39

The Word Intelligibility by Picture Identication (WIPI) Test Revisited

The Word Intelligibility by Picture Identication (WIPI) Test Revisited

Kathleen M. Cienkowski, PhD

Mark Ross, PhD

Jay Lerman, PhD

University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut

The Word Intelligibility by Picture Identication (WIPI) test is a widely used test to assess speech recognition for

pediatric clients. Since the test was developed over 30 years ago, a number of the pictures are outdated and several

test items have been reported to be unrecognizable by children today. The purpose of this study was to evaluate a

revised version of the WIPI. The test included modernized items and eliminated pictorial confusions. The result was

four revised lists found to be equivalent for a group of children with normal hearing.

Introduction

The assessment of speech intelligibility in children has long

represented a challenge to clinicians (Madell, 1998). To ensure

an accurate evaluation, the speech material must be within the

receptive vocabulary of the child, the response mode must be age-

appropriate, and the utilization of reinforcers may be necessary.

Even with care, test results may partially reect the child’s level

of interest and motivation (Northern & Downs, 2002). Although

many speech tests are available (e.g., Northwestern University

of Children’s Perception of Speech [NU-CHIPS]; [Katz & Elliot,

1978]; Pediatric Speech Intelligibility test [Jerger & Jerger,

1982]; Early Speech Perception test [ESP]; [Geers & Moog,

1990]), there is no generally accepted standard test for the speech

assessment of young children. The Word Intelligibility by Picture

Identication (WIPI) test developed by Ross and Lerman (1970)

remains among the most widely used tools for pediatric word

recognition assessment (Martin & Gravel, 1989; Stewart, 2003).

The test consists of four 25-item word lists with a vocabulary that

is appropriate for preschool children. The child responds to each

item by pointing to one of six pictures on a page, one being the test

item. Two items on each plate are foils. A recorded version of the

test is available, although most clinicians prefer monitored live-

voice presentation (Martin & Clark, 1996). The test is reported to

have good test/retest reliability, it is quick and easy to administer,

and analysis of incorrect responses can provide information on

auditory confusion (Ross & Lerman, 1970).

Since the test was developed in the late 1960s, a number of

the pictures are outdated and several test items have been reported

to be unrecognizable by children today (Stewart, 2003). Some

examples of outdated items include pictures of an oscillating fan,

an ink well, and a skeleton key. In addition, some test pages contain

inadvertent sources of confusion. For example, the clinician may

say to the child, “Show me door.” The child points to the picture of

the foil “house.” However the picture of the house includes a door;

consequently it is unclear whether the child got the item wrong or

simply pointed to a viable alternative. Work by Sanderson-Leepa

and Rintelmann (1976) and Dengerink and Bean (1988) reported

on some of these confusions made by children with normal hearing.

More recently, Stewart (2003) reported survey results on the use of

the WIPI test among practicing pediatric audiologists. She noted

that the WIPI was the test of choice for assessing pediatric speech

understanding among respondents in her sample. However, for

those respondents who did not select the WIPI as the test of choice

(43% of her sample), specic concerns were cited with the test

including “outdated items,” “pictures unfamiliar to children,” and

“don’t like the pictures.” She also noted that practicing clinicians

reported modifying the test during administration; specically

clinicians reported omitting or substituting test items.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate an updated version

of the test. Specically, the goals were to modernize test items as

needed and eliminate pictorial confusions while maintaining the

validity of the test measure.

Method

Preliminary Evaluation

The original WIPI stimulus words were selected from

vocabulary in children’s books and word-count lists. Items selected

were simple monosyllabic words that could be easily represented

pictorially (Ross & Lerman, 1970). To determine which items

represented words and pictures that may no longer be recognizable

by young children and/or may be confused with foils based on

the pictures, a group of 3 audiologists and 2 speech-language

pathologists working with young children were consulted as

knowledgeable experts. The expert group was asked to review each

item for its familiarity to young children and its pictorial clarity.

The authors evaluated those items that were deemed questionable

by the expert group to determine whether a change was warranted.

40

Journal of Educational Audiology vol. 15, 2009

The authors were in agreement with the expert group for all but two

suggested changes. The two items in question were “match” and

“gun.” The speech-language pathologists in the expert group noted

that “match” is an often-missed item on articulation tests. However,

the audiologists in the expert group did not report this item to be

frequently missed when administering the WIPI; therefore, the

authors elected to keep this item. The expert group also noted that

using “gun” as a test item was not in keeping with current social

convention toward non-violence. The authors disagreed with this

argument on the basis that the item is easily recognizable by young

children and the picture of the item does not endorse its use.

Table 1 shows the original WIPI test items. Items in boldface

represent those deemed questionable by the expert group and the

authors. Only one item as drawn (“ink well”) was thought unlikely

to be within the vocabulary of contemporary children. Although

this item is not a test item, it was changed to “sink” to make it a

more recognizable foil for this generation of children. One item

as drawn (“neck”) was thought to be too abstract. It was replaced

with “egg,” a foil from the same page. It was thought to be the

best alternative item to test, but it must be acknowledged that,

depending on pronunciation, this may alter the phonemic balance

of the list. All other changes were updates to more modern pictures

(13 items) and/or the elimination of confusing pictures (11 items)

as determined by the panel of experts. A local artist drew the

new pictorial representations of the test items to be changed after

consultation with the authors. After author review, pictures that

were confusing, unclear, or poorly drawn were redrawn.

Participants. Twenty children (10 boys and 10 girls)

with normal hearing ranging in age from 2.5 to 8.0 years

(Mean age: 4.5; S.D: 1.5) participated in the preliminary

evaluation. No participants were currently receiving speech and/

or language therapy as noted by parent report. All of the children

received a hearing evaluation prior to participation. Hearing

thresholds were measured at the octave intervals between 250 and

8000 Hz bilaterally using a portable audiometer (Beltone Model

119) in a double walled sound-treated booth. Play audiometry was

utilized for younger participants. Hearing was considered normal

if thresholds at all test frequencies were better than 20 dB HL

bilaterally (ANSI, 1989).

Test procedures. The four test lists were presented at

average conversational level in a face-to-face condition outside

a soundbooth. The examiner used a mesh screen to block the

child’s view of her mouth during presentations. The order of list

presentation was randomly assigned. All test items were presented

with a carrier phrase (“Show me...”). The examiner turned the

pages as the child made a selection. Play audiometry (e.g. putting

pieces in a puzzle), along with a social reinforcement, such as a

smile or hand clapping, were utilized to keep younger participants

interested in the task. Each participant was given verbal instructions

and/or a visual demonstration of the task by the examiner pointing

to a picture as she heard a word. A practice item was presented

prior to testing to ensure that each child understood the task. Each

of the six pictures was assigned a number from 1 to 6, with number

1 in the upper left hand corner and number 6 in the lower right

hand corner. The examiner scored each test item by marking down

the number associated with the child’s selection. This allowed the

examiner to track the number of correct responses, as well as the

errors, made. After all 100 test items were presented, the examiner

asked the child to name all pictures that were missed in the rst

presentation. The purpose of this was to determine whether the test

item was within the receptive vocabulary of the child and whether

the picture was a good representation of the item.

Results. Table 2 shows the mean percentage of items correct

and standard deviation by list. While the percentage of items

correct exceeds 89% for each list, the four lists are not equivalent.

Most of the incorrect responses were for items in List 1. Six items

in List 1 and three items in List 3 were missed by ve or more

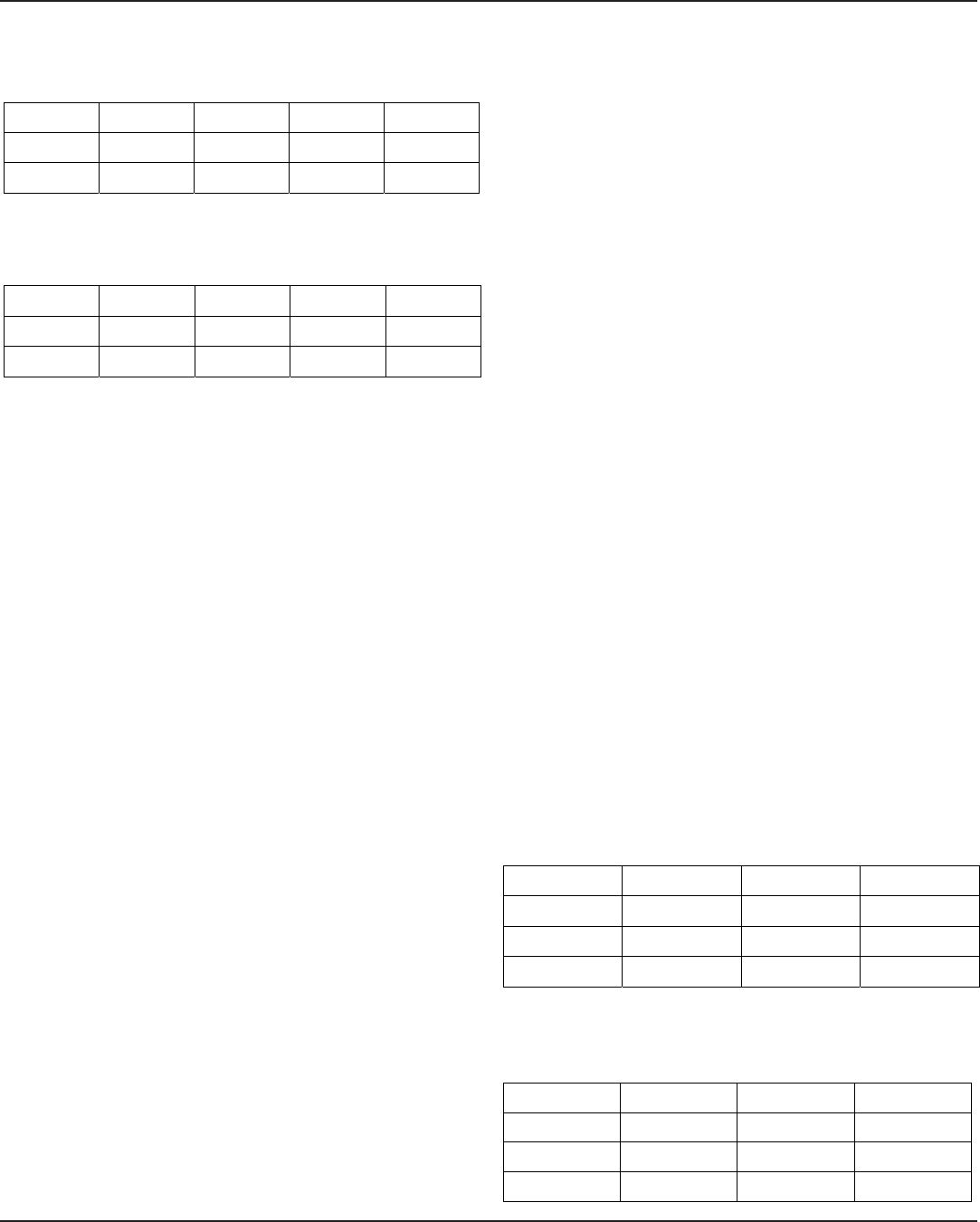

Table 1

Original WIPI Test with Items to be

Changed Bolded

List 1 List 2 List 3 List 4

school broom moon spoon

ball bowl bell bow

smoke

coat coke

goat

floor door corn

horn

fox

socks

box blocks

hat flag bag black

pan

fan can

man

bread red thread

bed

neck

desk

nest

dress

stair bear chair pear

eye pie fly tie

knee tea

key

bee

street

meat

feet teeth

wing

string spring

ring

mouse clown crown

mouth

shirt

church dirt

skirt

gun

thumb

sun

gum

bus

rug cup bug

train cake snake plane

arm

barn car star

chick stick dish fish

crib ship bib

lip

wheel

seal queen green

straw dog saw frog

pail

nail

jail

tail

41

The Word Intelligibility by Picture Identication (WIPI) Test Revisited

children. Lists 2 and 4 did not display a consistent error pattern.

Most of the errors were corrected in the naming condition. A

signicant correlation was found between age and percentage of

errors (r

2

= 0.77, p<.01) with the younger participants making

more errors than older participants. However, nine test pages had

two pictures that were consistently confused. Some of these errors

were attributed to poor pictorial representations. For example, for

the test item “shirt,” several children pointed to a picture of a girl

who is wearing a shirt. Other errors were judged to be appropriate

auditory confusions. For example, for the test item “mouse,”

several children pointed to a picture of a “mouth.” Test page 14

had two items that were particularly problematic. The test items on

this page are “ring,” “wing,” “string,” and “spring” with the foils

“king” and “swing.” “Spring” and “string” were among the items

most often incorrectly identied by the participants. It was felt

that these items were not easily recognizable by young children.

These results indicated that additional modications were needed

to construct the nal updated version of the test. Those items that

still presented pictorial confusions were redrawn (2 items) and

two foil stimuli (“king” and “swing”) replaced test items “spring”

and “string,” which were often misidentied by the children. In

addition, to create better list equivalency, three test items from List

1 were exchanged with 3 items on the same page from List 4. In the

nal evaluation these changes underwent empirical investigation.

Final Evaluation

Participants. Two groups of children who had not participated

in the preliminary investigation took part in the nal evaluation.

Group 1 consisted of fteen children (6 males and 9 females).

Group 1 ranged in age from 3.0 to 6.0 years (Mean age: 4.4;

S.D: 0.93). Group 2 consisted of nineteen children (8 males and

11 females). Group 2 ranged in age from 2.2 to 4.8 years (Mean

age: 3.6; S.D: 0.85). Results of a t-test indicated a signicant

difference of the mean age between the two groups at the .05 level.

No participants were currently receiving speech and/or language

therapy as noted by parent report. All of the children received a

hearing evaluation prior to participation. As noted previously,

hearing thresholds were measured at the octave intervals between

250 and 8000 Hz bilaterally using a portable audiometer (Beltone

Model 119) in a double walled sound-treated booth. Play

audiometry was utilized for younger participants. Hearing was

considered normal if thresholds at all test frequencies bilaterally

were better than 20 dB HL (ANSI, 1989).

Test procedures. For Group 1, the four revised test lists were

presented at average conversational level outside a soundbooth

utilizing the procedures outlined in the preliminary evaluation.

For Group 2, the revised lists were presented through a GSI-61

audiometer and TDH-39 headphones in a double walled sound-

treated booth at 40 dB SL re: the average of pure tone thresholds

at 500, 1000 and 2000 Hz. For both groups, the order of list

presentation was randomly assigned. All test items were presented

with a carrier phrase (“Show me...”). Play audiometry was utilized

with younger participants as needed. Each participant was given

verbal and/or pantomime instructions of the task by the examiner.

A practice item was presented prior to testing to insure that each

child understood the task. The examiner scored each test item at

the time of testing.

Results. Table 3 shows the nal WIPI test items. The

equivalency of the revised lists was assessed by comparing the

mean scores and standard deviations for each list. The results

are shown in Tables 4 and 5 for Groups 1 and 2, respectively.

It can be seen that the percentage of items correct exceeds 98%

for each list for those administered via live voice (Group 1) and

exceeds 88% for each list for those administered via headphones.

Performance is similar within groups across lists. An analysis of

variance (ANOVA) showed no signicant differences between

Table 2

Mean Percentage Correct (and Standard Deviation) for the Revised WIPI Lists

List 1 List 2 List 3 List 4

Mean 89.2 95.2 93.4 96.4

Std Dev 10.2 7.8 8.2 4.7

Table 3

Final WIPI Test Items

List 1 List 2 List 3 List 4

school broom moon spoon

ball bowl bell bow

smoke coat coke goat

floo

r

doo

r

corn horn

fox socks box blocks

hat flag bag black

sand fan can man

bread red thread bed

egg desk nest dress

stai

r

bea

r

chai

r

pea

r

eye pie fly tie

knee tea key bee

street meat feet teeth

wing swing king ring

mouth clown crown mouse

shirt church dirt skirt

gun thumb sun gum

bus rug cup bug

train cake snake plane

arm barn ca

r

sta

r

chick stick dish fish

crib ship bib lip

wheel seal queen green

straw dog saw frog

tail nail jail pail

42

Journal of Educational Audiology vol. 15, 2009

mean scores across lists for either group. However, signicant

between group differences were noted at the .05 level. That is,

mean percent correct identication for Group 2 was poorer than

Group 1. This difference is not unexpected and may be attributed

to the differences in presentation method (through an audiometer

versus face to face). The differences in age between groups may

have also been a contributing factor.

The Pearson product-moment correlations coefcients for

the four lists are shown in Tables 6 and 7 for Groups 1 and 2,

respectively. The correlations range from 0.60 to 0.81. All

correlations were found to be statistically signicant at the .01 level.

These correlations, along with non-signicant mean differences,

suggest that the four lists are not different.

Discussion

The assessment of speech understanding is important because

it has inherent face validity. That is, most individuals with hearing

loss report difculties understanding speech. It may be especially

crucial for the pediatric population as an integral part of any

auditory rehabilitation program for children using hearing aids or

cochlear implants. To ensure accurate assessment, the materials

should be within the receptive vocabulary of young children and the

response mode should be age appropriate. The WIPI has remained

among the most popular closed-set task for word identication in

young children since its development over 30 years ago. The test

items are within the vocabulary of most preschool children and

the picture pointing response mode is easy for even the youngest

preschool child.

The present study was designed to evaluate an updated

version of the WIPI

1

test. Pictures that were deemed outdated

or unrecognizable were modied for a contemporary audience.

Based on the results, it appears that the revised test is suitable for

preschool-aged children. As with the earlier version of this test, the

test scores are suitable for evaluating an individual’s discrimination

ability, the relative difference of performance between ears, as well

as the relative difference between aided and unaided conditions.

While the scores obtained from this test can be utilized in much

the same way as conventional speech recognition tests, the scores

cannot be considered equivalent. The present test is a closed-set task

with chance scores approximating seventeen percent. In contrast,

conventional open-set tasks have chance scores of essentially zero

percent. Thus, individual differences across test measures are to be

expected. That is, one should not expect an individual to receive

the same scores for an open- versus closed-set test.

It is acknowledged that there are limitations to this study. The

sample size is small, which may have impacted the results. Also,

data were not collected under headphones for all test conditions.

Similarly, recorded test materials were not used. Best practice for

test standardization would dictate that this should be done and

for a larger sample size (Bilger, 1984). Thus while these results

suggest the revised test is appropriate for use with preschool-aged

children, it is recommended that the ndings of this investigation

be interpreted with some caution.

It also would have been desirable to obtain data from children

with hearing loss, as well as those with normal hearing, when

developing this revised version. However, the practical difculties

with securing this subject population hindered achieving this

goal. The inclusion of items from the original WIPI was based on

empirical data from children with hearing loss demonstrating that

the stimulus items were within the receptive vocabulary of these

children. Given that only one item from the original test, the foil

“ink well,” was eliminated and replaced with a new word “sink” in

the revised test, it is reasonable to suggest that the vocabulary would

still be appropriate for use with children with hearing impairment.

Table 7

The Pearson Product-Moment Correlations between the Final WIPI Lists for Group 2

List 2 List 3 List 4

List 1 0.57* 0.74* 0.59*

List 2 0.66* 0.61*

List 3 0.67*

*Denotes significance at the .03 level or better.

Table 4

Mean Percentage Correct (and Standard Deviation) for the Final WIPI Lists for Group 1

List 1 List 2 List 3 List 4

Mean 98.5 99.7 99.1 98.8

Std Dev 2.0 1.1 1.8 1.9

Table 5

Mean Percentage Correct (and Standard Deviation) for the Final WIPI Lists for Group 2

List 1 List 2 List 3 List 4

Mean 88.2 89.6 89.4 90.1

Std Dev .09 .09 .07 .06

Table 6

The Pearson Product-Moment Correlations between the Final WIPI Lists for Group 1

List 2 List 3 List 4

List 1 0.81* 0.75* 0.60*

List 2 0.74* 0.78*

List 3 0.67*

*Denotes significance at the .01 level

1

The updated version of the WIPI is available through Auditec, St. Louis, Missouri.

43

The Word Intelligibility by Picture Identication (WIPI) Test Revisited

References

ANSI (1989) American national standard specications for

audiometers. ANSI S3.6-1989. New York: ANSI.

Bilger, R.C. (1984). Speech recognition test development. ASHA

Reports, 14, 2-7.

Dengerink, J. & Bean, R. (1988). Spontaneous labeling of

pictures on the WIPI and NU-CHIPS by 5-year-olds.

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 19(2),

144-52.

Geers, A. & Moog, J. (1990). Early speech perception test. St.

Louis: Central Institute for the Deaf.

Jerger, S. & Jerger, J. (1982). Pediatric speech intelligibility test:

Performance intensity characteristics. Ear and Hearing, 3,

325-334.

Katz, J. & Elliot, L. (1978). Development of a new children’s

speech discrimination test. Paper presented at the American

Speech and Hearing Association. San Francisco, CA.

Madell, J. (1998). Behavioral Evaluation of Hearing in Infants

and Young Children. New York, New York: Thieme.

Martin, F. & Clark, J. (1996). Behavioral hearing tests with

children. In F. Martin & J. Clark (Eds.), Hearing Care for

Children (pp. 115-134). Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon.

Martin, F. & Gravel, J. (1989). Pediatric audiological practices in

the United States. The Hearing Journal, 42, 33-48.

Northern, J. & Downs, M. (2002). Hearing in Children.

Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Ross, M. & Lerman, J. (1970). A picture identication test for

hearing impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing

Research, 13, 44-53.

Sanderson-Leepa, M. & Rintelmann, W. (1976). Articulation

functions and test-retest performance of normal-hearing

children on three speech discrimination tests: WIPI, PBK-50,

and NU Auditory Test No. 6., Journal of Speech and Hearing

Disorders, 41, 503-519.

Stewart, B. (2003). The Word Intelligibility by Picture

Identication Test: A two-part study of familiarity and use.

Journal of Educational Audiology, 11, 39-48.

Table 6

The Pearson Product-Moment Correlations between the Final WIPI Lists for Group 1

List 2 List 3 List 4

List 1 0.81* 0.75* 0.60*

List 2 0.74* 0.78*

List 3 0.67*

*Denotes significance at the .01 level