A Field Guide to

Washington

State

Archaeology

2003

A Field Guide to

Washington Archaeology

Sponsored by:

Washington State Department

of Transportation

Environmental Services Office

Point Plaza

P.O. Box 47332

Olympia, WA 98504-7332

Columbia Gorge Discovery

Center

5000 Discovery Drive

The Dalles, OR 97058

Washington State Parks and

Recreation Commission

7150 Cleanwater Lane

Olympia, WA 98504-2650

MaryHill Museum of Art

35 MaryHill Museum Drive

Goldendale, WA 98620

Office of Archaeology and

Historic Preservation

Office of Community

Development

1063 S. Capitol Way

Olympia, WA 98501

Western Shore Heritage

Services

8001 Day Road West, Suite B

Bainbridge Island, WA 98110

Authors:

M. Leland Stilson

Archaeologist

Department of Natural Resources

Land Management Division

1111 Washington Street SE

PO Box 47027

Olympia, WA 98504-7027

(360) 902-1281

FAX (360) 902-1783

Dan Meatte

State Parks Archaeologist

Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission

7150 Cleanwater Lane

P.O. Box 42650

Olympia, WA 98504-2650

(360) 902-8637

FAX (360) 664-0280

Robert G. Whitlam

State Archaeologist

Department of Community, Trade and Economic Development

Office of Archaeology & Historic Preservation

111 21st Avenue SW

P.O. Box 48343

Olympia, WA 98504-8343

360/586-3080

FAX 360/586-3067

We welcome all comments and suggestions for improvement. Please feel

free to contact the authors listed above.

A FIELD GUIDE TO

WASHINGTON ARCHAEOLOGY

Preface............................................................................................ i

Acknowledgments .................................................................... iii

1. What is Archaeology and

Why are Archaeological Sites Important? .............................. 1

2. The First People ............................................................................ 7

3. Archaeology of the West—

Saltwater Coasts, Rivers and Forests..................................... 13

4. Archaeology of the Mountains ................................................ 21

5. Archaeology of the East—

Rivers, Scabland and Plateau.................................................. 25

6. Historic Archaeology ................................................................. 35

7. Underwater Archaeology.......................................................... 45

8. What You Can Do....................................................................... 57

9. Folks Who Can Help You ......................................................... 61

Reading Lists and More.................................................................. 63

Glossary: Useful Terms .................................................................. 71

Appendix: (Related RCWs)

Chapter 27.34 RCW

Libraries, Museums, and Historical Activities ...................... A-1

Chapter 27.44 RCW

Indian Graves and Records ....................................................... A-3

Chapter 27.53 RCW

Archaeological Sites and Resources ........................................ A-7

Chapter 79.01 RCW

Public Lands Act ........................................................................ A-21

Preface

Archaeological sites are nonrenewable resources that contribute

to our sense of history and define our collective heritage. The

wise management of these resources is our responsibility.

This book provides an overview of the archaeological resources of

our state. It describes the discipline of archaeology, the kinds of

sites found in the state, and how to protect these important places

of our past. It was written as a field guide for personnel of the

Washington State Department of Transportation and State Parks

and Recreation Commission to help them address management

responsibilities for archaeological resources. It describes types of

sites that have been archaeologically investigated, offers

suggestions on site protection, and lists potential sources of help.

The reference section provides a list of books for further reading.

We hope you find this book useful and invite you to become a

steward of the past.

i

ii

Acknowledgments

This book is the product of a cooperative effort among agency

staff of the Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation,

Department of Transportation and the Washington State Parks

and Recreation Commission.

The authors extend their sincere appreciation to a number of

people whose efforts have made this project possible. Liz

Bradford, Project Manager, Forest Practices, Department of

Natural Resources, spearheaded this collaborative effort with Sara

Steel, Cultural Resource Information Director, Office of

Archaeology and Historic Preservation; Tom Robinson, Assistant

Manager, Forest Practices, Department of Natural Resources, kept

the original project schedule on track.

The Environmental Affairs Office of the Washington State

Department of Transportation joined the original training team as

a lead agency in 2000. Sandie Turner and her staff have provided

logistical, professional and financial support, as well as invaluable

management and coordination assistance.

The Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation’s College

Career Graduate, Amy Homan, has made all of the latest edits.

Nancy Charbonneau, Graphic Designer, Forest Practices,

Department of Natural Resources, designed and coordinated

publication. Drew Crooks of the Washington State Capitol

iii

Museum provided historic photographs. Dan Meatte, State Parks

and Recreation Commission, provided many other photos. We

also appreciate the technical assistance of Luis Prado, Graphic

Designer, Mark Macleod, Graphic Designer, Communication

Product Development; Carol Miller, Computer Information

Consultant; Glenn Shepherd, Cartographer, Forest Practices; Jari

Roloff, Geologist, Geology and Earth Resources; and Gina

Wendler, Word Processing Specialist, Forest Resources; all from

the Department of Natural Resources. Sara Moore provided

illustrations of Clovis Points.

iv

W

hat is Archaeology

Chapter 1

What is Archaeology and Why Are

Archaeological Sites Important?

A

rchaeologists study artifacts, features, and sites to

understand the human past. They borrow techniques

from sciences such as geology, biology, chemistry, and

physics to explain how human societies developed over time and

how they used their environment. Archaeology is a relatively

new field and is most commonly grouped with the social and

earth sciences.

There are three main goals of modern archaeology. The first goal

is to establish a chronological framework of the past. The basic

question is: How old is it? Archaeologists use a number of

techniques to establish the specific age of a site or the age of

specific types of artifacts.

The second goal of archaeology is to reconstruct the cultural

patterns and lifeways of a given culture in the past. The basic

question is: What did people do at this time and place in the past?

What were their lives and daily activities like?

The third goal of modern archaeology is to explain how cultures

have changed over time. The basic question is: What is the

character and cause of cultural change?

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

1

Chapter 1 What is Archaeology

In working to achieve these goals, modern archaeology seeks to

contribute to the better understanding of how we as a

community, state, nation, and humanity as a whole came to be.

Archaeology, with other social and natural sciences, presents us

with a fuller understanding of who we are and where we came

from.

Archaeology is not about the collection of artifacts for collecting’s

sake. Rather, archaeology is about the acquisition of information

about the past and applying that information to help understand

the human past. It provides long term insight to contemporary

problems such as the sustainability of different agricultural

techniques, the containment of toxic waste, and the impact of

environmental changes upon society.

Archaeologists identify and study archaeological sites. These

sites represent places on the landscape where people lived and

carried out daily routines, leaving artifacts and other material

remains that shed light on their activities.

2

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

W

hat is Archaeology

Chapter 1

Sites

Archaeological sites can range in size and complexity from large

permanent village sites to smaller single use hunting camps.

Archaeological sites are found in every county in the state and in

every environment.

The ages of these sites date from 12,000 years ago to recent

historic time. The way the sites were created and preserved

varies widely. Some archaeological sites, such as alignments or

cairns, were purposely built out of permanent materials such as

stone. Other sites were preserved when they were rapidly buried

by landslides or flooded by water.

Despite the circumstances of their preservation, archaeological

sites and the artifacts they contain represent a fraction of past

cultures’ material and intellectual heritage. More importantly,

social behavior, ideas, and beliefs are not directly preserved and

can only be indirectly reconstructed by archaeologists.

By studying those artifacts that do remain, archaeologists can

construct a narrative of what people did in the past in very

specific terms at that locale. Like any proposed model, as more

information and knowledge is gained, a fuller picture emerges.

Archaeological sites also contain information on past

environments and the plant and animal life associated with those

ancient times. Archaeological sites are a repository of a wide

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

3

Chapter 1 What is Archaeology

range of natural resource information ranging form biogeography

of specific animal and plant species to the climate and weather

patterns of the past.

Recent research in coastal Washington has focused upon

prehistoric earthquakes. Archaeologists are now working with

geologists to precisely date earthquakes based on archaeological

data.

Archaeological sites are like ancient books. Reading those books

can educate us all. Old books are fragile, however, and can be

destroyed if they are not treated with care and respect.

How Archaeological Sites are Found

There are more than 14,000 site forms on file with the Office of

Archaeology and Historic Preservation, the earliest date from the

early 1950’s. Each month an average of 20 new sites are recorded

with the Office.

Archaeological sites can be found anywhere -- in forests,

orchards, or cities; on beaches or mountain tops, beneath

buildings, and even underwater. They can be on public land,

tribal reservations, or private property. They may be accidentally

uncovered during construction projects or discovered during

carefully planned systematic surveys by archaeologists.

4

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

5

W

hat is Archaeology

Chapter 1

An archaeological survey involves several steps. In the first step,

before going into the field, we review existing information: site

records from the area, historic documents, and the results of

previous research. Other sources may include ethnographic

accounts of local tribes, land

records, and aerial

photographs. Topographic

maps can help us identify

land forms or locales in the

project area that should be

inspected. We also get

permission of the landowner

and contact concerned tribes

and other researchers

interested in the project.

The second step is the field

survey when archaeologist

physically inspect the project

area. The exact survey

methods are based on the

research design developed as

a result of the literature and

records review. Most

commonly, the ground

surface is carefully examined

in evenly spaced transects

over the entire area.

Using an auger to check for the presence of

subsurface archaeological materials.

Credit: Office of Archaeological and Historic

Preservation

Chapter 1 What is Archaeology

Depending upon plant cover and soils, we may examine

subsurface soil cores or clear the forest litter from the surface to

check for evidence. If a site is found, we collect location and

descriptive information on a standardized form to register it with

the Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation.

The third step is writing the survey report which summarizes our

research and field efforts and offers recommendations. The report

is sent to the landowner or land manager and the Office of

Archaeology & Historic Preservation. Even when no sites are

found, we prepare a survey report to describe the inspected area

and the survey methods.

Our goal is to find and document these special places of our past

to protect them for future study and appreciation.

6

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

7

The First People

Chapter 2

T

The First People

here are two main ideas on how people first came into the

western hemisphere, including that area now known as

Washington State. Both agree that the ancestors of the

historically known tribes came from northeast Asia.

The most accepted idea is that prehistoric hunters, following large

herd animals, crossed a massive coastal plain known as Beringia

which was exposed when sea levels dropped during the last great

Ice Age, 25,000 to 12,000 years

ago. As the continental ice

sheets receded and glaciers

retreated to alpine settings, a

pathway known as the Ice Free

Corridor, opened to the more

temperate regions of the south.

By 12,000 years ago, the

hunters were moving into

what is now the United States

and settling into a variety of

landscapes.

The competing idea is that people came down the shoreline. With

world sea levels as much as 100 meters below present levels, an

ice free corridor may have existed along the coast. People

traveling along this route would probably have depended on sea

and river resources rather than land animals.

East Wenatchee Clovis site excavation showing

Clovis Points. Credit: Office of Archaeology and

Historic Preservatio

n

Chapter 2 The First People

8

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Archaeologist in the laboratory cataloging artifacts. Credit: Julie Fields, University of Washington

The First People

Chapter 2

The first definitely dated culture in the New World is known as

Clovis. The large fluted projectile points of these people are

found throughout the lower 48 states. Until recently, only a

dozen or so isolated Clovis points had been found in the state.

However, in 1987 in East Wenatchee, a cache of beautiful,

translucent chalcedony and jasper Clovis points and other tools

were discovered by workers excavating an irrigation line in an

apple orchard.

Two seasons of archaeological work at the site revealed a feature

containing a distinctive assortment of 57 finished artifacts.

Nearby, a second, smaller feature was discovered which

contained several more artifacts of similar manufacture.

One interpretation is that the artifacts are part of a tool kit, stored

on a prominent hilltop overlooking a likely hunting spot,

suggesting that the hunting tactics of Clovis people involved

long-term planning. The positioning of necessary gear near

potential kill sites implies repeated visits and a predictable

seasonal round. Protein analysis of blood residues preserved on

the stone tools revealed the blood of human, deer, rabbit, and

possible an extinct form of bison.

Elsewhere in Washington, archaeologists discovered evidence of

everyday life of 10,000 years ago. At Lind Coulee, near Moses

Lake, they uncovered the butchered remains of bison along with

people’s everyday tools and personal effects. Several small,

delicate bone needles suggest that leather clothes were sewn for

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

9

Chapter 2 The First People

10

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

warmth and protection. Small stone pallettes were stained with

red and yellow ochre. This indicates that colored pigments may

have been used for decorating clothing or skin.

Other information about the diet of the state’s early inhabitants

comes from discarded food remains preserved in large volcanic

caves common to the arid scablands of east-central Washington.

Excavations at one cave, Marmes Rockshelter, near Lyons Ferry,

Franklin County, revealed that a wide variety of game animals

were used for food or hunted for materials such as pelts, horn or

teeth. Many plants were used for food or medicinal purposes.

Such a diverse and varied diet implies that the early inhabitants

maintained a highly flexible lifestyle capable of adapting to the

changing conditions of climate and environment of prehistoric

eastern Washington.

The nature of the early

occupation in western

Washington is more difficult

to determine. To the north,

in British Columbia,

maritime shell midden sites

date to at least 10,000 years

ago. In Oregon, similar sites

are known to date to 8,000

years ago. In the early

levels of the Marmes site,

Excavations at Marmes Rockshelter. Credit: Office of

Archaeolo

gy

& Historic Preservatio

n

The First People

Chapter 2

Pacific seashells were found indicating that coastal and inland

inhabitants had established trade routes at least 7,000 years ago.

However, the oldest securely dated coastal shell midden site in

Washington is only approximately 4,000 years old.

Shell middens usually occur just above the mean high tide line.

Here they are vulnerable to sea levels that have been rising since

the end of the last ice age. This is the best explanation for the lack

of older shell midden sites.

The oldest known site in the state which demonstrates an

adaptation to river resources is Avey’s Orchard in Douglas

County, which dates to at least 10,300 years ago. The 5 Mile

Rapids site on the Oregon side of the Columbia River across from

Klickitat County dates to 9,785 years ago. The lower levels of this

site contained more than 200,000 salmon bones and some seal

bones.

The antiquity of the marine/riverine adaptation of the prehistoric

in habitants of the state must date back to at least 12,000 years.

Underwater work along the continental shelf and in Puget Sound

will provide exciting information on the initial peopling of the

New World.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

11

Chapter 2 The First People

12

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts and Forests

Chapter 3

Archaeology of the West --

Saltwater Coasts and Forests

N

orthwest Coast societies broke the anthropological rule

that agriculture is necessary for large complex villages.

On the Washington coast and along major rivers, people

lived in large villages where monumental architecture and

elaborate art flourished. The economic basis for these societies

was the harvest and storage of salmon, coming in dense,

predictable runs.

The families of the coast and forests moved with the seasons.

Usually, they lived in a village during the winter. When

resources became seasonally available, families would leave the

village and camp near those resources to collect and process them

for storage. This type of residence and economic system is known

as a “seasonal round” and produces a large number and wide

variety of sites -- spring root camps, summer fishing camps, fall

hunting camps, and sheltered winter villages. Many activities

took place at these sites. There were also spots where only a

single activity occurred, such as logging or bark-stripping sites,

rock quarries, burial islands, or areas that had religious and

spiritual meaning such as pictographs and petroglyphs.

There are several implications of this seasonal round for

archaeological interpretation:

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

13

Chapter 3 Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts, Rivers and Forests

14

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

1. No one site will contain all the tool types and materials used

by a people. Sites in differing environments will contain

different artifacts and animal and plant remains. By analogy,

the tools and materials you have at home are different from

those you have at your office.

2. To understand the archaeology of an area, archaeologists have

to identify all types of sites of a group. Sites from the same

time period, occupied by the same people, will vary in size,

artifact content, duration of use, and preservation qualities.

For example, to understand our present culture, we would

need to examine sites as diverse as primitive area campsites

and large metropolitan cities.

Typical archaeological sites of western

Washington include the following:

Shell Middens

Shell Middens are villages, camp sites, or

shellfish processing areas, composed of a

dark, organically rich soil with shell or

shell fragments, artifacts and fire-cracked

rock. These sites are found along the

saltwater shorelines of western

Washington. The village or residential

sites may have rectangular house

depressions and will be near a source of

fresh water. Most of the state’s marine

Exposed shell midden deposits

at Reid Harbor, Stuart Island

State Park. Credit: Dan Meatte.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

15

Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts and Forests

Chapter 3

shell middens are less than 3.000 years old, the date when the

current sea level stabilized.

Old Man House State Park at Suquamish is an example of a

village site. People processed shellfish at the Manette site near the

Manette Bridge in Bremerton.

Open Sites or Campsites

These sites are mainly found along rivers and streams and inland.

They contain lithic artifacts and flakes of fire-altered rock. Some

have small amounts of shell and bone. They are seasonal living

sites or short-term camps where people fished, hunted or

gathered plants. Fishing sites such as Tualdad Altu in Renton

and Marymoor Park on the Sammamish River have high

percentages of blades or microblades (thin narrow flakes of stone)

used for filleting fish.

Pictographs and Petroglyphs

A pictograph is an image drawn

on a rock surface with a mixture

of pigments that can include

ochre, charcoal or other plant

and animal materials. A

petroglyph is an image pecked

into a rock surface. Images are

geometric, human or animal

forms. Many petroglyphs are

Rubbing from Petroglyph on beach boulder

at Wedding Rocks. Credit: M.L. Stilson

Chapter 3 Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts, Rivers and Forests

found on prominent boulders along the shoreline or on rock

outcrops.

There is a southern Puget Sound petroglyph complex

characterized by curvilinear faces and designs which occur on

beach boulders near or below the high tide line often near village

sites. Northern Puget Sound rock art sites are also found on

beach boulders. Easily accessible sites include Lime Kiln

Petroglyphs on San Juan Island and the Wedding Rock

petroglyphs near Cape Alava.

Caves or Rockshelters

Caves or rockshelters used as living areas or camping spots, are

rare in western Washington. They offer the potential for well-

preserved deposits. Judd Peak and Layser Cave have yielded

information on the use of the foothills of the Cascades from 6,700

years ago to 400 years B.P.

Wet Sites

These are rare sites in which normally perishable materials like

basketry, wooden artifacts, or wool and hair are preserved,

usually because they are saturated by water. Wet sites offer a

more complete picture of people’s artifacts, tools and materials.

On the Northwest Coast, an estimated 60 to 90 percent of artifacts

were made of wood or fiber. Wet sites offer us a glimpse of these

elements, which typically do not survive in other types of sites.

Wet sites can be sections of whole villages such as Ozette, over

16

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

17

Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts and Forests

Chapter 3

bank refuse deposits such as Biderboost on the Snoqualmie River

or Hoko on the Hoko River, or fish weirs such as Wapato Creek

Fish Weir in Tacoma.

Culturally Modified Trees

(CMTs), Basket Trees or

Peeled Cedars

These are living cedar trees

from which bark has been

stripped or planks split off

their sides. The bark was used

for making baskets or clothing.

The planks were used in

buildings or making boxes.

CMTs are frequently found in

old growth stands of cedar.

The cultural modifications on

some CMTs have been dated

to 300 years ago. In a recent

study on the Makah Indian

Reservation, archaeologists

identified eight different types

of CMTs, including plank-

stripped logs, cut logs, notched

trees and chopped trees.

Partially finished canoes have

also been found.

Culturally Modified Tree. Deep notching is the

first step in removing a plank. Credit: Office of

Archaeology & Historic Preservation

Chapter 3 Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts, Rivers and Forests

Burial Sites, Islands, or Cemeteries

The locations of burial sites varied over time and among groups.

In some parts of western Washington, small off-shore islands or

wooded slopes adjacent to villages were cemetery areas. Isolated

burials are found in a variety of locations. Shortly after

Euroamerican contact, entire villages were decimated by disease

and thus became cemeteries. Please respect all these areas and do

not disturb them.

18

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

19

Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts and Forests

Chapter 3

Artifacts, Flora and Fauna

Native Americans made tools from stone, bone, antler

and wood. They made projectile points from the dark

basalts found along rocky beaches. Points, fish hooks

and harpoons were made from antler, bone and

wood.

Harpoon lines were fashioned from twisted cedar.

Clothing was made from woven cedar bark, spruce

roots and fur.

Northwest Coast societies did not make pottery.

People boiled water and cooked food in watertight

wooden boxes or baskets by heating rocks and

dropping them into the water. As a result, a major

component of site are fire-cracked rocks, reddened or

blackened by fire and then broken in the cooling

process.

Besides artifacts and fire-altered rock, sites contain

much biological data. Shellfish remains can help

identify the species that were used for food,

materials or decoration and can provide evidence on

the local environmental setting. Archaeologists use

bird remains, fish and land mammal bones to

reconstruct the diet and time of year the site was

occupied and carbonized plant remains, pollen and

charcoal to reconstruct the local ve

g

etation. The

y

Chapter 3 Archaeology of the West -- Saltwater Coasts, Rivers and Forests

also use the new DNA techniques to analyze the amino acids

preserved on stone tools to identify the species of animals killed

and butchered by those tools.

20

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

21

Archaeology of the Mountains

Chapter 4

M

Archaeology of the Mountains

ost residents of Washington know that Native Americans

lived among and used the coast, rivers and forests, but

there is also evidence they used the mountains for more

than 8,000 years for a variety of resources that included game,

plants and raw materials such as stone, wood and wool. The

mountains were also places of spiritual renewal.

Research in the mountains has

documented a variety of site types.

Lithic Sites

Small scatters of stone artifacts on

the surface of the ground are

called lithic sites. They range from

short encampments to locations

where someone stopped

momentarily to resharpen or make

a stone tool. Lithic sites in the

Chester Mores Reservoir were

used for at least 8,000 years from

8,500-700 B.P.

Archaeologist holding rock hammer and

flake at stone quarry site. Credit: Office of

Archaeology and Historic Preservation.

Chapter 4 Archaeology of the Mountains

22

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Quarries

Sites where stone for making tools could be procured are called

quarries. Quarries are usually stone outcrops that have evidence

of stone flaking and tool manufacture. Common artifacts are

cores and flakes. Some quarries were used for thousands of years.

Desolation Chert Quarry in Whatcom County was used from

7,640-290 B.P.

Camp and Village Sites

These are residential sites occupied for varying lengths of time --

temporary stopovers or longer seasonal encampments. Most are

found along major rivers and streams. They are characterized by

artifacts, fire-cracked rock, and associated hearth and storage

features.

Rock Structures

Purposefully stacked or

aligned rocks are found in

a number of areas. Called

cairns, these structures

covered burials or were

used as a focus for the

vision quest experience.

Native Americans also

used rock features in

Prehistoric linear rock alignment found on DNR land

in the Columbia Gorge near Stevenson, Washington.

Credit: Office of Archaeology and Historic

Preservation

Archaeology of the Mountains

Chapter 4

hunting or driving game, in storing of gathered food and for

marking trail or resource areas.

Huckleberry Trenches

The trenches are low swales and shallow rectangular depressions.

Berries were placed on mats in these depressions. A smoldering

fire in a log served as a source of radiant heat to dry out the

berries. Archaeologists have identified eleven huckleberry

processing sites in the Indian Heaven Wilderness of the Gifford

Pinchot National Forest. The elevations of these sites range from

3.000-5,000 feet.

Artifacts

Artifacts found in the mountains reflect the activities carried out

there. Projectile points were used in hunting. Lithic flakes and

cores are found at quarry sites, where stone tools were made.

Only recently have archaeologists studied the mountains of our

state. This information can help us understand the natural history

of the mountains. For example, Carbon 14 dates from

huckleberry trenches provide information on forest fire history

and tree species succession in the forested mountains of

Washington.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

23

Chapter 4 Archaeology of the Mountains

24

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Flake

Scars

Exterior Surface

Artifact vs.

Nature-fact

Archaeologists often rely on small

clues to locate prehistoric

archaeological sites. Easily

recognized items like arrowheads,

stone mortars,

or carved bone

tools are not

always present.

More often, only

a few small flakes

of stone mark the

presence of a site.

Small flakes of stone

are also produced

naturally. However,

archaeologists can

distinguish flakes

produced by humans

from those produced naturally.

When humans strike stone with a

direct blow, a bulb of percussion is

formed. This is one of the easiest

ways to tell an artifact from a

nature-fact.

Point of Impact

Bulb of Percussion

Interior Surface

Ri

pp

les

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

25

Archaeology of the East - Rivers Scabland and Plateaus

Chapter 5

T

Archaeology of the East --

Rivers, Scabland and Plateau

he Channeled Scabland and surrounding hills were home

to many Native American groups whose ancestors had a

flexible lifestyle suitable to this arid setting

The Scabland is part of a lava plateau covered with sagebrush and

bunchgrass and broken into a mosaic of basalt outcrops,

intermittent streams, and playa lakes. The area is encircled by

two major rivers, the

Columbia and the

Snake. Before the

rivers were dammed,

they teemed with

salmon that

supported the

cultures of this

region. Fishermen

used spears, large dip

nets, and extensive

networks of wooden

platforms perched

over the river’s edge to harvest the fish. Fishermen hauled the

catch to the river bank to be cut, dried or smoked, and then

transported the preserved meat to the main villages to be eaten

during the long winters.

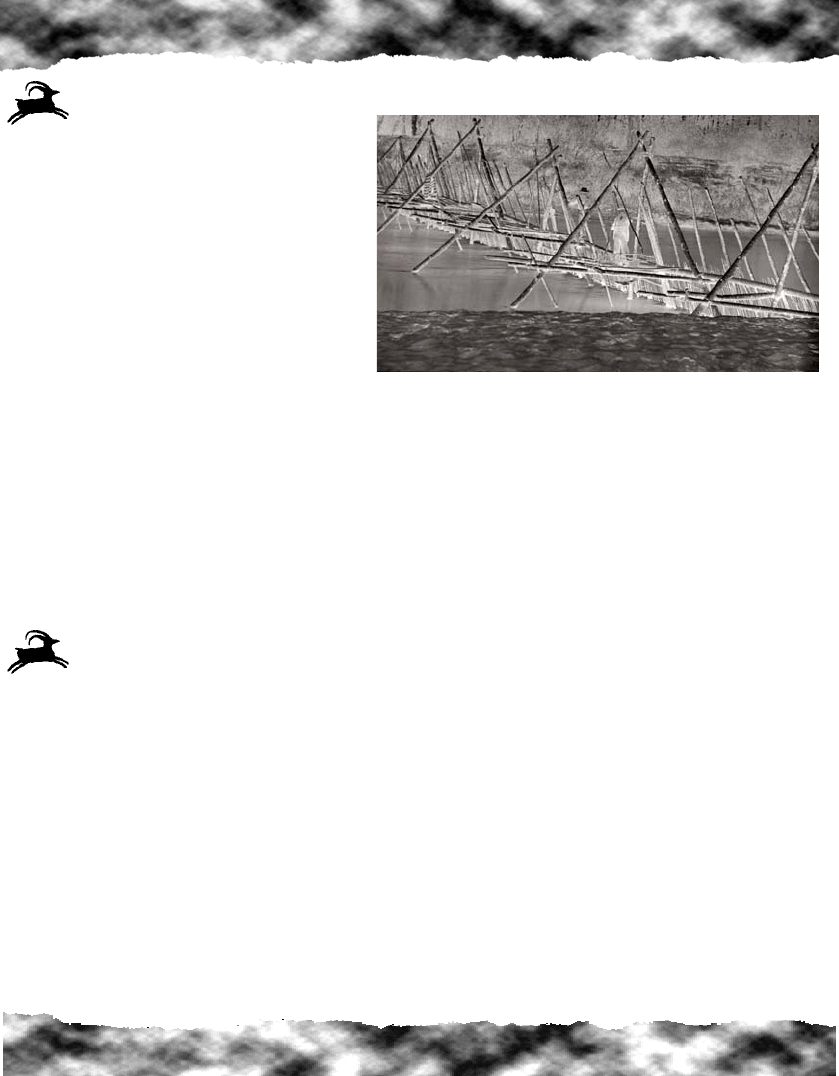

Fishing at Celio Falls in 1953. Credit: Oregon Historical Society

Chapter 5 Archaeology of the East -- Rivers, Scabland and Plateaus

26

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

The people hunted deer, antelope, mountain sheep, elk and bison

either individually or in groups. They collected food plants from

the prairies dotting the broad upland valleys of the surrounding

plateau. Camas, a brightly flowered plant with a large onion-like

bulb, was one of the most important foods. It was harvested in

the late spring with a simple digging stick. Using mortars and

pestles, the people crushed the starchy bulb and then cooked the

roots in earthen ovens. Plants also served as a living pharmacy of

medicinal compounds for curing a variety of ailments. Following

their elders’ teachings, many Native Americans continue to

harvest and use these healing plants today.

Thousands of

archaeological sites

spanning over

13,000 years have

been recorded in

the Scablands and

Plateau region.

They range from

simple flake

scatters to large

villages, and can be

grouped into

several categories.

Outline of housepit depression. Credit: Office of Archaeology &

Historic Preservatio

n

Archaeology of the East - Rivers Scabland and Plateaus

Chapter 5

Residential Sites

The typical house of the region was the pithouse, which was semi

subterranean. The builders dug a large oval or circular hole to a

depth of up to 12 feet, and then constructed a roof of poles, brush,

or mats and dirt. They left a hole in the center of the roof for an

entryway and to allow smoke to escape. Oval pithouses were up

to 156 feet long and 20 feet wide and were excavated to a depth of

three feet. Circular housepits were up to 50 feet in diameter and

12 feet in depth. Not all residential structures in the area were

housepits. Mat lodges and tipis were also used.

Complete pithouses are seldom preserved. Commonly, only the

debris left on the floor after the house is abandoned remains.

They are usually found on low river terraces where past flood

episodes have filled them with sediments leaving only shallow

depressions on the surface. Soil exposures or cuts into the

terraces expose long thick bands of dark stained soil containing

artifacts, bone, river mussel shell, and charcoal. A good example

of a pithouse village is the Rattlesnake Creek Site located on

Department of Natural Resources lands in Klickitat County

northeast of Husum.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

27

Chapter 5 Archaeology of the East -- Rivers, Scabland and Plateaus

Pithouse cross-sections

Possible locations of features that archaeologically may indicate the nature of the superstructure of

pithouses. A. cross section of subterranean excavated dwelling; B. cross section of dwelling within an

excavation. In B and C, post molds may or may not be present, depending on the method of

construction. If post molds are present, they probably will be found only at rafter/frame element

locations, not continuously along an entire “wall”.

28

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

29

Archaeology of the East - Rivers Scabland and Plateaus

Chapter 5

Typical projectile point. Credit: Dan Meatte

Hunting Sites

Ancient hunters sometimes

stalked one animal at a time

and sometimes chased entire

herds. They developed

hunting techniques for the

kind and number of game

sought. For example,

hunters might startle deer

into traps, using long fences

built of stacked rock to direct them. They killed mountain sheep

using systems of hunting blinds and pocket traps. Often the

hunters took advantage of the landscape, incorporating isolated

buttes, blind canyons and playa lakes into communal hunting

strategies.

Lithic Scatters

When hunters stopped to rework a dart point, arrowhead or other

stone tool, they left small scatters of flaked stone. At these

scatters, archaeologists have found flakes of obsidian, chert,

chalcedony, petrified wood and jasper.

Fishing Sites

Archaeologists have recovered the remains of fish from many

archaeological sites along the region’s rivers. Because fishing

Chapter 5 Archaeology of the East -- Rivers, Scabland and Plateaus

30

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

camps were located on

riverbanks, many fishing

sites were washed away

during annual spring

floods. However

archaeologists have

recovered preserved

netting, fish hooks, bone

spear points, hafted knives

for cleaning fish, and other

equipment from dry caves

and rockshelters where

they were stored.

Remnants of stone fish weirs have been discovered in rivers and

streams. A series of sites from Kettle Falls in Stevens and Ferry

Counties were used for fishing, possibly as long as 9,000 years

ago. These sites continued to be used up to historic times.

Gathering Sites

The harvest and processing of plants for food and materials

required an assortment of tools: hafted knives, digging sticks,

and large burden baskets capable of holding large quantities of

roots, tubers and berries. Native Americans used several kinds of

ground-stone tools to crush roots and tubers into food pastes that

were cooked or mixed with other foods. Archaeologists find

stone mortars, pestles, grinding slabs and milling stones near

Stratigraphy of a fishing site with Mount St. Helen’s Y

Ash dated between 3,300 and 3,500 years ago. Credit:

Office of Archaeolo

gy

& Historic Preservatio

n

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

31

Archaeology of the East - Rivers Scabland and Plateaus

Chapter 5

popular harvesting grounds. Many earth ovens are also found

near some of the richest harvesting grounds. Archaeologists have

identified and excavated hundreds of camas ovens along the Pend

Oreille River. The dates on these sites range from 7,200 - 300 B.P.

Hopper mortar showing circular wear

area. Credit: Dan Meatte

Chapter 5 Archaeology of the East -- Rivers, Scabland and Plateaus

32

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Earth oven illustration.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

33

Archaeology of the East - Rivers Scabland and Plateaus

Chapter 5

Pictographs and Petroglyphs

Pictographs and petroglyphs are

commonly found on rock out-

croppings along major river systems

and coastal areas in

Washington State.

This rock art encom-

passes a variety of

representations:

circles, lines, dots,

jumping mountain

sheep, running elk

and ghostly human

figures.

How Sites are

Identified

Sites are identified using a

system developed by the

Smithsonian

Institution. Every

archaeological site in

the United States is

assi

g

ned a distinctive

three-part identifier.

The first element

is the state identifi-

cation. Washington

is represented by the

number 45. Next

comes the abbrev-

iation for the county

the site is in: WH for

Whatcom, PI for

Pierce, SA for

Skamania,

SP for Spokane, AS for Asotin

and so on. Last comes an

individual site number. This

is assigned by the Office of

Archaeology and Historic

Preservation and is usually

sequential. Therefore

45CA24, the Ozette site, is the

24

th

site recorded in Clallam

County and Astor Fort

Okanogan is 45OK65 for the

65

th

site recorded in

Okanogan County.

Tsa

g

a

g

lalal; “She who Watches” a

petro

g

l

y

ph at Horsethief Lake State

Park. Credit: Dan Meatte,

Washington State Parks

Excavated Camas oven. Credit: Office of Archaeolo

gy

& Historic Preservation

Chapter 5 Archaeology of the East -- Rivers, Scabland and Plateaus

34

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Necklace of dentallium shells, abalone and glass beads. Glass beads were one of the first

Euroamerican trade items in Washington State. Credit: State Capitol Museum, a division of the

Washin

g

ton State Historical Societ

y

.

Historic Archaeology

Chapter 6

Historic Archaeology

W

hen people think of archaeology, they usually relate the

term to ancient peoples and sites. However, more recent

peoples also have left traces of their lives. Telling the

story of the Euroamerican influence in Washington State is the

focus of historic archaeology.

The historic period has two major divisions -- protohistoric and

historic. The protohistoric period is that time between the

prehistoric and historic when native cultures and sites are affected

by Euroamerican influences but before they enter the stream of

written history.

Many prehistoric sites have a protohistoric or historic overlay.

This is because many sites continued to be occupied after

Euroamerican contact. Ozette on the Pacific coast, Old Man

House near Suquamish on Puget Sound, and 45SA11 on the

Columbia River near Skamania just down-stream from the

Bonneville Dam are examples of sites with prehistoric,

protohistoric and historic components. Other sites such as

Sba’badid in Renton were occupied only in the protohistoric

period.

Historic archaeology utilizes most of the same tools as does

prehistoric archaeology, but additional resources area available

for interpreting sites. These include paintings, photographs,

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

35

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

pictures, journals, maps, sketches, census data, newspaper

accounts, company records and diary entries.

Sometimes these materials allow archaeologists to identify the

names of inhabitants of a specific house.

In historic archaeology the identification of artifacts and their

functions is less speculative. Categories of functions include

architecture (nails, window glass, bricks), personal items (buttons,

buckles, jewelry, beads, combs,

pocket knives), personal

indulgences (alcohol bottle glass,

tobacco pipes), domestic

(ceramics, tableware, culinary,

furnishings), commerce and

industry (coins, armaments, and

tools).

Historic sites include fur trade

camps, military forts, pioneer

homesteads, small towns, logging

and mining camps, railroad

camps, bridges, trestles, fords, and

religious centers such as missions.

These categories are not mutually

exclusive. Small villages or towns

grew up around military or fur

trade forts.

Base of 1833 Fort Nisqually stockade all

exposed during excavations. Credit: Office of

Archaeological & Historic Preservation.

36

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

37

Historic Archaeology

Chapter 6

Fur Trade

The initial Euroamerican occupations in the state were fure trade

establishments. Known as “forts”, these were not military but

commercial establishments. Initially, some did not even have

protective fortifications.

The fur trade has been the main focus

of historic archaeologists in the state.

This is reflected in the list of Pacific Fur

Company and Hidson’s Bay Company

forts that have been excavated. These

include Fort Spokane near Spokane,

two different Fort Okanogans where

the Okanogan River meets the

Columbia, Fort Nez Perce at the

junction of the Snake and Columbia

Rivers, Fort Colville near Kettle Falls on

the Columbia River, Fort Vancouver

and Kanaka Village in present-day

Vancouver, two Fort Nisquallys and

Nisqually Village near the present-day

town of DuPont, and Bellevue Farm on

San Juan Island.

The fur trade in the Pacific Northwest

was controlled by corporate giants,

especially the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Hudson’s Bay Company period

(1820-1860) ceramic ink bottle

from underwater trash deposits

at Fort Vancouver, Washington.

Credit: Aquatic Resources

Division, DNR.

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

38

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

The archaeology of the fur trade is divisible into at least two

categories, fort and village. The layout of Hudson’s Bay

Company forts is rigidly patterned and predictable. The building

styles and techniques are standardized. The inhabitants within

the forts were predominately Scottish or English, male and upper

middle class. In contrast, the villages outside the forts were much

less standardized and predictable. The socio-economic status of

the inhabitants tended towards the middle to lower classes.

Building styles and techniques were diverse, reflecting the widely

diverse ethnicity of the village inhabitants -- French Canadian,

Hawaiian, Iroquois, Scottish, and local Native American. Women

and children abounded.

Many early pioneer settlements were located no farther than a

day’s journey from the major Hudson’s Bay Company supply

centers. Examples include Tumwater, Yelm, and Steilacoom.

These, in a sense

were also outposts of

the Hudson’s Bay

Company where

inhabitants often

worked as day

laborers at various

Hudson’s Bay

Company forts.

Pioneer families

survived in part

because of the help

they received from

Historic ceramics on surface of forest floor. Credit: Office of

Archaeology & Historic Preservation.

Historic Archaeology

Chapter 6

Native Americans and the Hudson’s Bay Company. Pioneer

families sometimes operated as independent traders. An example

of freelance traders comes from the remains of a historic store or

trading post at 45SA11 in Skamania County along the Columbia

River, which was occupied during the 1850s and probably burned

in 1856.

As the fur trade faded and the number of pioneer families

increased, the emphasis of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the

smaller entrepreneurs changed. Instead of furs, they increasingly

dealt in consumer goods. Fort Nisqually and Cowlitz Farm were

pastoral and agricultural branches of the Puget Sound

Agricultural Company, a subsidiary of the Hudson’s Bay

Company that shipped wool, hides, tallow and salt beef to

London, supplied agricultural goods to various Hudson’s Bay

Company establishments and even maintained a herd of dairy

cows to supply butter to Russian America. Hudson’s Bay

Company trading establishments soon began supplying more

household goods -- such as clothing, dishes, pots and pans, and

building materials -- than the classic artifacts of the fur trade --

guns, beads, blankets, tobacco pipes and bottles of rum.

Missions

Religious organizations founded missions to minister to the

spiritual needs of pioneer families, Hudson’s Bay Company

employees and Native Americans. They often arrived only a few

years behind the fur trade forts. Archaeologists have investigated

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

39

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

the Richmond Mission near the original Fort Nisqually, Whitman

Mission near the present town of Walla Walla, and St. James

Mission, which was founded at Fort Vancouver.

Some missions drew their goods directly from fur forts, and these

artifacts are nearly indistinguishable from those of a fur trade

village family. Because many of these sites also functioned as

schools, there are many slate-writing implements -- slate tablets

and octagonal or round slate “pencils”. There is usually a “great

room” used for congregational meetings. These artifacts from the

American Methodist missions are characterized by the almost

complete absence of clay tobacco pipes and alcoholic beverage

bottles.

Military

With the resolution of the boundary between British and

American lands at the 49

th

parallel in 1846, U.S. military outposts

became necessary to protect settlers and to establish an American

presence. Early U.S. Army posts include Fort Lugenbeel on the

Columbia River near the town of Stevenson, Fort Steilacoom near

the town of Steilacoom, Fort Townsend south of Port Townsend,

and Fort Walla Walla, near the city of Walla Walla, all established

in the 1840s and 1850s. A U.S. Army post was also set up at Fort

Vancouver. Additional boundary disputes over the San Juan

Islands during the 1850s led to the establishment of American

Camp and British Camp on San Juan Island. The latter was a

military outpost of the British Marines. All of these sites have

40

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Historic Archaeology

Chapter 6

been excavated to some extent.

Military forts were built according to standardized military

protocol, even down to the number of nails used in a particular

joint. Ceramics tend to be white earthenware. Military

accouterments such as buttons and insignias are common.

Small Towns

As pioneer families and settlements proliferated, small towns

were formed. The towns that have been archaeologically

investigated range from those founded in the 1840s and 1850s,

Tumwater and San Juan Town on San Juan Island, to those

founded in eastern Washington in the 1880s, Riparia and Silcott.

Some small towns were set up for specific purposes. Joso Trestle

was a construction camp devoted to railroad construction.

Franklin, near the present town of Black Diamond, was

established to mine coal. A lumber mill complex including two

mills, a power house, barns, houses, a cook house, store and a

Japanese village is known from the Howard Hanson dam

reservoir in King County. Of all these communities, only the first,

Tumwater is still a living community.

Homesteads

Homesteads range from the mid-19

th

century to the early 20

th

century. They include a mid-19

th

century homestead at

Chamber’s Farm near Olympia and a number of homesteads from

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

41

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

the early 20

th

century mapped during the Chief Joseph Dam

project in Douglas and Okanogan Counties. Archaeologists have

investigated numerous single family homesteads. Typically,

homestead sites consist of single dwellings with barns, fences,

and outbuildings. At some homesteads more recent houses are

also present. because many different time periods are represented

in this group, artifacts range from fur-trade types of artifacts to

early 20

th

century Sears and Roebuck mail order items.

Logging, Mining, Railroad Features

Logging features can include road grades, landings, spring board-

cut trees, old logging donkeys, cables and other logging

equipment. Mining features include the mines themselves, spoils

piles and extractive machinery. Railroad features can include the

railroad grades and trestles.

42

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Historic Archaeology

Chapter 6

How Archaeologists Tell Time

Radiocarbon dating is one of the most

important tools available for

establishing the age of buried sites

and objects. Yet it can only work on

ob

j

ects derived from or

g

anic materials

such as plants and animals. Many

artifacts are inorganic (such as metal

or stone) and cannot e radiocarbon

dated.

Archaeologists developed a technique

for dating items based on the

changing styles of shape and

manufacture. The technique is called

seriation. Tools and techniques of

manufacturing those tools change

through time. By examining and

comparin

g

the artifacts found in lower

levels with those from the upper

levels of a site, we gain an idea of how

the style of a particular item, say a

projectile point, changed through

time. When similar objects are found

at another site, they can be compared

to the other style sequence to

determine a relative date. This is

essentially the same technique used

by car buffs who can identify a 1957

Chevy or a 1965 Ford.

You can use this tecnique yourself to

1974

1962 - 1974

1972 - Present

1935 - 1962

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

43

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

44

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

45

Underwater Archaeology

Chapter 7

Shipwreck “Austria” at Ozette village, circa 1880. Credit: State

Capitol Museum, a division of the Washington State Historical

Society.

P

Underwater Archaeology

rehistoric and early historic sites are usually found

adjacent to navigable waters. The economic systems of

Native Americans and early Euroamericans were oriented

to river, intertidal and marine resources. Boats were the

dominant mode of transportation in the state until World War II.

Since many prehistoric and historic settlements were near the

water, since economic activities occurred in water, and since most

prehistoric and historic transportation was by water, many items

of archaeological interest ended up under water.

Artifacts and features can be lost or intentionally placed in the

water. Sites can be flooded by water behind dams or covered by

naturally rising water.

Lost/Accidental

Shipwrecks

Boats and ships are

among the most

complex sites or

features to end up

under the water.

Shipwrecks can be

separated into five

categories, ranging

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

from fully intact ships to scattered remnants of cargo on the sea

floor. Scattered remains may be indistinguishable from trash

dumps. Shipwrecks can occur in all acquatic settings, from deep

water to upper tidal zones, and even in upland situations. No one

knows how many shipwrecks exist. Archaeologists estimate more

than 1,000 shipwrecks lie on state-owned aquatic lands. The

earliest known shipwrecks that might be found, include the

Russian brig, St. Nicholai, which beached near the present

Quileute Reservation in 1808, and a Japanese junk, the Hojun

Maru, which wrecked on the Washington coast near Ozette in

1834. The remains of the famous clipper ship, Glory of the Seas,

was recently investigated. It rests in the Seattle Harbor area in

West Seattle. In 1991, two Native American dugout canoes were

recovered from the bottom of Angle Lake near SeaTac Airport.

Artifacts

Smaller objects found under water include prehistoric stone and

historic metal anchors. Prehistoric

fishing hooks and stone net anchors and

weights used to sink fishing lines and

nets are found in marine and freshwater

environments. These are either grooved

or perforated stones, or they may

simply be unmodified round or oval

rocks wrapped with cherry bark.

Credit: M. L. Stilson

46

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Underwater Archaeology

Chapter 7

Bridges

The best example of bridge remains found underwater is the old

Tacoma Narrows Bridge, “Galloping Gertie,” which collapsed

into the dark waters of the Tacoma Narrows in 1940 during a

windstorm. The site has been placed on the national Register of

Historic Places. Many other bridge remnants many exist.

Railroad Cars and Locomotives

Locomotives and railroad cars slide into the water while being

transported on barges or slip off trestles or bridges while working

over water. Several railroad cars are known to be at the bottom of

Lake Washington. A steam locomotive lost ca. 1910 sits at the

bottom of Lake Stevens in Snohomish County.

Aircraft

Many planes have been lost off the coast or in the state’s lakes and

rivers. The bottom of Lake Washington next to the Sand Point

Naval Air Station is littered with aircraft.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

47

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

48

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Cultural Resources

Intentionally Placed

In or Under Water

Canoe Runs

Native Americans removed

boulders and cobbles from sub-

and intertidal pathways to allow

canoes to reach shore without

damage. Such canoe runs can be

seen at the Ozette site and at

DNR’s Hat Island and Cypress

Island Natural Resource

Conservation Areas. They are

usually located at major village

sites where beaches are strewn

with rocks and boulders.

Petroglyphs and Pictographs

Almost all known petroglyphs and pictographs in Washington

are found along the shore, many in the intertidal area. There is a

southern Puget Sound petroglyph complex characterized by faces

and designs on beach boulders. They seem to be related to village

sites and may mark village territorial boundaries. Northern Puget

Sound petroglyphs are also found on beach boulders.

Canoe run at Doe Island State Park. Credit:

Dan Meatte, Washington State Parks

Underwater Archaeology

Chapter 7

Fish Weirs and Traps

Low stone walls or lines of

wooden posts and/or

stakes used to trap fish are

known as fish traps or

weirs. These are located at

or near the mouths of large

rivers and streams, across

small shallow lagoons,

across the heads of shallow

coves, or along open

shorelines. Wooden fish traps were commonly used with netting

or mats. A preserved fish weir was discovered and excavated in

1970 at the mouth of Wapato Creek in the Blair Waterway in

Tacoma.

Fish weir on the Puyallup River, circa 1880. Credit:

State Capitol Museum, a division of the Washington

State Historical Societ

y

Reef Net Anchors

Reef net fishing was the most important economic activity of the

tribes in Whatcom and San Juan counties. Large rocks were used

to anchor an elaborate net system designed to simulate an

underwater reef to funnel salmon to waiting canoes.

Concentrations of reef net anchor stones have been mapped at

Legoe Bay on Lummi Island and at Point Roberts.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

49

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

Reef Net Illustration. Credit: Mark Macleod, Department of Natural Resources

Trash Dumps

People dump trash in low spots. Often the lowest spot is in the

water. Consequently, trash ends up under water. This has

exciting implications because normally perishable materials such

as basketry and wood are preserved underwater. Examples of

prehistoric trash dumps with preserved materials include the

50

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Underwater Archaeology

Chapter 7

3,000-year-old Hoko River wet site in Clallam County, the 2,000-

year-old Biderbost site in Snohomish County, and the 1,000-year-

old Munk Creek wet site in Skagit County.

Historic trash dumps often occur off the end of piers and in low

areas along the coast near historic occupations. These may

include bottle dumps, can dumps, discarded building materials,

generalized trash dumps, ballast, etc. Examples are known from

the Columbia River near the Fort Vancouver dock with artifacts

dating from the 1840s to WWII. Archaeologists consider trash

dumps as part of the associated upland sites.

Piers, Wharves, Docks, Bridges

The remnants of piers, wharves, or docks may be found under

water. Associated features may include wooden cribbings filled

with rocks which were used in dock construction.

The remnants of bridge abutments or supports may be found

under water typically near current or historic transportation

routes.

Dams

Splash dams were built to store water in order to float logs to the

booming grounds. Evidence of splash, hydroelectric, water

diversion and other dams may be found under water.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

51

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

Placer Mines

A placer is a glacial or alluvial deposit that contains eroded

particles of valuable minerals. Placer mines are places where

miners wash these deposits to recover valuable minerals, usually

aggrading sections of river beds. Some placer mines worked by

Chinese immigrants are on the middle Columbia River.

Marine Railways

Marine railways are track systems used to haul boats in and out

of the water and are associated with shipyards. A marine railway

on Bainbridge Island extends 500 feet into Eagle Harbor. Gig

Harbor has an active historic marine railway.

Inundated Sites

Inundated sites include prehistoric villages, campsites, and

locations of historic forts, homesteads, towns and waterfronts.

Many sites in Washington are under water behind dams. For

example, Fort Colville, Fort Okanogan and the Kettle Falls

prehistoric fishing sites are now inundated by reservoirs. In

addition, many western Washington sites have been covered or

destroyed by a worldwide rise in sea levels.

Between 13,000 and 15,000 years ago, the Puget Sound basin was

52

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Underwater Archaeology

Chapter 7

crushed beneath glacial ice. The ice was a mile thick at

Bellingham, 3,200 feet thick at Seattle, and 1,000+ feet thick at

Olympia. The glacier began melting and rapidly retreating about

14,000 years ago.

Water from the melting ice caused a rise in sea level. At the same

time, the earth’s crust, released from the weight of the ice, began

to rebound. The rebound was completed 12,000 years ago in

southern Puget Sound and 6,500 years ago in the northern part of

the state. However, the glaciers continued to melt and sea level to

rise. Sea level is still rising at a rate of more than a foot per

century in Tacoma and more than two inches a century in the San

Juan Islands. The rise in sea level also affects lakes and the lower

portions of rivers.

The rising levels of sea, rivers, and lakes have covered older

villages but not locations where resources were collected and

processed at some distance form the shore. These include

exploitation locations -- animal kill sites, quarries, plant-gathering

places, stone working workshops -- which were located away

from coastlines. Historically known Northwest Coast villages

were usually 5 to 20 feet above the high water mark, near the

mouths of rivers, at the meeting of waterways, or on sheltered

bays or inlets. Older sites in these locations have been destroyed

by wave action or are now under water.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

53

Along Washington coastlines, there are no definitely dated village

or habitation sites older than 4,300 years. In British Columbia,

there are numerous coastal habitation sites with dates as old as

Chapter 6 Historic Archaeology

10,200 years ago The Canadian sites are still above water because

rebound continued later due to the greater weight and later

retreat of glaciers in the area. There are progressively older

radiocarbon dates from marine coastal sites from southern Puget

Sound to the central coast of British Columbia. These dates

indicate when sea level rise overcame post glacial rebound and

not when initial human occupation began.

Many areas in the state have conditions that could preserve sites

under water. These conditions include gently topography,

reduced wave action due to limited reaches, and rapid

inundation.

Currently, only a few sites are known to be inundated as a result

of sea level rise. The West Point site in Seattle and the shell

midden at British Camp on San Juan Island extend below current

sea level. There is a possible submerged village at Felida Morrage

and in Lake Vancouver in Clark County. As more work is done

under water, more sites will be discovered

.

54

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

W

hat You Can Do

Chapter 8

What You Can Do

A

rchaeological sites are protected by state law on both

public and private lands. The Archaeological Sites and

Resources Act (ASRA) (RCW 27.53) proclaims that

archaeological resources in, on, or under state-owned land are the

property of the state. These resources are also protected by the

Public Lands Act (RCW 79.01) which states that a trespasser who

disturbs any “valuable materials” is guilty of larceny. A person

leasing public land may be guilty of a misdemeanor if the

disturbance is not expressly authorized.

On private lands, ASRA states that a permit is required before

knowingly disturbing any historic or prehistoric archaeological

resource or site on private or public land. The property owner or

manager must agree to the issuance of the permit. ASRA protects

archaeological sites, historic shipwrecks and submerged aircraft

from disturbance and loss. The Indian Graves and Records Act

(RCW 27.44) protects Native American burials, petroglyphs and

pictographs from intentional disturbance. These laws are

included in the Appendix.

Provisions in other statutes direct agencies to protect cultural

resources. Apart from the statutory requirments, many agencies

have developed policies addressing how archaeological site

information should be used for planning and development.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

55

56

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Chapter 8 What You Can Do

To carry out the above laws, field personnel should become

familiar with the following topics.

Theft and Vandalism

Theft and vandalism of cultural resources on state lands are

constant problems. Archaeological sites are fragile and

nonrenewable and, unlike many natural resources, archaeological

sites can not be restored or repaired. The damage caused by theft

or vandalism includes the costs of filling in the holes as well as

scientific, historic, and spiritual losses.

Vandalism at Horsethief Lake state Park. Credit: Office of Archaeology & Historic

Preservation.

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

57

W

hat You Can Do

Chapter 8

Scene of a Crime?

Archaeological sites are fragile and

subject to vandalism. Sites on all

lands in this state are protected by

law from looting, vandalism, and

theft. However, vandalism is a

common problem and in your land

management duties you may

happen upon a site that has been

vandalized.

s

erve

e

or modern trash left

y the looters.

o these three things:

e area.

When you come upon a site that ha

been vandalized, you will obs

freshly dug holes, disturbed

vegetation, and flakes, bones and

fire-cracked rock discarded by th

vandals. You may also observe

shovels, screens

b

D

1. Be observant.

Note any

individuals or vehicles in th

Note all the details of your

surroundin

g

environment, time, and

onditions. Take photographs.

cure

e site area before you leave.

r

c

2. Do not disturb anything.

Remember this is a crime scene.

Footprints, fingerprints, and the

physical evidence of the looter’s

excavation can yield clues and the

evidence in a criminal case. Se

th

3. Get help immediately.

Contact

your cultural resource coordinato

and law enforcement personnel.

Plan carefully your next steps in

assessin

g

dama

g

e, workin

g

with

enforcement, archae

Artifacts have a market value and

are seen by some as collectable art.

Theft is not limited to artifacts.

Entire panels of pictographs and

petroglyphs have been blasted

from cliff faces and removed from

public lands. Historic submerged

aircraft and preserved dugout

canoes have been removed from

lakes in Washington.

Professional archaeologists do not

approve of the personal acquisition

of artifacts or their sale. They stress

the protection of sites and the

curation of artifacts from public

land for the public good.

An archaeological site that has been

looted or vandalized is a crime

scene.

Promoting an Ethic of

Stewardship

We encourage you, as public

employees, to promote an ethic of

stewardship for archaeological

resources. Think of archaeological

sites as a collection of rare books

law

ologists and

bl l l ff

Chapter 8 What You Can Do

that are held in public trust for all to learn from and appreciate,

but not to damage. In your daily contact with the public please

help to instill a sense of respect and appreciation of these

ancestral places.

Educating the Public

The archaeological resources of Washington can provide a fuller

understanding of our history and our environment. In your daily

contact with the public, you can encourage respect for these

reminders of our common past, which will lead to their

protection.

We encourage you to learn about the archaeological resources on

the lands you manage. The attached reading list offers a variety

of archaeological topics. You may also want to participate in any

of the annual archaeological events such as Washington

Archaeology Week or discuss developing a project with the

person in your agency overseeing cultural resources.

Archaeological sites play a vital role in interpreting the past.

Seeing the physical products of past human labor or visiting the

location of important historic events brings us in direct contact

with the past.

58

A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology Revised April, 2003

Folks Who Can Help You

Chapter 9

Folks Who Can Help You

P

rotecting archaeological sites with their wealth of

knowledge and artifacts is an important job. Cultural

resources found on State lands are protected by several

state laws and, in some cases, federal law. These laws are

reproduced in the back of this book in the Appendix.

Your Agency Contacts

For general information about cultural resources in Washington

State, you can contact the Office of Archaeology and Historic

Preservation in Olympia, Washington. This office is responsible

for comprehensive historic preservation planning and maintains

records on more than 100,000 historic and prehistoric properties

recorded in Washington State.

Office of Archaeology & Historic Preservation

Rob Whitlam

State Archaeologist

Office of Archaeology & Historic Preservation

111 21st Ave SW

Olympia, WA 998504

(360) 753-4405

Revised April, 2003 A Field Guide to Washington State Archaeology

59

Chapter 9 Folks Who Can Help You

Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission

For general information about cultural resources or to report an

unanticipated discovery on Washington State Parks lands contact:

Daniel Meatte

State Parks Archaeologist

7150 Cleanwater Lane

P.O. Box 42668