Guidelines for Educators

MAURICE J. ELIAS

JOSEPH E. ZINS

ROGER P. WEISSBERG

KARIN S. FREY

MARK T. GREENBERG

NORRIS M. HAYNES

RACHAEL KESSLER

MARY E. SCHWAB-STONE

TIMOTHY P. SHRIVER

promoting

social

and

emotional

learning

ASSOCIATION FOR SUPERVISION AND CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

ALEXANDRIA,VIRGINIA USA

Education

$22.95

Fostering knowledgeable, respon-

sible, and caring students is one

of the most urgent challenges fac-

ing schools, families, and commu-

nities as we enter the 21st century.

Promoting Social and Emotional

Learning provides sound princi-

ples for meeting this challenge.

Students today face unparal-

leled demands. In addition to

achieving academically, they

must learn to work cooperatively,

make responsible decisions about

social and health practices, resist

negative peer and media influ-

ences, contribute constructively

to their family and community,

function in an increasingly diverse society, and acquire the skills,

attitudes, and values necessary to become productive workers

and citizens. A comprehensive, integrated program of social and

emotional education can help students meet these many demands.

The authors draw upon the most recent scientific studies, the

best theories, site visits carried out around the country, and their

own extensive experiences to describe approaches to social and

emotional learning for all levels. Framing the discussion are

39 concise guidelines, as well as many field-inspired examples

for classrooms, schools, and districts. Chapters address how to

develop, implement, and evaluate effective strategies.

Educators who have programs in place will find ways to

strengthen them. Those seeking further direction will find an

abundance of approaches and ideas. Appendixes include a cur-

riculum scope for preschool through grade 12 and an extensive

list of contacts that readers may follow up for firsthand knowl-

edge about effective social and emotional learning programs.

The authors of Promoting Social and Emotional Learning are

members of the Research and Guidelines Work Group of the

Collaborative for the Advancement of Social and Emotional

Learning (CASEL).

promoting

social

and

emotional

learning

Guidelines for Educators

promoting social and emotional learning

ISBN 0-87120-288-

3

9

780871 202888

90000

ISBN 0-87120-288-3

Social & Emotional 2/16/05 10:17 AM Page 1

Guidelines for Educators

MAURICE J. ELIAS

JOSEPH E. ZINS

ROGER P. WEISSBERG

KARIN S. FREY

MARK T. GREENBERG

NORRIS M. HAYNES

RACHAEL KESSLER

MARY E. SCHWAB-STONE

TIMOTHY P. SHRIVER

promoting

social

and

emotional

learning

ASSOCIATION FOR SUPERVISION AND CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

ALEXANDRIA,VIRGINIA USA

Social & Emotional TP 2/16/05 10:19 AM Page 1

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

1250 N. Pitt Street • Alexandria, Virginia 22314-1453 USA

Tel ep hon e: 1-8 00- 933 -27 23 or 70 3-5 49- 911 0 • Fax: 703-299-8631

We b si te : ht tp ://w ww.a sc d.o rg . • E-mail: member@ascd.org

Gene R. Carter,

Executive Director

Michelle Terry,

Assistant Executive Director, Program Development

Ronald S. Brandt,

Assistant Executive Director

Nancy Modrak,

Director, Publishing

John O’Neil,

Acquisitions Editor

Julie Houtz,

Managing Editor of Books

Jo Ann Irick Jones,

Senior Associate Editor

Karen Peck,

Copy Editor

Gary Bloom,

Director, Editorial, Design, and Production Services

Karen Monaco,

Senior Designer

Tra cey A. S mit h,

Production Manager

Dina Murray,

Production Assistant

Val er ie S pr ag ue ,

Desktop Publisher

Copyright © 1997 by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. All

rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any informa-

tion storage and retrieval system, without permission from ASCD. Readers who wish to

duplicate material copyrighted by ASCD may do so for a small fee by contacting the Copy-

right Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Dr., Danvers, MA 01923, USA (phone: 508-750-8400;

fax: 508-750-4470). ASCD has authorized the CCC to collect such fees on its behalf. Requests

to reprint rather than photocopy should be directed to ASCD’s permissions office at (703)

549-9110.

ASCD publications present a variety of viewpoints. The views expressed or implied in this

book should not be interpreted as official positions of the Association.

Printed in the United States of America.

e-books ($22.95): netLibrary ISBN 0-87120-571-8 • ebrary ISBN 1-4166-0260-7 • Retail PDF ISBN1-4166-0261-5

September 1997 member book (pcr). ASCD Premium, Comprehensive, and Regular mem-

bers periodically receive ASCD books as part of their membership benefits. No. FY98-1.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Promoting social and emotional learning : guidelines for educators /

Maurice J. Elias ... [et al.].

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87120-288-3 (pbk.)

1. Affective education—United States. 2. Social skills—Study

and teaching—United States. 3. Emotions—Study and teaching—

United States. I. Elias, Maurice J.

LB1072.P76 1997

370.15’3—dc21 97-21198

CIP

01 00 99 98 97 5 4 3 2 1

™

Promoting Social and Emotional Learning:

Guidelines for Educators

Acknowledgments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v

Preface . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vii

1. The Need for Social and Emotional Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

2. Reflecting on Your Current Practices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

3. How Does Social and Emotional Education Fit in Schools? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

4. Developing Social and Emotional Skills in Classrooms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

5. Creating the Context for Social and Emotional Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75

6. Introducing and Sustaining Social and Emotional Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

7. Evaluating the Success of Social and Emotional Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

8. Moving Forward: Assessing Strengths, Priorities, and Next Steps . . . . . . . . . . 117

Epilogue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127

Appendix A: Curriculum Scope for Different Age Groups . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

Appendix B: Guidelines for Social and Emotional Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139

Appendix C: Program Descriptions, Contacts, and Site Visit Information . . . . . . 143

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153

About the Authors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

Acknowledgments

A

BOOK THAT HAS NUMEROUS AUTHORS, INCORPO-

rates on-site visits around the United States, and is

based on action research carried out, collectively,

over several decades at dozens of sites and involv-

ing hundreds of thousands of students and thou-

sands of educators easily could have an

acknowledgments section reminiscent of the cred-

its for a Cecil B. DeMille movie. Indeed, each of the

authors of this book has mentors, assistants, and

collaborators.

What we will do is thank those individuals

whose efforts literally made this book possible.

Foremost among these are the Founders and Lead-

ership Team of the Collaborative for the Advance-

ment of Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL):

Maurice Elias, Eileen Rockefeller Growald, Daniel

Goleman, Tom Gullotta, David Sluyter, Linda Lan-

tieri, Mary Schwab-Stone, and Tim Shriver. The

core support staff members of CASEL’s central of-

fice, originally based at Yale (Peggy Nygre n, Char-

lene Voyce) and now housed at the University of

Illinois at Chicago (Sharmistha Bose, Bella Giller,

Carol Bartels Kuster, May Stern) have provided pa-

tient, diligent, and skilled logistical and conceptual

assistance.

We thank all those who consented to be part of

our on-site visits and who provided information

about their programs prior to our deadlines. Con-

tact information for these programs is provided in

Appendix C. Most probably, our on-site visit team

now has more details about more social and emo-

tional learning programs than anyone else. Linda

Bruene-Butler and Lisa Blum conducted most of

the visits, and did so expertly. They also did an out-

standing job organizing the many tapes and writ-

ten materials they obtained. Zephryn Conte also

conducted two on-site visits, and an ace team of

Rutgers undergraduates helped with the tran-

scripts: Debi Ribatsky, Allison Larger, Joanne

Mucerino, and Laura Green. Tom Schuyler, a re-

tired school principal with more than two decades

of experience working with SEL programs, pro-

vided a generous dose of wisdom. Thanks also to

Bob Hanson of National Professional Resources,

who donated copies of videos that depicted pro-

grams we were unable to visit.

Financial support for CASEL from the Fetzer

Institute, the Surdna Foundation, and the Univer-

sity of Illinois at Chicago, among others, facilitated

our conference calls and meetings. Fetzer also pro-

vided the funding for the on-site visits. The Fetzer

Institute also hosted the conference at which mem-

bers of CASEL met with Ron Brandt of ASCD and

John Conyers, Betty Davis, and Harriet Arnold,

long-time ASCD leaders who served as a kind of fo-

cus group discussing this book. Their valuable sug-

gestions helped to shape and ground our thinking.

ASCD has been a true partner in this project.

In addition to the individuals listed above, Mikki

Terry, Agnes Crawford, and Sally Chapman pro-

v

vided valuable support as they thought about the

book’s follow-up with professional development

institutes and curricular and video projects. Nancy

Modrak, John O’Neil, and Julie Houtz have been

the shepherds of the manuscript, giving gentle and

helpful guidance. The person who has been most

directly involved is Jo Ann Irick Jones, and we can-

not say enough about her tireless work, her tremen-

dous grasp of the basic concept of the manuscript,

and her creative ideas about how to convey those

ideas clearly, both in words and in layout. We also

salute the many others who provided editorial and

production wizardry at ASCD. (What a book

cover!) We look forward to a long ASCD-CASEL

collaboration in the interests of children and the

betterment of schools.

We also want to thank the children, parents,

and educators with whom we have worked, and

who taught us a great deal. We consider ourselves

privileged to be working in the schools, to be able

to watch and learn and contribute to this most criti-

cal aspect of children’s upbringing. The belief that

SEL is the missing piece in children’s academic and

interpersonal success and sound health has fueled

our continuing efforts. We are honored to bring

this work to a vast education audience through the

auspices of ASCD.

Finally, we wish to thank our families. They

have supported our action research, our writing,

our meetings, and all of the work related to bring-

ing this book to its completion. Three families—

those of Maurice Elias, Joe Zins, and Roger

Wei ssbe rg— bore p arti cul ar b urdens du ri ng Dece m-

ber 1996 and January 1997, as the struggle to make

the publication deadline and pull together vast

amounts of materials in a coherent manner grew

more intense, and time grew short. Their patience

and support show their great reservoirs of social

and emotional skills, for which we are grateful.

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

vi

Preface

D

URING THE PAST FEW DECADES, SCHOOLS HAVE BEEN

inundated with well-intentioned positive youth de-

velopment efforts to promote students’ compe-

tence and to prevent social and health problems.

Relevant topics have included initiatives in the fol-

lowing areas:

•

AIDS education

•

law-related education

•

career education

•

moral education

•

character education

•

multicultural

education

•

civic education

•

nutrition education

•

delinquency prevention

•

physical injury

prevention

•

dropout prevention

•

positive peer bonding

•

drug education

•

sex education

•

family-life education

•

truancy prevention

•

health education

•

violence prevention

It’s enough to make an educator’s (not to men-

tion a student’s) head spin!

Fostering knowledgeable, responsible, and car-

ing students is an important priority for our na-

tion’s schools, families, and communities. Yet

today’s children face unparalleled demands in

their everyday lives. They must learn to achieve

academically, work cooperatively, make responsi-

ble decisions about social and health practices, re-

sist negative peer and media influences, contribute

constructively to their family and community, inter-

act effectively in an increasingly diverse society,

and acquire the skills, attitudes, and values neces-

sary to become productive workers and citizens.

Although most people agree that it is impor-

tant for schools to provide education that produces

knowledgeable, responsible, and caring students,

there is disagreement about how these outcomes

can be best achieved. Unfortunately, in their efforts

to respond to the needs of students, many schools

have adopted information-oriented, single-issue

programs that lack research evidence to support

their effectiveness. In this book, we draw upon re-

cent scientific studies, the best theories, and the

successful efforts of educators across the nation to

provide guidelines to help school administrators,

teachers, and pupil-services personnel design, im-

plement, and evaluate comprehensive, coordinated

programming to enhance the social and emotional

development of children from preschool through

high school. A growing body of evidence indicates

that systematic, ongoing education to enhance the

social and emotional skills of children provides a

firm foundation for their successful cognitive and

behavioral development.

This book was coauthored by members of the

Research and Guidelines Committee of the Col-

laborative for the Advancement of Social and Emo-

tional Learning (CASEL). As such, it truly

represents our collaborative efforts and demon-

strates how such a joint approach can greatly en-

hance what any one of us could have

vii

accomplished alone. The coauthors include re-

searchers, practitioners, and trainers, and the final

product represents these different perspectives.

CASEL was founded in 1994 to support

schools and families in their efforts to educate

knowledgeable, responsible, and caring young peo-

ple who will become productive workers and con-

tributing citizens in the 21st century. As we are

painfully aware, rates of drug use, violence and de-

linquency, damaging health practices, and poor

school performance are unacceptably high among

youth in spite of several decades of heightened

public awareness about these issues. CASEL’s pur-

pose is to provide a forum for the exchange of vi-

sion, expertise, and ideas regarding effective

solutions to promote positive social, emotional,

and behavioral development.

CASEL is composed of an international net-

work of educators, scientists, and concerned citi-

zens. Its purpose is to encourage and support the

creation of safe, caring learning environments that

build social, cognitive, and emotional skills. We

have the following primary goals:

1. To increase the awareness of educators, train-

ers of school-based professionals, the scientific

community, policymakers, and the public about

the need for, and the effects of, systematic efforts to

promote the social and emotional learning (SEL) of

children and adolescents.

2. To facilitate the implementation, ongoing

evaluation, and refinement of comprehensive so-

cial and emotional education programs, beginning

in preschool and continuing through high school.

Through research, scholarship, networking,

and sharing current information we seek to foster

the effective implementation of theoretically based

and scientifically sound social and emotional edu-

cation programs and strategies. Founded in the be-

lief that a collaborative model benefiting from the

collective wisdom, experience, and contributions

of scientists and educators is the most effective and

promising path to developing beneficial programs,

CASEL helps to identify and coordinate the best

school, family, and community practices across di-

verse prevention, health-promotion, and positive

youth development efforts.

CASEL strives to foster the development of

standards for SEL to assure that well-designed pro-

grams are effectively and ethically implemented by

competent educators who are well selected and

well trained. It seeks to increase opportunities for

educators in all phases of their careers to learn

about programs and receive training in scientifi-

cally tested practices that promote social and emo-

tional development. It educates public

policymakers and government administrators

about approaches that advance SEL. CASEL be-

lieves that the most beneficial SEL efforts are estab-

lished through school-family partnerships where

teachers and parents participate actively in pro-

gram selection, design, implementation, evalu-

ation, and improvement.

The purpose of this book is to address the cru-

cial need among educators for a straightforward

and practical guide to establish quality social and

emotional education programming. These guide-

lines highlight implementation practices that effec-

tively promote SEL among children. As one follow-

up to this book, CASEL is systematically and com-

prehensively conducting an empirical review to

evaluate the quality of SEL programs according to

criteria that will help educators and parents make

informed choices about high-quality curriculums.

Results from this review will be available in 1998.

CASEL currently has four active working com-

mittees: Research and Guidelines, Education and

Training, Communication, and Networking. They

are working to create a library and resource center

on social and emotional education, to develop tech-

nologies that will increase educator access to infor-

mation about social and emotional education, to

conduct diverse research projects to understand

and improve processes through which the best SEL

practices are implemented and institutionalized,

and to forge collaborative relationships with or-

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

viii

ganizations and policymakers committed to en-

couraging families, schools, and communities that

foster knowledgeable, responsible, and caring stu-

dents. These projects illustrate our mission to pro-

mote the exchange of ideas and resources about

SEL and to provide educators, parents, practitio-

ners, and researchers with the best of available

practices and information.

In keeping with our belief in the importance of

collaboration, CASEL invites you, the reader, to

share information about your own program efforts,

and to request information about current develop-

ments and effective practices around the world.

CASEL’s Central Office can be reached at:

CASEL

Department of Psychology (M/C 285)

The University of Illinois at Chicago

1007 W. Harrison St.

Chicago, IL 60607-7137

We also invite you to visit CASEL’s web page

to learn what’s new at CASEL. The web site con-

tains general information about CASEL projects

and events, and information about state-of-the-art

social and emotional educational practices. We

regularly update our web site, so we recommend

that you contact it monthly for current informa-

tion. Our address is:

http://www.cfapress.org/casel/casel.html

A Study Guide for this book is available on

ASCD’s Web at

http://www.ascd.org/StudyGuide/

or by calling ASCD’s 24-hour Fax-on-Demand serv-

ice (from your fax or phone) at 800-405-0342 or 703-

299-8232.

Finally, we have organized a listserv for indi-

viduals interested in the social and emotional de-

velopment of young people. Members will be able

to communicate about important issues in social

and emotional education, post questions, and dis-

cuss their own work in this area. We believe the list-

serv will be a useful tool for sharing ideas and

information and for generating enthusiasm for

high-quality social and emotional learning. You

may subscribe for free to this listserv using the fol-

lowing steps:

1. Send an e-mail message to:

majordomo@cfapress.org

2. In the subject area, type: list

3. In the message area, type: subscribe mcasel

4. Send the message!

We look forward to collaborating with you. We

are eager to learn from you and to support your

efforts.

Roger P. Weissberg

CASEL, Executive Director

Chicago, Illinois

Timothy P. Shriver

CASEL Leadership Team, Chair

Washington, D.C.

Eileen R. Growald

CASEL Founder & Leadership Team, Vice-Chair

San Francisco, California

Preface

ix

The Need for Social and Emotional

Learning

1

I

T SOMETIMES SEEMS THAT EVERYONE WANTS TO

improve schooling in America, but each in a differ-

ent way. Some want to strengthen basic skills; oth-

ers, critical thinking. Some want to promote

citizenship or character; others want to warn

against the dangers of drugs and violence. Some

demand more from parents; others accent the role

of community. Some emphasize core values; oth-

ers, the need to respect diversity. All, however, rec-

ognize that schools play an essential role in

preparing our children to become knowledgeable,

responsible, caring adults.

Knowledgeable. Responsible. Caring. Behind

each word lies an educational challenge. For chil-

dren to become

knowledgeable

, they must be ready

and motivated to learn, and capable of integrating

new information into their lives. For children to be-

come

responsible

, they must be able to understand

risks and opportunities, and be motivated to

choose actions and behaviors that serve not only

their own interests but those of others. For children

to become

caring

, they must be able to see beyond

themselves and appreciate the concerns of others;

they must believe that to care is to be part of a com-

munity that is welcoming, nurturing, and con-

cerned about them.

The challenge of raising knowledgeable, re-

sponsible, and caring children is recognized by

nearly everyone. Few realize, however, that

each ele-

ment of this challenge can be enhanced by thoughtful,

sustained, and systematic attention to children’s social

and emotional learning (SEL).

Indeed, experience

and research show that promoting social and emo-

tional development in children is “the missing

piece” in efforts to reach the array of goals associ-

ated with improving schooling in the United

States. There is a rising tide of understanding

among educators that children’s SEL can and

should be promoted in schools (Langdon 1996). Al-

though school personnel see the importance of pro-

grams to enhance students’ social, emotional, and

physical well-being, they also regard prevention

campaigns with skepticism and frustration, be-

cause most have been introduced as disjointed

fads, or a series of “wars” against one problem or

another. Although well intentioned, these efforts

have achieved limited success due to a lack of coor-

dinated strategy (Shriver and Weissberg 1996).

Based on patterns of child development and

on prevention research, a new generation of social

and emotional development programs is being

used in thousands of schools. Today’s educators

have a renewed perspective on what common

sense always suggested: when schools attend sys-

tematically to students’ social and emotional skills,

the academic achievement of children increases,

the incidence of problem behaviors decreases, and

the quality of the relationships surrounding each

child improves. And, students become the produc-

tive, responsible, contributing members of society

1

that we all want. Perhaps the most important redis-

covery is that working in classrooms and schools

where social and emotional skills are actively pro-

moted is fun and rewarding. As we allow the hu-

manity, decency, and childishness of students (and

ourselves, to some degree) to find a legitimate

place in the learning environment, we rediscover

our reasons for becoming educators.

Thus, social and emotional education is some-

times called the missing piece, that part of the mis-

sion of the school that, while always close to the

thoughts of many teachers, somehow eluded them.

Now, the elusive has become the center, and the op-

portunities to reshape schooling are upon us.

What Is Social and Emotional

Education—And Why Is It

Important?

Social and emotional competence is the ability to

understand, manage, and express the social and

emotional aspects of one’s life in ways that enable

the successful management of life tasks such as

learning, forming relationships, solving everyday

problems, and adapting to the complex demands

of growth and development. It includes self-aware-

ness, control of impulsivity, working cooperatively,

and caring about oneself and others. Social and

emotional learning is the process through which

children and adults develop the skills, attitudes,

and values necessary to acquire social and emo-

tional competence. In

Emotional Intelligence

, Daniel

Goleman (1995) provides much evidence for social

and emotional intelligence as the complex and mul-

tifaceted ability to be effective in all the critical do-

mains of life, including school. But Goleman also

does us the favor of stating the key point simply:

“It’s a different way of being smart.”

In recent years, character education has re-

ceived a great deal of attention, including mention

in President Clinton’s 1997 State of the Union ad-

dress. You might wonder about its relationship to

social and emotional education. Without going into

a lengthy discussion of character education (see

Lickona 1991, 1993a), it is apparent that the best

character education and social and emotional edu-

cation programs share many overlapping goals.

The Character Education Partnership in Alexan-

dria, Virginia, defines character education as “the

long-term process of helping young people de-

velop good character, i.e., knowing, caring about,

and acting upon core ethical values such as fair-

ness, honesty, compassion, responsibility, and re-

spect for self and others.” Whereas many character

education programs promote a set of values and di-

rective approaches that presumably lead to respon-

sible behavior (Brick and Roffman 1993, Lickona

1993b, Lockwood 1993), social and emotional edu-

cation efforts typically have a broader focus. They

place more emphasis on active learning tech-

niques, the generalization of skills across settings,

and the development of social decision-making

and problem-solving skills that can be applied in

many situations. Moreover, social and emotional

education is targeted to help students develop the

attitudes, behaviors, and cognitions to become

“healthy and competent” overall—socially, emo-

tionally, academically, and physically—because of

the close relationship among these domains. And,

as you will see, social and emotional education has

clear outcome criteria, with specific indicators of

impact identified. In sum, both character education

and social and emotional education aspire to teach

our students to be good citizens with positive val-

ues and to interact effectively and behave construc-

tively. The challenge for educators and scientists is

to clarify the set of educational methods that most

successfully contribute to those outcomes.

The social and emotional education of children

may be provided through a variety of diverse ef-

forts such as classroom instruction, extracurricular

activities, a supportive school climate, and involve-

ment in community service. Many schools have en-

tire curriculums devoted to SEL. In classroom-

based programs, educators enhance students’ so-

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

2

cial and emotional competence through instruction

and structured learning experiences throughout

the day. For example, the New Haven, Connecti-

cut, public schools have outlined the scope of their

K–12 Social Development Project, identifying an ar-

ray of interrelated skills, attitudes, values, and do-

mains of information that lay a foundation for

constructive development and behavior (see

Figure 1.1).

The goals of New Haven’s Social Development

Project are to educate students so that they

•

Acquire a knowledge base plus a set of basic

skills, work habits, and values for a lifetime of

meaningful work.

•

Feel motivated to contribute responsibly and

ethically to their peer group, family, school, and

community.

•

Develop a sense of self-worth and feel effec-

tive as they deal with daily responsibilities and

challenges.

•

Are socially skilled and have positive rela-

tionships with peers and adults.

•

Engage in positive, safe, health-protective be-

havior practices.

To achieve these outcomes, school personnel

collaborate with parents and community members

to provide educational opportunities that (a) en-

hance children’s self-management, problem-solv-

ing, decision-making, and communication skills;

(b) inculcate prosocial values and attitudes about

self, others, and work; and (c) inform students

about health, relationships, and school and commu-

nity responsibilities. Social development activities

promote communication, participation in coopera-

tive groups, emotional self-control and appropriate

expression, and thoughtful and nonviolent prob-

lem resolution. More broadly, these skills, atti-

tudes, and values encourage a reflective, ready-to-

learn approach to all areas of life. In short, they

promote knowledge, responsibility, and caring.

Can People Succeed Without

Social and Emotional Skills?

Is it possible to attain true academic and personal

success without addressing SEL skills? The accu-

mulating evidence suggests the answer is no. Stud-

ies of effective middle schools have shown that the

common denominator among different types of

schools reporting academic success is that they

have a systematic process for promoting children’s

SEL. There are schoolwide mentoring programs,

group guidance and advisory periods, creative

modifications of traditional discipline procedures,

and structured classroom time devoted to social

and emotional skill building, group problem solv-

ing, and team building (Carnegie Council on Ado-

lescent Development 1989). Of course, they have

sound academic programs and competent teachers

and administrators, but other schools have those

features as well. It is the SEL component that distin-

guishes the effective schools.

The importance of SEL for successful academic

learning is further strengthened by new insights

from the field of neuropsychology. Many elements

of learning are relational (or, based on relation-

ships), and social and emotional skills are essential

for the successful development of thinking and

learning activities that are traditionally considered

cognitive (Brendtro, Brokenleg, and Van Bockern

1990; Perry 1996). Processes we had considered

pure “thinking” are now seen as phenomena in

which the cognitive and emotional aspects work

synergistically. Brain studies show, for example,

that memory is coded to specific events and linked

to social and emotional situations, and that the lat-

ter are integral parts of larger units of memory that

make up what we learn and retain, including what

takes place in the classroom. Under conditions of

real or imagined threat or high anxiety, there is a

loss of focus on the learning process and a reduc-

tion in task focus and flexible problem solving. It is

as if the thinking brain is taken over (or “hijacked,”

as Goleman says) by the older limbic brain. Other

The Need for Social and Emotional Learning

3

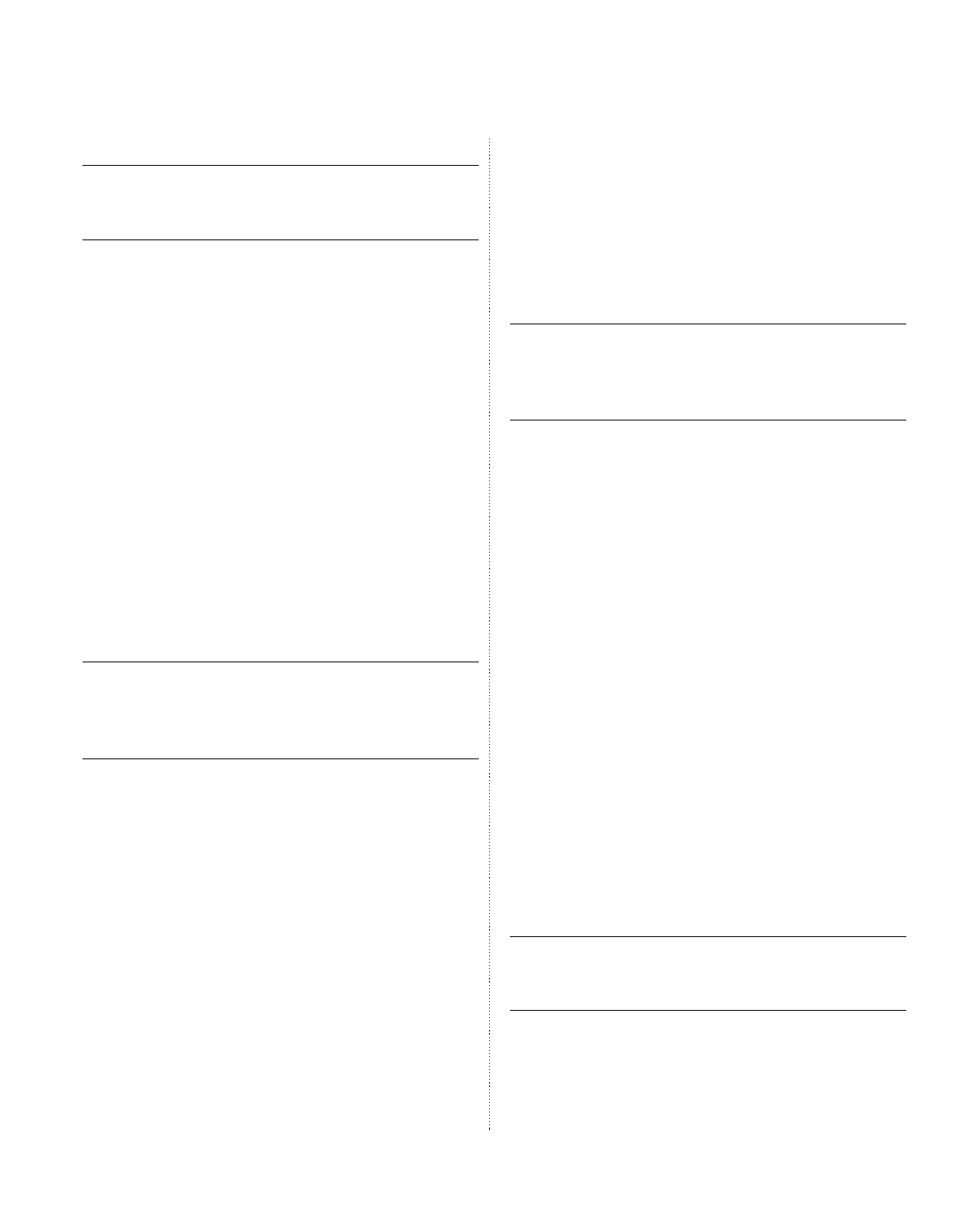

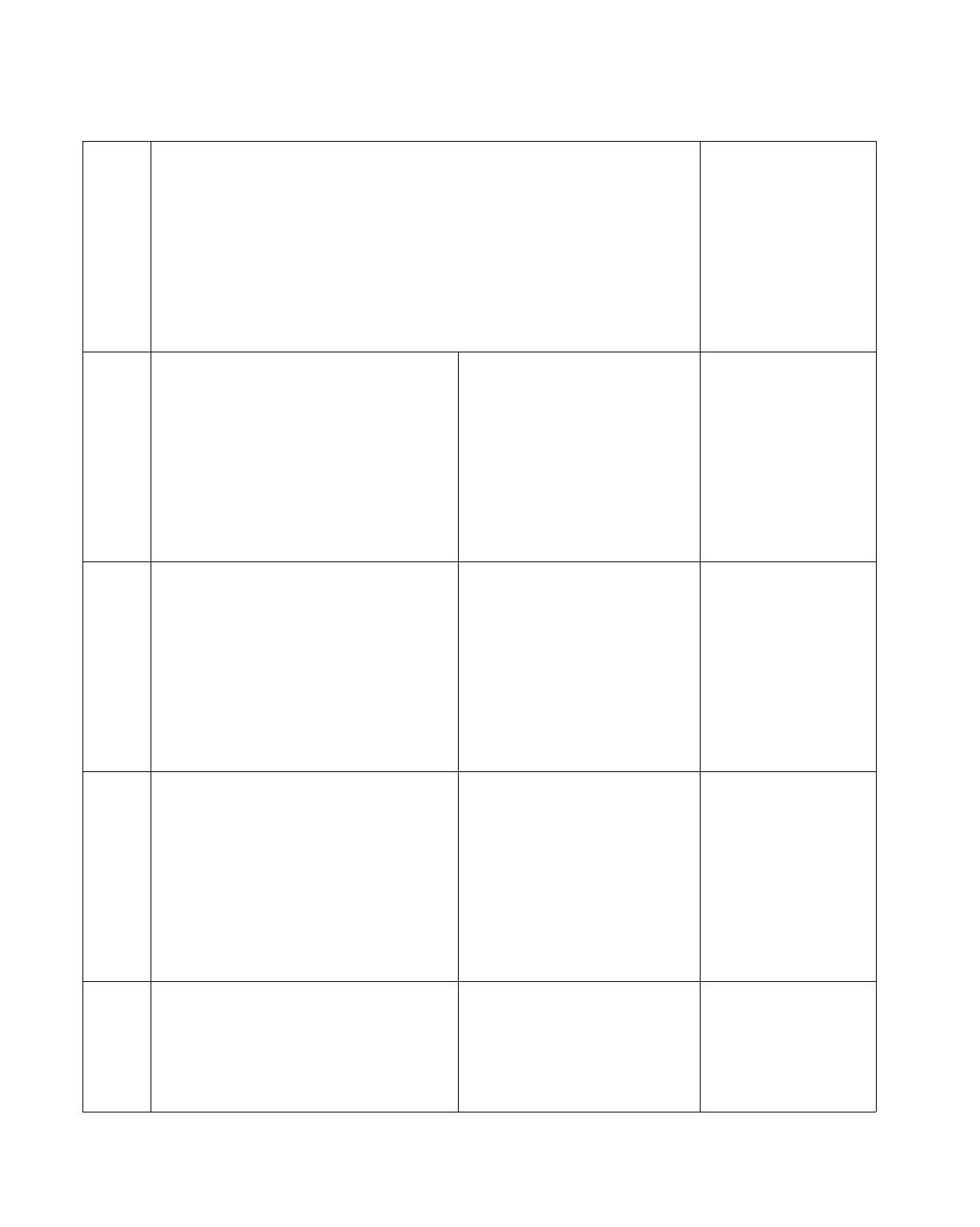

F

IGURE

1.1

N

EW

H

AVEN

S

OCIAL

D

EVELOPMENT

C

URRICULUM

S

COPE

Life Skills Curriculum Scope

Preschool through 12th grade

Skills

Self-Management

Self-monitoring

Self-control

Stress management

Persistence

Emotion-focused coping

Self-reward

Problem Solving and Decision Making

Problem recognition

Feelings awareness

Perspective taking

Realistic and adaptive goal setting

Awareness of adaptive response strategies

Alternative solution thinking

Consequential thinking

Decision making

Planning

Behavioral enactment

Communication

Understanding nonverbal communication

Sending messages

Receiving messages

Matching communication to the situation

Attitudes and Values

About Self

Self-respect

Feeling capable

Honesty

Sense of responsibility

Willingness to grow

Self-acceptance

About Others

Awareness of social norms and values—peer,

family, community, and society

Accepting individual differences

Respecting human dignity

Having concern or compassion for others

Valuing cooperation with others

Motivation to solve interpersonal problems

Motivation to contribute

About Tasks

Willingness to work hard

Motivation to solve practical problems

Motivation to solve academic problems

Recognition of the importance of education

Respect for property

Content

Self/Health

Alcohol and other drug use

Education and prevention of AIDS

and STDs

Growth and development and

teen pregnancy prevention

Nutrition

Exercise

Personal hygiene

Personal safety and first aid

Understanding personal loss

Use of leisure time

Spiritual awareness

Relationships

Understanding relationships

Multicultural awareness

Making friends

Developing positive relationships

with peers of different genders

races and ethnic groups

Bonding to prosocial peers

Understanding family life

Relating to siblings

Relating to parents

Coping with loss

Preparation for marriage and

parenting in later life

Conflict education and violence

prevention

Finding a mentor

School/Community

Attendance education and truancy

and dropout prevention

Accepting and managing

responsibility

Adaptive group participation

Realistic academic goal setting

Developing effective work habits

Making transitions

Environmental responsibility

Community involvement

Career planning

Source:

Weissberg, R.P., A.S. Jackson, and T.P. Shriver. (1993). “Promoting Positive Social Development and Health Practices in Young Ur-

ban Adolescents.” In

Social Decision Making and Life Skills Development: Guidelines for Middle School Educators

, edited by M.J. Elias,

pp. 45–77. Gaithersburg, Md.: Aspen Publications.

Copyright © 1991 by Alice Stroop Jackson and Roger P. Weissberg

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

4

emotion-related factors can be similarly distracting

(Nummela and Rosengren 1986, Perry 1996, Syl-

wester 1995).

Sylwester (1995) highlights ways in which

SEL fosters improved performance in schools (see

Figure 1.2). He points out that

we know emotion is very important to the

educative process because it drives atten-

tion, which drives learning and memory.

We’ve never really understood emotion,

however, and so don’t know how to regulate

it in school—beyond defining too much or

too little of it as misbehavior and relegating

most of it to the arts, PE, recess, and the ex-

tracurricular program. . . . By separating

emotion from logic and reason in the class-

room, we’ve simplified school management

and evaluation, but we’ve also then sepa-

rated two sides of one coin—and lost some-

thing important in the process. It’s

impossible to separate emotion from the

other important activities of life. Don’t try

(pp. 72, 75).

The basic skills of SEL are necessary for stu-

dents to be able to take full advantage of their bio-

logical equipment and social legacy and heritage.

As schools provide the conditions that allow even

the students most at risk of failure to become en-

gaged in the learning process, new possibilities

open up and new life trajectories become available

to students. We know from resilience research that

even in the worst conditions, such as decaying in-

ner cities, we still find some children emerging in

positive ways. Wherever one looks at children who

have remained in school, one will find that SEL

was provided to these children by at least one or

two caring people, often in the schools.

Social and emotional issues are also at the

heart of the problem behaviors that plague many

schools, communities, and families, sapping learn-

ing time, educators’ energy, and children’s hope

and opportunities. Effectively promoting social

and emotional competence is the key to helping

young people become more resistant to the lure of

drugs, teen pregnancy, violent gangs, truancy, and

dropping out of school. Consider, for example, the

current interest in the character education move-

ment, which follows years of attention to the vio-

lence prevention movement, the values education

movement, the citizenship education movement,

and the drug abuse education movement. All of

these movements have common objectives: to help

children acquire the skills, attitudes, values, and ex-

periences that will motivate them to resist destruc-

tive behaviors, make responsible and thoughtful

decisions, and seek out positive opportunities for

growth and learning.

Can any of these movements succeed without

teaching social and emotional skills? Clearly not.

In fact, the programs that lack such instruction are

notoriously ineffective. Among the least successful

F

IGURE

1.2

B

RAIN

R

ESEARCH

AND

S

OCIAL

AND

E

MOTIONAL

L

EARNING

Robert Sylwester outlines six areas in which

emotional and social learning must come to-

gether for the benefit of children and schools:

•

Accepting and controlling our emotions

•

Using metacognitive activities

•

Using activities that promote social interaction

•

Using activities that provide an emotional

context

•

Avoiding intense emotional stress in school

•

Recognizing the relationship between emo-

tions and health

He also points out that the multiple intelli-

gences are socially based and interrelated: “It’s

difficult to think of linguistic, musical, and inter-

personal intelligence out of the context of so-

cial and cooperative activity, and the other four

forms of intelligence are likewise principally so-

cial in normal practice.”.

Source:

Sylwester 1995, pp. 75–77, 117

The Need for Social and Emotional Learning

5

substance abuse prevention programs are those

that provide students information about the dan-

gers of illicit drug use without helping them under-

stand the social and emotional dimensions of peer

pressure, stress, coping, honesty, and consequential

thinking (Dusenbury and Falco 1997). Indeed, such

information-oriented prevention programs have

sometimes been blamed for

increases

in substance

abuse rates! The truth is, such programs have not

been found effective. But this unfortunate outcome

cannot be any more surprising than, say, the poor

performance of a car with a one-gallon gas tank.

Without adequate fuel, neither will get very far. We

cannot educate children about the reality of drugs

without preparing them for the social and emo-

tional struggles they will confront when exposed

to media images about drug use and to opportuni-

ties to use drugs.

Some existing prevention efforts do incorpo-

rate skills for refusing drugs and other entice-

ments, skills for resisting peer pressure, ways to

focus on one’s goals, techniques for time manage-

ment, and steps for making thoughtful, calm deci-

sions—all of which are important skills that

prevent problem behaviors. But typically these pre-

vention efforts fail to address the missing piece:

feelings that confuse children so that they cannot

and do not learn effectively. Children’s emotions

must be recognized and their importance for learn-

ing accepted. By meeting the challenges implicit in

accomplishing this goal, we can clear the pathways

to competence.

The Significance of Caring

Can children become caring members of a school

community without attention to the social and

emotional dimensions of their lives? Again, the an-

swer seems obvious. Caring is central to the shap-

ing of relationships that are meaningful,

supportive, rewarding, and productive. Caring

happens when children sense that the adults in

their lives think they are important and when they

understand that they will be accepted and re-

spected, regardless of any particular talents they

have. Caring is a product of a community that

deems all of its members to be important, believes

everyone has something to contribute, and ac-

knowledges that everyone counts.

We work better when we care and when we

are cared about, and so do students. Caring is a

spoken or an unspoken part of every interaction

that takes place in classrooms, lunchrooms, hall-

ways, and playgrounds. Children are emotionally

attuned to be on the lookout for caring, or a lack

thereof, and they seek out and thrive in places

where it is present. The more emotionally troubled

the student, the more attuned he or she is to caring

in the school environment.

At-risk kids are most vulnerable for growing

up without caring. It is caring that plays a critical

role in overcoming the narrowness, selfishness,

and mean-spiritedness that too many of our chil-

dren cannot avoid being exposed to, and that re-

places these attitudes with a culture of welcome.

Caring, the value that most Americans seem to

agree is most necessary in adult life, is rooted

in the social and emotional development of

childhood.

Social and Emotional Skills Matter

Beyond the Classroom

If the goal of helping children become knowledge-

able, responsible, and caring is a central element of

social and emotional development and schooling,

then institutions other than schools should be inter-

ested in fostering these qualities as well. Ironically,

social and emotional skills, attitudes, and values

have been embraced most enthusiastically in the

boardrooms of corporate America. Moreover, busi-

nesses of all sizes have come to realize that

produc-

tivity depends on a work force that is socially and

emotionally competent.

Workers who are capable of

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

6

managing their social and emotional interactions

with colleagues and customers, as well as their

own emotional health, are more effective at im-

proving the bottom line and at making workplaces

more efficient. In light of new knowledge about so-

cial and emotional development, captains of indus-

try and the moms and pops of neighborhood

businesses are rushing to update their techniques

for selecting and training workers, organizing the

work environment, and developing managers and

leaders. They understand that social and emotional

competence may be more important than all of the

institutions attended, degrees earned, test scores

obtained, and even technical knowledge gained.

More focus is being placed on problem solving, re-

flection, perceptive thinking, self-direction, and

motivation for lifelong learning—characteristics

that are useful no matter what the job (Adams and

Hamm 1994). To illustrate this point, Figure 1.3 de-

scribes the skills that employers believe teenagers

should have.

Goleman (1995) provides insights into this

shift of priorities. In contrast to other skills, em-

ployers believe their workers show the greatest

shortage in the social and emotional areas, and

they recognize that businesses are ill-equipped to

train employees in these areas. Thus, young people

must be prepared for the new workplace with

more than the technical and content-specific skills

of traditional schooling. Business has made it clear

that new qualities are being sought in employees.

The accent is on being a flexible thinker, a quick

problem solver, and a team player capable of help-

ing the organization adjust to ever-changing mar-

kets. Employees are expected to have the basic

knowledge necessary to manage the task at hand,

but they are also expected to be able to learn

quickly and regularly on the job, adapt to new de-

mands and environments, collaborate with others,

motivate colleagues, and get along with a variety

of people in different situations. In other words,

working smarter is now the complement to work-

ing harder.

Increasingly, competence in recognizing and

managing emotions and social relationships is seen

as a key ability for success in the workplace and for

effective leadership. Moreover, both health profes-

sionals and workplace managers acknowledge that

the social and emotional status of an individual

may be a substantial factor in determining the per-

son’s capacity to resist disease and even to recover

from illness (and we suspect school nurses would

heartily agree). As educators increasingly recog-

nize the critical role that social and emotional skills

play in fostering productive, healthy workers, state

departments of education have established core

curriculum content standards emphasizing their

development (see Figure 1.4).

F

IGURE

1.3

W

HAT

E

MPLOYERS

W

ANT

FOR

T

EENS

:

1980

S

U.S. D

EPARTMENT

OF

L

ABOR

,

E

MPLOYMENT

,

AND

T

RAINING

A

DMINISTRATION

R

ESEARCH

P

ROJECT

1. L e a r n i n g - t o - l e a r n s k i l l s

2. Listening and oral communication

3. Adaptability: creative thinking and problem

solving, especially in response to barriers/

obstacles

4. Personal management: self-esteem, goal-

setting/self-motivation, personal career develop-

ment/goals—pride in work accomplished

5. Group effectiveness: interpersonal skills, ne-

gotiation, teamwork

6. Organizational effectiveness and leadership:

making a contribution

7. Competence in reading, writing, and compu-

tation

The report notes that the seventh skill, while es-

sential, is no longer sufficient for workplace

competence.

The Need for Social and Emotional Learning

7

Issues of SEL have also influenced political

writers on democracy and citizenship (Boyer 1990,

Parker 1996). Responsible members of a democ-

racy are constantly challenged by changes in tech-

nology, communication, and cultural

demographics and must filter and integrate large

amounts of information from increasingly sophisti-

cated political operatives, electorate pulse-takers,

and opinion shapers. Parker asserts that civil com-

petencies cannot fully develop with family influ-

ence only, and he calls for civic education in

schools and other settings where children learn

and grow. The skills of reflective problem solving

and decision making, managing one’s emotions,

taking a variety of perspectives, and sustaining en-

ergy and attention toward focused goals are

among many that are called upon at every level,

from pulling the lever in the voting booth to enact-

ing laws in state legislatures, making judicial deci-

sions, and issuing directives from the Oval Office.

And, it takes a similar array of skills to successfully

run a classroom, school, or school district.

How Have Educators Responded to

Calls for SEL?

For educators in U.S. schools, the response to the

renewed awareness about the importance of social

and emotional development has been mixed. In

some circles, this task is still seen as solely the re-

sponsibility of families. The reasoning sounds tra-

ditional: the family should be the place where the

child learns to understand, control, and work

through emotions; social and emotional issues are

essentially private concerns that should be left at

the door when a child enters a school to go about

the business of acquiring academic knowledge.

This thinking has an appealing nostalgia: the

school, like the workplace, was always an environ-

ment where the agenda was not supposed to be in-

terpersonal relationships, but the task at hand.

There is learning to be done—what does this have

to do with “feelings”?

On the other hand, educators have always un-

derstood on a general level the implications of so-

cial and emotional issues for children’s learning

and development. The best teachers have always

been adept at helping children develop socially

and emotionally, and many teachers are naturally

gifted at promoting the skills, attitudes, and values

of competent social and emotional development. It

is easy for most people to recall a teacher who

made students feel capable of managing the chal-

lenges of learning, or who ran the classroom so

F

IGURE

1.4

E

XCERPTS

F

ROM

C

ORE

C

URRICULUM

C

ONTENT

S

TANDARDS

FOR

N

EW

J

ERSEY

(M

AY

1996)

Cross-Content Workplace Readiness

Standards

•

All students will use critical-thinking, decision-

making, and problem-solving skills.

•

All students will demonstrate self-manage-

ment skills.

•

All students will develop career planning and

workplace readiness skills.

Health and Physical Education Standards

•

All students will learn health-promotion and

disease-prevention concepts and health-enhanc-

ing behaviors.

•

All students will learn health-enhancing, per-

sonal, interpersonal, and life skills.

•

All students will learn the physical, mental,

emotional, and social effects of the use and

abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs.

These standards show the central place of so-

cial and emotional skills in the context of work-

place skills that go across all areas of traditional

academic content, and as the centerpiece of

comprehensive health education. This is a pre-

cursor of future nationwide educational trends.

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

8

that everyone understood the importance of re-

specting one another and resolving problems coop-

eratively. We would venture to say that the vast

majority of readers share with the authors the expe-

rience of having such a teacher or being in such a

school, and that these experiences—and the feel-

ings associated with them—are part of why we are

dedicated to children and to schooling.

Given the growing lack of civility and the re-

lated problems educators see around them, it is not

surprising that they increasingly acknowledge the

importance of addressing social and emotional is-

sues in school. At the same time, some educators

believe they are “doing that already.” Perhaps this

is true. But just as we know instinctively that it

makes sense to identify the most effective practices

to teach a subject such as mathematics, take those

practices and structure them into a sequenced cur-

riculum, and implement that curriculum with

trained professionals during dedicated classroom

time, we must recognize now that the same effort

must be mustered if we are to succeed in the social

and emotional domains. It simply makes sense that

if we are to expect children to be knowledgeable,

responsible, and caring—and to be so despite sig-

nificant obstacles—we must teach social and emo-

tional skills, attitudes, and values with the same

structure and attention that we devote to tradi-

tional subjects. And we must do so in a coordi-

nated, integrated manner.

Parallel arguments in academic areas abound.

For example, all would agree that quantitative

skills, like skills for SEL, develop naturally. But few

would argue that just because quantitative reason-

ing skills develop without formal instruction, there

consequently is no need to offer systematic instruc-

tion in mathematics. Nonetheless, that is precisely

the refrain heard frequently about social and emo-

tional competence: it should be handled intuitively,

it should be gleaned from other subjects, it should

emerge on its own.

In today’s world, and in what we can foresee

as we enter the 21st century, nothing could be fur-

ther from the truth. Reflect for a moment on how

the world has changed in just the past five dec-

ades. Today, most children grow up in urban and

suburban settings in a high-tech, multimedia

world that provides constant stimulation, and

sends largely unregulated messages about material

goods and experiences that few youngsters experi-

ence directly or within their families. Many share a

classroom with students of diverse cultures and

perspectives and various abilities and disabilities.

In this world, millions of good and decent chil-

dren find that school is but one institution among

many influences in their lives. It competes with

peer groups, social service institutions, the media,

the culture of competition, the pressure to con-

form, the need to be different, the tug of religious

ties, the lure of risk, the fear of loneliness, and the

complexities of family relationships in an age on

the move. Youth who grow up in this world are all

of our children. They come from every ethnic, eco-

nomic, social, and geographic corner. Their teach-

ers are accustomed to watching them struggle with

the pressures and challenges of growing up. Learn-

ing at school is but a fragment of these challenges.

For this learning to take place effectively, so that

classroom lessons become life lessons, students

need significant adults and peers in their lives to

work with them as part of a community of learn-

ers. Only in such supportive contexts can they be-

gin to piece together answers to the sometimes

overwhelming social and emotional dilemmas they

face.

In a time when our youth need more support

than ever to master the tasks of development, we

see ironically that the economic and social changes

of the last 40 years of the 20th century have re-

duced those supports (Postman 1996). Many fami-

lies can make ends meet only when both parents

work outside the home—and sometimes at more

than one job. Extended families, which once pro-

vided a child-care safety net, have all but disap-

peared. And close-knit communities, once sources

of caring adults who guided children and served

The Need for Social and Emotional Learning

9

as role models, are today neighborhoods of

strangers.

Schools have become the one best place where

the concept of surrounding children with meaning-

ful adults and clear behavioral standards can move

from faint hope to a distinct possibility—and per-

haps even a necessity.

In our hearts, we know that the outcomes for

too many children are negative. Those who drop

out, those who go to out-of-district placements,

those who get through school thanks to waivers or

reduced standards, those who are in alternative

schools—all these students are not quite fully vis-

ible to us. We often do not know what becomes of

those who leave our particular class or school or

community. But others know. In every ethnic

group, in every geographic region, in every eco-

nomic bracket, children are letting us know that

the vise grip of growing up in a world that dimin-

ishes the importance of their social and emotional

lives is just too tight.

We will not repeat here the litany of statistics

of social breakdown in the lives of children. Read

your newspapers and magazines. Look at the

stream of books and articles put out by child advo-

cacy agencies. We should no longer need numbers

to make us bemoan current conditions. (For statis-

tics about changes in families and communities,

see Weissberg and Greenberg 1997, U.S. Depart-

ment of Health and Human Services 1996.)

The facts spell out a serious message:

We

should do more to prepare youngsters for the challenges

of life in our complex and fast-paced world

. In particu-

lar, these facts must be a wake-up call for educa-

tors in every classroom, at every grade level, and

in every school district in the United States:

These

are our children, and we must teach them in ways that

will give them a realistic chance of successfully manag-

ing the challenges of learning, growing, and developing

.

How Does This Book Contribute to

Efforts to Help Children Learn and

Grow?

This book suggests a practical, well-developed, de-

fensible strategy to help educators answer the

wake-up call. The strategy is to create programs for

comprehensive and coordinated social and emo-

tional learning from preschool through grade 12.

Such efforts will be benchmarked by at least three

main goals:

1. The presence of effective, developmentally

appropriate, formal and informal instruction in so-

cial and emotional skills at every level of school-

ing, provided by well-trained teachers and other

pupil-services personnel.

2. The presence of a supportive and safe school

climate that nurtures the social and emotional de-

velopment of children while including all the key

adults who have a stake in the development of

each child.

3. The presence of actively engaged educators,

parents, and community leaders who create activi-

ties and opportunities before, during, and after the

regular school day that teach and reinforce the atti-

tudes, values, and behaviors of positive family and

school life and, ultimately, of responsible, produc-

tive citizenship.

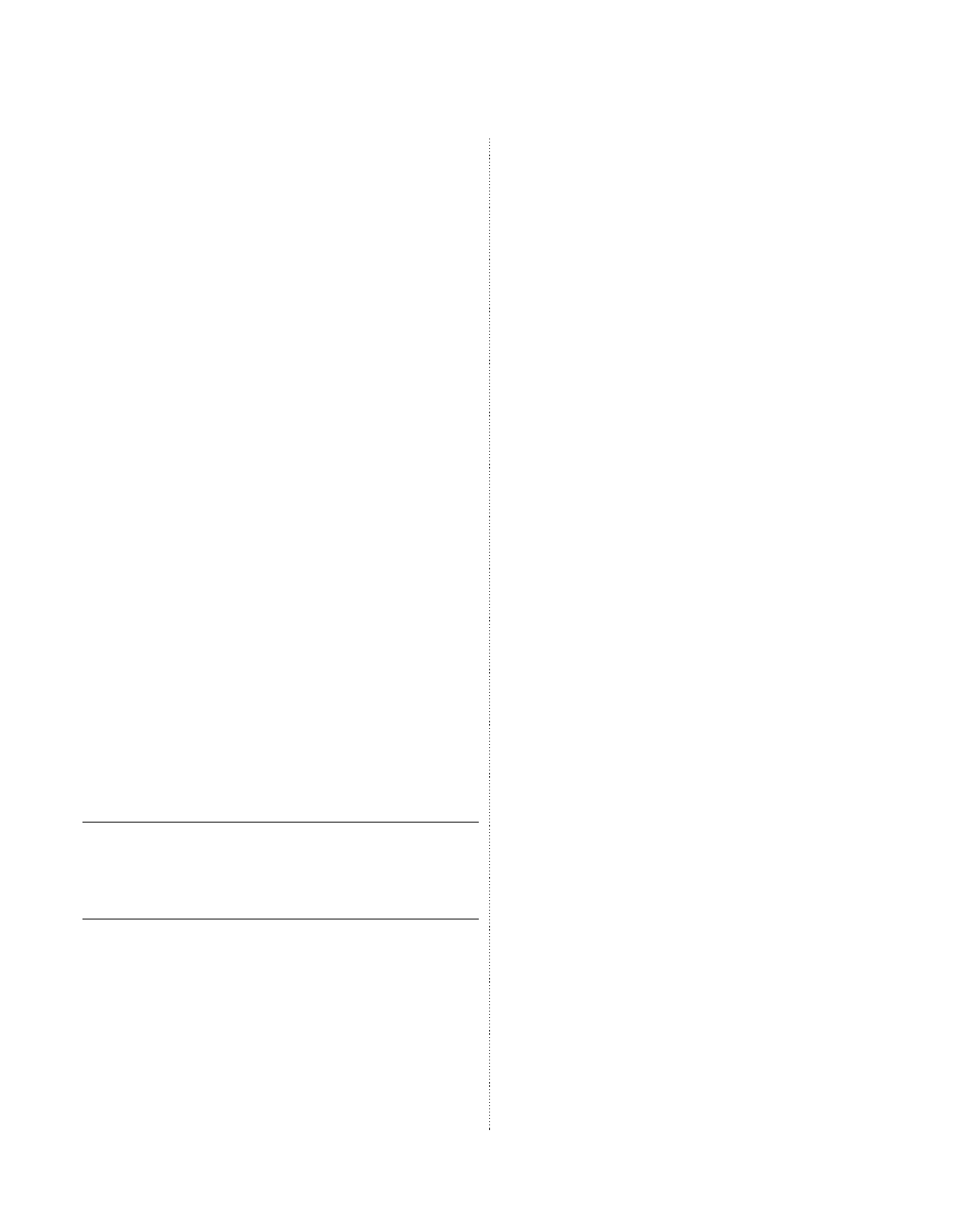

These three benchmarks should be assessed

along with outcomes in other domains to ensure

that schools are playing their part in giving young

people the best possible chance to become knowl-

edgeable, responsible, and caring adults. Specific

guidelines for reaching these goals and monitoring

these benchmarks are identified in the subsequent

chapters of this book. They describe social and

emotional education efforts that are integrated,

comprehensive, and coordinated—qualities lack-

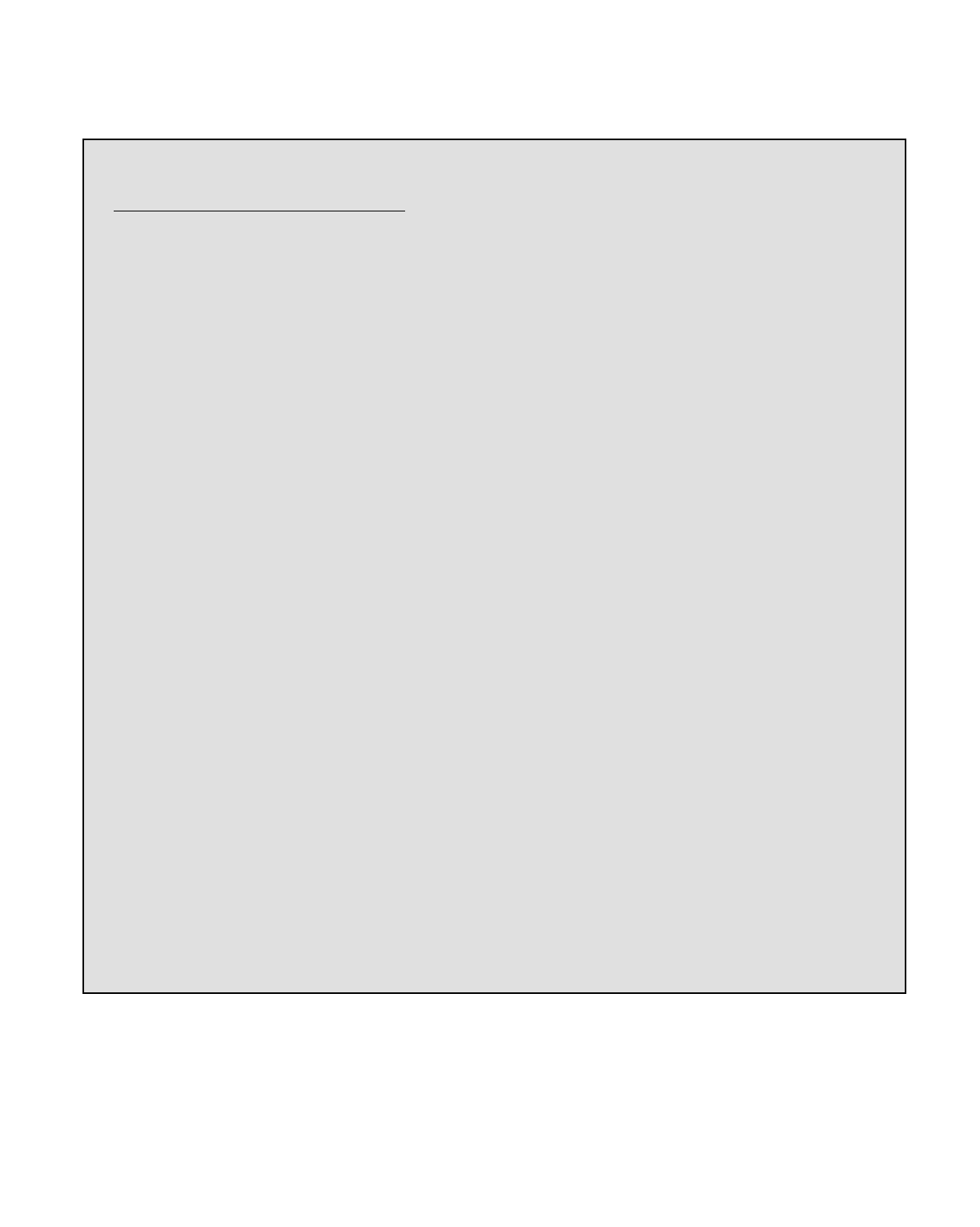

ing in many of today’s programs (see Figure 1.5).

They lead to students who are ready and moti-

vated to learn, increased academic performance, ac-

tive learning in the classroom and on the

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

10

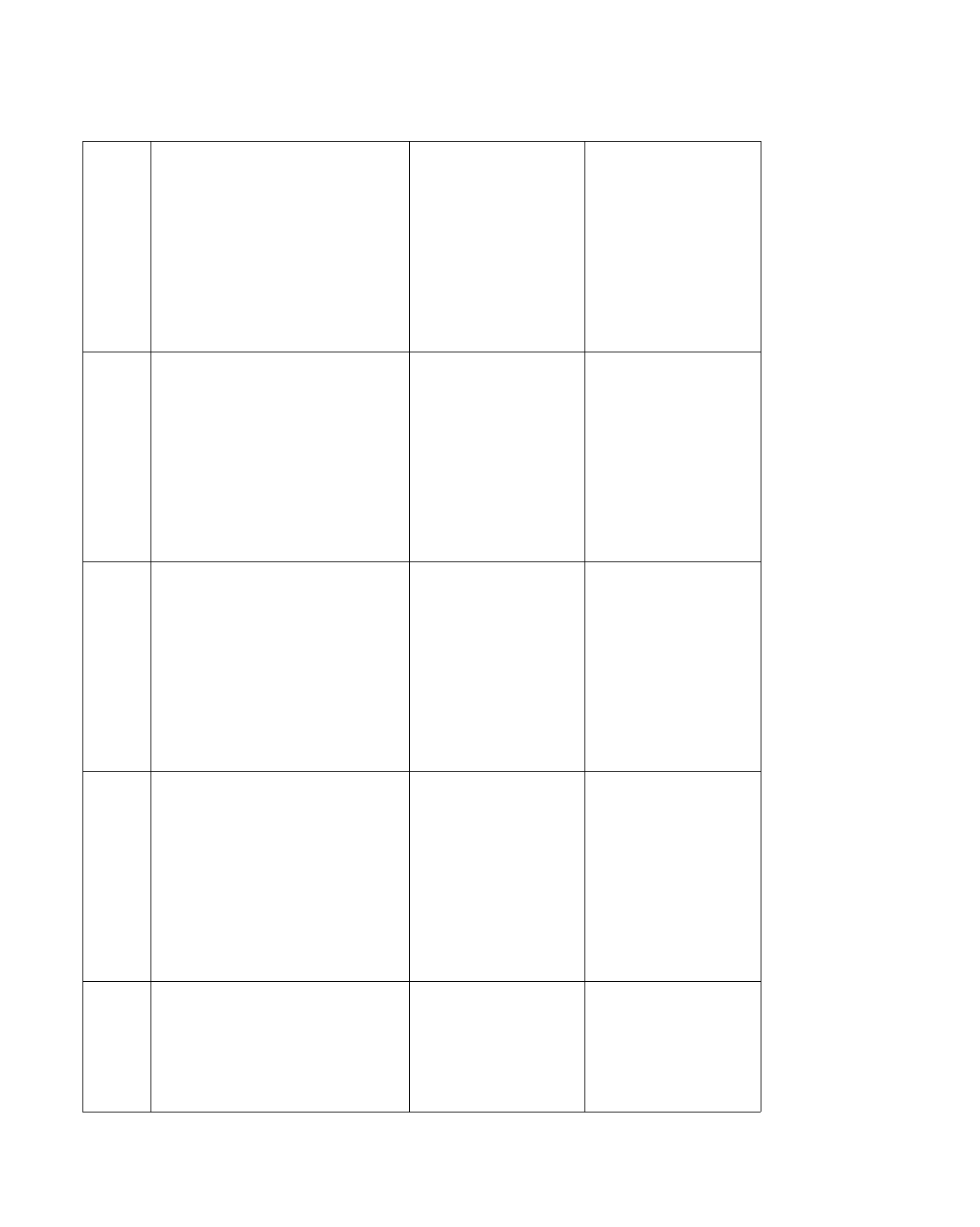

SUICIDE

PREVENTION

SUICIDE

PREVENTION

FUTURE

PREVENTION

PROGRAMS

FUTURE

PREVENTION

PROGRAMS

AIDS

EDUCATION

AIDS

EDUCATION

SCHOOL-BASED

DELINQUENCY AND

STRESS PREVENTION

SCHOOL-BASED

DELINQUENCY AND

STRESS PREVENTION

TEEN

PREGNANCY

PREVENTION

TEEN

PREGNANCY

PREVENTION

CHEMICAL

DEPENDENCY

PREVENTION

CHEMICAL

DEPENDENCY

PREVENTION

PREVENTION PROGRAMS WITHOUT

A COMMON FRAMEWORK

A COMMON FRAMEWORK

PROVIDES SYNERGY

SEL

F

IGURE

1.5

A

N

I

NTEGRATED

AND

C

OORDINATED

F

RAMEWORK

P

ROVIDES

S

YNERGY

Source:

Maurice J. Elias

The Need for Social and Emotional Learning

11

playground, greater respect for diversity, better

preparation for today’s society, and more effective

teachers and administrators.

Why are guidelines needed? Why, in the

crowded schedule of our school day, must we at-

tend systematically to this task as well? We cannot

afford to make social and emotional education a

fad; the work of Howard Gardner (1983), Daniel

Goleman (1995), James Comer (Comer, Haynes,

Joyner, and Ben-Avie 1996), and Carol Gilligan

(1987), among others, tells us why. The skills areas

these writers have identified are the fundamentals

of human learning, work, creativity, and accom-

plishment. Social and emotional development and

the recognition of the relational nature of learning

and change constitute an essential missing piece in

our educational system. Until it is given its proper

place, we cannot expect to see progress in combat-

ing violence, substance abuse, disaffection, intoler-

ance, or the high dropout rate.

This book is rooted in the idea that academic

and social success are not limited to those of good

fortune or privileged upbringing; we can create the

conditions for achievement for all children. Success

does not occur only through large programs; the

necessary conditions are created in families, in indi-

vidual classrooms, and through relationships with

special people in our lives. Here, we provide guide-

lines to foster these conditions in schools, program-

matically and systematically, so that their existence

for all children is left less to chance than is now the

case.

This, then, is a book about how to promote so-

cial and emotional learning in schools—how to

promote knowledgeable, responsible, and caring

children and adults. In our day, the real challenge

of educating is no longer

whether or not

to attend to

the social and emotional life of the learner. The real

challenge is

how

to attend to social and emotional

issues in education. This book suggests a course of

action for the “how” questions. It is a clarion call, a

shofar blast, a wail from a minaret, a church bell

ringing. We ask educators to rethink the ways in

which schools have addressed or failed to address

the development of the whole child, and to do so

with an eye toward models that have demon-

strated success. We ask readers to examine what

goes on in their classrooms, schools, and districts,

to determine how they can respond best to the op-

portunities described in this book.

More than anything, this is a book about com-

mon sense in education, or perhaps the uncommon

sense needed to recognize the missing piece in

schooling: enhancing the social and emotional life

of each student is part of the educational responsi-

bility of adults. We must remember that

the democratic way of life engages the crea-

tive process of seeking ways to extend and

expand the values of democracy. This proc-

ess, however, is not simply an anticipatory

conversation about just anything. Rather, it

is directed toward intelligent and reflective

consideration of problems, events, and is-

sues that arise in the course of our collective

lives (Beane and Apple 1995, p. 16).

An Overview of What Follows

This book reviews the essential elements underly-

ing the effective development, implementation,

and evaluation of SEL programs in a straightfor-

ward, practical, and systematic manner. In the next

chapter we ask you to begin thinking about the so-

cial and emotional education efforts already under

way in your classroom, school, or district. Doing so

will help to make the remaining content more ap-

plicable and meaningful for your specific setting.

The following three chapters present funda-

mental information for social and emotional educa-

tion. Chapter 3 provides a more in-depth

examination of what social and emotional educa-

tion is, as well as a discussion of its place in our

schools. This chapter provides the background in-

formation needed for Chapter 4, which explains

how teachers can help students develop social and

emotional skills in their individual classrooms. In

PROMOTING SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING: GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATORS

12

Chapter 5, important contextual issues related to

creating an organizational climate supportive of

social and emotional educational programs are

examined.

Chapter 6 gets down to practical issues in-

volved in starting and continuing a program. Chap-

ter 7 outlines ways in which social and emotional

education efforts can be evaluated to determine

whether they are achieving their goals and to pro-

vide guidance regarding changes that may be nec-

essary to make them more effective.

Most of the material in Chapters 3 through 7 is

presented in a series of concise guidelines that de-

scribe the development, implementation, and

evaluation of social and emotional education pro-

grams. The guidelines have a strong scientific basis

and are based on many research investigations and

relevant theory. They represent the combined ex-

pertise of program developers, researchers, train-

ers, and practitioners in this field.

In Chapter 8, the self-reflection process is revis-

ited to provide a starting point for you to get your

social and emotional education program under

way.

This book also includes three appendixes. The

first has a social and emotional education curricu-

lum scope, and the second a list of the guidelines

presented throughout the book. These are followed

by Appendix C, which is a list of programs that em-

phasize comprehensive approaches to social and

emotional education. Under the leadership of

Maurice Elias, CASEL conducted on-site visits to

schools that have implemented each of the pro-

grams included at the beginning of Appendix C. In-

cidentally, we have included examples throughout

the book to give you snapshots of what occurs in

SEL programs. Most of the examples were pro-

vided in response to questions posed by the site

visitors or were developed through observation.

Staff at the other programs listed in Appendix C,

which were not visited, have indicated to CASEL

that they include a strong emphasis on social and

emotional education strategies. You can gain addi-

tional firsthand knowledge about social and emo-

tional education efforts by contacting or visiting

the programs listed.

The Need for Social and Emotional Learning

13

Reflecting on Your Current Practices

2

T

O BEGIN THE PROCESS OF IMPROVING THE

OPPOR-

tunities for social and emotional learning that you

already provide, we invite you to begin thinking

about your classroom, school, or district. We chal-

lenge you to think about what you

are

doing to pro-

mote SEL and what you

could be

doing. This

process will help you begin to think about SEL is-

sues, which will make the rest of the book more

relevant to your particular setting. Further,

whether you are a novice or an experienced hand

at providing SEL instruction, it is important to

regularly reflect on your professional actions and

to develop a thorough understanding of why you

have chosen them.

No matter what your professional position, be

it teacher, principal, or superintendent, we believe

you will find that you and your school or district

are already doing a lot—probably more than you

realize once you begin listing everything. Once

you are finished with this chapter, you will prob-

ably be thinking about how you might improve

what you are doing and what more could be done.

At some point, you may want to engage in this self-

reflection process with a team of colleagues repre-

senting different positions and perspectives. This

collaborative exploration will likely spark informa-

tive discussions and debates about what activities

constitute social and emotional education as well

as creative brainstorming about how to integrate

and coordinate classroom, school, and community

efforts to enhance students’ social and emotional

skills.

To get you started, here are some general ques-

tions to address. You don’t have to answer all of

them now. Some may be more relevant to you than

others, depending on your role in the school or dis-

trict. The questions are structured around the 39

guidelines presented in Chapters 3 through 7 (Ap-

pendix B lists all the guidelines). We encourage

you to initiate this self-reflection process by think-

ing about and discussing some of the issues raised

in this chapter. Doing so will foster a more focused

and critical approach to reading the next five chap-

ters. As you go through this process, we think you

will find it helpful to put your reflections and ideas

in writing so you can refer to them later.

After you and your colleagues review the first

seven chapters, we urge you to reconvene and en-

gage in the more thorough self-assessment offered

in Chapter 8. That chapter’s exercise will help you

identify strengths in current program efforts, iden-

tify priorities for new initiatives and directions,

and develop a plan for your next steps. The notes

we are urging you to keep will stimulate your

thinking about specific steps to take and encourage

you to think about all the practical aspects of begin-

ning your renewed SEL programming efforts.

15

What Is My School Doing to Foster

Social and Emotional Learning?

I. Identifying Your SEL Goals and Activities

See Chapter 3 and Appendix A for more informa-

tion about this area.

1. What are the SEL goals for your classroom,

school, or district that will help students be-

come knowledgeable, responsible, and caring?

2. Develop a written list of activities going on in

your classroom, school, or district that support

SEL. Think broadly when considering what to

include on the list. For example, include the fol-

lowing: programs to enhance life skills, prob-

lem solving and decision making, positive

youth development, self-esteem, respect for di-

versity, and health; efforts to prevent problems

such as substance abuse, AIDS, pregnancy, and

violence; conflict resolution and discipline ap-

proaches; support services to help students

cope with school transitions, family disrup-

tion, or death; and positive contributory serv-

ice, peer leadership and mediation,

volunteerism, mentoring, character education,

civics and citizenship, or career education.

•

What approaches are you taking to en-

hance the SEL of students in the classroom

(e.g., specific curriculums, variety of fo-

cused activities)?

•

On what theory are you basing these activi-

ties? In other words, why are you engag-

ing in them?

•

What activities outside the classroom, but

within the school context, support SEL

(e.g., extracurricular activities, clubs, play-

ground games)?

•

What community activities support the

school’s SEL efforts?

•

What home activities are taking place that

complement the school’s SEL program?

3. Are these SEL efforts planned, ongoing, sys-

tematic, and developmentally based?

4. Are efforts to prevent problems and promote

positive cognitions, emotions, and behaviors

coordinated with one another, or are they con-

ducted in a piecemeal fashion?