IN SUPPORT OFSPONSORED BY

Connecting

learners: Narrowing

the educational divide

The benets from, and barriers to, improved

school connectivity and access to digital learning

2

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Foreword

The path of human progress is marked by milestones created when a

relevant technology arrives at the right time to meet or drive forward a

compelling collective need – just think about Johannes Gutenberg and

the printing press, Grace Hopper and computer programming, and Tim

Berners-Lee and the World Wide Web.

We have now reached another of these technology milestones,

with digital connectivity increasingly underpinning global society.

While education has for decades been greatly challenged by the

digital divide, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the digital

transformation, creating opportunity from deep adversity. With

schools closed, millions of families around the globe transitioned

overnight to remote learning. Digital experiences, enabled

by connectivity and quality content, have become vital for

students and teachers to continue the pursuit of knowledge.

While disruptive, this watershed has allowed a glimpse of what is

possible when technology is used in innovative ways to provide learning

opportunities for children and young people, wherever they are.

But much work remains for a vision of universal digital connectivity

and learning to be realised. This report by The Economist Intelligence

Unit underscores the importance of accelerating gains in infrastructure

and education in tandem. It quantifies how connecting schools is key to

improved learning outcomes and more prosperous economies, finding

that a 10% increase in school connectivity can increase the eective

years of schooling for children by 0.6%, and GDP per capita by 1.1%.

It also reveals that, in addition to the need to improve infrastructure,

teachers and students must have the support and tools required to

fully realise the new possibilities that school connectivity brings to

learning. This is true in both developing and developed countries, and

in both urban and rural areas. The digital divide is a challenge for all

societies. Moreover, the benefits of such investments are not limited to

schoolchildren: connected schools serve as community focal points for

broader learning and development, as well as enhancing the quality of

digital literacy among community members.

3

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Collaboration across sectors, such as UNICEF’s partnership with

Ericsson, is key to accelerating and sustaining change. We are proud

to be working together to support the global Giga initiative, which was

launched in 2019 by UNICEF and the International Telecommunication

Union (ITU). Its aim is to connect every school worldwide to the

internet by 2030. Ericsson’s resources and expertise are accelerating

the collection, analysis and visualisation of data in real time, supporting

UNICEF in mapping school connectivity in 35 countries by the end of

2023. This will be a fundamental step toward Giga’s ambitious goal of

connecting every school around the globe within a decade.

The strengthening of universal connectivity is a critical step towards

providing access to digital learning. But our eorts cannot stop there.

That is why UNICEF has launched the Reimagine Education initiative,

with the aim of providing every child and young person access to

world-class digital learning to help them develop the skills needed to

leapfrog to a brighter future. With its focus on school connectivity, the

Giga initiative serves as one of the key pillars of Reimagine Education.

Through further partnership and collaboration, Reimagine Education

builds on improved connectivity, aordability of data, access to devices,

and engagement with young people to apply this transformative vision

in the way we deliver education.

We have a responsibility to accelerate digital inclusion and build a

sustainable future for generations of students to come. We encourage

governments, public institutions, industry and thought leaders to join

us in true public–private partnership. This will provide the leadership

required to achieve quality digital learning, meaningful connectivity,

and access to opportunity for every child.

Börje Ekholm

CEO, Ericsson

Henrietta Fore

UNICEF Executive Director

4

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Contents

Foreword 2

About this report 5

Executive Summary 8

. Introduction 10

. A shift in focus: from education quantity to education quality 11

. Connecting schools, bridging gaps 23

. Beyond the individual: The socioeconomic impacts of school 32

connectivity and access to digital learning

. What’s to gain from connecting schools? 40

. So, where do we go from here? 52

Appendix A: Country profiles 67

Brazil 67

El Salvador 70

Kyrgyzstan 72

Niger 74

Sierra Leone 76

United States 78

Appendix B: Methodology note 80

5

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

About this report

Alejandro Ganimian

New York University, Assistant Professor

of Applied Psychology and Economics

Alex Wong

International Telecommunication Union (ITU),

Chief, Special Initiatives, and ITU Giga Co-Lead

Borhene Chakroun

UNESCO, Director, Division for Policies

and Lifelong Learning Systems

Christopher Yoo

University of Pennsylvania, John H. Chestnut

Professor of Law, Communication, and

Computer and Information Science and

Director of the Center for Technology,

Innovation and Competition

Eric Kimenyi

African Institute of Mathematical Sciences

(AIMS), Programme Manager, Teacher

Training Programme (TTP) Rwanda

Jane Con

Internet Society, Senior Vice

President for Internet Growth

Jonathan Birdwell – Senior project director

Jeremy Kingsley – Project director

Shivangi Jain – Project manager and

lead economist

Mrigansh Jain – Economist

Anand Kashyap – Researcher

Connecting learners: Narrowing the educational divide is an Economist Intelligence Unit

(EIU) report commissioned by Ericsson. The findings are based on a literature review, expert

interviews and econometric modelling conducted by The EIU between January and April 2021.

A more detailed description of our methodology is provided in Appendix B. The EIU bears sole

responsibility for the content of this report. The findings and views expressed do not necessarily

reflect the views of the sponsor.

We would like to extend our gratitude to Ericsson and UNICEF for their invaluable advice and

guidance throughout the project. The report has been produced by a team of researchers,

writers and editors, including:

Macke Raymond

Stanford University, Director of the Center for

Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO)

Mario Franco

Millenium@EDU SUSTAINABLE

EDUCATION, Chairperson

Michael Trucano

World Bank, Senior Education &

Technology Policy Specialist and Global

Lead for Innovation in Education

Miguel Brechner

Plan Ceibal Uruguay, Founder

and former President

Radhika Iyengar

Columbia University, The Earth

Institute, Education Sector Director

Tim Unwin

UNESCO Chair in ICT4D and Royal

Holloway, University of London,

Emeritus Professor of Geography

For any enquiries about the report

please contact:

Shivangi Jain

The Economist Intelligence Unit

E: shivangijain@eiu.com

Interviewees

Our thanks are due to the following people for their time and insights:

6

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

About The Economist Intelligence Unit

The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) is the research arm of The

Economist Group, publisher of The Economist. As the world’s leading

provider of country intelligence, it helps governments, institutions

and businesses by providing timely, reliable and impartial analysis

of economic and development strategies. Through its public policy

practice, The EIU provides evidence-based research for policymakers

and stakeholders seeking measurable outcomes, in fields ranging from

gender and finance to energy and technology. It conducts research

through interviews, regulatory analysis, quantitative modelling and

forecasting, and displays the results via interactive data visualisation

tools. Through a global network of more than 650 analysts and

contributors, The EIU continuously assesses and forecasts political,

economic and business conditions in more than 200 countries. For

more information, visit www.eiu.com.

About Ericsson

Ericsson provides high-performing solutions to enable its

customers to capture the full value of connectivity. The

Company supplies communication infrastructure, services and

software to the telecom industry and other sectors. Ericsson

has approximately 100,000 employees and serves customers

in more than 180 countries. Ericsson is listed on Nasdaq

Stockholm and the Ericsson ADS trade on Nasdaq New York. The

Company’s headquarters are located in Stockholm, Sweden.

Ericsson is sponsoring this report in support of the Company's

global partnership with UNICEF, which is contributing

to mapping school connectivity in 35 countries.

About UNICEF

UNICEF promotes the rights and wellbeing of every child, in

everything we do. Together with our partners, we work in 190

countries and territories to translate that commitment into practical

action, focusing special eort on reaching the most vulnerable and

excluded children, to the benefit of all children, everywhere.

For more information about UNICEF and its

work for children, visit www.unicef.org.

Follow UNICEF on Twitter and LinkedIn.

UNICEF does not endorse any company, brand, product or service.

7

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Why school connectivity?

Even in the most remote, hard-to-reach areas, there are

schools around which entire communities gather, not only

for learning, but also for community-wide access to health

and emergency services. However, nobody knows how many schools there are in the world,

or where they all are. This information gap means that we cannot identify where to deploy

resources—including the digital resources so necessary in an increasingly digital world.

Launched by UNICEF and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in 2019, Giga

1

is a global initiative to connect every school to the internet, and every young person to

information, opportunity, and choice. Schools, for Giga, are not only a place for learning

and connecting, but also a focal point, a countable unit, to craft business cases to connect

unconnected schools and communities. Giga starts by mapping the location and real-time

connectivity status of every school in the world, to identify connectivity gaps and assess

demand. With this data, it works with industry and governments to identify best possible

connectivity solutions and build sustainable models for finance and service delivery—

so that every young person and their entire surrounding community can access digital

solutions and meaningfully participate in and contribute to their own empowered future.

Reimagine Education

Under the leadership of UNICEF, with Generation Unlimited

and Giga, the Reimagine Education initiative seeks to radically

scale up digital learning solutions. It aims to enable every

child and young person—some 3.5 billion by 2030—to access world-class digital

learning solutions which can build the skills they need to leapfrog to a brighter

future. The initiative operates through five key interconnected components:

• World-class digital learning solutions: Personalised learning which provides every

child and young person with a modern education that: is child-centred, self-paced,

individualised, relevant to the child’s context and language-appropriate; is skills-

based (foundational, transferable, digital, entrepreneurial and job-specific); promotes

universality by reaching all children and young people including the most marginalised;

and employs appropriate technology including digital, low/no tech, and hybrid solutions.

• Connectivity: Connecting every school, child and young person to the internet and to

choice and opportunity;

• Aordability of data and content: Making digital learning more aordable to enable

access by every child and young person;

• Access to devices: Providing devices for children and teachers/facilitators so that

marginalised children and young people can access the best available digital learning

solutions; and

• Young people’s engagement: Young people and volunteers as co-creators of solutions

and who can oer support with advocacy, accountability, and scale.

https://gigaconnect.org/

8

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Executive summary

In the last few decades, amid the widespread

adoption of digital devices including laptops

and mobile phones, the promise held by

digital connectivity for school-age children

has become increasingly evident. By providing

access to a wealth of resources and enabling

new forms of learning, such as through

adaptive learning platforms, access to the

internet and digital learning has played an

important role in enhancing the quality

of education globally. Improved learning

outcomes proliferate through adolescence

and adulthood, leading to a wider range of

higher education and career opportunities.

Ultimately, these benefits to individuals are

reflected in terms of higher incomes, better

health and improved overall well-being.

But the benefits from school connectivity and

digital learning don’t stop at the individual.

Improvements in the quality of education

have been consistently demonstrated to drive

economic growth through spillover eects: a

well-educated workforce is more likely to be

innovative and foster groundbreaking ideas,

leading to economic development and job

creation. To the extent that school connectivity

can enhance the quality of education—when

supplemented by other measures which

enable the eective use of the connectivity,

such as access to devices, the availability

of relevant content, and the provision of

support and tools to teachers and students

to eectively integrate technology into

educational practice—the same eects hold.

Beyond the long-run economic gains derived

through education improvements, school

connectivity also enables community

development, thereby generating additional

impacts. Connecting schools can serve to close

both the educational divide and the digital

divide. Schools are not only places where

children learn, but are also often community

hubs—places where people vote, where public

resources (like vaccines) are administered, and

where people shelter during natural disasters,

among other uses. Providing connectivity to a

school is a way to empower children with access

to world-class digital content, but it is also a

means to enable local entrepreneurship, provide

access to online banking, improve information

channels during emergencies or pandemics,

and open doors for employment through digital

platforms and the gig economy. It is through

this lens that school connectivity becomes an

important focus for achieving broader social and

economic goals in communities on a global scale.

School connectivity and access to digital

learning benefit individuals and society. But the

paths to deriving these benefits are complex.

To better understand these channels through

which school connectivity can impact on

learning and socioeconomic outcomes, The

EIU constructed an economic model. Our

analysis found that increasing levels of school

connectivity can improve both—quantitatively,

a 10% increase in school connectivity

2

can

increase the eective years of schooling for

children by 0.6%, and GDP per capita by 1.1%.

In Niger, for example, this could mean that

matching school connectivity levels to Rwanda—

with the highest school connectivity level among

developing countries—and Finland—with the

highest school connectivity level globally—

could increase eective years of schooling

3

by over 10% from 2.7 years. We calculate that

this could boost Niger’s GDP per capita by

up to 20% by 2025 (from projected GDP per

capita of US$550 in 2025 to up to $660).

Measured using the World Economic Forum’s ‘Internet Access in School index

Measured using the World Bank’s learning-adjusted years of schooling indicator which provides a measure of educational quality by adjusting the

average of schooling attained by the learning outcomes achieved.

9

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

In developed countries, on the other hand,

the challenge is less in terms of access to

connectivity in schools, and more in terms of

the quality of this connectivity. In the United

States, for example, while 99% of schools are

connected to fibre infrastructure to access the

internet, the speed of internet connection varies

substantially across states. We find that simply

improving the bandwidth per student across

states could increase national GDP by between

0.4% and 5.5%. A further major challenge with

regard to connectivity in the United States

is the so-called “homework gap”—the lack of

connectivity available to students outside of

schools, which leads to a divergence in the

performance on homework and subsequent

educational performance between students

with and without access. Addressing this

challenge could stimulate even further,

potentially more significant, economic gains.

While there are substantial potential gains on

oer from increasing school connectivity—

both for individuals and wider society—

making these a reality is easier said than done.

First, despite the benefits it can oer, school

connectivity levels remain low in many parts

of the world. This is driven by a number of

factors on both the supply and demand sides,

including investment barriers to building

infrastructure to connect hard-to-reach areas,

as well as challenges in the aordability of

connectivity for segments of the population.

Furthermore, obtaining access to the internet

alone does not guarantee that students

and teachers will be able to translate

this into academic benefits, or that these

benefits will subsequently generate wider

socioeconomic benefits. School connectivity

is a necessary precondition, but is only one

piece of the puzzle for achieving the gains.

So, what needs to happen next? This

report, based on the input and insights

of experts, identifies four priorities:

1. Collaboration is key. A holistic strategy—

with cross-government and private sector

collaboration—is needed to coordinate

eorts across stakeholders to overcome

barriers to school connectivity and access

to digital learning tools, and to enable their

eective integration with education systems.

2. Accessibility and aordability. Building

infrastructure to enable access to the

internet is the starting point for beginning

to realise the benefits it can oer. But

having the option to access the internet

is dierent to being able to access it in a

meaningful way—poor quality and high cost

can act as roadblocks. Working together,

governments, businesses and telecom

providers should aim to continually improve

the quality and aordability of connectivity.

3. Embedding the use of the internet

and digital tools in education. Once

aordable access to school connectivity

and digital learning has been achieved,

it must be eectively integrated into

curricula. This requires a change in the

approach to delivering education. It

also requires that teachers are trained to

deliver through these new approaches,

and that they have the tools to do so.

4. Protecting children online. While the

expansion of school connectivity and

access to digital learning come with

numerous learning opportunities for

children, they can also open up the door

to child abuse and exploitation. These

significant risks associated with the

expansion of internet access can often

create resistance to its use in education

from parents and teachers. Managing these

significant risks to enable the safe and

secure use of the internet will be important

in leveraging the benefits it can oer.

10

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

. Introduction

The link between education and socioeconomic

development is well-evidenced. As a result,

education policy is a priority for most

governments, and policymakers often have

two broad levers at their disposal: increasing

the quantity of education, and improving its

quality. While there still remains a gap between

the quantity of education across countries

(measured by average years of schooling), it

is rapidly closing and will reach a natural limit.

Improvement in the quality of education,

however, is boundless, and holds greater

scope for the influence of policymakers.

Improving internet connectivity and access

to digital learning in schools is becoming

increasingly essential in the context of education,

both from a quantity and quality perspective.

When it is aordable and accessible, with the

relevant content, it not only enables more

children to access education without placing

additional burden on teachers or driving

down quality by increasing classroom sizes,

it also has significant quality implications

by expanding access to a wide range of

educational resources, connecting students

to the best educational content and the best

teachers around the world at the click of a

button. In the context of COVID-19, access

to the internet for schoolchildren has allowed

many to continue to learn despite school

closures. At the same time, the pandemic has

highlighted the challenges posed by a lack of

connectivity. If anything, it has acted as an

accelerator for the integration of the internet

within education and can pave the way for

reimagining education systems across the world.

In this report, we explore the role of the

internet and digital tools in education, the

benefits that expansion of school connectivity

can bring to individuals and to societies,

and the challenges not only in terms of

increasing access but also in managing any

negative consequences of this. The report

is based on expert interviews, an extensive

literature review and bespoke economic

analysis to assess the potential gains from,

and challenges to, improved school internet

connectivity and access to digital learning.

• In section 2, we discuss the internet

in the context of education

• In section 3, we explore the benefits to

students from having access to the internet

• In section 4, we identify the wider

socioeconomic spillover eects

from school internet connectivity

and access to digital learning

• In section 5, we quantify the potential

economic gains from expanding school

connectivity in selected countries

• In section 6, we discuss how policymakers,

educational institutions and telecoms

providers can work together to

facilitate, leverage and manage

better internet connectivity and the

use of digital tools in education

11

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

While increased years of schooling can

result in higher labour market returns, the

magnitude of the returns depends also on

the interplay between demand and supply

forces in the labour market. If the demand

for educated labour is low relative to supply,

then the returns to education will similarly

be low. In urban China, for example, the

returns to education rose from 4% for each

additional year of schooling in 1988 to 10% in

2001. Most of this increase was attributable

to institutional reforms that increased the

demand for skilled labour.

9

These findings

highlight the intricate link between education

and economic performance, and vice versa.

The private returns to education go beyond

the financial benefits from increased labour

market earnings. Studies have, for example,

shown a link between maternal education

and child health through the knowledge

acquired by mothers—each additional year

of female primary schooling is estimated

to be associated with approximately

six fewer deaths per 1,000 live births.

10

Higher income levels can also allow for an

overall improvement in quality of life.

Education: A driver of

economic growth

There is no denying the powerful link

between education and economic growth.

Education is associated with a wide range

of benefits, not only to individuals receiving

education but also to society at large.

At the individual level, numerous studies

have sought to explore what is known as

the “private return” to education.

4

A more

educated individual is rewarded in the labour

market for their greater productivity—their

prize is a higher wage. According to an OECD

report, The Economic Impacts of Learning

Losses,

5

data shows that each additional

level of educational attainment is associated

with improved labour market outcomes

for individuals. The report observes that

individuals with higher levels of education

are more likely to find employment, remain

employed, learn new skills on the job and

earn more over their working life relative to

those with lower levels of education. The

Mincer equation, quantifies this relationship

between years of schooling and subsequent

earnings

6

—analysis suggests that every

additional year of schooling can increase the

earnings potential of an individual by 5–8%.

7,8

. A shift in focus: From education

quantity to education quality

Canals, C. (2017), “Education and economic growth”. https://www.caixabankresearch.com/en/economics-markets/labour-market-demographics/

education-and-economic-growth#:~:text=Education%20directly%20affects%20economic%20growth,as%20well%20as%20their%20quality.

Hanushek, E. and Woessmann, L. (2020), “The Economic Impacts of Learning Losses”, OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/The-economic-

impacts-of-coronavirus-covid-19-learning-losses.pdf

Mincer, J. (1974), “Schooling, experience and earnings”, NBER. https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/schooling-experience-and-earnings

Patrinos, H. (2016), “Estimating the return to schooling using the Mincer equation”, IZA World of Labour 2016:278.

https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/278/pdfs/estimating-return-to-schooling-using-mincer-equation.pdf

Card, D. (1999), “The causal effect of education on earnings”, Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 3.

https://eml.berkeley.edu/~card/papers/causal_educ_earnings.pdf

Zhang, J. et al (2005), “Economic returns to schooling in urban China, 1988 to 2001”, Journal of Comparative Economics 33 (2005) 730-752.

http://www.agrod.com/frontier/references/Zhang.2005.EconomicReturns.JournalOfComparativeEconomics.Vol33.p730.pdf

Angrist, N. et al (2018), “Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS)”, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 8591.

http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/243261538075151093/pdf/WPS8591.pdf

12

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

education and the contribution it can make to

achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development

Goals such as reducing hunger and poverty

levels, achieving greater gender equality,

and enabling a transition to clean energy.

14

Economic theory suggests that individuals

discount these wider societal benefits of

education, resulting in “under-consumption”,

or less education than would be socially

optimal.

15

Hence, education policy forms

an important component of public policy

and accounts for a significant share of

government expenditure across the world

in order to expand access to education and

reap its economic benefits—globally, public

sector expenditure on education accounted

for 4.5% of total GDP in 2017, reaching

over 5% on average in OECD countries

and over 7% in the Nordic countries.

16

The virtuous cycle of education

The contribution of education to sustainable economic development

Source: EIU research

But the benefits of education don’t stop

at the individual—there are also spillover

eects. A more educated youth population

leads to a more educated, skilled and

productive workforce which is more capable

of innovation and fostering groundbreaking

ideas. This contributes to more economic

development and facilitates a virtuous cycle

of: more income, more spending, more

jobs, more economic development, and

back to more income. Aghion et al. (2009)

show this relationship in the context of the

United States,

11

while others have provided

cross-country evidence.

12

A 2012 study by

UNESCO found that for every US$1 invested

in education, US$10–15 can be generated as a

return to the investment in economic growth.

13

A more recent 2018 programme conducted

by the FT with Credit Suisse illustrated the

various multiplier eects of investment in

The virtuous cycle of education

The contribution of education to sustainable economic development

Increased

education

Increased individual

incomes

Increased consumer

spending

Increased economic

development

Increased

number of jobs

Aghion, P. et al (2009), “The causal impact of education on economic growth: Evidence from U.S.”.

https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/aghion/files/causal_impact_of_education.pdf

Romer, P. (1989), “Human capital and growth: Theory and evidence”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 3173.

https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w3173/w3173.pdf

UNESCO (2012), “Youth and skills: Putting education to work”. Global Education Monitoring Report Team.

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000218003

“Education: The multiplier effect”. https://channelsftcom/thevalueofknowledge/infographic/

Misra, S. and Ghadai, S. (2015), “Merit Goods, Education Public Policy– India At Crossroads”, Journal of Education and Practice, ISSN 2222-1735,

Vol.6, No.12, 2015. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1080710.pdf

Based on World Bank data available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.XPD.TOTL.GD.ZS

13

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Individual/family Community/society

Monetary • Higher probability of

employment

• Greater productivity

• Higher earnings

• Reduced poverty

• Higher productivity

• More rapid economic

growth

• Poverty reduction

• Long-run development

Non-monetary • Better health

• Improved education and

health of children/family

• Greater resilience and

adaptability

• More engaged citizenship

• Better choices

• Greater life satisfaction

• Increased social mobility

• Better-functioning

institutions/service delivery

• Higher levels of civic

engagement

• Greater social cohesion

The importance of not only

educational quantity, but quality

While improving access to education and

increasing the number of years of education

every child receives are important, the scope

of education policy to influence this is limited

beyond a certain point. Although access to

even basic education remains alarmingly

low in many parts of the developing world,

the average years of education across the

world have been growing steadily at a rate

of 1.3% each year since 1990, and reached

a global average of 8.5 years in 2019.

18

As

access to education continues to grow,

focus has been shifting towards enhancing

the quality of education being provided.

The benefits of education

The monetary and non-monetary benefits to individuals and societies

Source: EIU research; World Bank

17

Angrist, N. et al (2018), “Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS)”, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 8591.

http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/243261538075151093/pdf/WPS8591.pdf

UNDP Human Development Reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/103006#

14

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Schooling and education are not synonymous—

the education or learning from one year

of schooling varies substantially across

countries as, even though the quantity of

education remains the same, the quality

varies.

20

Research has found that what matters

more for the individual and economy-wide

benefits associated with education is not the

number of years of schooling, but its quality.

In fact, research goes as far as to suggest that

“without improving school quality, developing

countries will find it dicult to improve their

long run economic performance.”

21

Moving

beyond quantitative measures of schooling,

new indicators are therefore now combining

these measures with measures of the quality

of education. The learning-adjusted years of

schooling (LAYS) indicator introduced by the

World Bank, for example, adjusts the number

of years of schooling attained by children

on average in each country for the learning

achieved through this schooling, according to

average performance across standardised tests.

At the individual level, analysis by Hanuschek

et al. (2015) finds that measures of educational

quality such as numeracy and reading

proficiency explain dierences in earnings

between individuals even after accounting for

any dierences in years of schooling.

22

Similarly,

at the economy-wide level, test scores which

reflect educational quality are found to be

associated with more rapid economic growth.

In fact, years of schooling no longer seem to

influence economic growth once quality is

accounted for.

23

It seems, therefore, that what

UNDP Human Development Reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/103006#

Angrist, N. et al (2018), “Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS)”, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 8591.

http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/243261538075151093/pdf/WPS8591.pdf

Grant, C. (2017), “The contribution of education to economic growth”. Institute of Development Studies.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b9b87f340f0b67896977bae/K4D_HDR_The_Contribution_of_Education_to_Economic_Growth_Final.pdf

See Angrist, N. et al (2018), “Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS)”, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 8591.

http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/243261538075151093/pdf/WPS8591.pdf

Angrist, N. et al (2018), “Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS)”, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 8591.

http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/243261538075151093/pdf/WPS8591.pdf

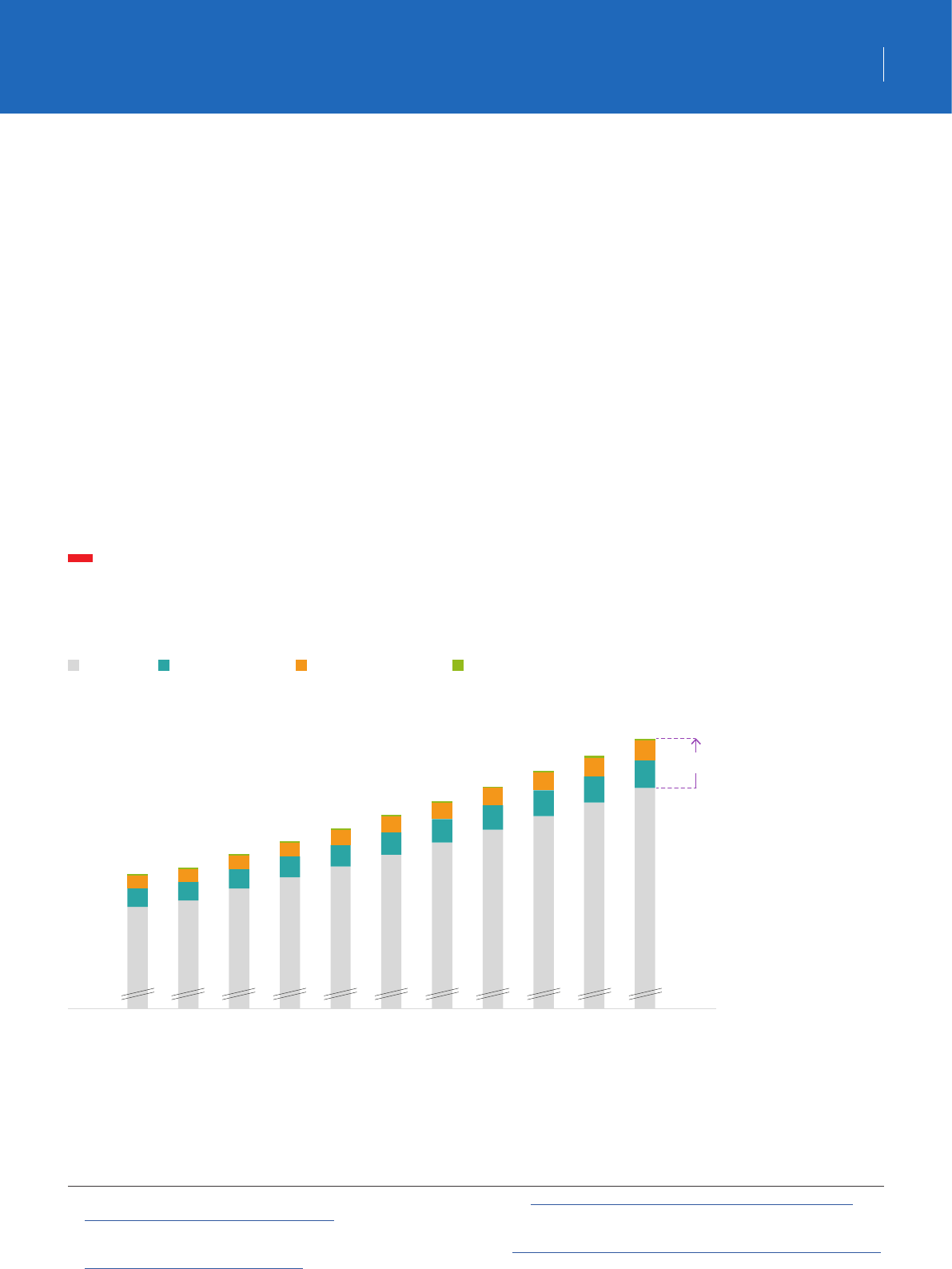

Growth in education quantity

Average years of schooling across the world (1990-2020)

0

2

4

6

8

1

0

1

2

1

4

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 20

20

Very high human development High human development

Medium human development

Low human development World

Growth in education quantity

Average years of schooling across the world (1990-2020)

Source: United Nations Development Programme

19

15

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

• Learning styles and teaching approaches.

Approaches to delivering learning have been

rapidly evolving over the past decades, with

a growing focus on tailored learning to match

individual requirements. Education experts,

Neil Fleming and Coleen Mills, developed

the VARK learning model which identified

four types of learner, acknowledging the

dierent approaches required to maximise

learning for each: visual learners, auditory

learners, reading/writing learners and

kinesthetic learners.

26

Similarly, personality

types such as introversion and extroversion

can impact learning preferences and the

retention of information. In Susan Cain’s

book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in

a World that Can’t Stop Talking,

27

one of

the critical dierences identified between

introverts and extroverts is that extroverts

tend to get their energy from social

interaction, while introverts gain energy

from quiet spaces and a time to think and

reflect alone. Hence, to maximise learning

outcomes we need teaching methods that

are engaging, inspiring and eective for all.

matters more for individual and economic

development is not how much schooling is

received but how good that schooling is.

So if the quality of education is really what drives

the benefits that it creates, the key question

then becomes: How can we ensure academic

excellence? Research has identified a number of

factors which influence the quality of education

and the learning outcomes it can generate:

• Levels of support and degree of student–

teacher interaction. The amount of support

and direct teacher interaction provided to

students can play an important role in learning

outcomes. The impact of class size has, for

example, been widely studied. Two seminal

papers provide evidence of the impact of

smaller class sizes on learning quality: Project

STAR and a 1999 analysis of Israeli schools

by economists Joshua Angrist and Victor

Lavy. Using a regression model, Angrist and

Lavy show that reducing class size induces

a significant and substantial increase in test

scores for fourth and fifth graders (students

typically between the ages of 9-11).

Project STAR (the “Tennessee Study”)

From 1985 to 1989, 11,600 Tennessee students from kindergarten to third

grade were randomly assigned to three class-size categories: 13–17 students,

22–25 students, and more than 25 students. An average student assigned to

the smallest classes had a reading score nearly 8% higher than students in the

medium-sized classes, and an average maths score which was 9% higher.

24

Education economists Alan Krueger and Diane Schanzenbach further analysed Project

STAR’s results to assess the long-run implications for students. They concluded that

reducing class sizes from 22 to 15 students has a 5.5% return in annual benefits.

25

Achilles, C. (2008), “Tennessee’s Student Teacher Achievement Ratio (STAR) project”, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=hdl:1902.1/10766

Krueger, A. and Schanzenbach, D. (2000), “The Effect of Attending a Small Class in the Early Grades on College-Test Taking and Middle School Test

Results: Evidence from Project Star”, Princeton University, Industrial Relations Section Working Paper No. 427.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=223492

University of Kansas, “4 Different Learning Styles You Should Know: The VARK Model”.

https://educationonline.ku.edu/community/4-different-learning-styles-to-know#:~:text=These%20different%20learning%20

styles%E2%80%94visual,understand%20their%20own%20learning%20preferences.

See Shulman, R. (2018), “10 Ways Educators Can Make Classrooms More Innovative”.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/robynshulman/2018/11/19/10-ways-educators-can-make-classrooms-more-innovative/?sh=15f0e6c67f87

16

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

In his research, John Hattie synthesised

the findings from over 500,000 studies

which measure the impact of dierent

teaching styles and approaches

on student achievement.

28

• Complementary learning tools. In

addition to the degree of interaction

with educators and the teaching styles

adopted, the tools used to support

learning can also play an influential role in

the ability of students to gain knowledge

through learning. Historically, teaching

has evolved from the teacher being the

primary source of knowledge to this being

supplemented by textbooks.

Today, in

many parts of the world, textbooks are also

rapidly being replaced by digital learning

tools such as electronic textbooks

29

and

other online resources ranging from

basic use of the internet to gain access to

information to sophisticated technologies

and advanced software that use artificial

intelligence to deliver tailored learning

content.

30

While there are drawbacks to

these technologies, not least in terms of

access and aordability, in many cases

they have been found to enhance the

quality of learning through improving the

learning experience and providing easy

and up-to-date access to information.

31

Hattie J (), “Teachers make a difference, what is the research evidence?”, Australian Council for Educational Research ACER).

https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=research_conference_2003

Chen, G. (2020), “Public Classrooms Say Goodbye Textbooks, Hello e-Texts”. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/blog/public-classrooms-say-

goodbye-textbooks-hello-e-texts

Ross, T. (2015), “The Death of Textbooks?”. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/03/the-death-of-textbooks/387055/

Chen, G. (2020), “Public Classrooms Say Goodbye Textbooks, Hello e-Texts”. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/blog/public-classrooms-say-

goodbye-textbooks-hello-e-texts

17

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Enhancing education quality

The cost and eectiveness of alternative means

to improve the quality of education

Source: Education Endowment Foundation (2018)

32

, EIU analysis

33

Methods of enhancing

learning quality

Cost

(1-5; 1=high

cost)

Evidence on

impact

(1–5; 1=low)

Time to

impact

(months)

EIU

impact

rating

Levels of support

and degree of

student–teacher

interaction

Mentoring 3 4 0 months

Peer tutoring 5 4 5 months

Extension of

school times

3 3 2 months

Parental

engagement

3 3 3 months

One-to-one

tuition

2 4 5 months

Reducing

classroom sizes

2 3 3 months

Small group

tuitions

3 2 4 months

Learning styles

and approaches

Collaborative

learning

5 4 5 months

Individualised

instruction

5 3 3 months

Homework 5 2 2 months

Tailored learning

styles

5 2 2 months

Feedback 5 3 8 months

Within-class

attainment

grouping

5 2 3 months

Complementary

learning tools

and activities

Digital

technology

3 4 4 months

Arts

participation

4 3 2 months

Sports

participation

3 2 2 months

EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/teaching-learning-toolkit/

EIU analysis places the following weights on each of the criteria to assess the overall impact of alternative means of enhancing the quality of

education: cost = 30% weight; evidence on impact = 50% weight; time to impact = 20% weight

18

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

The role of the internet in

enhancing the quality of education

While there are a number of ways to enhance

the quality of education, the use of digital

learning tools through access to the internet

is gaining particular traction due to both its

impact on educational outcomes and its longer-

term impacts on students by providing them

with high-in-demand digital skills that open

doors to higher education and a wider range

of career options. These digital skills also allow

communities to develop by enabling new and

more eective approaches to doing business,

providing access to a greater online market.

The potential uses of the internet in the context

of education are wide-ranging. From the

perspective of students, it puts access to learning

material and resources at the tips of their

fingers—including not only the best prepared

content, but also access to live or pre-recorded

lessons led by the best teachers from around

the world. The internet serves as a repository of

knowledge that is not restricted by geography

and is available to anyone with connectivity. It

allows the traditional schooling model to evolve,

facilitating access to a wealth of educational

material. Meanwhile, access to textbooks

is far more restrictive—an evaluation of the

curriculum in Kenya, for example, concluded

that English textbooks benefit primarily elite and

academically stronger students. The internet

has the potential to facilitate the availability

of resources in local languages and could

produce achievement gains on a wider scale.

34

Increased school connectivity and access to

digital learning tools also provide numerous

resources for teachers to enable them to

both develop professionally and teach more

eectively. In developing countries, higher

internet penetration provides an opportunity to

develop the skills of teachers in a cost-eective

manner, which is particularly crucial when there

is a shortage of qualified teachers. As access

to education across the world grows, there is a

risk that the teaching profession could become

unmanageable with growing class sizes—in this

context, digital technologies can also support

teachers by providing them with additional tools

and, through blended learning approaches,

freeing time for them to focus on teaching

rather than on administration. Furthermore,

internet access enables teachers to focus

attention where it is needed by providing real-

time information on student performance.

35

Deloitte (2014), “Value of connectivity: Economic and social benefits of expanding internet access”. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/

Deloitte/ie/Documents/TechnologyMediaCommunications/2014_uk_tmt_value_of_connectivity_deloitte_ireland.pdf

Internet Society (2017), “Internet Access and Education: Key considerations for policy makers”.

https://www.internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2017/internet-access-and-education/

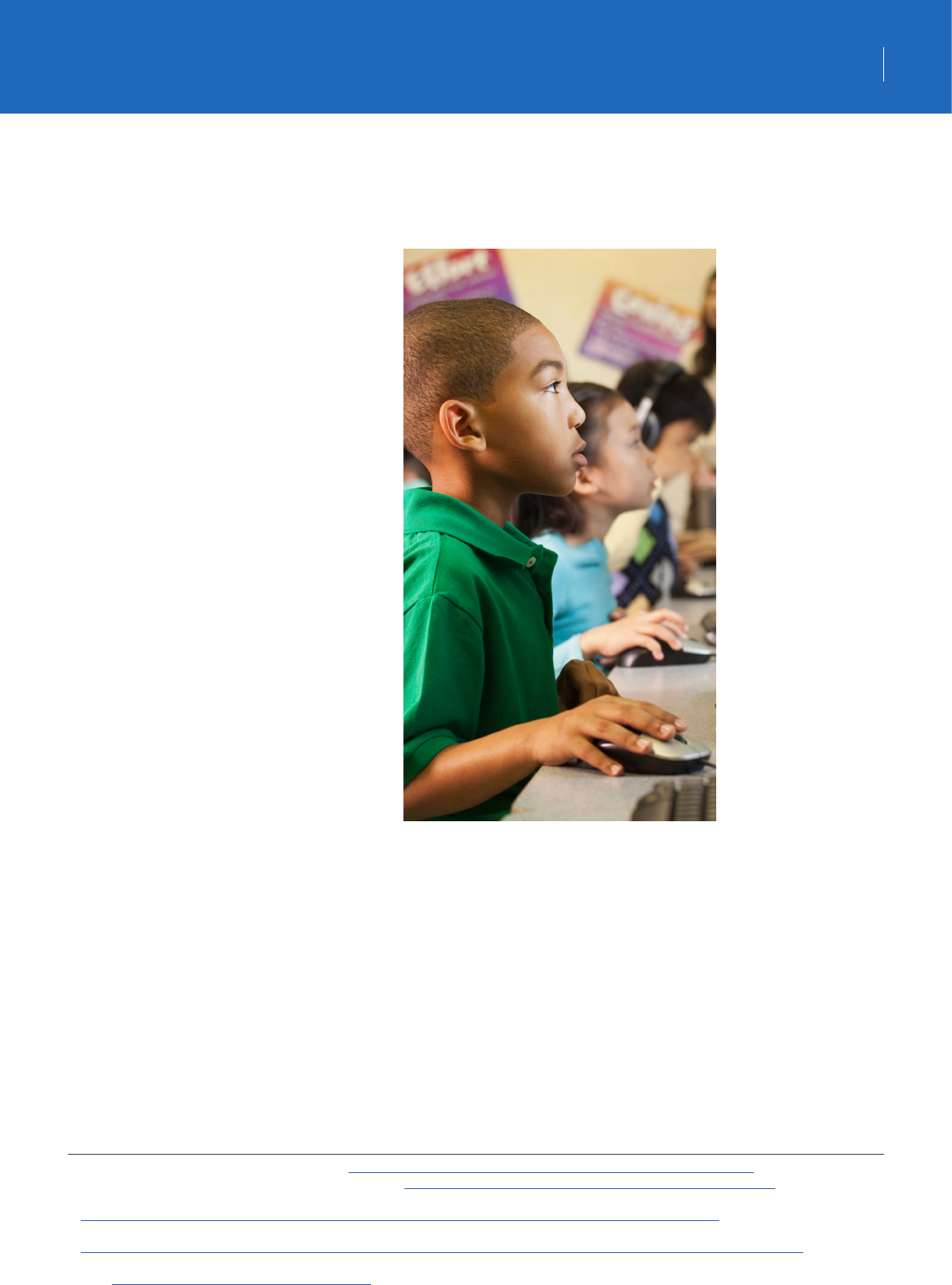

We need to address the sharp

increase in heterogeneity in student

preparation for school caused

by recent expansions in access.

Technology has several comparative

advantages to complement teacher-

led instruction on this front.

Alejandro Ganimian, Assistant Professor

at New York University

© UNICEF/Panjwani

19

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Finally, in addition to the use of the internet

by students and teachers, increased school

connectivity provides policymakers with

better tools to monitor and evaluate

programmes. This enables more eective

and agile policymaking to contribute to the

overall quality of education across a nation.

Digital tools can, for example, enable more

sophisticated Education Management

Information Systems (EMIS), which can be

used to disseminate to the government

high-quality and timely data on educational

inputs, outputs and outcomes.

36

Professional

development

courses

Reduced

burden of

managing

large class

sizes

Access to

real-time

information

on student

performance

Real-time

access to

learning

outcomes

Real-time

monitoring

of policy

implementation

Engagement

of external

players in

education

Connecting students, teachers and policymakers

The role of school connectivity in education

School internet

connectivity

Teachers

Government

policy

Students

Facilitated

interaction

Access to

textbooks

and content

in desired

languages

On-demand

classes and

vocational

courses

Development

of digital

skills

Facilitated

interaction

Connecting students, teachers and policymakers

The role of school connectivity in education

Source: EIU research

Without connectivity, the learning

crisis is often hidden. The focus

is on getting more children

into schools, but this doesn’t

mean that they are learning.

Through better connectivity,

we can get data on a much more

frequent basis and improve

overall learning outcomes.

Radhika Iyengar, Education Sector Director

at Columbia University

UNICEF (2020), “EMIS to monitor ICT in education”. https://iite.unesco.org/highlights/emis-and-ict-in-education/

20

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

COVID-19 and the widening

role of the internet

Around April 2020, as part of measures to

curb the spread of COVID-19, more than

190 countries instituted nationwide school

closures putting, in the blink of an eye, over

1.6 billion students out of school-based

education.

37

From schools transitioning to

online classes, to oce workers now working

from home, all of sudden the internet—

and specifically, access to the internet at

home—became the solution to the threat of

complete social disconnection and economic

standstill posed by the global lockdown. In

fact, because of access to connectivity in the

home, it is estimated that at least 100 million

schoolchildren across the world were able to

continue learning. As a comparison, with the

levels of access available in 2000, a similar

pandemic would have allowed less than 1.3

million children to remain connected.

38

Yet,

while progress has been made with 100 million

schoolchildren able to continue to learn during

the current pandemic, this represents only

one in 16 school-aged children—over 1.3

billion do not have access to the internet in

their homes.

39

Although it is clear that access to the internet

at home remains inadequate in many regions,

the pandemic has accelerated a transition in

the model of education towards increased

integration of digital technologies. Many

believe that it oers the opportunity to “build

back better” by re-imagining education and

how it is delivered.

40

It has made us realise

that: (a) it is not only access to the internet

through schools, but also access at home that

is important; and (b) how late we already are in

embracing and leveraging the full potential of

these technologies. In the world of education,

the pandemic highlighted the variety of roles

schools can play if teachers and students are

connected to the internet, from continuing to

provide regular classes to oering physical and

mental health guidance and, perhaps most

importantly, reducing the impact of isolation.

Educators also discovered a silver lining in the

creative approaches they could take towards

schooling. They have embraced novel ways of

interactive learning and have ultimately led the

way in enriching life experiences and fostering

meaningful cultural exchanges while teaching

from remote locations. For many educators, it

would have been better if they were already

connected and trained with internet tools.

UNICEF (2020), “How many children and young people have internet access at home?”. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/

publications/UNICEF/How-many-children-and-young-people-have-internet-access-at-home-2020_v2final.pdf

Rastogi, V. et al (2020), “A $2 Trillion Plan to Bring Two Billion More People into the Digital Age”. https://www.bcg.com/en-in/publications/2020/plan-

to-bring-high-speed-internet-access-to-two-billion-people

UNICEF “Two thirds of the world’s schoolage children have no internet access at home new UNICEFITU report says”

https://wwwuniceforg/pressreleases/twothirdsworldsschoolagechildrenhavenointernetaccesshomenewunicefitu

Iyengar, R. (2020), “Education as the path to a sustainable recovery from COVID-19”, PROSPECTS volume 49, pages77–80(2020).

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11125-020-09488-9

Things have changed quite a bit with COVID-19. We

now realise that communities play a big role beyond

schools. The idea that children only learn in schools

is an old model and we’re now moving beyond

this idea. Technology and the internet enable an

interface between the school and the community.”

Radhika Iyengar, Education Sector

Director at Columbia University

© UNICEF/Everett

21

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

While internet connectivity has enabled the

continuity of learning for some, the transition

has not been seamless in all contexts, and

access to the internet to respond to the

impacts of the pandemic has not been

an option for everyone.

41

A World Bank

report concluded that learning losses as a

result of school closures could reduce the

incomes across all impacted students by a

total of US$10 trillion over their lifetimes,

with these costs falling disproportionately

on disadvantaged students

42

—this could

translate into an income loss of approximately

3% per student.

43

There is no doubt that

the digital divide is becoming all the more

evident and is perpetuating inequalities.

While the focus of this research is on

connectivity to the internet and access to

digital tools through schools, the importance

of internet connectivity for schoolchildren

regardless of their physical location—be

it a school, home, the public library, or

anywhere else—is now clearer than ever.

Regardless of the shift in education models

initiated by the pandemic and the realisation

of the need for internet connectivity in

general, the role of school connectivity and

access to digital learning remains an important

area of discussion for a number of reasons:

• Many children are returning to school.

Many of the school closures instigated

by governments were short-term—by

September 2020, only 50% of learners

were still aected and this has continued

to decline.

44

As students return to school,

having access to the internet and digital

learning tools in their schools remains

important. If anything, the temporary

school closures have changed perceptions

on digital technologies in education and

have highlighted the benefits of the use

of online tools in supporting learning, and

not just replacing traditional methods of

teaching. Indeed, the need to provide digital

connectivity beyond schools is also now

recognised, but without diminishing the role

of school connectivity.

Unwin, T. et al (2020), “Education for the most marginalised post-COVID-19: Guidance for governments on the use of digital technologies in

education”, EdTech Hub. https://edtechhub.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Education-for-the-most-marginalised-Report-Act-2-v8.pdf

World Bank (2020), “COVID-19 Could Lead to Permanent Loss in Learning and Trillions of Dollars in Lost Earnings”. https://www.worldbank.org/en/

news/press-release/2020/06/18/covid-19-could-lead-to-permanent-loss-in-learning-and-trillions-of-dollars-in-lost-earnings

Hanushek, E. and Woessmann, L. (2020), “The Economic Impacts of Learning Losses”, OECD.

https://www.oecd.org/education/The-economic-impacts-of-coronavirus-covid-19-learning-losses.pdf

Unwin, T. et al (2020), “Education for the most marginalised post-COVID-19: Guidance for governments on the use of digital technologies in

education”, EdTech Hub. https://edtechhub.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Education-for-the-most-marginalised-Report-Act-2-v8.pdf

I don’t think physical schools will be going away

anytime soon. Yes, some families might shift to a

new hybrid form of education. But these are going to

be the elites and those that have the ability to do so.

So students that do show up in schools are likely

to be those with more limited resources, making

school connectivity all the more important.

Macke Raymond, Director of CREDO at Stanford University

© UNICEF/Panjwani

22

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Nobody gets a telecommunication

connection for its own sake. You

get it for the things that you can

do with it. Demonstrating the

impact of what you can do with

it provides the missing link.

When you say that connectivity

improves health or education

outcomes, that is where you

can start to build solutions.

Christopher Yoo, Director at the Center for

Technology, Innovation and Competition at the

University of Pennsylvania

USAID (2018), “Better connectivity, Better programs: How to implement a broadband demand aggregation program”.

https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/15396/Better_Connectivity_Better_Programs_April2018.pdf

• Enabling connectivity for communities.

School connectivity is important not only

for the benefits it provides to learners,

but also for enabling wider connectivity

for communities. By creating demand for

telecoms services, school connectivity

can make it commercially viable for the

infrastructure to be developed and can

also increase service quality and reduce

costs—a concept known as demand

aggregation.

45

• Obtaining government funding

for infrastructure development.

Demonstrating the impact of developing

telecoms infrastructure is a prerequisite for

obtaining public sector financing. School

connectivity provides this impact. However,

education budgets are already overstretched.

Hence, finding financing mechanisms

that engage the private sector and other

government entities will be crucial.

Connecting schools can serve to close both

the educational divide and the digital divide.

Schools are not only places where children

learn, but also often community hubs—places

where people vote, where public resources

(like vaccines) are administered, and where

people shelter during natural disasters, among

other community uses. Providing connectivity

to a school is a way to empower children with

access to world-class digital content, but it is

also a means to enable local entrepreneurship,

provide access to online banking, improve

information channels during emergencies or

pandemics, and open doors for employment

through digital platforms and the gig economy.

It is through this lens that school connectivity

becomes an important focus for achieving

broader social and economic goals in

communities on a global scale.

The remainder of this report focuses on the

role of the internet in the context of schools,

and the impacts of this connectivity not only

for students, but also for the rest of society

and wider economies.

23

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Internet connectivity:

A basic human right

Access to the internet is increasingly becoming

a basic human right. The United Nations

Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),

adopted by 140 countries in 1989, established

a legal framework for the basic human rights

of every child to “grow, learn, play, develop and

flourish with dignity”.

46

While the CRC pre-

dates the widespread adoption of the internet,

the challenges, threats and opportunities

posed by digital technologies in achieving its

aims and upholding the rights of children are

becoming increasingly evident. As highlighted

by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on

freedom of opinion and expression: “access

to the internet is not only essential to enjoy

the right to freedom of expression, but also

other rights, such as the right to education,

3. Connecting schools, bridging gaps

the right to freedom of association and

assembly, the right to full participation in

social, cultural and political life and the right

to social and economic development.”

47

As a society, we have not yet achieved universal

and aordable access to the internet for all.

While the global internet penetration rate

has increased substantially from 17% in 2005,

it remains only just over 50%.

48

There are

also large disparities between, and within,

countries across rural and urban populations.

In developed countries, 87% of the urban

population has access to the internet. In the

least-developed countries, the figure stands

at only 25%—and for the rural population,

access is even lower at 10%.

49

Regionally,

Europe has the highest internet usage rates,

while Africa has by far the lowest.

50

UNICEF, Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/what-is-the-convention

United Nations General Assembly, 10 August 2011. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Opinion/A.66.290.pdf

International Telecommunication Union (2020), “Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2020”.

https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2020.pdf

Ibid.

Ibid.

© UNICEF/Frank Dejongh

24

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Disparities in internet access

The share of individuals using the internet across regions (%)

0

1

00

75

50

25

World Africa Arab States

Asia & Pacific

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

Europe The Americas

2005 2010 2015 2020

Disparities in internet access

The share of individuals using the internet across regions (%)

Source: : International Telecommunication Union 2020

51

Inequalities in school connectivity

The disparities in internet access across

countries at the national level are also reflected

in disparities in school connectivity. Lack of

access to the internet hampers access to

education and denies the “right to education”,

further widening educational gaps between

the privileged and the deprived, or those

with internet access and those without.

52

The inequality that a lack of school connectivity

and access to digital learning creates begins

from childhood is perpetuated from that point

on—in many ways, as reflected by Henrietta

Fore, UNICEF Executive Director, “lack of

internet access is costing the next generation

their futures.”

53

Looking first at the opportunities,

or lack thereof, for children therefore forms

a good starting point to evaluate the broader

impacts of internet disconnectivity.

International Telecommunication Union. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx

Bajpai, R. (2020), “Right to Education & Emergence of a Digital Divide in Digital India”.

http://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/right-to-education-emergence-of-a-digital-divide-in-digital-india/

UNICEF (2020), “Two thirds of the world’s school-age children have no internet access at home, new UNICEF-ITU report says”.

https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/two-thirds-worlds-school-age-children-have-no-internet-access-home-new-unicef-itu

25

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Enhancing the quality of education

The relationship between school internet connectivity and education quality

Source: World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Index (2017), World Bank Human Capital Index (2017)

UNICEF (2020), “How many children and young people have internet access at home?”.

https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-and-young-people-internet-access-at-home-during-covid19/

Globally, it is estimated that 2.2 billion children

and young people under the age of 25—or

two-thirds of this age group—do not have

access to the internet.

54

Dierences in school

internet access also give rise to dierences

in the quality of education within and across

countries, and threaten to widen the gap

in outcomes for students with and without

access. At the national level, low levels of school

connectivity are associated with poor quality

of education, with higher-income countries

displaying both greater connectivity and higher

quality of education (see chart below). Access

to the internet in schools holds the potential

to equalise opportunities at an early age which

can then proliferate throughout childhood and

adulthood—bringing not only benefits at an

individual level but to society in its entirety.

Enhancing the quality of education

The relationship between school internet connectivity and education quality

Low income

Education quality (Learning-adjusted years of schooling)

School internet connectivity (Index score 1-7; 7 = best)

Middle income High income

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5 5.0 5.5 6.0 6.5

26

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Leveling the playing field

As digital learning becomes increasingly

embedded within education curricula, the

cost of a lack of school connectivity will grow.

The gap in educational outcomes between

schoolchildren with and without access to the

internet at school could widen more than ever

before. While the disparity in school connectivity

creates a massive threat of economic and social

divergence, it also highlights the significant

opportunity to level the playing field for all

children regardless of geography or income

levels through eorts to improve access. A

study by Deloitte found that internet access

could be extended to an additional 640 million

children around the world, bringing with it the

benefits of access to resources, improved quality

of education, better learning outcomes and

enhanced employability.

55

Studies have highlighted the significant

potential of school connectivity to bring

direct benefits to individual students. The

chain of benefits begins from improved

learning outcomes for children, driven by

improved access to learning resources and an

enhanced quality of education. Combined with

improved digital skills, the improved outcomes

for students also expand opportunities

for further education. Beyond education,

this then opens up doors to new career

pathways, bringing higher income levels and

an overall improvement in quality of life.

Individual-level benefits from school connectivity and access to digital learning

Pathway from improved connectivity to a better quality of life

Source: EIU

Deloitte (2014), “Value of connectivity: Economic and social benefits of expanding internet access”. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/

Deloitte/ie/Documents/TechnologyMediaCommunications/2014_uk_tmt_value_of_connectivity_deloitte_ireland.pdf

Individual-level benefits from school connectivity

Pathway from improved connectivity to a better quality of life

Improved income

Improved employability

Improved education performance

Improved opportunities in

secondary/tertiary education

Improved quality

of education

Improved access

to resources

Improved digital

literacy skills

Improved

quality of

life

Improved school internet connectivity

27

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

If a student is studying about a particular topic in science, the

amount of information they can get from an illustration in

a textbook is very different to seeing a live simulation from

digital content obtained through the internet - the ability to

learn, and also to retain the information, is enhanced.

Eric Kimenyi, Teacher Training Program Manager at the

African Institute of Mathematical Sciences

• Improving learning outcomes. Internet

connectivity has been rapidly evolving from

a nice-to-have to an essential element of

education. From putting access to knowledge

and information at our fingertips, to enabling

new ways of interactive learning, the benefits

to learners are manifold.

56

Through improving the quality of education,

school connectivity has been shown to

have positive impacts on learning outcomes

for children. Michigan State University

conducted a 2018 study on the impact of

internet access on student learning in Peru.

57

Using variation in the timing of internet

installation across schools in the country,

internet access was found to lead to initial

modest improvements in maths scores,

but these impacts were found to grow

significantly over time as schools adapted

by hiring teachers with computer training.

Johnston and Ksoll (2017) also evaluated a

programme that broadcast live instruction

via satellite to rural primary school students

in Ghana. The intervention improved the

numeracy scores of students in grades 2

through 4, as well as certain foundational

literacy tasks,

58

driven by improvements in

the quality of education.

UNICEF (2017), “Access to the internet and digital literacy”. Discussion Paper Series: Children’s Rights and Business in a Digital World.

https://www.unicef.org/csr/css/UNICEF_CRB_Digital_World_Series_ACCESS.pdf

Kho, K. et al (2018), “Impact of Internet Access on Student Learning in Peruvian Schools”. Michigan State University, International Food Policy

Research Institute. http://econ.msu.edu/repec/wp/Draft04-08-18.pdf

See Ganimian, A. et al. (2020), “Realising the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all”. The Brookings Institution, Center for

Universal Education. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/edtech_playbook_full_v2.pdf

28

Connecting learners

Narrowing the educational divide

© The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

The quality enhancement from school

connectivity and digital learning which

results in improved learning outcomes comes

through a number of channels:

- Access to learning resources. First, the

internet provides access to unlimited

learning resources where previously

students were restricted to the knowledge

of their teachers and the information

contained within textbooks. Students in

remote rural villages are suddenly able

to access not only static content, but also

on-demand or live content, produced and

delivered by the world’s leading academics

and educationalists, thus removing

geographical and income barriers in access

to quality education. Massively Open

Online Courses (MOOCs) are another form

of digital learning that are also becoming

increasingly popular as a means of

supplementing traditional learning provided

by schools and other educational settings,

oering students a holistic education.

59

These new channels of learning opened up

by the internet oer significant potential to

improve the educational outcomes for those

who are able to obtain access.

- Dynamic adaptation of curricula. The

internet can also be used as a tool for

learning beyond the provision of learning

resources. The ability to adapt learning

based on the specific needs of the child

and in response to their abilities through

dynamic feedback loops both significantly

reduces the burden on teachers to tailor

content to meet the needs of a wide range

of abilities, and provides better learning

outcomes for children. Recent research

on the use of technology in education in

India has found that, for students with

low performance levels, the ability to

receive personalised education based on

individual ability had a significant impact

on performance in maths tests.

60

Selwyn, N. (2014), “The Internet and Education”. https://www.bbvaopenmind.com/en/articles/the-internet-and-education/

De Barros, A. and Ganimian, A. (2021), “Which Students Benefit from Personalized Learning? Experimental Evidence from a Math Software in Public