The University of Southern Mississippi The University of Southern Mississippi

The Aquila Digital Community The Aquila Digital Community

Honors Theses Honors College

5-2023

Language Experience: The Perception of Foreign Language Language Experience: The Perception of Foreign Language

Acquisition Among University Adults Acquisition Among University Adults

Lileth A. Stricklin

Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses

Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the First and Second

Language Acquisition Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Stricklin, Lileth A., "Language Experience: The Perception of Foreign Language Acquisition Among

University Adults" (2023).

Honors Theses

. 894.

https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/894

This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital

Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila

Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected].

Language Experience: The Perception of Foreign Language Acquisition Among

University Adults

by

Lileth A. Stricklin

A Thesis

Submitted to the Honors College of

The University of Southern Mississippi

in Partial Fulfillment

of Honors Requirements

May 2023

ii

iii

Approved by:

Carmen Carracelas-Juncal, Ph.D., Thesis Advisor,

School of Social Science and Global Studies

Edward Sayre, Ph.D., Director,

School of Social Science and Global Studies

Sabine Heinhorst, Ph.D., Dean

Honors College

iv

ABSTRACT

While bilingualism has always existed within the history of the U.S. and is the

global norm, mainstream approaches to learning have traditionally been monolingually

centered and fail to employ approaches that produce sustainable motivation towards

foreign language acquisition in students. This study sought to investigate the perceptions

adult individuals display towards acquiring foreign language skills, emphasizing

distinctions exhibited between monolinguals and their multilingual counterparts. A

mixed-method approach in the analysis of 506 survey responses yielded results that

suggest that university adults generally display positive perceptions towards foreign

language learning. Distinctions in perception between monolinguals and multilinguals

were very few with main ones centering on differences in the intensity of sentiments felt

for positive, neutral, and negative statements on foreign language; differences in lived

experiences from which anecdotal evidence is drawn; and expressions of regret and/or

unrealized desire. Findings also support the existing theory found in Masgoret & Gardner

(2003), that suggests that level of motivation remains the determinant factor of whether

one is likely to be persistent in the learning process to achieve success. This study intends

to contribute to the discussion of how to create better educational curricula and social

initiatives that encourage openness to acquiring and utilizing languages other than

English within the U.S.

Keywords: Foreign language acquisition, monolingual, multilingual, perception,

qualitative, mixed method

v

DEDICATION

This thesis is in dedication to those in my life who have invested in me and my education

and fostered my curiosity for Spanish.

It is due to your nourishing efforts that I have become the well-formed

scholar and person that I am today.

vi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the Honors College at The University of Southern

Mississippi for providing me with a holistic educational experience and supporting me in

all my undergraduate endeavors. For every challenge and dream that I had, I knew that I

could always turn to them for help. I also want to give special thanks to Dr. Sabine

Heinhorst for being a great and understanding professor of HON 300 & 301 when she

taught it, and for being a great Interim Dean of the Honors College.

Dr. Michelle McLeese must be recognized for her willingness to help me navigate

qualitative analysis software when I didn’t quite know what I was doing, and for lending

me her book to use while I powered through the laborious process. Her weekly Pilates

class at the Payne Center was a perfect outlet for releasing my frustrations when they

arose.

My greatest thanks goes to Dr. Carmen Carracelas-Juncal, who served as my

Spanish advisor, thesis advisor, and professor over the last three years. It has been under

her direction that I have been further exposed to the world of Spanish beyond what I

could have ever imagined. Not only has she been a knowledgeable and passionate

professor I could always turn to, but she was the one who pushed me to take advantage of

opportunities outside the classroom such as studying abroad in Spain, interning in

Washington, D.C., and applying to take a gap year abroad post-graduation. Even though

the thesis process was arduous at times, Dr. C’s guidance and reassurance provided me

with the confidence needed to complete my first grand project. To her, I express deep

gratitude.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. xi

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ............................................................................................ xii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... xiii

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ..................................................................... 3

Research on Orientation/Attitude and Motivation .......................................................... 5

Globalization and Shifting Trends—Their Significance and Implications................... 11

METHODOLOGY .................................................................................. 15

Research Questions ....................................................................................................... 16

Participants .................................................................................................................... 16

Research Design............................................................................................................ 17

Qualitative Design and Analysis ............................................................................... 17

Theoretical Issues...................................................................................................... 19

Data Collection Procedures........................................................................................... 22

Instrument ................................................................................................................. 23

Demographic Collection ....................................................................................... 23

Language Probe .................................................................................................... 23

Likert Scales.......................................................................................................... 24

Extended Response ............................................................................................... 25

viii

Data and Analysis ......................................................................................................... 26

Limitations of the study ................................................................................................ 29

RESULTS ................................................................................................ 32

Quantitative Analysis .................................................................................................... 32

Demographic Information ......................................................................................... 32

Likert Scales.............................................................................................................. 36

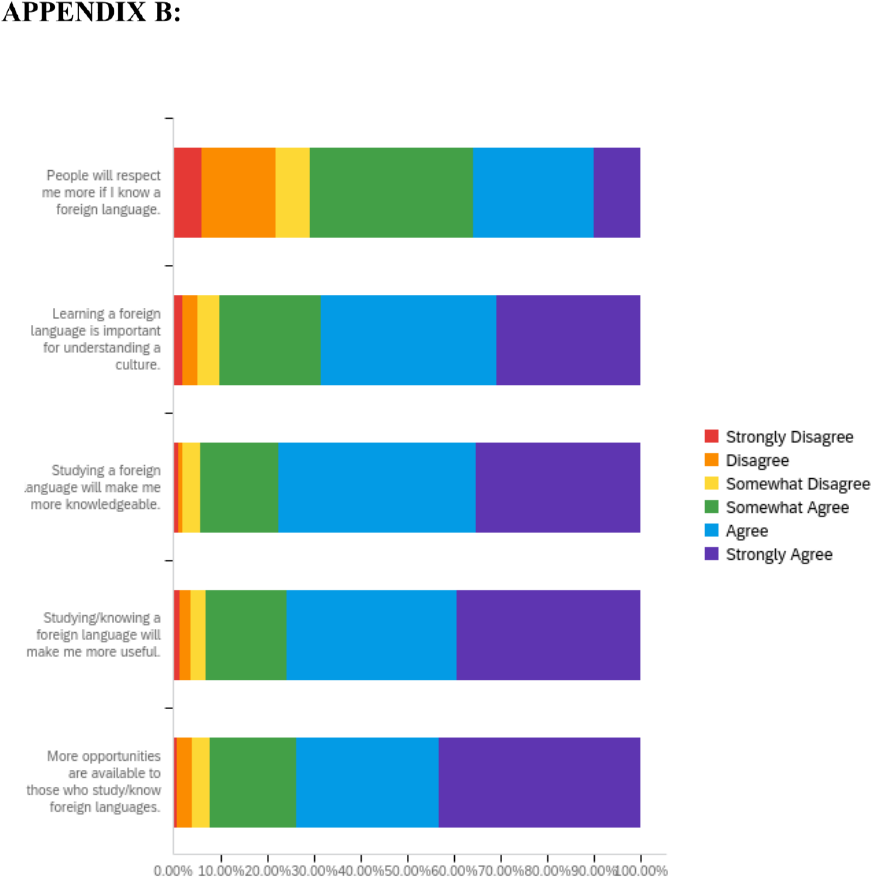

Positive Likert Statements .................................................................................... 37

Neutral Likert Statements ..................................................................................... 38

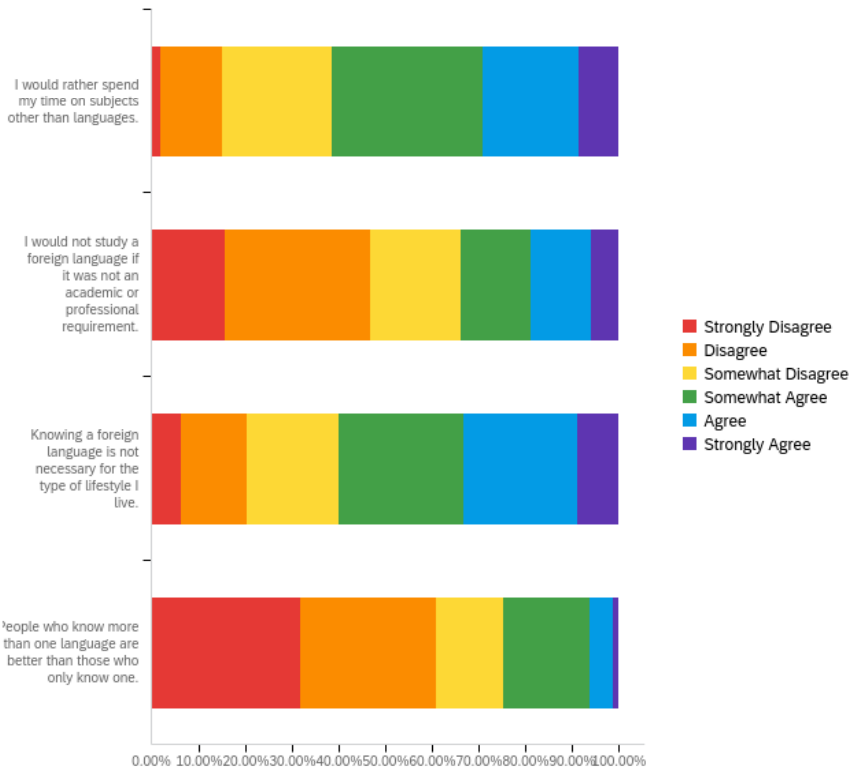

Negative Likert Statements ................................................................................... 40

Qualitative Analysis ...................................................................................................... 43

Prompt 1: People who know more than one language are better than those who only

know one. .................................................................................................................. 45

Theme 1: Attributes .............................................................................................. 46

Theme 2: Motivation............................................................................................. 46

Theme 3: Instrumentality ...................................................................................... 47

Prompt 2: Anyone could learn a foreign language if they wanted to. ...................... 49

Theme 1: External Conditions .............................................................................. 50

Theme 2: Internal Conditions ............................................................................... 52

Comparison ........................................................................................................... 53

Prompt 3: Studying/knowing a foreign language will make me more useful........... 54

ix

Theme 1: Instrumental Benefits (Context). .......................................................... 54

Theme 2: Instrumental Benefits (Manner) ............................................................ 54

Comparison ........................................................................................................... 56

Prompt 4: Every person should know more than one language................................ 56

Theme 1: Benefits (Recognition) .......................................................................... 56

Theme 2: Situated Context (Evaluation)............................................................... 57

Theme 3: Ultimate Decision (Conclusion) ........................................................... 58

Comparison ........................................................................................................... 59

Prompt 5: (Optional): Based on the type of prompts you have encountered today, are

there any other thoughts and/or opinions you would like to express regarding foreign

language? .................................................................................................................. 60

Comparison ........................................................................................................... 60

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS .................................................................. 64

CONCLUSION ....................................................................................... 72

SURVEY ................................................................................................. 76

LIKERT SCALE RESULT VISUALIZATIONS ................................... 80

CODE LISTS .......................................................................................... 86

Code List 1: S1MoreLanguageBetterThan ................................................................... 86

Code List 2: S2AnyoneLearnLanguage ........................................................................ 86

Code List 3: S3LanguageMakesMeUseful ................................................................... 87

x

Code List 4: S4EveryoneShouldKnowLanguage ......................................................... 87

Code List 5: Q5FreeReponseOptional .......................................................................... 88

IRB Approval letter ................................................................................. 89

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 90

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1. Demographic Information of Respondents ...................................................... 32

Table 1.2. Language Background of Respondents ........................................................... 34

Table 1.3. Language Background of Respondents’ Parents ............................................. 36

Table 2.1. Positive Likert Statements ............................................................................... 38

Table 2.2. Neutral Likert Statements ................................................................................ 40

Table 2.3. Negative Likert Statement ............................................................................... 42

Table 3.1. Prompt to Code List ......................................................................................... 44

xii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1. Thematic Model................................................................................................. 64

Figure 2.1. Positive Likert Items—Monolingual .............................................................. 80

Figure 2.2. Positive Likert Items—Multilinguals ............................................................. 81

Figure 2.3. Neutral Likert Items—Monolingual ............................................................... 82

Figure 2.4. Neutral Likert Items—Multilinguals .............................................................. 83

Figure 2.5. Negative Likert Items—Monolinguals ........................................................... 84

Figure 2.6. Negative Likert Items—Multilinguals ........................................................... 85

xiii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ELL English Language Learners

ESL English as a Second Language

ICC Intercultural Communication

L2 Second Language

1

INTRODUCTION

This project investigates the perceptions adult university students display towards

acquiring foreign language skills with an emphasis on distinctions exhibited between

monolinguals and their bilingual/multilingual counterparts. For a long time now, it has

been in the interest of institutions to promote language learning in some form, whether it

be teaching students, helping non-native speakers assimilate to their country of residence,

conducting diplomatic transactions, community organizing, etc. While bilingualism has

always existed within the history of the United States and is the global norm, mainstream

approaches to learning have traditionally been monolingually centered, emphasizing and

considering factors of monolingual learners rather than those who already exhibit

characteristics of multilingual ability. It is very probable that multilingual individuals

present different perceptions on the importance of language learning from their

monolingual counterparts, or if not, reasoning behind their purported perceptions do.

There has not been adequate qualitative investigation of factors that influence how we

regard something as important as language learning, and while more work is required to

collect and study material that is inherently subjective, there is much value in information

that may be more psychological and personal in nature.

It is the intention of this investigation to better understand existing incentives,

deterrents, and general perceptions regarding learning a foreign language as reported by

participants. Findings may help contribute to the creation of better educational curricula

or promotional campaigns that encourage openness to acquiring and utilizing another

language other than English. It is likely that inquiries from this study into people’s

reported postures may reveal a plethora of other considerable factors contributing

2

towards the general adult perception of language. To address concerns that this

investigation is too duplicative in nature to other previously conducted self-report survey

studies, it is important to consider that demographics in the United States are

continuously in flux, and measurement of public opinion and perception must be updated

to effectively create models that align and address these realities. Therefore, this research

aims to help provide more updated analyses of attitudes towards language acquisition

among adults that emphasize qualitative aspects adding to existing literature within the

field.

While multilingual is typically used to refer to those who speak more than two

languages, the researcher for this study has chosen to incorporate those who speak two

languages (bilinguals) or more under the label multilingual and will be used as such

throughout this study. The next chapter will provide a review of literature that highlights

key ideas found in previous studies pertaining to language learning and the impact

globalization has had on the demand, or lack thereof, for linguistic diversity. Following

the review of literature, the next chapters will discuss the methodology, results,

discussion of results, and conclusion of the study.

3

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Independent from its setting, language acquisition often seems to be a matter of

motivation and is determined by perceived necessity and/or desire to learn such language

by each individual. Qualitative inquiry is best suited to reveal descriptive insight into the

motives that either drive or dissuade one from partaking in this endeavor. This chapter

will examine key findings from previous research on attitudes and motivation pertaining

to language learning. Additionally, trends of globalization and its impact on foreign

language demands will also be discussed.

Previous studies on second language have largely focused on established

correlational trends among school-age test populations and are often conducted within

pedagogical contexts (Masgoret & Gardner, 2003; Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005; Merisuo-

Storm, 2007; Acheson, Nelson, & Luna, 2015; Russel & Kuriscak, 2015; Byers-Heinlein,

Behrend, Said, Giris, & Poulin-Doubois, 2017). Distinct groups are often emphasized in

research to produce further insight into characteristics displayed by such groups and to

provide material for comparison: native versus heritage speakers, monolinguals versus

bilinguals, anglophones versus others, control group versus experimental, etc. (Acheson

et al., 2015; Byers-Heinlein et al., 2017; Merisuo-Storm, 2007; Russel & Kuriscak,

2015). Among such studies, a quantitative research approach is the typical method

employed with variables being operationalized in such a manner that allows for statistical

analysis and interpretation by researchers. Quantitative inquiry has come to have an

important place within the social sciences and is difficult for many to completely

abandon with ease; however, overreliance on its methods and interpretive approach can

4

pose problems for inquiry into issues centered around elements of perception, values,

beliefs, and attitudes that largely require a qualitative approach.

While quantitative evidence may serve to enhance credibility of declared

hypotheses and interpretation of outcomes, lack of qualitative procedures leaves a gap in

material used for evaluative interpretation by researchers. As Saldaña (2003) notes,

classic quantitative instruments used to measure “values, attitudes, and beliefs about

selected subjects” tend to use scales that “assume direction and intensity […]

necessitating a fixed linear continuum of response (e.g., less to more, strongly agree to

strongly disagree) rather than a three-dimensional ocean allowing for diverse responses

and varying levels of depth” (pp. 91–92 as cited in 2016, p. 135). Saldaña (2016)

summarizes the role of qualitative inquiry as “provid[ing] richer opportunities for

gathering and assessing, in language-based meanings, what the participant values,

believes, thinks, and feels about social life” (p. 135). Acheson et al. (2015) note that

further qualitative measures would need to be implemented in future research “to provide

language educators with a deeper understanding of such things as learners’ motivation to

study another language, their personal values and orientations, or the extent of their

interactions with speakers of other languages” (p. 212). Researchers’ inferences are

inadequate in providing insight into the causes and rationale behind participants’

behaviors without some form of qualitative data. Such inference of interpretation between

data and conclusions provide opportunities for the creation of studies in which

participants may offer elaboration of their own explicit beliefs, opinions, and attitudes

that helps supplement existing quantitative research as will be discussed next.

5

Research on Orientation/Attitude and Motivation

Studies on language learning traditionally center on measuring some aspect of

motivation, attitude, or orientation using foundations derived from R. C. Gardner’s

socioeducational model comprised of five interrelated variables: integrativeness, attitudes

toward the learning situation, motivation, integrative orientation, and instrumental

orientation (Masgoret & Gardner, 2003). As research in the field has progressed, the

conceptualization and names of these variables have evolved to include several

interpretations of how such criteria may be observed among diverse test populations in

differing contexts. Nevertheless, Gardner’s framework on motivation/attitude has

remained the foundational basis for research on language learning and motivation

(Ushioda, 2017, pp. 474–475; Masgoret & Gardner, 2003). Among all variables of

Gardner’s socioeducational model, motivation and its factors of integrativeness,

instrumentality, and their respective orientations have been proposed to be the most

influential in determining success in second language learning, as will be discussed

below (Masgoret & Gardner, 2003).

Instrumentality is a characterization of motivation concerned with “the pragmatic

incentives” that exist around language learning and acquisition (Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005,

p. 21). According to Cook (2001), “instrumental motivation means learning the language

for an ulterior motive unrelated to its use by native speakers—to pass an examination, to

get a certain kind of job, and so on” (p. 115). Traditionally, instrumentality has been

defined by its utilitarian aspect that is typically generated by extrinsic motives.

Integrativeness, on the other hand, has traditionally been defined as “an openness to

identify, at least in part, with another language community” (Masgoret & Gardner, 2003,

6

p. 172) that generally reflects a positive association with the target language and a desire

to engage in its culture (Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005, p. 20; Cook, 2001, p. 114). Both

instrumentality and integrativeness can easily and mistakenly be regarded as distinct and

mutually exclusive concepts; however, as will be discussed later in this section, the two

overlap considerably when forming motivation.

Two main issues that have arisen from traditional notions of

instrumental/integrative classification among researchers are the conflation between

motivation and orientation, and the inability to clearly distinguish when participant data

is either instrumental or integrative due to limited theoretical scope. According to

Masgoret and Gardner (2003), motivation is a “goal-directed behavior (cf. Heckhausen,

1991)” (p. 173) that presents several features within an individual:

The motivated individual expends effort, is persistent and attentive to the task at

hand, has goals, desires, and aspirations, enjoys the activity, experiences

reinforcement from success and disappointment from failure, makes attributions

concerning success and/or failure, is aroused, and makes use of strategies to aid in

achieving goals. That is, the motivated individual exhibits many behaviors,

feelings, cognitions, etc., that the individual who is unmotivated does not. (p.173)

Orientation, on the other hand, has a closer likeness to attitude which is more likely to

reflect one’s mental disposition or posture towards a particular concept. As Gardner

makes clear throughout his research, orientation and motivation do tend to display a

positive correlation with one another; however, motivation is not necessarily always a

reflection of orientation and therefore cannot be considered equal (Masgoret & Gardner,

7

2003, pp. 175–177). Masgoret and Gardner (2003) provide the following example to

illustrate this distinction:

Noels and Clément (1989), for example, demonstrated that some orientations are

associated with motivation and some are not. That is, one might profess an

integrative orientation in language study but still may or may not be motivated to

learn the language. Similarly, one might profess an instrumental orientation, and

either be motivated or not to learn the language. (p. 175)

Success in language learning seems to be primarily determined by motivation more than

any other factor in the socio-educational model. Therefore, it does not necessarily matter

whether one displays either an integrative or instrumental orientation/attitude, so much as

whether they possess a strong enough motivation capable of driving an individual to

achieve their goal regardless of how the motivation is characterized (Masgoret &

Gardner, 2003, p. 175). With that being said, the socio-educational model does propose

that motivation itself can be influenced by other variables such as integrativeness,

instrumentality, and orientation, and therefore can have an indirect effect on outcomes

generated from motivation (Masgoret & Gardner, 2003, p. 205). Of all tested variables,

integrative motivation has displayed the highest correlation with outcomes of success and

is generally thought to be the most important factor in contributing to achievement in

second language acquisition (Masgoret & Gardner, 2003, p. 201). Gardner’s model is

foundational in the study of language learning as it pertains to attitude and motivation;

however, certain difficulties arise when considering how to apply such theoretical

concepts in a practical fashion.

8

Csizér and Dörnyei (2005) remark on how the popularized concept of

integrativeness has led to its incorporation into “several theoretical constructs of L2

motivation” despite its exact nature remaining obscure (pp. 20–21). Simply put, nuance

and complexities found within people’s reasonings behind language learning make it

difficult to easily identify and classify what qualifies as being integrative or not; this

same issue can be extended to instrumentality. To illustrate this difficulty, Dörnyei (1994,

2002) points out how things traditionally considered as utilitarian benefits (e.g., obtaining

employment; entrance admissions, etc.) might not be as relevant to certain participant

groups as other things not normally considered under this label such as traveling, making

friendships, understanding foreign media for pleasure, etc. Moreover, the characterization

of instrumentality and integrativeness as “antagonistic counterparts” has never been

endorsed by Gardner, but rather have always been acknowledged as being

complementary, with Csizér and Dörnyei (2005) going as far as to propose that

instrumentality can in fact feed into integrativeness as a “primary contributor” (p. 27).

Such extensive amounts of overlap between instrumentality, integrativeness and the

ambiguity contained within each warrants an expansion of what is understood to classify

under the instrumental category while also reconceptualizing the idea of integrativeness

itself.

To reconceptualize existing ideas within literature, it is often helpful to look to

other fields of study for inspiration. Building off the “possible selves” framework of

Markus and Nurius (1986), Csizér and Dörnyei propose Higgin’s (1987, 1996) concepts

of the “ideal self” and “ought self” as a better alternative to integrativeness (Csizér &

Dörnyei, 2005, p. 29). The ideal self is a representation of “attributes a person would like

9

to possess” and contains a “promotion focus, concerned with hopes, aspirations,

advancement, growth, and accomplishments”, while the “ought self” represents

“attributes people believe they ought to possess” and has a “prevention focus, regulating

the absence or presence of negative outcomes, concerned with safety, responsibilities,

and obligations” (Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005, p. 29). Moreover, they propose that

instrumentality can be divided into two distinct classes “depending on the extent of

internalization of the extrinsic motive” that make up the concept (2005, p. 29). Less

internalization will produce increased association with the ought self, while increased

internalization produces increased association with the ideal self/Ideal L2 Self (Markus &

Nurius, 1986 as cited in Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005, pp. 22; 29–30). Csizér and Dörnyei

(2005) ultimately propose that the “Ideal L2 Self” replace the traditional label of

integrativeness as it is more expansive in the interpretation of the concept and better

accommodates aspects of motivation and attitude together (p. 30). Regardless of how one

chooses to characterize the concepts, integrativeness and instrumentality are the two most

common descriptions of orientation and motivation used in the study of language learning

and will likely continue to be so. In addition to the characterization of motives and

motivation, exposure also plays a notable role in influencing attitudes formed in language

learners as will be discussed below.

Levels and types of exposure to foreign languages and their respective cultural

groups have great potential to shape attitudes towards learning. Because

attitude/orientation is positively correlated with motivation, negative attitudes are likely

to reduce learner motivation whereas the opposite is true for positive attitudes (Merisuo-

Storm, 2007, p. 228). Some researchers of bilingual education suggest that foreign

10

language as a medium of communication through which one receives new information

increases the likelihood of a learner developing more positive attitudes towards the

language overall (Richards & Rodgers, 2001, p. 207; Curtain & Martinez, 1990 as cited

in Merisuo-Storm, 2006, p. 227). Not only is it imperative that students be exposed to

foreign language in some substantial form, but it must be ensured that such exposure

must itself be positive and highlight the importance of cross-cultural exchange and

communication (Kubota, 2016). Acheson et al. (2015) suggest intercultural

communication (ICC) instruction as an instructional approach used to foster positive

attitudes toward languages and cultures by serving as a supplement to standard language

curriculum that addresses “the practices, products, and perspectives of culture that

emphasize[s] the development of intercultural competence” (pp. 204–206). Similar

sentiments are expressed by Kubota (2016) who proposes that “dispositional

competence” must be addressed by language professionals to cultivate individuals who

display increased willingness to communicate, accommodate, learn, and respect other

languages, cultures, and people (p. 477). In sum, to create positive attitudes towards

foreign languages and L2 cultures, increased positive exposure that facilitates cultural

exchange and mutual respect is necessary to cultivate competent communicators.

To summarize, attitude and motivation are integrally tied together as each one

influences the other and are shaped by similar factors. Instrumentality is largely

concerned with utilitarian incentives for language learning, while integrative incentives

can be characterized by a view of promotion that involves unifying an aspect of oneself

with that of a target language and/or its culture. Neither is mutually exclusive and both

factors can shape the nature of one’s motivational posture. Additionally, levels and types

11

of exposure have been shown to correlate with the type of attitude one holds towards a

target language and its speakers. Current trends of socio-cultural and economic

globalization have caused researchers to consider how increasingly extrinsic forces will

influence motivation of language learners, particularly monolinguals. In terms of the

demand for certain languages and its necessity for certain demographics, researchers

offer a variety of predictions for what they believe will be the future of language learning

further discussed in the next section.

Globalization and Shifting Trends—Their Significance and Implications

Interaction with foreign language and its related byproducts has increased in

recent times due to globalization and widespread commercialization. The process of

globalization has increased in its “intensity, scope, and scale” with its sheer magnitude

and depth threatening the traditional notion of “one nation—one language” ideology

along with its “nationing” mechanism (Fishman 1972, as cited in Lo Bianco, 2014, p.

313). Expanded forms and characteristics of human movement in recent decades have

resulted in plurilingual societies, particularly for countries that serve as immigration

destinations such as the U.S. (Budiman, 2020, para. 1 & 11). As Kubota (2016) points

out, competency in English is extremely useful “for socio-economic mobility” in today’s

globalized society where proficiency in another language helps “to develop a competitive

edge” over others in seeking global career opportunities (pp. 467–468). English has been

predicted to “become commonplace in the world’s labor markets” as proficiency in the

language continues to grow globally (Ushioda, 2017, p. 470). Monolinguals and even

bilinguals are expected to lose out to their multilingual counterparts over time, thereby

12

losing their competitive advantage in the global marketplace (Ushioda, 2017, p. 470). As

eloquently stated by Graddol (2007) in his English Next review for the British Council,

The competitive advantage which English has historically provided its acquirers

(personally, organizationally, and nationally) will ebb away as English becomes a

near-universal basic skill. The need to maintain the advantage by moving beyond

English will be felt more acutely. (Lo Bianco, 2014, p. 322)

One would think that if multilinguals are to develop a greater competitive advantage in

the global market, there would be more incentive for individuals (particularly

monolingual anglophones) to further develop language skills under an instrumental

motivation/utility basis; however, current research has shown mixed results regarding this

assumption. Some research suggests that the spread of global English negatively affects

motivation to learn other languages for anglophones despite increasingly pluralist and

diverse societies continuing to grow (Dörnyei, Csizér, & Németh, 2006; Taylor &

Marsden, 2014 as cited in Ushioda, 2017, p. 470). With conflicting predictions and

research on global trends and language demands present, one must more closely analyze

other factors outside the linguistic scope to perhaps acquire a better understanding of

existing incentives and deterrents.

Why is it then that in an increasingly globalized society, the proliferation and

dominance of English persists? Lo Bianco (2014) proposes economic globalization as a

principal factor determining the selection of languages taught in education systems and

beyond (pp. 316–317). To reflect this trend, there has traditionally been a high demand

for English in non-English-speaking countries, and a low demand for foreign language in

English-speaking ones (Lo Bianco, 2014, p. 317). This emphasis on developing English

13

as a skill demonstrates the common practice of human capital investment and is a

development process that stems from utilitarian motivation (Kubota, 2016, p. 469 as cited

in Ushioda, 2017, p. 472). Lo Bianco (2014) argues that such hyper-demand for English

often removes utilitarian reasoning for foreign languages in countries that speak English

(p. 317). However, he also notes an exception to this low-utilitarian demand for foreign

language in the U.S. caused by “continually replenished Spanish-speaking migration”

that produces a need for Spanish proficiency (p. 317). As more multilinguals learn and

utilize the established dominant language of a cultural setting, it is very reasonable to

suggest that monolinguals will eventually lose out to their counterparts who hold greater

competitive advantage.

Ushioda (2017) argues that an instrumentalist approach driving language learning

policies is detrimental to deeper, long-term promotion of languages since it essentially

pits economic interests against more holistic approaches to learning, stating that:

current ideologies and discourses shaping language education policy and

curriculum […] is often explicitly linked to factors such as economic and utility

value, employability, social prestige, necessity, or global and national security.

While such factors may help explain growth in uptake of certain languages

accorded important global or critical status […] this instrumentalist view would

seem to communicate a rather narrow rationale for learning languages that may

not resonate with the motivations and priorities of everyone. (pp. 471, 479)

Ushioda (2017) suggests the promotion of an approach embodying “ideal multilingual

selves” serves as a better alternative to help individuals who may be uninterested and

disengaged from linguistic plurality and overall language learning (pp. 478–479). This

14

suggestion would seem to be in line with Csizér and Dörnyei’s (2005) suggestion of the

“Ideal L2 Self” being the most important factor shaping motivated behavior in language

learning rather than the standard instrumentalist approach (pp. 22 & 29). The decision of

how to frame and teach languages in educational curricula is primarily dependent on

whether an institution or person views the task as an instrumentalist or integrative

endeavor.

To conclude, personal postures or perceptions people hold towards a particular

phenomenon are greatly influenced by factors of motivation and attitude. While there is

much interplay between variables that determine motivation and attitude as discussed in

the prior section, it is known that characterization of such variables as being either

integrative, instrumental, or both are key in predicting long-term motivation and learning

outcomes. Moreover, increased globalization and its effects on the socio-cultural and

economic dynamics of countries has given researchers reason to believe there will arise a

shift in the demand for foreign language learning, hitting monolingual speakers the

hardest. An integrative approach is suggested to be most effective for language

instruction and could be used to better serve students and those traditionally disengaged

from languages as a whole. The context of this study takes place among a population that

is primarily monolingual in English, therefore it would be expected to observe a number

of the trends listed in the review of literature among the results. The next chapter will

discuss the methodology of this study and describe its research questions, participant

population, research design, data collection and analysis procedures, and limitations.

15

METHODOLOGY

As discussed in the previous chapter, motivation and attitude are important factors

influencing success in language acquisition. Competitive advantages stemming from

multilingual ability are predicted to rise as global markets continue growing. This trend

suggests that monolinguals would increasingly view foreign language ability as either a

necessary or desirable trait to possess. A qualitative approach to research has great

potential to descriptively detail reasonings behind why both monolinguals and

multilinguals either seek to engage in language learning or not. The focus of this

investigation will be centered on insights offered by participants on the study of foreign

language with the expectation that findings will reflect ideas discussed in Chapter II.

In their study, Russell and Kuriscak (2015) found it reasonable to expect

multilingual adults to attribute more value and display more positive attitudes towards

foreign language learning than their monolingual peers. This hypothesis can be inferred

on the assumption that multilingual individuals have experienced more exposure and

positive utilization of foreign language(s) than their monolingual counterparts. However,

it is also possible that monolingual adults who have had sufficient positive interaction

with other languages and their respective cultural groups display similar positivity despite

not speaking the language. Equally, there exists the possibility that neither

monolingualism nor multilingualism has any significant influence on one’s personal

stance towards language, but rather a set of other unforeseen factors that may not be

measurable in this study and therefore would remain a topic for further research.

16

Research Questions

Due to this study being exploratory in nature, a qualitative approach was deemed

to be best for investigating the opinions that adult individuals hold towards foreign

language acquisition. Due to the context of this study being situated in higher education,

the overarching question of this study centers on the perceptions of university adults on

foreign language, while the second question narrows the scope to two specific groups to

provide for comparison. The research questions are as follows:

• What perceptions do adult university students display towards foreign language

acquisition?

• Are there any distinctions exhibited in the perceptions between monolinguals and

multilinguals?

Participants

To generate a large enough sample size to provide enough data for adequate

comparison, the participants of this study only need be self-selected adult individuals

willing to complete an online survey. To fulfill the “adult” context of this study, all

participating individuals must be 18 years or older—the only requirement for

participation. It was the hope of the researcher that naturally, a substantial number of

people would answer the survey who would either by default be monolingual or happen

to be multilingual, thereby offering enough data for comparison between the two. To

distribute the survey most efficiently, a mailing list of all enrolled undergraduate and

graduate students at The University of Southern Mississippi was used.

17

Research Design

A mixed-methods approach was selected as the most appropriate design for this

study’s investigation. Although the purpose of this study heavily centers on the

qualitative aspects of collected results, quantitative metrics are useful in being able to

help identify potential trends observed within the qualitative analysis of the data set. A

series of questions and Likert scales were employed to collect information pertaining to

participants’ demographic and linguistic background, as well as their

attitudes/orientations toward foreign language acquisition. Results were then tabulated

and exported for further analysis in MAXQDA.

Qualitative Design and Analysis

Qualitative research can have several variations in its implementation, however a

traditional approach commonly “consists of preparing and organizing the data […] for

analysis; then reducing the data into themes through a process of coding and condensing

the codes; and finally representing the data in figures, tables, or discussion” (Creswell &

Poth, 2018, p. 183). This study follows the “data analysis spiral” approach illustrated by

Creswell and Poth (2018), and consists of five main steps (pp. 185–198):

• Managing and organizing data

• Reading and memoing emergent ideas

• Describing and classifying codes into themes

• Developing and assessing interpretations

• Representing and visualizing data

Effective storage, organization, and management of data is imperative for

increased ease of analysis conducted by the researcher. Once organizational methods are

18

decided upon, one can begin to engage in the analysis process by becoming familiar with

the dataset through preliminary reading and scanning of text that allows the researcher to

“build a sense of the data as a whole without getting caught up in the details of coding”

(Creswell & Poth, 2018, p.188). In the meanwhile, it is suggested to create and prioritize

“memoing” throughout the entire analytic process to help keep track of the development

of ideas that may emerge within the researcher that may guide adjustments made in the

classification and/or interpretation phase (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 189). The next step

in the data spiral approach is to engage in coding procedure that will provide a foundation

for later thematic analysis.

Coding allows for the identification and interpretation of prevalent ideas among

the dataset that should allow for later classification into themes by the researcher. A

common way to approach coding is to begin with detailed description or descriptive

coding that summarizes what the researcher clearly observes among the text (Creswell &

Poth, 2018, p. 189; Saldaña, 2016, p. 102). Working in tandem with description,

“prefigured” coding, also known as “provisional coding,” stems from preparatory

investigation and can be “revised, modified, deleted, or expanded to include new codes”

as data continues to be analyzed (Saldaña, 2016, p. 168). While the number and types of

codes one chooses to use can vary and should be best suited to what the researcher

intends to measure, Creswell and Poth (2018) suggest “lean coding” that later “expands

as review and re-review of the database continues” (p. 190). This approach is meant to

make the proceeding process of theme classification easier and engage in the practice of

actively “winnowing” data to reduce review and use of redundant answers (Wolcott,

1994 as cited in Creswell and Poth, 2018, p. 190). Once adequate application of codes

19

has been completed after several rounds of review, one can begin the classification of

information contained in codes into broader themes.

Classification of themes requires aggregating several codes into a common idea

with the intent of generating several themes (or categories) that characterize the entire

dataset (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 194). From grouping codes into themes and themes

into larger units of categorization, a researcher may begin to engage in abstracting

beyond what is simply stated in codes and themes to find “the larger meaning of the data”

(Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 195). As Creswell and Poth (2018) discuss in greater detail,

approaches through which interpretation of data takes place depend on the form and

interpretative framework the researcher chooses to employ. The two main outcomes they

propose should arise from this assessment phase of the analytic spiral process are (p.

187):

• Contextual understandings and diagrams

• Theories and propositions

Lastly, it is up to the researcher to choose an appropriate method to represent findings

produced from this final phase of assessment and interpretation.

Theoretical Issues

Several issues arise when determining how to approach coding qualitative data, of

which Creswell and Poth (2018) highlight four main ones: the question of whether codes

should be counted (numerically), the use of preexisting codes, origin of code names, and

the type of information a researcher codes (pp. 192–194). The ability of preliminary

counts and code frequencies to be reported by researchers is something of a debatable

topic regarding how relevant it should be in qualitative research. Many see reporting code

20

frequency as inconsequential to a qualitative study, meanwhile Creswell and Poth (2018)

suggest taking into consideration code counts but not reporting it in the final study due to

them viewing numerical emphasis as being “contrary to qualitative research,” conveying

the ideas that all codes are equal, and disregarding the possibility that coded passages

could in actuality “represent contradictory views” (pp. 192–193). As discussed

previously, this study produces code lists that contain provisional, as well as “emergent”

elements; however, over-reliance on prefigured codes has the danger of limiting analysis

to content contained in previous literature rather than emphasizing what the data may

reveal itself (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 193). Codes can be named in a variety of ways

based on the approach and perspective of the researcher and therefore must be carefully

determined to reflect accurate and credible interpretation of data. As Saldaña (2016)

notes in his explanation of Values Coding, a “researcher is challenged to code [a]

statement any number of ways depending on the researcher’s own systems values,

attitudes, and beliefs” (p. 135); therefore, great care must be taken to mitigate any

extreme biases a researcher may carry when participating in the analysis process. Lastly,

there are several data analysis strategies one could utilize when reviewing qualitative data

that may tend to highlight one type of content while overlooking another based on what

the researcher is looking to code. Examples Creswell and Poth (2018) provide reference

data material pertaining to different research types such as narrative, phenomenological,

grounded theory, ethnography, and case study (p. 193).

Validation and reliability are two important quality criteria that have traditionally

been the standard all quantitative research must meet to be considered legitimate;

however, the way these criteria translate in qualitative research is different from

21

quantitative contexts and has several proposed perspectives for what such criteria should

be (Creswell & Poth, 2018, pp. 254–259). Creswell and Poth (2018) highlight intercoder

agreement as a method of ensuring reliability that requires multiple individuals to code

and analyze the same data sets with the goal of meeting a certain threshold of agreement

(pp. 264–266). Due to the nature of this research project being an undergraduate honors

thesis, such intercoder and other triangulation methods were neither available nor feasible

for the researcher to employ in this study. Therefore, it should be known that the creation,

classification, and interpretation of all codes and themes in this study was at the complete

discretion of the single researcher. Coupled with lack of triangulation methods, a single

coder, analyzer, and interpreter inherently increases the element of researcher bias in this

study. To combat this, disclosure of researcher bias and increased reflexivity provides for

increased transparency that may bolster trust in the researcher as an actor with integrity

(Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 261). Such disclosure will be provided in the following

section.

It should be known that the researcher of this study is an undergraduate world

language (Spanish) student who is bilingual. The researcher acknowledges her positive

disposition towards foreign languages and generally perceives the benefits of foreign

language learning, proficiency, exposure, exchange, etc. to outweigh its costs in most

respects. Due to being considered bilingual herself, the researcher expects overlap

between beliefs/opinions expressed by multilingual respondents of this study and her own

to be present. She is aware of the increased likelihood of being able to more easily

identify elements of respondents’ answers that confirm her preconceived notions of each

lingual group based on information from previous research literature combined with her

22

own personal experience. Aware of this bias, the researcher was purposeful in

formulating the focus of this study and its research questions to be more descriptive in

nature rather than explanatory, although certain interpretations will be proposed only as

considerations in Chapter IV. Moreover, none of the statements utilized in the survey

stem from the researcher’s own beliefs, but rather were taken either from pre-existing

items of literature or created with the intent to measure an aspect of perception based on

general findings in previous research literature.

Data Collection Procedures

This study utilized an electronic survey created through Qualtrics and was

estimated to take at least 15 minutes to complete. Skip-logic was used in the design of the

survey to allow for seamless and efficient presentation of relevant prompts to the user.

The survey was mass distributed through university email to all undergraduate and

graduate students who attend the University of Southern Mississippi. The survey was

published and actively open online for a period of one week between July 8

th

, 2022–July

15

th

, 2022. Consent to participation was implied by completion of the survey. Those who

did not wish to participate were instructed not to proceed with the survey and close their

browser. All participants who completed the survey remained anonymous and the use of

direct quotes does not contain personal identifiers. All data from the survey was

tabulated, visualized, and exported from Qualtrics as either a default report or to

Microsoft Excel for data cleaning. After data was organized, it was then imported to

MAXQDA for coding and thematic analysis.

23

Instrument

An electronic survey consisting of a questionnaire and prompts was employed to collect a

combination of both quantitative and qualitative data from respondents.

Demographic Collection. The survey begins with a Demographic Collection

question set that asks participants to identify their age group, sex, race/ethnicity,

Hispanic/Latino/Spanish origin, education level, and status of familiarity within the

United States. It was preferred that people select the age group to which they belonged to

rather than explicitly list their age as a matter of expediency, and to address the fact that

many participants may have felt discouraged from participating in the questionnaire had

they been required to list their age. The status of familiarity within the U.S. for each

participant refers to the extent one was born and raised in or outside the U.S.; this was

done to later be able to distinguish between those who are native and foreign-born within

both monolingual and multilingual groups and provide categories for potential

comparison. Specific demographic questions can be referenced in Appendix A.

Language Probe. This question set is designed to collect background information

on which languages a participant and their parents speak and whether they have engaged

in language learning either in the past or present. The question set distinguishes whether

participants and their parents are monolingual or multilingual, languages spoken by both

the participant and parents, the participant’s first language(s), and whether they are

learning a foreign language (or have in the past). A language menu was provided for

participants to select which languages applied to their answers, with an “other” text box

offering text input for languages not listed. Data collected from this question set was

used to classify participants as either monolinguals or multilinguals for analysis and

24

comparison. Additionally, this question set is purposed to gather information to help

determine the extent of exposure a participant has had to other language usage and

environments since correlation between exposure and attitude has been suggested to be

important in determining overall perception. For specific questions see Appendix A.

Likert Scales. Adult perception towards foreign language in this study focuses on

the measurement of attitude/orientation, coupled with opinions and beliefs held by

participants. Likert scales are a common instrument used in surveys and questionnaires to

measure distinct grades of attitude and hence, were incorporated into this survey to offer

quantitative data on attitude/orientation. To avoid participants from defaulting to an

indifferent response in the survey, the common “neutral” scale option was removed, and

instead a six-degree ascending scale was used ranging from “strongly disagree” to

“strongly agree”. It was the intention that the removal of a “neutral” option would cause

participants to consider their sentiments more carefully when responding and prevent

excessive inconclusiveness. Likert responses were scored with the lowest degree of

favorability option given a value of 1 and the highest degree of favorability option given

a value of 6. A total of three Likert scale sets were used that provided prompts based on

categorizations of positive, neutral, and negative. Statements are classified under

category types based on their emotional characterization regarding languages and

language learning. All sets were scored 1–6 with “strongly disagree” given a value of 1

and “strongly agree” given a value of 6 in ascending order. The positive set contained a

total of five statements, the neutral set contained two statements, and the negative set

contained a total of four statements. The mean and standard deviation were calculated for

each Likert statement for the entire data set, and then separately for monolinguals and

25

multilinguals for comparison. Several statements from the Revised Attitude and

Motivational Battery Items List found in the Appendix of the Acheson, et al. study (2015)

were included and are identified in Appendix A of this study. Specific Likert statements

can be referenced in Appendix A.

Extended Response. The survey concludes with an extended response section

designed to collect all qualitative responses from participants and is the focus of this

study. This section includes three selected statements from previous Likert scale sets

(positive, neutral, negative), along with a newly generated fourth, to which an extended

response box was provided for the participant to “elaborate and respond fully to each

statement as [they] wish” (see Appendix A). Statements selected were chosen with the

intention that they would slightly provoke participants’ emotional dispositions. It was the

researcher’s intent that the somewhat biased nature of several extended response

statements, combined with limited choice to express attitude in the previous Likert scale

section, would encourage participants to take advantage of the opportunity to fully

express their thoughts as accurately and extensively as they felt needed. The expectation

was that participants’ answers would reflect elements of concepts such as value,

motivation, priority, confidence, and instrumentality as they pertained to foreign

language acquisition, and monolinguals v. multilinguals that could be descriptively

identified and thematically analyzed. The set concludes with an optional portion where

participants may express any remaining thoughts or opinions regarding foreign language

based on questions and prompts shown to them in the survey, or their own experiences.

26

Data and Analysis

Data organization for this study was done through storage and preliminary

analysis offered in Qualtrics. A default report was generated and exported for the

reporting of information from the demographic collection and language probe question

sets. Data collected from Likert scales was used to calculate the mean and standard

deviation of every Likert scale item for all respondents, all monolinguals, and all

multilinguals. The mean and standard deviation were used to compare averages and

dispersion of sentiments between each group. The statistical significance for each item of

these groups was not calculated and used for analysis since this study prioritizes focus on

its qualitative findings. All survey information was then exported to Microsoft Excel for

data cleaning to later be exported to MAXQDA. Data cleaning consisted in eliminating

respondents who were not able to complete the survey (those younger than 18 years),

those who did not answer any extended response prompts (“N/A,” invalid text, etc.), and

redundant variable information. After cleaning, the respondents’ survey information was

imported into MAXQDA, where the analysis focus was centered on the last five extended

response statements of the survey for each respondent.

The next step was to briefly review all extended response statements to allow the

researcher to familiarize herself with the data set and begin the coding process. Answers

that yielded little to no descriptive information such as “yes,” “no,” “agree,” “I guess”

were moved to a miscellaneous folder to reduce the reading load and direct attention to

answers that contained more detail from respondents. Quick scanning allowed for the

identification of common ideas prevalent among responses and aided in generating a

preliminary list of codes for each prompt used in later rounds of coding beginning with

27

descriptive coding (Saldaña, 2016, p. 102). All responses for the first prompt were read

and assigned a descriptive code from the preliminary list that matched its content. If upon

reading through responses, other ideas not found on the preliminary list emerged, a new

code was generated and applied to all applicable answers upon the next round of review.

This process of using both “prefigured” and “emergent” codes upon several rounds of

review allowed for the identification of themes inspired from previous research literature

(“prefigured”), while still providing room for views of participants to be reflected

(“emergent”) (Crabtree & Miller, 1992 as cited in Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 193). The

use of “memoing” was useful in helping track the development of other concepts outside

the focus of the study that could potentially be explored for further research. From

“memoing,” other codes were generated that were either added or replaced those created

on the preliminary list. Preliminary codes that were originally created upon initial review

but later proved to be redundant were also removed. As rounds of analysis continued,

code lists were steadily revised until all answers for every prompt had been reviewed and

most descriptively coded.

The next step was to identify common criteria for which codes could begin to be

categorized into themes for each prompt. The categorization process was identical for all

five prompts with some codes being categorized under others to become sub-codes and

main codes being grouped together based on some commonality in their topic and/or

content to create main themes. The ideas contained within each theme were thoroughly

explained, in addition to the reasons why codes and themes were categorized as they

were by the researcher. After several rounds of classification, all themes created were

then analyzed and categorized once more to produce four master themes that would be

28

used to summarize and characterize the content of the entire extended response data set.

These four themes were then arranged to create a theoretical model the researcher

believed was most appropriate for illustrating the thought process of respondents

regarding how they perceive and produce conclusions about foreign language learning

and acquisition. This theoretical model and content contained within themes and their

codes seeks to answer the first main research question of this study:

• What perceptions do adult university students display towards foreign language

acquisition?

However, to adequately answer the second research question regarding whether any

distinctions exist between monolinguals and multilinguals, further qualitative comparison

had to be conducted.

Crosstabulation and Interactive Quote Matrix functions in MAXQDA were

utilized by the researcher to effectively separate and compare extended response data of

monolinguals and multilinguals. Crosstabulation allows for the comparison of code

frequencies between selected groups activated by document variables. The researcher

chose to compare code frequencies between the two groups by percentage to be able to

identify whether there were any descriptive concepts mentioned significantly more by

one group than the other in proportion to their total number of codes assigned. Codes

with significant percentage differences between the two groups were flagged so that the

researcher could then utilize the Interactive Quote Matrix to individually review answers

provided by monolinguals and multilinguals in a side-by-side comparison. Despite

reviewing flagged codes, only some contained notable differences in content provided by

the two groups while others did not. Regardless, a final side-by-side review and

29

comparison for every code from all extended response answers was conducted using the

Interactive Quote Matrix function. When respondents from both the monolingual and

multilingual groups expressed by majority the same types of ideas for a particular (code),

the researcher would note this sameness in a master chart. However, when either group’s

answers revealed significant nuances or notable differences from the other, such

observation was noted and a summary developed for the specific code and group in the

master chart as well.

The final stage in the analytic process was to compare findings from the

qualitative and quantitative methods employed in this study to evaluate whether they

either corroborate or contradict observations found in the other. Corroboration by

quantitative findings would provide strong suggestion of accurate qualitative analysis and

interpretation by the researcher. Contradiction, on the other hand, would not necessarily

disprove qualitative observation and interpretation of data, but instead might highlight

potential variables not accounted for by the study’s research design and analysis methods.

Such variance may provide for discussion on strengths and weaknesses of each research

method, potential variables not considered, and suggestions for further research to help

clarify and improve potential shortcomings of this study.

Limitations of the study

Aside from theoretical limitations revealed in the research design of this study,

several other limitations arose during the preparation and execution of this investigation

that warrant address. The first is that the population from which the data set of this study

is derived is only a sample representative of mostly a university demographic. Therefore,

results from this investigation only provide description for the several hundred who

30

participated in the survey but are not necessarily representative of adult populations from

other university groups and potentially even less so from other geographic areas

(Hattiesburg, MS versus other U.S. locations). In terms of reliance on the method of self-

reporting, a common limitation is that social desirability bias may influence the level of

honesty participants are willing to offer and result in inconsistencies between what is

internally felt and externally reported by participants despite guarantees of anonymity

and confidentiality (Dörnyei, 1994; Wesely, 2012 as cited in Acheson et al., 2015, p.

212). While numerous challenges exist in attempting to accurately measure attitude, this

study simply did not have the tools to account for all controls and is something that

further research could account for in its research design.

One great challenge of qualitative research is determining the best method(s) to

obtain the best type of information suited for the study’s research question and whether

such methods are feasible for the researcher to execute. This investigation was originally

designed to allow for follow-up with respondents who consented to a brief interview for

elaboration on their survey responses. Interviewing participants would have allowed for

more insight into respondents’ answers and overall perspective. Moreover, it would have

added an interpersonal element to a study that, for the most part, is removed from human

interaction. Due to time constraints and lack of clear criteria for participant selection by

the researcher, it was determined that the interview element of the study was to be

eliminated if the project timeline was to be maintained and enough attention given to

extended response answers provided in the survey.

In sum, theoretical issues of this study that have been addressed include

subjectivity of qualitative coding, lack of triangulation methods, researcher bias,

31

generalizability limits, time constraints, and the potential effect of social desirability bias

on participants. Subjectivity of both participant and researcher is bound to manifest itself

in some form in the research process; however, measures can be taken to increase

transparency in procedures, analysis, and interpretation through qualitative forms of

validity and reliability strategies. Time constraints were the greatest challenge for the

researcher to handle when engaging in data collection, organization, management, and

analysis. Nonetheless, procedures were able to be adjusted to accommodate for changes

in timeline that still fit within the intended mixed-method framework. The next chapter

will present survey results beginning with quantitative collection and then transition to

the main qualitative portion.

32

RESULTS

The electronic survey designed for this study recorded data from 514 respondents,

of which 506 successfully completed the survey. All demographic data collected was

exported from Qualtrics as a default report and is presented in Table sets 1–3. Table items

with an asterisk indicate that multiple answer selection was applicable for the question.

For specific survey details, see Appendix A.

Quantitative Analysis

Demographic Information

Age categories as reported by participants show 18–24-year-olds making up the

largest percentage (43%), with 32–38-year-olds the second largest group (16%), followed

by 25–31year-olds (15%), 39–45-year-olds (12%), and those between 46–50 and over

being the smallest age categories (6% & 9%). Respondents were overwhelmingly women

(70.75%), white (62.85%), and non-Hispanic/non-Latino (93.87%), with most born and

raised in the United States (91.11%). It is not surprising that the educational background

of participants reflects that of a university sample since this is the context in which the

study takes place with a majority of respondents either completing or having completed a

bachelor’s degree (37.94%), master’s degree (23.32%), or doctoral degree (17.19%) as

the top three categories.

Table 1.1. Demographic Information of Respondents

Category

Percentage

Frequency

Age Group

18-24

43%

216

25-31

15%

76

33

Table 1.1. (continued)

32-38

16%

80

39-45

12%

60

46-50

6%

28

Over 50

9%

46

Sex

Male

27.47%

139

Female

70.75%

358

Prefer not to say

0.79%

4

Other

0.99%

5

Race

White

62.85%

318

Black

26.28%

133

Asian

1.78%

9

Native-American

0.59%

3

Mixed Race

5.34%

27

Prefer not to say

1.19%

6

Other

1.98%

10

Hispanic/Latino Origin

Hispanic/Latino

5.34%

27

Non-Hispanic/Non-Latino

93.87%

475

Prefer not to say

0.79%

4

Educational Background

High School GED

1.19%

6

High School Diploma

12.65%

64

Bachelor’s Degree

37.94%

192

Master’s Degree

23.32%

118

Doctorate Degree/PhD

17.19%

87

Other

7.71%

39

U.S. Status

I was born and raised in the U.S.

91.11%

461

I was born and raised outside the U.S.

5.14%

26

I was born outside the U.S. but raised in

the U.S.

1.98%

10

I was born in the U.S. but raised outside

the U.S.

0.40%

2

Other

1.38%

7

34

Over three-fourths of respondents are monolingual (77.08%), while 22.92% of

respondents identified themselves as individuals who speak two or more languages.

Because this survey is only offered in English, it was assumed that anyone who could

understand this survey and is monolingual would naturally be a monolingual anglophone;

this assumption was proven correct in 100% of monolingual respondents reporting

English as the only language they speak for which there is not a table to reflect this

information. Meanwhile, multilinguals reported a diverse array of languages spoken, with

English (40.88%) Spanish (22.99%), French (11.31%) as the top three. Other languages

listed by multilinguals not originally included were Japanese, Thai, Bicolano, Nepali,

Farsi, Yoruba, Igbo, Twi, Ga, Akan, Farsi, Swahili, Mandinka, Romanian, Bulgarian,

Polish, Yiddish, and Kiowa. American Sign Language was another language mentioned

by several not originally considered by the researcher. Of languages learned first by

multilinguals, English (68.22%) was by far the most selected answer with Spanish

(13.95%) following as the second most selected choice.

Table 1.2. Language Background of Respondents

Category

Percentage

Frequency

Monolingual & Multilingual Count

One

77.08%

390

Two or more

22.92%

116

All Participants Currently Learning a

Foreign Language

Yes

26.09%

132

No

73.91%

374

All Participants Who Have

Attempted to Learn a Foreign

Language in the Past

Yes

93.03%

347

No

6.97%

26

35

Table 1.2. (continued)

Languages Spoken by Multilinguals*

English

40.88%

112

Spanish

22.99%

63

French

11.31%

31

Tagalog

1.46%

4

Mandarin

1.09%

3

Vietnamese

0.73%

2

Arabic

1.46%

4

Korean

1.09%

3

Russian

0.73%

2

German

2.29%

8

Italian

1.46%

4

Portuguese

2.19%

6

Other

11.68%

32

Order of Languages Learned for

Multilinguals*

English

68.22%

88

Spanish

13.95%

18

French

2.33%

3

Tagalog

1.55%

2

Arabic

1.55%

2

Russian

0.78%

1

German

1.55%

2

Italian

0.78%

1

Other

9.30%

12