Occasional Paper Series

Stablecoins:

Implications for monetary policy,

financial stability, market

infrastructure and payments, and

banking supervision in the euro area

ECB Crypto-Assets Task Force

No 247 / September 2020

Disclaimer: This paper should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB).

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

1

Contents

Abstract 2

Executive summary 3

1 Introduction 5

2 Characterisation of stablecoins 7

3 Recent developments and current status of stablecoins 11

4 Risk asse ssment 17

4.1 Monetary policy 19

4.2 Financial stability 22

4.3 Market infrastructures and payments 23

4.4 Banking supervision and prudential regulation 27

5 Conclusions 31

References 33

Acknowledgements 35

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

2

Abstract

This paper summarises the outcome of an analysis of stablecoins undertaken by the

ECB Crypto-Assets Task Force. At the time of writing, the stablecoin debate lacks a

common taxonomy and unambiguous terminology. This paper applies a definition that

distinguishes stablecoins from existing forms of currencies – regardless of the

technology used – and characterises stablecoin arrangements based on the functions

they fulfil. This approach emphasises the role of technology-neutral regulation in

preventing arbitrage, as well as comprehensive Eurosystem oversight, irrespective of

stablecoins’ regulatory status. Against this background, this paper assesses

stablecoins’ implications for the euro area based on three scenarios for the uptake of

stablecoins: (i) as a crypto-assets accessory function; (ii) as a new payment method;

and (iii) as an alternative store of value. While the first scenario is merely the

continuation of the current state of the market and, thus far, has not posed concerns

for the financial sector and/or central bank tasks, stablecoins of the type envisaged in

the second scenario may reach a scale such that financial stability risks can become

material, and the safety and efficiency of the payment system may be affected. The

third scenario is both the least plausible and the most relevant from a monetary policy

perspective. The paper concludes that the Eurosystem relies on appropriate

regulation, oversight, and supervision to manage the implications of stablecoins (and

the risks that stem from them) on its mandate and tasks under plausible scenarios.

The Eurosystem continues monitoring the evolution of the stablecoin market and

stands ready to respond to rapid changes in all possible scenarios.

Keywords: stablecoins, implications of stablecoins, regulation, oversight

JEL codes: E42, G21, G23, O33

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

3

Executive summary

“Stablecoins” are a relatively recent payment innovation, which has already

been the subject of much debate – particularly in the last year. Initially,

terminology can be a confusing, even misleading, element in the discussion

surrounding new technological phenomena. This report builds on an earlier definition

of stablecoins as digital units of value that differ from existing forms of currencies (e.g.

deposits, e-money, etc.) and rely on a set of stabilisation tools to minimise fluctuations

in their price against a currency, or basket thereof.

1

Different types of stablecoins have

emerged.

2

To maintain a stable price, some stablecoin initiatives pledge to hold funds

and/or other assets (“collateral”) against which stablecoin holdings may be redeemed

or exchanged. Stablecoin arrangements fulfil multiple functions: from the stabilisation

of the value of stablecoins to the transfer of value, and interaction with users.

Recent initiatives may stimulate the adoption of stablecoins and raise

implications for public policy, regulation, oversight and supervision. The extent

of these implications will depend on the specific scenario for the uptake of stablecoins.

This article identifies three such scenarios. Stablecoins could have a “crypto-assets

accessory function” that allow securing crypto-asset revenues in less volatile assets

without leaving the crypto-ecosystem (first scenario), or become a “new payment

method” (second scenario), or even an “alternative store of value” (third scenario).

These scenarios depend on the specific features of stablecoins – the second and third

scenarios are reliant on stablecoin types that offer high levels of price stability and

credible redemption policies – and on key drivers for their adoption (e.g. convenience

and ease of use as compared to existing instruments).

This analysis shows that a stablecoin arrangement of the type entailed in the

second scenario (“new payment method”) could reach a scale of operations

such that fragilities within the stablecoin arrangement itself, and its links to the

financial system, may give rise to financial stability risks. Stablecoins are

vulnerable to liquidity “runs”. Where a stablecoin is exchanged/redeemed at the

market value of its collateral, a run could occur if end users are confronted with the

prospect that the stablecoin’s collateral may lose its value. Runs could also occur in

the case of an arrangement that guarantees redeemability at face value – if the

stablecoin sponsor is perceived as lacking sufficient loss-absorbing capacity. In these

events, the liquidation of assets to cover redemptions could have negative contagion

effects on the financial system.

As part of their transfer of value function, stablecoins can also have

implications for the safety and efficiency of payment systems and, under

certain conditions, even pose systemic risk. The specific sources of risks and

inefficiencies would depend on the design of the transfer of value system, ranging from

the legal basis to governance (especially in a highly decentralised arrangement), the

1

See Bullmann et al. (2019).

2

See European Central Bank (2019).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

4

arrangement’s choice of settlement asset, operational complexities and, among other

things, cyber risks.

Euro deposits and cash are expected to be resilient to the possible advent of an

“alternative store of value”. In the event that this less plausible “alternative store of

value” scenario materialises, significant implications for monetary policy could arise.

This scenario involves stablecoin types that hold safe assets as collateral to achieve

high levels of stability of the stablecoin’s value. Their significant uptake could increase

demand for safe assets by stablecoin arrangements and might have a negative impact

on price formation, collateral valuation, money market functioning and the monetary

policy space. Banks’ intermediation capacity might also be challenged. That being

said, the current negative interest rate environment could place significant constraints

on the profitability of a non-interest-bearing stablecoin, as its collateral would be

remunerated negatively.

The Eurosystem can use a range of tools to manage the implications of

stablecoins in plausible scenarios. The Eurosystem’s oversight framework will

cover stablecoin arrangements that qualify as payment systems regardless of the

technology used and their organisational setup. Furthermore, the Eurosystem is

reviewing its oversight framework for payment instruments and schemes, with a view

to broadening its scope to include any electronic payment instruments that enable end

users to send and receive value, including based on stablecoins. The Single

Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) can rely on the existing approach for supervision and

require banks to put in place an appropriate risk management framework for

addressing risks resulting from their potential involvement in stablecoin

arrangements/ecosystems.

These efforts need to be complemented by adequate, internationally

coordinated regulation and cooperative oversight and supervision. The

European Union (EU) and Eurosystem regulatory and oversight response should

follow the principle of “same business, same risks, same rules” to ensure a level

playing field by applying existing requirements as appropriate and closing gaps (e.g.

through suitable prudential requirements for large stablecoin issuers) in a manner

consistent with the guidance of international standard setting bodies. Appropriate

accounting and prudential treatments should be identified in a timely fashion.

Overseers and supervisors should strengthen cooperation arrangements in the light of

ecosystems spanning multiple jurisdictions.

The Eurosystem continues to monitor the evolution of the stablecoins market

and stands ready to respond to rapid changes in all possible scenarios. Current

initiatives could alter the European payments landscape and may exacerbate

Europe’s dependence on global players in the field of payments. This may call for, inter

alia, fostering central bank innovations to cater for a changed environment in the

payments space and altered conditions for the exercise of a central bank’s core

mandate.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

5

1 Introduction

The ECB Internal Crypto-Assets Task Force (ICA-TF) was established in 2018

with a mandate to deepen the analysis around virtual currencies and

crypto-assets. The ICA-TF analysis focuses on assessing and identifying how to

contain any adverse impacts of crypto-assets on the use of the euro, the Eurosystem’s

monetary policy, the safety and efficiency of financial market infrastructures and

payments, and the stability of the financial system. This analysis serves as a basis for

European Central Bank (ECB) contributions to policy discussions in the European

System of Central Banks (ESCB), the EU and other international fora, and with the

relevant regulatory authorities. The Occasional Paper

3

published in May 2019

summarises the ICA-TF analysis on crypto-assets. Since then, the ICA-TF has been

monitoring market developments with a view to keeping this assessment up to date.

While stablecoins are not a new development – the currently most traded

stablecoin dates back to 2014 – recent initiatives have brought about a

paradigm shift in the public debate on stablecoins. In particular, the

announcement of one such initiative – Libra – in June 2019 triggered a

globally-coordinated response under the umbrella of the G7. The G7 working group

report on the impact of global stablecoins was published in October 2019.

4

From then

on, the G20, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), and several standard setting bodies

have also embarked on efforts to address the potential risks while harnessing the

potential of technological innovation.

5

The ECB participates in these efforts via the

relevant fora. In December 2019 the Council and the European Commission released

a joint statement on stablecoins, calling for a coordinated approach to tackling the

challenges raised by global stablecoins, and swift action on the part of the relevant

authorities in cooperation with the ECB.

6

Building on ongoing work at the international level and leveraging its

crypto-asset analytical framework, the ICA-TF has analysed stablecoins with a

view to identifying their potential implications for the Eurosystem’s monetary

policy, as well as euro area financial stability, market infrastructure and

payments, and banking supervision. This analysis is not intended as an evaluation

of the merits of stablecoins versus their drawbacks, but rather serves as a contribution

to the development of a safe environment for innovations in payments and financial

services.

This paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a characterisation of

stablecoins and stablecoin arrangements. Section 3 summarises recent

developments and current status of stablecoin markets. Then, Section 4 provides an

assessment of stablecoins’ implications, covering monetary policy, financial stability,

3

See ECB Crypto-Asse ts Task Force (2019).

4

G7 Working Group on Stablecoins (2019).

5

See Financial Stability Board (2020).

6

See Council of the European Union (2019).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

6

market infrastructure and payment dimensions, as well as the banking supervision

and prudential regulation perspective. Section 5 concludes.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

7

2 Characterisation of stablecoins

Stablecoins can be generally defined as digital units of value that are not a form

of any specific currency, or basket thereof, and that rely on a set of stabilisation

tools to minimise fluctuations of their price against such currency, or

currencies.

7

To maintain a stable price against the currency, or currencies, of

reference, some stablecoins pledge to hold funds and/or other assets (“collateral”)

against which stablecoin holdings can be redeemed. Alternatively, stablecoins rely on

a mechanism that attempts to match demand and supply so as to maintain parity

between the stablecoin and the reference currency, or currencies, and to guide users’

expectations on its future value (algorithmic stablecoins). An element common to all

stablecoin initiatives is their reliance on an open market to reinstitute par value by

providing arbitrage opportunities. Stablecoin arrangements fulfil multiple functions

including the stabilisation of the value of stablecoins, the transfer of stablecoins and

the facilitation of the interaction with the users via a dedicated interface.

8

Existing forms of currencies and other traditional assets that use innovative

technologies are not the focus of this analysis. Examples include e-money and

commercial bank deposits recorded by means of distributed ledger technology (DLT),

which nevertheless may be marketed as stablecoins. Wholesale digital tokens for the

settlement of large-value transactions between institutions (usually banks), which

represent an existing claim, either on a specific issuer or on underlying assets or

funds, or some other right or interest

9

– and often referred to as stablecoins – are not

addressed in this paper. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are also excluded

from the scope of this analysis insofar as they are a liability of the central bank.

Based on their design, stablecoins have been classified into four types: (i)

tokenised funds

10

; (ii) off-chain collateralised stablecoins; (iii) on-chain

collateralised stablecoins; and (iv) algorithmic stablecoins.

11

Table 1

summarises the main characteristics of each stablecoin type. Stablecoins can also be

distinguished on the basis of their geographic scope, whereby “global” stablecoins

would encompass multiple jurisdictions in terms of their users, the entities comprising

the arrangement, and the composition of the collateral (if relevant).

7

See Bullmann et al. (2019).

8

See G7 Working Group on Stablecoins (2019).

9

See CPMI, Wholesale digital tokens, December 2019.

10

The term “tokenised funds” is borrowed from Bullmann et al. (2019) and is used here without prejudice to

the competent authorities’ determination of applicable law, i.e. whether or not the initiative can be

qualified as funds in the meaning of the Revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2). In practice, as

noted later in this paper, these initiatives share several features of supervised or overseen payment

instruments, payment schemes and payment systems.

11

Bullmann et al. (2019).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

8

Table 1

Summary table of stablecoin characteristics

issued on the receipt of: “collateralised” by: redeemable at:

Tokenised

funds

funds (i.e. cash, deposits or

electronic money)

funds and/or close substitutes (i.e.

secure, low-risk, liquid assets

12

)

market value of the collateral at the

time of redemption or face value of

the stablecoin

Off-chain

collateralised

stablecoin

assets held through an accountable

entity (e.g. securities, commodities,

or crypto-assets in custody with an

intermediary)

assets held through an accountable

entity (e.g. securities, commodities,

or crypto-assets in custody with an

intermediary)

market value of the collateral at the

time of redemption

On-chain

collateralised

stablecoin

cr ypto-assets held directly on the

distributed ledger

cr ypto-assets held directly on the

distributed ledger

market value of the collateral at the

time of redemption

Algorithmic

stablecoins

cr ypto-assets or given away for free no collateral – value of stablecoin is

based purely on the expectation of

its future market value

not redeemable

Source: Based on Bullmann et al. (2019).

Notes: Some stablecoin initiatives add to the pool of collateral own funds, which are raised through either fees or margin calls.

Redemptions are subject to the conditions set out in the stablecoin’s terms of service. For the purposes of this table, only voluntary

redemption is considered. Compulsory redemption occurs when the value of the collateral for a stablecoin unit drops below the level

specified within the rules of the stablecoin initiative.

Most stablecoins currently in operation (see also Section 3) do not share the

most prominent characteristic of crypto-assets, which is the absence of a

financial claim on, liability of, or proprietary right against any identifiable

entity.

13

In fact, tokenised funds and off-chain collateralised stablecoins necessitate

an accountable issuer that is responsible for safekeeping of the collateral, either

directly or through a custody agreement with a third-party, and can therefore be held to

account for satisfying holders’ rights.

Stablecoins that entail a claim/liability on an identifiable entity (which are not

crypto-assets as per the ECB definition) should be subject to existing

regulatory standards, as amended, to impose additional requirements where

needed.

14

Some initiatives in tokenised funds share the function and characteristics of

e-money but the application of the Electronic Money Directive (EMD2)

15

may be

insufficient on its own to address increased complexities and risks of stablecoin

business models. The application of EU investment fund regulation is also premised

on the condition that the investment fund share represents a claim of its holder on the

investment fund’s assets

16

. Otherwise the issuer would not be bound by the standard

EU regulatory framework of Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable

12

See, for example, Table 1 of Point 14 of Annex I to Directive 2006/49/EC of the European Parliament and

of the Council of 14 June 2006 on the capital adequacy of investment firms and credit institutions (OJ

L 177, 30.6.2006, p. 201).

13

See ECB Crypto-assets Task Force (2019).

14

See European System of Central Banks (2020).

15

Directive 2009/110/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 September 2009 on the

taking up, pursuit and prudential supervision of the business of electronic money institutions amending

Directives 2005/60/EC and 2006/48/EC and repealing Directive 2000/46/EC (OJ L 267, 10.10.2009,

p. 7). See Article 2.2 “‘electronic money’ means electronically, including magnetically, stored monetary

value as represented by a claim on the issuer which is issued on receipt of funds for the purpose of

making payment transactions as defined in Point 5 of Article 4 of Directive 2007/64/EC, and which is

accepted by a natural or legal person other than the electronic money issuer”. See also EBA (2019a),

which outlines the circumstance in which assets will qualify as electronic money and will therefore fall

within the scope of the EMD2.

16

See Adachi et al. (2020).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

9

Securities

17

or Alternative Investment Fund Managers (AIFM)

18

, or by the regulation

of Money Market Funds.

19

Irrespective of the regulatory treatment of stablecoins, the function of

stablecoin arrangements that caters for the execution of transfer orders may

qualify as “payment system” for the purposes of Eurosystem oversight. The

ECB Regulation on oversight requirements for systemically important payment

systems

20

(SIPS Regulation) defines a payment system as “a formal arrangement

between three or more participants, […] with common rules and standardised

arrangements for the execution of transfer orders between the participants”. Within

this definition, transfer order and participants are defined in broad terms that allow

accommodation of “any instruction which results in the assumption or discharge of a

payment obligation” (Article 2(i) of the Settlement Finality Directive

21

) and any “entity

that is identified or recognised by a payment system and, either directly or indirectly, is

allowed to send transfer orders to that system and is capable of receiving transfer

orders from it” (Article 2 (18) of SIPS Regulation), respectively. To the extent that

stablecoin arrangements qualify as payment systems, the Eurosystem payment

system oversight framework based on the Principles for Financial Market

Infrastructures (PFMI) of the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures

(CPMI) and the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO)

22

would apply.

Similarly, the function of stablecoin arrangements that sets standardised and

common rules for the execution of payment transactions between end users

could qualify as a “payment scheme”. Where stablecoins are denominated in,

funded by or collateralised by euro, the governance body that is responsible for the

overall functioning of the payment scheme might be subject to the revised and

consolidated Eurosystem oversight framework for payment instruments and schemes.

This framework, which is currently under development, would be applicable to any

electronic payment instruments that enable end users to send and receive value, and

hence would apply irrespective of the qualification of the asset as funds under the

Revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2).

23

Furthermore, individual entities comprising a stablecoin arrangement’s

ecosystem could take up activities to offer services or products that may well

be subject to licensing regimes under EU or national law. Depending on the

17

Directive 2009/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 on the coordination

of laws, regulations and administrative provisions relating to undertakings for collective investment in

transferable securities (UCITS) (OJ L 302, 17.11.2009, p. 32).

18

See Directive 2011/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on Alternative

Investment Fund Managers and amending Directives 2003/41/EC and 2009/65/EC and Regulations (EC)

No 1060/2009 and (EU) No 1095/2010 (OJ L 174, 1.7.2011, p. 1).

19

See Regulation (EU) 2017/1131 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2017 on

money market funds (OJ L 169, 30.6.2017, p. 8).

20

Regulation of the European Central Bank (EU) No 795/2014 of 3 July 2014 on oversight requirements for

systemically important payment systems (ECB/2014/28) (OJ L 217, 23.07.2014, p.16).

21

Directive 98/26/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 1998 on settlement finality

in payment and securities settlement systems, (OJ L 166, 11.6.1998, p. 45).

22

See Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and the International Organisation of Securities

Commissions (2012).

23

See footnote 9.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

10

products they offer, and the services they provide, several legal and regulatory

regimes could apply to them (including MiFID2

24

, PSD2, AIFMD, etc.). The entire set

of applicable frameworks could only be identified on a case-by-case basis.

Stablecoin arrangements should be subject to relevant regulation, oversight,

and supervision across all relevant functions. Efforts are underway in the EU to

examine the applicability of existing rules and evaluate the need for new legislation as

appropriate. These efforts should prioritise substance over form and apply the same

rules to all activities that give rise to the same risks, irrespective of the technologies

used or the type of service provider/operator. Furthermore, regulation, oversight and

supervision should cover all relevant functions comprising a stablecoin ecosystem,

including those that are not governed by a stablecoin’s issuer or scheme manager.

Finally, given the cross-border nature of stablecoin arrangements, international

coordination is crucial to ensure consistency and prevent regulatory arbitrage.

24

Directive 2014/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on markets in

financial instruments and amending Directive 2002/92/EC and Directive 2011/61/EU (OJ L 173,

12.6.2014, p. 349).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

11

3 Recent developments and current status

of stablecoins

A growing number of stablecoin initiatives have been reported in the last few

years especially since 2018: of these, 50 are currently traded on crypto-asset

trading platforms.

25 26

Most traded stablecoins were launched in 2018 (around 40%)

while those that started to trade this year account for 16% of all traded stablecoins.

Tokenised funds are estimated to be the most numerous stablecoin type, followed by

on-chain collateral and algorithmic

27

. Europe, including the United Kingdom and

Switzerland, hosts a third of traded stablecoins, whereas a quarter have their

headquarters in the euro area. Stablecoin market dynamism is also evidenced by a

relatively high number of reportedly closed initiatives.

28

Stablecoins trade at levels comparable to those of bitcoin – the most prominent

crypto-asset – with Tether, a stablecoin, in a dominant position (see Chart 1).

Trading volumes of stablecoins

29

showed dynamic increases since spring 2019,

driven by the release of the initial Libra White Paper. However, by mid-2020 they

returned broadly to pre-Libra levels. Trading volumes peaked again in 2020, following

the outbreak of the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis and related financial market and

crypto-asset turbulences including a bitcoin price nosedive which led investors to turn

to stablecoins.

25

Blockdata (2019) reports about 134 project announcements as of 2019.

26

Number currently being traded on crypto-asset trading platforms based on information retrieved from

Coinmarketcap.

27

See also Bullmann et al. (2019).

28

Blockdata (2019) reports 26 initiatives closed (i.e. no longer operational) as of 2019.

29

Trading volumes provide a partial measure of the use of the stablecoins generally intended as a means of

exchange in the real economy. Data on the use of stablecoins for retail payments are not currently

available.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

12

Chart 1

Trading volumes

(USD billion, Jan. 2018 – June 2020, end-of-month data)

Sources: Cr yptocompare and ECB calculations.

Notes: The coverage included on the chart is as follows: major crypto-assets: BCH (bitcoin cash), BTC (bitcoin), EOS (Eos), ETH

(Ethereum), XLM (Stellar), XRP (Ripple) and major stablecoins: DAI (Dai coin), GUSD (Gemini Dollar), PAX (Paxos Standard), TUSD

(TrueUSD), USDC (USD coin) and USDT (Tether).

Trading data confirms earlier findings that the prevalent use case of stablecoins

is to provide a store of value for revenues related to crypto-asset investments.

Trades of Tether versus those of crypto-assets, and especially versus those of bitcoin,

constitute the vast majority of all trades, while trades of Tether versus those of other

stablecoins and fiat currencies are very small (see Chart 2). Although most

stablecoins are referenced to international fiat currencies of USD, EUR, GBP, or

baskets thereof, the volumes of direct trades of stablecoins versus those of fiat

currencies are insignificant, which further supports the aforementioned observation

regarding the original stablecoin function.

Chart 2

Trading volumes of Tether vis-à-vis crypto-assets and fiat currencies

(percentages, Jan. 2018 – June 2020, end-of-month data)

Sources: Cryptocompare and ECB calculations.

Note: For coverage see Chart 1.

-

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

01/18 04/18 07/18 10/18 01/19 04/19 07/19 10/19 01/20 04/20

Major crypto-assets

BTC (bitcoin)

Major stablecoins

USDT (Tether)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

01/18 04/18 07/18 10/18 01/19 04/19 07/19 10/19 01/20 04/20

BTC (bitcoin)

Other major crypto-assets

Major stablecoins

Selected fiat currencies

Other

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

13

Market capitalisation of major stablecoins represents a fraction (6.5%) of that of

bitcoin, however it increased multi-fold only in 2020. The driver behind the

increased market capitalisation was a growing supply of stablecoins, which has almost

tripled for Gemini USD and more than doubled for Tether, USD Coin and DAI since the

beginning of 2020 (see Chart 3). The increased supply might have resulted from

higher demand from investors amid the start of the COVID-19 crisis.

30

Chart 3

Market capitalisation

(USD billion and percentage, Jan. 2018 – 12 July 2020, daily data)

Sources: Coinmarketcap and ECB calculations.

Note: See Chart 1 for names of the stablecoins.

With respect to prices, the volatility of stablecoin prices is less pronounced

than that of popular crypto-assets (see Chart 4). The price volatility varies across

stablecoin types, with tokenised funds showing the lowest volatility. Price volatility of

both stablecoins and crypto-assets peaked in the first quarter of 2020, while the price

volatility of the latter decreased afterwards to the lowest levels since 2019. Price

volatility for stablecoins also decreased, although to a lesser degree. Increased

volatility for some stablecoins may suggest difficulties in competing against other

dominant stablecoins and also vulnerabilities of stablecoin design.

30

See, for example, Coin Metrics (2020).

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

01/19 02/19 03/19 04/19 05/19 06/19 07/19 08/19 09/19 10/19 11/19 12/19 01/20 02/20 03/20 04/20 05/20 06/20

USDT

PAX

GUSD

TUSD

USDC

DAI

BUSD

HUSD

Compared to market capitalisation of bitcoin (right-hand scale)

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

14

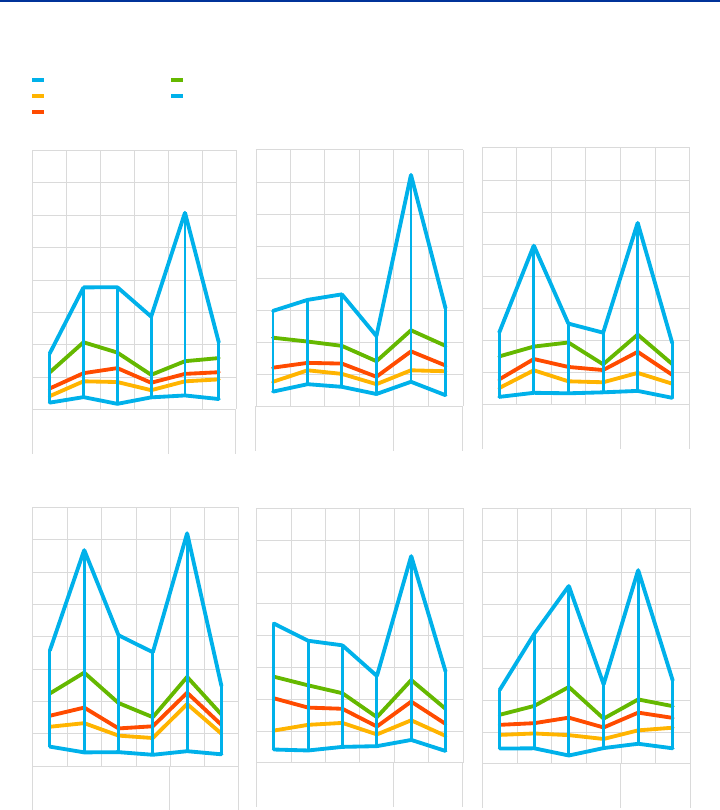

Chart 4

Price volatility

Selected non-stablecoin crypto-assets

(1 Jan. 2019 – 30 June 2020)

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

BTC

Minimum

1st quartile

Median

3rd quartile

Maximum

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

ETH

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

XRP

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

BCH

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

EOS

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

XLM

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

15

Stablecoins

(1 Jan. 2019 – 30 June 2020)

Sources: Coinmarketcap and ECB calculations.

Notes: Volatility is measured as the standard deviation of day-to-day per cent changes of rolling seven day windows. Volatility is

annualised. Coverage of crypto-asset as in Chart 1.

Insights into the current linkages of stablecoins with the real economy and the

financial system are hindered by a lack of data. In general, crypto-assets and

related technology draw significant public and media attention. Looking at “alternative”

data sources, the Google Trends indicators point to significant traffic generated by the

searches of terms related to crypto-assets with growing interest in stablecoins (see

Chart 5). Turning to the reach of stablecoin initiatives via Twitter, a few hundred

thousand follow the accounts of stablecoins, with more than 100,000 followers of

Gemini Dollar. Tether and the MakerDAO have 40,000 and 47,700 followers,

respectively.

31

31

Data collected on 27 July 2020.

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

USDT

Minimum

1st quartile

Median

3rd quartile

Maximum

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

PAX

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

GUSD

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

TUSD

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

USDC

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2019 2020

DAI

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

16

Chart 5

Interest in crypto-assets and related searches

(interest over time, collected on 13 July 2020, weekly data)

Source: Google Trends.

Notes: Interest over time represents search interest worldwide relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A

value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means there was not

enough data for this term.

The current status of the market might change significantly as a result of new

stablecoin initiatives that purport to provide efficient means of payment for

mainstream use cases (e.g. international remittances, cash transfer

programmes, international consumer-to-business payments). Furthermore, the

involvement of large technology and consumer companies with vast user bases (as in

the case of Libra) provides a natural platform for a more significant uptake of

stablecoins.

32

32

The Libra Association is progressing swiftly on technical design and development and has recently

unveiled a revised whitepaper – see Libra Association (2020). The Libra Association proposes to offer

single-currency stablecoins, in addition to a multi-currency Libra, and to tighten access to the Libra

network, among other things. It also submitted a formal application for a payment system licence under

the Swiss Financial Market Infrastructure Act to the Financial Markets Supervisory Authority.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

01/2017 05/2017 09/2017 01/2018 05/2018 09/2018 01/2019 05/2019 09/2019 01/2020 05/2020

Bitcoin

Tether

Blockchain

Stablecoin

Cryptocurrency

Facebook libra

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

17

4 Risk assessment

This section aims to illustrate the potential impact of stablecoins on the

Eurosystem’s ability to set the monetary policy stance, maintain financial

stability, ensure the safety and efficiency of market infrastructures and

payments, and for the conduct of banking supervision.

Based on stablecoins currently in operation (see Section 3), a risk assessme nt

would, in principle, not significantly differ from the current ECB stance on

crypto-assets

33

, but may change substantially in the light of emerging

stablecoin initiatives. The current market capitalisation does not give rise to

concerns with regard to the financial stability of the euro area. There is a shortage of

data on interlinkages between stablecoins and the financial system but overall EU

financial institutions have been applying the same conservative approach as is applied

to exposures to crypto-assets. There is limited evidence of existing stablecoins being

used for payments outside of the crypto-assets market. Therefore, at the moment, the

implications of stablecoins for economic developments and monetary policy would be

as negligible as those of crypto-assets. However, emerging initiatives have the

potential to provide attractive means of payment and possibly store of value

alternatives that can scale up rapidly and become ingrained in the payment habits of

EU consumers and businesses.

Stablecoin features play a critical role in influencing the uptake of stablecoins

as means of payment and/or store of value, which in turn determine the

concrete implications for monetary policy, financial stability, and market

infrastructures and payments. As mentioned in Section 2, stablecoins may differ

based on their design including, inter alia, levels of price stability vis-à-vis fiat

currencies and the conditions for their redemption. In addition to these features, there

are several factors that may drive user adoption of stablecoins as means of payment

and/or store of value. Three scenarios

34

for the potential use of stablecoins can be

discerned, the second and third of which are reliant on stablecoin types that offer high

levels of price stability and credible redemption policies:

• “crypto-assets accessory function”: stablecoins that lack the (perceived)

safety and ease of use to compete with established payment means for

mainstream use cases continue to cater mostly for the crypto-asset market

or specific user needs;

• “new payment method”: stablecoins that are convenient, easy to use and

also cater for payment use cases and user segments that are typically

underserved by existing solutions (e.g. cross-border payments) and at the

same time appear to mitigate the main perceived risks (e.g. loss of funds,

fraud), becoming an ordinary means of payment;

33

See ECB Crypto-Assets Task Force (2019).

34

These scenarios are simplified representations of possible future developments.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

18

• “alternative store of value”: stablecoins that satisfy user demand for a

cheap store of value through (more) attractive remuneration rates and are

sponsored by reputable institutions, and may therefore lead their users to

replace (part of) their euro deposits and cash with stablecoins.

A fourth scenario could be considered in which the central bank issues a CBDC

with technical and functional features similar to those of stablecoins, making

their value proposition redundant (at least for domestic payments) and

delivering the highest level of stability for users in a monetary jurisdiction. The

current paper does not elaborate on this scenario. The possibility of issuing a digital

euro, including in relation to the risks associated with stablecoins, and its specific

features, is currently being analysed by a Eurosystem high-level task force. In parallel,

several central banks (e.g. Sveriges Riksbank, Bank of Canada, People’s Bank of

China) are conducting practical experimentation – mainly through Proofs of Concept –

to explore the technical feasibility and the domestic and international implications of

issuing CBDC.

The first scenario is essentially the continuation of the current state of the

market, whereas the second and third scenarios are premised on future

developments changing the stablecoins landscape. Under the second scenario,

notwithstanding the progress made so far in enhancing euro payments, stablecoin

initiatives could exploit certain weaknesses or gaps (e.g. lagging instant payments

deployment and uptake, slow and costly cross-currency payments) and built-in

advantages to compete with existing electronic means of payment. A large-scale

substitution under the third scenario is less likely to materialise in situations where

confidence in the regulated financial system and financial regulators is high.

Furthermore, under certain constraints such as negative interest rates, this scenario

would be even more remote if the stablecoin initiative invested (mostly or solely) in

negatively remunerated safe assets and were to pass on the negative remuneration of

reserve assets to users (see Section 4.1.1). That said, variants of this scenario cannot

be ruled out in other economies, in which case there could be spill-overs to the euro

area.

35

The following sections of this report aim at illustrating the impact of stablecoins, in the

second and third scenarios, on the Eurosystem’s ability to set the monetary policy

stance for the euro area (Section 4.1), maintain financial stability (Section 4.2), and

ensure the safety and efficiency of financial market infrastructures and payments

(Section 4.3). Finally, Section 4.4 addresses aspects related to banking supervision

and prudential regulation.

35

Using the Libra project as an example, Adachi et al. (2020) provides estimates of the potential size of a

stablecoin arrangement. The Libra Reserve’s total assets under management could range from

€153 billion, when Libra coin is mostly used as a means of payment, to around €3 trillion, if it becomes a

widely adopted store of value under extreme assumptions.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

19

4.1 Monetary policy

A hypothetical situation in which stablecoins become an “alternative store of

value” (the third scenario described above) would have consequences for the

transmission of monetary policy and other related issues.

4.1.1 Policy constraints

A non-interest-bearing stablecoin could in principle set a zero effective lower

bound on policy rates. Widespread investment into non-interest-bearing stablecoins

could induce substitution out of assets yielding negative interest to the point where

further cuts in key policy rates no longer transmit to other interest rates in the

economy. Such shifts are, however, unlikely to occur in a negative interest rate

environment. To be able to offer a zero interest rate on a sustained basis, stablecoin

initiatives would have to charge fees to avoid significant losses or alternatively they

would have to cross-subsidise the issuance of stablecoins because collateralisation

makes them subject to the low rate environment as well. It must also be noted that

holding stablecoins entails costs such as foregoing public deposit guarantee schemes

or foreign exchange risk for multi-currency stablecoins. Foreign

currency-denominated bank deposits already offer a substitution possibility for

euro-denominated deposit holders, though they have not been materially exploited as

of now.

36

4.1.2 Impact on monetary policy transmission via banks

A hypothetical significant use of stablecoins as a store of value under the third

scenario could affect the stability and cost of bank deposit funding, which

could pose challenges for bank intermediation capacity. As the financial system

in the euro area is predominantly bank based, changes in the composition and

strength of bank balance sheets can affect the transmission of monetary policy. A

significant use of stablecoins as a “new payment method” under the second scenario

could reduce banks’ fee and commission income and somewhat dent their profitability,

although it would probably not significantly affect their funding conditions. Under the

third scenario, banks may need to shift from deposits to more expensive sources of

funding, thereby potentially increasing the cost of credit for households and smaller,

bank-dependent firms. Further possible implications of stablecoins for SSM banks are

discussed in Section 4.4.

36

A significant substitution towards foreign currency-denominated deposits by the money-holding sector

has not been observed yet, which is consistent with the fact that most customer deposits in the euro area

do not offer a negative interest rate. However, there are indications that, when engaging in international

transactions, some banks prefer to be paid in foreign currency rather than in reserves with the

Eurosystem, in order to avoid the negative deposit facility rate.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

20

4.1.3 Liquidity and money markets

Under the third scenario, stablecoins might affect the demand for central bank

liquidity and thereby the ECB’s steering of euro money market rates. Demand for

central bank liquidity arises, inter alia, from the need to clear payments in central bank

money and to cover liquidity shocks resulting from changes in banknote demand. The

effect of stablecoins on central bank reserve demand would depend on the concrete

design of the stablecoin and the type of collateral used. The substitution of banknotes

and central bank money with stablecoins at a degree envisaged in the second

scenario could reduce the demand for ECB liquidity but would not necessarily

constrain the ability to steer short-term money market rates, as stablecoin reserves

would likely be invested in euro-denominated assets, which would respond to changes

in key policy rates.

The issuance of stablecoins might raise questions about the central bank

acting as a lender of last resort for the institutions that host the stablecoin’s

collateral, as users will expect full convertibility into fiat currency. Even if

stablecoins are collateralised with high-quality assets (such as commercial bank

deposits, money market fund shares and government bonds)

37

– as in, for example,

tokenised funds – a sudden run on stablecoins would require the liquidation of

collateral assets, potentially creating funding strains not only for the stablecoin issuer

and for banks but also for investment funds and other entities that do not have direct

access to central bank lending operations.

4.1.4 Safe asset demand

Under the third scenario, stablecoins collateralised by high-quality liquid

assets (e.g. tokenised funds) might increase the demand for safe assets,

thereby possibly affecting asset price formation, collateral valuation, money

market functioning and monetary policy space. In the event that deposit holders

move from bank deposits to stablecoins, the demand for safe assets could increase

overall if the stablecoin arrangement holds a large share of such assets as part of the

collateral. Safe asset demand may be especially affected if in other jurisdictions

non-euro deposits are substituted for euro-denominated stablecoins on a large scale,

as these inflows would have to be collateralised by high-quality assets denominated in

euro. A higher demand for euro-denominated safe assets might affect the risk-free

yield curve, the exchange rate, asset prices generally and collateral valuation, with

potential implications for rate volatility in repo markets and the pass through of

monetary policy to prices. In addition, an increased demand for safe assets from

stablecoin issuers could also affect monetary policy space by reducing the free-float of

securities available for monetary policy operations (i.e. purchases under quantitative

easing programmes or collateral in credit operations). However, under reasonably

plausible calibration scenarios (i.e. where a limited share of potential users adopt

stablecoins), the impact on risk-free rates of the additional demand for

euro-denominated safe assets is estimated to be limited. Furthermore, an increased

37

By contrast, if a stablecoin issuer had direct access to the central bank’s balance sheet, it would be akin

to a narrow bank and its reserves would be sufficient to redeem any withdrawals.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

21

demand for euro-denominated safe assets could also strengthen the international role

of the euro and bring economic benefits.

38

4.1.5 Exchange rate channel

An extensive use of stablecoins in the second scenario could affect the

exchange rate channel of monetary policy and might make it more difficult for

monetary policy to control domestic developments, as in the case of dollarised

countries. In the case of multi-currency stablecoins, the exchange rate channel might

be affected given that the euro is a global reserve currency and is therefore likely to be

included in stablecoin currency baskets. If a multi-currency stablecoin were to be used

as an invoicing currency, relative prices would be less affected by domestic monetary

policy.

39

At the same time, prices could be affected by foreign monetary policy or

exchange rate shocks. However, the likelihood of multi-currency stablecoins, such as

multi-currency Libra, becoming invoicing currencies is estimated to be low.

Specifically, internal analyses indicate that, under plausible assumptions regarding

Libra’s potential use as an international invoicing currency

40

, the pass through of euro

exchange rate movements to import prices would hardly change. In turn, the

exchange rate pass through would be stronger if invoicing in Libra accounted for a

significantly larger share of euro area imports than assumed above. However, in that

case holdings of Libra per user would rise to much larger – and possibly economically

implausible – levels. At the same time, the euro area economy might become more

exposed to shocks in the value of stablecoins like multi-currency Libra, arising for

example from changes in the value of one of the currencies in the basket. Shocks

affecting the value of stablecoins collateralised by euro would transmit more directly to

the euro area by affecting the purchasing power of the stablecoin holders. In a more

extreme scenario, “digital currency areas”

41

might arise (characterised as a global

network of payments and transactions in a specific stablecoin), which could increase

the international comovement of macroeconomic developments and affect the

cross-border transmission of monetary policy. This might make it more challenging for

monetary policy to stabilise domestic economic developments.

4.1.6 Monetary policy operations

The monetary policy implications outlined above could affect the size of the

Eurosystem’s balance sheet and its structure. This impact would be especially

pronounced under the third scenario where stablecoins are not only used for

payments but also as a store of value. A reduced demand for banknotes and central

38

These benefits include, among others, lower transaction and hedging costs for trading internationally for

euro area household and companies, seigniorage, and being able to issue debt at lower interest rates

(“exorbitant privilege”).

39

Single-currency stablecoins on the other hand should not carry major implications for the exchange-rate

channel.

40

The assumptions are that (i) euro accounts for 30% of the basket of currencies backing Libra (which is

close to the share of the euro in the SDR basket), and (ii) Libra is used as invoicing currency for 5% of

euro area imports – about the combined shares of the renminbi and yen in global payments.

41

See Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

22

bank reserves, which could be the case already in the second scenario, would lead to

a smaller balance sheet and less seigniorage income. If in addition stablecoins were

used as a store of value, this would increase the demand for safe assets as outlined in

Section 4.1.4. In turn, this could lead to scarcity of eligible assets for central bank

policy operations such as asset purchases and open market operations.

42

In addition,

risks arising from traditional counterparties could increase if the use of stablecoins had

financial stability implications for the banking system. If the risk of financial instability

increased beyond the traditional banking sector, the central bank might consider

interacting with a wider range of counterparties. Financial stability issues will be

discussed in the following section.

4.2 Financial stability

Both fragilities within the stablecoin arrangement and the interconnectedness

with the financial systems represent sources of financial stability risks. As the

G7 report on global stablecoins and the FSB consultative document on the regulatory,

supervisory and oversight challenges of global stablecoin arrangements

43

have

already analysed and identified a vast array of financial stability risks from stablecoin

arrangements, the following paragraphs will focus on the two most prominent risks:

risk of a liquidity “run” impairing the functioning of the stablecoin arrangement, and risk

of contagion to the wider financial system emanating from an impaired stablecoin

arrangement.

44

4.2.1 Liquidity run

The value of stablecoins may be exposed to risks inherent in the investment in

non-zero risk financial assets such as credit, liquidity, market and foreign

exchange (FX) risks. An important question from a financial stability perspective is:

who ultimately bears the investment risks? If the stablecoin arrangement does not

guarantee any fixed value of the stablecoin, this will move in tandem with the value of

the “collateral” (see Section 2). In this case, the end user is the bearer of all risks and

the stablecoin is equivalent in substance to a fund share with the price equal to the

fund’s net asset value. There is no solvency risk for such an arrangement as it is akin

to a “pass through” structure.

Runs on the stablecoin arrangement could occur if end users lose confidence

in the issuer or its network. This could happen, for example, if an adverse event

occurs (such as a cyberattack to the system or theft from wallet) or if end users realise

that the collateral assets are losing value, thereby casting doubts on the value of the

stablecoin. Such a realisation could trigger substantial redemptions of stablecoins

which could be amplified to the extent that end users misconceive stablecoin holdings

as a substitute of bank deposits.

42

By contrast, if stablecoins kept the collateral in central bank reserves, this could lead to an expansion of

the balance sheet.

43

See Financial Stability Board (2020).

44

For more detailed discussion, see Adachi et al. (2020).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

23

Runs could also occur when the stablecoin arrangement guarantees a fixed

value of the stablecoin (e.g. some tokenised funds). In this case, any losses

stemming from its investment are borne by the stablecoin issuer (or whoever provides

such guarantees), including losses from exchange rate fluctuations if relevant.

Therefore, confidence in the stablecoin and its arrangement depends critically on the

loss absorption capacity of the guarantor and doubt thereof could trigger a run on the

stablecoin arrangement. (By implication, applicable regulatory requirements have to

be sufficiently comprehensive to addressing complex and interrelated risks posed by

the stablecoin arrangement.)

4.2.2 Contagion effects

In the event of a run on a stablecoin with the scale envisaged in the second and

third scenarios, the liquidation of assets to cover redemptions could have

negative contagion effects on the financial system. It should be noted that shocks

to the stablecoin arrangement in emerging markets with weak institutional capacity

(such as operational incidents) could spill-back to advanced economies in which the

pool of collateral assets mostly reside. Moreover, some components of the stablecoin

arrangement (e.g. designated dealers) may stop their function in a manner similar to

that observed in the 2007 global financial crisis when securitisation vehicles’

redemptions were suspended.

Short-term government debt markets would be most profoundly affected in

such scenarios. As the stablecoin arrangement might represent a significant investor

in the short-term government debt market, runs on it would translate to large price

volatility and illiquidity spikes. In addition, the stability of bank funding may be

weakened as stablecoin holders may have moved funds from bank deposits to global

stablecoins, creating a banking system in which sticky retail deposits are replaced with

institutional deposits as noted in Section 4.1.2.

Banks would be affected through multiple channels in a run: those banks which

have received the arrangement’s collateral could experience a sudden deposit

withdrawal as noted above; those engaged in the arrangement as actors (designated

dealers, third-party trading platforms, etc.) could be subject to associated market

volatility and also with reputational risks for their role.

4.3 Market infrastructures and payments

The core transfer function of a stablecoin arrangement, regardless of the

design of the technical platform (e.g. centralised versus decentralised), can be

characterised as a payment system (see Section 2).

45

Therefore, like other

payment systems, stablecoin arrangements that are not properly managed can be a

source of large-scale disruption and even systemic risk in the second and third

scenarios.

45

Certain stablecoin arrangements may also undertake functions of other financial market infrastructures

(e.g. central securities depositorie s).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

24

Separately from their core transfer function, stablecoin arrangements also

incorporate a function to provide end users with a means of payment similar to

payment schemes. While payment schemes do not give rise to systemic risk

concerns, their orderly functioning facilitates secure and effective payment

instruments that meet users’ needs and are critical for maintaining public trust in the

euro.

4.3.1 Risks posed and borne by stablecoin arrangements in their transfer

function

The multiplicity of functions and entities involved in stablecoin arrangements

raises questions around governance. On the one hand, the involvement of a large

spectrum of stakeholders supports the consideration of diverse market interests and

views. On the other hand, a highly complex governance structure could hamper the

decision-making process pertaining to the arrangement’s design and technological

evolution or by slowing incident responses related to operational issues. Furthermore,

arrangements that rely on intermediaries and third-party providers also bear risks

from, and pose risks to, these entities. Clear and transparent governance is all the

more important for arrangements that operate in multiple jurisdictions and/or currency

areas – as envisaged in global retail stablecoin initiatives.

Stablecoin arrangements that use DLT incur the potential benefits and

drawbacks inherent in any distributed setup in terms of operational reliability

and resilience. Benefits of using multiple synchronised ledgers and multiple

processing nodes include reducing the risk from a single point-of-failure. At the same

time, any arrangement operated by many parties is more prone to cyber risk since it

has a larger attack surface. In this regard, cryptographic tools play a critical role in

ensuring the security and confidentiality of information stored on the distributed ledger.

Furthermore, distributed ledgers are inherently more complex and potentially

resource-intensive to operate compared to traditional systems.

Stablecoin arrangements operating in a cross-jurisdictional context and/or on a

global scale may pose specific risks such as heightened legal risk. Uncertainties

regarding the applicable law and/or the competent court(s) in case of disputes may

result in conflict-of-law issues. This is in addition to the complexities around the legal

and regulatory classification of the asset and the mapping of an arrangement’s

function to the domestic legal and regulatory framework outlined in Section 2 and the

discussion around the legal underpinning of arrangements based on DLT in some

jurisdictions e.g. regarding the ownership or transfer of assets, and settlement finality.

4.3.2 Implications for Eurosystem oversight

Preliminary analysis

46

suggests that the CPMI-IOSCO PFMI provide a sufficient

basis for authorities to assess the systemic importance of stablecoin

46

See Annex 4 of Financial Stability Board (2020).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

25

arrangements, to ensure their safety and efficiency, and to cooperate with other

relevant authorities. While the CPMI-IOSCO has identified no need for an

amendment of the PFMI at this time, the application of PFMI to stablecoin

arrangements may require further guidance regarding the interpretation of current

requirements in the light of the specificities of stablecoin arrangements.

The PFMI provide guidance for relevant authorities to assess the systemic

importance of payment systems which, complemented by the qualitative and

quantitative factors identified by the relevant authorities, could also inform the

assessment of the systemic importance of stablecoin arrangements for the

purpose of PFMI application. The regulation of the ECB on oversight requirements

for SIPS sets quantitative criteria for the assessment of systemic importance.

The entities involved in the transfer function of a stablecoin arrangement could

be subject to the Eurosystem’s oversight. A decision in this respect would consider

the qualification of the asset/activity under EU regulation. For example, if an asset

qualifies as e-money and its issuer is supervised according to EMD2, it is likely that the

respective arrangement qualifies as a payment scheme under the Eurosystem’s

oversight framework. The respective arrangement could still be subject to oversight as

a (proxy to) payment system (provided the criteria outlined in Section 2 were fulfilled)

and/or payment scheme.

As the criteria for the identification of a SIPS are linked to the activity of clearing

and settling euro-denominated payments, the SIPS regulation might not apply

to stablecoin arrangements that handle payments denominated in another

currency or unit of account, yet the system could be subject to the general

payment system oversight framework. In fact, the Eurosystem oversight policy

framework is not limited to systems that clear and settle euro-denominated payments.

The Eurosystem would still be in a position to apply the PFMI, or a subset thereof, to a

non-euro-denominated system that is located in the euro area even though the system

is not subject to the SIPS regulation.

Stablecoin arrangements could also qualify as payment schemes (see

Section 2). The ongoing review of the Eurosystem oversight framework for payment

instruments and schemes should ensure that payment schemes based on stablecoins

that are denominated in, funded by or collateralised by euro, fall under oversight. It is

further noted that, in the event that a stablecoin arrangement qualifies as a payment

scheme, but not as a payment system, the clearing and settlement function of the

arrangement could be regarded as an associated function of the scheme and be

subject to oversight.

Stablecoin arrangements that settle euro-denominated transactions may

warrant the application of the Eurosystem’s location policy. If a stablecoin

arrangement were to reach a certain threshold

47

, it would have to be operationally and

legally located in the euro area under such policy. For other offshore payment systems

47

The location policy requirement applies to all payment systems that either settle more than €5 billion per

day, or account for more than 0.2% of the total daily average value of payment transactions processed by

euro area interbank funds transfer systems which provide for final settlement in central bank money

(whichever of the two amounts is higher).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

26

settling euro-denominated transactions or payment systems with significant

funding/defunding in euro, the Eurosystem would seek cooperative oversight.

48

In

case banks are used to execute economic functions of a stablecoin arrangement, the

already established supervisory arrangements for cross-border coordination will be

employed and amended, if need be, according to the specific arrangement.

Stablecoin arrangements established outside of the EU should be subject to

international cooperative oversight arrangements comprising all relevant

authorities that have a legitimate interest. Responsibility E of the PFMI (together

with the Lamfalussy principles for offshore payment systems

49

) provides a strong

basis for such cooperation, and allows for the involvement of other relevant regulatory

and supervisory authorities if deemed necessary. As an example, the Swiss

authorities created the “Libra College” for the oversight of Libra in which the ECB was

invited to take part. It is, however, noted that the Eurosystem would have no legal

means to enforce such cooperation but would rely on moral suasion (name and

shame).

4.3.3 Implications for the retail payments market

Stablecoins of the types described in the second scenario may alter the current

retail payments landscape in Europe and globally. Both the international payments

landscape – with relatively slow and costly cross-currency transfers – and a

fragmented European retail payments market (e.g. in the front-end of instant payment

solutions at the point of interaction) provide opportunities for stablecoins to meet

users’ demand in terms of speed, affordability, access or convenience. Some

initiatives (e.g. Libra) can leverage existing consumer platforms to maximise user

convenience and expedite take-up (e.g. through incentives). This might affect the level

playing field in payment services and contribute to increasing Europe’s dependence

on global players in the area of payments.

Stablecoin arrangements may also pose concerns for EU market integration

and interoperability. Stablecoin arrangements may fall outside of the scope of SEPA

Regulation that harmonises the way cashless euro payments are made across Europe

and mandates interoperability. While a stablecoin initiative such as Libra may de facto

ensure pan-European coverage, pan-European reachability (intended as all

consumers having the ability to make payments at the national and EU level under the

same conditions) may require a deliberate effort. Furthermore, in the event of multiple

stablecoin arrangements, fragmentation may occur across the arrangements’

networks. From a demand side perspective, users may face trade-offs between

convenience on the one hand and additional costs (e.g. cash-out and other fees, idle

balances) and switching barriers on the other hand.

48

With regard to oversight of cross-border FMIs, Responsibility E of Committee on Payments and Market

Infrastructures and the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (2020) foresees

cooperation with other authorities at international level where appropriate. Cross-border cooperation

among relevant authorities is typically initiated by the authority of the system’s home jurisdiction. The

authority of the home jurisdiction usually has the primary responsibility for the oversight of the system.

49

See Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (1990).

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

27

4.3.4 Implications on the use of euro banknotes for payments

In the second and third scenarios, stablecoins are likely to coexist with ca sh in

payment transactions. This is due to the unique characteristics of cash – being

physical – while stablecoins will primarily compete with other electronic means of

payment at least in a short/medium term. Even in a scenario where stablecoins satisfy

the demand for storing value, they are likely to coexist with euro banknotes. This

applies also to the demand from outside the euro area. There, in fact, euro banknotes

are often held by people who do not trust the currency or banking system in their own

countries, and trust instead an international currency, especially in physical form, i.e.

cash. It is hardly imaginable that in such situations people will store their last resort

assets in a digital form. It is estimated that about 30% of the total euro banknotes

demand originates from outside the euro area.

4.4 Banking supervision and prudential regulation

The possible involvement of supervised institutions in stablecoin

arrangements would both support the materialisation of scenarios in which

stablecoins effectively fulfil a payment and/or store of value function and have

manifold implications for the these institutions. A role for banks in these situations

would reflect on ECB supervision and the adequacy of prudential regulatory treatment

of emerging assets.

4.4.1 Possible roles of SSM banks in stablecoin arrangements

A stablecoin arrangement may rely on banks to ensure its orderly functioning.

50

SSM banks could take up a variety of roles in stablecoin arrangements to facilitate the

creation, redemption, circulation and use of stablecoins. They could fulfil three broad

types of non-mutually exclusive roles in a generic stablecoin arrangement to support

its core functions (stabilisation, transfer, user interaction) also taking into account

jurisdictional restrictions.

1. Provision of various services to the stablecoin arrangement’s stabilisation

function, as e.g. (i) members of the governance body of stablecoin arrangement

who share the responsibility of managing its assets; (ii) custodians of collateral

assets; (iii) asset managers; (iv) prime brokers. In the secondary market, banks

could act as market makers on exchanges, or exchanges per se, thereby helping

to stabilise the price of the stablecoin. They could also support a stablecoin

arrangement’s stabilisation function indirectly by e.g.: (i) receiving deposits from

the stablecoin arrangement, likely to interest-bearing accounts or

50

According to Financial Stability Board (2020), in some jurisdictions stablecoin arrangements already

deposit funds at major banks. This has the potential to: (i) create an additional layer of intermediation

between households and banks; (ii) reduce the stability of bank funding in stress conditions; (iii) impact

the functioning and resilience for the financial markets (e.g. short-term government bonds) in which

reserve funds are invested (see also Sections 4.1 and 4.2). Currently these risks are likely small given the

small scale of existing stablecoin arrangements compared to the balance sheets of major banks.

However, there are limited data to assess such bank exposures.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

28

securities/investments; (ii) selling assets (e.g. short-term government securities)

to the stablecoin arrangement; (iii) providing FX c onversion services; (iv) offering

hedging services, e.g. via derivatives, or market access to such services with

other third parties.

2. Operation of a validating node in the DLT transfer mechanism.

3. Facilitation of the stablecoin arrangement’s interaction with users, as

e.g. providers of custodian wallets and payment services in stablecoins.

Banks’ role in stablecoin arrangements could also go beyond supporting the

core functions, as they could benefit from synergies via the offer of additional

services. For example, banks could take deposits and extend credit in stablecoins,

including via fractional reserve banking. There could be new forms of cross-selling,

such as offering certain financial services or products exclusively to stablecoin users

or at preferential rates. Furthermore, custodian wallets might be linked with other

financial services (e.g. payment account aggregation services) and create a demand

for stablecoin ATMs and merchant acceptance services. Finally, if global stablecoins

fostered greater access, they could trigger demand for additional bank services.

Banks could be subject to a wide range of risks through the provision of such

services, such as governance, liquidity, market, credit, operational and

technological, legal and compliance risks. Governance risk may arise from banks’

lack of understanding of the risks of stablecoins and impaired ability to engage in

effective risk assessment and decision-making and to establish adequate controls.

Banks that receive deposits from stablecoin arrangements could be exposed to

funding risk, whereas banks-resellers are subject to market liquidity risks in situations

of loss of confidence in the stablecoin. Changes in the valuation and pricing of holding

of stablecoins could be a source of risks for banks engaging in trading, dealing, and

market making. Credit risk ranges from intraday exposures to loss of equity in the

event that the project fails. A stablecoin arrangement’s endpoints could be subject to

cyberattacks, leading to e.g. private keys held by banks being stolen. Stablecoin

arrangements may experience operational issues with reputational and legal

implications also for banks. Finally, banks that undertake activities in a stablecoin

arrangement or the broader ecosystem will need to consider the application of

regulatory framework to their businesses.

Providing financial services to a stablecoin arrangement or within the broader

stablecoin ecosystem might not be a profitable strategy for banks in the long

run. Especially on initiatives sponsored by large technology companies, the

proliferation of innovative products and services may not be sustainable if returns do

not outweigh the increased operational complexity and the loss of direct access to

transactional data flows that banks would otherwise accumulate and use to their

business advantage.

Banks may also face increased competition. In the second scenario (“new

payment method”), stablecoins could exert pressure on commissions and fees

charged by banks for payments and transfers. Increased competition may also erode

revenues that banks currently obtain from the payment card business.

ECB Occasional Paper Series No 247 / September 2020

29

4.4.2 Supervisory powers