A T W E N T I E T H

-

CENTURY

COSMOS

THE COLLEGE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

JOHN W. BOYER

T H E

NEW PLAN

A N D T H E

ORIGINS OF

GENERAL

EDUCATION

AT CHICAG O

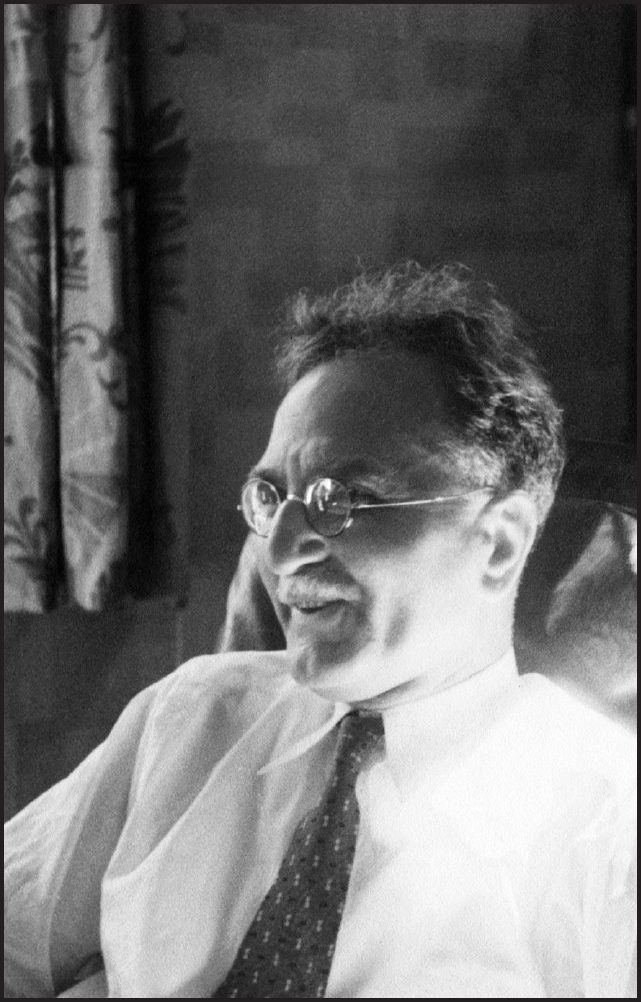

Ferdinand Schevill, undated photograph by Norman F. Maclean

he condition of the liberal arts at elite colleges has been

highly visible in public discussions in the last several

years, inspiring commentary in the press and on college

campuses across the country. Some of this debate has

come in response to issues of academic freedom, as colleges face criticism

for failing to defend the rights of faculty to teach freely without political

interference, as well as coercive pressures from outside the academy or

from various interest groups within the campuses themselves (including,

unfortunately, student groups seeking to pressure the faculty to teach or

not teach in certain ways). Other voices have addressed the perceived

failure of institutions to develop coherent and thoughtful curricular pro-

grams that enable students to engage the full sweep of liberal-arts

disciplines. Among the latter are analysts who argue that elite institutions,

under the sway of educational neoliberalism, have reduced the value of

the liberal arts to their economic utility. Where higher education once

sought the formation of character and intellectual autonomy, it has now

conformed to the language and values of the marketplace. is, the

A TWENTIETH-

CENTURY COSMOS

The New Plan and the Origins of

General Education at Chicago

INTRODUCTION

This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on

October 31, 2006. John W. Boyer is the Martin A. Ryerson Distinguished Service Professor

in History and the College, and Dean of the College.

T

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 2

argument goes, is perilous to the work of self-discovery, especially to the

study of the humanities, which are being eclipsed by more lucrative

majors in the STEM elds and economics. is is a potent and in some

ways arresting argument. Yet it recapitulates many of the charges of edu-

cational corruption that have surfaced regularly about American higher

education since the early twentieth century. It supposes an institution

whose curriculum and mission are shapelessly adapted to new fads, lack-

ing the legitimacy of a campus culture that is itself suused with scholarly

values.

Fortunately, that institution is not the University of Chicago. One of

the dening themes of our 125-year history has been thoughtful curricu-

lar innovation by the faculty, rooted in the values of interdisciplinary

thought, rigorous meritocracy, and intellectual analysis. ese values lie

at the heart of the Core, which introduces every student, regardless of

major, to the practices of humanistic reection as a basis for further study

and has been able to accommodate many challenges since the 1930s.

e College’s Core curriculum has been one the most eective instru-

ments for our University to sustain our collective memory work. A

curriculum is more than a set of formal prescriptions and requirements.

It is a statement of basic values and a way by which the faculty can assert

what is educationally important and what is not, and how it wishes to

organize its own work, based on past traditions and past experience. e

curriculum also comes to constitute the cognitive framework through

which our alumni remember their intellectual accomplishments while

on campus, giving them a special sense of having lived and been trans-

formed in a special place. And our curriculum is a public commitment

and a public armation that we will educate our students for the kind

of future—humane, tolerant, enlightened—that all of us esteem and

hope will always come to pass.

JOHN W. BOYER3

Since the early 1930s the College’s curriculum has been most noted

for its tradition of general education. is year—2017–18—is the nine-

tieth anniversary of the formulation of the rst plan to develop a program

of general education at the University of Chicago, a plan that led three

years later to the launching of the rst Core courses in the College in the

autumn quarter of 1931. It is thus an appropriate moment to pause and

consider what these courses were, how they came about, how they embed-

ded themselves in our institutional consciousness, and how they managed

to sustain themselves or their ospring in the decades that followed. A

few years ago Arnold Rampersad of Stanford University, who once taught

at Columbia University, observed that the Core curricula of universities

like Columbia and Chicago were like the federal interstate highway

system—you could never build them the same way again, but since they

exist, you can take care of them, keep them functioning, and help them

to achieve the educational objectives that are rather unique to such special

systems of liberal education.

1

In this essay I want to explore how that

“highway system” came to be built, who built it, why they built it, and

what we should do with it now.

1. See Charles McGrath, “What Every Student Should Know,” New York Times,

January 8, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/08/education/edlife/what-

every-student-should-know.html. I issued an earlier version of this essay in

October 2006. e present version, completed in July 2017, oers a signicant

revision which takes the story down to the present. I am extremely grateful to

Daniel Koehler and Michael Jones for their assistance. I am also grateful to Leon

Botstein, Terry N. Clark, Martin Feder, Hanna Holborn Gray, Paul H. Jordan,

Ralph Lerner, Joel Snyder, and William Veeder for answering questions about

specic individuals or events that are discussed in this essay.

Chauncey S. Boucher, undated photograph by Norman F. Maclean

JOHN W. BOYER5

THE NEW PLAN AND

THE CREATION OF A GENERAL-

EDUCATION PROGRAM

ur traditions of general education date back to the late

1920s, when a group of colleagues at Chicago decided

to revolutionize the world of higher education by creat-

ing what was called the New Plan, a bold attempt to

synthesize broad elds of knowledge in an explicitly interdisciplinary

framework for rst- and second-year students in the College. e New

Plan was our rst Core curriculum, and the current curriculum, passed

in 1998, owes much to the spirit and practices of the New Plan.

e New Plan was the brain child of Dean of the College Chauncey

S. Boucher who was rst appointed to the deanship in 1926. Briey,

during the late 1920s Boucher came to be dissatised both with the level

of intellectual accomplishment of undergraduates at Chicago and with

the somewhat lackadaisical way in which the University treated under-

graduate education. Even before Robert Maynard Hutchins assumed the

presidency in the summer of 1929 Boucher had conducted a lobbying

campaign to create a new curriculum of general-education courses based

on a comprehensive examination system and a new approach to under-

graduate education.

2

Boucher argued:

2. See Chauncey S. Boucher, “Suggestions for a Reorganization of Our Work

in the Colleges, and a Restatement of Our Requirements for the Bachelor’s

Degree,” December 1927, Dean of the College Records, 1923–1958, box 27,

folder 6; and “Report of the Senate Committee on the Undergraduate Col-

leges,” May 7, 1928, ibid., folder 7, Special Collections Research Center,

University of Chicago Joseph Regenstein Library. Unless otherwise noted, all

archival documents cited in this essay are located in the center.

O

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 6

A trick of fate put me into the Dean’s oce where I soon began to

get a much broader and entirely new perspective. At rst I thought

that a dean must necessarily spend most of his time and eorts

quibbling with students over one or another of the numerous book-

keeping regulations for the attainment of a degree, and on

disciplinary problems—in fact I thought that a dean must be pri-

marily a petty police ocer, spending his time catching and

torturing ies. I had no stomach for such activities any longer than

was necessary to allow the President’s oce time enough to enlist

a man to take the place. Very soon, however, I learned that Presi-

dent Mason and Vice President Woodward were anxious to do

something really signicant with the Colleges and were ready to

entertain any constructive suggestions which the Dean might have

to oer. I then began in earnest to study the biggest problems of

college education, particularly our own problems, and, by spend-

ing as little time as possible on the petty aairs of the oce, I soon

became deeply interested in the major problem.

3

Boucher’s real ambition, articulated in many position papers that he

wrote between 1927 and 1930, was to begin to recruit more motivated

and academically gifted students to the Colleges and then to put them

in a more coherent and rigorous instructional program that was not

controlled by the departments and that would be protected by an inde-

pendent Oce of the Examiner. He sought to construct a completely new

system of general education for all areas of the arts and sciences at the

3. Boucher, “Suggestions for a Reorganization of Our Work in the Colleges,”

53–54. Boucher gave this long appeal to Max Mason in January 1928 and sent

it to his colleagues in the University Senate on March 12, 1928.

7

University of Chicago, and he had to do so in a way that the inuential

factions of senior natural- and social-science faculty at Chicago would

accept, if not actively embrace.

Having been inspired by a talk that President Max Mason gave to the

Institute for Administrative Oces of Institutions of Higher Education

in July 1927, Boucher began to survey the state of collegiate education

nationally and to consult with experts who would speak with him:

I read more widely whatever literature would give me the current

practice and progressive thought of men in other institutions; I

talked with about thirty individuals in various departments and

schools of the University of Chicago; in January 1928 I made a

trip to learn rst hand what is going on at Princeton, Columbia,

and Harvard. I talked with many of the leading constructive

thinkers at each of these institutions. My object was rst of all to

see what features of the practice at each of these institutions could

be adapted to our conditions; secondly, I was anxious, if given any

encouragement, to tell the main features of the plan on which I

was to work, in order to get the constructive and corrective sug-

gestion of these men whose training and experiences would make

their opinions valuable.

4

4. Boucher, “Suggestions for a Reorganization of Our Work in the Colleges,”

51–52.

Boucher’s visit to Columbia doubtlessly led him to investigate the

Contemporary Civilization course rst launched in 1919.

5

But it would

be a mistake to think that Boucher was trying to copy such models, for

the political and intellectual challenge that he faced at Chicago was much

more radical than anything that the Columbia humanists like John J.

Coss and Harry J. Carman had faced in the 1920s in creating their new

history course. e relative prestige of the senior social, biological, and

physical scientists among the arts and science faculty at Chicago at the

time meant that Boucher had to attract their support and design a cur-

riculum with a substantial investment in the natural and social sciences,

along with the humanities. A critical turning point seems to have been

his six-hour visit in New York City in late January 1928 with William S.

Learned, a senior sta member at the Carnegie Foundation for the

Advancement of Teaching and a remarkable interwar critic of secondary

and tertiary levels of education in America. In 1927 Learned had pub-

lished a tough critique of the state of American higher education in which

he denounced “the bane of the average” that aicted American colleges

and universities. Looking over the landscape of college and university

programs, Learned saw incoherence, lack of rigor, a jumble of course

credits and grading practices that had no rational purpose or aim, and,

most seriously, a complete distain for “the intellectual vision, energy, and

5. See John J. Coss, “A Report of the Columbia Experiment with the Course on

Contemporary Civilization,” in e Junior College Curriculum, ed. William S.

Gray (Chicago, 1929), 133–46; Justus Buchler, “Reconstruction in the Liberal

Arts,” in A History of Columbia College on Morningside, ed. Dwight C. Miner

(New York, 1954), 48–135; Gary E. Miller, e Meaning of General Education:

e Emergence of a Curriculum Paradigm (New York, 1988), 35–41; and Timo-

thy P. Cross, An Oasis of Order: e Core Curriculum at Columbia College (New

York, 1995).

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 8

JOHN W. BOYER9

enthusiasm of young minds.”

6

Boucher was much taken by Learned’s

proposals for enhancing curricular rigor and his disdain for course credits,

and Learned encouraged him to pursue a set of fundamental, transdisci-

plinary structural reforms.

7

If any single outside inuence shaped the

creation of Chicago’s rst Core curriculum, it was the work of empiricists

like William Learned and his colleagues at the Carnegie Foundation.

8

A month later Boucher constituted and chaired a faculty committee

that formulated his reform program and presented it to the University

6. William S. Learned, e Quality of the Educational Process in America and in

Europe (New York, 1927), 42–48, 98–125. Learned was chiey responsible for

organizing the famous Pennsylvania Study which examined learning outcomes

for large numbers of high school and college students in that state between 1928

and 1932 on the basis of systematic assessment testing. He was also the architect

of the rst Graduate Record Examination, created in 1937 on a trial basis with

the cooperation of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia.

7. Boucher reported that he considered Learned “to be the one man in the coun-

try, if there is any such one man, best prepared and best qualied to give a critical

judgment on any such plan as the one proposed.” After going over his plan with

Learned, he was pleased to report that Learned “sincerely hoped the University

of Chicago would adopt the plan and carry it into successful operation in the

immediate future,…because if the University of Chicago were to inaugurate

such a system of work and requirements, it would be more signicant in its

eects on both secondary and college education in this country than if it were

done by any other institution.” Boucher, “Suggestions for a Reorganization of

Our Work in the Colleges,” 52–53. On Learned’s opposition to course-based

credit and grading, see Paul F. Douglass, Teaching for Self Education—As a Life

Goal (New York, 1960), 82–89. See also Ellen Condlie Lagemann, Private

Power for the Public Good: A History of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advance-

ment of Teaching (Middletown, Conn., 1983), 101–7.

8. In his 1932 Inglis Lecture at Harvard, Learned spoke approvingly of

“the recent revolution at the University of Chicago,” signied by its use of new

comprehensive examinations. See Realism in American Education (Cambridge,

Mass., 1932), 27–28.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 10

Senate on May 7, 1928. e committee was dominated by a centrist

group of scholars who were sympathetic to the cause of undergraduate

education. ey included Julius Stieglitz, Anton Carlson, Leon Marshall,

and, perhaps most notably, Charles Judd of the Department of Educa-

tion. Boucher’s plan called for a set of bold changes: the establishment

of a junior-college program that would have its own curricular structure

distinct from the control of the departments but taught by the regular

research faculty; the revision of the curriculum for the rst two years of

the undergraduate work, which would replace ad hoc departmental oer-

ings with broad survey courses based on research ndings of the faculty

(an idea that built on an earlier experiment in the natural sciences in the

mid-1920s); the use of ve general-education competency examinations

to assess and evaluate student progress, which students might take when-

ever they felt ready; additional new subject area courses designed to meet

student interest in early specialization, particularly in the natural sciences;

and the abolition of mandatory quarterly course examinations.

9

Nor did

Boucher restrict himself to intrepid curricular changes, for his plan also

presumed that several million new dollars would be invested in new resi-

dence halls, in additional endowment to pay for the upkeep of these halls,

and in the construction of instructional facilities and the expansion of

undergraduate library resources as well.

10

Finally, although he insisted on

9. “Report of the Senate Committee on the Undergraduate Colleges (presented

to the University Senate, May 7, 1928),” Presidents’ Papers, 1925–1945, box

19. is report contains as well a “Supplementary Statement” by Boucher. e

May 1928 report was based on a long document that Boucher prepared in

December 1927, “Suggestions for a Reorganization of Our Work in the Col-

leges, and a Restatement of Our Requirements for the Bachelor’s Degree.”

10. “Suggestions for a Reorganization of Our Work,” 53–58; as well as “Bait,

cut by C. S. Boucher,” January 7, 1930, 18–19, Presidents’ Papers, 1925–1945,

box 19. In mid-December 1928 the university announced a $2 million gift from

JOHN W. BOYER11

new resources for the College, Boucher wished to keep most of the actual

instruction on the main quadrangles to avoid creating an undergraduate

ghetto. For those who sought to marginalize undergraduate education at

the University of Chicago, these proposals, taken in their entirety, were

a declaration of war.

Boucher draped his plan in the aura of the research university with

the research-based content of courses; the intellectual individualism,

stamina, and autonomy required of undergraduates; and the regime of

“scientic” testing that would evaluate student achievement. Among his

original recommendations in May 1928 was the idea that the College

should make it possible “to save time for the better students, who are able

to develop themselves both faster and more thoroughly than the average

student, by awarding the [bachelor’s] degree on the basis of demonstrated

accomplishment, rather than on a required number of course credits, and

thus break up the lock-step system.”

11

Boucher was convinced that he

had designed a system that would eliminate most of the glaring ills that

Learned found evident in American higher education. But he also hoped

that, in attracting more intellectually independent students who would

merit the respect and admiration of the regular departmental faculties,

he would be able to rescue the undergraduate program at Chicago from

its politically marginal status.

Boucher’s strategy for a curricular revolution stumbled in early May

1928 when President Max Mason unexpectedly resigned to become

Julius Rosenwald (matched by a $3 million commitment from the university)

for the construction of new undergraduate dormitories for men and women.

“Proposal for a Dormitory Development on a 40% Gift and 60% Investment

Basis,” [1928], Records of the Department of Buildings and Grounds, 1892–

1932, box 12.

11. “Supplementary Statement,” May 7, 1928, 1, 11.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 12

director of the Natural Sciences Division at the Rockefeller Foundation,

with the informal understanding that he would then become president

of the foundation within a year or two. e resulting power vacuum in

the summer of 1928 put Boucher’s scheme in limbo. Attempts to imple-

ment the reforms in a piecemeal fashion in later 1928 inevitably stalled,

and Boucher felt isolated and unsupported, beset by powerful forces

intent on thwarting his plans to strengthen undergraduate education.

12

Still, Boucher was convinced that a more challenging and more imagi-

native curriculum would attract intellectually stronger students to

Chicago, and he was prepared to gamble that the University could nd

ways to enhance student quality and commitment. Even though Chicago

might lose a signicant share of its weaker and less committed students,

they would soon be replaced by

a better type of student; the young people of the United States are

keen enough to recognize the best to be had in education quite

as quickly or even more quickly than in any other line, and are

interested enough in their own welfare and development to seek

the best wherever it is to be found; therefore, these Eastern men

[scholars with whom Boucher had consulted] predicted, if Chicago

12. e plan that Boucher brought before the University Senate was not a for-

mal legislative proposal for that body, but rather a series of recommendations

that would have to be considered rst by the Faculty of the Colleges of Arts,

Literature, and Science. is faculty met on May 15, 1928, and agreed to create

two boards—one for the junior-college curriculum and one for the senior-col-

lege curriculum—to evaluate Boucher’s proposals and then report back to the

full faculty. e boards began to meet in the autumn quarter of 1928, but it

soon became apparent that, lacking the presence of the new (and, as of yet,

unnamed) president, it would be dicult to establish sucient political consen-

sus as to how to proceed.

JOHN W. BOYER13

were to adopt such a plan as here outlined, it would at once be

recognized the country over as a performance superior to the old

stereotyped and almost universal plan, and in a short time Chicago

would have more applicants of better quality than ever before.

13

For his basic instructional model Boucher adapted and expanded the

structural idea of an interdisciplinary, trans-departmental “survey course”

for freshmen in the natural sciences, entitled e Nature of the World

and Man, that H. H. Newman and others in Biology had organized for

sixty students each year beginning in 1924. is course, whose major

organizing theme was the trajectory of human evolution, was taught on

a two-quarter cycle, and by 1928 had 240 students. e Newman course

aimed “to make clear the fact that all science is one and that there are no

hard and fast lines between its various branches.” Newman and his col-

leagues, who included Rollin T. Chamberlin, Anton J. Carlson, Harvey

B. Lemon, Merle Coulter, Fay-Cooper Cole, Julius Stieglitz, Charles H.

Judd, and others, had the striking goal in mind of presenting students

with “a general philosophic view that will rationalize all of the order and

unity in the natural universe.”

14

Boucher used this course as a template

for his larger and more ambitious plans to restructure the undergraduate

curriculum as a whole.

15

13. Boucher, “Supplementary Statement,” May 1, 1928, 16, ibid.

14. H. H. Newman, e Nature of the World and of Man, Dean of the College

Records, 1923–1958, box 5, folder 4. In 1926 Newman also published a formi-

dable 550-page book, bringing together essays of sixteen collaborators who taught

in the course, entitled e Nature of the World and of Man (Chicago, 1926).

15. Chauncey S. Boucher, e Chicago College Plan (Chicago, 1935), 17.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 14

A crucial turning point that put Boucher’s eorts back on track toward

stunning success came in the summer of 1929, when the young Yale Law

School dean, Robert Maynard Hutchins, assumed the presidency of the

University of Chicago. Immediately after Hutchins’s appointment was

announced in April 1929, Boucher wrote two back-to-back letters to

him, duly praising his appointment but also informing and lobbying

Hutchins about his (Boucher’s) plans. Boucher noted: “After a year of

uncertainty, with the consideration of important questions of basic policy

necessarily postponed, the election of anybody as president at this time

would have given us a feeling of relief. But, your acceptance of the presi-

dency has given us genuine satisfaction and has inspired us anew with

enthusiasm and condence.” For Boucher “the most important project

in educational policy which was before us for consideration when Presi-

dent Mason’s resignation was announced is set forth in the report of the

Senate Committee on the Undergraduate Colleges, dated May 1, 1928.”

16

Boucher proved to be an able advocate, and Hutchins slowly came to

embrace the basic substance of Boucher’s plan. us did Boucher gain a

powerful ally who, as the new executive leader with the sovereign force

of the presidency behind him, had the political resources and the moral

authority to force Boucher’s schemes through the faculty. Once Hutchins

had determined in the autumn of 1930 to restructure the University to

create four separate graduate divisions, it became logical to create an

administratively separate college as well.

17

Boucher’s conceptual ideas on

a new curriculum for such a college and Hutchins’s structural reforms

16. Boucher to Hutchins, April 27, 1929, and May 3, 1929, Dean of the Col-

lege Records, 1923–1958, box 1.

17. See John W. Boyer, e Organization of the College and the Divisions in the

1920s and 1930s (Chicago, 2002), 10-64.

JOHN W. BOYER15

converged, and beginning in late December 1930 Boucher chaired an ad

hoc curriculum committee which crafted, over the course of two months,

a curriculum for the College whose centerpiece was a set of four year-long

general-education survey courses, with an additional survey in English

composition.

18

e new survey courses were to be administered by clus-

ters of faculty drawn from the four divisions, but under the administrative

and curricular aegis of the separate College.

19

Originally, Boucher

intended that most of the faculty participating in the College would have

simultaneous departmental memberships. It is of great importance to

remember that Boucher had no intention of creating a faculty separate

from and in opposition to the departments and the divisions. e Uni-

versity Senate concurred in this view when it authorized the College in

1932 to hire faculty members who did not have departmental member-

ships, but cautioned, “it is considered desirable that a large proportion of

the College faculty be members of Departments and Divisional faculties.”

20

Boucher was well aware that the audience for his new program con-

sisted of many students who sought careers in the professions or in

18. e committee solicited reactions from the faculty and received a number

of thoughtful commentaries in late January 1931, which are led in the Presi-

dents’ Papers, 1925–1945, box 19, folder 9. e nal proposal, dated February

7, 1931, is in ibid., folder 8. Hutchins followed the work of the committee

closely, and met with them at least twice to discuss their progress.

19. See Chauncey S. Boucher, “Procedures to Put the Plan into Operation,”

November 1930, Dean of the College Records, 1923–1958, box 10, folder 2. A

convenient overview of the actual plan is oered by “First Year of New Plan in

the College,” ibid. See also Boucher to Hutchins, October 16, 1930, with a

memo on “e College Curriculum,” Presidents’ Papers, 1925–1945, box 19,

folder 7.

20. “Minutes of the University Senate,” November 19, 1932.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 16

business and not in academic life.

21

Hence he tried to make his vision

appealing to a broad range of students, stressing the timeliness and func-

tional utility of a general-education program for students who wished to

undertake careers in business, law, and medicine. Boucher insisted that

“general education provides the basis for an intelligent discharge of these

larger responsibilities which inevitably come to the man or woman who

is really successful in a profession or vocation.” But even for those who

did desire academic careers general education was vital, since “the special-

ist in any eld should be characterized by the wealth of his knowledge of

many elds. To be only an expert results in a one-sided personality and

limited usefulness.”

22

All of this was to connect the New Plan to the world

and to emphasize its relevance for professional careers outside as well as

inside of the academy.

After securing the approval of the new curriculum by a vote of 65 to

24 at a general meeting of the Faculty of the College in early March 1931,

and after conferring with the newly appointed divisional deans and with

key department chairmen, Chauncey Boucher set out to organize four

planning groups to create the new survey courses. e groups worked

quickly and assembled necessary course materials, which Boucher found

21. See Chauncey S. Boucher, e New College Plan of the University of Chicago

(Chicago, 1930), 5–6, 9, 14. A survey undertaken in 1932 of prospective stu-

dent careers found that 27 percent of the male students intended careers in law,

20 percent in medicine, and 16 percent in business, advertising, or engineering.

Seven percent intended careers in teaching, and 17 percent in science, with 5

percent wanting careers in journalism. See Robert C. Woellner, “e Selection

of Vocations by the 1932 Freshmen of the University of Chicago,” Dean of the

College Records, 1923–1958, box 6, folder 6.

22. “Education and Careers” (Chicago, n.d.), 1. e pamphlet is unsigned, but

was clearly by Boucher or under his direction.

JOHN W. BOYER17

the funds to purchase. Each course produced a detailed syllabus, which

included a prose outline of the major arguments and material of the

course together with detailed bibliographical citations for further reading.

Substantial investments in books and equipment had to be made.

Boucher also held several meetings in the spring of 1931 where all sta

leaders met jointly to work out logistical and scheduling issues. Slowly,

the appearance of a unied curriculum emerged. A key feature of the new

general-education curriculum was that it would not depend on course

grades but on six-hour nal comprehensive exams administered by an

independent Oce of the Examiner, headed by Professor Louis L. ur-

stone, a distinguished psychologist who did pioneering research in

psychometrics and psychophysics. Students could pace themselves

through the curriculum, taking the nal comprehensives whenever they

felt prepared to do so. e idea of individual agency, cast as the autonomy

of student freedom, was a central feature of the logic of the New Plan.

23

Attendance at the general-education survey courses was not manda-

tory to prepare for the comprehensive exams, although in most cases

most students seem to have attended the course lectures. Students could

register either for audit or for advisory grades, and most of the courses

oered quarterly exams, papers, and quizzes that were intended to serve

an advisory function, allowing a student to measure his or her progress

within the course. e advisory grades did not convey graduation credit,

however, since the comprehensive exams were the basis of receiving the

23. For the history of the Board of Examinations, see Benjamin S. Bloom,

“Changing Conceptions of Examining at the University of Chicago,” in Evalu-

ation in General Education, ed. Paul L. Dressel (Dubuque, Iowa, 1954),

297–321.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 18

College’s certicate.

24

Grades were thus used only as advisory instruments,

or to facilitate transfer credit if a student opted to move to another college.

THE BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES

AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES

GENERAL COURSES

n the natural sciences Boucher had the advantage of

being able to drawn upon a group of men who had

already participated in e Nature of the World and

Man course. e world of the natural sciences at Chi-

cago in the late 1920s was exciting and lled with ambitious scholars,

optimistic about the progress of their disciplines and certain that the new

knowledge of modern science could be made both appealing to and

relevant for a general undergraduate audience. e primary architect of

the Biology course was Merle C. Coulter from the Department of Botany.

Coulter was the son of John M. Coulter, the founder of modern botany

at Chicago, with whom the younger Coulter had collaborated in writing

a book defending modern evolutionary theories in 1926.

25

He was a

product of Chicago, having received his undergraduate degree in 1914

and his PhD in 1919. As a young assistant professor Merle Coulter had

24. “e marks made in the comprehensive examinations, and not the quarterly

reports, constitute the final record for purposes of fulfilling College

requirements, awarding scholarships and honors, and fullling requirements for

admission to a Division.” A. J. Brumbaugh to M. C. Coulter et al., October 15,

1936, Dean of the College Records, 1923–1958, box 6, folder 9.

25. John M. Coulter and Merle C. Coulter, Where Evolution and Religion Meet

(New York, 1926).

I

JOHN W. BOYER19

been a collaborator in e Nature of the World and Man, preparing a

chapter of the textbook that accompanied that course. In 1930 he was

an associate professor of botany, a man of considerable diplomatic skill,

and an inspiring teacher. He did not enjoy the research reputation of his

father, which he always regretted, but the General Biology course enabled

him to make a signicant professional contribution at the University.

26

When Chauncey Boucher asked him to lead the planning eort to get

the new sequence o the ground, Coulter was eager to do so.

Coulter organized a course that depended on the cooperation of a

number of other senior biologists, each of whom agreed to give several

lectures in the course. He was assisted in his lectures by a team of younger

biologists, including Alfred E. Emerson and Ralph Buchsbaum from

Zoology and Ralph W. Gerard from Physiology, several of whom would

go on to distinguished scholarly careers in the Division of the Biological

Sciences. More senior members were also invited to give lectures, includ-

ing Warder C. Allee, Fay-Cooper Cole, Lester R. Dragstedt, and Alfred

S. Romer, with perhaps the most notable scholar being A. J. Carlson,

popularly known as Ajax Carlson, a distinguished physiologist who gave

fteen lectures during the academic year and became one of the most

beloved general-education faculty teachers in the College before World

26. Joseph Schwab later argued that Coulter had always stood in the shadow of

his father, and his participation in the Biology course oered him a way to com-

pensate for this situation: “He felt he should have been what his father had been,

a research man. He kept up with the literature in the eld, he read, he always

had a rapport with the papers that were being printed and published and so

on.…Anyway, he had a research ideal which he did not fulll.” Interview of

Joseph J. Schwab with Christopher Kimball, April 7, 1987, 59–60, Oral History

Program.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 20

War II.

27

Born in Sweden, Carlson came to America at the age of sixteen

in 1891 knowing not a word of English. He worked as a carpenter’s

apprentice and planned on becoming Lutheran minister. But he soon

became interested in physiology and ended up at Stanford, where he took

a PhD in 1902. In 1904 Harper hired him as an instructor at Chicago,

and by 1914 he was a full professor of physiology. Carlson was legendary

for asking his students in his heavy Swedish accent the formidable ques-

tion: “What is the evidence?” at students were often befuddled and

even terried as to how to answer Carlson’s questions seemed to make

him all the more appealing as a lecturer. Joseph Schwab remembered him

as someone who “took no nonsense, he didn’t talk professorese, he was a

toughie.”

28

Edwin P. Jordan, a former student who became the director

of education at the Cleveland Clinic, recalled that “in creating a state of

mind of skepticism, coupled with a desire to learn more, but to do this

only on the basis of the scientic method, you have surely had an enor-

mous inuence not only on those who were directly touched by your

teaching and investigative methods but also on their students and their

students’ students as well.”

29

Merle Coulter later observed of Carlson’s

role in the Biological Sciences general course, “you were usually our chief

oensive threat and a tower of strength on defense.”

30

at a scholar of

Carlson’s stature was steadily devoted to the Biological Sciences general

course as a matter of professional responsibility made its success all the

27. Lester R. Dragstedt, “Anton Julius Carlson, January 29, 1875–September

2, 1956,” Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences 35

(1961): 1–32; and idem, “An American by Choice: A Story about Dr. A. J.

Carlson,” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 7 (1984): 145–58.

28. Interview of Joseph J. Schwab with Christopher Kimball, April 7, 1987, 34.

29. Jordan to Carlson, December 28, 1949, Anton J. Carlson Papers, box 1.

30. Coulter to Carlson, January 29, 1950, ibid.

JOHN W. BOYER21

easier. But Carlson’s ferocious empiricism and condent assaying of “the

facts” of any intellectual problem was to become a subject of a campus-

wide debate in 1934.

Merle Coulter was particularly proud that students would encounter

“the most distinguished authority” in a specic eld, thereby enabling

the course to generate a “real ‘University tone’” by giving rst- and sec-

ond-year students “contact with many of the most outstanding men on

our University faculty.”

31

In addition to the formal lectures students par-

ticipated in weekly discussion conferences and also had access to what

Coulter called “laboratory exhibits.” Attendance at the latter was optional,

31. Merle Coulter, “Report on Ten Years of Experience with the Introductory

General Course in the Biological Sciences,” October 1941, 8, Dean of the Col-

lege Records, 1923–1958, box 5, folder 8.

Merle C. Coulter, undated

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 22

but Coulter reported in 1935 that “most of the students of previous years

have attended regularly and have found these exhibits to be one of the

most interesting and valuable parts of the course.”

32

Coulter’s group crafted their outline, in considerable detail, during

the spring of 1931. e course was intended to help cultivate “the scien-

tic attitude of mind” among students by exposing them to various

examples of the application of the scientic methods, to provide a level

of basic knowledge of biology as would be needed by “a modern citizen,”

and to encourage among students an interest in “the grand machinery of

the organic world and in the major concepts of biology.” e course was

divided into four major parts: a survey of the plant and animal kingdoms;

an analysis of the dynamics of living organisms, including physiology and

psychology; studies in evolution, heredity, and eugenics, and a section

on ecology; and the adaptation of living organisms to their environment

and to each other.

33

e autumn quarter focused on giving the student

an evolutionary portrait of the organic world, moving from the plant

kingdom to invertebrate and vertebrate animals to the most complex

animal, the human being. e winter quarter then focused directly on the

nature of human life, with lectures on blood, heart, respiration, digestion,

enzymes, the kidneys and endocrine glands, the nervous system, nutrition,

bacteria, and disease. e nal part of the course related man to the world

around him, using ecology and evolution as its central focus. Here the stu-

dents heard lectures on evolution, heredity, mutation, eugenics, and ecology.

e course gained a strong coherence by its focus on the major con-

cepts of evolution, structure, and function within the domain of biological

32. “General Introductory Course in Biological Science: Schedule of Confer-

ences and Lectures, Autumn, 1935,” ibid., box 6, folder 9.

33. “e General Course in Biological Science,” [1931], ibid.

JOHN W. BOYER23

phenomena. Its inductive and experimental approach and its frequent

invocation of the physical and chemical basis of human life and of the

chemical and physical knowledge required to understand such processes

as photosynthesis and respiration or the functioning of the nervous

system aorded the course natural links to the material covered in the

Physical Sciences general course. Coulter felt that it was especially valuable

to give the student an understanding of and a respect for the unbi-

ased method of thinking that characterizes, or should characterize,

workers in the eld of natural science.…We hoped to drill the

student in such a manner to improve his ability to think scientically

and/or strengthen his habit of thinking in this way. Recognizing

that other courses on our campus would be aiming at the same

general objective, we felt it appropriate for our course to stress that

particular tool of the scientic method which modern biology cher-

ishes most highly—controlled experimentation.

34

Coulter’s emphasis on the virtues of the scientic method, as customary

and conventional as it might seem to us today, was in fact a decision of

great curricular import, for it set the New Plan in a skills-oriented direc-

tion that transcended the conveying of raw data and factual information.

It conrmed the excitement and prestige of science in the interwar period.

e course used a range of review materials, quizzes, and papers to

achieve these noble ends, although these were only advisory and not for

credit. In addition to the lectures and discussion conferences Coulter also

organized each week an optional laboratory demonstration. Students

were not permitted to handle specimens or equipment, so their role was

34. Coulter, “Report on Ten Years of Experience with the Introductory General

Course in the Biological Sciences,” 2.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 24

to be one of the interested observer, not an active participant. Coulter

actually believed that this was a more eective pedagogical approach since

“more than once it has been remarked by adult visitors to some of our

laboratory demonstrations that a half-hour of this type of thing is more

valuable to the average student than a month of old-fashioned laboratory

work.” In 1934 Coulter estimated that between 60 and 70 percent of the

students regularly attended the laboratory demonstrations.

35

Coulter and his colleagues also pioneered the production of a series

of short motion pictures with ERPI Classroom Films that provided dem-

onstrations of experiments on such topic as the Heart and Circulation,

Mechanisms for Breathing, Digestion of Foods, the Work of the Kidneys,

the Endocrine Glands, the Nervous System, and Heredity. By 1940

eleven such lms had been produced, and Coulter was proud that all of

them were “good and some of them are remarkably good.” e lms were

designed so that they appealed to more general audiences beyond uni-

versity students, enabling viewers to see and understand complex

biological processes “even more clearly than if they had been present in

the laboratory.” Coulter also admitted, “for better or worse, most of our

young American students like the movies and are stimulated to an

increased interest in biology by an occasional movie presentation.”

36

Among College students the Biological Sciences general course quickly

became the most popular of the four general-education courses, and its

coherent organization, overarching themes, and logical rhythm certainly

contributed to that state of aairs. But there was also the quiet certainty

35. Statement by Merle Coulter, September 14, 1934, Dean of the College

Records, 1923–1958, box 6, folder 9.

36. Coulter, “Report on Ten Years of Experience with the Introductory General

Course in the Biological Sciences,” 18–19.

JOHN W. BOYER25

and condence that the course was genuinely important for young stu-

dents, not only as citizens but as inhabitants of a closely and intimately

shared natural world. Anton Carlson was particularly insistent: “the

understanding of the physical man himself and his environment, the

adjustment to and the control of his environment cannot be foreign to

genuine liberal education.”

37

e parallel course in the physical sciences was organized by Harvey

B. Lemon, a physicist who completed his undergraduate studies at

Chicago (BA, 1906) and who had studied with Albert A. Michelson

and Henry Gale at Chicago for the doctorate, completing a dissertation

on spectroscopic studies of hydrogen in 1912. Lemon was interested

in pedagogy, and authored several articles in the 1920s on the use of

intelligence tests to diagnose the capability of students to succeed in

science courses.

38

Lemon was a scholar of wide-ranging interests with a

air for the dramatic. He was also deeply committed to improving the

teaching of physics, and from 1937–39 served as the president of the

American Association of Physics Teachers. He also exercised stringent

standards in the hiring of course assistants, noting that if one specic

graduate student did not conduct himself in a “thoroughly dignied and

grown-up fashion,” he would “nd himself demoted to the laboratory.”

39

37. Anton J. Carlson, “e Oerings and Facilities in the Natural Sciences in

the Liberal Arts Colleges,” e North Central Association Quarterly 18 (1943): 162.

38. Harvey B. Lemon, “Forecasting Failures in College Classes,” e School

Review 30 (1922): 382–87; idem, “Preliminary Intelligence Testing in the

Department of Physics, University of Chicago,” School Science and Mathematics

20 (1920): 226–31.

39. Lemon to Gale, June 6, 1936, Department of Physics Records, 1937–2002,

box 9, folder 17.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 26

Lemon was joined in the course by a distinguished chemist, Hermann

Schlesinger, who had also received both his BA and PhD degrees at the

University of Chicago, studying with Julius Stieglitz. Schlesinger joined

the faculty in 1910 and was promoted to full professor in 1922; he even-

tually won the Priestly Medal of the American Chemical Society. Others

who gave lectures included Gilbert A. Bliss, Otto Struve, Arthur H.

Compton, William Bartky, J. Harlen Bretz, and other distinguished

scholars, thus giving young College students a chance to encounter

prominent scholars from across the division.

40

e new course sought to integrate astronomy, mathematics, physics,

chemistry, and geology into one year-long survey. It started with the

earth as an astronomical body, considering the structure of the universe,

the nature of planets and stars and their evolutionary origins; it contin-

ued with a survey of essential components of the physical sciences,

beginning with the fundamental laws of energy, heat, and temperature

as manifestations of atomic and molecular motions, and the nature of

electricity, sound, light, and X-rays as examples of the phenomena of

waves; and it continued with a study of basic chemistry, chemical ele-

ments, compounds, mixtures, solutions, and colloids; it followed with

atomic weights and numbers, chemical transformations, the periodic

system, chemical reactions, the atmosphere, ionization, and carbon com-

pounds; and the course concluded with a study of the geological features

of the earth, rocks, minerals, the formation of the mountains and oceans,

climatic changes, and fossils as a geological record of life.

Both the Biological Sciences and Physical Sciences general courses

were organized in a lecture-discussion format, having three lectures plus

40. A detailed history of the course is provided by ornton W. Page in “e

Two-Year Program: Physical Sciences,” November 1949, Presidents’ Papers,

1946–1950, box 12, folder 5.

JOHN W. BOYER27

one discussion a week. Both courses styled themselves as “state of the

art” in scholarly terms, and both proted from that crescendo of self-

condence about the importance of the natural sciences to human life

that enveloped American research universities after World War I. e

war had given American scientists powerful opportunities to demon-

strate the practical impact of modern science, not only for human

destruction but also for human regeneration and reconciliation. On our

campus, for example, Julius Stieglitz, the chair of Chemistry, who par-

ticipated in the development of e Nature of the World and Man

course, was a bold and articulate spokesman for the view that chemistry

was a crucial partner for modern medicine and modern pharmacology:

“chemistry is the fundamental science of the transformation of matter,

and the transformation of matter almost at will obviously has inherent

in itself the realization of unlimited possibilities for good.”

41

Stieglitz

was also a strong advocate of integrating the intellectual standards associ-

ated with advanced scientic research and graduate education into the

undergraduate curriculum. He was convinced that the University of

Chicago should

develop to the utmost its singular opportunity for the most inspir-

ing type of college education, resulting from the co-existence in a

single institution of great graduate departments and great colleges

crowded with eager thousands—the red blood of universities.…

Situated in the heart of the American nation, why should it hesitate

to try the experiment of giving to its four years of college life every

last ounce of benet from the presence of its great graduate faculties

and, reciprocally, of increasing the strength and research output of

41. Julius Stieglitz, Chemistry in the Service of Man (Chicago, 1925), 9.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 28

its graduate schools in the manning of its college chairs and thus

develop to the utmost the American university.

42

Equally noteworthy was the greater sense of interdependence of vari-

ous disciplines in the natural sciences, and the need for close collaboration

across the disciplines to attain path-breaking conceptual and empirical

discoveries. A proposal by Ezra J. Kraus of the Department of Botany in

late 1927 to create an interdisciplinary Institute of Biology insisted that

“the [fundamental biological] problems, rather than the departments of

the university should serve as points of attack. us the work of perhaps

several men in various departments could be coordinated and focused

on a problem.”

43

Vice President Frederic Woodward said that Kraus was

“a great believer in cooperative research,” and was “struck by the similarity

of the situation in the biological and social sciences. He made a great

impression on me and I think we should encourage him and back him

up at every possible point.”

44

As a young physicist writing in the early

1920s, Harvey Lemon was equally condent that science was on the

threshold of enormous changes that educated men and women must

understand, if only to prevent the kind of misuse of science that had (to

his mind) taken place between 1914 and 1918:

Clear heads and sober minds are needed, as never before, to watch

lest the genie prove to be an evil one providing us with the weapons

42. Julius Stieglitz, “e Past and the Present,” e University of Chicago Maga-

zine, March 1929, 233–39, here 239.

43. Kraus to Max Mason, October 24, 1927, “Institute of Biology,” Presidents’

Papers, 1889–1925, box 101, folder 1.

44. Woodward to Mason, August 29, 1927, ibid.

JOHN W. BOYER29

for our own destruction. e dreams of Jules Verne that red the

imagination of our boyhood, incredible as they then appeared, are

today in many instances accomplished facts.…As individuals in

social and political life, we must keep pace with science; and, taking

the warning from the fate of [Henry] Moseley, prevent the repeti-

tion of another such orgy of destruction as that which recently was

detonated by the monumental stupidity of our so-called

civilization.

45

Lemon later insisted that science was not simply about generating ever

more remarkable technical applications:

Applications of science have not been, and never will be, the chief

motive of the scientic investigator or student. e study of pure

science will never be abandoned as long as human beings are char-

acterized by a certain element of curiosity with respect to their

environment.…In our continuing eorts to a better and better

understanding of things which perhaps we shall not fully under-

stand for many centuries yet to come, if ever, we nd the greatest

interest and the most driving motive in the pursuit of scientic

studies.

46

45. Harvey B. Lemon, “New Vistas of Atomic Structure,” e Scientic Monthly

17 (1923): 181.

46. Harvey B. Lemon and Niel F. Beardsley, Experimental Mechanics: An Ana-

lytical College Text (Chicago, 1935), 6.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 30

THE HUMANITIES AND

SOCIAL SCIENCES GENERAL

COURSES

f the two natural-sciences courses emerged from cur-

ricular projects of the 1920s, the new general Humanities

course had an even deeper institutional history. e

main architect was an elderly history professor, Ferdi-

nand Schevill, whose initial appointment to Chicago originated in 1892.

Schevill had a fascinating career. Born in Cincinnati in 1868 Schevill

attended Yale University as an undergraduate, at the same time that

William Rainey Harper was on the faculty. Schevill took Harper’s course

on the Hebrew prophets, establishing a personal relationship that even-

tually led to Schevill’s coming to Chicago. After graduating from Yale

he went to Germany to study for a PhD in history, working at the Uni-

versity of Freiburg with, among others, Hermann von Holst. In 1892

Harper oered Schevill a job for eight hundred dollars as an “Assistant

in History” on the recommendation of Charles F. Kent, a former student

of Harper’s at Yale who was studying Hebrew in Berlin and who

reminded Harper that Schevill was one of the “brightest men” in the

Yale graduating class of 1889.

47

Such informality was typical of the times,

47. Kent to Harper, October 1, 1891, William Rainey Harper Papers, box 14,

folder 30. Schevill’s birth name was Schwill, which he anglicized in 1909. Urged

by Kent, Schevill wrote to Harper on October 17, 1891, re-introducing himself

and presenting his credentials. Schevill to Harper, October 17, 1891, ibid.

Harper received a similar suggestion from George S. Goodspeed, who informed

Harper of a recent meeting with Schevill and who allowed that “he…strikes me

as a very bright man. I think if you could put him in as a docent at Chicago, you

would not be mistaken at all.” Goodspeed to Harper, October 25, 1891, ibid.,

box 12, folder 34.

I

JOHN W. BOYER31

and Schevill came to Chicago knowing little or nothing of the prehistory

of the new University.

Ferdinand Schevill soon proved to be an amiable colleague and a

brilliant teacher.

48

He was particularly close to a remarkable social circle

of young humanists in the later 1890s who met regularly and included

John Mathews Manly, Robert Herrick, Robert Lovett, and William

Vaughn Moody, a reminder of how dependent the early faculty were on

each other for intellectual and cultural sustenance.

49

Schevill never liked

the University as an administrative community, and when he warned

his personal friend Frank Lloyd Wright that the University High School

was like “all schools, established churches, minister-blest marriages, and

all other sacred institutions” in that “to play with any one of them is

alas! alas! to toss yourself into a buzz-saw,” he was alluding to his own

iconoclastic relationship with Chicago.

50

48. e distinguished American historian Howard K. Beale of the University of

Wisconsin many years later remembered that Schevill “was the greatest teacher

I had ever sat under. He was, of course, one of the most cultivated persons and

delightful companions I have ever known. Above all else he was a great human

being. I still feel the inspiration he gave me when I took his courses as an under-

graduate.” Beale to James L. Cate, December 31, 1956, James L. Cate Papers,

box 4.

49. Robert M. Lovett, All Our Years: e Autobiography of Robert Morss Lovett

(New York, 1948), 97–98. Robert Herrick later remembered: “e half dozen

of us young men who had come to the new world together naturally formed the

closest sort of fellowship. We were like a company of the celebrated musketeers,

disturbers of the academic peace and scoers often, but really devoted to our

work and faithful. We may have cast regretful glances half of homesickness back-

ward to that pleasant East from which we came, but we were faithful to the hope

of the West.” “Going West,” 6–7, Robert Herrick Papers, box 3, folder 10.

50. Schevill to Wright, September 4, 1916, Frank Lloyd Wright Papers, micro-

che copy at the Getty Research Institute.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 32

Schevill began his scholarly career with studies of the medieval Italian

communes. His rst major book was a study of the free republic of Siena

in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and it highlighted a major

theme in Schevill’s thought: the tension between the universal and the

particular, between monarchy, which represented order and civility, and

communal self-government, which sponsored freedom and democracy.

Schevill believed that free communes like Siena had “endowed man with

a new conception of his powers and purposes.” ey created “a new civi-

lization, a civilization, in fact, with the elaboration of which the world

had been occupied down to our own day.”

51

A similar conceptual frame-

work informed Schevill’s later book on the Renaissance city-state of

Florence, published in 1936. Schevill would later argue that both of these

impulses—order and freedom—were already present in the ancient

world, and that it was thus logical to begin the study of European civiliza-

tion with Greece and Rome.

52

Of the many members of the early Chicago

faculty who had studied in Europe, Ferdinand Schevill was perhaps the

one most transformed by European values and European culture. He

once confessed to his friend Sherwood Anderson, “in America I often

have the feeling that I belong to Europe, and in Europe I reach the deep

51. Ferdinand Schevill, Siena, the Story of a Medieval Commune (New York,

1909), 420–21.

52. “e outstanding forms evolved by the Mediterranean peoples are two:

monarchy and the self-governing city-state. Monarchy represents the tendency

toward unity and peace; the city-state the tendency towards freedom and self-

determination. e balance between unity and freedom is indicated as the

political problem of mankind.” Schevill to Baker Brownell, November 26, 1924,

Baker Brownell Papers, box 9, folder 4, Northwestern University Archives. See

also Ferdinand Schevill, “Man’s Political History,” in Man and His World: North-

western University Essays in Contemporary ought, ed. Baker Brownell, vol. 4,

Making Mankind (New York, 1929), 145–76.

JOHN W. BOYER33

conclusion that my roots are in American soil.”

53

He traveled frequently

across Europe, gaining an intimate, rsthand knowledge of European art

and architecture and often took friends and the children of colleagues on

cycling and walking tours of France, Germany, and his beloved Italy.

54

During World War I Schevill was one of a small minority of faculty

who opposed America’s entrance into the war, further isolating him from

the mainline faculty politics of Chicago, and by the early 1920s he had

tired of teaching, indicating to President Ernest D. Burton in 1923 that

he intended to resign to pursue a full-time career in writing.

55

Burton

persuaded Schevill to stay on a part-time basis until 1927, when he left

the University for good, or so he thought. Schevill had looked forward

to a life beyond the institutional claims of the University, but by 1930

he was almost broke, having loaned substantial sums to friends who were

in distress because of the Depression, and part of his motivation to return

to teaching may have been nancial urgency.

56

When Boucher contacted

him in early 1931 about returning to the University to take up the great

challenge of the new Humanities course, Schevill was thus easily per-

suaded both by the substantial salary that Boucher oered him and by

53. Schevill to Sherwood Anderson, written while Schevill was visiting Vienna,

November 13, 1927, Sherwood Anderson Papers, box 27, Newberry Library.

54. See, for example, Lovett, All Our Years, 71-89, 106–20; William Vaughn

Moody, “European Diary,” 28–33, William Vaughn Moody Papers, box 1,

folder 9. e Chicago sociologist Everett C. Hughes later remembered that

Schevill took the son of W. I. omas on a walking tour of Italy. Hughes

to Mary Bolton Wirth, May 31, 1968, Mary Bolton Wirth Papers, box 5,

folder 1.

55. Schevill to Burton, December 27, 1923, Presidents’ Papers, 1889–1925, box

59, folder 21.

56. Schevill to Frank Lloyd Wright, October 19, 1930, Frank Lloyd Wright

Papers. Schevill also faced heavy medical bills arising from his wife’s illness.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 34

the challenge to nally leave his mark on the teaching of European civi-

lization to newly minted college students.

57

World War I had come as a deep shock to Ferdinand Schevill, who

believed that the war had threatened the fundamental values of cultural

balance and material progress that had marked European civilization

up to 1914. e world of the 1920s was one dominated by “revolutionary

monstrosities” in Europe and “heaped-up wealth” in America.

58

For a

bourgeois humanist rooted in the culture of late nineteenth-century

Central Europe, both continents seemed to be veering o course, into

crass materialism and social upheaval. To Frank Lloyd Wright Schevill

argued in 1927, “ours is a government by the mob,” and by 1932 he

would insist that

the more I turn the present diculties over in my mind, the more

convinced I am the issue is quite simply between two kinds of

society. Either the acquisitive society we’ve got or a friendly com-

monwealth of approximate economic equals. Maybe the acquisitive

society is all we are capable of with our inheritance and animal

equipment. In that case we shall continue to struggle in the back

slough in which the human race has been immersed from the

beginning. But if we are to make a try for the other thing—and

I say, let’s go—we ought to be perfectly clear that it is a whole-

57. Boucher to Filbey and Woodward, March 13, 1931, Dean of the College

Records, 1923–1958, box 7, folder 2. Schevill was oered an annual salary of

$7,500, a very substantial sum for the time.

58. Schevill to Anderson, September 22, 1923, and November 13, 1927, Sher-

wood Anderson Papers, box 27.

JOHN W. BOYER35

hog or nothing proposition and that pacism, third-parties and

melioratives are distractions that darken the issue.

59

Schevill was a prolic writer, espousing the nineteenth-century Euro-

pean tradition of writing history for the educated general reader. He

once argued that

I kept in mind a prospective audience, composed, not of a small

group of specialists, but of that larger body of men and women

who constitute a spiritual brotherhood by reason of their common

interest in the treasure of the past.…I make bold to arm my

belief that scholarship practiced as the secret cult of a few initiates,

amidst the jealous and watchful exclusion of the public, may in-

deed succeed in preserving its principles from contamination, but

must pay for the immunity obtained with the failure of the social

and educational purposes which are its noblest justication.

60

Schevill thus believed that history’s largest purpose was to ennoble as well

as to educate the general reader, and in his teaching at the University of

Chicago he pursued the same objectives, making him an ideal and much

cherished teacher who sought to encourage the student’s cultural self-

development and intellectual maturity. In a sense, Schevill was deeply

involved in the project of general education long before the phrase

became a popular educational concept in the 1930s and 1940s.

59. Schevill to Wright, February 16, 1927, Frank Lloyd Wright Papers; Schevill

to Anderson, September 26, 1932, Sherwood Anderson Papers, box 27.

60. Schevill, Siena, v.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 36

Schevill’s most successful book was his History of Modern Europe, rst

published in 1898 and revised continuously until 1946. e 1925 edition

reveals many of the arguments that would have informed his approach

to teaching European history. Schevill believed that Europe had over a

thousand years nurtured a European civilization that was perhaps the

most powerful and far-reaching of world civilizations, since it included

the United States within its cultural and intellectual compass. e United

States was a “passionate, struggling, and inseparable element” of a larger

European civilization, and this gave special urgency and authority to the

project of teaching European history to young Americans.

61

Yet after

World War I, a war that he profoundly regretted, Ferdinand Schevill’s

story of a slow, but positive evolution of European civilization was vastly

complicated by the ruptures of the Treaty of Versailles. By the later 1920s,

he was in the fascinating but also perplexing situation of having to imag-

ine the portrait of a Europe that he viewed with both admiration and

disillusionment, which could be proered to young Americans. In the

end, the course that he designed was much more of the rst than the

second, having little to do with a twentieth century that Schevill found

dispiriting and depressing.

Schevill was assisted by Arthur P. Scott, then a mid-career associate

professor of history who was a departmental jack-of-all-trades, and (to a

much lesser extent) by Hayward Keniston, an associate professor of Span-

ish philology and comparative linguistics who eventually left Chicago for

the University of Michigan. A graduate of Princeton, Scott had received

his PhD from Chicago in 1916. Scott had lived for several years in Beirut

and had a special interest in the expansion of Europe. He was also an

authority on colonial American law, publishing a book on criminal law

61. Ferdinand Schevill, A History of Europe from the Reformation to Our Own

Day (New York, 1925), 4.

JOHN W. BOYER37

in colonial Virginia, and he regularly taught courses on US history as

well. In the 1920s he taught an introductory survey in the Department

of History on the History of European Civilization, based on a strict

chronological framework. e new Humanities general-education survey

was a collaborative eort, but Ferdinand Schevill provided the major

intellectual imprint on its formation.

62

Arthur Scott later recalled: “we

used to say that whatever the course did for the students, it certainly

educated the sta; and no small element in our education was the inti-

mate and informal contacts with the leader whom we usually addressed

as Maestro, and referred to as the Old Master.”

63

When Schevill died

in 1954, Norman Maclean remembered of the founding of the course

in 1931: “in the history of our university, this moment itself was a Renais-

sance and the atmosphere was charged with excitement, deance, and

promise of adventure.” For Maclean, Schevill’s humanism lay at the heart

of the course, a humanism that was itself “a form of art. He was a historian

of man’s creative activity, and so the Renaissance was his home and Flor-

ence was his city. By this, I mean something more than that he loved

architecture, painting, sculpture, literature, and music. I mean that he

viewed man’s other activities—economic and political and social—as

themselves manifestations of the creative spirit which when fully ourish-

ing as in Florence, is dominated by a desire to attain beauty.”

64

62. See Schevill to Boucher, April 23, 1931, Dean of the College Records,

1923–1958, box 7, folder 2.

63. Arthur Scott, eulogy for Ferdinand Schevill, 1955, Cate Papers, box 4; and

C. Phillip Miller to James L. Cate, March 9, 1955, ibid.

64. Norman Maclean, eulogy for Ferdinand Schevill, 1955, ibid.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 38

Schevill, Scott, and Keniston fashioned a course that wove together

strands of other courses they had taught in the 1910s and 1920s.

65

e

purpose of the course was to expose students to “the cultural history of

mankind as a continuum and as a whole.”

66

Although colleagues in the

Social Sciences later tagged the course as being primarily “aesthetic” and

neglecting political and social history, this was not quite true. Framing

lectures did provide key chronology, but much of the course was on the

history of European ideas, as represented by signicant writers and think-

ers. Students were expected to read substantial parts of classics like

(among many others) the Iliad and Odyssey, Herodotus, ucydides, the

Bible, Dante, Chaucer, Molière, Luther, Shakespeare, Voltaire, Rousseau,

Goethe, Darwin, and Walt Whitman. Many individual poems and other

shorter pieces were also assigned. e aim of the course was to use “his-

tory as a foundation and framework for the presentation of the religion,

philosophy, literature and art of the civilizations which have contributed

most conspicuously to the shaping of the contemporary outlook on life,”

beginning with the civilizations of the Nile and the Tigris-Euphrates

valleys, Greece and Rome, and concluding with “our ruling western civi-

lization,” the latter being “the main object of attention.”

67

Intellectually,

it was clearly the most conservative of the four new general courses, since

65. It might be argued that Boucher privileged his own department in giving

the historians the primary charge of organizing the Humanities general course.

e department had adopted a resolution in early 1931 urging Boucher “to

retain the course on the History of Civilization as part of the oering of either

the Humanities or the Social Sciences Division or both.” Boucher’s decision to

appoint Schevill did essentially that. “Minutes of the Department of History,

January 24, 1931,” Department of History Records, box 19, folder 4.

66. “Preliminary Report of the Committee in Charge of the General Courses in

the Humanities,” Dean of the College Records, 1923–1958, box 7, folder 2.

67. Schevill, “Humanities,” [April 1931], ibid.

JOHN W. BOYER39

it did not seek to break new ground in pedagogical methods or in schol-

arly design. e logic of the course was to convey the rich tapestry of the

European tradition, but a tradition that had experienced profound rup-

ture between 1914 and 1918. e course dealt with World War I and its

aftermath in only two lectures, perhaps because Schevill himself was so

disillusioned by it.

68

Although the history of Western civilization from the ancient world

to contemporary times became the organizing axis, much attention was

also paid to European literature, art, and architecture. American literature

was also included, both for a sense of time and place, but also in a bow to

Schevill’s notion that America was also a part of Western civilization.

e works of art examined in the course were treated in a strongly con-

textualist mode, or as a later commentary noted “that ideas and works

of art are related to the life out of which they arise”

69

e course was an

obvious target for formalists who cared little or nothing about the

encrusted historical exemplariness of their texts and more about the

intrinsic structural properties that dened them as works of art. Still,

the course styled itself as closely attentive to the development of analytic

skills and aesthetic judgment. As Arthur Scott put it in 1933, the

Humanities course aimed to convey a certain amount of information

68. In fact, the initial outline proposed in April 1931, had nothing on the twen-

tieth century, aside from a nal lecture on “is Plural World: e Reigning

Confusion in Our Intellectual and Aesthetic Outlook.” e rst syllabus pub-

lished in September 1931 commented that “the modern world of science and

machines, of national states and world empires, has set in motion forces which

seem to have got out of hand and threaten, like Frankenstein’s monster, to

destroy the civilization which gave rise to them.” Introductory General Course in

the Humanities Syllabus (Chicago, 1931), 328.

69. Arthur P. Scott, “e Humanities General Course. Statement of Objectives,”

May 1939, Dean of the College Records, 1923–1958, box 6, folder 9.

A TWENTIETH-CENTURY COSMOS 40

about European culture that would be of “practical value to young

people presently to be adult members of twentieth century American

society.” But it also sought, “to the limits of its collective ingenuity,” to

encourage and to give practice to “straight and independent habits of

thinking, as by-products of which it may fondly be hoped that a more

critical, rational, tolerant, and broad-minded attitude may be fostered.”

70

To operationalize the course Schevill needed young assistants, and

he found three dedicated men in Norman F. Maclean, Eugene N. Ander-

son, and James L. Cate. Cate, a young medievalist from Texas, and

Anderson, a young German historian from Nebraska, had studied with

Schevill and Scott and were hired rst. Cate in turn told Schevill and

Scott about Norman Maclean and persuaded them to hire his fellow

Westerner from Montana who was a graduate student in the Department