Cybersecurity Governance in the

Commonwealth of Virginia

A CASE STUDY

December 2017

1

Virginia Fast Facts

1

,

2

ELECTED OFFICIALS:

Governor Terry McAuliffe

Virginia House of Delegates:

100 Delegates

Senate of Virginia: 40 Senators

STATE CYBERSECURITY EXECUTIVES:

Secretary of Technology Karen Jackson

Chief Information Officer (CIO)

Nelson Moe

Chief Information Security Officer (CISO)

Mike Watson

3

STATE DEMOGRAPHICS:

Population: 8,100,653

Workforce in “computers and math”

occupations: 4.8%

EDUCATION:

Public with a high school diploma: 45.3%

Public with an advanced degree: 42.2%

COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES:

23 community colleges

16 public universities

96 private or out-of-state institutions

certified to operate in Virginia

KEY INDUSTRIES:

Food Processing

Aerospace

Plastics and Advanced Materials

Data Centers

Information Technology

Cybersecurity

Life Sciences

Automotive

Energy

2

Executive Summary

The Overall Challenge:

How to address a range of cybersecurity challenges that cut across

multiple government, public, and private sector organizations?

Overall Lessons Learned from Virginia’s

Governance Approach:

Leadership Matters. Leaders across multiple government,

public, and private organizations make cybersecurity, and

cybersecurity governance, a priority.

Leadership Is Not Everything. Laws, policies, structures, and

processes instantiate and align cybersecurity governance with

the cybersecurity priority so that focus does not change as

personalities change.

Governance Crosses Organizational Boundaries. The

distributed nature of cybersecurity requires a range of

governance mechanisms that connect across multiple

organizations and sectors.

This case study describes how the

Commonwealth of Virginia (the

Commonwealth) has used laws, policies,

structures, and processes to help govern

cybersecurity as an enterprise-wide, strategic

issue across state government and other public

and private sector stakeholders.

It explores

cross-enterprise governance mechanisms used

by Virginia across a range of common

cybersecurity areas—strategy and planning,

budget and acquisition, risk identification and

mitigation, incident response, information

sharing, and workforce and education.

4

This case study is part of a pilot project intended

to demonstrate how states use governance

mechanisms to help prioritize, plan, and make

cross-enterprise decisions about cybersecurity.

It offers concepts and approaches to other

states and organizations that face similar

challenges. As this case covers a broad range of

areas, each related section provides an overview

of the Commonwealth’s governance approach,

rather than a detailed exploration. Individual

states and organizations seeking greater detail

would likely need to engage directly with the

Commonwealth to better understand how to

tailor solutions to their specific circumstances.

In recent years, the Virginia executive and

legislative branches have taken a series of

deliberate steps to govern cybersecurity as an

enterprise-wide strategic issue across both state

government and a diverse set of private and

public sector organizations. (In this case study,

“agency” refers to executive branch agencies.)

In 2003, the General Assembly passed major

legislation consolidating information technology

(IT) services from across the Commonwealth

into one agency—the Virginia Information

Technology Agency (VITA).

5

VITA is led by the

Chief Information Officer (CIO), who works with

3

a Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) to

address cybersecurity issues.

6

VITA is charged

with overseeing the Commonwealth’s IT

infrastructure, including establishing

information security programs, for the executive

branch departments and agencies. VITA also

oversees IT investments and acquisitions on

behalf of state departments, agencies, and

institutions of higher learning.

The Commonwealth also utilizes a range of

governance structures and processes to address

a variety of cybersecurity challenges that require

collaboration and coordination across public

and private stakeholders. For example, the

Commonwealth approached cybersecurity

strategic planning in a collaborative manner,

inviting public and private stakeholders together

in two different structures created by law. In

2014, Governor Terry McAuliffe created the first

structure, called the Virginia Cyber Security

Commission (the Commission), via Executive

Order 8.

7

The Commission, co-chaired by

Richard Clarke and Secretary of Technology

Karen Jackson, was comprised of public and

private sector experts, including the Secretaries

of Commerce and Trade, Public Safety and

Homeland Security, Education, Health and

Human Resources, Veterans and Defense

Affairs, and 11 citizens appointed by the

Governor. The citizens represented private

industries such as a global credit card company,

a large law firm, and defense and aerospace

companies. The Commission members

developed a set of 29 recommendations: to

improve the resilience and protection of the

Commonwealth’s information systems; invest in

cyber education and workforce development;

increase public awareness of cybersecurity as an

issue worthy of prioritization and investment;

sustain and expand economic development of

cyber-related industries; and modernize state

laws to address cybercrimes (see Section VII for

more details).

8

These policy recommendations

have influenced a range of investment and

programmatic priorities for the state.

The Commonwealth also utilizes several intra-

governmental, cross-agency advisory groups,

councils, and working groups to identify laws

and policies that may need to change to align

with the Commonwealth’s cybersecurity risk

management approach. For example, the Cyber

Response Working Group (CRWG) is a cross-

agency working group focused on planning and

preparation for cyber incidents that could

negatively impact the public’s safety. Originally

formed by the Virginia National Guard (VANG) to

examine how the Guard could support Virginia’s

cybersecurity efforts, the CRWG has since

expanded in scope to oversee initiatives such as

the creation of Virginia’s first Cyber Incident

Response Plan. Members of the CRWG include

the Office of Public Safety and Homeland

Security, VANG, Virginia Department of

Emergency Management (VDEM), VITA, the

Virginia State Police (VSP), and the Virginia

Fusion Center (VFC).

To facilitate information sharing with the private

sector, the Virginia Cyber Security Partnership

(VCSP), a partnership between VITA and the

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) with

approximately 220 private sector entities (such

as major critical infrastructure owner/operators,

retailors, and healthcare providers, among

others), and the public sector (see Figure 3 in

Section V for an overview of membership).

9

The

purpose of the VCSP, created in March 2012, is

to establish a trusted environment where public

and private entities can share cyber threat

information. The VCSP gathers cyber

professionals from across industries in a trusted

environment to share information and lessons

learned about topics such as threat intelligence,

credential management, and supply chain

security.

10

The VCSP includes three

advisors/liaisons: the FBI, the VITA CISO, and a

representative from a large power company.

11

To address the need for a skilled, cyber-ready

workforce, the Commonwealth initiated a

partnership between the state, academia, and

the private sector to develop the Virginia Cyber

4

Range (Cyber Range). The Cyber Range is a

virtual, cloud-based environment designed to

enhance cybersecurity education in Virginia’s

high schools, colleges, and universities.

12

The

Cyber Range is operated within Virginia

Polytechnic Institute and State University

(Virginia Tech) and is “led by an executive

committee representing public institutions that

are nationally recognized centers of academic

excellence in cybersecurity within the

Commonwealth of Virginia.”

13

Cybersecurity is a challenge that cuts across

many issues and many interdependent

stakeholders. The Commonwealth uses a range

of governance mechanisms to work across

different public, private, academic, and

nonprofit organizations. Leadership on the part

of individuals, including the Governor and the

legislature, who made cybersecurity and

cybersecurity governance a priority across

government, public, and private organizations

was very important. However, leadership was

not everything. As the Commonwealth

illustrates, the priority was translated into

tangible laws, policies, structures, and processes

that aligned cybersecurity governance with

broader cybersecurity priorities.

5

Table of Contents

Virginia Fast Facts ......................................................................................................................................... 1

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 2

Background & Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 6

I. Strategy & Planning ................................................................................................................................... 7

II. Budget & Acquisition ................................................................................................................................ 9

III. Risk Identification & Mitigation ............................................................................................................. 11

IV. Incident Response ................................................................................................................................. 14

V. Information Sharing ............................................................................................................................... 17

VI. Workforce & Education ......................................................................................................................... 20

VII. Deep Dive: Virginia Cybersecurity Commission ................................................................................... 22

VIII. Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................. 24

6

Background &

Methodology

This case study was developed as part of a pilot

project to identify how states have used laws,

policies, structures, and processes to help better

govern cybersecurity as an enterprise-wide,

strategic issue across state government and

other public and private sector stakeholders.

This project emerged as a result of the

Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

Advisory Council Final Report of the

Cybersecurity Subcommittee, Part II – State,

Local, Tribal & Territorial (SLTT), which

recognized the importance of governance in

addressing a range of cybersecurity technology

and operational challenges.

14

The case study explores cross-enterprise

governance mechanisms used by Virginia across

a range of common cybersecurity areas—

strategy and planning, budget and acquisition,

risk identification and mitigation, incident

response, information sharing, and workforce

and education. It is not intended to serve as a

formal evaluation. Instead, the case offers

concepts and approaches that may be useful to

other states and organizations that face similar

challenges. As this case covers a broad range of

areas, each related section provides an overview

of Virginia’s governance approach, rather than a

detailed exploration. Individual states and

organizations seeking greater detail would likely

need to engage directly with Virginia to better

understand how to tailor solutions to their

specific circumstances.

DHS’ Office of (CS&C) Cybersecurity and

Communications initiated and leads the project

in partnership with the National Association of

State Chief Information Officers (NASCIO).

NASCIO is a nonprofit association “representing

state chief information officers and information

technology executives and managers from the

states, territories, and the District of

Columbia.”

15

The Homeland Security Systems

Engineering and Development Institute

(HSSEDI), a DHS owned Federally Funded

Research and Development Center (FFRDC),

developed the case studies.

Candidate states were identified to participate

in the pilot project based on:

analysis of third party sources,

diversity of geographic region, and

recommendations from DHS and NASCIO

with awareness of SLTT cybersecurity

practices.

Candidate states that agreed to participate in

the DHS-led pilot project did so on a voluntary

basis. Researchers used open source material

and conducted a series of interviews to gather

the necessary information to develop each state

case study.

7

I. Strategy & Planning

The Challenge:

How to set direction and prioritize cybersecurity initiatives across

multiple organizations?

Features of Virginia’s Governance Approach:

The Commonwealth centralizes cybersecurity strategy and

planning activities under the Secretary of Technology and the

state Chief Information Officer (CIO).

The Commonwealth uses intra-agency working groups and

councils as well as private sector advisory groups to help

prioritize actions to address cybersecurity risks.

The Governor created a temporary structure via executive

order—the Virginia Cyber Security Commission—comprised of

public and private stakeholders to study and make

recommendations to improve the Commonwealth’s overall

cybersecurity posture.

The Commonwealth uses several governance

mechanisms to bring multiple public and private

stakeholders into the strategy and planning

process and drive cross-enterprise strategy.

Commonwealth government cybersecurity

strategy and planning activities are centralized

by law under the Secretary of Technology, who

oversees VITA, and to whom the state’s CIO

reports.

16

The law directs the Secretary of

Technology to “review and approve the

Commonwealth strategic plan for information

technology,” which is developed and

recommended by the CIO and includes

cybersecurity activities.

17

The CIO collaborates

with and collects inputs from the CIO Council’s

Customer Advisory Council, “a workgroup of

agency technology representatives, and IT

subject matter experts,” to draft the strategic

plan.

18

The 2014-2016 strategic plan sets the overall

direction and “establishes the basis for the

scoring, ranking and evaluation process to

ensure alignment of proposed IT investments to

the Commonwealth vision” which, in turn,

“determines whether the commonwealth CIO

approves or disapproves the IT investments.”

19

The Commonwealth’s vision is to leverage

technology to enable “far-reaching business

solutions that benefit all constituents.”

20

In the

CY2017 update to the 2014-2016 strategic plan,

cybersecurity is reflected in two of the six

priorities:

1. Move to cloud application hosting,

2. Provide secure wireless access within

state office buildings for employees and

the public,

3. Provide greater internet access and

bandwidth to meet demand,

4. Support delivery of critical digital

services to agencies and constituents,

8

5. Implement IT infrastructure transition

successfully, and

6. Implement shared security services

(assist agencies with identifying and

managing security needs via shared

services such as Centralized Information

Security Officer, Centralized IT Security

Audit, and the Security Incident

Management).

21

The CIO considers these six priorities when

evaluating IT investment requests from the

Commonwealth’s agencies and departments.

Investment proposals need to align with the

strategic plan’s vision and stated IT priorities to

obtain CIO approval.

The Commonwealth also uses advisory councils

and commissions to inform cybersecurity

priorities. The law directs the Secretary of

Technology to engage with a variety of agencies,

councils, and boards in setting strategy and

direction. They include the Information

Technology Advisory Council (ITAC).

22

The ITAC

is an advisory council within the executive

branch of state government and is “responsible

for advising the CIO and the Secretary of

Technology on the planning, budgeting,

acquiring, using, disposing, managing, and

administering of information technology in the

Commonwealth.”

23

The ITAC, which includes

membership from across government and the

private sector, advises and influences the

Commonwealth’s strategy to address

cybersecurity issues.

In 2014, the Commonwealth approached

cybersecurity strategic planning in a

collaborative manner, inviting public and private

stakeholders together in two different

structures created by law. The Governor created

the Virginia Cyber Security Commission (the

Commission), via Executive Order 8.

24

The

Commission, co-chaired by Richard Clarke and

Secretary of Technology Karen Jackson, was

comprised of public and private sector experts,

including the Secretaries of Commerce and

Trade, Public Safety and Homeland Security,

Education, Health and Human Resources,

Veterans and Defense Affairs, and 11 citizens

appointed by the Governor. The citizens

represented private industries such as a global

credit card company, a large law firm, and

defense and aerospace companies.

The Commission members developed a set of

recommendations to improve the resilience and

protection of the Commonwealth’s information

systems; invest in cyber education and

workforce development; increase public

awareness of cybersecurity as an issue worthy of

prioritization and investment; sustain and

expand economic development of cyber-related

industries; and modernize state laws to address

cyber crimes.

25

Secretary of Technology Karen

Jackson characterized the Commission’s

recommendations and report as a “game

changer” for those advocating for changes in law

to support cybersecurity-related investments,

describing it as a “grounding document” that

influenced decisions on budget, policy, and the

law.

26

For example, recommendations related to

education and workforce development led

directly to the creation of the Cyber Range and

the Virginia Cybersecurity Public Service

Scholarship Program, which awards $20,000 per

year, for up to two years, to eligible Virginia

students studying cybersecurity.

27

The

Commission has seen many of its

recommendations implemented since 2016 and

continues to influence executive and legislative

actions today.

9

II. Budget & Acquisition

The Challenge:

How to manage investments in strategic cybersecurity priorities as

part of budget and acquisition processes across multiple

organizations?

Features of Virginia’s Governance Approach:

IT budget requests from state departments and agencies are

reviewed and approved by the CIO and Chief Information

Security Officer (CISO) to ensure adherence to cybersecurity

priorities, policies, and standards.

Central acquisition processes are used to manage cybersecurity

risks and ensure that cybersecurity requirements are adopted

across government agencies.

Standard vendor contract language is used to ensure adherence

to information security standards.

The Commonwealth uses its budget and

acquisition governance processes to drive cross-

government implementation of cybersecurity

standards and priorities. The Commonwealth

provides state funding through the annual

budget process (called the Governor’s budget

bill). While departments and agencies each

receive their own IT budget on an annual basis,

budget requests for IT projects, including those

that may introduce cyber risks to the

Commonwealth’s enterprise, are overseen by

the CIO, with consultation from the CISO. The

CIO ensures that budget requests and

acquisitions are aligned with the

Commonwealth’s IT strategic direction and with

cybersecurity policies and standards developed

by the CISO.

10

Figure 1. High-Level Overview of Annual Commonwealth Budget

Processes Related to Cybersecurity Funding

As shown in Figure 1, the law directs

departments and agencies to provide the CIO

with justification for IT projects, including cyber

investments, as part of the Governor’s budget

bill.

28

The CIO reviews agency requests for cyber

investments as part of the annual budget

process and has the authority to approve or

disapprove them. This means that agency and

department requests for IT projects, including

proposed acquisitions for products/services

from outside vendors, must adhere to IT security

standards set by the CISO. And the CIO reviews

proposed projects to ensure adherence to

current IT policies and standards. According to

CIO Nelson Moe, “the advantage in Virginia is

that the state is consolidated”—all agency

procurement comes through VITA, which, in

turn, allows the CIO to manage cybersecurity

risks associated with vendor products and

services.

29

The Commonwealth intentionally designed the

acquisition process to ensure that all outside

vendors adhere to cybersecurity standards.

First, the Commonwealth has a single vendor

contract in place with Northrop Grumman to

provide the bulk of IT products and services,

including cybersecurity services, for all state

departments and agencies. Most IT services and

products for the Commonwealth’s IT

infrastructure are provided through this

contract, allowing the CIO to enforce and

manage cybersecurity standards across the

Commonwealth’s enterprise. The CIO manages

the vendor contract and requests to purchase

goods and services outside of the contract. If a

department or agency requests a product or

service outside of the contract, there is an

extensive process to vet vendors to ensure that

cybersecurity standards are met. Before an IT

product or service is acquired, “we have a list of

150–200 questions we ask vendors to respond

to,” said Commonwealth CISO Mike Watson.

30

All acquisition exception requests must meet

cybersecurity protocols and be approved by the

CIO.

Second, standard information security contract

language is included in the terms and conditions

of all vendor contracts, including the single

vendor contract. This contract feature ensures

that the Commonwealth works only with

vendors that can provide products and services

that meet the cybersecurity policies and

standards put forth by VITA. The acquisition

process “works well and is flexible to meet

emerging demands for new products or services,

such as cloud services,” Watson said.

31

11

III. Risk Identification &

Mitigation

The Challenge:

How to identify and mitigate cybersecurity risks across multiple

public and private organizations?

Features of Virginia’s Governance Approach:

Risk identification and mitigation functions are centralized in the

Commonwealth through the CIO and CISO, who develop

policies, standards, and guidelines to identify and address cyber

risks in state departments and agencies.

Smaller departments and agencies can access CISO expertise

through a shared services model offered by VITA.

Standing advisory councils that include public and private

representation identify and address cyber risks that go beyond

the state government.

The VITA CIO and CISO lead cyber risk

identification and mitigation functions across

Commonwealth government departments and

agencies. The Commonwealth also utilizes intra-

governmental, cross-agency advisory groups,

councils, and working groups to evaluate laws

and policies that may need to change to align

with the Commonwealth’s risk management

posture.

In 2003, the General Assembly passed major

legislation reorganizing nearly all IT

infrastructure and telecommunications services

across the Commonwealth into one agency—

VITA. The Commonwealth Security and Risk

Management (CSRM) Directorate, a unit within

VITA, is led by the Commonwealth’s CISO.

32

The

CSRM executes many CIO-related risk

identification and audit activities.

33

For example,

the CSRM assesses the strength of

Commonwealth agency and department IT

security programs through regular security

audits. Results of the audits are compiled and

published in an annual Commonwealth of

Virginia Information Security Report. If an

information security audit finds inadequate

security, the CISO discourages the

agency/department from beginning new IT

investments until the information security issues

and risks are remedied.

34

This process helps

ensure that agencies prioritize funds to mitigate

risks prior to receiving additional resources.

In 2014, the Commonwealth adopted the

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Cybersecurity Framework to “enhance the

systematic process for identifying, assessing,

prioritizing and communicating cybersecurity

risks, efforts to address risks, and, steps needed

to reduce risks as part of the state’s broader

priorities.”

35

The Commission (described in

Sections I and V) called on VITA to “evaluate the

12

maturity level of state agencies cyber security

programs and practices by leveraging the

Framework as a means of assessment” on an

annual basis.

36

As part of VITA’s ongoing risk identification and

mitigation responsibilities, the CIO must

“identify annually those agencies that have not

implemented acceptable policies, procedures,

and standards to control unauthorized uses,

intrusions or other security threats.”

37

Noncompliant agencies are identified by

evaluating information security audit, risk, and

threat management programs.

38

CISO Mike

Watson noted, “We have a risk database of all

our findings” detailing the

agencies/departments that fail to meet security

standards.

39

The CISO performs a mid-year

preliminary assessment before the end-of-year

audit, which allows agencies that may not be in

compliance mid-year approximately six months

to address security issues. Lee Tinsley, CIO of the

Department of Veterans Services, said,

“Agencies get on the wall of shame because they

fall out of compliance.”

40

The CISO, agency head,

and agency Information Security Officer (ISO)

then work together to address the issues.

41

The

risk database helps the CISO and CIO track the

risks and ensure that they are remediated over

time. This, in turn, provides the CIO and CISO

situational awareness to ensure compliance

across the state government enterprise.

In addition to ongoing risk management

activities, VITA has undertaken some important

one-time actions. In August 2015, the Governor

signed Executive Directive 6 furthering the

Commonwealth’s risk management of

protected, sensitive data from potential data

breach. The Directive was intended to

“strengthen the Commonwealth’s cybersecurity

measures to protect personal information and

sensitive data” and decrease the risk of data

breach.

42

Per the Directive, VITA conducted an

inventory of Commonwealth data and computer

systems to determine their sensitivity and

criticality and recommended “strategies to

strengthen and modernize agencies’ cyber

security profiles.”

43

The VITA data inventory

revealed that the Commonwealth processes

billions of records each year that contain

sensitive data, such as personally identifiable

information, federal tax information, and

payment card industry data. Moreover, VITA

found that more than 1,000 IT systems across

the Commonwealth’s agencies and departments

store sensitive data. The results of the VITA data

inventory led to several risk management

recommendations to strengthen controls to

protect sensitive data stored on Commonwealth

IT systems and networks. Many of the

recommendations have been, or are in the

process of being, adopted.

Recognizing that not all departments and

agencies are large enough to support a full-time

CISO, VITA offers smaller agencies and

departments access to CISO expertise through a

shared services model. Agencies and

departments can contract with VITA as needed

to obtain assistance with cyber-related

administrative, technical, and/or operational

matters. This service provides needed assistance

without the cost of keeping a full-time CISO on

staff. The shared CISO services model was a

recommendation from the Commission and was

implemented by the VITA.

Standing intra-governmental working groups

are also used to identify cyber risks. The Secure

Commonwealth Panel (SCP), for example, is a

legislatively created standing advisory group

tasked with reviewing and identifying laws and

policies that may need to change to address

public safety and homeland security issues in the

Commonwealth. By statute, the SCP consists of

36 members from the legislative and executive

branches as well as private citizens and is

chaired by the Secretary of Public Safety and

Homeland Security.

44

Recognizing the threat

cyber poses to public safety, the SCP formed the

Cyber Security Sub-Panel to evaluate whether to

amend Virginia’s laws and policies regarding

cyber crime, critical infrastructure, and law

13

enforcement. The Cyber Security Sub-Panel

meets quarterly and is comprised of members of

the Governor’s Cabinet, Virginia’s Legislature,

representatives from a variety of state agencies,

and private citizens.

45

Recommendations are

passed to the Secretary of Public Safety and

Homeland Security and the SCP, who shares

them with the Governor and, where

appropriate, the General Assembly.

As mentioned earlier, the CRWG is a multi-

agency working group focused on planning and

preparation for cyber incidents that could

negatively impact the public’s safety. Originally

formed by the Virginia National Guard (VANG) to

examine how the Guard could support Virginia’s

cybersecurity efforts, the CRWG has since

expanded in scope to oversee initiatives such as

the creation of Virginia’s first Cyber Incident

Response Plan. Members of the CRWG include

the Office of Public Safety and Homeland

Security, VANG, Virginia Department of

Emergency Management (VDEM), VITA, the

Virginia State Police (VSP), and the Virginia

Fusion Center (VFC).

14

IV. Incident Response

The Challenge:

How to prepare for and respond to cyber incidents that require

coordinated action across multiple organizations?

Features of Virginia’s Governance Approach:

VITA leads non-emergency cyber incident response.

A unified command (UC) structure integrates cyber emergency

response with the existing emergency management response.

The cyber UC structure includes VITA, Virginia Department of

Emergency Management (VDEM), Virginia State Police (VSP),

and the affected entity to manage emergency cyber incident

response.

The Commonwealth uses an advisory panel of public and private

stakeholders to regularly assess emergency response activities,

including cybersecurity.

The Commonwealth utilizes laws and policies to

clarify incident response governance. The laws

establish foundational roles, responsibilities,

and processes that all Commonwealth agencies

and departments must follow to report non-

emergency and emergency incidents. These

laws and supporting policies describe what

constitutes a cyber incident, what criteria is

used to evaluate the severity of an incident and

defines the roles and responsibilities of agencies

tasked with resonding to an incident.

VITA defines a cyber incident as an event that

threatens to do harm, attempts to do harm, or

does harm to the system and/or network.

46

A

cyber event “is any observable occurrence in a

system, network, and/or workstation.”

47

Example events include a system crashing and

rebooting, unwanted emails bypassing firewalls

and being delivered, and packets flooding the

network. VITA directs agencies and departments

to record events to determine “the baseline for

normal activity on systems/networks” so that if

events rise to an incident, “corroborating

evidence is available” for investigative and

possible law enforcement purposes to

understand the deviation from the norm. For

example, malware and denial-of-service attacks

are characterized as incidents.

If the cyber incident occurs on the state

network, VITA is the lead agency that manages

the response. The Commonwealth’s IT Incident

Response Policy, which is drafted by VITA,

specifies that all agencies “document and

implement threat detection practices;

information security monitoring and logging

practices; and information security incident

handling practices.”

48

VITA incident response

policy instructs departments and agencies to

conduct incident response tests/exercises at

least once a year “to determine the incident

response effectiveness and document the

results.”

49

VITA also reviews and approves IT

disaster recovery and continuity plans

15

developed and maintained by all executive

agencies.

When cyber incidents occur, agency directors

must, by law, report them to VITA within 24

hours “from when the department discovered

or should have discovered their occurrence.”

50

While department or agency directors track

events to identify the “norm,” there are specific

conditions that trigger an incident that should

be reported to the VITA CIO. VITA specifies that

agencies report incidents that “have a real

impact on your organization” such as “detection

of something noteworthy or unusual (new traffic

pattern, new type of malicious code, specific IP

as source of persistent attacks).”

51

VITA incident

response guidelines specify reportable incidents

to include:

52

An adverse event to an information

system, network, and/or workstation; OR

Exposure, or increase risk of exposure, of

Commonwealth data; OR

Threat of the occurrence of such an event

or exposure.

VITA provides agencies and departments with

an online Information Security Incident

Reporting Form to capture, organize, and

analyze reported incidents from across the

enterprise.

53

The VITA Commonwealth’s

Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT)

categorizes each security incident based on the

type of activity.

54

The VITA Computer Incident Response Team

(CIRT) coordinates all reported incidents from

across the Commonwealth’s agencies and

departments.

55

The CIRT is comprised of the

agency/department ISO and the VITA CSRM

incident management staff. The CIRT, agency

management, and the ISO determine whether

the incident requires an immediate response.

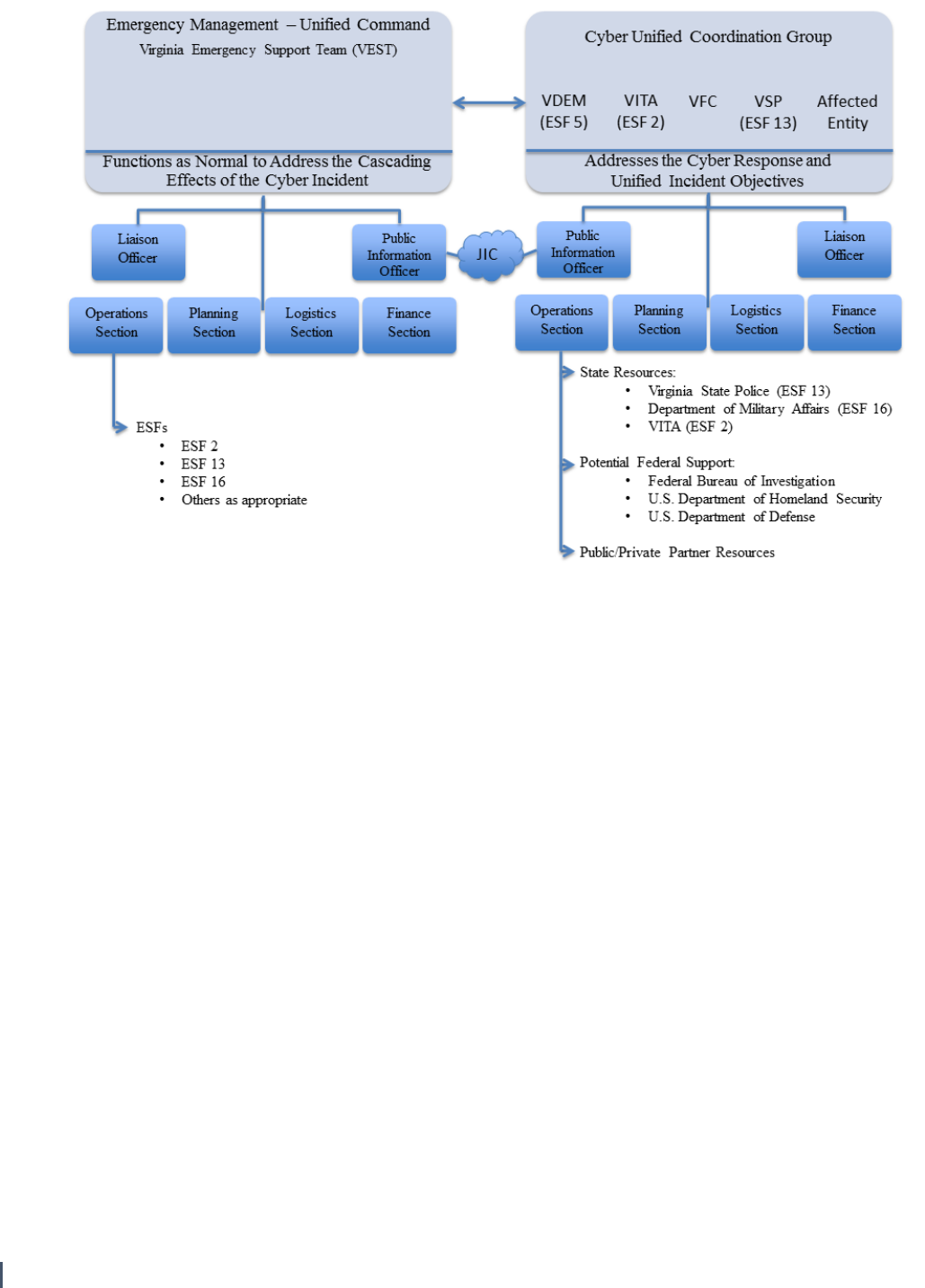

If the cyber incident is deemed an emergency or

impacts local or private critical infrastructure,

the incident is managed through a Unified

Command (UC) structure (see Figure 2 below),

which “is scalable and may be adjusted to

accommodate unique requirements or incident

complexity.”

56

An emergency is defined by law

as “any occurrence, or threat thereof, whether

natural or man-made, which results or may

result in substantial injury or harm to the

population or substantial damage to or loss of

property or natural resources.”

57

The UC structure is led by the VDEM Virginia

Emergency Support Team (VEST), which

“coordinates the response to and recovery from

the overall emergency and any cascading effects

of the incident” within the UC.

58

VDEM also

provides resources and emergency

management expertise for local and state

governments to prevent, prepare for, and

respond to incidents. The cyber-specific

response is led by a Cyber Unified Coordination

Group (Cyber-UCG), which aligns with the

overall emergency management VEST (see

Figure 2 below).

59

The Cyber-UCG is composed of five entities:

VITA, VDEM, VSP, VFC, and the affected entity.

Roles and responsibilities for cyber incident

response are broken down by agency. The VITA

CISO oversees the protection of Commonwealth

networks and lends its technical expertise to the

Cyber-UCG during response operations. VSP is

the lead agency for threat response, “overseeing

and coordinating” cyber criminal

investigations.

60

VDEM manages asset response,

or the coordination or resources to support

cyber incident response. The VFC coordinates

and disseminates non-sensitive/non-identifying

information to Cyber-UCG agencies, federal

agencies and/or private CI partners to ensure

the response is timely and effective.

The VFC also collects and analyzes law

enforcement information at the conclusion of an

incident.

61

Finally, a representative from the

affected entity, such as local government or a

private sector organization, provides

information regarding impacted systems. The

Cyber-UCG structure is scalable and applicable

to both small- and large-scale incidents.

16

Figure 2. Virginia Unified Command Structure (DRAFT)

(Taken from the 2017 Commonwealth of Virginia, Department of Emergency Management “Cyber Incident Response Plan”)

To manage an emergency response, local

government officials and private companies may

request state or federal assistance. To this end,

the Governor may call on the Secretary of Public

Safety and Homeland Security (PSHS) to provide

additional resources, such as expertise housed

within the Department of Military Affairs. PSHS

serves as the Governor’s Homeland Security

Advisor and oversees 11 agencies, including VSP

and the Department of Military Affairs, which

includes VANG.

62

VANG can leverage cyber-

trained personnel to help respond to an

emergency cyber incident.

63

In addition, the VSP

High-Tech Crimes (HTC) division may play a role

in cyber-crime incident response by providing

digital forensic analysis and investigative

services to local, state, and federal law

enforcement agencies.

The Commonwealth regularly assesses

emergency response activities, including cyber

incident response. The SCP, created by law in

2016, is an advisory body within PSHS and is

chaired by the Secretary of Public Safety and

Homeland Security. The 34-member SCP is

charged with assessing “the implementation of

statewide prevention, preparedness, response,

and recovery initiatives” and making

recommendations to the Governor to address

emergency preparedness.

64

Members include

representatives from the House and Senate,

executive branch, and local governments;

private citizens; the Attorney General; and the

Lt. Governor. The SCP submits annual reports to

the Governor outlining the Commonwealth’s

emergency preparedness efforts, including

cybersecurity.

17

V. Information Sharing

The Challenge:

How to engage across multiple public and private organizations to

share cybersecurity-related information?

Features of Virginia’s Governance Approach:

The VITA CSRM provides the bulk of information sharing about

operational issues to government departments and agencies.

The VITA CSIRT distributes cyber intelligence to Commonwealth

agencies and law enforcement.

The VFC shares information about cyber threats across state,

federal, and local governments.

To facilitate information sharing about a broad range of

cybersecurity topics with the private sector, the Commonwealth

established the VCSP.

The Commonwealth utilizes an array of governance mechanisms to share different types of

information across government, public, and private organizations (see Table 1 below for a summary of

various information sharing entities).

Table 1. Summary of Information Sharing Entities

Information

Sharing Entities

Type of Information Shared

Target Audience

VITA CSRM

Cybersecurity operational information

Departments and agencies

VITA CSIRT

Information security information

Agencies and state law enforcement

PSHS VFC

Cyber threat intelligence

State, local, and federal governments

VCSP

A broad range of cybersecurity

information

Private sector

To support information sharing at the

department and agency levels about a broad

range of cybersecurity operational issues, the

VITA CSRM conducts monthly Information

Security Officers Advisory Group (ISOAG)

meetings, which provide security training and

facilitate knowledge exchange. “In 2015, more

than 1,700 security professionals attended the

ISOAG meetings.”

65

The ISOAG meetings allow

ISOs to “talk about the issues that are facing

state agencies such as cloud security, lockdown

of computers, lockdown of servers, compliance,

latest security patches, and other day-to-day

topics that are of concern to ISOs,” said Lee

Tinsley, CIO of the Department of Veterans

Services.

66

In addition, the CSRM used the ISO

18

Security Council as a resource to assist in sharing

best practices between agencies.

The CSIRT, also part of VITA, distributes “cyber

intelligence information to both agencies and

law enforcement within the commonwealth.”

67

The CSIRT “develops relationships with state,

Federal, and local partners” and regularly

exchanges information about information

security issues with these entities.

68

The VFC also plays an important role by sharing

information about cyber threats across state,

federal, and local governments. Organized

under PSHS, the VFC collects, analyzes, and

shares “threat intelligence between the federal

government and state, local, and private sector

partners.”

69

The VFC is physically located within

VSP headquarters and collaborates regularly

with the HTC division and VITA. The close

proximity of the VFC with the VSP allows for

“quick, ready access to investigators,” which is a

unique feature of state fusion centers.

According to Rob Reese, manager of the Cyber

Intelligence Unit at the VFC, this close

collaboration improves the quality of threat

analysis and allows law enforcement and

prosecutors to work together more quickly at

the inception of a suspected cyber crime,

carefully collecting and inventorying evidence

required to build a successful case.

70

Although the VFC cyber capability is new,

established in late 2016 and fully staffed in the

first quarter of 2017, leaders plan to provide

additional resources in the coming years to

increase staff.

71

Today, the VFC is focused on

identifying cyber threats to the

Commonwealth’s network, private companies

doing business in the Commonwealth, localities,

and private citizens, and sharing that

information with VFC partners. As the VFC

capability grows over the next several years, the

focus will include “looking at the broader scope

of what the state enterprise is experiencing in

cyber-space,” analyzing that information, and

sharing it with public and private infrastructure

owner/operators, the VSP HTC division, and

VITA.

72

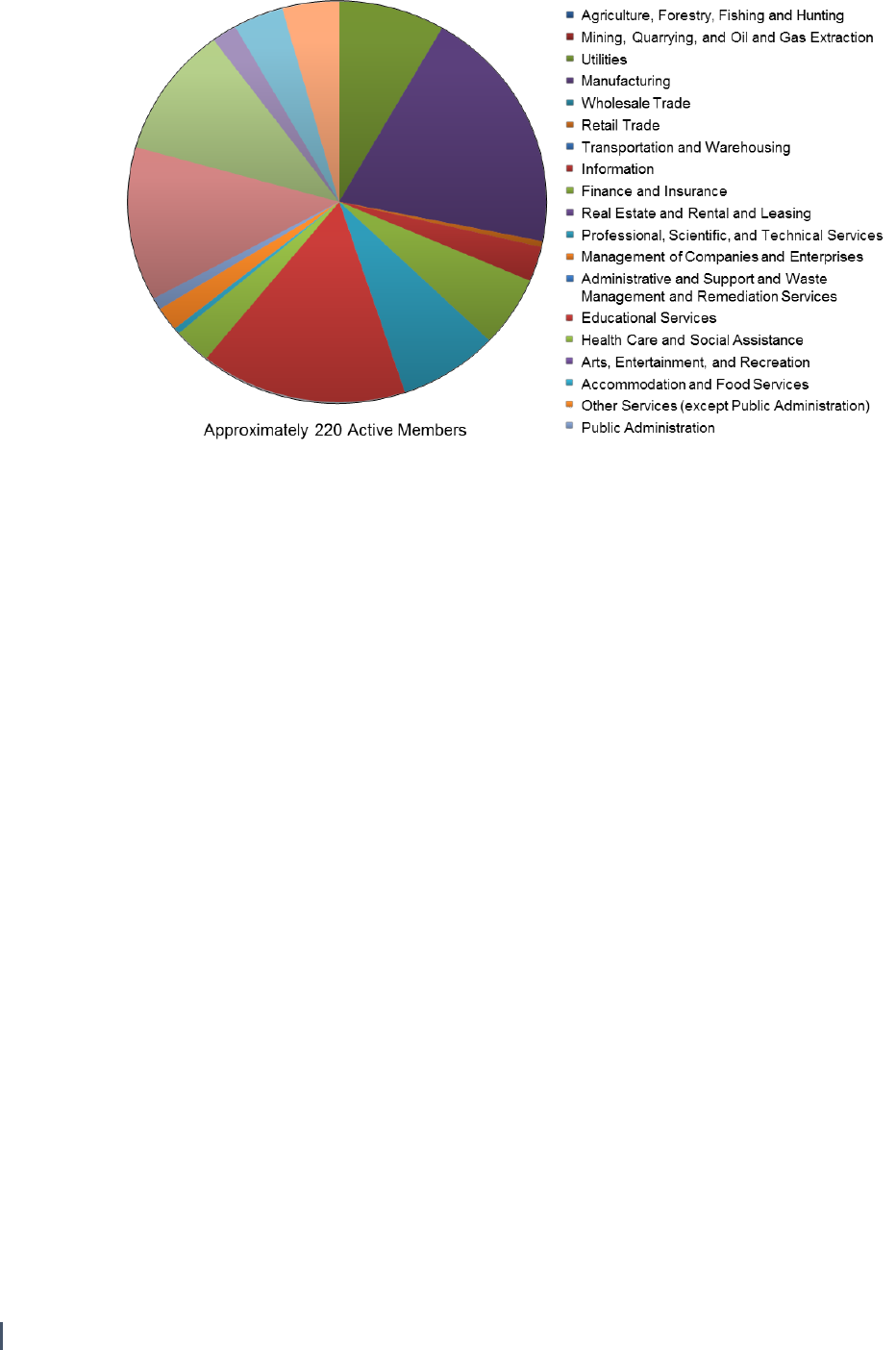

To facilitate information sharing about a broad

range of cybersecurity topics with the private

sector, the Richmond FBI – in partnership with

VITA and several private companies – formed

the VCSP. The VCSP is a partnership of

approximately 220 private sector entities (such

as major critical infrastructure owner/operators,

retailors, and healthcare providers), and the

public sector (see Figure 3 below for an overview

of membership). There are three VCSP

advisors/liaisons: the FBI, the VITA CISO, and a

representative from a large power company.

73

The VCSP gathers cyber professionals from

across industries in a trusted environment to

share information and lessons learned.

74

At the

five meetings held each year, VCSP members

collaborate to share threat intelligence and

discuss credential management issues and risks

associated with supply chain security.

19

Figure 3. VCSP Membership Representation as of April 2016

75

In addition, the Commonwealth is in the process

of expanding information sharing through an

Information Sharing and Analysis Organization

(ISAO).

76

In April 2015, the Governor signed an

executive order “establishing the Nation’s first

state-level Information Sharing and Analysis

Organization (ISAO).”

77

The ISAO is “intended to

enhance the voluntary sharing of critical

cybersecurity threat information in order to

confront and prevent potential cyberattacks.”

78

ISAOs are designed to “complement existing

structures and systems that are used to share

critical cybersecurity threat information across

levels of government and industry sectors.”

79

20

VI. Workforce &

Education

The Challenge:

How to work across multiple public and private organizations to

shape responses to cybersecurity workforce shortages and

education needs?

Features of Virginia’s Governance Approach:

The Commonwealth utilized several governance mechanisms

and developed programs to strengthen partnership between

government, higher education, and industry.

The Commonwealth collaborated with institutions of higher

education to create the Virginia Cyber Range, a virtual, cloud-

based environment to enhance cybersecurity education in

Virginia’s high schools, colleges, and universities.

Virginia’s community colleges and industry have collaborated to

instantiate apprenticeship and credentialing programs.

VITA has leveraged its role across government to provide

certification programs for existing state workers.

To address a talent gap in cyber-skilled workers,

the Commonwealth used several governance

mechanisms, and developed programs to

strengthen partnership between government,

higher education, and industry.

80

Many of these

efforts were the result of the Commission (see

Sections I and V), which made several

recommendations to improve the cyber

workforce.

To strengthen cybersecurity education, the

Commonwealth developed a partnership with

higher education institutions and created the

Virginia Cyber Range in 2016. The Cyber Range is

a virtual, cloud-based environment designed to

enhance cybersecurity education in Virginia’s

high schools, colleges, and universities.

81

It was

originally a recommendation put forth by the

Commission in 2015. The General Assembly

provided $4 million to support the Cyber Range

and directed Virginia Tech to “serve as the

coordinating entity.”

82

“The Virginia Cyber

Range is led by an executive committee

representing public institutions of higher

education that are nationally recognized centers

of academic excellence in cybersecurity within

the Commonwealth of Virginia.”

83

This education initiative includes teaching the

teachers as well as the students. The Cyber

Range offers two primary services: (1) a

courseware repository providing teachers from

high schools, colleges, and universities with

access to standardized lessons to download and

use in the classroom; and (2) access to the cloud

(through Amazon Web Services) to host

21

cybersecurity labs and exercises for students.

84

The courses expose students to cybersecurity

concepts, while the cloud-hosted lab

environment allows students to practice those

concepts in a hands-on environment. The goal is

to provide teachers with courses and lessons

contributed by any of the nine National Security

Agency (NSA)/DHS Cybersecurity Centers of

Academic Excellence (CAEs) in the

Commonwealth to improve the quality and

variety of cybersecurity education. Allowing

teachers to share materials developed by CAEs

reduces the amount of time and the associated

cost to develop coursework. While the Cyber

Range is currently only accessible to faculty

members at Virginia public high schools and

colleges, discussions are underway to determine

whether materials could be made available to

other states and interested parties on a fee

basis.

The Commonwealth used governance

mechanisms to promote collaboration between

industry and higher education to support

workforce development for new and existing

workers. For new workers, in 2016 the General

Assembly acted on a Commission

recommendation and passed the New Economy

Workforce Grant Program (NEWGP). The

NEWGP allocates $12 million over two years to

a variety of Virginia’s community colleges to

provide direct subsidies to students to cover a

portion of the cost of obtaining industry

credentials.

85

,

86

To implement this grant,

“Virginia’s Community Colleges consulted with

Virginia businesses to develop the list of eligible

credentials that can provide access to a wide

variety of high-demand jobs, such as…computer

network specialist…”

87

88

In addition, there is a

concerted effort to leverage the thousands of

military Veterans in the Commonwealth to

address cyber workforce shortages. For

example, in 2016 the Governor announced

“Cyber Vets Virginia,” an initiative designed to

provide Veterans with access to cybersecurity

training opportunities and resources to

encourage Veterans to enter the cyber

workforce.

89

Cyber Vets Virginia offers access to

free cyber training via private sector partners for

eligible Veterans living in Virginia and interested

in working in the cyber industry.

90

To increase cyber skills across its government

workforce, the Commonwealth leveraged the

role of VITA. VITA instituted a policy requiring

that all ISOs meet certification requirements and

receive training to understand Virginia’s

information security policies and procedures. To

help employees meet this requirement, the

Commonwealth now offers an ISO Certification

Program that is administered by the VITA CSRM.

Since instituting the policy in 2015, the VITA

CSRM has awarded 91 certifications, a 90

percent increase over 2013, before the policy

was implemented.

91

“ISO certification is an

important element of the commonwealth

information security program [because it]

demonstrates an understanding of information

security risks and commitment to promoting

information security in the commonwealth.”

92

Commission recommendations also led to a

series of laws intended to help bring younger

cyber-skilled employees into the state

workforce. Specifically, the General Assembly

passed a law establishing a scholarship program

that provides two-year scholarships to college

students who study cybersecurity in exchange

for a commitment of two years of public service

at a Virginia state agency.

93

22

VII. Deep Dive: Virginia

Cybersecurity

Commission

Introduction

The purpose of the “Deep Dive” is to provide a

more in-depth look at how the Commonwealth

applied a cross-sector solution to address a

specific cyber governance challenge.

The Challenge

Cybersecurity risks within a state are realized

across multiple public and private organizations.

Developing a comprehensive, cross-sector

approach to addressing these risks requires

mechanisms to incorporate these various

perspectives.

The Solution

In 2014, the Governor used executive order

authority to establish the Virginia Cybersecurity

Commission, a temporary body of experts from

across the executive and legislative branches of

government and the private sector. The

Commission developed cross-cutting

recommendations to strengthen cybersecurity

across the Commonwealth, many of which have

been implemented.

The Background

The Commission’s objective was to create a list

of actionable recommendations for the

Governor and the General Assembly to consider

to strengthen the Commonwealth’s

cybersecurity posture. Membership reflected

the Commonwealth’s understanding that

cybersecurity is an issue that requires both

public and private sector cooperation to

address. Co-chair and Secretary of Technology

Karen Jackson called the Commission and the

resulting list of recommendations a “game

changer” for those advocating for changes in law

to support cybersecurity-related investments,

describing it as a “grounding document” that

influenced decisions on budget, policy, and the

law.

94

The Commission was comprised of the

Secretaries of Technology, Commerce and

Trade, Public Safety, Education, Health and

Human Resources, Veterans Affairs, and

Homeland Security, and 11 citizens appointed by

the Governor. The latter represented private

industries such as a global credit card company,

a large law firm, and defense and aerospace

companies, among others.

95

Over two years, the Commission held nine

meetings, several Working Group sessions, and

nine Town Hall events to develop a set of

recommendations. “There were five

subcommittees, each focusing on a specific area

of interest to the Commission…: (1)

Infrastructure; (2) Education and Workforce; (3)

Public Awareness; (4) Economic Development;

and (5) Cyber Crime.”

96

The Commission was

charged to:

97

Identify high-risk cybersecurity issues

facing the Commonwealth,

23

Provide advice and recommendations

regarding how to secure state networks,

systems, and data,

Provide suggestions regarding how to

include cybersecurity into the

Commonwealth’s emergency

management and disaster response

capabilities,

Offer suggestions to promote cyber

awareness among citizens, businesses,

and government entities,

Recommend changes to training and

education programs (K-12 and beyond)

to build a pipeline of cybersecurity

professionals, and

Offer strategies to improve economic

development opportunities throughout

the Commonwealth.

The members broke into working groups to

study cybersecurity-related risks across the five

areas.

98

For example, the Cyber Crime Work

Group, which included Brian Moran, Secretary

of Public Safety and Homeland Security, and

Paul Tiao, private attorney and partner at

Hunton and Williams, LLP, “reviewed existing

statutes governing crimes in cyberspace” and

studied how to improve “coordination between

the private sector and law enforcement on

information sharing and prosecuting

cybercrimes.”

99

The Work Group reviewed

Virginia statutes, such as the Computer Crimes

Act and Data Breach Notification Act, with

assistance from:

Students from the George Washington

University Trachtenberg School of Public

Policy

Virginia Attorney General’s Office

VSP

Office of Public Safety and Homeland

Security

100

“As a result of the group’s research, the Work

Group proposed, introduced (and successfully

passed in the 2015 General Assembly session)

legislation to support law enforcement in its

fight against cybercrime…”

101

The Commission finalized its recommendations

and, after two years, concluded activities on

March 29, 2016. The Commission submitted a

set of 29 recommendations to the Governor for

consideration. Many of these recommendations

required executive department and/or agency

action, such as adoption of identity

management and encryption standards for all

Commonwealth departments and agencies.

Other recommendations required coordination

with and approval from the General Assembly.

For example, in 2015, the General Assembly

passed SB1307, which “clarifies language for

search warrants for seizure, examination of

computers, networks, and other electronic

devices.”

102

The Commission has seen many of

its recommendations implemented and

continues to influence executive and legislative

actions today.

24

VIII. Acronyms

Acronym

Definition

CAE

Cybersecurity Center of Academic Excellence

CIO

Chief Information Officer

CIRT

Computer Incident Response Team

CISO

Chief Information Security Officer

CRWG

Cyber Response Working Group

CS&C

Office of Cybersecurity and Communications

CSIRT

Commonwealth Security Incident Response Team

CSRM

Commonwealth Security and Risk Management

Cyber-UCG

Cyber Unified Coordination Group

DHS

Department of Homeland Security

FBI

Federal Bureau of Investigation

FFRDC

Federally Funded Research and Development Center

HSSEDI

Homeland Security Systems Engineering and Development Institute

HTC

High Tech Crimes

ISAO

Information Sharing and Analysis Organization

ISO

Information Security Officer

ISOAG

Information Security Officers Advisory Group

IT

Information Technology

ITAC

Information Technology Advisory Council

NASCIO

National Association of State Chief Information Officers

NEWGP

New Economy Workforce Grant Program

NSA

National Security Agency

PSHS

Public Safety and Homeland Security

SCP

Secure Commonwealth Panel

SLTT

State, Local, Tribal and Territorial

UC

Unified Command

VANG

Virginia National Guard

VCSP

Virginia Cyber Security Partnership

VDEM

Virginia Department of Emergency Management

VEST

Virginia Emergency Support Team

VFC

Virginia Fusion Center

VITA

Virginia Information Technology Agency

VSP

Virginia State Police

| 25

1

Statistical Atlas, “Overview of Virginia.” Data based on US Census Bureau 2010 census. Available:

http://statisticalatlas.com/state/Virginia/Overview. Retrieved August 2017.

2

Information regarding elected officials and state cybersecurity executives was validated in October 2017. "Fast Fact" details were

collected in August 2017.

3

Virginia.gov, “VITA Organization.” Available: https://www.vita.virginia.gov/about/.

4

For purposes of this case study, governance refers to the laws, policies, structures, and processes that enable people within and across

organizations to address challenges in a coordinated manner through activities such as prioritization, planning, and decision making.

5

In 2003, the legislature passed House Bill 1926 (Nixon) and Senate Bill 1247 (Stosch) to establish VITA.

6

Virginia Information Technologies Agency, “ITRM Policies, Standards & Guidelines.”

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/library/default.aspx?id=537#securityPSGs.

7

Office of the Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia, Executive Order 8, “LAUNCHING "CYBER VIRGINIA" AND THE VIRGINIA CYBER

SECURITY COMMISSION,” February 25, 2014, http://governor.virginia.gov/media/3036/eo-8-launching-cyber-virginia-and-the-virginia-

cyber-security-commissionada.pdf.

8

Commonwealth of Virginia, “Cyber Commission Final Report.” (2016, March 29). Available:

https://cyberva.virginia.gov/media/8139/cyber-commission-final-report.pdf.

9

“Virginia Cyber Security Partnership.” (2016, April). Available: https://1pdf.net/download/virginia-cyber-security-

partnership_591328a7f6065d001d719da3.

10

Virginia Final Cyber Security Report. (2016). Available: https://cyberva.virginia.gov/media/6424/virginiacybersecurity_printfinal-

83116.pdf.

11

Virginia Cyber Security Partnership,” (2016, April). Available: https://1pdf.net/download/virginia-cyber-security-

partnership_591328a7f6065d001d719da3.

12

The Virginia Cyber Range. Available: https://virginiacyberrange.org/.

13

Ibid. The nine colleges and universities designated as NSA/DHS Cybersecurity CAEs) or Department of Defense (DoD) Cyber Crime

Center (DC3) National Centers of Digital Forensics Academic Excellence (CDFAEs) are:

1. George Mason University – NSA/DHS CAE in Cyber Defense Education (CAE-CDE) and Research (CAE-R)

2. James Madison University – NSA/DHS CAE-CDE

3. Lord Fairfax Community College – NSA/DHS CAE -CDE 2-Year Education (CAE-CDE 2Y)

4. Longwood University – DC3 CDFAE

5. Norfolk State University – NSA/DHS CAE-CDE

6. Northern Virginia Community College – NSA/DHS CAE-CDE 2Y

7. Radford University – NSA/DHS CAE-CDE

8. Tidewater Community College – NSA/DHS CAE-CDE 2Y

9. Virginia Tech – NSA/DHS CAE-R, and CAE in Cyber Operations (CAE-O)

10. Danville Community College – NSA/DHS CAE-CDE 2Y

14

Department of Homeland Security Advisory Council, “Final Report of the Cybersecurity Subcommittee, Part II – State, Local, Tribal &

Territorial (SLTT).” (2016, June). Available:

https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/HSAC_Cybersecurity_SLTT_FINAL_Report.pdf.

15

About NASCIO. Available: https://www.nascio.org/AboutNASCIO.

16

“The Commonwealth strategic plan for information technology shall be updated annually and submitted to the Secretary for approval,”

§ 2.2-2007. Available: https://lis.virginia.gov/cgi-bin/legp604.exe?151+ful+CHAP0768.

17

Virginia code §2.2-225. Available: https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title2.2/chapter2/section2.2-225.

18

VITA, “CY 2017 Update to the Commonwealth Strategic Plan for Information Technology for 2017 – 2022.” Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/it-governance/cov-strategic-plan-for-it/itsp---2017-update/.

19

Ibid.

20

Ibid.

21

Ibid.

22

Va. Code Ann. §2.2-225 (1999).

23

Va. Code Ann. §2.2-2100 (1985).

24

Office of the Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia, Executive Order 8, “LAUNCHING "CYBER VIRGINIA" AND THE VIRGINIA CYBER

SECURITY COMMISSION,” February 25, 2014, http://governor.virginia.gov/media/3036/eo-8-launching-cyber-virginia-and-the-virginia-

cyber-security-commissionada.pdf.

25

Commonwealth of Virginia, “Cyber Commission Final Report.” (2016, March 29). Available:

https://cyberva.virginia.gov/media/8139/cyber-commission-final-report.pdf.

26

Interview with Secretary of Technology Karen Jackson (2017, March 24).

27

Ibid.

28

The law directs executive branch agencies to “obtain CIO approval prior to the initiation of any Commonwealth information technology

project or procurement [providing an] business case, outlining the business value of the investment, the proposed technology solution, if

known, and an explanation of how the project will support the agency strategic plan, the agency's secretariat's strategic plan, and the

| 26

Commonwealth strategic plan for information technology.” Virginia code §2.2-2018.1. Available:

https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title2.2/chapter20.1/section2.2-2018.1/ See also Virginia code §2.2-2007. Available:

https://law.lis.virginia.gov/vacode/title2.2/chapter20.1/section2.2-2007/.

29

D. Verton, “Look Who’s MeriTalking: Virginia CIO Nelson P. Moe.” MeriTalk.com (2016, May 2). Available:

https://www.meritalk.com/look-whos-meritalking-virginia-cio-nelson-p-moe/.

30

Interview with CISO Mike Watson (2017, March 25).

31

Ibid.

32

The CIO established a CSRM directorate within VITA to fulfill his information security duties under §2.2-2009. The CSRM is led by the

Commonwealth’s CISO.

33

VITA, 2015 Commonwealth of Virginia Information Security Report. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/uploadedpdfs/vitamainpublic/security/2015COVSecurityAnnualReport.pdf.

34

Ibid., pp. 3-4.

35

Virginia.gov, Governor McAuliffe Announces Virginia Adopts National Cybersecurity Framework. (2014, February 12). Available:

https://governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/newsarticle?articleId=3284. See also NIST Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure

Cybersecurity, Version 1.0, February 12, 2014, Available:

https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cyberframework/cybersecurity-framework-021214.pdf.

36

VITA, 2015 Commonwealth of Virginia Information Security Report, p. 16. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/uploadedpdfs/vitamainpublic/security/2015COVSecurityAnnualReport.pdf.

37

Va. Code Ann. §2.2- 2009.

38

VITA, 2015 Commonwealth of Virginia Information Security Report. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/uploadedpdfs/vitamainpublic/security/2015COVSecurityAnnualReport.pdf. Page 13

of the report lists evaluation criteria for each type of program.

39

Interview with Mike Watson (2017, March 25).

40

Interview with Lee Tinsley, CIO, Virginia Department of Veterans Services (2017, June 12).

41

Ibid.

42

Executive Directive 6, “Governor McAuliffe Signs Executive Directive to Strengthen Cybersecurity Protocol.” (2015, August 31).

Available: http://governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/newsarticle?articleId=12544.

43

Ibid.

44

The Secure Commonwealth Panel (SCP) is established as an advisory board within the meaning of § 2.2-2100, in the executive branch of

state government. The Panel consists of 36 members as follows: three members of the House of Delegates, one of whom shall be the

Chairman of the House Committee on Militia, Police and Public Safety, and two non-legislative citizens to be appointed by the Speaker of

the House of Delegates; three members of the Senate of Virginia, one of whom shall be the Chairman of the Senate Committee on

General Laws and Technology, and two non-legislative citizens to be appointed by the Senate Committee on Rules; the Lieutenant

Governor; the Attorney General; the Executive Secretary of the Supreme Court of Virginia; the Secretaries of Commerce and Trade,

Health and Human Resources, Technology, Transportation, Public Safety and Homeland Security, and Veterans and Defense Affairs; the

State Coordinator of Emergency Management; the Superintendent of State Police; the Adjutant General of the Virginia National Guard;

and the State Health Commissioner, or their designees; two local first responders; two local government representatives; two physicians

with knowledge of public health; five members from the business or industry sector; and two citizens from the Commonwealth at large.

Except for appointments made by the Speaker of the House of Delegates and the Senate Committee on Rules, all appointments shall be

made by the Governor.

45

Interview with Isaac Janak, Cyber Security Program Manager, Office of Secretary of Public Safety and Homeland Security (2017, June

12).

46

K. Bortle and A. Burge, Cyber Security Incident Response, VITA. (2016, April 7).

47

K. Bortle and A. Burge, “Guidance on Reporting Information Technology Security Incidents,” VITA Commonwealth Security & Risk

Management Incident Response Team. (2016, April 7). Available: https://www.vita.virginia.gov/security/default.aspx?id=317.

48

VITA, IT Incident Response Policy. (2014, July 1). Available: https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/it-

governance/psgs/sec501-pampp-templates/doc/VITA-CSRM-IT-Incident-Response-Policy-v1_0.docx.

49

Ibid.

50

Va. Code Ann. §2.2-603(G).

51

VITA Guidance on Reporting Information Technology Security Incidents. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/security/default.aspx?id=317.

52

Ibid.

53

VITA Information Security Incident Reporting Form. Available:

https://vita2.virginia.gov/security/incident/secureCompIncidentForm/threatReporting.cfm.

54

VITA, 2015 Commonwealth of Virginia Information Security Report, p. 7. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/uploadedpdfs/vitamainpublic/security/2015COVSecurityAnnualReport.pdf. “All

executive branch agencies including institutions of higher education are required to report information security incidents to VITA except

for the University of Virginia (UVA), Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (VPI), and the College of William and Mary.” See

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/security/default.aspx?id=317.

55

VITA, “CSRM Information Security Incident Response Procedure v6_0,” revised 2/3/2014. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/resources/presentations/pdf/InformationSecurityIncidentResponseProcedure.pdf.

| 27

56

Virginia Department of Emergency Management, “Draft Cyber Incident Response Plan.” (2017, May), p. 2.

57

Va. Code Ann. §44-146.16.

58

Virginia Department of Emergency Management, “Draft Cyber Incident Response Plan.” (2017, May), p. 2.

59

The UC structure includes reference to emergency support functions (ESFs). According to DHS Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA), “ESFs provide the structure for coordinating Federal interagency support for a Federal response to an incident. They are

mechanisms for grouping functions most frequently used to provide Federal support to States…” See DHS, FEMA Emergency Support

Function Annexes. Available: https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/25512.

60

Virginia Department of Emergency Management, “Draft Cyber Incident Response Plan.” (2017, May), p. 2.

61

Ibid, p. 4.

62

Virginia Public Safety and Homeland Security, Cybersecurity, https://pshs.virginia.gov/homeland-security/cyber-security/.

63

Ibid. Since 2011, the VANG has participated in National Level Cyber Exercises such as the US Cyber Command's Cyber Guard (focus on

protection of critical infrastructure), DoD's Cyber Flag (focused on federal cyber National Mission Forces), and the National Guard's

annual Cyber Shield exercise (focused on defense of military networks).

64

Va. Code Ann. §2.2-222.3.

65

VITA, 2015 Commonwealth of Virginia Information Security Report, p. 4. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/uploadedpdfs/vitamainpublic/security/2015COVSecurityAnnualReport.pdf.

66

Interview with Lee Tinsley, CIO, Virginia Department of Veterans Services (2017, June 12).

67

VITA, 2015 Commonwealth of Virginia Information Security Report, p. 7. Available:

https://www.vita.virginia.gov/media/vitavirginiagov/uploadedpdfs/vitamainpublic/security/2015COVSecurityAnnualReport.pdf.

68

Ibid.

69

Virginia Public Safety and Homeland Security, Cybersecurity, https://pshs.virginia.gov/homeland-security/cyber-security/.

70

Interview with Rob Reese, Lead Analyst, Virginia Fusion Center (2017, June 28).

71

Interview with Captain Kevin M. Hood, Division Commander, Criminal Intelligence Division, Virginia State Police (2017, June 28).

72

Interview with Isaac Janak, Cyber Security Program Manager, Office of Secretary of Public Safety and Homeland Security (2017, June

12).

73

Virginia Cyber Security Partnership (2016, April). Available: https://1pdf.net/download/virginia-cyber-security-

partnership_591328a7f6065d001d719da3.

74

Virginia Final Cyber Security Report, 2016. Available: https://cyberva.virginia.gov/media/6424/virginiacybersecurity_printfinal-

83116.pdf.

75

Virginia Cyber Security Partnership (2016, April), p. 3. Available: https://1pdf.net/download/virginia-cyber-security-

partnership_591328a7f6065d001d719da3.

76

Ibid, p. 7.

77

Virginia.gov, Governor McAuliffe Announces State Action to Protect Against Cybersecurity Threats (2015, April 20). Available:

https://governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/newsarticle?articleId=8210.

78

ReedSmith, Technology Law Dispatch. Available: https://www.technologylawdispatch.com/2015/04/data-cyber-security/virginia-

launches-first-statelevel-information-sharing-and-analysis-organization/.

79

Virginia.gov, Governor McAuliffe Announces State Action to Protect Against Cybersecurity Threats (2015, April 20). Available:

https://governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/newsarticle?articleId=8210.

80

As of January 2017, according to Governor McAuliffe, “36,000 cyber jobs are open in the Commonwealth” and cannot be filled due to a