EXAMINING THE PREDICTIVE WEIGHT OF PERCEIVED ORGANIZATIONAL

SUPPORT AND JOB EMBEDDEDNESS ON TURNOVER INTENTION

by

Tyler Swansboro

Liberty University

A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Philosophy

Liberty University

December, 2023

EXAMING POS AND JE 2

ABSTRACT

Generation Z personnel are entering the workplace in monumental numbers. As this

understudied population enters the work domain, the business environment will

continuously struggle to adapt to their new perceptions, motifs, and thought processes.

When these new workers enter the workforce, many will inevitably enter the leisure and

hospitality industry. This specific industry has the highest turnover rate in America

(Bureau of Labor and Statistics, 2022). To further the understanding of retention, this

study was structured to explore the predictive weight of perceived organizational support

(POS) and job embeddedness (JE) on turnover intention, to assess which construct was

the stronger predictor. Answering a call for future research, the sample was derived from

Generation Z employees (participants aged 18 to 25) who have worked or are working in

the leisure and hospitality sector for at least 6 months and did not hold a supervisory role.

68 participants filled out an online survey containing three psychological measurements

(POS, JE, turnover intention scale) that were posted in preapproved social media groups.

A multiple linear regression analysis was employed and revealed that POS is the only

predictor of turnover intention among Generation Z employees working in the American

leisure and hospitality industry. Implications and direction for future research are

discussed.

Keywords: Generation Z, leisure and hospitality, perceived organizational

support, job embeddedness, turnover intention, retention, multiple linear regression

analysis.

EXAMING POS AND JE 3

Acknowledgments

I owe a monumental thank you to my Chair, for guiding me throughout this

journey. Committee member, thank you for stepping in to join my committee at the last

minute, I greatly appreciate your contributions. I could not have asked for a better team.

Thank you, friends and family, for providing me with support throughout the

years. Special thanks to my mom for always checking in with me to see how I am doing,

ensuring that I stay motivated, and pushing me to be the best version of myself.

EXAMING POS AND JE 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................... 4

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 9

Background ........................................................................................................... 10

Problem Statement ................................................................................................ 12

Purpose of the Study ............................................................................................. 13

Research Question(s) and Hypotheses .................................................................. 14

Assumptions and Limitations of the Study ........................................................... 14

Theoretical Foundations of the Study ................................................................... 16

Definition of Terms............................................................................................... 18

Significance of the Study ...................................................................................... 19

Summary ............................................................................................................... 20

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW .......................................................................... 23

Description of Search Strategy ............................................................................. 24

Review of Literature ............................................................................................. 25

Biblical Foundations of the Study......................................................................... 50

Summary ............................................................................................................... 52

CHAPTER 3: RESEARCH METHOD ............................................................................ 53

Research Questions and Hypotheses .................................................................... 53

EXAMING POS AND JE 5

Research Design.................................................................................................... 54

Participants ............................................................................................................ 54

Study Procedures .................................................................................................. 56

Instrumentation and Measurement ........................................................................ 57

Operationalization of Variables ............................................................................ 58

Data Analysis ........................................................................................................ 58

Delimitations, Assumptions, and Limitations ....................................................... 59

Summary ............................................................................................................... 60

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS .................................................................................................. 62

Overview ............................................................................................................... 62

Descriptive Results ............................................................................................... 62

Study Findings ...................................................................................................... 63

Summary ............................................................................................................... 68

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION ............................................................................................ 69

Overview ............................................................................................................... 69

Summary of Findings ............................................................................................ 69

Discussion of Findings .......................................................................................... 70

Implications........................................................................................................... 72

Limitations ............................................................................................................ 76

EXAMING POS AND JE 6

Recommendations for Future Research ................................................................ 77

Summary ............................................................................................................... 80

REFERENCES ................................................................................................................. 82

APPENDIX A: SITE AUTHORIZATION .................................................................... 104

APPENDIX B: PERMISSION TO USE SURVEYS .................................................... 107

APPENDIX C: QUESTIONNAIRE .............................................................................. 109

APPENDIX D: PERMISSION RESPONSE DOCUMENT ......................................... 113

APPENDIX E: PERMISSION RESPONSE TEMPLATE ............................................ 114

APPENDIX F: FACEBOOK POST FOR DATA COLLECTION ................................ 115

EXAMING POS AND JE 7

List of Tables

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics …………………………………………………………... 63

Table 2 Model Summary ………………………………………………….……………...64

Table 3 ANOVA ………………………………………………………….………………64

Table 4 Coefficients …………………………………………………….………………..64

Table 5 Collinearity Statistics ……………………………………………………………67

Table 6 Turnover Rate Percentage ……………………………………………………...79

EXAMING POS AND JE 8

List of Figures

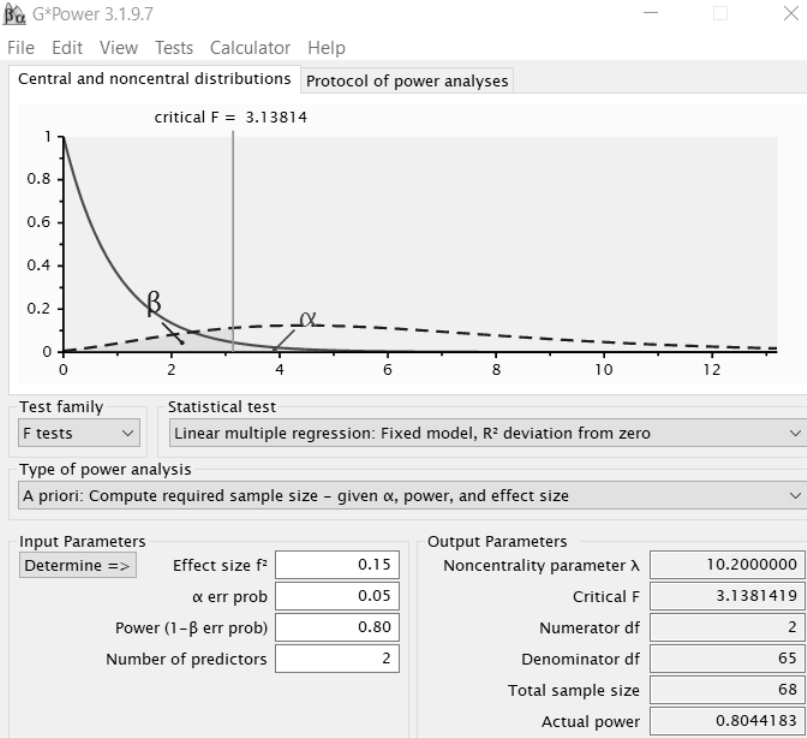

Figure 1 A Priori……………………………………………………………….…………56

Figure 2 Normal P-P Plot of Regression Standardized Residuals………….……………65

Figure 3 Normal Q-Q Plot of Normality for Turnover Intention ………………………..65

Figure 4 Scatterplot …………………………..………………………………………….66

Figure 5 Turnover Intention Scale Histogram …………………………………………...67

EXAMING POS AND JE 9

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Employee retention persists as a top priority in organizational research because of

the vast number of variables that impact it such as cultural shifts, motivational changes,

technological advancements, employees seeking meaningful work, and shared value

within the organization (Khairunisa & Muafi, 2022). Throughout this paper, retention

refers to what the business or industry experiences with people leaving, while turnover

intention is what the individual employee experiences when they consider leaving

(Cohen, 1999; Mobley et al., 1979). Furthermore, economic volatility changes the work

environment, causing the workplace to adapt and overcome these unforeseen obstacles

(Choy & Kamoche, 2020). When these variables are introduced to a work team, retention

remains important for all parties involved because the team relies on everyone’s

contribution to remain successful (Schulze & Krumm, 2017). Retention is a primary

focus to optimize the workforce, keep people embedded in their roles, and give

organizations tools to reduce turnover (Choy & Kamoche, 2020). This study investigated

the predictive relationship between perceived organizational support (POS) and job

embeddedness (JE) on turnover intention. POS has been used to predict employees’

intentions of quitting; when POS at an organization is low, employees will have higher

intentions of quitting (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Serban et al., 2021). The job attitude JE

was selected to assess how meaningful work, relationships, and job-fit impact retention

and POS. JE measures the overall fit that an individual employee has to the job and the

community (Ampofo & Karatepe, 2021; Sessa & Bowling, 2020).

How employees view their company’s support is influenced by a variety of

strategies that companies use to help retain their employees. For example, pay, non-

EXAMING POS AND JE 10

financial compensation, work schedule, talent acquisition, job placement, rapport,

supervisor relations, leadership training, professional development, and promotion paths

impact an employee’s level of POS (Serban et al., 2021). Focusing on the employee, JE

helps evaluate their belongingness in their job role and the myriad of relationships

created throughout the business and community, determining what an employee loses

when they leave a job (Thakur & Bhatnagar, 2017). Literature on leadership and

motivation was assessed to further explore the nature of POS and JE. Leadership is one of

the variables that contributes most to POS and motivation and has a great impact on a

person’s intentions of quitting (Zhou et al., 2022). Motivation is a powerful predictor of

JE and retention, while POS and leadership can be used to optimize employee motivation

(Ali & Anwar, 2021). Focusing on Generation Z (Gen Z) workers can lead companies to

optimization as the current workforce is comprised of nearly 25% of this age group

(Pichler et al., 2021). Gen Z’s are people that were born between 1997 and 2013. This

study contributes to the field of organizational study by assessing key variables that

impact retention and direction for future research.

Background

Retention is defined as the company’s ability to keep an individual employed over

a period of time, measured by an individual’s turnover intention (Cohen, 1999).

Retention has been a focal point for organizational researchers and business leaders since

the development of corporate structure and gained more popularity during the industrial

revolution (Sessa & Bowling, 2020). As factories and corporations expanded, the need

for employees increased and companies were forced to adopt hiring, training, and

retention plans to remain competitive within their respective markets (Hopson et al.,

EXAMING POS AND JE 11

2018). These plans remain critical for companies to maintain competitiveness today. In

today’s volatile market, retention is heavily impacted by the addition of new variables

such as remote initiatives, younger generations entering the workforce, or different

supervisor relations. According to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (2022), the leisure

and hospitality industry hosted over a 50% turnover rate in 2022. Ampofo and Karatepe

(2021) suggested that workers could be better retained by building stronger social

interactions within the workplace while Mashi et al. (2022) explain that organizational

rewards will keep people aligned (retained) with their hotel employer. Both studies

focused on hospitality businesses (hotel staff) and found various data and implications.

Studies have emerged on millennials in the workforce, explaining and

highlighting the differences in generations within a working environment. Nabawanuke

and Ekmekcioglu (2021) encourage companies to focus on work-life balance to maintain

team cohesion amongst age-differentiated employees. The younger employees might not

see eye-to-eye with the older generations because they have different work ethics, the

younger workers are more technologically inclined, and people mesh better with team

members closer in age (Hurtienne et al., 2021). Furthermore, there appears to be a

difference in motivational factors that cause people to leave a company, whereas younger

employees are more willing to leave. The importance of studying this younger

demographic of workers in a service-related job stems from the motivational shifts, to

help explain why they leave their company. Mahmoud et al. (2020) conducted a study on

the different motivations between millennials and older-generation workers and found

that millennials were more motivated by recognition and acceptance. This study focused

on the youngest generation of workers entering the leisure and hospitality industry to help

EXAMING POS AND JE 12

expand the knowledge on retention. This study aimed to understand the phenomenon of

retention; there are currently vastly divergent directions being suggested to the industry.

To minimize the spread of data, research must focus on a certain age group (King et al.,

2021). The 18- to 25-year-old demographic would provide sound data to assess why

younger employees are leaving the company. This age group requires attention because,

in January of 2022, the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (2022) reported the lowest median

tenure (2 years) was in the leisure and hospitality industry, where 19-year-old workers

had less than a 12-month tenure status. These workers hosted over a 50% turnover rate,

which was higher than all the other industries.

Problem Statement

It is not known what variable (POS or JE) best predicts retention in Generation Z

employees working in the leisure and hospitality industry. POS has been widely

researched in the business environment and has been shown to increase motivation and

employee longevity (Caesens et al., 2020), increase affective commitment and

psychological empowerment (Yogalakshmi & Suganthi, 2018), while increasing

innovative behavior and social exchange (Nazir et al., 2018). As POS explores the

employee’s perception of how the company looks after them, JE examines the wide range

of job and community variables that keep an employee retained (Dechawatanapaisal,

2018). There is a gap in the research on the level of prediction that POS and JE have on

retention, and both have been shown to be greatly valued by the Gen Z population

(Agrawal et al., 2022; Arici et al., 2023; Pramana et al., 2021). Previous studies have not

compared POS and JE side-by-side as predictors of retention in the leisure and hospitality

industry, specific to the Generation Z employees. This study was needed to showcase the

EXAMING POS AND JE 13

predictive weights of POS and JE on retention, giving business leaders and researchers

data on whether organizational support (POS) or job and community factors (JE) are

more important to the younger generation. For example, the analysis for this study is set

to identify which variable best predicts turnover intention, which could lead businesses to

improve those areas and ultimately better retain staff. The findings contribute to the

understanding of workplace dyads that lead people to quitting by highlighting the more

predictive variable (Huning et al., 2019), offering researchers a luminous direction for

future studies of retention. Jolly and Self (2020) recommend focusing on lower-level

employees, specific to the leisure and hospitality industry while King et al. (2021) add

that younger workers (age 18-25) should be examined to better understand their

perception of the company and why they leave a company. POS and JE require further

research because they are two main factors causing turnover in the younger generation,

and the Gen Z population is entering the workforce in full stride (Bryngelson & Cole,

2021).

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this quantitative correlational study is to examine the weight of

prediction that Perceived Organizational Support and Job Embeddedness have on

employee turnover intention. This study focused on employees who are 18 to 25 years

old working within the leisure and hospitality industry in America. This study aimed to

identify the level of prediction that POS and JE have on young adults' intentions of

quitting, specific to the leisure and hospitality industry.

EXAMING POS AND JE 14

Research Question(s) and Hypotheses

Research Questions

RQ1: Does perceived organizational support predict turnover intention in Gen Z

personnel working in the leisure and hospitality industry?

RQ 2: Does job embeddedness predict turnover intention in Gen Z personnel

working in the leisure and hospitality industry?

RQ 3: Between perceived organizational support and job embeddedness, which is

the stronger predictor of turnover intention in Gen Z personnel working in the leisure and

hospitality industry?

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1: Perceived organizational support predicts turnover intention in Gen

Z personnel working in the leisure and hospitality industry.

Hypothesis 2: Job embeddedness predicts turnover intention in Gen Z personnel

working in the leisure and hospitality industry.

Hypothesis 3: Perceived organizational support is the stronger predictor of

turnover intention in Gen Z personnel working in the leisure and hospitality industry.

Assumptions and Limitations of the Study

During data collection, it was assumed that the participants answered honestly

without any outside influence. This study relied on the participants to answer honestly

because it was structured to evaluate the individual’s perception of how they are treated

in their role at work. If they fear there will be repercussions if they answer a certain way,

the data may not be accurate. Participants were reminded that the data will not be shared

with employers and personal data will not be collected (name, job title, employer, etc.).

EXAMING POS AND JE 15

The study parameters were addressed and the participants were informed that their

honesty could potentially benefit future adults entering the workforce, and they were not

asked any identifiable questions to ensure their identity remains anonymous. There are

potential confounding items that could skew the data such as individuals who work for

companies that recently gave bonuses, new promotions, or the employee is relatively new

and has not yet established a relationship with supervisors. This study focused on their

current employer and did not account for previous work experiences. To combat this

potential limitation, this study was structured to evaluate the predictive impact of POS

and JE on retention within their current employment.

There are a few known limitations of the study design, industry, and target

audience. This study is a quantitative correlational design that assesses the relationship

between variables. Limitations exist because the research cannot further explore a

respondent’s answers to the question. This specific study was best assessed using the

quantitative design to obtain empirical, numerical data. The leisure and hospitality

industry has some potential limitations because the industry is broad. This study was

structured to benefit from the broad range (disseminating the survey to large service-

related groups) of companies that comprise the industry because generalizable data was a

priority. Within the industry, companies have a monumental difference in customer

volume, interaction, size, location, etc. Respondents may have answered the survey

differently depending on the volume of customers or other variables that impact

motivation on that given day. For example, a server who filled out the questionnaire on a

Monday versus a busy Saturday might have given different results.

EXAMING POS AND JE 16

This study benefited from the variety of respondents within this industry because

the aim was to achieve generalizable information for all industries. Focusing the research

and data collection on younger employees offered some limitations because they might

not have any other previous work experience, their maturity levels differ, or their

employment status (part-time vs. full-time) may vary. Despite the potential limitations,

this study offered the best results by obtaining a variety of participants throughout the

leisure and hospitality industry. It also provided empirical data on current organizational

variables that impact retention. This study relied on participants’ perceptions of their

company, relationships, and job fit to best acquire generalizable data to combat

worldwide retention issues.

Theoretical Foundations of the Study

This study focused on the predictive impact between perceived organizational

support (POS) and job embeddedness (JE) on retention. Blau’s (1964) social exchange

theory best explains the relationship between the individual employee and their employer.

In this theory, Blau (1964) explains that people’s reactions or involvement will be a

reciprocation of their surrounding social environment. In the presence of a workplace,

people will gauge their relationships based on what is reciprocated by other coworkers.

POS’s theory is founded by Eisenberger et al. (1986), which progresses the social

exchange theory by adding the thought that employee retention is directly impacted by

the perceived level of support they receive from their supervisor and company.

Furthermore, Eisenberger et al. (1986) explained that people will leave their company if

they feel their efforts are not matched, if they do not feel supported by the company, or if

their values are not the same as the company’s. Meaning, if the offerings of a company

EXAMING POS AND JE 17

are not equal to a person’s performance, or a perception of their performance, they will

not feel that their company values their efforts (Eisenberger et al., 1986). The

combination of both theories helps align the research to investigate the employee’s

anticipated recognition for completing a task. When the task is done, an employee might

feel that their efforts should be reciprocated (Blau, 1964), and expect that their supervisor

will show them gratitude (Eisenberger et al., 1986).

This study expanded upon what is known about the popular phenomenon of

retention. Deci and Ryan’s (2000) self-determination theory (SDT) focuses on the

employee’s motivation as derived from their leader’s intent. The three main pillars that

Deci and Ryan (2000) present are autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Autonomy is

established when supervisors trust their employees to carry out tasks; relatedness covers

the relationship between the leader and follower; and competence is the employee’s self-

assessment of their capabilities. If these three pillars are fulfilled, the worker will remain

motivated and ultimately retained. SDT pairs well with the social exchange and POS

theory because the relationship between the leader and the follower impacts one’s

motivation. This is important because this study aimed to specifically examine the weight

of POS and JE as predictors of retention. Both variables are greatly comprised of

leadership implications and the individual’s level of work motivation. Eisenberger et al.’s

(1986) POS theory, Blau’s (1964) social exchange theory, and Deci and Ryan’s (2000)

SDT best aligned this study to progress the understanding of variables that impact

retention in the contemporary workplace. The biblical perspective used to guide this

research stems from Wolters’ (2005) suggestion to seek out the truths in all things. This

EXAMING POS AND JE 18

study was designed to identify whether POS or JE is the stronger predictor of an

employee’s turnover intention.

Definition of Terms

The following is a list of definitions of terms that are used in this study.

Job Embeddedness – Job embeddedness (JE) is defined as an individual’s link, fit, and

sacrifice to their job and community. JE has two categories: on-the-job embeddedness

and off-the-job embeddedness. On-the-job explores the individuals’ relationships within

the workplace, fit to their job (knowledge, skills, abilities), fit to the social context of the

team, and what they would lose if they left the company (sacrifice). Off-the-job

embeddedness covers the individuals’ at-home life, their link to the community, friend

groups, social groups, community involvement, and what they would lose from leaving

that community (Burrows et al., 2022; Crossley et al., 2007; Fasbender et al., 2019; Sessa

& Bowling, 2020).

Perceived Organizational Support – Perceived organizational support (POS) is defined

as the individual’s perception of how their employers support them. Support is job

security, financial compensation, supervisor relationships, promotion path, clear goals,

fair treatment, and equal opportunity work environments (Eisenberger et al., 1986;

Eisenberger et al., 2014; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

Retention – Retention is defined as the company’s ability to keep an individual

employed over a period of time, measured by an individual’s turnover intention (Mobley

et al., 1979).

EXAMING POS AND JE 19

Turnover – Turnover refers to employees who quit their jobs and is defined as the

number of people who leave the company during a period of time (Omanwar & Agrawal,

2020).

Turnover Intention – Turnover intention refers to an employee’s willingness to leave a

job and is defined as an individual's level of intention of leaving their current

employment (Cohen, 1999).

Leadership – Leadership refers to a person of power within the workplace (e.g.,

manager, supervisor) and is defined as the act of engaging with individuals to motivate

them to achieve a common goal (Huning et al., 2019; Quek et al., 2021; Van

Dierendonck & Nuijeten, 2011).

Motivation – Motivation refers to the individual within the workplace and is defined as

the individual’s willingness to engage with others, the effort they put into their work, and

their workplace motivational needs (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Gagne et al., 2014).

Significance of the Study

This study contributed to society and future research by providing empirical data

on the perception of low-level employees within service-related jobs in the leisure and

hospitality industry. This study expanded upon the antecedent findings from Eisenberger

et al.’s (1986) POS theory by focusing on the employee’s perception of company support,

related to a specific job attitude (job embeddedness), at the lower level. Herr et al. (2019)

explain that when people feel more supported by their employer, they will become more

embedded in their role. This study highlighted the importance of organizational support

and ensuring that people have meaningful tasks to keep them retained. Blau’s (1964)

EXAMING POS AND JE 20

social exchange theory was expanded upon by examining the overall relationship

between employer and employee.

Business leaders can benefit from the findings by seeing what motivates the

younger workers and how they perceive the job and company. These findings can offer

predictor variables to measure future alignment. Furthermore, examining predictors of

retention will give companies insight into potentially effective leadership strategies, how

to retain the younger workforce, and solutions on how to optimize the workforce in the

service industry. Focusing on the leisure and hospitality industry maximized the findings

and contributions because this industry had the highest turnover rate in 2022 (U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). Akgunduz and Sanli (2017) found POS and JE to be

positively related to hotel employees, based in Turkey. Expanding on their findings and

answering their call to future research, this study obtained data on a larger basis of

hospitality-related industries. The American market categorizes the leisure and hospitality

industry into one entity (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). In such competitive

markets and diverse workforces, companies are required to remain adaptive, ensuring that

they are creating the best work environment for their employees (Ampofo & Karatepe,

2021). This study may pave the way to retention solutions related to younger employees

and contribute to organizational psychology literature. Furthermore, business leaders will

benefit from reading the results of this study because it provided insight into POS, JE,

and retention in their Generation Z workers.

Summary

Perceived organizational support and job embeddedness require additional

research to further examine retention, the strength of the prediction, and how businesses

EXAMING POS AND JE 21

can use these variables to create a better work environment (Jolly & Self, 2020). The

American leisure and hospitality industry is a massive industry with one of the highest

turnover rates (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022). Focusing on this industry provided

sound empirical data on retention issues, providing insight into how to reduce turnover

(Akgunduz & Sanli, 2017; Ponting & Dillette, 2020). Diversity is becoming more

relevant in the common workplace because people are becoming more open with their

sexuality, how they identify, and what sets them apart from others (Caesens et al., 2020).

This study evaluated the younger employees in the workforce, offering generalized

information on how people currently view their employer, what motivates them, and why

they are quitting their jobs.

There are many influences that impact a team’s outcome. In a workplace team

dynamic, outside factors such as economic shifts, customer motifs, or community

involvement impact how people perceive their organization and their motivation to work

(Choy & Kamoche, 2020). Internal factors such as leadership, promotion, job roles, and

relationships further drive people’s view of organizational support (Muhammad et al.,

2020). This study focused on retention through POS and JE because it covers both

internal and external factors that cause people to quit their jobs (Huning et al., 2019).

Leadership has a monumental impact on employee engagement, embeddedness,

perception of support, and retention (Hill et al., 2014; Quek et al., 2021; Wang et al.,

2022). Motivation is the driving factor in how people act within their role, how satisfied

they are at work, and if they will leave the company (Ali & Anwar, 2021; Deci & Ryan,

2000). Literature on leadership and motivation will be assessed to further explore what is

known about POS and JE. The overall intent is to progress what is known about retention

EXAMING POS AND JE 22

in organizational psychology while expanding on the theoretical frameworks of the social

exchange theory, SDT, and POS theory.

EXAMING POS AND JE 23

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

The modern workforce endures inevitable change as the economy cycles, social

normality shifts, technology advances, and new leaders emerge. Corporations are tasked

with adapting to these shifts to ensure their company remains profitable, competitive, and

valued (Saks, 2019). In such competitive markets, retention remains a top priority for

business leaders and researchers because workers have a plethora of job options (Kroll &

Tantardini, 2019). If an employee feels that they are not valued by their current employer,

they can seek job opportunities at direct competitor businesses (Choy & Kamoche, 2020).

With similar brands (e.g., McDonalds vs. Burger King), the employee will seek a job that

supports them financially, mentally, motivationally, and provides them with professional

growth (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Occupational research has focused on the interactions

between employees, supervisors, and the organization to further understand why people

leave a company (Blau, 1964; Hopson et al., 2018). It is important for companies to

retain their employees because it optimizes the workforce, creates consistency within the

team, reduces company spending on training new employees, and can increase the overall

performance of individuals and the company (Choy & Kamoche, 2020). This study aimed

to explore specific variables that impact retention in the contemporary workforce.

Increasing in popularity, perceived organizational support (POS) specifically

examines the employee’s perception of how they are supported by the company. When

POS is high, employees have a lower chance of leaving the company because they feel

that their efforts are appreciated (Eisenberger et al., 1986, 2014). The second variable of

interest is job embeddedness (JE). JE is a workplace attitude that measures a specific

individual’s relationship to their job and community (Sessa & Bowling, 2020). Literature

EXAMING POS AND JE 24

on the younger demographic will showcase the importance of adapting company policies

because generational differences impact job involvement (Thalgaspitiya, 2021). Chapter

2 covers the strategy used to obtain sources, what is currently known on the variables

selected for this study (POS, JE, and retention) in current organizational research, and the

biblical foundation for this study.

Description of Search Strategy

Research was primarily sourced through the Jerry Falwell online library at Liberty

University. Google Scholar was also used to source articles. The search terms utilized

throughout the course of research were job embeddedness, perceived organizational

support, retention, leadership and POS, motivation and POS, employee motivation and

retention, Gen Z, hospitality, used in a variety of combinations to maximize the relevancy

and quantity of results. For example, a search term would appear as follows: job

embeddedness and perceived organizational support, leadership, and perceived

organizational support. The two main variables POS and JE have many studies relating to

job satisfaction, and the priority of research was to find previously determined links

between the two variables (Yang et al., 2019). Within the database of the library, the

Mental Measurements Yearbook was used to assess the measurements used in studies and

to select measures for this study. Delimitations were set to ensure that articles were less

than three to five years old, except for antecedent or theory-based articles supporting the

study. Biblical research was aligned with the integrated approach which allows the

researcher to emulate the Lord’s character traits, while using scripture to explain the

relevance of biblical findings to the topic (Johnson, 2010). This research brought a

EXAMING POS AND JE 25

valuable explanation of the variables to society (Wolters, 2005). It also highlights

solutions to optimize people's time in the workplace.

Review of Literature

Previous literature has covered a variety of organizational phenomenon related to

retention. This section starts with an introduction to the generation under review, then

proceeds to the evolution of the workplace, how diversity has influenced change in the

workplace, how teamwork impacts retention, and the influence that leaders have. Next,

this section explains what is known about the variables selected for this study. It is

structured so that each variable is expanded upon individually and associated with the

other variables. For example, this section provides what is currently known about POS,

including the foundational factors of POS (leadership and motivation), and how POS is

impacting the Gen Z population and the leisure and hospitality industry. The literature

explains POS as an individual variable and the impact that it has on retention. JE is also

explained as an individual variable, the impact it has on retention, and the cohesion it has

with POS. Leadership and motivation are added to this section because they are some of

the largest contributing factors to POS, JE, and retention. This section was structured in

such a manner to showcase the similarities between the variables, and why it is important

to treat them as individual variables to further the understanding of retention.

Generation Z

Organizational psychology requires continuous research because different

variables are presented in the workforce and they need to be further explored to fully

understand the implications. In this case, the targeted phenomenon is retention. The new

wave of employees entering the workforce requires direct attention to further what is

EXAMING POS AND JE 26

known about retention. This generation is the Generation Z (Gen Z) population born

between 1997-2013 (Holly, 2019). There are core variables studied in organizational

psychology specific to retention, motivation (intrinsic, extrinsic, group, individual),

leadership (throughout the hierarchy of the business structure), employee relations

(varying by the size of the team and business), different generations entering the

workforce, etc. (Griffin et al., 2020). The workplace has drastically changed over the

years because of social media, demand, technology, and market competition (Satter,

2019). For example, remote work offered a new perspective for managers to maintain the

team’s integrity, create new policies to ensure that people remain motivated, and

showcase support by offering insight into employees’ work-life balance (Eddleston &

Mulki, 2017). The workplace was driven by technology, with the pandemic as a catalyst,

to adopt the remote initiative. Alongside technological advancements, the generation of

young adults entering the workforce were raised using these advancements and expect to

use them in their workplace. The above-mentioned Gen Z employees entering the

workforce require examination to help businesses adapt, lead coworkers to a better

understanding of how to work with this generation, and educate Gen Z about what to

expect when entering the workforce.

Generation Z in the Contemporary Workplace

As technology revolutionizes the workforce, the generation of workers born

alongside technological advancements will quickly adapt and optimize the workforce

(Ganguli et al., 2022). According to Bryngelson and Cole (2021), there could be nearly

60 million Gen Z personnel entering the workforce over the next decade. As this age

group enters the workforce, retention could be impacted because there is a

EXAMING POS AND JE 27

communication barrier between the generations, social interactions are different from

what the older generations are used to, and motivational drives differ throughout the team

(Khairunisa & Muafi, 2022; Mahmoud et al., 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2019). Miller (2018)

mentioned that this age group is having a difficult time integrating with the current

workplace because they lack social awareness, the in-person team dynamic is stressful to

them, and they are not as comfortable with public speaking. The leisure and hospitality

industry has one of the highest turnover rates comparatively (U.S. Bureau of Labor

Statistics, 2022); Gen Z workers are going to add to the retention issue or not join the

industry if they feel unwelcome (Bryngelson & Cole, 2021; Pramana et al., 2021). This

presents a monumental issue for the workforce because industries will have staffing

issues if the next generation of workers only enter tech-based industries.

Gen Z is the focus of this study because there is a lack of research on their

generation as they enter the workforce. This is because they have been in the workforce

for less than a decade. The drastic difference in the generations is highlighted in current

workplaces, making team cohesion and retention a recurring issue (Bryngelson & Cole,

2021). This generation currently faces issues with adapting to the current workforce.

They are having trouble conforming to older leadership styles and they are more prone to

leaving a company (Pramana et al., 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2019; Satter, 2019). Gen Z

employees have difficulty adapting for a variety of reasons. Reasons range from their

perception of organizational support to their overall view on environmental issues

(Pramana et al., 2021). Pramana et al. (2021) explains that Gen Z people have a high

concern for climate change and other societal issues, ultimately changing how they

perform at work. Their work performance, to include team cohesion, has become an issue

EXAMING POS AND JE 28

because they are more concerned with outside influences and will leave a company if

their opinion is not valued or supported (Bryngelson & Cole, 2021; Pramana et al., 2021).

Furthermore, Gen Z employees are not the easiest to lead because they are already

planning for their next job, they are impatient, and they do not have a tolerance for

inefficient technology within the company (Rodriguez et al., 2019). This presents an

issue on both the employee and employer side because without cohesion, both parties will

not value each other’s opinions, trust will not exist, and companies will refrain from

promoting them (Deepika & Chitranshi, 2021). Without a promotion path, these younger

employees will immediately leave the company and find employment elsewhere

(Agrawal et al., 2022; Rodriguez et al., 2019). Gen Z employees are facing cohesion

issues within the work environment because they are not fully understood.

A generation raised on technology will have different perceptions of

organizational support, have alternate ways of becoming embedded with their roles,

motivational needs may vary, and the leadership required to keep them retained is not the

same as other generations. The workplace continues to have Gen Z employees entering

and changing the team dynamic. Kortsch et al. (2022) explain that organizations can

think outside of the box to help employees adapt to change, incentivize them, and create

happiness in the new structure. During these changes to the workplace, there are

companies that thrive, while other companies are unable to adapt. Through the different

generations that comprise the workforce, there can be a communication gap because there

are various preferences in the communication channels (Agrawal et al., 2022). Gen Z

workers are now entering the workforce and being forced to adapt to corporate standards.

This is drastically different from the Gen Z normality because they were born and raised

EXAMING POS AND JE 29

in a social media boom, making them more comfortable communicating through a screen

rather than face-to-face interactions (Schroth, 2019). A workplace with a communication

barrier will have productivity halted, ultimately contributing to turnover (Khairunisa &

Muafi, 2022). The younger generations that enter the workforce drastically differ from

the more senior workers and require different approaches to keep them retained

(Hurtienne et al., 2021). Research will remain necessary to help describe and understand

phenomenon that causes retention numbers to fluctuate. The purpose of the next three

sections (diversity, teamwork, and influence) is to show what common workplaces

endure and how the gen Z population requires additional research.

Diversity

Over the years, diversity has become a more common topic in the contemporary

workplace because people are more open with their sexuality, race, and how they identify

(Cancela et al., 2022). Additionally, the newest generation of employees (Gen Z) are

diverse in their own way due to the availability of technology throughout their childhood,

their concern with the environment, and their approach to problem solving (Pramana et

al., 2021). Diversity comes in a variety of forms, all requiring different strategies to

optimize the potential outcome. Hurtienne et al. (2021) found that younger generations

require a different approach to maintaining work engagement; companies can no longer

conduct a mass hiring and expect Gen Z workers to feel supported and motivated to

work. Agrawal et al. (2022) conducted a study on the different generations within a

workforce and found a great difference in retention based on employee’s level of job

embeddedness. Diversity is a monumental factor in the workplace because people

gravitate toward similar individuals in social groups (Tajfel, 1978). Ng and Sears (2018)

EXAMING POS AND JE 30

found that companies must fulfill two portions of diversity initiatives: clear policies set in

play and following up with the policies making people feel comfortable in their roles.

Meaning, companies cannot just market that they are an equal opportunity workplace,

they must follow through with their policies and create a positive diversity climate that

makes everyone feel welcome (Jolly & Self, 2020). To generalize diversity in the

workplace, companies must show their support to all their employees, ensure they give

individuals a voice, and properly assign people to a role that optimizes their knowledge,

skills, and abilities (Cancela et al., 2022).

Teamwork

Businesses seek to reach the highest level of performance, remain competitive

within their industry, and maximize profits. As work teams become more diverse, there

could be a potential for friction points within the staff, leading to an overall decrease in

the company’s efficiency (Saks, 2019). To remain competitive, companies must properly

assess their employees and put them in a role where they will succeed (Ju et al., 2021).

Wu and Wu (2019) explain the importance of employee engagement to increase

innovative behaviors. Employees who are not in their preferred role might only act

friendly and cordial to their peers to get through the day. If the person was engaged, had

fulfilling work, and wanted to be there, healthy professional relationships would form and

optimize the team’s work (Smith et al., 2021; Wu & Wu, 2019). When a team gains a

new member or an outside force influences change, the team endures a cycle of

adaptation (Tuckman, 1965). As the new generation with diverse traits and qualities

enters the workforce, organizations will restart the cycle of team building. Tuckman’s

(1965) theory on team development supports the need for future research in

EXAMING POS AND JE 31

organizational psychology on retention, how people fit within their roles, and how the

company can provide for their employees. Cho et al. (2018) discuss the importance of

employees seeking to fit in with social groups and the Gen Z workers using social media

to fulfill their motivational needs. This makes their at-work life different than other

workers because they might be more attracted to their phones, seek social networking

engagement over in-person engagement, and they perceive interactions differently than

other generations of workers (Wood et al., 2022). Furthermore, the social exchange

theory does not evaluate the impact of the job that people hold in their organization.

Influence

There are many influences that impact retention in the workplace inside and

outside of the company’s physical infrastructure. Internal influences are things like

leadership, size of the company, organizational support, funding, pay, promotion paths,

etc. External influences are economic changes, market shifts, competitor performance,

target audience, etc. Focusing on internal influences can increase the company’s

resilience, ensuring that the team can handle any outside change (Duchek, 2020).

Everyone within a workplace adds a different perspective, thought process, and benefit to

the team. Companies must understand their workers by building rapport, properly

aligning their goals, using different leadership styles to motivate younger workers, and

putting them in positions that will play to their strengths (Deepika & Chitranshi, 2021).

Choy and Kamoche (2020) identified destabilizing factors such as employee relations, the

work environment, and the hours (night shift vs. day shift) that people work greatly

contributes to turnover intentions. These facets are influenced by business owners and

managers; they have the power to create a work environment that retains people.

EXAMING POS AND JE 32

Influence will become more important as the Gen Z population consumes the workforce

because they will seek out mentorship (Loring & Wang, 2022). Relationships are

mandatory throughout the hierarchy of the business to properly assess what motivates and

influences people to stay aligned with the company (Dechawatanapaisal, 2018; Deci &

Ryan, 1985; Eisenberger et al., 1986).

Perceived Organizational Support

Perceived organizational support (POS) is the employees’ perception on how the

company supports them, including leadership interaction and organizational commitment

(Tremblay et al., 2019). POS stems from the organizational support theory, which

explains that employees expect reciprocated effort from their employer (Eisenberger et

al., 1986). Employees want to know that their efforts and contributions to the company

are valued and compensated. POS has been found to increase employee alignment,

morale, job satisfaction, and can optimize the overall performance of the team while

predicting retention (Muhammad et al., 2020; Traeger et al., 2022). Factors involved with

POS include the culture created in the workplace, the type of leader, training received,

individuals on the team, and the industry. Culture hosts a high level of importance in the

contemporary workplace due to the vast number of direct competitors (Nazir et al., 2018).

When the barrier to entry is low (minimal requirements to obtain a job within a certain

field), job seekers can shop around and search for a job that satisfies their needs. The

culture of a company is an intangible value created by POS that keeps people motivated

and retained (Guo et al., 2020). In competitive markets, individuals seek the best offer on

paper but will stay with a company longer if they feel supported by their employer.

EXAMING POS AND JE 33

Reciprocated value can be difficult to measure when job roles overlap, standards

are unclear, or cohesion is lackluster. Overlapping job roles can be confusing in the

workplace because an individual might expect to receive recognition for completing a

task, but the supervisor does not know who completed that specific task. When job roles

are defined and the standard is clear, supervisors can adequately showcase their

appreciation. Nazir et al. (2018) found that when companies provide support to their

employees, they show innovative behavior which can lead to higher profits. The

supervisor is a key factor in the POS equation because they have a direct relationship

with the owners and the lower-level employees. It is their job to be a role model, ensure

the culture matches the owner’s intent, and keep the lower-level employees motivated

and retained. Yang et al. (2020) explained that some workers thrive under organizational

support by assisting them with achieving their goals, while other types of employees use

organizational support to keep them aligned with the company’s values. POS has been

shown to predict employee’s intention of leaving a company, making it a high priority for

managers to understand (Arasanmi & Krishna, 2019). It is crucial that employers and

managers provide support and opportunity for their staff to stay retained.

Leadership in Perceived Organizational Support

The impact of leadership on POS is tremendous because the leader is a direct

representation of the organization and has a monumental impact on turnover (Eisenberger

et al., 1986; Quek et al., 2021). Evaluating the literature on leadership was mandatory for

this study to fully understand POS and the impact it has on Gen Z in the leisure and

hospitality industry. Leaders’ actions in the workplace dictate the perception that

employees have about the company (Serban et al., 2021). When leaders establish

EXAMING POS AND JE 34

professional relationships, Yogalakshmi and Suganthi (2018) found that leadership can

provide employees with tools for optimizing their future success. These tools are mental

frameworks that include believing in oneself (self-efficacy), knowing what good

leadership is, providing a resource, and helping establish cohesion in the team

(Yogalakshmi & Suganthi, 2018). For leaders that can create cohesion at the team level,

motivation will increase and production will rise (Everett, 2021). Tremblay et al. (2019)

found that group-level POS establishes more supportive behaviors for the staff to

reciprocate and can create a sound culture. Furthermore, when employees at all levels, to

include the younger generations, feel that their leader has their best interest in mind, they

will be more engaged at work and feel supported (Kolodinsky et al., 2018). Eisenberger

et al. (2014) proposed a link between POS and leader-member exchange (LMX), where

POS and LMX are positively related. Gaudet and Tremblay (2017) explain that

leadership styles that focus on initiating structure cause higher POS levels within their

followers. When leaders support their staff and establish a positive relationship, the staff

members will feel their organization supports them.

Considerations of Leadership on Generation Z

Assessing leaders for promotion is a difficult task that companies endure.

Companies typically promote employees who have been with the company for an

extended period because they have shown their potential, loyalty, matched interest, and

have learned the core values of the company (Hoff et al., 2020). These leaders tend to be

in their later years of employment, meaning they can range from 30 to 50-plus years old.

That specific age group (30-50+ years old) covers two different generations that are

currently in the workforce (adding Gen Z to the workforce makes three different

EXAMING POS AND JE 35

generations). When these leaders are tasked with adapting to the newest trends of

workers, they are forced to use different methods to lead. For example, an entrepreneurial

leader might have an innovative mindset to motivate the team, but the Gen Z employee

might be looking for a more directly supportive leader (Weerarathne et al., 2023; Yang et

al., 2019). Within the potential age gap in a workplace, there could be 55-year-old boss

with an 18-year-old employee. The older generation that is still in the workforce (Gen X)

values outcome, results, and people that work well with them while the Gen Z employee

might be more focused on their individual performance (Waworuntu et al., 2022). There

are contradicting suggestions when it comes to leading the Gen Z population because

Waworuntu et al. (2022) suggest fringe benefits or other extrinsic rewards while

Rodriguez et al. (2019) suggests a promotion path and creating autonomy to retain these

individuals. Future research needs further exploration of which best practices can be used

to lead the diverse generation of young workers.

To optimize retention, the Gen Z population prefers that companies focus on

inclusion and diversity, transparent company values, and leaders who take the time to

explain their positioning (Sherman & Cohn, 2022). A leader’s job can be difficult when

their team is not cohesive. Gabrielova and Buchko (2021) explain that Gen Z workers

require a different approach because they typically have poor interpersonal skills, lack

social awareness, and the leader to member relationship must be more transformative

versus transactional. Nabawanuke and Ekmekcioglu (2021) elaborate on the importance

of identifying age groups because the younger workers could be uncomfortable with in-

person interactions, while the older employees prefer it. Leaders will face new challenges

with the Gen Z population because they will have to become knowledgeable on the

EXAMING POS AND JE 36

technology, empower the younger workers by giving them remote work, and create a

culture that allows the Gen Z employee to flourish (Satter, 2019). Rodriguez et al. (2019)

recommends leaders should empower Gen Z workers when it comes to technology

because it will increase their team cohesion while combating their urge to leave the

company. Meaning, this generation entering the workforce does not have patience for

outdated technology (Rodriguez et al., 2019). Without flexibility, adaptation, and

emotional intelligence, leaders will struggle with creating a positive work environment

for the newcoming Gen Z staff, which could diminish employee engagement and

retention (Rasool et al., 2021). Gen Z workers entering the workforce will challenge

leaders to adapt to Gen Z needs, understand Gen Z perception, and deploy different

motivation strategies.

Progressing Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Deci and Ryan’s (2000) self-

determination theory (SDT) explains the implications of an individual’s work motivation.

Understanding employee motivation is mandatory to help predict their behavior,

performance, job satisfaction, perception of support, and their retention potential

(Mahmoud et al., 2020). Leaders must build rapport with their followers to gain insight

into what motivates them. Wang et al. (2021) found that leaders who express their goals

and interests help align their employees, creating more committed members who have

higher levels of motivation. When employees are motivated, they are more likely to stay

with a company (Shuck et al., 2021). Of all the leadership styles, some reduce

performance and increase intentions of quitting. Authoritarian leadership has a negative

impact on work outcomes, makes people feel less embedded in their job, and can hinder

their performance (Siddique et al., 2020). In a diverse workplace, leaders must ensure

EXAMING POS AND JE 37

their leadership style is effective, cohesive with the individual’s learning style, and

appropriate to match employees’ motivational needs. For example, Cho et al. (2018)

explain that Gen Z workers prioritize social media more than other generations, making

the workplace communication standard different than what people are used to. When

leaders have a negative strategy, the perception of support will be diminished and people

will seek employment elsewhere (Eisenberger et al., 2014)

Leadership styles that increase POS and JE take the approach of getting to know

their employee, finding out what motivates them, and putting them in a role where they

can succeed (Dechawatanapaisal, 2018; Kolodinsky et al., 2018). Using transformational

leadership as an example, studies have shown that leadership can directly impact an

employee’s level of motivation, support, and performance (Rachmawati et al., 2021).

Balwant et al. (2020) further explain that transformational leadership is best when job

resources and information is available to all employees, making them extremely

motivated at work. Furthermore, Aydogmud et al. (2019) add that when employees

perceive their leader as transformational, they become more motivated and satisfied with

their work. Gomes et al. (2022) suggest that a positive leader is responsible, emulates a

positive role model for employees and stakeholders, and can engage with all levels of

employees. An engaging leader will be able to create cohesion in the workplace, motivate

employees, increase their perception of support, and keep employees retained (Nikolova

et al., 2019). Leadership and the various styles help define POS and turnover intention.

Perceived Organizational Support in Generation Z

Employees’ perceptions of their organizations’ support can be drastically different

throughout the generations that comprise the team. For example, a Gen Z employee and a

EXAMING POS AND JE 38

Gen X employee will not want the same benefits package because they have different

needs (Baldonado, 2018). Gen Z needs differ from the other generations because they

sometimes rely on social media engagement over personal interactions, making their

workplace interactions fragile (Pramana et al., 2021). Pramana et al. (2021) further

explain that Gen Z employees have drastically different perceptions of their company and

supervisor depending on things like green initiatives, social media use, and technology

available in the workplace. The basic principles of POS still apply to all generations, the

only change is that the type of support will have to remain flexible depending on the

employee’s age (Andini & Parahyanti, 2019). In the leisure and hospitality industry,

employees typically work together. Pichler et al. (2021) found that Gen Z employees

have higher anxiety levels when working in groups compared to the other generations.

This can lead to a negative perception of the company if Gen Z workers are forced to

work in groups. A company reliant on group projects will have to restructure its support

system to ensure that the Gen Z employees stay retained. Additionally, Loring and Wang

(2022) revealed that Gen Z workers might appear as individualistic, but they seek

mentorship and support from their supervisor and company. Gen Z perceptions of their

organization drastically differ from the older generations. There is minimal research on

POS and the Gen Z demographic.

Perceived Organizational Support in the Leisure and Hospitality Industry

Akgunduz and Sanli (2017) found POS and JE to be positively related in hotel

employees, based in Turkey. In their study, they mention that future research should

continue to explore participants within this work domain to better understand employee

perceptions. Furthermore, their study greatly supported that POS can be increased by

EXAMING POS AND JE 39

information sharing, which increases JE, ultimately decreasing turnover intention

(Akgunduz & Sanli, 2017). Managers can assume that creating sound POS and JE

policies will predict an employee’s intention of leaving their company. When POS and JE

levels are high, managers can expect lower levels of turnover. Ebrahimi & Fathi (2022)

examined hospital nurses and found that POS led them to being more embedded in their

roles, which ultimately kept them retained. Ponting and Dillette (2020) explained that

luxury hotel staff in Mexico feel that their organizations support them when there is a

mutual level of respect from managers or a family-type bond; too many rules decreased

authentic relationships. Indian hospital staff prefer a leader that goes out of their way to

assist them; it makes them feel that their organization truly values their contribution

(Omanwar & Agrawal, 2020). Goh and Lee’s (2018) study further explains that there is a

lack of research covering Gen Z's perceptions of working in the hospitality industry. The

purpose of this paragraph is to showcase the wide range of global research on POS in the

leisure and hospitality industry. It is evident that there is a lack of research on the

predicted impact of POS and JE on retention, especially in the American leisure and

hospitality industry.

Job Embeddedness

According to Sessa and Bowling (2020), job embeddedness (JE) is a myriad of

forces that influences an employee’s decision to stay with their company. Furthermore,

JE is a workplace attitude that covers a person’s fit, link, and sacrifices made in their role

at work. Fit covers individuals’ cohesion with their workplace and their community

(Sessa & Bowling, 2020). Link for JE involves individuals’ relationships built in their

work setting and their at-home life (Smith et al., 2021). This understudied phenomenon is

EXAMING POS AND JE 40

divided into two categories that best assess intentions of quitting: on-the-job (OTJ) and

off-the-job (OFJ) (Sessa & Bowling, 2020). OTJ embeddedness covers the target’s

relationships built with other staff members, how they integrate with the team (cohesion),

and what they would do if they were to quit their job. OTJ embeddedness leads to higher

levels of retention because an employee’s link to the job is strong, making them

emotionally attached and less likely to leave (Burrows et al., 2022). Sessa and Bowling

(2020) explain that links associated with OTJ embeddedness are autonomy, fulfilling

work, clear standards, and challenging tasks that keep workers engaged. JE should be

further examined and taught to business leaders so they can understand the importance of

job fit to optimize their employees’ job performance and satisfaction.

OFJ embeddedness addresses work-life balance, community involvement and

support, and the social support system created outside of work. Using the same three

pillars, organizations can assess an employee’s retention potential through their fit, links,

and sacrifice outside of work (Sessa & Bowling, 2020). When people mesh well with

their community, they are involved with things outside of work, have family in the

geographical area, and have larger friend groups outside of work. They will have higher

retention potential because they will not want to lose those connections (Thakur &

Bhatnagar, 2017). Business leaders must be educated on JE to help retain employees,

create a better workplace for them, and give them the tools they need to be successful

outside of work. Smith et al. (2021) explained the importance of identifying employees

who have higher levels of JE because of their potential job performance, alignment,

commitment to the organization, and pride in their work. When people enjoy their time at

work and have meaningful tasks, their workplace well-being is infectious and can lower

EXAMING POS AND JE 41

people’s intentions of quitting (Khairunisa & Muafi, 2022). JE is a workplace

characteristic that can be used to assess individuals’ likelihood of leaving the company

outside of what POS measures.

Job Embeddedness and Perceived Organizational Support

Eisenberger et al.’s (1986) findings on employee perception showed that

employees are more engaged with their work when they feel their company values their

efforts. There are limited studies that focus on the relationship between POS and JE. Both

workplace constructs evaluate two main players in the workplace, the perception of the

organization and the employee (Eisenberger et al., 1986; Nazir et al., 2018). These

constructs directly relate to an employee’s intentions of quitting and should be examined

together to further develop retention strategies. Akgunduz and Sanli (2017) found that

POS is positively related to JE in hotel staff members. In support, Ebrahimi and Fathi

(2022) found that JE is a positive moderating variable to POS and job crafting. When

people are embedded in their job, POS can help optimize their performance by providing

them with an opportunity to display their true potential. Meaning, a company that

supports its employees will assess their knowledge, skills, and abilities (job crafting) to

properly fit them within the organization (Ebrahimi & Fathi, 2022). Separately, these two

variables have been shown to predict intentions of quitting. There are no current studies

that address which of the two variables is the stronger predictor in the leisure and

hospitality industry.

Work Motivation from Job Embeddedness

Employee motivations shift throughout the duration of their employment.

Consistent examination is mandatory to ensure that employees stay embedded in their

EXAMING POS AND JE 42

roles. JE is an important variable to examine for motivation because it covers both the job

and home traits of a target employee. These traits endure shifts in motivation for various

reasons. Further dissecting levels of motivation will help researchers and managers

predict intentions of quitting (Lyu & Zhu, 2019). Motivational theories separate

employees into two categories: intrinsic and extrinsic. Individual workers hold different

motivations; understanding their level of JE can help managers identify motivational

needs (Lyu & Zhu, 2019). When organizational JE is high, managers will be motivated

and take more responsibility for their worker’s performance (Mashi et al., 2022). The

culture of the workplace is extremely important. When people have defined roles and

empowerment, they will remain motivated at work (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Work

motivation will consistently shift as new variables are introduced to the workforce. These

shifts can impact an individual’s level of motivation, altering their overall level of JE and

potentially causing them to leave a company.

Job Embeddedness in Generation Z

Agrawal et al. (2022) found that Gen Z workers were less likely to leave a

company if they had a positive link to their organization. The leisure and hospitality

industry may have difficulty retaining Gen Z employees because they would rather work

in the tech industry (Rodriguez et al., 2021). Meaning, it would be more difficult for a

Gen Z worker to become embedded in their role at work if they prefer a completely

different job. To ensure that employees stay embedded in their roles, incentives packages

should be flexible so employees could benefit from alternate packages depending on what

age group they belong to (Deepika & Chitranshi, 2021). To assist with enhancing

employee relationships in the workplace, Akkermans et al. (2019) recommend that

EXAMING POS AND JE 43

companies should focus on their human resources initiatives. Hassan et al. (2022) explain

that different age groups in the workplace can be influenced through various rewards and

incentives, which ultimately increased their levels of job embeddedness while other

studies suggest that Gen Z employees just want meaningful work (Popaitoon, 2022).

Younger workers’ link to their company was strengthened when they received an

increase in pay (Hassan et al., 2021). Understanding the difference in employee age

groups will assist companies in creating initiatives that keep people embedded in their

roles.

It is extremely important for companies to identify employees’ motivational

needs so they can properly align them to a role, increase their JE, reduce the chance of

them feeling discriminated against at work, and give them purpose (White et al., 2022).

To ensure that people feel comfortable at work, social dynamics should be considered.

Aziz et al. (2021) explain that the work environment can be enhanced through clear

expectations, sound leadership, and using a communication style that everyone supports.

When the work environment promotes productivity, people will automatically become

more embedded in their roles and trust that everyone is pulling their own weight (Smith

et al., 2021). JE is an important variable to study within the Gen Z population because

they truly care about their community and the environment (Pramana et al., 2021). If the

workplace promotes good habits that benefit the surrounding community, current global

issues, and social trends, the Gen Z demographic will become more embedded in their

job (Agrawal et al., 2022). There is a need for future research in this age group on JE to

further what is known on the fit, links, and sacrifices that employees create in their lives.

EXAMING POS AND JE 44

Mahmoud et al. (2020) explain that people born in different generations will have

alternate means of motivation. People who were born alongside the technological

revolution may have extremely different motivators than a person who was born in an

earlier generation. For example, Mahmoud et al. (2020) found that millennials are

motivated by recognition and praise while Baldonado (2018) found that Gen Z employees

are demotivated by recognition. Baldonado (2018) stated that Gen Z workers are highly

motivated with promotion path opportunities. Additionally, Graczyk-Kucharska (2019)

explains that Gen Z employees might have increased motivation when assigned tasks that

involve technology use. This age group prefers delicate leadership and motivation styles

because they seek promotion paths but will also require social guidance, support in

mental health, eco-friendly initiatives and finding work that they thrive in (Gabrielova &

Buchko, 2021; Pramana et al., 2021). Holly (2019) further explored Gen Z in the

workplace, stating that they are fearful, are prone to blaming others for their mistakes,

and are also motivated by other employee’s achievements. There is a broad range of

things that motivate the Gen Z population. It will take specific leadership and cultural

actions to optimize their success in the work environment (Goh & Lee, 2018).

A population that can be motivated through the technology and empowerment of

the company adds a new method of creating team cohesion (Graczyk-Kucharska, 2019).

With technology comes the new social media networks that have taken over the

marketing industry. This impacts Gen Z’s motivation and levels of embeddedness in the

workplace because they are starting to feel pressure from companies. Companies are

targeting young adults using highly visual advertisements via social media to attract and

sell their products to the Gen Z population (Jacobsen & Barnes, 2020). Never has a

EXAMING POS AND JE 45

demographic been targeted in this manner, making their social media engagement

extremely difficult to understand. A generation of workers that specifically uses social

media as their primary means of communication also finds strain in their usage, making

each individual Gen Z employee unique in where their motivational level exists.

Meaning, a Gen Z employee that is finding pressure in their social media usage, can have

diminished self-determination (Herriman et al., 2023). Deci and Ryan (2000) explain that

self-determination is a root function of an employee’s motivation, where motivation

impacts level of JE and turnover intention. Herriman et al. (2023) expanded on their