GLEBE ISLAND & WHITE BAY

PORT NOISE POLICY

December 2020

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page ii

Contents

1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1

1.1 Why this policy is needed .............................................................................................................. 1

1.2 Benefits ......................................................................................................................................... 1

1.3 Policy objectives ............................................................................................................................ 2

1.4 Key policy commitments ............................................................................................................... 2

1.5 Policy statement ............................................................................................................................ 3

2 Policy scope ................................................................................................................ 4

3 Legislative context ....................................................................................................... 6

3.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 6

3.2 NSW planning controls .................................................................................................................. 6

3.3 NSW environmental legislation for noise emission ....................................................................... 7

3.4 Port Noise Policy ........................................................................................................................... 8

4 Policy overview ............................................................................................................ 9

4.1 Policy development ....................................................................................................................... 9

4.2 Policy commencement and review ............................................................................................. 10

5 Policy application ....................................................................................................... 11

6 Noise guidelines ........................................................................................................ 13

6.1 Vessel Noise Guideline ............................................................................................................... 13

6.2 Landside Precinct Noise Guideline ............................................................................................. 14

6.3 Planning controls ......................................................................................................................... 15

7 Noise trigger levels and criteria ................................................................................. 16

8 Management and mitigation of port noise.................................................................. 18

8.1 Noise monitoring ......................................................................................................................... 18

8.2 Vessel noise reduction ................................................................................................................ 19

8.3 Landside noise mitigation ............................................................................................................ 19

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page iii

8.4 Whole of port noise mitigation ..................................................................................................... 19

Appendix A ........................................................................................................................ 24

History of Glebe Island and White Bay .............................................................................. 24

A.1. History of Glebe Island and White Bay ...................................................................... 25

Appendix B ........................................................................................................................ 30

Australian and international port noise criteria ................................................................... 30

B.1. Overview of other Australian and international port noise criteria .............................. 31

Appendix C ........................................................................................................................ 35

Changes in noise levels at Glebe Island and White Bay .................................................... 35

C.1. Changes in port noise ............................................................................................... 36

C.2. Background noise levels............................................................................................ 37

Influence of the port and wind on background noise levels .................................................................. 38

Appendix D ........................................................................................................................ 39

Comparison with criteria for other vehicles ........................................................................ 39

D.1. Overview ................................................................................................................... 40

D.2. Aircraft ....................................................................................................................... 41

Individual aircraft ................................................................................................................................... 41

Airport infrastructure and surrounding development ............................................................................. 41

D.3. Road .......................................................................................................................... 43

Individual vehicles ................................................................................................................................. 43

Road infrastructure ................................................................................................................................ 43

Noise Abatement Program .................................................................................................................... 45

Encroaching development ..................................................................................................................... 45

D.4. Rail noise ................................................................................................................... 46

Individual locomotives and wagons ....................................................................................................... 46

Freight Noise Attenuation Program ....................................................................................................... 46

Rail infrastructure .................................................................................................................................. 47

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page iv

D.5. Vehicles operating within an industrial premise ......................................................... 48

D.6. Encroaching development ......................................................................................... 49

Appendix E ........................................................................................................................ 50

Factors influencing vessel noise ........................................................................................ 50

E1. Sources of air-borne noise ........................................................................................ 51

E2. Measurement ............................................................................................................ 51

Descriptors ............................................................................................................................................ 51

Directivity ............................................................................................................................................... 52

Frequency content ................................................................................................................................. 52

Modulation ............................................................................................................................................. 53

Factors that may influence measurements ........................................................................................... 53

Glossary ................................................................................................................................ i

See separate documents available on website for:

Appendix F - Vessel Noise Guideline

Appendix G - Landside Noise Guideline

Appendix H - Noise Standard

Appendix I - Noise Maps

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 1

1 Introduction

1.1 Why this policy is needed

The ports in New South Wales (NSW) are critical pieces of infrastructure essential for the transportation of

goods and passengers. The port of Glebe Island and White Bay is a transportation hub that:

• enables efficient delivery of bulk construction materials

• accommodates the second cruise terminal in Sydney Harbour

To meet expected future demand for bulk construction materials in NSW, there is a need for new port

developments and an increase in shipping numbers at Glebe Island and White Bay. Unless properly

managed, this has the potential to increase noise levels and community exposure to noise over time. To

improve noise management there is a need to transition noise management to a consistent approach that is

simpler and fairer.

Individual port users currently monitor and evaluate noise under different environmental requirements and

planning approvals. This leads to inconsistent reporting, noise limits and regulation between operators,

inconsistency and uncertainty in the planning approval process for new port infrastructure, and a lack of

clarity for local residents and the community.

Port Authority of New South Wales (Port Authority) has considered previous community feedback about port

noise and has consulted with the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) to develop this new Port Noise

Policy. Given the location of the port to surrounding residential development some impacts will be inevitable.

The purpose of this policy is to reduce impacts to the greatest extent practicable whilst allowing the ongoing

operation of the port facility. The intention of the policy is to provide a process for proactive management of

port-related noise by Port Authority using contractual means, together with guidelines for consistent

assessment and management, which may be used to inform planning and approvals for port activities.

Port Authority is committed to proactively managing port noise in a way that is acceptable to residents and

the local community while recognising Glebe Island and White Bay’s ongoing, long-term status as a working

port.

1.2 Benefits

By implementing this policy, Port Authority aims to achieve the following benefits for residents and

stakeholders:

• improved and consistent management of noise from the port

• certainty for residents, industry, regulators and approval authorities about anticipated and acceptable

levels of noise collectively from vessel and landside port activities

• establishment of a long term commitment to reduce vessel noise and community exposure

• enhanced communication about typical port noise emissions to the community and stakeholder through

the production of noise maps.

This policy is the first of its kind in Australia. It sets noise triggers for an individual vessel in the context of

overall community exposure to noise from Glebe Island and White Bay. There are currently no international

or national design criteria that control noise emissions from a vessel to limit impacts on the community.

Before this policy, the only noise criteria specific to vessels have been international requirements for on-

board safety and crew comfort.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 2

1.3 Policy objectives

Through changing context and interpretation, port noise management and requirements have become

inconsistent for both landside activities and vessels, with different operators within the port being required to

meet different goals. Activities and noise at the port has also changed over time.

Since the existing industrial noise guidelines were introduced, noise assessments were carried out on an

individual development basis for each port activity without considering the port’s overall noise emissions.

While the guidelines did have a cumulative assessment approach, it was not well suited to an active and

dynamic port environment where vessel berthing activities resulted in transient background noise levels and

impacts. Noise assessments have also contained inconsistencies as to whether vessel noise has been

included or excluded as a source of industrial noise.

Compliance with noise limits set under the existing guidelines has generally been problematic given they use

industrial noise criteria that were not specifically based on vessel noise, and that the original planning and

construction of White Bay and Glebe Island port area predates the guidelines.

In light of the above, the Port Noise Policy aims for a best practice approach to port noise management. The

policy’s objectives are to:

• manage port noise as a whole precinct rather than as individual operators

• define and clarify a consistent approach to port noise management that has appropriate mechanisms to

facilitate long term noise reduction of vessels

• improve and simplify management of landside port noise

• concisely communicate overall port noise managed under this policy through the use of noise mapping.

1.4 Key policy commitments

The Port Noise Policy, along with its guidelines, procedures and operating protocols, aims to achieve the

above objectives through the following overarching commitments:

• proactive management of noise emissions from the port, by Port Authority and its tenants

• requirements for each individual ship visiting the berths of Glebe Island and White Bay to meet noise

limits, and agreed consequences if these limits are exceeded

• fair and reasonable allocation of industrial noise criteria for landside activities, with consequences if the

precinct criteria are exceeded

• certainty for the community, industry, regulators and approval authorities about the level of noise from

collective port activities

• noise mapping of port activities to guide future noise assessments and planning controls for proposed

new developments encroaching on the port in the areas surrounding Glebe Island and White Bay

• goals for long term noise reduction of vessel noise while recognising the continued long-term role of

Glebe Island and White Bay as a transportation hub.

The Port Noise Policy’s operating protocols, guidelines and procedures will be implemented to assist Port

Authority in meeting these commitments. If their application may lead to an outcome in specific situations

where commitments may not be achieved, Port Authority commits to always striving to achieve the policy

objectives. This includes the use of other options to meet these overarching commitments, such as

proposing amendments to operating protocols and the policy’s guidelines and procedures.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 3

1.5 Policy statement

Port Authority is committed to managing impacts from the port effectively and sustainably. To achieve this

commitment, Port Authority has developed this port specific noise policy which collectively assesses and

manages noise from:

• landside activities as a whole across the port on a precinct basis

• vessels on an individual and per berth basis.

By developing this Port Noise Policy, Port Authority intends to better manage noise emissions in a strategic

way that provides more certainty to residents and the broader local community while also maximising the

utilisation of the port within these noise limits. Ongoing utilisation is supported by Sydney Regional

Environmental Plan (SREP) No 26 – City West which recognises the need for ongoing 24-hour port

operations and that these operations may generate noise and traffic movement.

Port Authority’s corporate commitments and principles for managing noise from the activities at Glebe Island

and White Bay are outlined in our operating protocols, developed under our guidelines and procedures (see

Table 1 in Section 4 of this policy for further detail).

These documents ensure that these port activities meet the requirements of the Protection of the

Environment Operations (POEO) Act 1997 and the Environmental Planning and Assessment (EP&A) Act

1979, both aimed at protecting community amenity while allowing for critical port development.

There are three ways in which Port Authority influences port noise:

• development and operation of Port Authority’s landside port infrastructure

• monitoring of its tenants’ development and operation of port infrastructure

• management of noise from vessels berthed at Glebe Island or White Bay.

Effective management of port noise requires the combined effort of Port Authority, its tenants, regulatory and

planning authorities and the vessel operators.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 4

2 Policy scope

This Port Noise Policy aims to address port noise originating from port activities at Glebe Island and White

Bay.

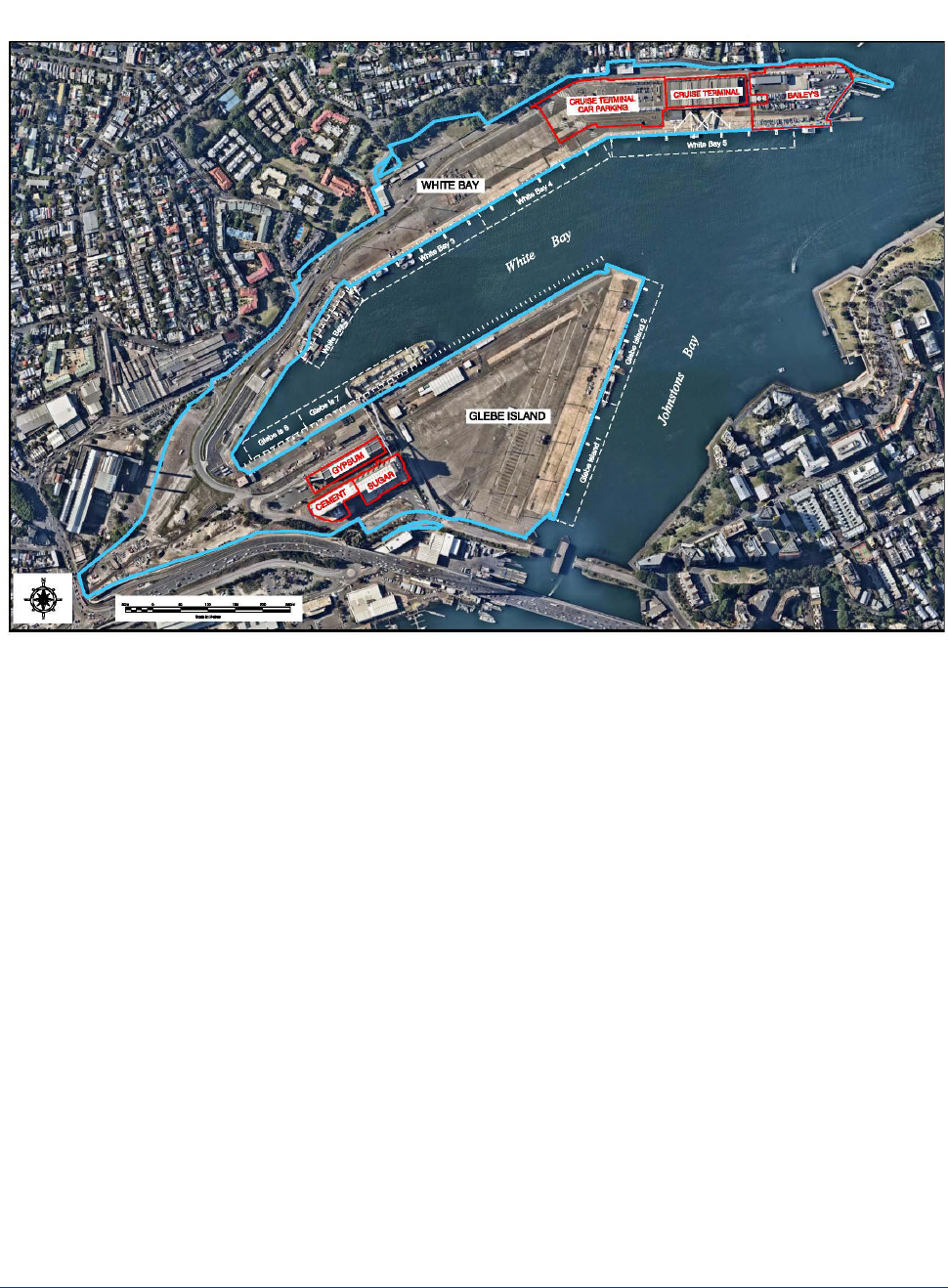

Figure 1: Spatial boundary of Glebe Island and White Bay, showing berth locations and key port uses

Source: Nearmap (October 2019)

Noise from port activities can fall within two broad categories:

• landside activities, typically including noise from the processing of cargo and warehousing operations

• vessels at berth, typically including noise from on-board generators, fans and cargo unloading systems

(self-extraction using on-board equipment).

Environmental criteria for noise are generally applied to developments on port land through planning and

environmental approvals. Any noise mitigation that is required is generally applied to noise at its origin and

generally relates to achieving external noise levels.

This Port Noise Policy aims to set the environmental criteria for:

• existing tenants’ future activities

• new port developments and operations

• vessels utilising the existing berths (existing tenants’ operations) at Glebe Island and White Bay.

The environmental criteria specified in this policy are recommended by Port Authority to be incorporated by

approval authorities in planning approvals and environmental protection licences.

In addition, this policy identifies port noise levels and criteria which may be used as guidance in setting

planning controls for new encroaching developments (commercial and residential) being constructed in

areas near to the port. These planning controls could take effect if included in a statutory planning policy or

requirements such as a State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP) or development consent. These

controls will not include mitigation of noise at its origin as this is already being applied through this Port Noise

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 5

Policy and other mechanisms. These planning controls may introduce criteria related to internal noise levels

for these developments and focus on building design to reduce noise intrusion and land use conflicts. If

adopted, this approach would be consistent with existing provisions in the State Environmental Planning

Policy (Infrastructure) 2007 (ISEPP) for developments proposed near busy roads and rail lines.

The Port Noise Policy is most relevant to the following stakeholders:

• Port Authority

• community

• port users (tenants and vessel operators)

• developers of commercial and residential land surrounding the port

• acoustical consultants

• regulators and approval authorities.

The associated guidelines, procedures and operating protocols are targeted to be used by Port Authority,

port users and developers.

This Port Noise Policy seeks to manage the noise from port operations. Construction activities carried out at

Glebe Island and White Bay, including the noise associated with the use of barges, are not subject to this

policy where they are governed by an existing and comprehensive construction noise assessment and

approval framework. This is to avoid duplication and the creation of inconsistency in noise management of

construction activities in the port.

The management of noise from cruise ships and the passenger activities at the White Bay Cruise Terminal

and White Bay berth 4 is governed by the Port Authority’s Noise Mitigation Strategy which predates this

policy. While the White Bay Cruise Terminal Noise Mitigation Strategy was implemented before the

development of this policy, it is generally consistent with the commitments in this policy.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 6

3 Legislative context

3.1 Overview

The port of Glebe Island and White Bay is established long term infrastructure. Any environmental noise,

even from long established infrastructure, has the potential to cause annoyance and health impacts.

Where existing and planned noise levels from infrastructure is high, and greater residential amenity is

required at existing and new residences, planning controls have been developed to address potential for

impacts. These planning controls are developed and define acceptable noise levels within modified existing

dwellings and new dwellings.

Further, all changes to port activity must manage noise impacts having regard to the residences adjacent to

the port.

3.2 NSW planning controls

The EP&A Act sets out the laws under which planning in NSW takes place. Under Part 3 of the EP&A Act,

environmental planning instruments are made to guide and control development and land use.

Environmental planning instruments, which include SEPPs and Local Environmental Plans (LEPs), can

specify planning controls for certain areas and/or types of development. Development Control Plans (DCPs)

provide detailed planning and design guidelines to support the planning controls in the LEPs developed by

councils.

The requirement for residences to be designed to meet internal noise goals is common under these various

planning controls. It is particularly common for higher density dwellings, such as multi-storey buildings, which

are frequently constructed near industry, busy roads and railway and mass transit lines.

3.2.1 Planning controls for Bays West

Of direct relevance to this policy is SREP-26, which is the relevant environmental planning instrument for the

land identified as ‘City West’, including the Bays Precinct. The current version, dated February 2020 was

originally gazetted in 1992 and deemed as a SEPP from July 2009.

The aims of SREP-26 are to:

• establish planning principles of regional significance for City West, as a whole, with which development

in City West should be consistent;

• establish planning principles and development controls of regional significance for development in each

Precinct created within City West by this plan and by subsequent amendment of this plan, and

• promote the orderly and economic use and development of land within City West.

This environmental planning instrument identifies port functions as a key planning principle for the area,

stating that the operation, concentration and rationalisation of commercial shipping facilities is to be

supported to meet the changing needs of Sydney Harbour as a commercial port. In regards to the Bays

Precinct, SREP-26 sets out a number of planning principles including that development should recognise

that the port operates 24 hours a day and that the generation of noise, lighting and traffic movements are

necessarily associated with its operation.

Consistent with SREP-26 (SEPP), the following controls, some of which were historically developed, include

specific components to address noise from external sources such as roads and the port:

• Glebe Island and White Bay Masterplan 2000

• Leichhardt DCP 2000 (superseded), which was applied up to the time of being superseded by

Leichhardt DCP 2013

• Urban Development Plan (UDP) for Ultimo-Pyrmont Precinct (1995 and 1999 updates) (superseded but

applied at the time of development)

• Lend Lease Master Plan 1997 (Jackson’s Landing) (superseded but applied at the time of

development)

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 7

• Sydney DCP 2012

• specific development consents for Pyrmont requiring buildings to be designed so that noise from the

port and ANZAC Bridge do not result in internal noise levels exceeding those consistent with Australian

Standard 2107 - Recommended design sound levels and reverberation times for building interiors.

The Glebe Island and White Bay Masterplan identifies 24/7 port noise levels at residential receiver locations

ranging between 53dBA and 57dBA L

Aeq

. Subsequent work completed in accordance with the Lend Lease

Masterplan identified 24/7 noise levels up to 64dBA L

Aeq

at residences at Jackson’s Landing. The former

Urban Development Plan (UDP) for Ultimo-Pyrmont Precinct, adopted by the Minister of Urban Affairs and

Planning in 1995 and 1999 included noise attenuation requirements for development near major noise

sources such as the port facility and elevated arterial roads.

In summary, many of the above DCPs, Plans and development consents require buildings around the port to

be designed so that external noise levels from roads and industry (including the Port) do not produce internal

noise levels greater than Australian Standard 2107.

An example of a development consent condition for Jackson’s Landing where external noise levels were

assessed as being up to 64dBA L

Aeq

is outlined below:

The Development shall address the noise impacts from traffic and operations of the port. Prior to

lodgement of the Building Application a report shall be submitted to City West Planning indicating

compliance with the noise attenuation measures required to satisfy the criteria indicated in the Lend

Lease Master Plan 1997. This criteria being: (a) That the building will be acoustically treated, such

that the mean logarithmic L

Aeq

(1h) level will not exceed 35 dB(A) in sleeping areas at night time and

40 dB(A) in other internal areas (not including garages, kitchens, bathrooms and hallways) during

day time (night time meaning between 10pm and 6am on the following day)

3.2.2 Other examples of noise treated residences under a SEPP or planning controls

The use of planning controls for new residential developments to protect against existing noise from

infrastructure, industry and transport noise is common. Some examples include:

• all residential development in NSW near busy roads and rail corridors which is completed in

accordance with SEPP (Infrastructure) 2007

• Waterside, Penrith by Stockton

• residents near all major airports in Australia. This includes those with 24/7 operation and with curfews.

3.3 NSW environmental legislation for noise emission

The POEO Act and the POEO (Noise Control) Regulation 2017 (Noise Control Regulation) provide the main

legal framework and basis for managing noise in NSW. It also makes certain agencies the appropriate

regulatory authority (ARA) responsible for various premises/activities. This includes local councils, the EPA,

Marine Parks Authority, Roads and Maritime Services (now Transport for NSW).

3.3.1 NSW environmental noise policy

The EPA’s Noise Policy for Industry (NPfI) was designed to ensure that potential noise impacts associated

with industrial projects are managed effectively. This policy sets out the requirements for the assessment

and management of noise from industry in NSW. It aims to ensure that noise is kept to acceptable levels in

balance with the social and economic value of industry in NSW.

When new industry is being proposed or existing industry is being upgraded, redeveloped or needs review,

attention needs to be paid to controlling noise. The NPfI is designed to assist industry and

approval/regulatory authorities ensure that potential noise impacts associated with industrial projects are

managed effectively.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 8

3.3.2 NSW Environment Protection Licences (EPL) under the POEO Act

Under the POEO Act, an Environment Protection Licence (EPL) may be required for port activities,

depending on the nature of the activities. Currently, some EPLs in Glebe Island and White Bay have noise

limits and some do not. Hence different premises in the port have different noise requirements and limits.

3.4 Port Noise Policy

This policy is designed to facilitate improved noise outcomes and port operations within the context and

constraints of SREP-26, other planning controls and environmental legislation.

It aims ensure that noise from all vessels is managed in a consistent, transparent and fair manner,

regardless of vessel and cargo type. This policy thereby aims to address inconsistencies in approvals and

EPLs by ensuring that all vessels visiting the port of Glebe Island and White Bay are required to meet the

same noise standard.

This policy is an application of the NPfI (further information is included in Sections 6.2 and 8.4.1). As such

all new and upgraded operations need to be assessed to identify potential noise impacts and feasible and

reasonable mitigation applied.

The NPfI and superseded Industrial Noise Policy acknowledges:

• there are challenges for sites that predate the current noise policy to meet the latest noise criteria

• where it is not possible to meet the latest noise criteria, to instead consider the use of alternative noise

triggers that are practical to achieve with feasible and reasonable mitigation and within constraints

associated with the site. The alternative triggers are implemented with a noise reduction strategy to

reduce noise emissions towards the EPA policy criteria over a period of time.

In accordance with the NPfI, this policy identifies a practical mechanism to reduce port noise within the

context of planning controls for Bays West.

The noise maps produced under this policy and associated tables (Appendix I) also provide historical,

current and future information to improve transparency about noise, inform community and assist in the

application of planning controls.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 9

4 Policy overview

This policy is structured so that the main text provides an overview of how noise is managed including key

outcomes. How the outcomes are derived and applied are detailed in the associated guidelines, protocols,

standards and noise maps.

Table 1: Port Noise Policy components for Glebe Island and White Bay

Document

Purpose

Key points

Port Noise Policy

(this document)

Outlines overarching principles relating to

noise from vessels and, for landside activities,

managing a noise precinct. This includes the

context for noise assessments for new port

users and surrounding residential and

commercial development.

Outlines why the policy was developed.

Provides a summary of noise criteria for

vessels and landside activities by following the

appendices.

Summary of how port noise will be managed.

Vessel Noise

Guideline

(Appendix F)

Outlines the approach to assessing and

managing noise from vessels, including

preparing noise maps of current and projected

future noise levels.

Describes the process to set target noise

levels for vessels and the steps for completing

a vessel noise assessment.

Landside

Precinct Noise

Guideline

(Appendix G)

Details the process of assessing noise from

landside activities, setting user contribution

criteria, monitoring compliance and identifying

noise mitigation actions.

Shows how to set noise criteria for landside

activities and how to complete a landside noise

assessment.

Vessel Noise

Operating

Protocol

(published

online)

Details operating protocols applicable to each

berth to manage vessels which exceed

prescribed noise levels and includes specific

actions to manage exceedances.

Defines the steps to be taken if a vessel is

noisier than the trigger level.

Noise Standard

(Appendix H)

Documents the allocation of contributions by

individual port users to the whole-of-precinct

noise criteria for landside activities, and

defines the trigger noise level for vessels at

berth.

Lists the vessel trigger levels and landside

criteria for every berth and operator at the port.

Noise Maps

(Appendix I)

Graphically outlines the port noise emission

profile of Glebe Island and White Bay for

landside and vessel noise and may be used to

inform land use planning for new

developments encroaching on the port and

illustrate the expected noise environment

surrounding the port.

Contains noise maps for all noise from the

port. The vessel noise maps compare how

annual noise levels vary around the port and

over different years. The tables show the noise

levels from each ship while it is at the berth.

Additional maps show noise levels from

landside activities and total worst-case noise

levels for ships plus landside noise.

4.1 Policy development

The following factors and documents were considered in developing this policy and the development of

assessment criteria/trigger noise levels:

• planning and construction of White Bay and Glebe Island berths and other port infrastructure pre-dates

any environmental noise legislation and guidelines

• the close proximity of the port to residential areas

• differences between the way that ports and industrial sites operate

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 10

• assessment criteria for other forms of transport (road, rail and aircraft)

• EPLs for each of the premises for shipping in bulk licensed by the EPA in Glebe Island and White Bay

• any existing noise limits and restrictions to port operations as defined in planning approvals (noting that

consents for several premises within Glebe Island and White Bay do not have any restrictions on noise

or hours of operation).

• EPA Noise Policy for Industry 2017

• NSW State Environmental Planning Policy (Infrastructure) 2007

• Sydney Regional Environmental Plan - 26 – City West

• New Zealand Standard 6809:1999, Acoustics – Port Noise Management and Land Use Planning

The application of existing NSW noise policy to a port holds some unique challenges as there are significant

differences between a port and a typical industrial site, which are described in Table 2 below. It is primarily

for these reasons that this policy has been developed.

Table 2: Port operations versus industrial operations

Port site

Industrial site

Ports are a unique piece of infrastructure that

cannot be easily relocated.

An industrial site (or precinct) may be shifted over time to

an alternative location to reflect changes in surrounding

land use.

Vessels are transient and operate in a national

or international context.

An industrial site comprises mostly fixed mechanical plant

and equipment where there is a high degree of control over

the equipment and opportunities to invest in noise

reduction.

Noise emissions from individual operations may

be sporadic and/or seasonal.

Noise emissions from industrial operations are typically

relatively steady throughout the year.

Ports may act as a natural amphitheatre which

limits the effect of shielding.

Industrial sites are mainly fixed infrastructure where the site

and receivers share relatively level and similar topography.

Local regulation of noise emissions must be

reasonably congruent with international

standards.

Local regulation of noise emissions is largely independent

of international standards.

Further detail on various factors considered in the development of this policy including historical context and

changes in the port noise environment, other port and transport criteria, and factors influencing vessel noise

are included in the following appendices:

• history of Glebe Island and White Bay (Appendix A)

• overview of other Australian and international port noise criteria (Appendix B)

• changes in noise levels at Glebe Island and White Bay (Appendix C)

• comparison with approaches for other vehicles (Appendix D)

• factors influencing vessel noise (Appendix E).

4.2 Policy commencement and review

This policy will commence from January 2021. Information about the implementation of the policy to existing

and future port operations will be made available on the Port Authority’s website over time.

Port Authority will review this policy every five years, in consultation with EPA and Department of Planning,

Industry and Environment and stakeholders, including the Glebe Island and White Bay Community Liaison

Group and port operators, to ensure that the policy still meets the legislative framework and properly

addresses the challenges of the port of Glebe Island and White Bay.

Port Authority in consultation with EPA will review the vessel trigger noise level every three years. Further

detail on the review of the vessel trigger noise level is contained in Vessel Noise Guideline (Appendix F,

Section 6.3).

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 11

5 Policy application

The Port Noise Policy, for the first time, outlines an approach to manage all landside activities and vessels at

Glebe Island and White Bay in a single consistent approach.

For vessels this includes all new and existing operations that, prior to the policy, may or may not have had

noise criteria set in planning approvals or EPLs. For each of these vessel operations the policy provides a

mechanism for ongoing noise reduction and noise criteria.

For landside activities all existing and new landside activity noise levels will be evaluated individually and as

a whole. Many existing criteria, prior to the policy, permit noise levels that are higher than could reasonably

be expected for the operations. Landside criteria for all existing operators shall be reviewed so any criteria

applied to an individual operator only reflects a fair and reasonable value that a well managed site could be

expected to emit. This approach ensures that summed individual criteria and cumulative operational noise

levels for port landside operations do not exceed the cumulative noise limit. Over time, the criteria applied to

each individual operator will be reviewed after considering all reasonable and feasible noise mitigation that

could be applied to the operations which is likely to result in a downward trend to the cumulative noise limit.

All noise levels for vessels, landside activities and cumulative noise levels are presented in noise maps

(Appendix I).The intended application of the policy when implemented is illustrated by the following three

examples.

Example 1 – existing vessel operations with no noise limits

Previous situation (prior to policy)

A number of bulk shipping vessel operations, prior to the policy, do not have noise limits under EPLs or

planning consents.

Noise levels were unrestricted, causing impacts on community with limited ability to reduce impacts through

regulatory means.

New situation (under this policy)

Under the policy all bulk shipping vessels have a noise limit.

The policy has set this limit at 55dBA at night time with a 24/7 noise goal of 55dBA.

Over time this may be reduced.

Benefits

Vessel unloading noise levels are now limited to 55dBA for all berths.

Vessels now have achievable noise targets and in the longer term, review of the policy will aim to reduce this

limit while unloading.

Example 2 – existing vessel operations with noise limits and unloading

restriction

Previous situation (prior to policy)

Current restrictions for some operations have prohibited unloading between 10pm and 7am for some berths

if night time noise levels exceed 45 dBA while the vessel is at berth. This limit does not apply to other users

of the berth.

Noise levels from other operators at this berth have been measured up to 55dBA at night. Noise levels from

vessels subject to this unloading restriction regularly produce noise in the low to mid 50dBA range when not

unloading (for example from operation of vessel engines and fans). Restarting of unloading preparations

may produce loud events which cause sleep disturbance before 7am.

The resulting effect of the unloading restriction is to approximately double the number of days and nights

where a vessel is impacting the community.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 12

New situation (under this policy)

Under this policy, the vessel noise limit has instead been set at 55dBA while unloading. Vessels are sourced

that can unload at or less than 55dBA. This level is similar to many of the previous vessels when not

unloading.

Benefits

Loud sleep disturbance events from restarting unloading have been eliminated, as this no longer has to

occur to re-commence operations in the early morning.

The number of days a vessel is required to be at berth to unload has reduced by approximately 50%.

Assuming the number of vessels utilising the berth remain constant, this increases the number of days

without a vessel at the berth.

Daytime unloading noise levels are now reduced to 55dBA, where as previously noise levels were measured

up to 64dBA during the day.

Vessels now have achievable noise targets and in the longer term, review of the policy will aim to reduce this

limit while unloading.

Example 3 – new port operation

A new operation is proposed at the port and it will be required to obtain a planning approval. The following

steps would be undertaken by the proponent as part of the assessment process:

• Identify the type of vessel that would use the berth and the possible range of noise levels from this

vessel. Identify the median and upper 10

th

percentile noise levels of the proposed vessel noise. The

median becomes the vessel trigger noise level and criteria for a vessel.

• Identify the potential noise impact of the landside activity. If the new landside activity causes a

significant increase in noise and/or causes overall port cumulative noise limits to be exceeded, then

noise mitigation needs to be included as part of the development to limit noise increases and so that

total landside noise from the port is less than the cumulative noise limit.

• Port Authority will review the reasonableness of the proposed noise emission from the landside activity

and verify the maximum permissible noise levels for the landside activity for use in the environmental

assessment.

• The environmental assessment will assess the potential cumulative noise impact from the landside

activities with a median vessel and also an upper 10

th

percentile vessel to identify any required feasible

and reasonable noise mitigation. Guidance on feasible and reasonable is taken from the NPfI and the

policy. The landside activity (which may at times be undertaken in the absence of a vessel) assessment

will demonstrate compliance with the maximum permissible noise levels for the new activity and

cumulative compliance for overall port landside noise levels.

If approved, the new operation will need to comply with consent conditions and an EPL if relevant.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 13

6 Noise guidelines

The Vessel Noise Guideline (Appendix F) and Landside Precinct Noise Guideline (Appendix G) outline the

processes for setting and assessing noise criteria for port activities and communicating the outcomes to

community and other stakeholders. The following sections describe the rationale of these two guidelines and

how they will be implemented.

Where agreed with regulators and approval authorities the outputs of these guidelines may be incorporated

into the following for port developments:

• conditions in planning approvals

• Environment Protection Licences issued by the EPA.

The noise maps produced by implementing these guidelines may also be applied by approval authorities

when developing planning controls for residential and commercial developments encroaching on the port on

nearby land (Appendix I).

The environmental noise criteria in this policy aim to provide protection for noise sensitive receivers in the

areas surrounding Glebe Island and White Bay. Residential receivers are assessed for vessel and landside

noise outside the receiver at the residential property boundary or as defined in the EPA’s NPfI. Other

premises have internal noise criteria. These include schools, places of worship and hospitals (see the EPA’s

NPfI for additional detail and a complete list of receiver types).

Planning controls for residential and commercial developers on land near the port have internal noise criteria

for living areas and bedrooms.

6.1 Vessel Noise Guideline

Management of vessel noise is addressed in the Vessel Noise Guideline (Appendix F) which has been

developed by using Section 10 of the EPA’s NPfI to set a trigger noise level for vessels at berth based on

noise levels that may reasonably be achieved while minimising impacts on the community.

The requirement for vessels visiting Glebe Island and White Bay to comply with the trigger noise level is

included in access agreements for tenants and terms and conditions for ship operators. The specific vessel

noise operating protocol for each berth outlines the actions which are to be undertaken if a vessel exceeds

the trigger noise level. The noise levels will be measured at each berth when a vessel is present. Where

noise levels from the vessel exceed the noise trigger, the user will be required to ensure that the vessel can

subsequently meet the noise trigger by applying corrective action.

If compliance with noise triggers cannot be achieved on a repeated basis, operating restrictions will be

applied. Careful consideration should be given to applying unloading restrictions that increase the length of

stay as restrictions are not wholly effective in reducing noise levels. This is because vessels still produce

noise impacts when not unloading. A longer stay at berth generally increases overall noise exposure from

the vessel.

The approach of setting triggers for individual vessels is consistent with the approach that has already been

used to set noise targets for individual road and rail vehicles and aircraft (further detail is in Appendix D).

While similarities can be found in noise emission and management approaches that between industrial

operations and the landside activities at a port, noise emissions from vessels differ from the noise emissions

of vehicles within a typical industrial site, because (in the absence of this policy) they do not fall into either of

these two categories:

• captive and solely used within the site

• visitors to the site with individual noise targets set by other criteria or regulations.

This has historically made the management of vessel noise, and the prediction and modelling of overall port

noise, problematic.

The setting of a trigger level for vessels simplifies future noise predictions as it puts an upper limit on the

representative range in noise levels. This provides enough certainty to produce reliable noise maps that

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 14

illustrate relative noise impact from multiple vessels visiting the port over representative time periods. For

vessels at White Bay and Glebe Island the selected time periods for preparation of noise maps are 1 year,

and the three months of summer and winter to provide information on any seasonal variation. This mapping

technique with extended time period averages is used for road traffic noise, which use annual average traffic

volumes, and to produce Australian Noise Exposure Forecast noise maps for airports (see Appendix D).

The vessel trigger noise level should not be viewed as an amenity based criteria. The vessel trigger noise

level and upper 10

th

percentile level obtained in Appendix F informs the representative noise levels used to

assess the cumulative noise from an operation and an individual vessel at a berth as well as the whole port

in an environmental assessment or review. Appendix F recommends mitigation is considered based on

exceedance of specified target noise levels and exposure.

The Vessel Noise Guideline outlines how trigger noise levels from all berths across the port are used to

develop whole of port noise maps that illustrate annual and seasonal noise exposure by the port on

surrounding areas. These maps also include future projections for the port.

The vessel trigger levels were derived from median unloading noise levels (based on review and analysis of

available measured noise from vessels) and what is reasonable and feasible to achieve at the port due to

proximity to residences and current vessel design. In terms of overall noise, the trigger levels were reviewed

against and found to be similar to noise level criteria for other transportation noise sources in NSW and also

to some port criteria in some other jurisdictions (see Appendix B and Appendix D). However, the review

overall showed that noise criteria levels for port and vessel noise are inconsistent internationally and across

Australia.

6.2 Landside Precinct Noise Guideline

The Landside Precinct Noise Guideline adopts the concepts of noise management precincts outlined in the

EPA NPfI. A Noise Management Precinct enables an area with many proponents to operate as a single site

that is required to meet the amenity level, where feasible and reasonable. This approach simplifies

assessment and compliance by setting a single noise goal which all tenants must collectively meet.

The concept of a Noise Management Precinct will be introduced in all port tenant leases of Glebe Island and

White Bay from January 2021. Under each lease, each tenant has been allocated an individual maximum

permissible noise level which collectively will meet the assessment criteria for the precinct.

The guideline sets the processes for undertaking an environmental assessment within the Noise

Management Precinct for a port development and equitably allocates permissible noise emission and the

burden of noise mitigation to each proponent. It also outlines ongoing noise monitoring and compliance

requirements.

Precincts provide the flexibility to apply additional noise mitigation to an existing proponent if this is more

cost effective and practicable than just mitigating noise from a new proponent. If this mechanism is utilised,

the permissible noise emission for a proponent may change over time if a new proponent seeks approval to

operate within a port and it is more cost effective to additionally mitigate an existing proponent.

The Noise Management Precinct will not include the operations of construction projects and staging support

being carried out on Glebe Island and White Bay. This is because these activities are governed by their own

separate planning processes and noise criteria defined in planning approval conditions (not directly related to

port precinct criteria), and which are not anticipated to continue with port operations in the long term.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 15

6.3 Planning controls

The two guidelines outline the process for developing noise maps which may be used by approval authorities

to inform the preparation of planning controls for new developments that are encroaching on the port. These

controls could be considered by approval authorities to be adopted within statutory planning policies or

project approval conditions. Planning controls may be used to ensure that internal noise levels in new

buildings provide appropriate levels of amenity for their occupants. These controls are applied as internal

noise level criteria.

Achieving the internal noise criteria requires the developer to locate the building away from noise, construct

noise barriers or design the building façade to provide sufficient noise attenuation to meet the internal noise

criteria.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 16

7 Noise trigger levels and criteria

The following tables outline the initial vessel trigger noise levels and landside criteria established under this

policy using the Vessel Noise Guideline (Appendix F) and the Landside Precinct Noise Guideline (Appendix

G).

The Noise Standard (Appendix H) sets the current vessel trigger noise levels and the detailed allocation of

the landside noise criteria for individual port users. Note the vessel trigger noise levels will be periodically

reviewed to consider whether the triggers may be lowered to reduce overall port noise.

These noise levels assume that they have taken into consideration any annoying characteristics as defined

under the Vessel Noise Guideline and Landside Precinct Noise Guideline.

The 24/7 noise goal for an individual vessel at berth is 55dBA or less while unloading. Table 3 shows the

24/7 goal is applied in the night time as a vessel trigger noise level. In the daytime a plus 5dBA allowance is

applied to the 24/7 goal. The plus 5 dBA provides short term allowance for vessels that have to restrict night

time unloading rates to meet the night time 55dBA vessel trigger noise level.

The trigger level is applicable at the worst affected sensitive receiver at the time of commencing this policy.

Table 3: Vessel Trigger Noise Levels (external)

Environmental trigger

applied to vessels at

berth

Assessment

Location

Day (L

Aeq, 15hr

)

1

(7am to

10pm)

Night (L

Aeq, 1hr

)

(10pm to

7am)

Night (L

Amax

)

(10pm to

7am)

Glebe Island 1 and 2

Glebe Island 7 and 8

White Bay 3

White Bay 4 (non-cruise)

All sensitive

receivers near the

port

60 dBA

60 dBA

60 dBA

60 dBA

55 dBA

55 dBA

55 dBA

55 dBA

65 dBA

65 dBA

65 dBA

65 dBA

Note 1: This includes a 5dBA allowance in the short term for vessels that cannot meet the night time vessel trigger noise

level without restrictions to unloading speeds. The 24/7 goal is the median unloading noise level for vessels which is

applied as the night time vessel trigger noise level

Port Authority will review each vessel trigger noise level utilising the principles outlined in Appendix F, in any

case not reducing the vessel trigger noise level by more than 2dBA during each review period.

The currently anticipated ultimate noise trigger following multiple 2dBA (maximum incremental) reductions is

50dBA which is the anticipated minimum noise level that could reasonably be achieved by vessels at this

point in time. Any vessel noise reduction beyond 50dBA based on current technologies is not considered

feasible and would be expected not have measurable benefit given the existing background noise levels in

the community and other sources of ambient noise. This goal will be reviewed overtime with changes to the

ambient noise.

The cumulative noise limit is outlined in Table 4. These criteria represent the total amenity noise level that all

port landside activities collectively must not exceed following successive industrial developments where

feasible and reasonable. The precinct criteria are applicable at the worst affected sensitive receiver current

at the time of commencing this policy and are equivalent to the NPfI’s amenity criteria for an urban industrial

interface.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 17

Table 4: Port landside precinct noise criteria

Category

Assessment

Location

Day (L

Aeq, 11hr

)

(7am to 6pm)

Evening (L

Aeq, 4hr

)

(6pm to 10pm)

Night (L

Aeq, 9hr

)

(10pm to 7am)

External environmental

criteria applied to the

Noise Management

Precinct

All residential

land near the port

65 dBA

55 dBA

50 dBA

Internal environmental

criteria applied to the

Noise Management

Precinct

Other noise

sensitive

receivers

Refer to the NSW EPA’s NPfI, Table 2.2

Note the total amenity noise level currently permitted to be emitted from port landside activities may be less

than the cumulative noise limit as the cumulative noise limit is the maximum level following successive

industrial development. The total amenity noise level that may currently be emitted from the port is the

benchmark noise level. This is detailed further in Appendix G and Appendix H. Increases in the benchmark

noise level are only permitted where the noise increase from a new port development or redevelopment is

reasonable and the total noise level does not exceed the cumulative noise limit. Guidance on acceptable

noise level increases is taken from the NPfI.

The recommended minimum planning control (internal noise level) for new developments encroaching on the

port are shown in

Table 5. Future noise levels should be sourced from Appendix I.

Table 5: Recommended planning control (internal)

Category

Assessment Location

Day (L

Aeq, 1hr

)

(7am to 10pm)

Night (L

Aeq, 1hr

)

(10pm to 7am)

Planning control applied to

cumulative landside and

vessel noise

New residential developments

near the port

40 dBA

35 dBA

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 18

8 Management and mitigation of port noise

There are three distinct approaches used to mitigate noise from the port, each relating to either vessels,

landside activities or whole of port noise levels.

Underpinning each of these are contracts between the Port Authority and each of the port users, which

outline the noise criteria for vessels and landside activities with actions that will be undertaken if noise levels

exceed agreed levels.

Port Authority also plays an active role in reviewing and setting trigger levels for vessels in a collaborative

manner with stakeholders.

8.1 Noise monitoring

Port Authority will proactively monitor noise levels from vessels and measure collective noise levels from the

landside precinct. The results of noise monitoring will be reported on Port Authority’s website.

Actions will be undertaken by Port Authority where noise levels exceed vessel noise trigger levels or the

landside noise precinct criteria, as described in Section 8.1.1 and 8.1.2.

8.1.1 Vessel noise monitoring and management actions

Port Authority will measure the noise level for all visiting vessels and initiate actions, outlined in the operating

protocols, if exceedances occur. A first step will be informing the tenants and vessel operator that the vessel

exceeds the noise trigger level. This shall be identified by attended or automated noise measurement.

If the vessel is unable to immediately reduce noise, and Port Authority’s attended measurement confirms the

vessel is the noise source, then Port Authority will issue a corrective action notice to the vessel. The vessel

will then be required to prepare and implement a management plan to reduce noise before the next visit.

Significant ongoing exceedances on subsequent visits may result in a ban of the vessel.

The vessel operators of noisy vessels have the following options to avoid a ban of the vessel:

• successfully implementing a management and noise reduction plan

• mitigating the vessel

• selecting a quieter vessel for future visits.

The responsibility for addressing noise from specific vessels falls to the vessel operators and the overall

responsibility for repeated failure to comply with the operating protocols is with the tenant.

Further detail is provided in the Operating Protocols developed for each berth, which are published on Port

Authority’s website.

8.1.2 Landside precinct noise monitoring and management actions

Port Authority will undertake noise monitoring of the landside precinct and compare it with the benchmark

noise level for the precinct.

The operators of landside activities or owners of landside infrastructure are responsible for meeting noise

criteria. The operators and owners may be external organisations (generally tenants) or Port Authority.

If noise levels from landside activities exceed the precinct criteria, Port Authority will require landside

operators to verify and report on their noise emission. If a landside operator has exceeded their maximum

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 19

permissible noise level, they will be required to reduce noise from their landside activities to meet their

contractual commitments to Port Authority.

Under the principles of a noise precinct and the terms of the contracts between operators and Port Authority,

noise reduction may be undertaken for an operator’s own site or alternatively for another operators site if it is

more cost effective and there are no reasonable objections.

8.2 Vessel noise reduction

There are currently no international or national environmental design criteria for noise emissions from a

vessel to manage noise levels at nearby sensitive receivers. Outside this policy, the only noise requirements

are those introduced during a vessel’s design and construction stage for on-board safety and crew comfort.

Depending on the individual vessel, noise reduction may or may not be feasible for technical or economic

reasons.

Potential mitigation for existing vessels may include additional or upgraded silencers, improved ducting

design and attenuators for fans, pumps, generators and engines. While there are different types of silencers

and attenuators available, their design and location within the length of exhaust ducting needs to be tuned to

the noise source.

For engines and generators, key factors relating to noise are the operational revolutions per minute (rpm),

number of cylinders and capacity of the engine, particularly to reduce low frequency tonal noise.

There are greater opportunities to reduce noise during the design phase of new ships beyond the minimum

requirements for on-board comfort and safety, and this is the easiest time to incorporate mitigation

measures.

Due to space and access requirements, opportunities to retrofit additional noise mitigation to a given vessel

may be limited and can only be reviewed on a case by case basis.

8.3 Landside noise mitigation

The landside activities at White Bay and Glebe Island mostly relate to handling and processing passengers

and cargo including bulk dry and liquid goods. These landside operations are similar to the activities in an

industrial site, as are the potential mitigation options. These include:

• use of quieter plant and alternative material handling rates

• control of vehicle noise using silencing, speed restrictions, plant selection and smooth pavements

without potholes, bumps and abrupt changes in level

• operational restrictions including hours of operation and material processing rates.

• noise barriers such as acoustic sheds, partial enclosures and other forms

• at-receiver noise treatments.

Additionally, while a vessel is at berth, the vessel may:

• provide acoustic shielding to receivers on the seaward side

• act as a reflector to landside receivers

• mask noise from landside activities or significantly alter the background noise level.

8.4 Whole of port noise mitigation

Port Authority mitigates whole of port noise levels using various strategies. These include:

• strategic planning for permitted activities at various berths

• contractual arrangements with port users to limit noise

• setting of achievable noise triggers for vessels and criteria for landside activities

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 20

• whole of port noise monitoring

• implementing protocols should vessel or landside noise exceed the triggers and criteria set under this

policy

• periodic review of vessel trigger noise levels to consider reducing the level to quieter level.

Port Authority may consider additional noise mitigation where noise exposure is still significant after the

application of these strategies.

8.4.1 Feasible and reasonable noise mitigation

Noise mitigation will only be considered where it is ‘feasible and reasonable’ as defined in Fact Sheet F of

the EPA’s NPfI:

A feasible mitigation measure is a noise mitigation measure that can be engineered and is practical

to build and/or implement, given project constraints such as safety, maintenance, and reliability

requirements. It may also include options such as amending operational practices (for example,

changing a noisy operation to a less-sensitive period or location) to achieve noise reduction.

Selecting reasonable measures from those that are feasible involves judging whether the overall

noise benefits outweigh the overall adverse social, economic, and environmental effects, including

the cost of the mitigation measure.

1

The EPA’s NPfI requires that a consideration of ‘reasonableness’ must look at the range of feasible

measures to determine which measures are appropriate, having regard to a number of factors outlined in

Fact Sheet F:

• Noise impacts:

o existing and future levels, and projected changes in noise levels

o level of amenity before the development, for example, the number of people affected or annoyed

o the amount by which the triggers are exceeded.

• Noise mitigation benefits:

o the amount of noise reduction expected, including the cumulative effectiveness of proposed

mitigation measures, for example, a noise wall/mound should be able to reduce noise levels by at

least 5 decibels

o the number of people protected.

• Cost effectiveness of noise mitigation:

o the total cost of mitigation measures

o noise mitigation costs compared with total project costs, taking into account capital and

maintenance costs

o ongoing operational and maintenance cost borne by the community, for example, running air

conditioners or mechanical ventilation.

• Community views:

o engage with affected land users when deciding about aesthetic and other impacts of noise

mitigation measures

o determine the views of all affected land users, not just those making representations, through early

community consultation

o consider noise mitigation measures that have majority support from the affected community.

1

EPA NPfI (2017), Fact Sheet F: Feasible and Reasonable Mitigation www.epa.nsw.gov.au

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 21

There are additional factors to take into account when considering noise impacts for a port:

• noise impacts may be seasonal which lessens community annoyance for the same noise level

2

• noise impacts may be sporadic for a limited number of consecutive hours or days before respite

between vessel visits

• triggers for vessel noise should reflect what is reasonable for the operator in a national and international

context.

There are also considerations for an existing port:

• once constructed and operational, a port cannot be easily relocated

• ports are significant infrastructure constructed following substantial government investment

• a port requires specific geographical features to provide safe berthing for loading and unloading and

they are commonly extensively modified to provide sufficient water depth for vessels and cargo

operations through dredging and land reclamation

• transportation modes (such as road and rail) have usually been established to support the land

transport of passengers or bulk goods to and from the port

• EPA’s NPfI and superseded Industrial Noise Policy acknowledges:

o there are challenges for sites that predate the current noise policy to meet the latest noise criteria

o where it is not possible to meet the latest noise criteria, to instead consider the use of alternative

noise triggers that are practical to achieve with feasible and reasonable mitigation and within

constraints associated with the site. The alternative triggers are implemented with a noise reduction

strategy to reduce noise emissions towards the EPA policy criteria over a period of time.

8.4.2 Considerations for Glebe Island and White Bay noise mitigation

Glebe Island and White Bay have been port facilities for over 100 years following land reclamation and initial

construction of the wharves that are still used today. The wharves and other port infrastructure of Glebe

Island and White Bay are ‘existing infrastructure’ under the EPA’s NPfI and all superseded EPA noise

policies. Noise due to changes and intensification of port activities must also be assessed and managed.

When assessing noise criteria and considering any noise mitigation for Glebe Island and White Bay the

following reasonableness measures will be taken into account:

• the port infrastructure was constructed prior to any environmental noise criteria

• noise emissions from individual operators or proponents may be sporadic and/or seasonal which

means that annual, seasonal and weekly noise exposure may vary, with quieter periods between vessel

visits

• noise from an occupied berth may be reasonably consistent between different ship types or proponents

over a period of many decades

• management of noise requires strategic planning of the port as a whole to manage noise from the

individual operators. This requires individual proponents and operations to be located in places where

they will create the least conflict with surrounding land uses

• landside operations may be shielded by the ship so that the noise from these operations is not as

significant

• ports may be a natural amphitheatre limiting the effects of shielding, noting that vessel noise sources

range from 0.5m to at least 25m above the waterline and receivers are often elevated by topography.

2

Miedema, H.M.E. and Vos, H., 2004, Noise annoyance from stationary sources: Relationships with

exposure metric day evening night level (DENL) and their confidence intervals, The Journal of the Acoustical

Society of America, 116/1, pp 334 - 343

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 22

8.4.3 Berthing allocations

Minimising port noise involves an assessment of the current needs and uses of the berths at Glebe Island

and White Bay and active management of the berths matching the appropriate uses to the appropriate

locations. The primary current use for the berths at Glebe Island and White Bay is for the transportation of

bulk goods, such as cement, gypsum, sugar, salt and tallow.

Vessels carrying bulk goods typically require overnight stays (24 hours or more) to provide sufficient time to

unload or load cargo. The location of these activities within the port are best suited to the berths closer to

ANZAC bridge at Glebe Island and berths 3 and 4 at White Bay, which already have a reasonable level of

background noise due to nearby roads. Many of the residences in these noisier locations (particularly recent

developments in Pyrmont and in Buchanan Street, Balmain) have been approved and designed to address

night time noise levels from ANZAC bridge and the port.

The preferred location for the cruise ships is at White Bay berths 4 and 5 as the number of overnight visits

from cruise ships is currently relatively low compared to bulk vessels at other berths and unlikely to

significantly increase in the future. A noise attenuation program to mitigate noise from cruise ships

commenced in October 2018 for White Bay Cruise Terminal, and extended to mitigate noise from cruise

ships at White Bay berth 4 in January 2020.

Port Authority has a berthing allocation process which defines the considerations made in allocating ships

not servicing Port Authority’s usual port operators known as ‘infrequent visitors’ to berths at White Bay and

Glebe Island. The process also sets the minimum expectations of behaviour (in relation to noise generating

operations) required from these ships while utilising these berths. The aim is to provide guidance to ensure

that the most appropriate available location is selected for infrequent visitors thereby minimising the impacts

of these ships’ activities on the local community.

Infrequent visitors currently include:

• vessels discharging project cargo (including equipment required for construction projects within

Sydney)

• vessels in need – ships needing berth space at short notice, for example, to carry out emergency

repairs, obtain refuge from adverse weather conditions and any ship under detention.

The berth allocation process defines the allocation of berths to infrequent visitor ships based on:

• availability

• suitability

• proximity to residents

• whether nearby residential areas are attenuated for noise

• equitable distribution.

8.4.4 Noise barriers

Noise barriers are generally not considered feasible and reasonable to reduce noise from vessels,

particularly in Glebe Island and White Bay because:

• residences and vessels noise sources are usually elevated at White Bay and Glebe Island, which limits

the effectiveness of practical noise barriers. Noise barriers would need to be more than 30 metres in

height

• there is limited land available between the vessel and residence for construction of a barrier

• barriers may impact water views from the residential properties.

Glebe Island & White Bay Port Noise Policy Port Authority of New South Wales | Page 23

8.4.5 Shore power

Shore power is often suggested as a solution to reduce ship noise. However noise emission from a vessel

would still continue as shore power only eliminates the need for generators and not the on-board systems