard and Higgs (2015), who describe the fourth age

as absorbing all the negative aspects of the aging process by exaggerating a gap between the fit

and the frail, creating a fear for those who see themselves as transitioning from their third to

fourth age (Kydd et al. 2018).This supports earlier work by Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn (2008), who

used longitudinal data from the Berlin Ageing Study over six years and found that people

generally felt around thirteen years younger than their chronological age until they experienced

illness or social loneliness due to the illness(es) or the loss of a significant other. Such losses lead

54

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

individuals to perceive themselves to be old as per Neugarten’s (1974) stages or Laslett’s (1994)

fourth age.

North and Fiske (2013) criticize ageism research for considering the over 65s as a

homogeneous group. They recommend that ageism studies should focus on the subgroupings of

“young-old” and “old-old” as described by Neugarten (1974). This, they state, would lead to a

better understanding of the unique prejudices encountered by sub-categories. They further state

that grouping everyone over a certain age as old is an antiquated definition that will become even

more so with anticipated increasing longevity.

These discourses make important distinctions but do little to provide consensus on what is

meant by the terms “older people,” “oldest old,” and “fourth age.” Yet age stratifications have

been adopted in policy documents and today, the vast majority of ageing studies and policy

documents use age bands to define an “old” population (Baars 2007). Yet again, there is no

uniformity to the age stratifications used and this can be seen in five such examples: WHO

(2015) report on the over 60s, 70s, and 80s as does Age International (2015) and Eurostat

(Eurostat 2019a), while the United Nations (2015) indicate the old (over 65) and the oldest old

(over 85), and the Association of Directors of Public Health (2018) refer to people aged 65–74

and the over 75-year-olds. Thus the literature and policy documents on “older people,” “later

life,” and “oldest-old” use different age stratifications and terminologies, which makes such

classifications meaningless (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2013).

In Japan, there have been moves to reach a national agreement on what constitutes old and

oldest old. The rationale for redefining the term “elderly” in Japan was the growing numbers of

people younger than 75 who were robust and active. A cross sectional study on the physical and

psychological health of older people in Japan found a phenomenon of “rejuvenation,” where the

traits of ageing were found to have been delayed by five to ten years. This Japanese study

informed the work of the Japan Gerontological Society and the Japan Geriatrics Society to

reconsider the definition of older people (Ouchi et al. 2017). After three years’ work, the

committee proposed the following classification: 65 to 74 years (pre-old age), 75 and over (old

age), and 90 and over (oldest-old or super-old). The authors conclude that the two main aims of

redefining “elderly” were to motivate those aged 60–74 to continue to be active and valued

contributors to society and to create a super-aged population in a positive way. This approach to

categories will be useful for ageing studies, but still comes with an implicit trajectory of

becoming disabled.

Follow-up wor

k will be interesting to see if those who transition from the old

age category will view themselves in a positive way when classed as the oldest old/ super old at

90.

Chronological age is

a fact but the effects of ageing are diverse and unique. In gaining

consensus as to who “older people” are, it appears that the problem lies between the concepts of

biological age and chronological age. Baars (2010) refers to three dimensions of ageing: (1)

natural (physical and biological), (2) socio-cultural, and (3) personal. This acknowledges that

ageing is not a regular process. Chronological age does not predict bodily decline. Moreover, as

Baars (2010, 10) points out “all human aging takes place in specific contexts which co-constitute

its outcomes,” which means that by having an agreement on using cohort age bands it will then

be possible to compare and contrast how different cohorts age, with consideration to the

dimensions of ageing.

Agreement has to be reached. The growing numbers of people aged over 60 and the

booming numbers of people aged over 80 illustrate that age cohorts need to be considered as

acceptable ways in which to refer to “older people.” According to Eurostat data (Eurostat 2019a),

28.6 million people aged 80 and over were living in the European Union (EU-28) in 2018, 6.6

million more than ten years ago. The growing share of older people in the EU-28 (from 4.4% in

2008 to 5.6% in 2018) illustrates that in 2018, one in every eighteen people living in the EU were

aged 80 and over. This increase was seen in all Member States, except Sweden (Eurostat 2019b).

55

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

These numbers, although important in terms of understanding demographic trends, do not

reflect the heterogeneity of the older population. It is widely understood that differences among

people of the same age may be greater than those attributed to chronological age differences. A

growing body of research indicates that a person’s ageing is influenced by multiple factors such

as genetics, socioeconomic factors, and environmental factors (Lowsky et al. 2014; Mitnitski,

Howlett, and Rockwood 2017; Yashin et al. 2016; Andrew 2015). People in specific age cohorts

aged 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, and 110 all share a historical context and sub groups within these

cohorts will share certain commonalities such as socioeconomic status and cultural status within

that context. Thus, referring to sexagenarians (60–69) and septuagenarians (70–79), and so on,

provides a common understanding of who are actually being researched.

A study on the use of the term “older people” (and if possible, the definitive ages ascribed)

would be too large to undertake for an unfunded pilot study. Studies discussing (as opposed to

using) the definitions of the terms “oldest old” and “fourth age” are relatively scarce (Gilleard

and Higgs 2013, 2015). So the authors undertook a pilot study to empirically review how the

terms “oldest old” and “fourth age” are articulated in the relevant gerontological literature; thus

the articles were used as data. The aim is to illustrate the uselessness of the term “older people”

and the lack of consensus in determining the contemporary differing terms used for the “oldest

old” and “fourth age.”

Method

The methodological approach of this study is not a conceptual analysis of the term “oldest old”;

the authors’ approach is empirical and serves as a pilot study. This study examines the language

use of the terms “fourth age” and “oldest old” in a specific scientific community—researchers in

gerontology. Gerontological articles were used as data and a sociolinguistic approach was

adopted (Wodak, Johnstone, and Kerswill 2011). This pilot study examined the use of the terms

“fourth age” and “oldest old” (which will yield corresponding terms) in relation to age grouping,

in six top-rated journals in gerontology (Guerrero-Bote and Moya-Anegón 2012). These journals,

with their impact factors from 2015 are: Age and Aging (4.282), The Gerontologist (3.505), The

Journals of Gerontology B (3.064), Aging & Mental Health (2.658), Ageing & Society (1.386),

Research on Ageing (1.214). Whilst aware that there are many other journals in gerontology and

many articles on old age that are included in non-gerontological specific journals, the decision

was made that these journals represented an appropriate starting point for inquiry, being the most

read and most quoted journals among researchers in the field of

gerontology. The si

x journals

were accessed on line and examined from years 2003 to 2015. There were no specific reasons for

choosing this particular time span; a different one could have been chosen to test language use

for this pilot study; it is a significantly long period of time (thirteen years) but manageable within

the scope of an initial research. The rationale for the search was to highlight how the term old is

poorly defined and yet used to describe and cater for populations as if a shared understanding

exists. The search terms used were to seek consensus of subcategories of old, namely the “oldest

old” and “fourth age.”

In order to provide currency to this article, which took several years to complete, a second

recent search was conducted. To provide consistency, the same journals and search terms were

used. However, the time limit specified was for the period January 2018 to March 2019.

Keywords and Inclusion Criteria

The authors’ search strategy involved accessing the chosen journals’ websites, and inserting the

keywords “fourth age” and “oldest old” in the searching quadrant. All terms were searched as

phrases within quotation marks to avoid meaningless returns. The inclusion criteria for the

original search were articles published between 2003 and 2015, full text articles, and written in

English. The follow-up search (January 2018 to March 2019) involved the same strategy. The

56

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

exclusion criteria evolved as the screening procedure developed. Justification for this is

documented throughout the three levels of screening detailed below.

Screening Procedure (1)

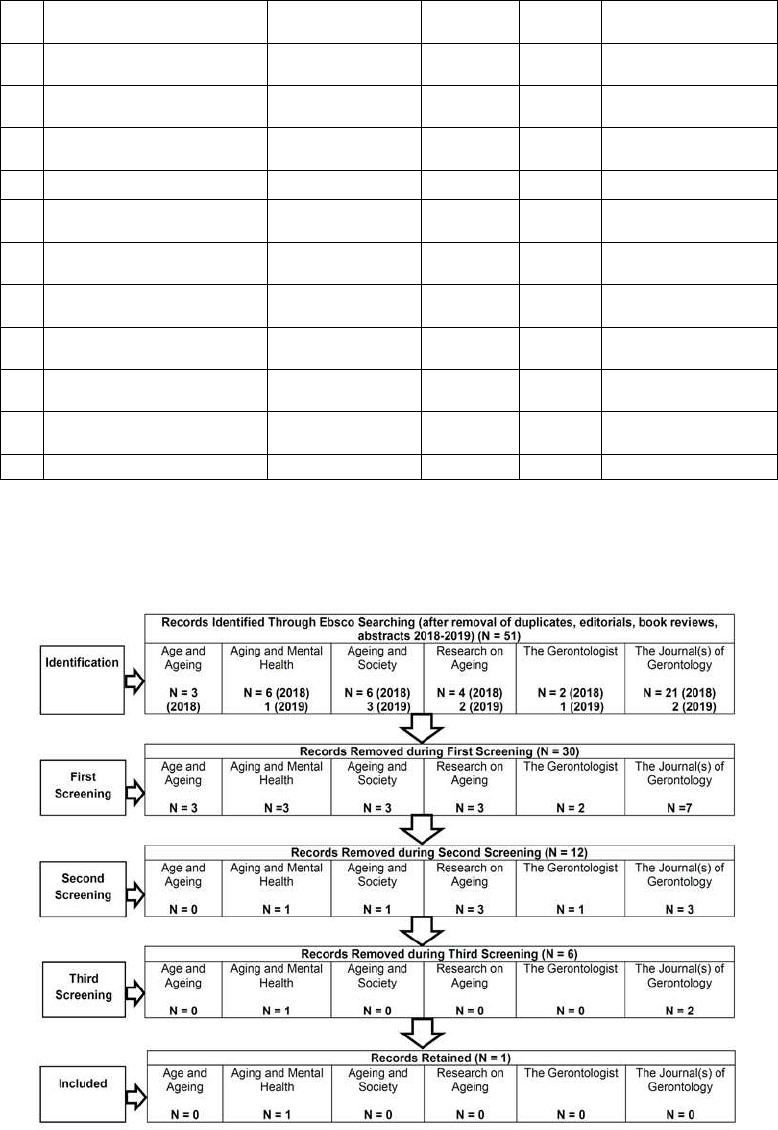

The 2003–2015 search using the keywords yielded the following results: Age and Ageing 131;

Ageing & Mental Health 61; Aging & Society 56; Research on Aging 73; The Gerontologist 117;

The Journals of Gerontology 163; giving a total of 601 articles (see Figure 1 for a breakdown of

the screening process and findings). The 2018–2019 yielded fifty-one articles (see Figure 2): Age

and Ageing 3; Ageing and Mental Health 7; Aging & Society 9; Research on Aging 6; The

Gerontologist 3; The Journals of Gerontology 23.

Prior to independent screening by the authors, exclusion criteria were developed to refine the

search results to provide a greater focus on the use of the terms “fourth age” and “oldest old.”

These were topics related to specific health conditions; older people undergoing treatment for a

clinically diagnosed physical illness (e.g., cancer) or mental illness (e.g., dementia or

depression); assessments for long-term continuing care; community interventions to improve the

physical and social environment that are not directly targeted at people over 65 or their carers;

interventions tailored to those in acute or palliative care; medical or surgical interventions; pre-

retirement financial planning schemes; specific therapeutic interventions for diagnosed mental

health disorders covered by National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines, such as

reminiscence therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. The results were then discussed and

agreed, which resulted in the rejection of 266 articles in the first part of this study (2003–2015)

and thirty rejections for the updated part (2018–2019).

Screening Procedure (2)

Further exclusion criteria were developed as the authors became familiar with the literature, and

these were then used for a joint second screening. This included articles that gave no useful age

stratification when discussing old and oldest old studies; articles that compared “younger,”

“middle aged,” and “older” people; articles that used a mean age; articles that used purely over

age 50; articles that gave no rationale for an unusual age bracket; articles referring solely to

“older adults.” Following this second screening, a further 102 papers were rejected from the

2003–2015 search, leaving 233 papers for review; and in the 2018–2019 search, twelve were

rejected leaving nine papers for review.

Screening Procedure (3)

Due to the volume of papers, a third screening was undertaken to narrow the focus further. With

the aims of the article in mind, the authors decided to acknowledge but exclude the many

longitudinal studies that segregated the ages of the old, but did not add to the discourse

surrounding the divisions between the third and fourth ages, or old and oldest old. Longitudinal

studies can use any age parameters selected from the datasets. However, because these studies

selected participants aged 80, 85, 90, and 100 (illustrating the lack of consensus on the “oldest

old”), the authors agreed to reject these. Such studies included Leiden 85-plus Study (Caljouw et

al. 2013), The OCTO-Twin Study (Hassing et al. 2004), and The Georgia Centenarian Study

(Cho et al. 2015). Further exclusions were studies that focused on single issues that did not add to

the discourse on the fourth age and the oldest old. Therefore, the third screening had the

following exclusion criteria: longitudinal studies; veteran studies; and, studies focused on

dementia and depression. This resulted in 185 papers being excluded and a manageable forty-

eight retained for examination (see Figure 1).

57

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Figure 1: Flow Diagram of Article Selection 2003–2015

Source: Kydd et al. 2020

Out of the selected forty-eight studies, nine were observational studies, twenty-four

quantitative, five qualitative studies, four register-based studies, two expert opinions, one mixed-

methods, one a systematic review of the cohort studies, one experimental, and one ethnographic

study. Half (n = 24) of the studies were conducted in European countries and eighteen in North

America. The remaining studies were carried out in Asia (n = 4) and Malaysia (n = 1). Six

studies were conducted in partnership between countries in different regions (see Table 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of the Reviewed Articles

No Author/Year Study Type N

Age in

Sample

Country. Discipline

1.

Beel-Bates, Ingersoll-

Dayton, and Nelson 2007

Qualitative 31 85+ USA. Social Work

2. Berg et al. 2006 Quantitative 315 80–98

Sweden/ USA.

Psychology

3. Birditt 2014 Quantitative 110 40-95 USA. Psychology

4.

Birditt and Fingerman 2003

Quantitative

185

13-99

USA. Psychology

5. Bowling and Grundy 2009

Observational -

Cross-sectional

1.384 85+

United Kingdom.

Social Science

6. Bowling et al 2005 Quantitative 533 65+

United Kingdom.

Social Science

7. Boyes 2013 Mixed methods 80

63-80 /

54-83

New Zealand.

Education

8. Braungart et al. 2007

Observational

cohort

149

86, 90,

84

USA/ Sweden.

Psychology

9.

Bronnum-Hansen et al.

2009

Observational

cohort

2.258 92-100

Denmark.

Public Health

10. Chipperfield 2008 Quantitative 198 80-98

USA/Canada

Psychology

58

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

11. Cicirelli 2006 Quantitative 192 60-84 USA. Psychology

12. Conroy et al. 2014

Observational

cohort

7.5 85+

United Kingdom.

Medicine

13. Cotter et al 2009

Observational

cohort

250 65+

Ireland.

Medicine

14. Duncan 2008 Opinion

United Kingdom.

Medicine

15.

Engelter, Bonati, and Lyrer

2006

Systematic

review of cohort

studies

6 studies

(n=2,244)

80+

Switzerland.

Medicine

16. Erlangsen et al 2004 Register-based 2.505 50+

Germany/Denmark.

Sociology

17. Fastame et al. 2013 Quantitative 96 85+

Italy.

Psychology

18. Fastamea and Penna 2014 Quantitative 94 75-99

Italy.

Psychology

19. Gott et al 2006 Quantitative 542 60+

United Kingdom.

Nursing

20. Gunnarsson 2009 Qualitative 20 75-90

Sweden.

Social Work

21. Hildon et al. 2010 Quantitative 174 68-82

United Kingdom.

Psychology

22.

Hutnik, Smith, and Koch

2012

Qualitative 16 100+

United Kingdom.

Psychology

23. Jeon and Dunkle 2009

Observational

cohort

193 85+

Korea/USA.

Social Work

24.

Jopp, Rott and Oswald

2008

Quantitative 356 65-94

USA/Germany.

Psychology

25.

Klenk, Becker, and Rapp

2010

Register-based

65+

Germany.

Medical Engineering

26. Korhonen et al. 2012 Register-based

80+

Finland.

Medicine

27. Krause 2004 Quantitative 1.518 65+

USA.

Sociology

28.

Lang, Baltes, and Wagner

2007

Quantitative 1.125 20-90

Germany.

Psychology.

29. Larrson 2006 Quantitative

2 studies

(n=6,737)

65-99

Sweden.

Social Work

30. Lee and Dunkle 2010 Quantitative 213 85-94

South Korea/USA.

Social Work

31. Liang 2014 Quantitative 860 85+

China.

Social Work

32. Lloyd et al. 2014 Quantitative 34 70+

United Kingdom.

Social Gerontology

33. MacDonald et al. 2009 Quantitative 230 100+

USA.

Economics

34.

Mast, Azar, and Murrell

2005

Quantitative 2.916 50+

USA.

Psychology

35. McGinnis 2009 Experimental 137 17-85

USA.

Psychology

36. Moe et al. 2012 Quantitative 120 80-101

Norway/Sweden.

Nursing

37. Momtaz et al. 2011 Quantitative 1.415 60-100

Malaysia.

Gerontology

59

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

38.

Muramatsu and Akiyama

2011

Expert opinion

USA.

Gerontology

39. Nesset al. 2005 Quantitative 1.099 52+

USA.

Medicine

40. Oswald et al. 2010 Quantitative 381 65-94

Germany/ USA.

Psychology

41.

Quentiart and Charpentier

2012

Qualitative 25 65+

Canada.

Sociology

42. Roth et al. 2012 Ethnographic 47

USA. Sociology

43. Thygesen et al. 2009 Quantitative 214 75+

Norway.

Health Science

44. Wastesson et al. 2012 Register-based 3.447 100+

Sweden.

Medicine

45.

Windsor, Burns, and Byles

2011

Quantitative 552 55-74

Australia/ USA.

Psychology

46. Weyerer et al. 2013

Observational

cohort

3.214 75+

Germany.

Psychology

47. Xie et al. 2008

Observational

cohort

982 90+

United Kingdom.

Biostatistics

48. Zimmer 2005

Observational

cohort

7.594 80-105

China.

Sociology

n

48

Source: Kydd et al. 2020

Figure 2 shows the 2018–2019 search rejected six articles, leaving three for review, only one of

which was retained for this study. This article is reported on in the discussion. The updated

search was to add a currency to the article, but the main focus of this article was to look at the

2003–2015 time period.

Figure 2: Flow Diagram of Article Selection 2018-2019

Source: Kydd et al. 2020

60

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

Results from the Analysis of Data (2003–2015)

The detailed results are presented analyzing the forty-eight articles selected that met the strict

inclusion criteria. Within each article it was interesting to see the differences in the actual ages

ascribed to those classed as “oldest old” and those classed as “fourth age”. Consensual categories

included octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians. Further differences were found in some

articles in relation to (i) the discourses on the oldest old and fourth age groups, (ii) the various

terms and their use describing the oldest old and fourth age, and (iii) the various age

stratifications used to define oldest old and fourth age. These differences are reported in Table 2.

Table 2: Discourses on Terminology and the Oldest Old Age Definitions Found in the Articles

Terminology

Oldest old age definition

No.

Fourth

age

Very elderly/

very old/ very

old adults/

very old

individuals/

very old age

group

Oldest old

/ oldest

old adults

Older age

group / Old-

old / Older

adults with

advancing

age

Octo/

Nona/

Cent/

Extreme

1

75+ 80+ 85+ 90+

90-

100

100

+

1.

x

x

2.

x

x

3.

x

x

4.

x

x

5.

x

x

6.

x

x

7.

x

8.

x

x

9.

x x

x

10.

x

x

x

11.

x

x

12.

x

x

13.

x

x

14.

x

15.

x

x

16.

x

x

x

17.

x x

x

18.

x

x

19.

x

x

20.

x

x

x

21.

x

22.

x

x

23.

x x

x

24.

x x x x

x

25.

x

x

61

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

26.

x

x

27.

x x

x

28.

x

x

29.

x

x

30.

x

x

31.

x

x

32.

x

x

33.

x

x

34.

x

x

35.

36.

x

x

37.

x

x

38.

x

x

39.

x

x

40.

x x

x

41.

x

x

42.

x

x

43.

x

44.

x

x

45.

46.

x

x

47.

x x

x

48.

x

x

n

4 12 31 7 3 3 11 18 4 1 5

Legend:

1

Octo: Octogenarians, Nona: Nonagenarians, Cent: Centenarians, Extreme: Extreme Old Age

Source: Kydd et al. 2020

The results highlight the point that “old age” studies have little consensus on what age constitutes

the “oldest old” or “fourth age.” In searching for these terms in a limited selection of articles,

many other derivative terms used to describe “older people” were found. As stated above, these

are reported upon as (i) the discourses on the oldest old and fourth age groups, (ii) the various

terms and their use describing the oldest old and fourth age, and (iii) the various age

stratifications used to define oldest old and fourth age.

Discourses on the Oldest Old and Fourth Age Groups

In the articles examined, the oldest old and fourth age can be found as commencing at 75 and

over, 80 and over, 85 and over, or 90 and over. In three papers, the “oldest old” were classed as

under 80 years of age (Gunnarsson 2009; Lloyd et al. 2014; Fastame and Penna 2014). Lloyd et

al. (2014) referred to people aged 75 and over as being in the “fourth age.” Similarly,

Gunnarsson (2009) referred to those aged 75 and over as being in the “fourth age,” “the oldest

old,” and the “frail elderly.” Fastame and Penna (2014) initially defined the “oldest old” as 85

and over, but then described the 75 and over age group as the “oldest old.”

Eleven papers d

efined the 80 and over age group as the “very-old,” “oldest-old,” “oldest old

adulthood,” and “very elderly” (Birditt 2014; Birditt and Fingerman 2003; Engelter, Bonati, and

Lyrer 2006; Erlangsen et al. 2004; Moe et al. 2013; Oswald et al. 2011; Zimmer 2005; Jopp,

62

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

Rott, and Oswald 2008; Chipperfield 2008; Berg et al. 2006; Larsson 2006). Erlangsen et al.

(2004) implied that 80 and over defined the “oldest old.” Zimmer (2005) and Engelter et al.

(2006) define the “oldest old” as 80 and over but with no rationale. Other authors, however,

provided clear age stratifications and gave the definition of the “oldest old” as 80 and over.

The most f

requent chronological definition of the oldest old was “85 and over,” which was

used in just over a third of the papers (n = 18) (Beel-Bates, Ingersoll-Dayton, and Nelson 2007;

Bowling and Grundy 2009; Braungart Fauth et al. 2007; Cicirelli 2006; Conroy et al. 2014;

Fastame et al. 2013; Gott et al. 2006; Jeon and Dunkle 2009; Krause 2004; Lee and Dunkle 2010;

Liang 2014; Mast, Azar, and Murrell 2005; Momtaz et al. 2011; Ness et al. 2005; Quéniart and

Charpentier 2012; Weyerer et al. 2013; Bowling et al. 2005). Six of these papers (Beel-Bates,

Ingersoll-Dayton, and Nelson 2007; Fastame et al. 2013; Gott et al. 2006; Lee and Dunkle 2010;

Weyerer et al. 2013; Bowling et al. 2005) clearly defined the “oldest old” as those aged 85 years

and over with reference to the literature. Six papers defined the “oldest old” as those aged 85 and

over, but did not provide a rationale for selecting this age (Beel-Bates, Ingersoll-Dayton, and

Nelson 2007; Bowling and Grundy 2009; Fastame et al. 2013; Gott et al. 2006; Jeon and Dunkle

2009; Weyerer et al. 2013). Cicirelli (2006) inferred

that tho

se aged 85 and over must be the

“oldest old,” as did Conroy et al. (2014) who stated that the 85 and over age group were those

who were identified in local data to have the highest incidence of health care usage. However,

the demographics of the local data were not referred to. Weyerer et al. (2013) talked of the

“oldest old” as 85 and over, but only once in the key points and later in the paper referred to

those aged 75 and over as the “older old.”

Four papers s

poke of those aged 90 and over. Bronnun-Hansen et al. (2009) using the term

“oldest old” only in the title of their paper, but they did cite two references to support using the

term “very old” when referring to people aged 90 and over. The remaining three papers referred

to age 90 and over as the “oldest old” but provided no rationale (Korhonen et al. 2012; Klenk,

Becker, and Rapp 2010; Xie et al. 2008).

Two articles referred to centenarians, with the term “extreme old age” (Hutnik, Smith, and

Koch 2012; MacDonald et al. 2009) and MacDonald et al. (2009) added the term “near-

centenarians.” Lang et al. (2007) referred to the 90-100 year olds as “very old people,” whereas

Wastesson et al. (2012) simply referred to octogenarians, nonagenarians, and centenarians

The Various Terms and Their Use Describing the Oldest Old and Fourth Age

The authors found not only different age groups for the “oldest old” and “fourth age,” but also

variations in the terminology itself. The most frequent term used was “the oldest old” (n = 31),

followed by “the very old” (n = 12) and the “fourth age”(n = 4). Several variations of the “the

very old” were used, such as “very elderly,” “very old adults,” “very old age group,” “very old

age,” “very old elders,” “very old individuals,” “very old people,” and “very old persons”

(Bowling and Grundy 2009; Gott et al. 2006; Jeon and Dunkle 2009; Krause 2004; Erlangsen et

al. 2004; Moe et al. 2013; Oswald et al. 2011; Bronnum-Hansen et al. 2009; Xie et al. 2008;

Lang, Baltes, and Wagner 2007; Jopp, Rott, and Oswald 2008; Chipperfield 2008). Birditt and

Fingerman (2003) spoke of “the oldest old adulthood,” which served to show how diverse the

sub-categories of “oldest old and “fourth age” have become.

Differences in the u

se of terms were found not only between the papers but also within the

papers. The terminology varied in ten papers, including “very old,” “oldest old,” “very old

adults/elders/group/individuals/people,” “elder individuals,” “fourth age,” “frail elderly” and “the

very oldest age” (Fastame et al. 2013; Jeon and Dunkle 2009; Krause 2004; Erlangsen et al.

2004; Oswald et al. 2011; Gunnarsson 2009; Bronnum-Hansen et al. 2009; Xie et al. 2008; Jopp,

Rott, and Oswald 2008; Chipperfield 2008). For example, Bronnun-Hansen et al. (2009) used the

term “oldest old” only in the title of their paper, but later in the paper used the terms “very old,”

“elder individuals,” “very old individuals,” and then “nonagenarians” when referring to people in

their nineties.

63

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

The American s

tudies quite consistently used the term “the oldest old” (Beel-Bates,

Ingersoll-Dayton, and Nelson 2007; Braungart Fauth et al. 2007; Lee and Dunkle 2010; Mast,

Azar, and Murrell 2005; Ness et al. 2005; Birditt 2014; Birditt and Fingerman 2003; Lloyd et al.

2014; Berg et al. 2006; Muramatsu and Akiyama 2011). Articles written in partnership between

American and German (Oswald et al. 2011) and American and Canadian researchers

(Chipperfield 2008) used the term “very old.” One American paper also used the term “fourth

age” (Roth et al. 2012). British research used a variety of terms: “fourth age” (Gilleard and Higgs

2013; Lloyd et al. 2014; Duncan 2008); “oldest old” (Bowling et al. 2005; Xie et al. 2008); “very

elderly” (Bowling and Grundy 2009); and “very old” (Xie et al. 2008; Gott et al. 2006). One

British, one American, and one Swedish study used the term “centenarians,” due to the nature of

the studies focusing on people around 100 years and older (Hutnik, Smith, and Koch 2012;

MacDonald et al. 2009; Wastesson et al. 2012). Other articles from European research (Danish,

Irish, Swiss, Italian,

German, Swedish,

Finnish, Norwegian) used a variety of terms, most

frequently the “oldest old” (Fastame et al. 2013; Weyerer et al. 2013; Fastame and Penna 2014;

Korhonen et al. 2012; Klenk, Becker, and Rapp 2010). Other terms used were the “very old”

(Fastame and Penna 2014; Lang, Baltes, and Wagner 2007); those aged “85 years or more”

(Windsor, Burns, and Byles 2013); the “very elderly” (Moe et al. 2013); “fourth age” (Fastame

and Penna 2014); and “older age group” (McGinnis 2009). One study from New Zealand and one

from Israel used the term “fourth age(s)” (Boyes 2013), whilst one article from China and one

from Malaysia used the term “oldest old” (Momtaz et al. 2011; Quéniart and Charpentier 2012).

On close in

spection of the chronological definition of the oldest age group by the region, no

substantial variability in definitions of this age group was found. In addition, the assessment of

chronological definitions of oldest old age by the study type and a discipline did not demonstrate

any substantial differences. The only difference observed was that psychological studies tend to

define more frequently the oldest age group at 80 years of age, while all other disciplines most

frequently defined it at 85 years (Table 3). One of the reasons for no geographical differences

could be the over representativeness of the studies in this sample conducted within developed

counties, although the search terms used were not limited to any geographic region.

Table 3: Demographic Description of the Research in Relation to the

Region, Discipline and Study Type

Median Age Mean Age Range

Standard

Deviation

Variance

Region

Europe (n=20)

85 85 75-100 7.071 50.000

North America (n=12)

85 87 80-100 7.833 61.364

Asia (n=2)

82.5

82.5

80-85

3.536

12.500

Malaysia (n=1)

85

85

85

.

.

North America & Europe

(n=4)

1

85 81.2 80-85 2.500 6.250

North America & Asia

(n=2)

1

85 85. 80-85 0.000 0.000

Discipline

Psychology (n=13)

80 83.1 75-100 5.965 35.577

Social Work (n=6)

85

82.5

75-85

4.183

17.500

Medicine (n=6)

85

87.5

80-100

6.892

47.500

Sociology (n=5)

85 86 80-100 8.216 67.500

Other (n=11)

85 87.7 75-100 7.538 56.818

64

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

Study Type

Quantitative (n=21)

85 82.9 75-100 5.141 26.429

Observational cohort

study (n=8)

85 85.6 80-90 3.204 10.268

Qualitative (n=4)

85

86.2

75-100

10.308

106.250

Register – based (n=4)

90 90 80-100 8.165 66.667

Other (n=4)

92.5 91.2 80-100 10.308 106.250

Legend:

1

The Studies that were Conducted in Cooperation Between Countries in Different Regions

Source: Kydd et al. 2020

The Various Age Stratifications Used to Define Oldest Old and Fourth Age

Further differences in the use of the terms were found in relation to age stratifications. Bowling

and Grundy (2009) referred to 65–85 as “later life and “older age” and those aged 85 and over as

“very elderly”; whereas Conroy et al. (2014) gave age stratifications as 16–64, then 65–74, 75–

84, and then 85 and over. Similarly Mast et al. (2005) used age stratifications of 50–64; 65–74;

75–84; and those age 85 and over, who were defined as the “oldest old.” Momtaz et al. (2011)

used 60–64; 75–84; and 85 and over, again defining those 85 and over as the “oldest old.”

Cicirelli (2006) gave classifications of age as “young old” 60–74 and “mid old” 75–84, with no

mention of what the 85+ population would be called; and McGinnis (2009) used the terms

“young old” and “old old” giving the ages of 67–73 and 80–96, respectively.

Jopp et al. (

2008) defined ages in five-year age bands, starting with 65–69 and ending with

90–94 (65–79 being the young old, and 76–94 being the old old). A further article defined the 80

and over age group as the “old-old” “very old” and “elder individuals” with 65–80 classed as the

“young old” (Oswald et al. 2011), however, clear definitions were given for the distinctions, with

reference to the literature. Ness et al. (2005) gave tables with age bands from 52–64; 65–79 and

then eighty years and over. Fastame and Penna (2014) used the age bands 75–99 years and

Thygesen et al. (2009) used 75 and over to mean “older people,” with no cut off age. Bowling et

al. (2005), Larsson (2006) and Quéniart and Charpentier (2012) all used age stratifications from

the age of 65, with Bowling et al. (2005) referring to the “third age” and the “oldest old.” Lloyd

et al. (2014) referred to people below the age of 75 as being in the “third age,” with those aged

75 and over as

being in t

he “fourth age.” Gunnarsson (2009) referred to the over 75s as the

“fourth age” but does align these terms with a cohort aged 75–90 that she used in her study.

Windsor et al. (2013) described a population-based sample as “midlife” aged 55–59; “young old”

aged 60–74; and “old old” as 75 and over; whereas Birditt and Fingerman (2003), in studying a

group aged 13–99, referred to “adolescents” as 13–16; “young adulthood” 20–29; “middle

adulthood” 40–49; “young old adulthood” 60–69; and “oldest old adulthood” as 80 and over.

Birditt (2014) used these age groups in a later paper, which gave consistency to her work. Lang

et al. (2007) gave age bands of 20–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65–79, and 80 and over, with no rationale,

but they did refer to the 90- to 100-year-olds as “very old people.” Finally, seven articles referred

to “old age,” “very old persons,” “third age,” and “fourth age,” giving differing broad age bands,

or simply using the

term “oldest o

ld” and/or “fourth age” (Bowling et al. 2005; Boyes 2013;

Duncan 2008; Jopp, Rott, and Oswald 2008; Roth et al. 2012; Chipperfield 2008; Muramatsu and

Akiyama 2011). For example, Boyes (2013) used the term “fourth age” in his study, not

indicating a specific age band for the term, but did give specific age bands for his study: 63 to 80

years old and 54 to 83 years old.

65

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Discussion

The ultimate aim of this work is to call for the consistent use of age bands of ten-year cohorts,

with words that have a universal meaning (septuagenarians, octogenarians, etc.). This would

serve to give a dependent variable in ageing research studies and avoid the ageist connotations

bound to the terms “older people” and “fourth age.” Ageist language promotes ageist attitudes,

and such attitudes have concrete consequences in relation to how people over 60 are viewed. So,

in removing negative social constructs about aging and solely referring to factual cohorts,

advanced years can be viewed as a period of personal growth, creativity, and productivity, as

well as a period that can involve losses.

The one article (Etxeberria, Etxebarria, and Urdaneta 2018) sourced from the 2018–2019

search has shown there has been little progression in gaining a consensus of the age of those in

the fourth age or oldest old group. The authors in this selected paper conducted a study (n = 257)

with older people and used age bands 65–74, 75–84, 85–94, and 95–104. They reported on the

over 85s as the “oldest old.” This limited update shows that there is still no consensus on the

terms the “fourth age” or “oldest old”

or indeed those classed as “older people.” In fact, there is a

great variety of terms indicating the “oldest old” or “fourth age” in the articles examined, and

there is no consistency or agreement among the authors on the definitions of the terms, or on the

age bands relating to the terms. These findings also showed no consensus between disciplines or

countries.

Although only a p

ilot study, it is interesting to note that in this review of forty-eight papers,

little influence was found on the use of terms and age definitions by different disciplines. For

example, seventeen articles were sourced from psychology, ranging from 2003 to 2014. These

papers variously used each of the five descriptions of terminology contained in Table 2, and each

of the six oldest old age definitions also described in Table 2. Similarly, six articles from social

work (2006 to 2014) used oldest-old most frequently, but also referred to the “very elderly” and

the “fourth age.” The age bands were used inconsistently, including 85+ years, 80+ years, and

75+ years. Other disciplines (seen in Table 1) included gerontology (3), economics (1),

biostatistics (1), education (1), public health (1), medical engineering (1), social science (2),

medicine (8), sociology (3), nursing (2), health science (1), and social gerontology (1). The

papers reviewed came from fifteen countries and, again, there was no consensus between same

country studies.

Yet for comparative studies and gerontological research, it is important to make a clear

distinction among age groups in old age and equally important to remove the negative

connotations that come with pejorative terms. Context, culture, education, health status,

socioeconomic status, and many other variables dictate how a person ages. Resilience, for

example, is a studied characteristic that can have a relevant impact on the ageing process

(Janssen, Abma, and Van Regenmortel 2012; Zimmermann and Grebe 2014). So, referring to

people 65 years old in the same breath as a person of 98—as in both are called older people—is

problematic. Physiological changes take place as individuals age but each person ages in a

unique manner. Some older people may experience a long and continuous decline of functional

abilities, whereas others may enjoy a long period of health followed by a rapid decline leading to

death. There are of course many other aging trajectories between these two extreme types.

If old a

ge has such variety, then it makes little sense to define the nebulous concept of “older

people” and divide it to create two further nebulous concepts of a third age and fourth age. The

former implies activity and engagement and the latter implies frailty. A 90-year-old person can

be independent and active; a 70-year-old person can be severely disabled.

In the WHO 2017 Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health (World Health

Organization Health Assembly 2017, 10), objective thirteen on combating ageism states, “a key

feature will be to break down arbitrary age-based categorizations (such as labelling those over a

certain age as old). These overlook the great diversity of ability at any given age and can lead to

66

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

simplistic responses based on stereotypes of what that age implies.” As highlighted earlier, the

categories “fourth age” or “oldest old” seem mainly to have moved the negative connotations

into the over 80 age group, which fail to address the WHO call to break down arbitrary age

classifications. It can be argued that at times, differences among individual older people are more

relevant than differences among age cohorts (Baars 2010). Yet, it could also be argued that those

within age cohorts share the same period in time and the same life conditions in specific contexts.

For example, it is now common in Europe that many people aged 65 years old will still be in the

workplace. This fact underlines the relevance of researching cohorts of people in their contexts.

The change in retirement ages has meant that workplaces now need to address issues concerning

an ageing workforce. The point is that the current inconsistences make researching older

populations difficult, a point made by Cohen-Mansfield et al. (2013), who speak of the problem

of comparing cohorts of “older people” due to the inconsistent use of age stratifications by

researchers and policy makers in the field of gerontology.

The authors call for definitive age groupings of 10-year cohorts. These cohorts are already

named and referring to septuagenarians or octogenarians is without bias or prejudice—they are

facts. This provides educators, researchers, and policy makers with a shared understanding of the

groups being referred to. There are a growing number of octogenarians, nonagenarians, and

centenarians that will make up around 20 percent of the European population in 2050. Gaining

consensus regarding studies on ten-year cohort groupings means that studies can be comparable.

For example, older women represent the majority of those aged 85 and over, and they have

generally poorer health conditions than older men of the same age. Yet to build on these findings

with studies that report on the health of people over 70 or 80 or 90 is not possible.

This pilot s

tudy presents certain limitations but also some important points. The study did

not take into account differences in the use of term “oldest old” in relation to: 1) time span: the

ongoing changes in the use of the term in the gerontological field over the thirteen-year period

were not considered; 2) different disciplines: the disciplines of the main authors of the papers

reviewed were noted and demonstrated no agreement among disciplines, but this is purely

anecdotal due to the limited search conducted; 3) different countries and cultures: only partial

differences among countries and culture in the use of the different terms to indicate the “oldest

old” were highlighted as in the different use of the term in American and British articles were

noted. The study was limited to six gerontological journals, and excluded longitudinal studies,

veteran studies and biomedical articles, which the authors acknowledge was very limited. The

sample should be broadened in terms of number of journals included and time span; the sample

should also include articles on old age taken by journals in different disciplines (medicine,

dociology, psychology, etc.). Moreover the articles examined referred mainly to

developed

c

ountries; thus, further research needs to include a broader range of countries.

Overall, the ma

in strength of this study is methodological. It discusses the problem of

terminology using the gerontological literature as data. It suggests an empirical approach in

relation to the issue of terminology. The authors examined articles in the gerontological literature

to look at the actual use of the terms “oldest old” and “fourth age” and found no accordance on

the use of these terms and in relation to the correspondence with age groups.

The authors suggest using age bands that define cohorts. The 60–9 group as sexagenarians,

the 70–79 as septuagenarians, the 80–89 as octogenarians, the 90–99 as nonagenarians, and, of

course, the 100-year-olds as centenarians. Studies would then all be referring to the same age

group, which would facilitate comparison and identifying differences between the different

cohorts, and also differences among individuals within the same cohorts. In applying a factual

chronological age band, potentially pejorative phrases such as “very elderly,” “old old,” “very

old” would no longer be needed.

Perhaps age categories can be useful in defining all populations.

Such categorization would remove the words “young” or “old” from common parlance and serve

to describe cohorts over the life course. These would include denarians (10–19), vicenarians (20–

67

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

29), tricenarians (30–39), quadragenarians (40–49), and quinquagenarians (50–59). These terms

are not in use and were located on medicinenet.com (2017).

Conclusion

In this article, the aim is to raise awareness of the issues concerning defining the oldest old and

the ageist connotation of the term. Variations in age grouping and terminology referring to the

oldest old or fourth age in forty-eight articles in the six top social gerontology journals were

discussed. The findings showed that definitions of oldest old have not been consistently

addressed in the literature. There is, however, agreement that there are no commonalities to be

seen in those aged 60 to 110 years and over, and the authors argue that age stratification is

necessary to break up this 50- to 60-year period of being termed “old.” The different age

groupings used to define the fourth age and the oldest old appear to impinge on researching and

planning services for this population. In using the terms octogenarians, nonagenarians, and

centenarians, there is a clear understanding of the age groups of the populations, without using

the poorly defined and value-laden terms of oldest-old and fourth age.

Funding

The researchers received no funding to conduct this study.

REFERENCES

Age International. 2015. Facing the Facts: The Truth about Ageing. London: Age International.

Andrew, Melissa K. 2015. “Frailty and Social Vulnerability.” Interdisciplinary Topics in

Gerontology and Geriatrics 41: 186–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000381236.

Association of Directors of Public Health. 2018. Policy Position: Healthy Ageing. London:

Association of Directors of Public Health. http://www.adph.org.uk/wp-

content/uploads/2018/05/ADPH-Position-Statement-Healthy-Ageing.pdf.

Baars, Jan 2010. “Time and Aging: Enduring and Emerging Issues.” In International Handbook

of Social Gerontology, edited by D. Dannefer and C. Phillipson, 367–76. New York:

SAGE Publishers.

Baars, Jan. 2007. “Chronological Time and Chronological Age: Problems of Temporal

Diversity.” In Aging and Time: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Jan Baars and

Henk Visser, 1–13. Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing.

Beel-Bates, Cindy A., Berit Ingersoll-Dayton, and Erika Nelson. 2007. “Deference as a Form of

Reciprocity among Residents in Assisted Living.” Research on Aging 29 (6): 626–43.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027507305925.

Berg, Anne Ingeborg, Linda Bjork Hassing, Gerald E. McClearn, and Boo Johansson. 2006.

“What Matters for Life Satisfaction in the Oldest-Old?” Aging & Mental Health 10 (3):

257–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500409435.

Birditt, Kira S. 2014

. “Age Differences in Emotional Reactions to Daily Negative Social

Encounters.” Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social

Sciences 69 (4): 557–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt045.

Birditt, Kira S., and Karen L. Fingerman. 2003. “Age and Gender Differences in Adults”

Descriptions of Emotional Reactions to Interpersonal Problems.” Journals of

Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 58 (4): P237–45.

https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.4.p237.

Bowling, Ann, and Emily Grundy. 2009. “Differentials in Mortality up to 20 Years after Baseline

Interview among Older People in East London and Essex.” Age and Ageing 38 (1): 51–

55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afn220.

68

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

Bowling, Ann, Sharon See-Tai, Shah Ebrahim, Zahava Gabriel, and Priyha Solanki. 2005.

“Attributes of Age-Identity.” Ageing & Society 25 (4): 479–500.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X05003818.

Boyes, Mike. 2013. “Outdoor Adventure and Successful Ageing.” Ageing & Society 33 (4): 644–

65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000165.

Braungart Fauth, Elizabeth, Steven H. Zarit, Bo Malmberg, and Boo Johansson. 2007. “Physical,

Cognitive, and Psychosocial Variables from the Disablement Process Model Predict

Patterns of Independence and the Transition into Disability for the Oldest-Old.”

Gerontologist 47 (5): 613–24.

Bronnum-Hansen, Henrik, Inge Petersen, Bernard Jeune, and Kaare Christensen. 2009. “Lifetime

According to Health Status among the Oldest Olds in Denmark.” Age and Ageing 38

(1): 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afn239.

Caljouw, Monique A. A., Saskia J. M. Kruijdenberg, Anton J. M. de Craen, Herman J. M. Cools,

Wendy P. J. den Elzen, and Jacobijn Gussekloo. 2013. “Clinically Diagnosed Infections

Predict Disability in Activities of Daily Living among the Oldest-Old in the General

Population: The Leiden 85-plus Study.” Age and Ageing 42 (4): 482–88.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft033.

Chipperfield, Judith G. 2008. “Everyday Physical Activity as a Predictor of Late-Life Mortality.”

Gerontologist 48 (3): 349–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/48.3.349.

Cho, Jinmyoung, P

eter Martin, Leonard W. Poon, and Georgia Centenarian Study. 2015.

“Successful Aging and Subjective Well-Being among Oldest-Old Adults.”

Gerontologist 55 (1): 132–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu074.

Cicirelli, Victor G. 2006. “Fear of Death in Mid-Old Age.” Journals of Gerontology. Series B,

Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 61 (2): 75–81.

https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.2.p75.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Dov Shmotkin, Zvia Blumstein, Aviva Shorek, Nitza Eyal, and Haim

Hazan. 2013. “The Old, Old-Old, and the Oldest Old: Continuation or Distinct

Categories? An Examination of the Relationship between Age and Changes in Health,

Function, and Wellbeing.” International Journal of Aging and Human Development,

77(1): 37–57. https://doi.org/10.2190%2FAG.77.1.c.

Conroy, Simon P., Kharwar Ansari, Mark Williams, Emily Laithwaite, Ben Teasdale, Jeremy F.

Dawson, Suzanne Mason, and Jay Banerjee. 2014. “A Controlled Evaluation of

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in the Emergency Department: The “Emergency

Frailty Unit.”” Age and Ageing 43 (1): 109–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/aft087.

Cotter, Paul E., Marion Simon, Colin P. Quinn, and Shaun T O’Keeffe. 2009. “Changing

Attitudes to Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Older People: A 15-year Follow-Up

Study.” Age and Ageing 38: 200–05. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afn291.

Duncan, Colin. 2008.

“The Dangers and Limitations of Equality Agendas as Means for Tackling

Old-Age Prejudice.” Ageing & Society 28 (8): 1133–58.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08007496.

Engelter, Stefan T., Leo H. Bonati, and Philippe A. Lyrer. 2006. “Intravenous Thrombolysis in

Stroke Patients of > or = 80 versus < 80 Years of Age--a Systematic Review across

Cohort Studies.” Age and Ageing 35 (6): 572–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl104.

Erlangsen, Annette, Bernard Jeune, Unni Bille-Brahe, and James W. Vaupel. 2004. “Loss of

Partner and Suicide Risks among Oldest Old: A Population-Based Register Study.” Age

and Ageing 33 (4): 378–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh128.

Etxeberria, Igone, Itziar Etxebarria, and Elena Urdaneta. 2018. “Profiles in Emotional Aging:

Does Age Matter?” Aging & Mental Health 22 (10): 1304–12.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1286450.

Eurostat. 2019a. “Population on 1 January by Age Group and Sex [Demo_pjangroup].” Eurostat.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

69

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

———. 2019b. “Population: Structure Indicators [Demo_pjanind].” Eurostat.

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database.

Fastame, Maria Chiara, Maria Pietronilla Penna, E. S. Rossetti, and M. Agus. 2013. “Perceived

Well-Being and Metacognitive Efficiency in Life Course: A Developmental

Perspective.” Research on Aging 35 (6): 736–49.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027512462411.

Fastame, Maria Chiara, and Maria Pietronilla Penna. 2014. “Psychological Well-Being and

Metacognition in the Fourth Age: An Explorative Study in an Italian Oldest Old

Sample.” Aging & Mental Health 18 (5): 648–52.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.866635.

George, Linda. 2011. “The Third Age: Fact or Fiction - and Does It Matter?” In Gerontology in

the Era of the Third Age: Implications and Next Steps, edited by D. C. Carr and K.

Komp, 245–59. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Gilleard, Chris, and Paul Higgs. 2013. “The Fourth Age and the Concept of a “Social

Imaginary”: A Theoretical Excursus.” Journal of Aging Studies 27 (4): 368–76.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2013.08.004.

Gilleard, Chris, and Paul Higgs. 2015. Rethinking Old Age: Theorizing the Fourth Age. London:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Gott, Merryn, Sarah Barnes, Chris Parker, Sheila Payne, David Seamark, Salah Gariballa, and

Neil Small. 2006. “Predictors of the Quality of Life of Older People with Heart Failure

Recruited from Primary Care.” Age and Ageing 35 (2): 172–77.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afj040.

Guerrero-Bote, V

icente P., and Félix Moya-Anegón. 2012. “A Further Step Forward in

Measuring Journals” Scientific Prestige: The SJR2 Indicator.” Journal of Informetrics 6

(4): 674–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2012.07.001.

Gunnarsson, Evy. 2009. ““I Think I Have Had a Good Life”: The Everyday Lives of Older

Women and Men from a Lifecourse Perspective.” Ageing & Society 29 (1): 33–48.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08007642.

Hildon, Zoe, Scott M. Montgomery, David Blane, Richard D. Wiggins, and Gopalakrishnan

Netuveli. 2010. “Examining Resilience of Quality of Life in the Face of Health-Related

and Psychosocial Adversity at Older Ages: What Is ‘Right’ About the Way We Age?”

Gerontologist 50 (1): 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp067.

Hassing, Linda B., Scott M. Hofer, Sven E. Nilsson, Stig Berg, Nancy L. Pedersen, Gerald

McClearn, and Boo Johansson. 2004. “Comorbid Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and

Hypertension Exacerbates Cognitive Decline: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study.”

Age and Ageing 33 (4): 355–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh100.

Hutnik, Nimmi, Pam Smith, and Tina Koch. 2012. “What Does It Feel like to Be 100? Socio-

Emotional Aspects of Well-Being in the Stories of 16 Centenarians Living in the United

Kingdom.” Aging & Mental Health 16 (7): 811–18.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.684663.

Janssen, Bienke M., Tineke A. Abma, and Tine Van Regenmortel. 2012. “Maintaining Mastery

despite Age Related Losses. The Resilience Narratives of Two Older Women in Need of

Long-Term Community Care.” Journal of Aging Studies, Special Section: Innovative

Approaches to International Comparisons, 26 (3): 343–54.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2012.03.003.

Jeon, Hae-S

ook, and Ruth E. Dunkle. 2009. “Stress and Depression among the Oldest-Old: A

Longitudinal Analysis.” Research on Aging 31 (6): 661–87.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027509343541.

Jopp, Daniela, Christoph Rott, and Frank Oswald. 2008. “Valuation of Life in Old and Very Old

Age: The Role of Sociodemographic, Social, and Health Resources for Positive

Adaptation.” Gerontologist 48 (5): 646–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/48.5.646.

70

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

KYDD ET AL.: EXPLORING TERMS USED FOR THE OLDEST OLD

Klenk, Jochen, Clemens Becker, and Kilian Rapp. 2010. “Heat-Related Mortality in Residents of

Nursing Homes.” Age and Ageing 39 (2): 245–52.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afp248.

Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, Anna, Dana Kotter-Grühn and Jacqui Smith. 2008 “Self Perceptions of

Aging: Do Subjective Age and Satisfaction with Aging Change During Old Age?” The

Journals of Gerontology: Series B 63 (6): 377–85.

https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.6.P377.

Komp, Kathrin. 2011. “The Political Economy of the Third Age.” In Gerontology in the Era of

the Third Age, edited by Dawn Carr and Katherin Komp, 51–66. New York: Springer.

Korhonen, Niina, Seppo Niemi, Mika Palvanen, Jari Parkkari, Harri Sievänen, and Pekka

Kannus. 2012. “Declining Age-Adjusted Incidence of Fall-Induced Injuries among

Elderly Finns.” Age and Ageing 41 (1): 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr137.

Krause, Neal. 2004. “Lifetime Trauma, Emotional Support, and Life Satisfaction among Older

Adults.” The Gerontologist 44 (5): 615–23. https://doi.org/44/5/615 [pii].

Kydd, Angela, Anne Fleming, Sue Gardner, and Patricia Hafford-Letchfield. 2018. “Ageism in

the Third Age.” In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism, edited by Liat Ayalon and

Clemens Tesch-Roemer, 115–30. New York: Springer Open Press.

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-73820-8.pdf.

Lang, Frieder R., Paul B. Baltes, and Gert G. Wagner. 2007. “Desired Lifetime and End-of-Life

Desires across Adulthood from 20 to 90: A Dual-Source Information Model.” Journals

of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 62 (5): 268–76.

https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.5.p268.

Larsson, Kristina. 2006.

“Care Needs and Home-Help Services for Older People in Sweden:

Does Improved Functioning Account for the Reduction in Public Care?” Ageing &

Society 26 (3): 413–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X05004496.

Laslett, Peter. 1994. “The Third Age, the Fourth Age and the Future.” Ageing & Society. 14 (3):

436–47. Htps://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X00001677.

Lee, Injeong, and Ruth E. Dunkle. 2010. “Worries, Psychosocial Resources, and Depressive

Symptoms among the South Korean Oldest Old.” Aging & Mental Health 14 (1): 57–66.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903420997.

Liang, Kun. 2014. “The Cross-Domain Correlates of Subjective Age in Chinese Oldest-Old.”

Aging & Mental Health 18 (2): 217–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.823377.

Lloyd, Liz, Michael Calnan, Ailsa Cameron, Jane Seymour, and Randall Smith. 2014. “Identity

in the Fourth Age: Perseverance, Adaptation and Maintaining Dignity.” Ageing &

Society 34 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000761.

Lowsky, David J., S. Jay Olshansky, Jay Bhattacharya, and Dana P. Goldman. 2014.

“Heterogeneity in Healthy Aging.” The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological

Sciences and Medical Sciences 69 (6): 640–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt162.

MacDonald, Maurice, Peter Martin, Jennifer Margrett, and Leonard W. Poon. 2009.

“Correspondence of Perceptions about Centenarians” Mental Health.” Aging & Mental

Health 13 (6): 827–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860902918249.

Mast, Benjamin T

., A. R. Azar, and S. A. Murrell. 2005. “The Vascular Depression Hypothesis:

The Influence of Age on the Relationship between Cerebrovascular Risk Factors and

Depressive Symptoms in Community Dwelling Elders.” Aging & Mental Health 9 (2):

146–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860412331336832.

McGinnis, Debra. 2009. “Text Comprehension Products and Processes in Young, Young-Old,

and Old-Old Adults.” Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and

Social Sciences 64 (2): 202–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp005.

Mitnitski, Arnold, Susan E. Howlett, and Kenneth Rockwood. 2017. “Heterogeneity of Human

Aging and Its Assessment.” Journals of Gerontology: Series A 72 (7): 877–84.

https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw089.

71

Downloaded on Mon Jun 29 2020 at 13:42:39 UTC

THE JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Moe, Aud, Ove Hellzen, Knut Ekker, and Ingela Enmarker. 2013. “Inner Strength in Relation to

Perceived Physical and Mental Health among the Oldest Old People with Chronic

Illness.” Aging & Mental Health 17 (2): 189–96.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2012.717257.

Momtaz, Yadollah A., Rahimah Ibrahim, Tengku A. Hamid, and Nurizan Yahaya. 2011.

“Sociodemographic Predictors of Elderly”s Psychological Well-Being in Malaysia.”

Aging & Mental Health 15 (4): 437–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.536141.

Muramatsu, Naoko, and Hiroko Akiyama. 2011. “Japan: Super-Aging Society Preparing for the

Future.” The Gerontologist 51 (4): 425–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr067.

Ness, Jose, Dominic J. Cirillo, David R. Weir, Nicole L. Nisly, and Robert B. Wallace. 2005.

“Use of Complementary Medicine in Older Americans: Results from the Health and