REPORT OCTOBER 2017

New Americans

and a New Direction

The Role of Immigrants in Reviving the Great Lakes Region

CONTENTS

Executive Summary 1

Background 5

Population Trends 7

Demographic Challenges 11

Manufacturing 15

— Case Study: STEM and Main Street in Akron, Ohio 16

Healthcare 23

— Case Study: Healthcare in Cleveland 27

Agriculture 30

Entrepreneurship 33

— Case Study: Entrepreneurship in Detroit 34

Spending Power, Taxes & Home Ownership 40

Conclusion 45

Data Appendix 47

Endnotes 50

New Americans

and a New Direction:

The Role of Immigrants in

Reviving the Great Lakes Region

Paid for by the Partnership for a New American Economy Research Fund

© Partnership for a New American Economy Research Fund.

Acknowledgments

New American Economy would like to thank Brandon Mendoza,

Manager of Government Affairs at the Greater Pittsburgh Chamber

of Commerce, and Steve Tobocman, Director of Global Detroit and

founder of the Welcoming Economies Global Network, for their invaluable

feedback during the drafting of this report. We are grateful for their

thoughtful comments and important local insight to ensure that this

report reflects the reality on the ground in their communities.

Executive Summary

T

he Great Lakes region, an area often referred

to as the “Rust Belt,” once represented the

pinnacle of American prosperity. Millions of

workers built the global automobile industry and poured

hot steel in a booming economy that rewarded them

with good pay and benets. While the region’s economy

still plays an important role in the nation’s economy, its

economic dominance has waned considerably. With the

rise of automation and an increasingly global economy,

industries that were once the lifeblood of this region

have faced a steady decline. Meanwhile, increased

productivity has decreased the number of workers

needed and eroded payrolls. These developments led

to decades of lackluster economic growth that was

felt most acutely by the people once employed by the

hardest-hit industries.

The fortunes of the working-class in the Great Lakes

region has become a centerpiece of the national

conversation on the state of the economy, and was

a focus of the 2016 presidential campaign. On the

campaign trail, immigration became tied to a larger

conversation on the decline of once vibrant industries

in this part of the country, making it easy for rhetoric

of zero-sum competition between U.S.-born and

foreign-born residents to take hold. Although the vast

majority of economists agree that immigration helps

expand the economy and creates more opportunities

for U.S. workers, some politicians have capitalized on

the economic angst facing the region and singled out

immigrants as the cause.

The reality, however, reects a very dierent state

of aairs. While the region indeed lost more than

one million working-class jobs and saw real wages of

workers with less than a bachelor’s degree fall by 6.4

percent between 2000 and 2015, immigrants have

actually helped to revitalize and strengthen industries

like manufacturing and healthcare, creating jobs for

Americans that once seemed lost forever. In many

vibrant Great Lakes metro regions, foreign-born

residents have also helped oset decades of population

decline, reinvigorating local economies with new

businesses, an increased tax base, and consumer

spending that has helped drive local growth. These

experiences make a strong case that there is tremendous

economic growth potential for those Great Lakes metro

areas that embrace immigrants.

Immigrants help

revitalize industries

like manufacturing

and healthcare.

In this report, we analyze the impact that immigrants

are having on the region. We nd that despite the bleak

tone used in many “Rust Belt” narratives, there are

many bright spots in the Great Lakes region’s economy

and reasons for optimism for the future. Using data

primarily from the American Community Survey for the

seven states and 98 metropolitan areas in the region,

our research shows that immigration has been and will

continue to be key to regional recovery, as immigrants

bring with them the talent, labor, entrepreneurial

spirit, and spending power needed to help x the Great

Lakes' economic engine. Far from being the cause of

the economic struggles that have set in over the past

decades, immigration may in fact provide one of the

most promising solutions to them.

New Americans and a New Direction | Executive Summary

1

Immigration fuels population growth in the Great Lakes region.

Immigrants accounted for half of regional population growth between 2000 and 2015 and oset population

decline in nine out of the top 25 metro areas in the region. The Detroit and Pittsburgh metro areas, for instance,

would have shrunk by more than 200,000 and 100,000 people, respectively, if not for the arrival of immigrants.

Immigrants are keeping the region’s workforce viable.

While only 51.1 percent of U.S.-born residents in the Great Lakes region were working-age in 2015, more than

70 percent of the area’s immigrants fell into that age band. That allowed immigrants to drive almost two-thirds

of regional growth in the size of the working-age population between 2000 and 2015. This was vital for an area

facing a rapidly aging population. The number of U.S.-born elderly increased from nine million to 11 million

during the same time period.

Immigrants are bringing much needed talent to the region.

In the Great Lakes region, where only 29.2 percent of the U.S.-born population ages 25 and above have at

least a bachelor’s degree, 35.3 percent of immigrants have that level of education. Moreover, the foreign-born

population has become even more educated in recent years. Between 2010 and 2015, more than half of the net

growth in the working-age immigrant population came from those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Immigrants have helped revive the manufacturing industry.

Despite popular perception, manufacturing has begun a robust rebound in the Great Lakes region, adding

more than 250,000 working-class jobs between 2010 and 2015, the majority of which were lled by U.S.-born

workers. This is possible, in part, because immigrants ll the higher-skilled jobs that allow companies to stay

local, as opposed to moving oshore. Foreign-born workers made up one out of every seven manufacturing

engineers in 2015.

Immigrants have played a critical role powering the region’s booming

healthcare sector.

Between 2000 and 2015, more than four out of every ve new jobs created in the Great Lakes region—or 80.3

percent—were healthcare positions. This was good news for the U.S.-born working-class, which gained more

than 570,000 new healthcare jobs. By lling the high-skilled jobs that allow doctors’ oces and hospitals to

thrive and expand, immigrants helped make such supersized growth possible. Despite representing 7.3 percent

of the region’s population, immigrants made up 27 percent of the region’s physicians and surgeons in 2015.

KEY FINDINGS

New Americans and a New Direction | Executive Summary

2

KEY FINDINGS

Immigrants are helping the Great Lakes region meet its rising labor demand

in agriculture.

Agriculture is a promising source of employment for the region’s working-class. The average wages of working-

class agricultural workers grew by 17.1 percent between 2000 and 2015, and the number of jobs at that skill level

held by U.S.-born workers grew by 9.2 percent. By taking on some of the labor-intensive farm jobs that are less

attractive to U.S.-born workers, immigrants help the sector thrive. Immigrants made up one out of every four

miscellaneous farmworkers in the region in 2015—including those who harvest crops by hand.

Immigrants play a particularly large role as entrepreneurs.

The number of immigrant entrepreneurs grew by more than 120,000 between 2000 and 2015, while fewer

U.S.-born residents took the risk of starting their own businesses. By 2015, more than one out of every 10

entrepreneurs in the region was foreign-born. Immigrants also made up more than one out of every ve of the

region’s Main Street business owners, operations that created close to 239,000 working-class jobs for U.S.-born

workers between 2000 and 2015 alone.

Immigrants’ spending power has helped revitalize local businesses.

Immigrants punch above their weight when it comes to their economic power as consumers. In 2015, they held

close to $130 billion in spending power, or 8.2 percent of the region’s total, although they represented just 7.3

percent of the area’s overall population. Robust consumer spending by immigrants supports local business

owners and keeps local economic corridors vibrant.

New Americans and a New Direction | Executive Summary

3

Without a doubt, the 27 million U.S.-born working-class

residents of the Great Lakes region face signicant

challenges. This report shows that although immigrants

alone will not be able to solve the region’s economic

problems, they do have an important role to play as

the region—and the country as a whole—shifts from

traditional manufacturing to more innovation-driven

industries, including advanced manufacturing. Without

enough high-skilled talent to sustain our changing

economy, working-class families will suer.

While this report demonstrates some promising trends,

the area’s future will depend on community leaders

embracing the 21st-century innovation economy—and

also, immigration. Some leaders in local government,

chambers of commerce, and non-prot organizations at

city, county, and state levels understand this, and have

launched economic development programs in places

like Cleveland, Detroit, and Pittsburgh that involve

attracting more immigrants and the prosperity they

can bring. But the federal government’s next steps on

immigration reform might weigh heavily on the region’s

future. To inform the immigration debate, this report

makes a strong case for federal, state, and local policies

that welcome immigrants. By tapping into immigrants’

economic contributions, the Great Lakes region will be

on track to shake o the remaining “rust” and reclaim

its glory as an economic powerhouse, brightening the

future of many working-class Americans in a rapidly

changing global economy.

By tapping

into immigrant

contributions, the

Great Lakes region

will be on track to

reclaim its glory

as an economic

powerhouse.

New Americans and a New Direction | Executive Summary

4

F

ew parts of the country are as closely associated

with the working-class as the region sometimes

referred to as the Rust Belt. In 2015, one out of

every four working-class people in the United States

lived in the area, which we refer to as the Great Lakes

region throughout this report. The 2016 election threw a

spotlight on the economic challenges that have plagued

the region for years: Following the rise of technology and

automation, the American working-class has struggled,

unable to nd the ladder to prosperity that was so easily

accessible to their parents. Between 2000 and 2015, the

number of working-class jobs in the region fell by 1.1

million. On top of that, real wages for that group fell by

6.4 percent.

Following the rise

of technology and

automation, the

American working-

class has struggled.

In this report, we explore how immigrants—despite

political rhetoric to the contrary—may be helping

improve working-class Americans’ economic prospects.

To do this, we start with a simple, widely held premise:

That the industries that will power the region in the

coming decades will look far dierent from the ones

that dominated the past.

1

From 2000 to 2015, only

four industries—healthcare, agriculture, professional

services, and the combined oil, gas, and mining

sector—both added jobs for the U.S.-born working-

class and increased their wages. The rapid growth in

oil, gas, and mining appears largely driven by a boom

in shale gas extraction, a source of employment that

has shrunk considerably since 2015.

2

To understand the

future of the region, then, we explore how foreign-born

Americans contributed to the other three sectors that

are increasingly oering promising opportunities for the

working-class.

3

We also discuss the way immigrants are

helping to strengthen the manufacturing industry—a

sector that has begun to rebound in the years since

2010, largely reinventing itself through high-tech and

advanced manufacturing work.

It is important to note that immigrants are still a

relatively small portion of the Great Lakes region’s

population. In 2015, the region was home to 5.6 million

immigrants, a group that made up 7.3 percent of the

overall population. The thousands of new immigrants

arriving in the region each year, however, play an outsize

role in reversing population decline, a factor we discuss

in detail in this report. They also start new businesses

and create opportunities for American workers in

startling numbers. The almost $130 billion foreign-born

households have in spending power—or income after

taxes—allows their pocketbooks to strengthen both the

housing market and the many businesses dependent

upon paying customers to survive.

Before getting into our results, however, it is necessary

to rst establish some denitions and terms. Following

much of the academic literature, we dene working-

class as anyone with less than a bachelor’s degree.

4

Immigrants are individuals who were born abroad to

non-U.S.-citizen parents. The Great Lakes region, as we

dene it, encompasses the historically manufacturing-

heavy area largely in the Midwest and Upper Midwest,

Background

New Americans and a New Direction | Background

5

WI

IL

IN

OH

PA

NY

MI

FIGURE 1: THE GREAT LAKES REGION

Wisconsin

Illinois

Indiana

Michigan

Ohio

Pennsylvania

New York

Excludes

New York City

metro area

Note: Metropolitan areas may extend beyond borders of

these states. For full list of metro areas included in this

report, see Data Appendix.

including seven states: Illinois, Indiana, Michigan,

upstate New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

5

For metropolitan areas that extend beyond the borders

of these states, such as Minneapolis, Minnesota, which

includes parts of Wisconsin, and Louisville, Kentucky,

which includes parts of Indiana, our analysis looks at the

entire metro area so we can fully capture the economic

picture of these communities as a whole. Figure 1 shows

the boundaries of the area that is the focus of this report.

In recent years, a variety of cities in the Great Lakes

region—from Cleveland to Detroit to Pittsburgh—have

embraced policies that welcome, rather than push away,

new Americans and refugees. While political rhetoric

might lead one to believe this runs counter to their

interests, policymakers in this region frequently argue

that immigrants are one of their best hopes to stem

population decline, reinvigorate entrepreneurship, and

attract the next generation of promising employers.

This report provides evidence that such civic leaders

are not only right—but steering the region in a

promising direction.

New Americans and a New Direction | Background

6

Population Trends

PART I

A

s factories closed amid the economic downturn

in the Great Lakes region, people started

to leave for job opportunities elsewhere,

such as the rapidly growing Sun Belt. This caused

neighborhoods in many cities to fall into decline,

adding to the cycle of foreclosures, rising crime, and

underfunded and struggling schools and public services.

In the past few decades, these scenes have taken place in

many Great Lakes cities hit hard by deindustrialization.

Although the situation is improving in many

communities like Columbus, Ohio; Milwaukee; and

Minneapolis, our research shows that some areas of

the region have continued to lose population in more

recent years. Eight out of the region’s top 25 metro areas

suered population declines between 2000 and 2015.

Detroit, for instance, lost more than 141,000 residents.

In Cleveland, the equivalent gure was more than

91,000 people. Outside the cities, the non-metro areas

in the region also experienced population decline, with

the number of residents there falling by 1.2 percent.

Due to such trends, the overall population growth in the

Great Lakes region in recent years has lagged behind the

national average. The region’s total population increased

by 4.3 percent between 2000 and 2015—a number

dwarfed by the overall U.S. population growth rate of

14.2 percent over the same period of time. (See Figure 2.)

This is important because a shrinking population hurts

local growth prospects: Having fewer residents lowers

tax revenues that support municipal services and school

systems, dampens consumer spending, reduces job

opportunities, and stalls business creation. In the long

term, population decline also undermines cities’ political

clout and ability to attract government funding and jobs

at the state and federal levels.

To break this vicious cycle of depopulation and to

spur economic growth, political leaders in the region

are looking for ways to boost their populations. Many

chambers of commerce in the region, in fact, cite

population decline as their biggest challenge. Without

workers and talent, it can be hard to convince companies

to set up shop—and stay—in the region.

Population growth

in the Great Lakes

region has lagged

behind the national

trend in recent years.

FIGURE 2: POPULATION GROWTH IN THE GREAT LAKES

REGION LAGS BEHIND THE NATIONAL TREND, 2000-2015

0

2000 2015

50M

100M

150M

200M

250M

300M

Total U.S. Population

14.2%

Growth

Great Lakes Region

4.3%

Growth

New Americans and a New Direction | Population Trends

7

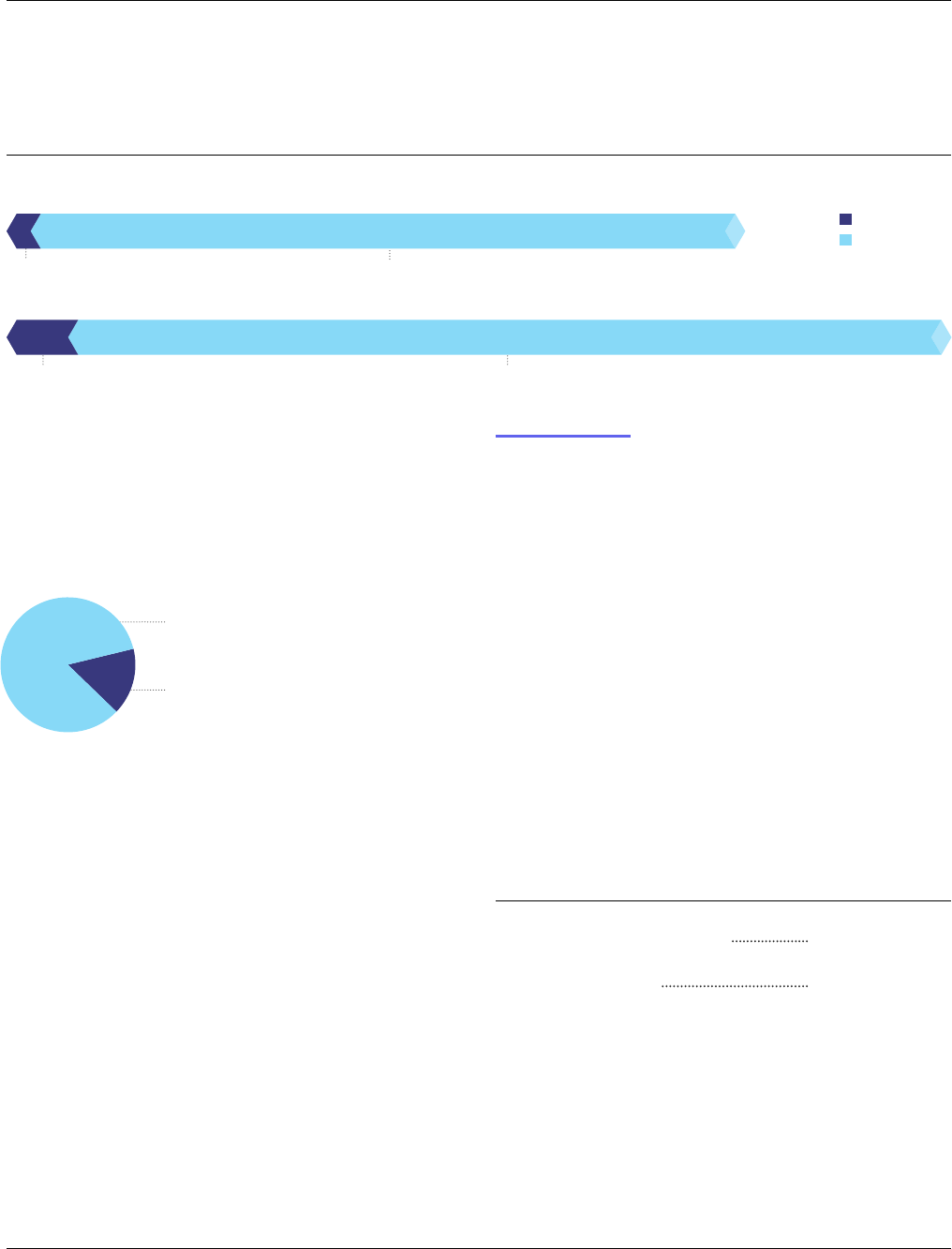

FIGURE 3: IMMIGRANTS DROVE POPULATION GROWTH IN

THE GREAT LAKES REGION BETWEEN 2000 AND 2015

1,543,264

1,559,872

+

Foreign-born

49.7%

U.S.-born

50.3%

New Residents

2000-2015

“In most Great Lakes metros, is steadily advancing,

as well as job growth,” explains Brandon Mendoza,

government aairs manager for the Greater Pittsburgh

Chamber of Commerce. “The problem is that large gaps

in our high-skilled labor pools are holding back growth

rates in places like Pittsburgh, Detroit, and Cleveland.

Add to that the general population stagnation in most

of the Great Lakes states and metros, and it’s clear our

region is missing the natural economic growth that can

result from simply adding new people. Realizing this,

we have partnered with our Mayor’s oce and with the

All For All project to make our city welcoming

to immigrants.”

Given these concerns, our nding that immigrants have

played a key role driving the population growth that

has occurred in the region in recent years is particularly

meaningful. Between 2000 and 2015, the foreign-born

population grew by 1.5 million people, accounting

for half of the overall increase in residents in the

region during the period. (See Figure 3.) The arrival of

immigrants also softened the blow of population decline

in several cities.

In Figure 4 on the following page, we show the

population trends—and how they are impacted by

immigrants—in greater detail. Among the top 25

Great Lakes metros, Akron and Syracuse would have

seen their populations decline, instead of increase, if

not for immigrants. Seven other metropolitan areas,

meanwhile, would have experienced more dramatic

population losses than actually occurred. Chief among

them is Detroit, a city that would have shrunk by more

than 220,000 people without the arrival of immigrants.

Scranton, Pennsylvania, a city that lost roughly 2,400

people between 2000 and 2015, would have seen a

population decline of more than 18,000. Dayton, Ohio,

would have seen a decline of more than 17,000.

The foreign-born

population grew

by 1.5M people,

accounting for half of

the overall increase

during this period.

Even in cities with growing populations, it is clear that

immigrants helped drive this success. In all of the

top metros where population increased, immigrants

contributed to more than 20 percent of their overall

population growth. For instance, in Philadelphia, the

foreign-born population rose by almost 250,000

people. That meant that 62.2 percent of the metro

area’s population growth can be explained directly by

the arrival of immigrants. A similar pattern holds for

Rochester, New York, where 71.2 percent of the metro’s

population growth can be attributed to the arrival of

more foreign-born residents.

New Americans and a New Direction | Population Trends

8

FIGURE 4: POPULATION CHANGE IN TOP 25 GREAT LAKES METROS, 2000-2015

Grand Rapids, MI

Madison, WI

Allentown, PA-NJ

Milwaukee, WI

Harrisburg, PA

Albany, NY

Rochester, NY

Akron, OH

Syracuse, NY

Scranton, PA

Dayton, OH

Toledo, OH

Buffalo, NY

Youngstown, OH-PA

Pittsburgh, PA

Cleveland, OH

Detroit, MI

Foreign-born

Total

U.S.-born

Minneapolis, MN-WI

Chicago, IL-IN-WI

Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD

Columbus, OH

Indianapolis, IN

Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN

Louisville, KY-IN

St. Louis, MO-IL

Detroit would

have shrunk

by more than

220,000

people without

the arrival of

immigrants.

Note: For full population figures, see Data Appendix.

504,025

461,113

399,839

351,411

333,853

166,742

155,894

134,740

106,260

102,847

89,963

76,914

57,032

54,718

22,012

11,737

9,957

2,407

4,533

12,312

39,674

50,298

88,372

91,153

141,363

New Americans and a New Direction | Population Trends

9

Our analysis also found that immigrant residents have

helped to oset decline in more rural communities. The

rural portion of the Great Lakes region, or the area not

included in any metro area, experienced a 1.2 percent

decline in overall population from 2000 to 2015. Without

the arrival of immigrants, the number of residents there

would have fallen by 1.5 percent, or at least 34,000 more

people. (See Figure 5.)

Without immigrants,

the number of

residents in the rural

areas of the Great

Lakes region would

have fallen by at least

34,000 more people.

Although the Great Lakes region still struggles with

population decline, it is worth noting that the arrival of

immigrants in recent years also likely played some role

attracting or at least retaining U.S.-born residents. A

2013 report from New American Economy found that the

arrival of immigrants in a community leads to greater

demand for goods and services, helping to sustain local

businesses, particularly service-oriented businesses like

restaurants, hair salons, and grocery stores dependent

upon customers. More residents can also give employers

ready access to specialized workers and bolster sagging

housing values. As a result, our previous study has found

that for every 1,000 immigrants moving to a county, 270

U.S.-born people are drawn there in the two decades

that follow.

6

Based on that multiplier, we estimate that

the growth in the immigrant population in the Great

Lakes region between 2000 and 2015 attracted almost

417,000 U.S.-born residents to the region as well.

Rural Population Change

2000-2015

FIGURE 5: HOW IMMIGRANTS LESSENED THE BLOW OF

POPULATION DECLINE IN MORE RURAL COMMUNITIES IN

THE GREAT LAKES REGION, 2000-2015

-137,319

-171,974

34,655

FOREIGN

BORN

TOTAL

U.S.BORN

New Americans and a New Direction | Population Trends

10

Demographic

Challenges

PART II

T

he declining population in the Great Lakes

region represents a major challenge to the area’s

economic growth. But examining the sheer

number of residents in individual cities only tells part

of the story. To truly understand why immigrants are

so important to the region, it is also useful to look at the

demographic prole of the immigrants who have come

to call the Great Lakes region home.

In recent years, the country as a whole has faced a host

of demographic challenges due to the rapid aging of the

baby boomer population. Nationwide, baby boomers are

retiring and leaving the workforce at the rate of 10,000

people per day.

7

While the United States was home to

43.7 million adults ages 65 and above in 2012, that gure

is projected to almost double by 2050, reaching

83.7 million.

8

In the Great Lakes region, however, these aging

challenges are particularly pronounced. The U.S.-

born elderly population, or those ages 65 and above,

increased by 21.2 percent from 2000 to 2015, going from

9 million to 11 million. More troubling, the number of

U.S.-born working-age adults in the region experienced

tepid growth, with the size of that population rising

by just 1.9 percent during the same period. In some

areas, the problem is even more acute. Among the top

25 metros in the region, nine experienced a decrease in

their U.S.-born working-class population between 2000

and 2015. (See Figure 6.)

In this environment, the foreign-born population is

uniquely positioned to help. Immigrants in the region

are far more likely to be of prime working age than the

U.S.-born: In 2015, 70.2 percent of immigrants were

Youngstown, OH-PA

Detroit, MI

Cleveland, OH

Dayton, OH

Scranton, PA

Buffalo, NY

Pittsburgh, PA

Rochester, NY

Toledo, OH

FIGURE 6: METROPOLITAN AREAS IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION THAT EXPERIENCED A DECLINE IN THE NUMBER OF

U.S.-BORN WORKING-AGE RESIDENTS, 2000 TO 2015

-3.9%

-0.4%

-0.2%

-7.0%

-3.0%

-8.0%

-3.4%

-4.5%

-2.0%

New Americans and a New Direction | Demographic Challenges

11

in that age group, compared with 51.1 percent of the

U.S.-born population. Despite their small share of the

overall population, immigrants drove two-thirds of the

growth in the region’s working-age population between

2000 and 2015. By participating in the labor force,

immigrants generate tax revenues that are valuable to

states struggling with rising government spending on

healthcare and other social assistance for seniors. An

inux of working-age immigrants also helps the region

ll in workforce gaps that develop as the baby boomers

retire.

FIGURE 8: IMMIGRANTS MADE UP TWO-THIRDS OF THE

GROWTH IN PRIME-AGED POPULATION IN THE GREAT

LAKES REGION, 2000-2015

Prime-Aged

Population Growth

2000-2015

FIGURE 7: AGE BREAKDOWN OF THE GREAT LAKES REGION

POPULATION, 2015

0-24 25-64 65+

FOREIGNBORN

15.4% 70.2% 14.4%

WORKING AGE

U.S.BORN

33.3% 51.1% 15.6%

WORKING AGE

Foreign-born:

1.3M

U.S.-born:

0.7M

2.0M

Total

Immigrants are also useful to the Great Lakes region—

and its employers—because of their educational levels.

In 2015, 29.2 percent of the region’s U.S.-born residents

ages 25 and older held at least a bachelor’s degree.

What’s more, just 10.8 percent had a graduate degree.

This was in sharp contrast with foreign-born residents.

In 2015, 35.3 percent of all immigrants ages 25 and older

in the region had at least a bachelor’s degree. A full 17

percent had completed a master’s or PhD program.

In recent years, the foreign-born population in the region

has become considerably more educated. Between

2010 and 2015, more than half of the net growth in the

working-age immigrant population came from those

with a bachelor’s degree or higher. In some metro areas,

this phenomenon was particularly pronounced. Take

Dayton, Ohio, a community that has made attracting

skilled immigrants a key part of its public policy in the

years since it launched its Welcome Dayton initiative in

2011. In the Dayton metro area, almost 85 percent of the

growth in the immigrant population, ages 25 and above,

that occurred between 2010 and 2015 was attributed to

high-skilled immigrants. In three other metro areas—

including Cincinnati as well as Rochester and Bualo

in upstate New York—97 percent or more of the net

increase in working-age adult immigration can be

explained by the arrival of the highly skilled.

On their own, these trends are impressive, but they gain

even more resonance when we consider how they t

into another major problem facing the area: The loss of

college-educated residents, a phenomenon known as

brain drain. As young people move out, they often take

with them the talent that is desperately needed to revive

the regional economy. Between 2014 and 2015 alone,

the Great Lakes region experienced a net loss of almost

113,000 U.S.-born residents with a bachelor’s degree or

above. Immigration helped mitigate this brain drain, as

more than 177,000 foreign-born college degree holders

moved to the region, outnumbering the ones moving out

and leading to a net gain of close to 5,000 high-skilled

residents for the region overall. (See Figure 9.)

New Americans and a New Direction | Demographic Challenges

12

FIGURE 9: MIGRATION OF HIGH-SKILLED RESIDENTS, 2014-2015

Between 2014-2015, 642,439

high-skilled workers moved in.

During the same period,

750,124 moved out.

U.S.-born:

465,380

U.S.-born:

577,993

Foreign-born:

177,059

Foreign-born:

172,131

Between 2014 and

2015, the region

lost almost 74,000

U.S.-born college-

educated millennials

but gained more than

18,000 foreign-born.

A similar pattern of brain drain occurred among

highly educated millennials, those ages 22 to 34, a

group particularly important to the area’s long term

competitiveness and growth. Between 2014 and 2015,

the region lost close to 74,000 U.S.-born college-

educated millennials. At the same time, however, it also

gained more than 18,000 foreign-born millennials with

college degrees. Among the more than 100,000 college-

educated immigrant millennials who moved into the

region, 29.1 percent were graduate students pursuing

advanced degrees and close to one out of every four

were Science, Technology, Engineering, or Math-related

() workers replenishing the high-skilled labor force.

Given that immigrants have been found to earn more

patents than the U.S.-born, these skilled individuals help

increase the level of innovation in the region. One past

study found that 74 percent of patents awarded to

the University of Michigan and 71 percent of patents

awarded to the University of Wisconsin System in 2011

had at least one foreign-born inventor.

9

While high-skilled foreign-born individuals have

helped stem brain drain in the region, many local

policymakers have realized they could see even more

economic benets if a larger share of the region’s many

international students remained in the country after

graduation. The Global Talent Retention Initiative of

Michigan, a program of Global Detroit, for instance,

has created a registry of employers willing to hire

immigrants and international graduates. It also

hosts semi-annual job fairs attracting more than 300

graduate students and conducts other on-campus

networking opportunities connecting international

students directly to relevant employers with unmet

talent needs.

10

In St. Louis, a city that has struggled

New Americans and a New Direction | Demographic Challenges

13

In 2015, immigrants

made up roughly

one out of every six

STEM workers in

the region.

to ll some high-skilled jobs in recent years, a similar

program was created to educate international students

in interviewing techniques and aide employers trying to

navigate the country’s byzantine immigration system on

behalf of new hires.

11

The foreign-born population has helped the region

develop a workforce with much-needed skills in .

As our economy evolves to be more technology driven,

such skills are incredibly important to employers. In the

Great Lakes region, however, they are in particularly

short supply. Past research has found that in 2015,

21 jobs were advertised online in Indiana for every one

unemployed worker in the state.

12

In Michigan,

19.1 jobs were advertised for each unemployed

worker. In no state in the region was the ratio of

jobs to unemployed workers less than 11:1.

In this environment, immigrants have emerged as

a crucial source of talent. In 2015, they made

up roughly one out of every six workers in the

region, despite making up 7.3 percent of the population

overall. In the region’s colleges and universities, they

also made up a large share of students graduating with

advanced degrees. In the 2015-2016 school year,

international students earned 41.2 percent of graduate-

level degrees at the region’s most research-

intensive universities.

FIGURE 10: THE OUTSIZE ROLE IMMIGRANTS PLAY AS

STEM WORKERS IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION, 2015

Foreign-Born

in the Great Lakes

Region

Share of STEM workers

16.1%

Share of the population

7.3%

New Americans and a New Direction | Demographic Challenges

14

Working-class

Jobs

3.9%

All

Manufacturing

8.5%

All Jobs

6.0%

T

he rise and the fall of manufacturing has greatly

shaped the Great Lakes economy as it is today.

As mentioned previously, manufacturing

employment began declining in the Great Lakes region

in the 1970s, driven largely by increasing automation

and rising competition from other regions—both

domestic and overseas—with cheaper labor costs. The

hemorrhaging of jobs continued into the 2000s.

13

Between 2000 and 2010, the Great Lakes region lost

almost 1.6 million manufacturing jobs. The bulk of

that economic blow fell on workers without bachelor’s

degrees: All but 18,000 of the jobs lost during that

period were positions that were once lled by working-

class individuals.

In more recent years, however, the manufacturing

industry has shown signs of a strong comeback. After

bottoming out in the Great Recession, the number of

people employed in the region’s manufacturing industry

actually increased between 2010 and 2015, rising by

more than 403,000 workers. This outpaced the region’s

broader economic growth. While the number of jobs

in the region overall increased by 6.6 percent, jobs in

manufacturing grew by 8.5 percent. (See Figure 11.)

Employed manu-

facturing workers

rose by more than

403,000 between

2010 and 2015.

The recent trend has brought at least some measure of

relief to the large population of displaced former factory

workers. Between 2010 and 2015, the unemployment

rate among working-class individuals whose last job was

in manufacturing fell from 12.9 to 4.8 percent. This was

during a period when more than 250,000 working-class

manufacturing jobs were created in the region, the vast

majority of which, or 92.9 percent, went to workers who

were U.S.-born.

Manufacturing

PART III

All Industries Manufacturing Only

FIGURE 11: MANUFACTURING AS A JOB GENERATOR IN THE

GREAT LAKES REGION, 2010-2015

Jobs Growth

2010-2015

Working-class

Manufacturing

7.3%

New Americans and a New Direction | Manufacturing

15

New Americans and a New Direction | Case Study: STEM and Main Street in Akron, Ohio

16

STEM and Main Street

in Akron, Ohio

L

ike many cities in the Great Lakes region, the

economy of Akron, Ohio, rose and fell with the

U.S. auto industry. In the 1950s, the city was

known as “The Rubber Capital of the World,” due to its

role providing tires to U.S. and foreign automakers. Four

of the country’s ve largest tire suppliers—B.F. Goodrich,

Firestone, General Tire, and Goodyear—all were based

in the northeastern Ohio city. At its height, the rubber

industry supplied jobs to almost 60,000 local workers.

14

But the tide began to change in the 1980s. Goodrich,

Firestone, and General Tire all closed their factories in

Akron, leaving behind thousands of acres of abandoned

industrial space. Between 1980 and 1990, the metro area’s

economic output fell by 38 percent.

15

Just 16,000 people

were still employed in the rubber industry by 1990.

16

As the city searched for new ways to reinvigorate and

modernize its economy, one transformative gure

emerged: Luis Proenza. A Mexican immigrant, Proenza

served as president of the University of Akron from

1999 to 2014.

Like many university presidents, Proenza aimed to

draw talent and funding to campus. But he also strongly

believed that a university should capitalize on its

expertise to drive economic growth for the region it

serves—something he came to call the Akron Model.

17

He expanded campus buildings into town, created

institutions tasked with linking university research with

the needs of industry, and recruited business executives

to help.

18

Proenza is now credited with helping to

cement Akron’s standing as a world leader in polymer

research, a move that created thousands of local jobs.

19

Polymers are long-chained molecules that, as Proenza

explains, “make up virtually everything we know and

value, including plastics, rubber, elastomers, coatings,

and most of ourselves.”

20

Today, he says, more than

1,800 polymer companies operate in northeast Ohio.

“There’s been a huge proliferation of small, medium, and

large polymer companies in our area,” he says, “making

Ohio the largest employer of polymer-related products

in the country, and maybe the world.”

CASE STUDY

An Economy Transforming:

New Americans and a New Direction | Case Study: STEM and Main Street in Akron, Ohio

17

The success of Akron’s polymers industry has not only

benetted high-skilled workers, but the U.S.-born

working-class population in the metro area as well.

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of working-class

jobs in Akron’s advanced manufacturing industry—the

sector that includes most polymer rms—swelled by

17.3 percent. This was more than three times faster than

the growth in overall working-class employment in the

area during that period. Almost two out of every three of

the new working-class jobs in advanced manufacturing

were lled by U.S.-born workers.

Advanced manufacturing also proved to be a promising

source of wage generation for Akron’s working-class.

The real wages of U.S.-born workers in the sector

with less than a bachelor’s degree grew by 6.3 percent

between 2010 and 2015 alone.

While Proenza obviously did not build the polymers

industry, many Akron business leaders credit the

broader foreign-born population with helping to sustain

it. The modern polymers industry is driven largely by

high-tech innovations, making it dependent on the

existence of researchers skilled in science, technology,

engineering, and math, or elds. Here foreign-

born experts play an outsize role. In the Akron metro

area, immigrants made up just 5.4 percent of the

population in 2015, but 10.9 percent of the area’s

workers that year. And at the University of Akron, 56

percent of all students earning Master’s or PhD degrees

in elds in 2016 were international students in

the country on temporary visas. Given this, it is little

surprise that numerous local startups created to test and

market medical interventions using polymers derive

from the innovations of immigrants. The innovations

include a coating that prevents scar tissue from forming

over arterial stents (already placed in more than six

million patients);

a skin-like glue to suture wounds; a

exible screw for use in spinal surgery; and a cancer-

ghting drug that can be delivered directly from a

prosthetic breast for targeted therapy.

21

Foreign-born entrepreneurs have also been behind

several promising local polymer rms. Akron Polymer

Systems, a company that makes distortion-free coatings

for high-denition televisions and instrument panels,

was co-founded by an immigrant, as was Akron Ascent

Technologies, a rm that has developed an aordable,

gecko-like dry adhesive. Adhesive behemoth Velcro

has invested in the latter rm, which plans to bring its

product to market later this year.

22

Beyond polymers, immigrant entrepreneurs have also

played a role helping Akron with another one of its

enduring problems: widespread vacancies downtown.

Large numbers of Bhutanese refugees began arriving

in the city in 2007. In North Hill, an old neighborhood

on the city’s northeast side, these refugees have opened

more than two dozen groceries, shops, and restaurants,

says Jason Segedy, Akron’s director of planning and

urban development.

The immigrant-fueled revitalization continues a

pattern that began during World War I, when new

Americans from Italy and, later, Poland moved into the

neighborhood. But as immigration rates dropped and

people moved to the suburbs, the neighborhood fell

into decline. By the turn of the century, housing vacancy

rates had climbed to as high as 15 percent, says Segedy.

“The neighborhood was looking fairly tired and suering

some blight,” he says. Now, thanks to a new wave of

foreigners vacancy rates have dropped to two percent

and the neighborhood exudes energy. “The perception

of North Hill has really picked up,” Segedy says. “It’s

viewed now as an up-and-coming, more vibrant,

welcoming place.”

One new North Hill business owner is Naresh Subba,

a Bhutanese refugee who opened a grocery store

with his brothers in 2011. He employs seven people,

and added three U.S.-born high school students this

summer as part of a county jobs-skills program for low-

income teenagers. He shares the neighborhood with a

Bhutanese jewelry store, a Nepalese mini bazaar, a Thai

market, and many more.

They do far more than merely make the neighborhood

more livable, Subba says. Main Street businesses create

local jobs, boost city tax revenues, and prop up housing

prices. Indeed, the North Hill neighborhood now has

one of the fastest-growing housing markets in the city.

23

FIGURE 12: CHANGE IN EMPLOYMENT AND AVERAGE WAGE FOR U.S.-BORN WORKING-CLASS, 2010-2015

Workers in the manufacturing industry also saw

meaningful wage gains. The average wage of U.S.-born

working-class manufacturing workers rose by 2.3 percent

between 2010 and 2015. Although that sounds relatively

small, it is almost ve times faster than the wage

increase experienced by the U.S.-born working-class

population in the region overall during that same period.

These promising trends were repeated in many

metropolitan areas. Seventeen of the top 25 metros

in the region saw growth in the number of U.S.-born

working-class individuals working in manufacturing

between 2010 and 2015. Albany, New York, took the

lead, with a 31.3 percent increase in U.S.-born working-

class employment in manufacturing, while Louisville,

Kentucky, experienced a 27.5 percent jump in the

number of positions. Long known as a national leader

in furniture design and manufacturing, as well as the

assembly of automotive parts, employers in Grand

Rapids, Michigan, have expanded into a variety of

other manufacturing subsectors in recent years, such

as aerospace.

24

This diversied growth resulted in the

number of jobs in manufacturing held by the U.S.-born

working-class rising by 29.1 percent in Grand Rapids

between 2010 and 2015 alone.

Average wage of

U.S.-born working-

class employees

rose almost five

times faster in

manufacturing

than overall.

20M

0

$20k

2010 20102015 2015

5M

$30k

10M

$40k

15M

All working-class

All working-class

Manufacturing working-class

Manufacturing working-class

Jobs Growth Average Wage Growth

Industry 2010 2015 Growth

All working-class 20,009,181 20,694,245

3.4%

Manufacturing

working-class

3,141,692 3,378,800

7.5%

Industry 2010 2015 Growth

All working-class $33,677 $33,854

0.5%

Manufacturing

working-class

$43,302 $44,287

2.3%

$50k

Manufacturing

New Americans and a New Direction | Manufacturing

18

FIGURE 13: TOP TEN GREAT LAKES METROS WITH FASTEST GROWTH IN U.S.-BORN WORKING-CLASS EMPLOYMENT IN

MANUFACTURING, 2010-2015

31.3% — ALBANY, NY

19.0% — DAYTON, OH

27.5% — LOUISVILLE, KYIN

16.6% — DETROIT, MI

11.6% — MILWAUKEE, WI

29.1% — GRAND RAPIDS, MI

16.7% — AKRON, OH

26.4% — TOLEDO, OH

12.7% — COLUMBUS, OH

11.4% — PITTSBURGH, PA

7.5% — THE GREAT LAKES REGION

Average Regional Growth

U.S.-Born Working-Class Employment in Manufacturing

Fastest Growing Metros

Seventeen

of the top 25

metros in the

region saw

growth in the

number of U.S.-

born working-

class individuals

working in

manufacturing

between 2010

and 2015.

1

3

7

9

4

8

10

2

6

5

New Americans and a New Direction | Manufacturing

19

But how do immigrants play into this narrative? The

resurgence of the region’s manufacturing sector is

possible, in part, because immigrants often ll the

jobs that allow companies in the region to remain

competitive in a global economy. In an environment

where many highly educated Americans leave the

region, immigrants frequently step up to ll high-skilled

manufacturing positions and provide companies with

the talent they need to keep operations local. One out of

every seven manufacturing engineers in the Great Lakes

region was foreign-born in 2015—a share much larger

than the percent of immigrants in the overall population.

(See Figure 14.)

One out of every

seven manufacturing

engineers in the Great

Lakes region was

foreign-born in 2015.

+P

7+M

FIGURE 14: THE OUTSIZE ROLE IMMIGRANTS PLAY AS

MANUFACTURING ENGINEERS IN THE GREAT LAKES

REGION, 2015

Foreign-Born

in the Great Lakes

Region

Share of manufacturing engineers

13.5%

Share of the population

7.3%

Moreover, roughly one out of every three immigrants

in the manufacturing sector had at least a bachelor’s

degree in 2015. The equivalent gure for the U.S.-born

population in the region was just 25.8 percent.

The unique role played by immigrants in the

manufacturing sector is particularly important because

of the type of manufacturing rms that are taking root

and expanding in the region now. Between 2010 and

2015, two-thirds of the regional growth in manufacturing

employment came from the advanced manufacturing

industry, or companies that invest a substantial portion

of their budgets on research and development. Such

rms, which are far dierent from more traditional

manufacturers, typically require a pool of highly

skilled workers to thrive.

25

Indeed, between 2000 and

2015, almost 150,000 of the new manufacturing jobs

created in the region required workers to have at least

a bachelor’s degree. If advanced manufacturing rms

making products like medical devices and electronics

were unable to nd enough talent locally, they could

easily base their operations elsewhere—taking

thousands of working-class jobs on their assembly lines

with them. In 2015, immigrants made up one out of every

six workers employed in advanced manufacturing

in the region.

+P

7+M

FIGURE 15: THE OUTSIZE ROLE IMMIGRANTS PLAY AS STEM

WORKERS IN ADVANCED MANUFUCTURING IN THE GREAT

LAKES REGION, 2015

Foreign-Born

in the Great Lakes

Region

Share of STEM workers

in advanced manufacturing

16.2%

Share of the population

7.3%

New Americans and a New Direction | Manufacturing

20

This growth in the advanced

manufacturing industry has

been a lifeline for large numbers

of people in the working-class

as well. By 2015, almost 1.7

million working-class, U.S.-

born individuals held jobs in

advanced manufacturing. That

gure has been steadily rising:

Between 2010 and 2015, the

number of working-class jobs in

advanced manufacturing rose

by 9.6 percent. Of the more than

160,000 new jobs created during

that period for workers with less

than a bachelor’s degree, more

than nine out of every 10 were

lled by workers born in the

United States.

Although much of our research

focus was on the role foreign-

born workers play lling

high-skilled labor gaps in

the manufacturing industry,

it is important to note that

immigrants play an important

role at the other end of the skills

spectrum as well. Although

the vast majority of jobs

created for the working-class in

manufacturing have gone to U.S.-

born workers, as we discussed

above, many employers turn

to foreign-born workers to ll

jobs that often hold less appeal

for the U.S.-born. One prime

example is in the meatpacking

industry, a lesser known subset

of the manufacturing industry,

which can involve notoriously

physical and bloody work. In

2015, foreign-born workers made

up 30.7 percent of workers in

the animal slaughtering and

One beneficiary of the advanced

manufacturing economy—and its

critical need for workers—is Robert

Henning, an industrial spray painter

from Michigan who easily found work

after retraining in middle age.

Henning had been having trouble

getting a job, despite decades of

experience at manufacturers like

Milwaukee Sign Company and of-

fice-furniture giant Steelcase, both of

which experienced employee reorga-

nizations. He was 53, a high-school

dropout, and had been unemployed

for years due to complications follow-

ing a kidney transplant. Plus, plenty

of young, healthy workers were willing

to paint for only $12 per hour, signifi-

cantly less than the $20 per hour he’d

last earned.

Then he heard about a retraining program at Grand Rapids Community

College. “I felt healthy and I felt I had skills and I wanted to contribute,”

Henning says. So, he began a long process to become eligible for the program,

first earning his GED and then proving he had valuable workplace skills

by passing an assessment known as the ACT WorkKeys. Then he applied

and gained admission. Funded by the Michigan Coalition for Advanced

Manufacturing, the full-time, one-semester course taught him the algebra,

computing, and machining skills needed for a career in Computer Numerical

Control (CNC) Machining, a job with a projected growth rate of 18.9 percent

from 2014 to 2024.

26

Henning had his pick of several jobs before even

graduating. “I was really surprised,” he says.

Henning now works as a CNC Machinist at Pioneer Steel, where he operates

precision automated machinery that makes die sets for automotive manu-

facturers. He’s still in training, but expects to be earning $18 to $22 per hour

within one or two years with good benefits and ongoing room for growth.

“Every day I learn more,” he says. “I like coming to work.” For the first time in

years, he feels secure. “I feel I have marketable skills and I can possibly not

worry about retirement as much,” he says. “I feel very fortunate. I have a

second chance.”

Robert Henning

SPOTLIGHT ON

Computer Numerical Control Machinist

at Pioneer Steel

New Americans and a New Direction | Manufacturing

21

processing industry, despite making up just 7.3 percent

of the region’s population overall. In some of the most

labor-intensive positions within that industry, they

played a particularly outsize role: 48.2 percent of all

butchers and meat cutters in the region are foreign-born,

as are 45.2 percent of those with packaging and lling

jobs, the ones who take raw meat and prepare it for

shipment and sale.

Brittany Hibma, a career counselor in the Minneapolis-

St. Paul metro area, has seen many of the large

employers in her area—Amazon, SkyChefs, and

-O Turkey, among them—come to rely on one

particular type of less-skilled manufacturing worker:

The thousands of refugees who have settled in the area

in recent years. Having come from countries where

many had few opportunities for education or lives

disrupted by turmoil, “the refugees we work with are

incredibly determined to do a good job, and to become

a valuable part of our society and community,” Hibma

explains. Eager to get their foot in the door at a U.S.

employer, many of her clients have taken on jobs that

rms would have struggled to ll otherwise. These

can include meatpacking jobs, janitorial work, or

manufacturing jobs on nights or weekends.

Hibma says that many refugees tend to stay in their

positions long term. This steady workforce has allowed

a whole host of employers, including Direct, a

leading direct mail operator, to remain in the area—a

decision that has implications for many working-class

Americans, from the truckers who transport their

products to the warehouse workers who help store

it. Hibma says it is hard to overstate how important

refugees have become. “I can think of several companies

in our area,” Hibma says, “that would probably struggle

to keep their doors open without them.”

FIGURE 16: THE OUTSIZE ROLE IMMIGRANTS PLAY IN ANIMAL SLAUGHTERING AND PROCESSING IN THE GREAT LAKES

REGION, 2015

Field workers

30.7%

foreign-born

Packagers & fillers

45.2%

foreign-born

Population

7.3%

foreign-

born

Butchers

48.2%

foreign-born

New Americans and a New Direction | Manufacturing

22

W

hile manufacturing is experiencing

somewhat of a resurgence in the Great

Lakes region, the local economy is much

dierent than it once was, with several other industries

emerging as the leading drivers of job growth. The most

prominent example among them is the region’s $255-

billion healthcare sector. Between 2000 and 2015, more

than four out of every ve new jobs created in the Great

Lakes region, or 80.3 percent, were healthcare positions.

That growth means that healthcare has now replaced

manufacturing as the leading employer in the Great

Lakes region, employing 5.5 million people in 2015.

As many cities across the region struggled with

deindustrialization in recent decades, they began to

expand their economy beyond their manufacturing

base; now, with a booming healthcare sector, their

eorts are paying o. In Figure 18, we list the metros in

the region with the fastest-growing healthcare industries.

In Cleveland, healthcare employment increased by 28.4

percent between 2000 and 2015, led by the expansion

of the world-renowned Cleveland Clinic. The University

of Pittsburgh Medical Center () has also embodied

the current economic shift: It has replaced U.S. Steel as

Pittsburgh’s top employer and moved its headquarters

to the iconic U.S. Steel Tower, the tallest building in

the city.

27

In some areas, such as Columbus, Ohio and

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, increases in healthcare jobs

have more than oset the declines in manufacturing

employment that occurred between 2000 and 2015.

Between 2000 and

2015, more than four

out of every five new

jobs created were

healthcare positions.

There are many factors—not all unique to the Great

Lakes region—that have made healthcare such a

powerful engine of economic development. Nationwide,

healthcare demand is rising rapidly, due to the aging of

the country’s 76 million baby boomers. What’s more, the

rate of the population that is uninsured dropped from

17.1 percent to 10.9 percent between late 2003 and 2016,

driving the demand for services up still further.

28

The

good news is, with its extensive network of hospitals and

educational institutions, the Great Lakes region is well

positioned to meet this demand. The region as a whole

added 1.4 million healthcare jobs from 2000 to 2015

alone.

This healthcare boom has been a blessing for the

working-class, particularly those born in the United

Healthcare

PART IV

FIGURE 17: HEALTHCARE EMPLOYS MORE WORKERS IN THE

GREAT LAKES REGION THAN MANUFACTURING, 2015

5.5M

Healthcare

5.2M

Manufacturing

New Americans and a New Direction | Healthcare

23

FIGURE 18: TOP TEN GREAT LAKES METROS WITH FASTEST GROWTH IN U.S.-BORN WORKING-CLASS EMPLOYMENT IN

HEALTHCARE, 2000-2015

35.2% — MILWAUKEE, WI

29.7% — MINNEAPOLIS, MNWI

31.6% — HARRISBURG, PA

29.3% — ROCHESTER, NY

28.4% — ALLENTOWN, PANJ

34.1% — COLUMBUS, OH

29.5% — CINCINNATI, OHKYIN

30.6% — GRAND RAPIDS, MI

28.5% — SYRACUSE, NY

23.7% — MADISON, WI

22.7% — THE GREAT LAKES REGION

Average Regional Growth

U.S.-Born Working-Class Healthcare Employment

Fastest Growing Metros

In some

areas, such as

Columbus, Ohio,

and Harrisburg,

Pennsylvania,

increases in

healthcare jobs

have more

than offset

the declines in

manufacturing

employment

that occurred

between 2000

and 2015.

1

3

7

9

4

8

10

2

6

5

24

New Americans and a New Direction | Healthcare

States. In 2015, about two-thirds

of all healthcare jobs in the

region were held by workers

with less than a bachelor’s

degree. Those jobs, which

included a range of positions

such as some nursing aides,

medical assistants, and

medical receptionists, were

overwhelmingly lled by U.S.-

born workers: They occupied

93.5 percent of all less-skilled

healthcare positions in 2015.

(See Figure 19.)

The number of healthcare

positions for workers with

less than a bachelor’s degree

in the Great Lakes region

also continues to grow

rapidly. Between 2000 and

2015, the region added more

than 680,000 working-class

healthcare jobs. Almost 84

percent of those positions—or

almost 571,000 of them—were

lled by workers born in America.

Despite the increase in the

number of working-class

people opting to pursue jobs

in healthcare, the region is

still facing a labor shortage.

Previous research by has

found that in the healthcare

sector, more open jobs were

advertised online in 2014 than

there were unemployed workers

available to ll them. This

trend held across every state in

the Great Lakes region, from

Wisconsin, where there were 9.3

healthcare jobs listed for every

one unemployed health worker,

to New York, where there were

Kevin Kuczma, a Pittsburgh native, is

one person who has taken advantage

of the surge in job creation in the

healthcare industry in recent years.

In 2012, at age 38, Kuczma found

himself downsized out of a job for

the third time since he joined the

workforce just after high school.

After his first layoff, Kuczma spent

eight years at a manufacturer of

mass transit vehicles — working

his way up from warehouse driver

to manager — before his employer

opted to move production facilities

overseas to better compete for

foreign buyers. Kuczma, classified

by the state as “displaced due to

foreign competition,” had to start

over again at the bottom at another

manufacturer. After seven years,

that company opted to combine

production facilities with another manufacturer, displacing him once again.

But Kuczma had an ace in the hole: After high school, he had spent several

years working as an EMT (Emergency Medical Technician), a job that requires

about four months of training. Now a friend who owned an ambulance

company called him, desperate for EMTs. Kuczma took the job and, while

working, spent 18 months studying full time at the Community College of

Allegheny County to become a paramedic, a position that would allow him

to provide more advanced levels of emergency care. It is a role currently in

high demand: Just as an aging population puts stress on ambulatory services,

paramedics themselves are retiring at a rapid rate. The United States

is projected to add 58,500 paramedic jobs between 2014 and 2024, a 24

percent growth rate that’s much faster than the average for all jobs.

29

Kuczma’s current hourly rate—between $14.50 and $16.50, excluding

overtime—is comparable to the rate he made as a warehouse manager. But

thanks to the nature of the job, he takes home twice the pay. Paramedics

work 16- and 24-hour shifts that typically include waiting, and sleeping, between

runs. “My job satisfaction is high,” he says. “I really enjoy the work I do.”

And, he says, the days of worrying about getting laid off are finally behind him.

“The one thing about being a paramedic is you’re almost always able to find a

job,” says Kuczma, now 43. “Basically, you just say, ‘I’m a paramedic,’ and you

get hired because demand is so high.”

Kevin Kuczma

SPOTLIGHT ON

Paramedic

New Americans and a New Direction | Healthcare

25

just 2.9.

30

Metropolitan areas have certainly not been

immune from such labor challenges. In 2013, there

were more than ve online job postings for positions in

Milwaukee and Minneapolis for every one unemployed

health worker there, and more than 3.5 online job

postings per worker in Cleveland and Detroit.

The level of labor challenge facing the region’s

healthcare sector can be gleaned from recent job

creation and wage trends in the industry. Between

2000 and 2015, the number of physicians and surgeons

employed in the Great Lakes region increased by

43.9 percent. At the same time, the average wage of

physicians and surgeons rose by 19.3 percent—the

sort of steep jump that often indicates that employers

are competing for a limited pool of talent. In this

environment, foreign-born doctors, all of whom have

years of medical training, often step in to ll persistent

labor gaps. Despite representing just 7.3 percent of the

region’s population, they made up more than one out of

every four physicians and surgeons in the region in 2015.

FIGURE 19: THE GROWING NUMBER OF WORKING-CLASS HEALTHCARE JOBS IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION, 2000-2015

2000

2015

2.5M

3.1M0.2M

0.1M

U.S. BORN

U.S. BORN

Foreign-born

U.S.-born

Working-Class Healthcare

Jobs Created

2000-2015

681,277

Share that went to U.S.-born:

83.8%

Share that went to foreign-born:

16.2%

The number of

healthcare positions

for working-class

Americans continues

to grow rapidly.

FIGURE 20: THE OUTSIZE ROLE IMMIGRANTS PLAY

AS PHYSICIANS AND SURGEONS IN THE GREAT LAKES

REGION, 2015

+P

7+M

Foreign-Born

in the Great Lakes

Region

Share of physicians and surgeons

27.0%

Share of the population

7.3%

Total number

of physicians

and surgeons:

182,267

New Americans and a New Direction | Healthcare

26

New Americans and a New Direction | Case Study: Healthcare in Cleveland

27

Healthcare in Cleveland

I

n 2000, Cleveland’s economic picture seemed dim.

For decades, materials manufacturing jobs had been

undergoing a slow and steady exodus. The city’s

population had also shrunk by almost half since its peak

in 1950. As one local editorial put it, Ohio was “mired

complacently in what has been labeled the old economy,

characterized by production-line manufacturing.”

31

In an eort to revitalize the city’s economy, a group

of local leaders drafted a plan to build a $200 million

cluster of medical research facilities. It was an ambitious

eort to take advantage of the research expertise that

already existed at Case Western Reserve University,

the Cleveland Clinic, and University Hospitals, a

leading nonprot healthcare system. But some feared it

would not succeed. One noted economist warned that

Cleveland would be entering the $600 billion biotech

industry too late to even “ll a piggybank.”

32

It took less than a decade, however, to prove such

economists wrong. Today, Cleveland is held up as a

model of how a region can reinvent its economy for the

21st-century by innovating around a single industry.

Biotech companies now choose to set up in Cleveland’s

1,600-acre Health-Tech Corridor to take advantage

of the area’s medical research expertise and related

manufacturing experience. And regional manufacturers

that once focused on designing auto parts now produce

medical parts instead—often with the help of former

factory workers who have retrained at local community

colleges.

Cleveland is held up as a model

of how a region can reinvent its

economy for the 21st century

by innovating around a

single industry.

Such developments are having a meaningful impact

on local job creation, particularly for the city’s

working-class. In 2015, the biomedical sector—an

industry that includes medical device manufacturing,

pharmaceuticals, and research and development—

CASE STUDY

An Economy Transforming:

New Americans and a New Direction | Case Study: Healthcare in Cleveland

28

employed more than 12,000 people in the metro area.

During a period when the overall employment of

working-class residents in the Cleveland metro area

declined, the number of working-class Americans with

jobs in the broader healthcare sector also rose by

15.6 percent.

Many bioscience entrepreneurs who have come to the

area say that immigrants have been a critical part of

their success. Dr. Hiroyuki Fujita, a Japanese immigrant,

founded a rm called Quality Electrodynamics () in

2006, after earning a physics PhD from Case Western

Reserve University. His company, which manufactures

radiofrequency coils for magnetic resonance imaging

() scanners, currently employs more than 160

people locally. Roughly 90 percent of ’s product is

exported, creating valuable international business links

for the city.

When Fujita formed the company, he recruited four of

his colleagues — engineers and business professionals

— to join him, most of whom were immigrants like

himself. Today, about one fth of Fujita’s employees are

immigrants in highly-skilled roles.

This highly skilled industry has created a wide variety of

employment opportunities. In addition to the research

scientists and engineers, about one third of ’s

employees work on the production line. The production

employees, an integral part of ’s success, are paid

competitively with benets. They receive on-the-job

training in all aspects of production, everything from

soldering and repairs to packaging and inventory.

The Cleveland metro area has also continued to

see an expansion of more traditional segments of

the healthcare industry. When it comes to jobs, the

healthcare sector is one of the fastest-growing industries

in Cleveland, and has overtaken manufacturing as

the largest jobs provider in the metro area. Within

the industry, hospitals loom large, providing roughly

40 percent of the metro area’s healthcare jobs. Here

immigrants once again play a huge role. Although

foreign-born residents comprised just 5.7 percent of

the population of metro Cleveland, they made up 30.1

percent of the area’s practicing physicians in 2015.

Having a full sta of physicians and thriving hospital

systems is good news for working-class Americans.

For every doctor at the Cleveland Clinic, there are 18

employees supporting that individual, according to

the clinic’s former Toby Cosgrove.

33

This includes

everyone from technicians and aides to campus shuttle

drivers and electricians, and doesn’t even take into

account the many more jobs that are created in other

industries. When those doctors and drivers regularly

spend money at a local coee shop, for instance, more

workers may be needed to serve them.

Having a full staff of physicians

and thriving hospital systems

is good news for working-

class Americans.

The positive developments in the healthcare sector

have contributed to a more optimistic mood in the

area. Venture capital rms and other investors have put

$2.3 billion into biomedical startups in Northeast Ohio

since 2003, and many expect the industry to continue

expanding.

34

Although the city is still losing overall

population, such declines have slowed dramatically.

35

And between 2000 and 2012, Cleveland’s percentage

gain of young college graduates—a demographic crucial

to the region’s growth—ranked the third largest in the

nation, besting Silicon Valley and Portland, Oregon.

36

Fujita, the founder, says he has an enormous

appreciation for the unique virtues of being based

in Mayeld Village, a near suburb of Cleveland that

is perfectly positioned in the Cleveland health-tech

corridor. As has grown over the last decade, the

company thrice moved to larger facilities. But Fujita

never considered leaving Mayeld Village. “Cleveland

is one of the meccas when it comes to the healthcare

industry,” he says. “The supply chain, the ecosystem,

it’s all here.”

As the healthcare sector has expanded in recent years,

it has also created some working-class jobs that have

been more dicult for employers to ll. These jobs can

include everything from home health aide positions,

which can be physically challenging with relatively

lower pay, as well as medical aides and technicians.

Immigrants have helped ll some of these jobs. As

nurses and home health aides, they provide care much

needed by the region’s seniors. Immigrants also help

ease the increasing shortage of psychiatrists, enhancing

the productivity of the region’s workers. One recent

study, for instance, nds that each month, Pennsylvania

alone has more than 163,000 days when its workers

suered from decreased productivity or missed days of

work due to inadequate mental healthcare.

37

Figure 21

shows more healthcare support occupations in which

immigrants have come to play a particularly a valuable

role.

The healthcare sector is expected to be the fastest-

expanding industry in the United States between 2014

and 2024, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

38

For the Great Lakes region to maintain its current

level of robust healthcare growth, it will need to both

retrain displaced manufacturing workers like Kuczma

and also rely on immigrants to meet the area’s real and

persistent labor needs. With their talent and hard work,

the more than 450,000 foreign-born workers employed

in healthcare in the region are not only improving the

quality of life of residents, but also helping the Great

Lakes region build up one of its most promising engines

of job growth as well.

FIGURE 21: TOP FIVE HEALTHCARE SUPPORT

OCCUPATIONS FOR IMMIGRANTS IN THE GREAT LAKES

REGION IN 2015

Nursing, Psychiatric, and Home Health Aides

Phlebotomists

Pharmacy Aides

Physical Therapist Assistants and Aides

Massage Therapists

6.6%

9.8%

9.3%

9.3%

7.1%

As the healthcare

sector has expanded

in recent years,

some working-class

jobs have been

more difficult to

fill. Immigrants have

helped with some of

these jobs.

Share of workers who are

foreign-born:

Healthcare

New Americans and a New Direction | Healthcare

29

T

he Great Lakes region’s deep agricultural

roots are reected by its millions of acres of

farmland, as well as its history of producing

well-known crops. Michigan has long held a leading role

producing fresh fruits and vegetables, including apples,

sugar beets, and blueberries.

39

Illinois and Indiana

are the country’s top exporters of corns and soybeans.

Wisconsin, also known as the Dairy State, is famed for

its milk and cheese.

40

Overall, agriculture is a critical

part of the economic landscape in the Great Lakes states,

contributing at least $25 billion to the region’s Gross

Domestic Product () in 2015 alone.

41