The ECB’s Future

Monetary Policy

Operational Framework

Corridor or Floor?

Luis Brandao-Marques and Lev Ratnovski

WP/24/56

IMF Working Papers describe research in

progress by the author(s) and are published to

elicit comments and to encourage debate.

The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are

those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board,

or IMF management.

2024

MAR

* The author(s) would like to thank Nassira Abbas, Nazim Belhocine, Ashok Bhatia, Damien Capelle, Oya Celasun, Alfred Kammer,

Malhar Nabar, Vina Nguyen, Jerôme Vandebussche, and Romain Veyrune for useful comments and discussions, Morgan Maneely,

Kayla Qin, and Wei Zhao for excellent research assistance, and Zhuohui Chen for sharing data on money market rates and excess

liquidity.

© 2024 International Monetary Fund WP/24/56

I

MF Working Paper

European Department

T

he ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework: Corridor or Floor?

Prepared by Luis Brandao-Marques and Lev Ratnovski *

Authorized for distribution by Oya Celasun and Malhar Nabar

March 2024

IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit

comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the

author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

AB

STRACT: This paper reviews the trade-offs involved in the choice of the ECB’s monetary policy operational

framework. As long as the ECB’s supply of reserves remains well in excess of the banks’ demand, the ECB will

likely continue to employ a floor system for implementing the target interest rate in money markets. Once the

supply of reserves declines and approaches the steep part of the reserves demand function, the ECB will face

a choice between a corridor system and some variant of a floor system. There are distinct pros and cons

associated with each option. A corridor would be consistent with a smaller ECB balance sheet size, encourage

banks to manage their liquidity buffers more tightly, and facilitate greater activity in the interbank market. But it

would require relatively more frequent market operations to ensure the money markets rate stays close to the

policy rate and could leave the banking system vulnerable to intermittent liquidity shortages that may have

financial stability implications and impair monetary transmission. The floor, on the other hand, would allow for

more precise control of the overnight rate and a lower risk of liquidity shortages, but it would entail a somewhat

larger ECB balance sheet, weaken the incentives for banks to manage their liquidity buffers, and discourage

interbank market activity. The analysis of tradeoffs suggests that, on balance, in steady state, a hybrid system

that combines the features of the “parsimonious floor” (with a minimal volume of reserves) with a lending facility

or frequent short-term full-allotment lending operations priced at or very close to the deposit rate, making it a

“zero (or near-zero) corridor”, would be most conducive for achieving the ECB’s monetary policy objective.

JEL Classification Numbers:

E42, E51, E58

Keywords:

Central bank operations; Monetary policy; The ECB

Author’s E-Mail Address:

WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy

Operational Framework

Corridor or Floor?

Prepared by Luis Brandao-Marques and Lev Ratnovski

1

1

The author(s) would like to thank Nassira Abbas, Nazim Belhocine, Ashok Bhatia, Damien Capelle, Oya Celasun, Alfred Kammer,

Malhar Nabar, Vina Nguyen, Jerôme Vandebussche, and Romain Veyrune for useful comments and discussions, Morgan Maneely,

Kayla Qin, and Wei Zhao for excellent research assistance, and Zhuohui Chen for sharing data on money market rates and excess

liquidity.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

2

Contents

Glossary ............................................................................................................................................................... 3

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 4

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5

2. A Short Primer on Monetary Policy Operational Frameworks .......................................................... 8

3. Benefits and Costs of Corridor and Floor Systems ......................................................................... 12

Monetary Policy ............................................................................................................................................ 13

Interest Rate Volatility and the Risk of Procyclicality and Divergence of Liquidity Conditions .............. 13

Balance Sheet Tools ............................................................................................................................. 16

Monetary Policy Transmission ............................................................................................................... 17

Financial Sector Footprint, Market Discipline, and Financial Stability .......................................................... 21

The Eurosystem’s Finances ......................................................................................................................... 24

4. Path Forward: From the Floor to a Hybrid System .......................................................................... 25

Near-Term Issues ......................................................................................................................................... 25

A Steady-State Framework .......................................................................................................................... 26

5. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................... 32

Annex I. Nonparametric estimation of the demand for bank reserves in the euro area ............................ 33

References ......................................................................................................................................................... 34

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

3

Glossary

APP Asset Purchase Program

DFR Deposit Facility Rate

ECB European Central Bank

ELB Effective Lower Bound

ESTR Euro Short-Term Rate

GFC Global Financial Crisis

LCR Liquidity Coverage Ratio

LTRO Long-Term Lending Operations

MRO Main Refinancing Operations

NFC Nonfinancial Corporations

NSFR Net Stable Funding Ratio

OMO Open Market Operations

OMT Outright Monetary Transactions

PEPP Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program

QE Quantitative Easing

QT Quantitative Tightening

TLTRO Targeted Long-Term Lending Operations

TPI Transmission Protection Instrument

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

4

Executive Summary

Prior to the 2008-09 financial crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) employed a corridor system

for implementing monetary policy, engineering a structural shortage of bank reserves to a level

where the target policy rate cleared the overnight money market. The corridor was followed, until

January 2015, by an intermediate system that was still a corridor but with money market rates close

to its floor. Subsequently, as the ECB lowered the policy interest rate to the effective lower bound

(ELB) and expanded its balance sheet leading to an abundant supply of reserves, it employed a floor

system with the overnight rate bounded from below using the deposit facility priced at the target

interest rate level. At present, with the policy rate well above its ELB and balance sheet

normalization under way, a key question is whether the ECB should return to a corridor system or

maintain some variant of a floor.

This paper compares corridor and floor-based systems to assess which might be most suitable for

the ECB in the short- and medium term. The key difference is that a corridor system comes with a

reduced central bank balance sheet and encourages banks to manage their liquidity more tightly

with greater reliance on interbank markets, whereas a floor system in which the supply of reserves

systematically exceeds banks’ demand enables more robust control over the policy interest rate and

reduces the risk of unanticipated liquidity shortages that may impair the transmission of monetary

policy. A corridor system would become a de facto floor system should excess reserves remain

abundant, and thus is likely incompatible with large excess reserves induced by quantitative easing

(QE), unsterilized use of the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) and Outright Monetary

Transactions (OMT), or large-scale bank liquidity support interventions.

Given the presence of abundant reserves on its balance sheet, the ECB is likely to remain in a floor

system for some time. As it proceeds with quantitative tightening (QT) that shrinks aggregate

reserves, the ECB could transition toward a corridor or a variant of a floor system. Within the floor

systems, the so-called “parsimonious floor” system is characterized by a minimal quantity of excess

reserves that remains consistent with the floor system in principle but comes with the possibility of

money market rates exceeding the deposit facility rate (DFR) if and when there is a liquidity shortage

in the system. To firmly anchor the short-term interest rate at its target, as a precaution, the deposit

facility in a parsimonious floor can be supplemented with a standing lending facility or frequent full-

allotment lending operations priced at or very close to the DFR to provide a ceiling for money market

interest rates, making it a hybrid system that can also be described as a zero (or near-zero) corridor.

Such hybrid system can deliver robust control over the money market interest rate—which would sit

at the DFR most of the time—while reducing the central bank’s balance sheet size. The wider the

corridor, the less the excess supply of reserves should be and the more banks would be encouraged

to manage their liquidity buffers, supporting interbank activity. At the same time, allowing for a wider

corridor in a hybrid system has a higher possibility of intermittent liquidity shortages that may impede

monetary policy transmission. A corridor (or near corridor) system would function more robustly if

coupled with faster progress toward completing the Banking Union that would help ensure such

events do not precipitate wider, systemic banking distress. Learning-by-doing should remain a

guiding principle as the ECB transitions to a steady state operational framework.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

5

1. Introduction

To achieve the ultimate objectives of monetary policy—price and macroeconomic stability

1

—central

banks employ one or more intermediate targets (e.g., an inflation forecast, if the central bank uses

an inflation targeting strategy). To operationalize their intermediate targets, most modern central

banks steer the money market overnight interest rate—the “operational target” of monetary policy

(Bindseil 2014

).

The “operational framework” refers to a set of mechanisms and instruments by which the central

bank supplies reserves to implement a target short-term interest rate. Short-term interest rates are

determined by supply and demand in money markets, where banks borrow and lend central bank

reserves (defined as the balances that banks hold on central bank accounts) to cover their reserve

requirements and liquidity and payments-related needs. Central banks control the aggregate supply

of reserves through the use of monetary policy instruments—they provide and withdraw reserves

through market operations and lending facilities and can “sterilize” reserves through remunerated

deposit facilities, the issuance of central bank securities, or with minimum reserve requirements. By

varying the supply of reserves, central banks steer the equilibrium short-term interest rate.

The choice of a central bank’s operational monetary policy framework matters first and foremost

because it may affect the effectiveness of monetary policy implementation. Although this

effectiveness is ultimately measured by the strength and speed of the transmission of monetary

policy to inflation and output, it is more immediately gauged by the central bank’s ability to influence

short-term money market interest rates and the pass-through of policy-induced movements in the

latter to broader financial conditions. The degree of control over the overnight money market interest

rate—and in the case of a currency union, the uniformity of this control across jurisdictions

(Eisenschmidt et al., 2018

)—as well as the ease with which the central bank can deploy some of its

less conventional tools like quantitative easing (QE) when policy rates are close to the effective

lower bound (ELB) under a given framework are important considerations to assess its

effectiveness. Second, different operational frameworks may imply a different central bank footprint

in financial markets (e.g., some frameworks rest on a well-functioning interbank market to meet

banks’ liquidity needs while others suppress its activity; some may entail more frequent market

operations than others; and some may be associated with a larger central bank balance sheet size

than others), may be more or less robust to financial market turbulence, liquidity shortages, and

bank stress, may increase or reduce the amount of good collateral available to market operators,

and, because they presuppose different sizes and composition for the central bank’s balance sheet,

will have different effects on its profit and loss statement. This means that the choice of the monetary

policy framework will need to consider the pros and cons of each model.

1

Central banks often have other ultimate goals like financial stability, financial development, or an efficient payments system, but

these are not met with monetary policy. In particular for financial stability, whenever and wherever possible, central banks should

follow a separation principle in which monetary policy pursues price stability and prudential policies target financial stability (see

Gopinath, 2023

).

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

6

Some of these considerations for the choice are of an operational framework are of general validity,

while others may be especially important for currency unions, including the euro area. For example,

euro area banks have boosted their liquidity and capital ratios thanks to a wide implementation of

Basel III and have demonstrated their resilience throughout the pandemic shock and during the rapid

tightening of monetary policy in 2022-23. However, long-standing structural differences across

countries in the euro area (e.g., level of public debt and extent of sovereign risk priced in by markets)

as well as the gaps in the financial architecture of the euro area (i.e., the lack of a full banking union

and the consequent heterogeneity of its banks, and, given that the 2021 amendment to the ESM

treaty has not been ratified yet, the still-incomplete bank backstop arrangements) may mean that

liquidity squeezes in the money market—a tail risk scenario—may have disproportionate effects on

the fragmentation of monetary policy transmission in the European monetary union. This

heterogeneity implies a need to ensure stable liquidity conditions for the diverse European financial

sector across the range of possible states of the world, with the purpose of fulfilling the ECB’s

monetary and financial stability objectives.

With these considerations in mind, this paper contrasts options for the ECB’s monetary policy

operational framework—falling in the spectrum of a corridor or a floor.

2

While QT proceeds,

because of abundant reserves, the ECB is likely to remain in a floor system for some time. For the

steady state (i.e., once QT has run its course), based on the analysis of the trade-offs, the paper

argues that the preferred option is a hybrid system that combines the characteristics of a

“parsimonious floor” with a “zero (or near-zero) corridor”.

3

Under this hybrid system, the central bank supplies reserves at the minimum (parsimonious) volume

consistent with the floor system, and banks can deposit their excess reserves if needed in a

remunerated deposit facility, as they currently do. Because banks’ demand for liquidity is uncertain,

there is some possibility that money market interest rates occasionally shift above the deposit facility

rate. To avert excessive fluctuations in the money market rate, the hybrid system complements the

deposit facility with a standing lending facility or frequent fixed-rate full-allotment lending operations

2

Before the global financial crisis (GFCC), the ECB employed a corridor system for implementing monetary policy, which

engineered a structural shortage of bank reserves to a level where the target policy rate cleared the overnight money market by

equilibrating the supply and demand for bank reserves. The corridor system lasted until the GFC and was followed by an

intermediate system until January 2015, in which there was a corridor, but money market rates were close to a floor given by the

ECB’s deposit facility rate (DFR). After that, the ECB has implemented a floor system in which an abundant level of excess reserves

has set money market rates very close to the floor.

3

A parsimonious floor is a floor framework with the smallest central bank balance sheet size—or structural liquidity surplus—

required to operate it (Della Valle, King, and Veyrune, 2022

), with both structural and fine-tuning operations required to offset

autonomous factors and short-term fluctuations on the demand for liquidity (Mæhle and King, 2022). In a zero corridor, the central

bank implements, through a standing lending facility, a price ceiling on reserves and could be implemented with any level of

aggregate reserves as long as there is a deposit facility priced at the same rate as the lending facility.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

7

priced at or slightly above the deposit facility rate, capping the money market interest rate from

above and thereby making the framework a zero-width or near-zero-width corridor.

4

Compared to the current floor system with abundant reserves and thus liquidity, a near-zero corridor

would come with significantly less ample reserves and require banks to strengthen their liquidity

management, improve their forecasts of reserve demand over the maintenance period, and rely

more on the interbank market for meeting liquidity needs. This set up also opens the possibility of

intermittent liquidity shortages and the prospect of self-fulfilling liquidity runs—which would call for

faster progress toward completing the banking union for the euro area countries to ensure such

events do not precipitate wider, systemic banking distress. A zero corridor would better stabilize

liquidity conditions but weaken banks’ incentives for liquidity management relative to a near-zero

corridor and leave a smaller role for interbank markets. Having said that, the choice of operational

framework should not be seen as policy tool that seeks to engender changes in bank behavior.

Rather, appropriate liquidity management, risk management, and overall resilience of banks should

be ensured by intensive supervision, adequate financial regulation, and structural measures to

enhance resiliency such as the completion of the Banking Union and a stronger crisis management

and deposit insurance system.

A hybrid parsimonious floor / zero or near-zero corridor system would allow the ECB to control the

overnight money market rate more precisely (relative to a standard corridor system) and would be

consistent with a total amount of euro area bank excess reserves of about 1.3 trillion euros or less,

based on our estimates, compared with 3.5 trillion as of February 2024. Moreover, compared to a

standard corridor system, it would also be more compatible with the use of balance sheet tools if

policy rates were to near the effective lower bound (ELB) again. Finally, it would be more compatible

with the activation of the ECB’s anti-fragmentation tools like the Transmission Protection Instrument

(TPI).

The rest of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 gives a brief overview of different types of

operational frameworks. Section 3 discusses economic trade-offs that characterize the choice

between corridor and floor systems. Section 4 explains why the ECB would likely need to maintain

the current floor system until the size of the balance sheet is reduced further via QT and outlines the

considerations for a potential transition to a hybrid parsimonious floor / zero or near-zero corridor

system in a future steady state. Section 5 concludes.

4

This would also bring the ECB’s operational framework close to what is being envisaged by other large advanced-economy central

banks like the United States Federal Reserve System and the Bank of England, who also have to deal with large and sophisticated

financial systems.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

8

2. A Short Primer on Monetary Policy

Operational Frameworks

The operational framework of most central banks includes the modalities for open market operations

(OMO; the purchase or sale of securities), standing facilities (lending or deposit), other types of

central bank lending to banks, asset purchase programs, and minimum reserve requirements. The

precise definition and use of these instruments varies by central bank.

5

Different frameworks rely on

all or only some of these instruments to achieve a level of central bank liquidity consistent with a

target level for a short-term interest rate and an admissible volatility around said target. Regarding

the permissible level of interest rate variation, monetary policy operational frameworks come in three

flavors: a ceiling, a corridor, and a floor.

In a ceiling system, central banks abstain from providing liquidity to the banking system through

open market operations thereby ensuring that the system has a structural liquidity deficit. This deficit

means that banks will systematically be short of central bank reserves to meet reserve requirements

and their needs for reserves for liquidity and payments purposes. Such a deficit will be met by using

the central bank lending or discount facilities priced at the policy interest rate. Since banks will need

to borrow from the central bank at the policy rate and will never choose to borrow from other banks

at a higher rate (absent stigma),

6

the overnight interbank market rate will be equal to the central

bank’s discount rate, which will therefore be an anchor for short-term interest rates. This operational

framework was common before World War I (Bindseil and Jablecki, 2011

).

In a corridor system, which was deployed by most advanced economy central banks before the

Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central banks engineer a structural shortage of bank reserves to a

level where the target short-term interest rate clears the money market by equilibrating the supply

and demand for bank reserves.

7

To ensure that the money market interest rate hits its target, central

banks must correctly anticipate aggregate demand for reserves as a function of the interest rate. A

common mechanism, also used by the ECB pre-global financial crisis (GFC), involves setting target

reserves based on demand schedules formulated by banks themselves ahead of each policy

meeting, fulfilling this declared liquidity demand, and, in order to ensure that banks have incentives

to forecast their liquidity demand correctly, penalizing banks whose average reserves over the

5

A description of the ECB’s instruments can be found here: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/html/index.en.html.

6

Stigma in the context of monetary policy operational frameworks refers to the reluctance that banks may have in borrowing from

the central bank’s standing lending or discount facility. In the case of stigma, banks prefer to borrow from the money market at a

higher rate for fear of it signaling to markets that they exhausted their ability to borrow in the money market. See

Armentier and

others (2015) for an historical perspective of stigma associated with the United States Federal Reserve’s discount window.

7

Reserves are scarce in a corridor system in the sense that the central bank tightly controls the amount of reserves held by banks

so that there is an opportunity cost for the latter to hold excess reserves (Borio, 2024

) or too little reserves.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

9

maintenance period (from one policy meeting to the next) deviate from the target in either direction.

8

Notwithstanding this mechanism, aggregate shocks in the demand for reserves during the

maintenance period may cause the interest rate to deviate from its target. In this case, a central

bank can adjust the supply of reserves with “fine-tuning” open market operations and/or use

standing deposit and lending facilities priced at a margin around the target interest rate to provide

upper and lower bounds for the money market rate (thus, the ‘corridor’ framework). Traditionally, the

width of the corridor was +/- 100bps around the policy rate in major central banks, including for the

ECB between 1999 and 2013, although some central banks employed narrower +/- 25bps corridors.

In a floor framework, which has been the norm for large, advanced economies since the GFC,

central banks supply reserves in abundance through OMO, lending to banks, or asset purchase

programs, and provide a floor for the price of reserves (interest rate) through a deposit facility. For

example, the current ECB framework involves the supply of abundant reserves, in excess of reserve

requirements and reasonable additional banks’ reserves demand for liquidity and payments

purposes. Then, the laissez-faire price of reserves (interest rate) could be very low, but the ECB

bounds it from below using the deposit facility priced at the target interest rate level (Figure

1 summarizes the interest rate implementation mechanisms in the corridor and the floor

frameworks). The expansion of bank reserves held at the ECB that took place between 2008 and

2022 was primarily driven by large scale asset purchases and targeted longer-term refinancing

operations (TLTROs) and, during periods of acute market distress, refinancing operations and

emergency asset purchase programs like the pandemic emergency longer-term refinancing

operations (PELTROs) and the pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP), respectively. Most

of these programs are being wound down, which will lead to a smaller ECB balance sheet. Still, for

the maintenance of a floor system, the ECB and other central banks will likely need to maintain a

nontrivial amount of aggregate reserves backed by a structural bond portfolio (maintained through

OMO) and/or structural longer-term refinancing operations (Lane, 2023c

).

8

In the context of the ECB’s operational framework, the main penalty for banks failing to adequately forecast their liquidity needs to

meet reserve requirements comes from having to borrow and the marginal lending facility rate (LFR), which is 100 bps above the

DFR and 50 bps above the main refinancing operations (MRO) rate. The other penalty comes from not meeting reserve

requirements, in which case a 250bps penalty applies. The purpose of averaging over the maintenance period is that requiring more

stringent, daily compliance with target reserves would make money markets illiquid, as banks would be unwilling to lend or borrow

reserves in response to high-frequency idiosyncratic demand shocks. Note that reserve targets, as a tool for forecasting the banks’

demand for reserves, are distinct from reserve requirements that are used for liquidity management (sterilization) and financial

stability purposes.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

10

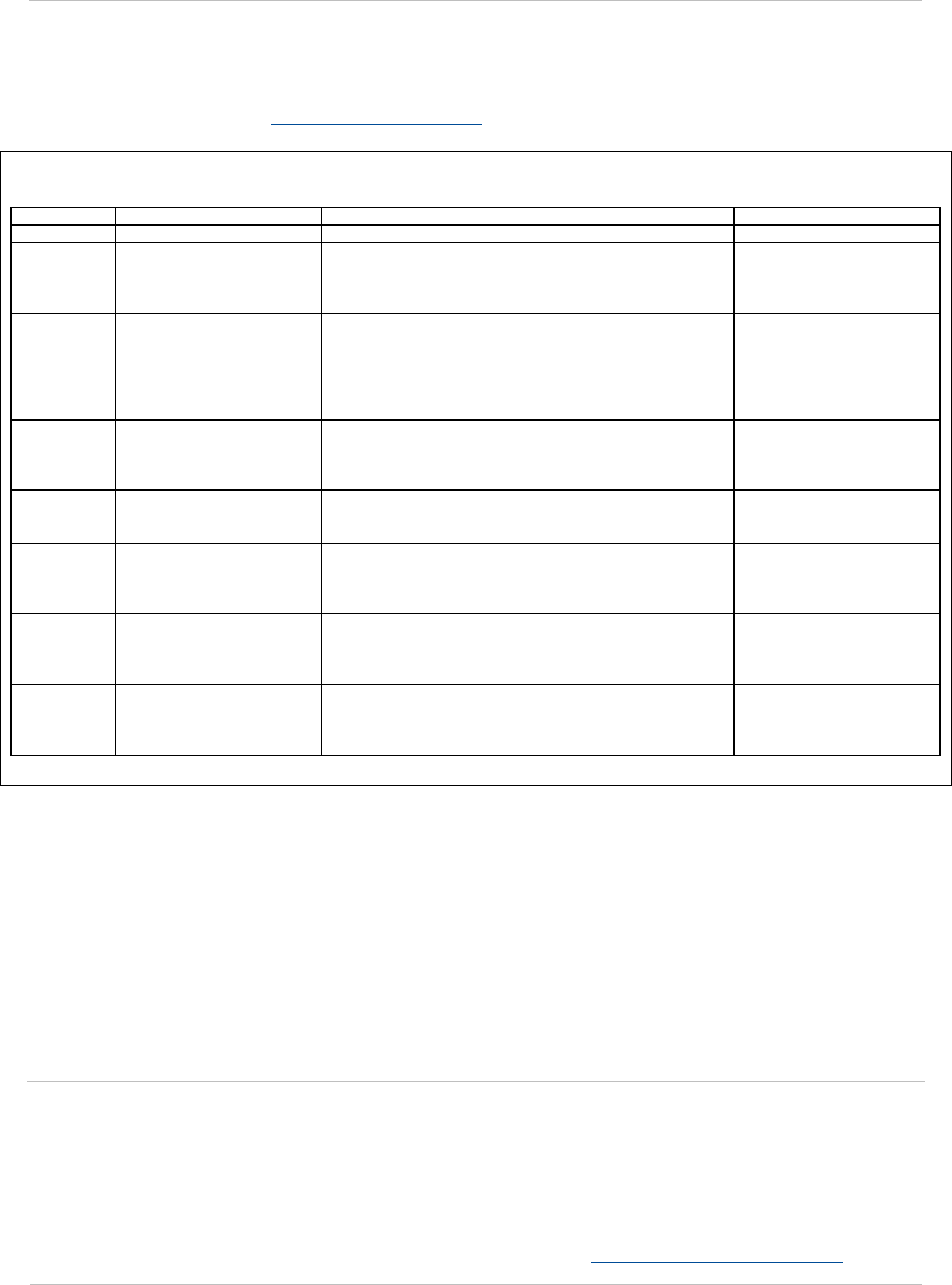

Figure 1. ECB Corridor and Floor Frameworks

A variant of a floor framework is a “parsimonious floor”, which is a floor system with a minimal supply

of reserves that is just sufficient for the system to function as a floor system. This places the supply

of reserves close to, but somewhat above, the level at which the money market rate starts being

sensitive to the supply of reserves—the steep part of the reserves demand curve. However, the

demand curve for reserves is difficult to estimate with precision, so the money market rate in a

parsimonious floor may be unstable: bounded from below by the deposit facility rate but occasionally

rising above. Hence, to ensure that the interest rate robustly remains at the deposit facility level even

if the demand for reserves proves to be higher than anticipated, the central bank can supplement the

parsimonious floor framework with a standing lending facility or frequent full-allotment lending

operations priced at or slightly above the deposit rate, resulting in a hybrid system that also has the

characteristics of a zero or near-zero corridor,

respectively.

Unlike in a standard corridor system, in the near-zero corridor, the central bank does not strictly

target the mid-point of the corridor, but rather permits the money market rate to fluctuate between

the deposit and lending facility rates depending on banks’ liquidity demand. While targeting an

interest rate range instead of a point implies less precise monetary policy implementation, when the

spread between the deposit and lending facility rates is small enough (for example, 25 bps), interest

rate volatility within this narrow range may be relatively inconsequential for financial conditions and

macroeconomic outcomes. Moreover, given that the level of excess reserves will be close to where

the demand for reserves become sensitive to the money market rate, this rate will be at the deposit

facility rate most of the time.

Thus, in what follows, when this paper speaks of a corridor system, that

implies a standard corridor system (akin to what the ECB had in place prior to the GFC), whereas

zero and near-zero corridors correspond to the implementation of the hybrid system that combines a

O/N interest rate

CB reserves

LF rate

MRO rate

DF rate

Supply of reserves

in a Corridor system

Minimum supply of

reserves in a Floor system

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

11

parsimonious floor with a standing lending facility and fixed-rate full allotment lending operations.

Figure 2 summarizes the types of operational frameworks discussed so far.

Figure 2. Types of Operational Frameworks for Monetary Policy

Different operational frameworks are consistent with various levels of central bank excess reserves

provided to the banking system (Figure 3). The corridor system relies on providing the volume of

reserves matching the bank’s demand for reserves. The floor system is implemented using abundant

reserves. As the volume of reserves in the floor system declines, the floor system risks becoming

unstable in case the supply of reserves suddenly becomes binding, inducing the money market rate

to de-anchor from the deposit facility rate. The hybrid system based on zero or near-zero corridor

can, in principle, be implemented with any level of excess reserves – but using the volume of excess

reserves corresponding to the parsimonious floor allows using the minimal volume of reserves

consistent with a policy rate anchored to the deposit facility rate, a framework which

Afonso and

others (2023b) call ample reserves.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

12

Figure 3. Consistency of Excess Reserves with Operational Framework

Note: Green = feasible combinations. Red = infeasible combinations. Orange = an unstable combination.

3. Benefits and Costs of Corridor and Floor

Systems

Conceptually, the choice of the operational framework is driven by the central bank’s preferences

regarding overnight interest rate volatility around the policy rate target, the effectiveness of monetary

policy transmission, the size of the balance sheet, the size and frequency of open market operations,

the scope to implement financial stability interventions, and, in the case of the ECB, the need to

preserve unified transmission of monetary policy across different jurisdictions (i.e., to mitigate

fragmentation risks that would impair monetary transmission). All else equal, central banks prefer

low policy rate volatility, small and infrequent open market operations, and a small balance sheet—

the latter reflecting both political economy considerations (Afonso and others, 2023b

) and a

preference to avoid a potentially distortionary footprint in financial markets.

These multiple central bank objectives involve trade-offs. For example, achieving lower policy rate

volatility may require frequent and sizeable open market operations in a corridor framework or a

large balance sheet that underlies a floor framework. Therefore, the choice of an operational

framework would depend on the balance and the relative hierarchy of these objectives.

In what follows, we review the benefits and costs of the corridor and floor operating frameworks as

they relate to monetary policy implementation and effectiveness, financial stability, and central bank

finances.

No excess

reserves

Ample excess

reserves (small

positive amount of

excess reserves)

Abundant excess

reserves

Corridor

Floor

Zero or near-zero corridor,

including the hybrid

parsimoiuous floor

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

13

Monetary Policy

Interest Rate Volatility and the Risk of Procyclicality and Divergence of Liquidity Conditions

In a corridor framework, the money market interest rate can fluctuate around its target, possibly

substantially so in stressed periods. While such interest volatility encourages banks to manage their

liquidity buffers more carefully, it may also make monetary policy implementation less precise.

9

Indeed, the implementation of a corridor framework, in which a central bank provides a quantity of

reserves to hit a target price of reserves (interest rate), hinges on the accurate anticipation of the

aggregate demand schedule for reserves (volume of demand as a function of the interest rate) by

banks and the central bank alike. But the demand for reserves is volatile and hard to predict with

high precision. Consequently, in corridor systems, the money market interest rate tends to fluctuate

around its target, up to the bounds determined by the central bank’s lending and deposit facilities –

usually mildly so in normal times, but with potentially large deviations from the target rate during

periods of stress. Figure 4, where the pure corridor system covers the period up to and including

2008, suggests that the corridor bounds were rarely approached before the GFC. However, in the

aftermath of the GFC, rates approached the floor of the system as the ECB increased liquidity

provision to banks through long-term lending operations (LTRO) with expanded collateral eligibility

(Constancio, 2018; Hartmann and Smets, 2018

) and remained volatile during the euro area

sovereign debt crisis.

Figure 4. Volatility of Money Market Interest Rates

By contrast, in a floor framework with excess reserves, the central bank guides short-term interest

rates by a price rather than a quantity mechanism, and target money market interest rates can be

implemented more precisely during all market conditions. Indeed, Figure 4 shows a marked decline

in the volatility of the money market interest rate once the ECB shifted to the floor system in 2015. In

9

Potter (2016) argues that, with a corridor system, interest rate volatility in the interbank market is for the most part an artifact of

reserve requirements and induced by the central bank.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

14

fact, the floor system regime implemented after January 2015 had the lowest money market interest

rate volatility since the inception of the Eurosystem.

10

The volatility of the money market rate around its target has several implications. First, when the

central bank is less able to hit the target interest rate, it may be more difficult to implement a desired

monetary policy stance in a highly precise manner. Conceptually, this imperfection can be mitigated

in systems with a narrower corridor.

11

But a corollary is that relative to a wide corridor, a narrow

corridor system with no excess reserves may require the central bank to engage in more frequent

fine-tuning open market operations. Moreover, banks may use the lending and deposit facilities more

actively and trade less actively in the interbank market, implying a de-facto larger central bank

presence in financial markets. These effects may be particularly pronounced for the ECB, as

Europe’s financial system is more diverse and complex than that of the jurisdictions that have used a

narrower corridor, which could make the forecasting of the demand for reserves more difficult.

12

Second, the volatility in money market rates could be procyclical. In anticipating their funding

conditions, banks must account not only for the target interest rate, but also for the risks and risk

premia associated with the fluctuation of the money market interest rate around its target. High risk

premia imply de facto tighter funding conditions than those implied by the target interest rate alone.

In stressed times, the precision with which a central bank can hit the target interest rate is lower, and

thus money market risk premia are higher – implying a de-facto pro-cyclical tightening of money

markets, up to the level implied by the corridor’s upper bound. Additionally, as the deviations of

money market rates from the target are a visible indication of money market stress, they may induce

further, self-fulfilling money market tightening (e.g., Hughes, 2023,

describes a recent self-fulfilling

money market tightening episode in the United States). While in principle a central bank could offset

such tightening by loosening the monetary policy stance or providing additional liquidity (reserves) to

the banking system, the response time of such interventions may leave the financial system exposed

to at least temporary and potentially self-fulfilling liquidity tightening episodes in practice.

Finally, while higher borrowing rates for weaker banks in a corridor framework may encourage them

to improve their liquidity management, and ultimately their fundamentals, these banks could face

stigma that could unduly amplify their financial stress. In the euro area context, this may also imply a

divergence of liquidity conditions across countries, as had occurred in the euro area during the GFC

and the European sovereign debt crisis (see Garcia-De-Andoain and others, 2014

). When banks

10

The ECB has had three regimes for the operational framework so far. The corridor system lasted until the GFC and was followed

by an intermediate system until January 2015, in which there was a corridor, but money market rates were close to the floor. After

that, the ECB has implemented a floor system. The estimated time-varying volatilities of the first difference of the EONIA/ESTR rate,

according to a GARCH(1,1) process for each regime, are 0.0633, 0.0451, and 0.0067 for the corridor, intermediate, and floor

regimes, respectively, and are all statistically different from each other at the 1 percent level.

11

For example, pre-Covid, the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Bank of Canada, and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand used a +/- 25

bps width corridor.

12

Furthermore, as the corridor narrows, it becomes increasingly akin to a zero-corridor implementation of the parsimonious floor

system (Section 4). In these circumstances, a parsimonious floor might be preferrable, as it would have broadly similar properties

but reduce the risk of a lending facility stigma.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

15

avoid using the central banks’ lending facility, a formally symmetric corridor may become de facto

asymmetric (Lee, 2016

). Then, the effective implementation of the interest rates would require the

central bank to have information not only on the aggregate but also on bank-specific demand for

reserves, a high informational bar (

Bindseil, 2014). The corridor framework therefore requires that

the supervisors closely monitor banks’ financial conditions and liquidity management practices and

induce corrective action where necessary.

Still, unlike for the U.S. Federal Reserve’s discount window, the evidence of stigma when it comes to

euro area banks accessing the marginal lending facility is somewhat inconclusive. On the one hand,

euro money market rates have never surpassed the ECB’s marginal lending facility rate (i.e., euro

area banks have never chosen to avoid borrowing from the ECB and borrow instead from the

interbank market at a higher rate). Although the reasons for a lack of stigma are not totally clear, the

way the ECB communicates about its marginal lending facility (as being just another overnight

facility that banks can tap into instead of only a lender of last resort facility) may have played a role

(Lee and Sarkar, 2018

). On the other hand, there is evidence of stigma in the access to ECB dollar

swap lines by euro area banks—made clear by widening deviations from the covered interest

parity—during the 2010-2012 European debt crisis which lessened their effectiveness in dealing with

stress in the dollar funding market (

Allen and Moessner, 2012).

The volatility of the money market rate also relates in part to the uncertainty surrounding banks’

demand for reserves. Aggregate demand for reserves may be more uncertain at present than in the

past, and data from the pre-GFC corridor framework period may not reflect well the regularities that

apply today (Aberg and others, 2021; Schnabel, 2023

). A key reason is that the regulatory changes

enacted since the GFC now require banks to hold substantial amounts of high-quality liquid assets

(HQLA) to manage liquidity risk. Being subject to liquidity requirements and, more generally, having

more rigorous liquidity risk management has made banks more resilient to liquidity runs compared to

pre-GFC and GFC periods, but has likely substantially increased their demand for reserves and

made it more difficult to predict (

Aberg and others, 2021). Relatedly, in assessing the demand for

reserves, banks and the ECB must consider the effects of financial innovation, including the larger

role of nonbanks in the financial system and their liquidity and payments needs, the effects of a more

digital and effective payments system, and the potential implications for the demand for reserves of

the introduction of the CBDC.

13

These changes may have made liquidity forecasting potentially less

certain and more costly in terms of central bank analytical resources (Box 1).

13

Note that, depending on the design of the CBDC, its introduction will likely affect the demand for reserves in a regime of scarce

reserves, but not necessarily in a regime of abundant reserves. When a household transfers funds from a bank deposit account to a

CBDC account, as it would happen with a request for cash, bank reserves are destroyed (either by a reduction in vault cash or a

drawdown of the commercial banks’ deposits with the central bank). Under scarce reserves, the central bank will likely need to

create additional reserves to satisfy the household’s demand and the commercial bank’s demand for liquidity. By contrast, when the

same happens in a regime of ample reserves, a commercial bank can settle this transaction by transferring own excess reserves to

the central bank to credit against the household’s CBDC account, without requiring the central bank to issue more reserves.

Moreover, Abad and others (2024)

show that depending on the take-up of the CBDC, a central bank could follow a floor (low take-

up), or need to follow a corridor (medium take-up) or a ceiling (high take-up) operational framework.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

16

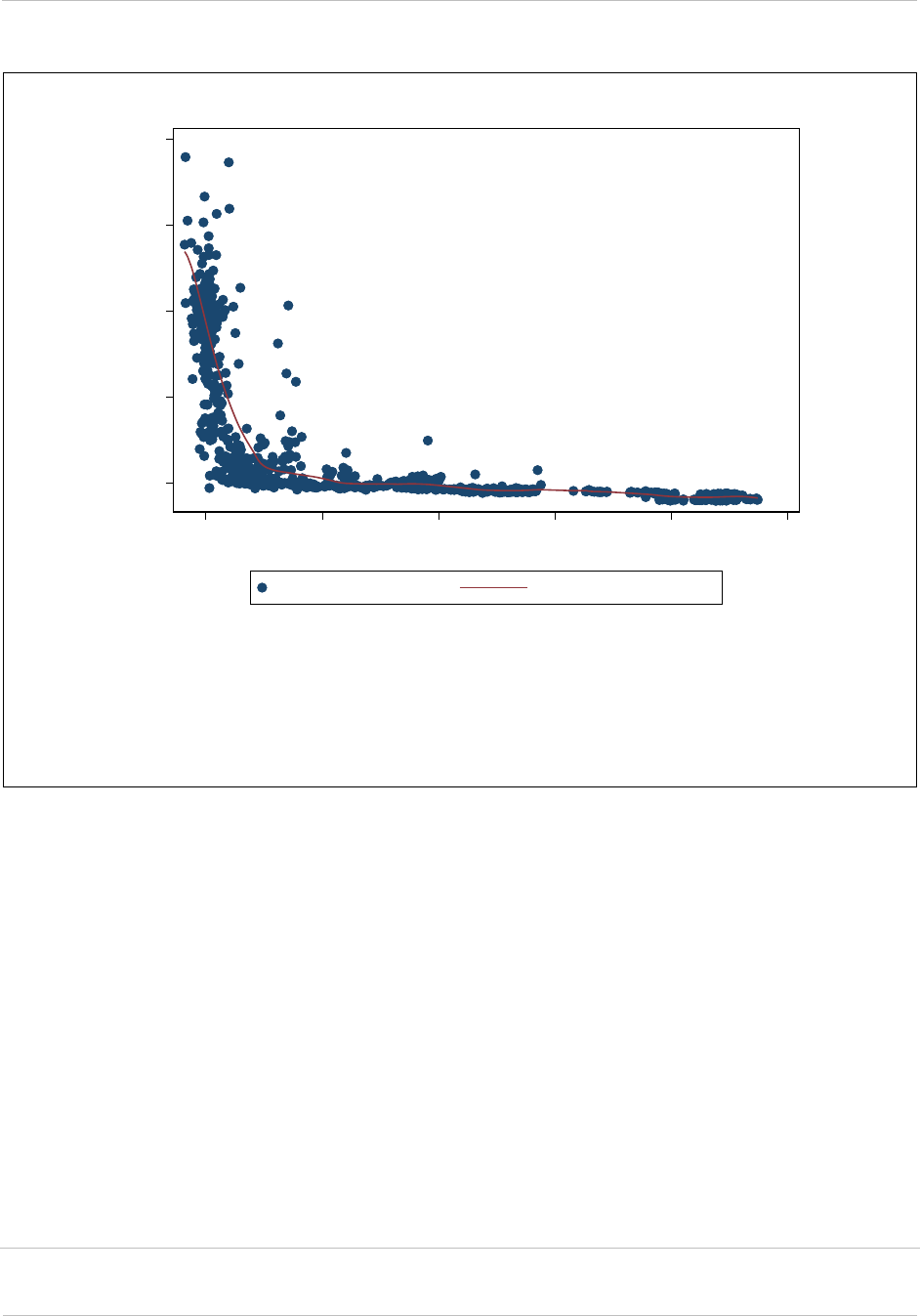

Box 1. Factors Affecting the Demand for Reserves

The state-of-the-art knowledge on the demand for reserves is that the demand curve is nonlinear and

unstable (see Afonso and others, 2023a, for evidence for the United States and a conceptual framework). The

nonlinearity comes from a kinked demand curve around the satiation level of reserves. The instability comes

from horizontal and vertical shifts to demand.

Horizontal shifts to the demand are driven by factors

that shift the demand for reserves at every price

(interest rate) level. These include changes in bank

liquidity regulation (e.g., the LCR requirements) and

structural changes in money market liquidity (e.g.,

liquidity hoarding by banks as the perceived risk

sharing benefits of interbank market activity

decreases). Horizontal shifts in bank reserves can shift

threshold points for the transition between the

regimes of abundant reserves (where the demand curve is flat), ample reserves (where the demand curve is

gently downward sloping), or scarce reserves, making exact thresholds uncertain. While these factors may be

slow moving, they may complicate the transitions from the floor to the corridor framework.

Vertical shifts in the demand for reserves reflect factors that affect banks’ ability to arbitrage the differences

between policy interest rates (e.g., the DFR for the ECB) and interbank or money market rates (e.g., the Euro

Short-Term Rate (ESTR) for the euro area). These factors include changes to banks’ balance sheet costs

which constrain their balance sheet space (i.e., the ability to expand their balance sheets), including those

caused by regulations like limits to the leverage ratio (a lower cap on the leverage ratio would shift down the

demand for reserves). The practical implication of these vertical shifts is that spreads between policy rates

and overnight money market rates may be imprecise or inconsistent over time indicators of the ampleness

of reserves.

Balance Sheet Tools

In a floor system, the size of the balance sheet and the overnight interest rate are disconnected

(Reichlin and others 2021

). In a corridor system, however, the short-term interest rate responds to

changes in the size of the central bank’s balance sheet. Thus, a corridor framework is likely

inconsistent with the use of central bank balance sheet tools to ease financial conditions, because

tapping these tools leads to a sizable increase in reserves, effectively lowering the money market

rate to the floor. Since the GFC, central banks have used balance sheet tools to overcome the zero

lower bound, support financial stability, and mitigate the risk of divergent responses to monetary

policy across the euro area. Since the GFC, the ECB implemented QE through instruments such as

APP, LTRO/TLTRO, and PEPP,

14

which are now being rolled back as part of QT. Also, the ECB has

created important contingency instruments—TPI and OMT—to limit the risk of fragmentation of

financial conditions in the euro area. Consequently, should the ECB shift to a corridor system, any

future use of balance sheet tools would likely require a de-facto shift back to a floor system.

14

Full PEPP principal reinvestment is expected to continue until mid-2024, after which the ECB plans to reduce this portfolio by 7.5

billion euros per month, on average (ECB 2023

).

i

Ample

reserves

Scarce

reserves

Abundant

reserves

Reserves

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

17

The potential complexity and signaling costs of the repeated transition to a floor framework,

15

ceteris

paribus, could make the ECB’s use of contingency tools—TPI/OMT—less credible in the eyes of the

market participants, potentially compromising the stability of the euro area financial markets in times

of stress. Theoretically, the additional reserves created by TPI/OMT operations could be sterilized if

the ECB simultaneously sold sovereign bonds of counties not affected by financial fragmentation.

However, as such sterilization would likely require selling bonds of countries that are not targeted by

TPI/OMT, it may: risk unintended market impact due to the market’s potentially limited absorption

capacity especially as the activation of TPI/OMF would likely occur during stressed conditions; be

operationally complex (as relates to dealing with the absorption capacity risks and the potential

capital key constraints), and potentially be politically charged given that the sale of assets involved in

the sterilization would create explicit “winners and losers” from TPI/OMT as relates to sovereign debt

markets. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that hinging the use of TPI/OMT on a simultaneous

sterilization of the created reserves may negatively impact the credibility of the future use of these

instruments.

Monetary Policy Transmission

From a conceptual perspective, the effects of the corridor and floor frameworks on monetary policy

transmission are mixed (Table 1). On the one hand, because the floor system (or its variations, the

zero- or near-zero corridor systems) can implement target interest rates more precisely at any point

in time, the longer-term interest rates will more precisely reflect the expected path of the target short-

term rates, possibly achieving better pass-through of policy interest rates along the yield curve under

the expectations hypothesis of the term structure of interest rates. Similarly, as the floor system is

more consistent with the potential for future QE, central banks can better control long-term rates

near the effective lower bound and ensure more consistent monetary policy transmission across the

euro area (by providing abundant liquidity, if needed, to all banks in the system), thanks to either

actual QE or central bank communication about potential QE. Relatedly, the floor framework, by

allowing the use of central bank balance sheet tools such as TLTRO, allows a more direct impact on

bank liquidity conditions and incentives to lend, which may strengthen monetary policy transmission

over the business cycle.

On the other hand, the corridor framework avoids conditions where banks have access to de-facto

unlimited liquidity in the form of central bank reserves, and some literature suggests that bank

deposits and lending may respond to policy interest rates more forcefully when banks are less liquid

(Kashyap and Stein, 2000).

16

However, more recent studies suggest that the transmission of

monetary policy to interbank and lending rates, as well as to lending volumes, may be stronger

under a floor system with abundant reserves than under a corridor system with a lean balance sheet

15

However, there remains disagreement concerning how cumbersome it would be to revert to a floor system from a corridor every

time the central bank needs to deploy unconventional monetary policy with Borio (2023, 2024), for example, arguing it would not be

very much so.

16

The reason is that monetary policy transmits to banks also through funding liquidity conditions, and changes in funding liquidity

affect the lending capacity of less liquid banks more.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

18

if interbank markets are not very efficient and interbank rates include a significant liquidity premium

when reserves are scarce (Bianchi and Bigio, 2022).

17

Table 1. Conceptual Considerations on Transmission in Floor vs. Corridor

Recent analysis in Breyer and others (2024) shows that bank liquidity mattered in the euro area for

transmission of policy rates to bank deposit rates but not to the loan rates during the ECB’s 2022-23

tightening cycle (Box 2). While there is evidence that the transmission of policy interest rates to bank

deposit rates (i.e., pass-through) is weaker when banks’ liquidity positions—as captured by LCR and

NSFR—are stronger, excess reserves by themselves (a characteristic of a floor system) do not

correlate with pass-through to deposit rates based on cross country data for all euro area countries

in 2022. The latter finding might reflect the fact that reserves are but one component of overall bank

liquid asset holdings.

18

Importantly, and more directly related to the transmission of monetary policy

17

The argument relies on the interaction between liquidity and capital requirements, and the existence of frictions in interbank

markets. Such frictions generate a liquidity premium when reserves are scarce, but not when they are past the point in which banks’

reserves are no longer sensitive to the interest rate. Increasing the deposit facility rate when reserves are scarce can lead to an

expansion in deposit creation (now cheaper) and lending, and an incomplete pass-through to interest rates (because the liquidity

premium is shrinking). However, when reserves are abundant, interest rates move one-to-one with the deposit facility rate (strong

pass-through) and, because capital requirements will always bind with abundant reserves, lending will unambiguously fall.

18

Moreover, low transmission of policy rates to deposit rates may imply stronger monetary policy transmission to bank lending as it

may, ceteris paribus, reduce the volume of bank deposits and hence bank lending (Drechsler, Savov, and Schnabl, 2017

).

Floor with abundant reserves Corridor

Zero-corridor Near-zero corridor

Footprint in

money markets

Large with very limited interbank

market activity.

Large with very limited interbank

market activity.

Large with limited interbank market

activity.

Limited, depending on width of

corridor. With a narrow corridor,

footprint increases with frequency

and size of OMO.

Footprint in

(other) financial

markets

Large given large central bank bond

holdings. Large excess reserves.

Medium with moderate sized

excess reserves and/or direct

lending to banks.

Medium with moderate sized

excess reserves and/or direct

lending to banks.

Limited, in normal times. With

increased money market volatility,

central bank lending to banks may

increase. Reliance on interbank

market may add financial fragility

and make LOLR more frequent.

Volatility of policy

rate

Zero with possibly better

transmission along yield curve.

Zero with possibly better

transmission along yield curve.

Zero or limited, with possibly better

transmission along yield curve.

Could be high, which adds to lending

rates through higher liquidity

premium (but not clear how big an

issue in normal times).

Transmission to

deposit rates

Low for overnight and demand

deposits, some transmission to

longer term deposits.

Possibly higher than under floor

with abundante reserves but lower

than under a corridor.

Possibly higher than under floor

with abundante reserves but lower

than under a corridor.

Higher than under any floor system.

Transmission to

lending rates

Strong transmission to interbank and

bank loan rates.

Strong transmission to interbank and

bank loan rates.

Strong transmission to interbank and

bank loan rates.

Somewhat weaker transmission if

interbank market is not very

efficient and liquidty premium is

high.

Transmission to

bank credit

Strong, especially if capital

requirements are strict.

Strong, especially if capital

requirements are strict.

Strong, especially if capital

requirements are strict.

Weaker than under floor and

possibly in the wrong direction if

capital requirements are lax and

reserves low.

P&L cycle

Amplified, with strong earnings in

easing phase and high losses in

tightening phase.

Variable depending on how far is the

aggregate supply of reserves to the

right of the point of satiation of

demand for reserves.

Variable depending on how far is the

aggregate supply of reserves to the

right of the point of satiation of

demand for reserves.

Very limited, especially with wide

corridor.

Parsimonious floor

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

19

to the real economy, neither the banking system’s liquidity nor the level of excess reserves are

correlated with the transmission of policy rates to nonfinancial corporations (NFCs) or household

loan rates. Relatedly, Lane, 2023

b indicates that the changes in credit volumes in the euro area

appear stronger during the ongoing tightening cycle than during the previous tightening cycles,

alleviating concerns that such transmission may be impeded by high bank liquidity.

Box 2. The (Non-)Impact of Bank Liquidity on Monetary Policy Transmission

Monetary policy transmits to the real economy primarily through its impact on the interest rates

relevant for economic agents (such as bank deposit and loan rates). Those interest rates effect

the real economy via several economic channels, such as the standard neoclassical interest rate

channel, the income channel, the balance sheet channel, and the banking channel (see

Beyer

and others, 2024 for a description of the channels and Mishkin, 1996, Boivin and others, 2010,

and references therein for a more detailed discussion).

The tightening cycle that the ECB initiated in 2022 represents a real-life case of monetary policy

tightening under high bank liquidity and excess reserves. One can therefore assess whether this

environment was associated with impeded transmission, by comparing the transmission of

monetary policy to interest rates during this cycle to that during the previous (2005) tightening

cycle and by examining cross-country evidence on the association between bank liquidity and

excess reserves vs. the strength of the transmission.

For bank rates, the transmission to deposits rates, particularly for household and corporate

overnight deposits (O-HH and O-NFC, respectively) and term household deposits (T-HH), seems

weaker this cycle. However, the monetary policy transmission to variable-rate loan rates, which

may be more directly related to the effects of monetary policy on the real economy, appears as

strong this cycle as in the previous one.

Using cross-country data for this tightening cycle, we explore the determinants of deposit and

loan betas (Box Figure 2.1), defined as a ratio of the increase in the bank interest rates to the

increase in the policy rate, both measured cumulatively from the beginning of the tightening cycle

to the most recent observations at the time of writing (October 2023). The analysis confirms that

high bank liquidity (as measured by the LCR) may have contributed to low deposit betas but had

no effect on loan betas. Interestingly, even for the effect of bank liquidity on the deposit rates,

banks’ excess reserves per se are insignificant, indicating that excess reserves are but a part of

banks’ overall liquidity.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

20

Box Figure 2.1. Deposit and Loan Rate Betas and Banking System Liquidity Characteristics

Note: Bank deposit and loan betas are defined as a ratio of a change in bank interest rate to a change in the policy rate since the beginning of this

tightening cycle to the most recent observation (Oct 2023). Lower betas indicate weaker transmission of policy rates to bank rates.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

21

Financial Sector Footprint, Market Discipline, and Financial Stability

The corridor system, thanks to a smaller supply of reserves than in a floor system, is associated with

a smaller central bank balance sheet, which may encourage interbank market activity, enhance

market discipline, and support price discovery. In the corridor framework, the central bank supplies

reserves and banks lend and borrow these reserves between themselves to manage their daily

idiosyncratic liquidity needs. Traditionally, such interbank lending was seen as supporting market

discipline by encouraging banks to monitor each other’s conditions (and banks are considered

superior in monitoring each other as they operate in the same industry with similar business models,

Rochet and Tirole, 1996).

19

Additionally, decentralized markets enabled “price discovery”: bank-

specific interbank rates contained price signals on the borrowers’ financial health, while average

interest rates provided policymakers with information on the banking systems’ overall liquidity

conditions.

While the corridor system could engender improved liquidity management practices and interbank

a

ctivity, several recent developments and findings may mean that market discipline and price

discovery in interbank markets could be less effective than previously thought.

First, both before and especially after the GFC, much of the interbank market has moved from

unsecured lending with rates that are sensitive to borrower conditions to secured (repo) lending

where rates depend mostly on the quality of collateral (Lane, 2023a

). M

oreover, the money market

expanded to include many nonbanks. Part of these moves were related to changes in bank

regulation that impose higher capital charges on unsecured than on secured interbank exposures

and are unlikely to be reversed. The move to secured lending undermines lender banks’ incentives

to provide market discipline and focuses price discovery on collateral availability and quality rather

than on reputation or perceived balance sheet strength of borrower banks. Still, even in secured

lending, lending counterparts may exercise a degree of market discipline when they do not wish to

be reputationally connected to a failing borrower even when their financial exposure is protected by

collateral or risk costly failures-to-deliver in subsequent trades.

20

Second, even though interbank markets may provide some warning ahead of impending stress,

creditor-based market discipline is often overly discrete. Lenders may exhibit complacency in good

times but withdraw funding rapidly during stress in a run-like manner in response to rising

19

At the conceptual level, a key ingredient of the market discipline hypothesis of money markets is asymmetric information (see

Hoerova and Monnet, 2016). The interaction between banks with liquidity deficits and banks with excess liquidity in unsecured or

secured money markets leads to lower risk taking by the former either through borrowing limits or collateral requirements. However,

market discipline fails in the presence of aggregate liquidity risk and the provision of liquidity by the central bank can improve

outcomes.

20

A “failure to deliver” or simply “fail” is a situation in repo or securities lending when the counterparty responsible to deliver the

security at the end of the transaction fails to do so. It is common for financial intermediaries to commit to deliver in subsequent

trades the securities that they have temporarily pledged in repos, a phenomenon known as rehypothecation. Secured lending

connections to a failing bank may render a bank unable to retrieve the pledged securities, raising a cascade of contractual and

liquidity issues in the system.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

22

counterparty risk or due to liquidity hoarding.

21

Creditor runs on an individual bank can be

contagious and precipitate broader interbank market freezes and liquidity squeezes (Liu, 2016

).

Consequently, signals which arise from money markets, although useful, may come too late for

corrective action by supervisors and, therefore, should not substitute for timely, intensive supervision

and adequate regulation.

Third, the conditions in other markets, notably for bank’s equity and subordinated debt may provide

policymakers with information broadly comparable to that which they could elicit from interbank

market rates (Gorton and Santomero, 1990; Ashcraft, 2008).

22

Moreover, the use of interbank

market as a monitoring tool of the policymaker requires the existence of stigma in the access to

standing lending facilities or discount windows, which reduces the ability of the operational

framework to manage bank liquidity (

Anbil and Vossmeyer, 2019).

Finally, information revealed in interbank lending may not be very high and interbank markets can be

marked by risk-shifting, segmentation, and a build-up of systemic risk (Upper and Worms, 2004

and

Elliot and others, 2021).

23

For instance, under a corridor system like that of the ECB before 2008,

interbank markets tended to be surprisingly segmented with credit limits and reputation

considerations that induced banks with liquidity shortfalls to prefer private settlement of their

accounts instead of openly borrowing in the interbank market so as to not reveal potentially

compromising information (

Gaspar and others, 2008).

Importantly, floor and corridor systems may have different implications for financial stability. On the

one hand, a corridor system may not be very robust to financial market stress. As shown by

Bindseil

and Jablecki (2011), under a conventional corridor and for given transaction costs in the interbank

market, the wider the corridor, the greater the interbank market turnover (as it becomes less likely

that a bank hits either the upper or lower bound of the corridor after a liquidity shock), the smaller the

size of the balance sheet, and the greater the volatility of short-term interest rates. The choice of the

optimal width of the corridor ultimately depends, in their framework, on central banker preferences.

However, with increasing transaction costs, as to be expected in a crisis, either the width of the

21

Lender complacency in good times that can give way to abrupt “run”-like behavior in periods of stress was analyzed, for example,

in Ratnovski (2013)

. The phenomenon of liquidity hoarding for precautionary motives during financial stress periods is well

documented. For example, Acharya and Merrouche (2013), Ashcraft and others (2011), and Berrospide (2021) find evidence of

hoarding in interbank markets during the GFC and Tran and others (2023) for the Covid crisis. Liquidity hoarding can happen

because of counterparty risk (Heider and others, 2015), rollover risk (Acharya and Skeie, 2011), or asset price volatility (Gale and

Yorulmazer, 2013). Counterparty risk can increase in crisis periods because of adverse selection or because of higher credit risk

which increases banks cost of capital (Afonso, Kovner, and Schoar, 2011). Adverse selection in interbank market occurs interbank

market participants cannot differential weak banks from the rest and lenders require higher rates to participate in that market. From

a theoretical point of view, there is reasonable consensus that the ample provision of reserves by the central bank, by substituting

the private provision of liquidity, solves these problems (e.g., Gale and Yorulmazer, 2013, and

Heider and others, 2015).

22

Market discipline and price discovery that occur in markets other than the short-term funding markets are beneficial in that they

less likely to lead to disorderly bank failures. As a flip side, however, it may allow weak banks (“zombies”) to persist in the financial

system for longer. In general, this calls for more active regulatory policy intervention to deal with weak banks and overbanking

(ESRB, 2014

).

23

Risk-shifting occurs when bank shareholders maximize their returns in states of the world in which their bank and that to which it

lends have high profits, while they see their losses capped at the value of their equity when both banks fail.

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

23

corridor widens (and the allowed interest rate volatility increases, possibly with different implications

for the stability of the financial system as a whole and possibly weakened monetary policy

transmission) or the interbank market volume plumets (with a corresponding increase in the take-up

of the central bank’s standing facilities).

Moreover, the implementation of an operational framework with lean reserves such as a traditional

corridor or ceiling could increase the potential for liquidity squeezes in other short-term funding

markets such as repo and foreign exchange swap markets (Afonso and others, 2022

). This is

because, at least for U.S. banks, there is evidence of strategic complementarities in banks’ behavior

when settling interbank payments: even when reserves are abundant, banks tend to wait for

incoming payments before settling outgoing payments. This is a sign that the level of excess

reserves observed at a given point in time may not be a strong indication of abundant liquidity as

banks still hoard intraday liquidity. Although there could be many reasons for such behavior,

including liquidity regulation, the use of reserves for repo lending and FX swaps is a likely candidate

(see Afonso and others, 2022, and sources therein). Hence, the reduction of the total amount of

excess reserves could increase the chances of those markets becoming impaired.

On the other hand, although a large supply of reserves in a floor system reduces the risk of liquidity

stress in banks, it may also induce collateral shortages that can be destabilizing for nonbank

financial intermediaries (NBFIs). By allowing banks to meet HQLA needs with reserves, a floor

system reduces the risk of bank liquidity shortages and asset fire sales during periods of financial

stress, which could happen should banks need to sell illiquid assets to meet their liquidity needs (see

Afonso and others, 2023b

and references therein). This reduces the need for the activation of

emergency liquidity facilities by the central bank, which may carry stigma. Relatedly, the

intermediation of liquidity via the central bank rather than by interbank markets leads to less financial

interconnectedness between commercial banks, which reduces the scope for potentially

unpredictable contagion in the case of bank stress and failures (

Allen and Gale, 2000; Nier and

others, 2007). At the same time, the central bank bond purchases that underlie the creation of ample

reserves may result in collateral shortages in the repo markets, resulting in liquidity pressures in the

NBFIs, which typically have no direct access to central bank facilities and rely on sourcing liquidity

from commercial banks via secured (repo) money markets. The monitoring of collateral shortage

risks may be complicated by the relative opacity of the NBFI sector, including as relates to its

liquidity needs. A broad enough collateral framework can permit the central bank to tailor asset

purchases in a way that minimizes the effects of reserves creation on collateral availability, as well

as increases the price stability of a broader range of assets by making them eligible central bank

collateral.

24

Finally, given the diversity of the European banking system, with weak banks concentrated in some

jurisdictions, a system that relies on an active interbank market to address idiosyncratic liquidity

shocks (i.e., a corridor system with a structural liquidity shortage) may deliver very different bank

24

An eventual scarcity of collateral could also be remedied if the ECB were to start selling its own bills, as many other central banks

currently do (e.g., Central Bank of Chile and Swiss National Bank).

IMF WORKING PAPERS

The ECB’s Future Monetary Policy Operational Framework

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

24

liquidity conditions across euro area counties even outside of crisis periods. This is because the

demand for bank reserves can be different from country to country even with uniform liquidity

regulations and similar fundamentals because, among other factors, the level of trust that exists

among participating banks varies across countries. In particular, in countries with a past of frequent

bank failures and stress, a lower level of trust among banks ensues, which decreases the

participation in interbank markets and increases the reliance on central bank liquidity (

Allen and

others, 2022). Hence, the return to a corridor framework may exacerbate the unequal distribution of

bank reserves across the euro area and raise the risk of liquidity shortages that could be amplified

via self-fulfilling runs into broader systemic distress. Though a floor system would mitigate these

concerns, these fragmentation risks nevertheless underscore the need to make faster progress

toward the banking union as the ECB’s balance sheet winds down with QT and the transition to the

steady state operational framework proceeds. Still, from a financial stability perspective, the choice

between retaining the current floor system (or moving to a parsimonious floor with less abundant

reserves) or moving to a corridor framework with lean reserves should also consider the benefits of