International

Narcotics Control

Strategy Report

Volume II

Money Laundering

March 2021

United States Department of State

Bureau of International Narcotics

and Law Enforcement Affairs

International

Narcotics Control

Strategy Report

Volume II

Money Laundering

March 2021

United States Department of State

Bureau of International Narcotics

and Law Enforcement Affairs

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

2

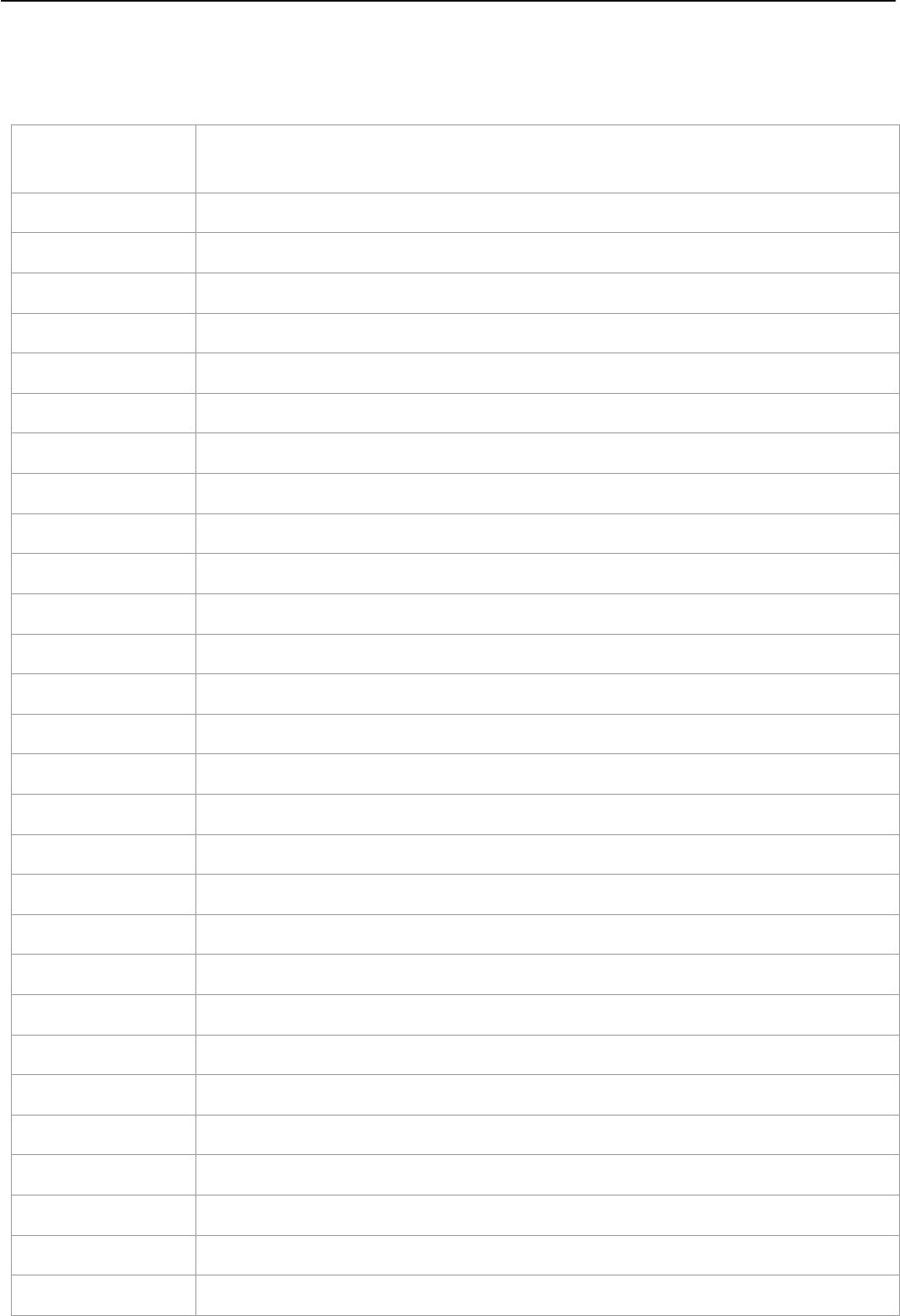

Table of Contents

Common Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................... 5

Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................................... 8

Legislative Basis and Methodology for the INCSR ................................................................................................. 13

Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................... 15

Training Activities ...................................................................................................................................................... 18

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB) .................................................................................... 18

Department of Homeland Security ........................................................................................................................... 19

Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) ........................................................................................................................... 19

Immigration and Customs Enforcement Homeland Security Investigations (ICE HSI) .................................... 19

Department of Justice ................................................................................................................................................ 20

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) ............................................................................................................... 20

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) ..................................................................................................................... 20

Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development, Assistance and Training (OPDAT) .......................................... 21

Department of State ................................................................................................................................................... 22

Department of the Treasury ...................................................................................................................................... 25

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) ................................................................................................ 25

Internal Revenue Service, Criminal Investigations (IRS-CI) ................................................................................. 25

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) .................................................................................................. 26

Office of Technical Assistance (OTA) ....................................................................................................................... 26

Comparative Table Key ............................................................................................................................................. 28

Comparative Table ..................................................................................................................................................... 30

Afghanistan ................................................................................................................................................................. 35

Albania ........................................................................................................................................................................ 37

Algeria ......................................................................................................................................................................... 39

Antigua and Barbuda ................................................................................................................................................. 41

Argentina ..................................................................................................................................................................... 43

Armenia ....................................................................................................................................................................... 45

Aruba ........................................................................................................................................................................... 48

Bahamas ...................................................................................................................................................................... 50

Barbados ...................................................................................................................................................................... 52

Belgium ........................................................................................................................................................................ 54

Belize ............................................................................................................................................................................ 55

Benin ............................................................................................................................................................................ 58

Bolivia .......................................................................................................................................................................... 60

Brazil ............................................................................................................................................................................ 62

British Virgin Islands ................................................................................................................................................. 64

Burma .......................................................................................................................................................................... 66

Cabo Verde ................................................................................................................................................................. 68

Canada ......................................................................................................................................................................... 70

Cayman Islands ................................................................................................

.......................................................... 72

China, People’s Republic of ....................................................................................................................................... 74

Colombia ..................................................................................................................................................................... 76

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

3

Costa Rica ................................................................................................................................................................... 78

Cuba ............................................................................................................................................................................. 80

Curacao ....................................................................................................................................................................... 82

Cyprus ......................................................................................................................................................................... 84

Dominica ...................................................................................................................................................................... 88

Dominican Republic ................................................................................................................................................... 90

Ecuador ....................................................................................................................................................................... 92

El Salvador .................................................................................................................................................................. 95

Georgia ........................................................................................................................................................................ 96

Ghana .......................................................................................................................................................................... 98

Guatemala ................................................................................................................................................................. 101

Guyana ...................................................................................................................................................................... 103

Haiti ........................................................................................................................................................................... 105

Honduras ................................................................................................................................................................... 107

Hong Kong ................................................................................................................................................................ 109

India ........................................................................................................................................................................... 111

Indonesia ................................................................................................................................................................... 113

Iran ............................................................................................................................................................................ 115

Italy ............................................................................................................................................................................ 117

Jamaica ...................................................................................................................................................................... 119

Kazakhstan ................................................................................................................................................................ 121

Kenya ......................................................................................................................................................................... 123

Kyrgyz Republic ....................................................................................................................................................... 125

Laos ............................................................................................................................................................................ 127

Liberia ....................................................................................................................................................................... 129

Macau ........................................................................................................................................................................ 132

Malaysia .................................................................................................................................................................... 134

Mexico ........................................................................................................................................................................ 136

Morocco ..................................................................................................................................................................... 138

Mozambique .............................................................................................................................................................. 140

Netherlands ............................................................................................................................................................... 142

Nicaragua .................................................................................................................................................................. 144

Nigeria ....................................................................................................................................................................... 147

Pakistan ..................................................................................................................................................................... 149

Panama ...................................................................................................................................................................... 151

Paraguay .................................................................................................................................................................... 153

Peru ............................................................................................................................................................................ 155

Ph

ilippines ................................................................................................................................................................. 157

Russian Federation ................................................................................................................................................... 159

St. Kitts and Nevis .................................................................................................................................................... 161

St. Lucia ..................................................................................................................................................................... 163

St. Vincent and the Grenadines ............................................................................................................................... 165

Senegal ....................................................................................................................................................................... 168

Sint Maarten ............................................................................................................................................................. 170

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

4

Spain .......................................................................................................................................................................... 172

Suriname ................................................................................................................................................................... 174

Tajikistan .................................................................................................................................................................. 176

Tanzania .................................................................................................................................................................... 177

Thailand .................................................................................................................................................................... 179

Trinidad and Tobago ............................................................................................................................................... 181

Turkey ....................................................................................................................................................................... 183

Turkmenistan ............................................................................................................................................................ 185

Ukraine ...................................................................................................................................................................... 187

United Arab Emirates .............................................................................................................................................. 190

United Kingdom ....................................................................................................................................................... 192

Uzbekistan ................................................................................................................................................................. 194

Venezuela .................................................................................................................................................................. 196

Vietnam ..................................................................................................................................................................... 198

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

5

Common Abbreviations

1988 UN Drug

Convention

1988 United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic

Drugs and Psychotropic Substances

AML

Anti-Money Laundering

APG

Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering

ARS

Alternative Remittance System

BMPE

Black Market Peso Exchange

CBP

Customs and Border Protection

CDD

Customer Due Diligence

CFATF

Caribbean Financial Action Task Force

CFT

Combating the Financing of Terrorism

CTR

Currency Transaction Report

DEA

Drug Enforcement Administration

DHS

Department of Homeland Security

DHS/HSI

Department of Homeland Security/Homeland Security Investigations

DNFBP

Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions

DOJ

Department of Justice

DOS

Department of State

EAG

Eurasian Group to Combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

EC

European Commission

ECOWAS

Economic Community of West African States

EDD

Enhanced Due Diligence

EO

Executive Order

ESAAMLG

Eastern and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group

EU

European Union

FATF

Financial Action Task Force

FBI

Federal Bureau of Investigation

FinCEN

Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

FIU

Financial Intelligence Unit

FTZ

Free Trade Zone

GABAC

Action Group against Money Laundering in Central Africa

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

6

GAFILAT

Financial Action Task Force of Latin America

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GIABA

Inter Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering

IBC

International Business Company

ILEA

International Law Enforcement Academy

IMF

International Monetary Fund

INCSR

International Narcotics Control Strategy Report

INL

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs

IRS

Internal Revenue Service

IRS-CI

Internal Revenue Service, Criminal Investigations

ISIL

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

KYC

Know-Your-Customer

MENAFATF

Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force

MER

Mutual Evaluation Report

MLAT

Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty

MONEYVAL

Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering

Measures and the Financing of Terrorism

MOU

Memorandum of Understanding

MSB

Money Service Business

MVTS

Money or Value Transfer Service

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization

NPO

Non-Profit Organization

NRA

National Risk Assessment

OAS

Organization of American States

OAS/CICAD

OAS Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission

OECD

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

OFAC

Office of Foreign Assets Control

OPDAT

Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development, Assistance and

Training

OTA

Office of Technical Assistance

PEP

Politically Exposed Person

SAR

Suspicious Activity Report

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

7

STR

Suspicious Transaction Report

TBML

Trade-Based Money Laundering

TTU

Trade Transparency Unit

UN

United Nations

UNCAC

United Nations Convention against Corruption

UNGPML

United Nations Global Programme against Money Laundering

UNODC

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

UNSCR

United Nations Security Council Resolution

UNTOC

United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

8

Definitions

419 Fraud Scheme: An advanced fee fraud scheme, known as “419 fraud” in reference to the

fraud section in Nigeria’s criminal code. This specific type of scam is generally referred to as

the Nigerian scam because of its prevalence in that country. Such schemes typically involve

promising the victim a significant share of a large sum of money, in return for a small up-front

payment, which the fraudster claims to require in order to cover the cost of documentation,

transfers, etc. Frequently, the sum is said to be lottery proceeds or personal/family funds being

moved out of a country by a victim of an oppressive government, although many types of

scenarios have been used. This scheme is perpetrated globally through email, fax, or mail.

Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT): Collective

term used to describe the overall legal, procedural, and enforcement regime countries must

implement to fight the threats of money laundering and terrorism financing.

Bearer Share: A bearer share is an equity security that is solely owned by whoever holds the

physical stock certificate. The company that issues the bearer shares does not register the owner

of the stock nor does it track transfers of ownership. The company issues dividends to bearer

shareholders when a physical coupon is presented.

Black Market Peso Exchange (BMPE): One of the most pernicious money laundering

schemes in the Western Hemisphere. It is also one of the largest, processing billions of dollars’

worth of drug proceeds a year from Colombia alone via trade-based money laundering (TBML,

defined below), “smurfing,” cash smuggling, and other schemes. BMPE-like methodologies are

also found outside the Western Hemisphere. There are variations on the schemes involved, but

generally drug traffickers repatriate and exchange illicit profits obtained in the United States

without moving funds across borders. In a simple BMPE scheme, a money launderer

collaborates with a merchant operating in Colombia or Venezuela to provide him, at a discounted

rate, U.S. dollars in the United States. These funds, usually drug proceeds, are used to purchase

merchandise in the United States for export to the merchant. In return, the merchant who

imports the goods provides the money launderer with local-denominated funds (pesos) in

Colombia or Venezuela. The broker takes a cut and passes along the remainder to the

responsible drug cartel.

Bulk Cash Smuggling: Bulk cash refers to the large amounts of currency notes criminals

accumulate as a result of various types of criminal activity. Smuggling, in the context of bulk

cash, refers to criminals’ subsequent attempts to physically transport the money from one

country to another.

Cross-border currency reporting: Per FATF recommendation, countries should establish a

currency declaration system that applies to all incoming and outgoing physical transportation of

cash and other negotiable monetary instruments.

Counter-valuation: Often employed in settling debts between hawaladars or traders. One of

the parties over-or-undervalues a commodity or trade item such as gold, thereby transferring

value to another party and/or offsetting debt owed.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

9

Currency Transaction Report (CTR): Financial institutions in some jurisdictions are required

to file a CTR whenever they process a currency transaction exceeding a certain amount. In the

United States, for example, the reporting threshold is $10,000. The amount varies per

jurisdiction. These reports include important identifying information about accountholders and

the transactions. The reports are generally transmitted to the country’s FIU.

Customer Due Diligence/Know Your Customer (CDD/KYC): The first step financial

institutions must take to detect, deter, and prevent money laundering and terrorism financing,

namely, maintaining adequate knowledge and data about customers and their financial activities.

Egmont Group of FIUs: The international standard-setter for Financial Intelligence Units

(FIUs). The organization was created with the goal of serving as a center to overcome the

obstacles preventing cross-border information sharing between FIUs.

FATF-Style Regional Body (FSRB): These bodies – which are modeled on the Financial

Action Task Force (FATF) and are granted certain rights by that organization – serve as regional

centers for matters related to AML/CFT. Their primary purpose is to promote a member

jurisdiction’s implementation of comprehensive AML/CFT regimes and implement the FATF

recommendations.

Financial Action Task Force (FATF): FATF was created by the G7 leaders in 1989 in order to

address increased alarm about money laundering’s threat to the international financial system.

This intergovernmental policy making body was given the mandate of examining money

laundering techniques and trends and setting international standards for combating money

laundering and terrorist financing.

Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU): In many countries, a central national agency responsible for

receiving, requesting, analyzing, and/or disseminating disclosures of financial information to the

competent authorities, primarily concerning suspected proceeds of crime and potential financing

of terrorism. An FIU’s mandate is backed up by national legislation or regulation. The Financial

Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is the U.S. financial intelligence unit.

Free Trade Zone (FTZ): A special commercial and/or industrial area where foreign and

domestic merchandise may be brought in without being subject to the payment of usual

customs duties, taxes, and/or fees. Merchandise, including raw materials, components, and

finished goods, may be stored, sold, exhibited, repacked, assembled, sorted, or otherwise

manipulated prior to re-export or entry into the area of the country covered by customs. Duties

are imposed on the merchandise (or items manufactured from the merchandise) only when the

goods pass from the zone into an area of the country subject to customs. FTZs may also be

called special economic zones, free ports, duty-free zones, or bonded warehouses.

Funnel Account: An individual or business account in one geographic area that receives

multiple cash deposits, often in amounts below the cash reporting threshold, and from which the

funds are withdrawn in a different geographic area with little time elapsing between the deposits

and withdrawals.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

10

Hawala: A centuries-old broker system based on trust, found throughout South Asia, the Arab

world, and parts of Africa, Europe, and the Americas. It allows customers and brokers (called

hawaladars) to transfer money or value without physically moving it, often in areas of the world

where banks and other formal institutions have little or no presence. It is used by many different

cultures, but under different names; “hawala” is used often as a catchall term for such systems in

discussions of terrorism financing and related issues.

Hawaladar: A broker in a hawala or hawala-type network.

Hundi: See Hawala

International Business Company (IBC): Firms registered in an offshore jurisdiction by a non-

resident that are precluded from doing business with residents in the jurisdiction. Offshore

entities may facilitate hiding behind proxies and complicated business structures. IBCs are

frequently used in the “layering” stage of money laundering.

Integration: The last stage of the money laundering process. The laundered money is

introduced into the economy through methods that make it appear to be normal business activity,

to include real estate purchases, investing in the stock market, and buying automobiles, gold, and

other high-value items.

Kimberly Process (KP): The Kimberly Process was initiated by the UN to keep “conflict” or

“blood” diamonds out of international commerce, thereby drying up the funds that sometimes

fuel armed conflicts in Africa’s diamond producing regions.

Layering: This is the second stage of the money laundering process. The purpose of this stage

is to make it more difficult for law enforcement to detect or follow the trail of illegal proceeds.

Methods include converting cash into monetary instruments, wire transferring money between

bank accounts, etc.

Legal Person: A company or other entity that has legal rights and is subject to obligations. In

the FATF Recommendations, a legal person refers to a partnership, corporation, association, or

other established entity that can conduct business or own property, as opposed to a human being.

Mutual Evaluation (ME): All FATF and FSRB members have committed to undergoing

periodic multilateral monitoring and peer review to assess their compliance with FATF’s

recommendations. Mutual evaluations are one of the FATF’s/FSRB’s primary instruments for

determining the effectiveness of a country’s AML/CFT regime.

Mutual Evaluation Report (MER): At the end of the FATF/FSRB mutual evaluation process,

the assessment team issues a report that describes the country’s AML/CFT regime and rates its

effectiveness and compliance with the FATF Recommendations.

Mobile Payments or M-Payments: An umbrella term that generally refers to the growing use

of cell phones to credit, send, receive, and transfer money and virtual value.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

11

Natural Person: In jurisprudence, a natural person is a real human being, as opposed to a legal

person (see above). In many cases, fundamental human rights are implicitly granted only to

natural persons.

Offshore Financial Center: Usually a low-tax jurisdiction that provides financial and

investment services to non-resident companies and individuals. Generally, companies doing

business in offshore centers are prohibited from having clients or customers who are resident in

the jurisdiction. Such centers may have strong secrecy provisions or minimal identification

requirements.

Over-invoicing: When money launderers and those involved with value transfer, trade-fraud,

and illicit finance misrepresent goods or services on an invoice by indicating they cost more than

they are actually worth. This allows one party in the transaction to transfer money to the other

under the guise of legitimate trade.

Politically Exposed Person (PEP): A term describing someone who has been entrusted with a

prominent public function, or an individual who is closely related to such a person. This

includes the heads of international organizations.

Placement: This is the first stage of the money laundering process. Illicit money is disguised or

misrepresented, then placed into circulation through financial institutions, casinos, shops, and

other businesses, both local and abroad. A variety of methods can be used for this purpose,

including currency smuggling, bank transactions, currency exchanges, securities purchases,

structuring transactions, and blending illicit with licit funds.

Shell Company: An incorporated company with no significant operations, established for the

sole purpose of holding or transferring funds, often for money laundering purposes. As the name

implies, shell companies have only a name, address, and bank accounts; clever money launderers

often attempt to make them look more like real businesses by maintaining fake financial records

and other elements. Shell companies are often incorporated as IBCs.

Smurfing/Structuring: A money laundering technique that involves splitting a large bank

deposit into smaller deposits to evade financial transparency reporting requirements.

Suspicious Transaction Report/Suspicious Activity Report (STR/SAR): If a financial

institution suspects or has reasonable grounds to suspect that the funds involved in a given

transaction derive from criminal or terrorist activity, it is obligated to file a report with its

national FIU containing key information about the transaction. In the United States, SAR is the

most common term for such a report, though STR is used in most other jurisdictions.

Tipping Off: The disclosure of the reporting of suspicious or unusual activity to an individual

who is the subject of such a report, or to a third party. The FATF Recommendations call for

such an action to be criminalized.

Trade-Based Money Laundering (TBML): The process of disguising the proceeds of crime

and moving value via trade transactions in an attempt to legitimize their illicit origin.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

12

Trade Transparency Unit (TTU): TTUs examine trade between countries by comparing, for

example, the export records from Country A and the corresponding import records from Country

B. Allowing for some recognized variables, the data should match. Any wide discrepancies

could be indicative of trade fraud (including TBML), corruption, or the back door to

underground remittance systems and informal value transfer systems, such as hawala.

Under-invoicing: When money launderers and those involved with value transfer, trade fraud,

and illicit finance misrepresent goods or services on an invoice by indicating they cost less than

they are actually worth. This allows the traders to settle debts between each other in the form of

goods or services.

Unexplained Wealth Order (UWO): A type of court order to compel someone to reveal the

sources of their unexplained wealth. UWOs require the owner of an asset to explain how he or

she was able to afford that asset. Persons who fail to provide a response may have assets seized

or may be subject to other sanctions.

UNSCR 1267: UN Security Council Resolution 1267 and subsequent resolutions require all UN

member states to take specific measures against individuals and entities associated with the

Taliban and al-Qaida. The “1267 Committee” maintains a public list of these individuals and

entities, and countries are encouraged to submit potential names to the committee for

designation.

UNSCR 1373: UN Security Council Resolution 1373 requires states to freeze without delay the

assets of individuals and entities associated with any global terrorist organization. This is

significant because it goes beyond the scope of Resolution 1267 and requires member states to

impose sanctions against all terrorist entities.

Virtual Currency: Virtual currency is an internet-based form of currency or medium of

exchange, distinct from physical currencies or forms of value such as banknotes, coins, and gold.

It is electronically created and stored. Some forms are encrypted. They allow for instantaneous

transactions and borderless transfer of ownership. Virtual currencies generally can be purchased,

traded, and exchanged among user groups and can be used to buy physical goods and services,

but can also be limited or restricted to certain online communities, such as a given social network

or internet game. Virtual currencies are purchased directly or indirectly with genuine money at a

given exchange rate and can generally be remotely redeemed for genuine monetary credit or

cash. According to the U.S. Department of Treasury, virtual currency operates like traditional

currency, but does not have all the same attributes; i.e., it does not have legal tender status.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

13

Legislative Basis and Methodology for the INCSR

The 2021 volume on Money Laundering is a legislatively-mandated section of the annual

International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), in accordance with section 489 of the

Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (the “FAA,” 22 U.S.C. § 2291).

1

The FAA requires the Department of State to produce a report on the extent to which each

country or entity that received assistance under chapter 8 of Part I of the Foreign Assistance Act

in the past two fiscal years has “met the goals and objectives of the United Nations Convention

Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances” (“1988 UN Drug

Convention”) (FAA § 489(a)(1)(A)).

In addition to identifying countries in relation to illicit narcotics, the INCSR is mandated to

identify “major money laundering countries” (FAA §489(a)(3)(C)). The INCSR also is required

to report findings on each country’s adoption of laws and regulations to prevent narcotics-related

money laundering (FAA §489(a)(7)(C)). This volume is the section of the INCSR that reports

on money laundering and country efforts to address it.

The statute defines a “major money laundering country” as one “whose financial institutions

engage in currency transactions involving significant amounts of proceeds from international

narcotics trafficking” (FAA § 481(e)(7)). The determination is derived from the list of countries

included in INCSR Volume I (which focuses on narcotics) and other countries proposed by U.S.

government experts based on indicia of significant drug-related money laundering activities.

Given money laundering activity trends, the activities of non-financial businesses and

professions or other value transfer systems are given due consideration.

Inclusion in Volume II is not an indication that a jurisdiction is not making strong efforts to

combat money laundering or that it has not fully met relevant international standards. The

INCSR is not a “black list” of jurisdictions, nor are there sanctions associated with it. The U.S.

Department of State regularly reaches out to counterparts to request updates on money

laundering and AML efforts, and it welcomes information.

The following countries/jurisdictions have been identified this year:

Major Money Laundering Jurisdictions in 2020:

Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Armenia, Aruba, Bahamas,

Barbados, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, British Virgin Islands, Burma, Cabo Verde,

Canada, Cayman Islands, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Curacao, Cyprus, Dominica,

1

This 2021 report on Money Laundering is based upon the contributions of numerous U.S. government agencies and international

sources. Specifically, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Terrorist

Financing and Financial Crimes, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Internal Revenue Service, Office of the Comptroller of the

Currency, and Office of Technical Assistance; Department of Homeland Security’s Immigrations and Customs Enforcement and

Customs and Border Protection; Department of Justice’s Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section, Office of International

Affairs, Drug Enforcement Administration, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and Office for Overseas Prosecutorial Development,

Assistance, and Training. Also providing information on training and technical assistance is the independent Board of Governors of

the Federal Reserve System.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

14

Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Georgia, Ghana, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti,

Honduras, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kyrgyz

Republic, Laos, Liberia, Macau, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Mozambique, Netherlands,

Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Russia, St. Kitts and Nevis,

St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Senegal, Sint Maarten, Spain, Suriname, Tajikistan,

Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Arab

Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

15

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted governments and commercial activity around the globe in

2020. Onsite supervisory and audit programs were delayed or cancelled. Financial institutions

and businesses adjusted their functions and adopted new methods of communicating and

conducting transactions. Yet, despite the contraction of the global economy, the flow of illicit

money continued. Criminals not only continued to perpetrate traditional financial crimes but

devised new ways to exploit the pandemic through counterfeiting essential goods and telephone

and email scams promoting health or medical products.

The 2021 edition of the Congressionally mandated “International Narcotics Control Strategy

Report, Volume II: Money Laundering” focuses on the exposure to this threat in the specific

context of narcotics-related money laundering. The report reviews the anti-money laundering

(AML) legal and institutional infrastructure of jurisdictions and highlights the most significant

steps each has taken to improve its AML regime. It also describes key vulnerabilities and

deficiencies of these regimes, identifies each jurisdiction’s capacity to cooperate in international

investigations, and highlights the United States’ provision of AML-related technical assistance.

The United States is a founding member of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and has

worked within the organization and with partner countries and FATF-style regional bodies to

promote compliance with the FATF 49 Recommendations. It has also supported, through

technical assistance and other means, the development and implementation of robust national-

level AML regimes around the world.

Corruption continues to flourish in many parts of the world, facilitating organized criminal

enterprises and money laundering. Although the potential for corruption exists in all countries,

weak political will, ineffective institutions, or deficient AML infrastructure heighten the risk that

it will occur. The 2021 report highlights actions several governments are taking to more

effectively address corruption and its links to money laundering. While legislative and

institutional reforms are an important foundation for preventing corruption, robust and consistent

enforcement is also key. In 2020, the Kyrgyz Republic passed an anticorruption strategy for

2021-2024, which includes plans to better repatriate stolen assets. The Government of

Mozambique adopted a new asset recovery bill as well as unique account numbers for

individuals to use in banks nationwide. Afghanistan issued regulations implementing asset

forfeiture for corruption cases in the country’s first such asset-recovery regulation and, in

October 2020, Afghan officials announced they prevented the illegal transfer of $1.6 million

over the preceding four months.

Increasing the transparency of beneficial ownership remains a central focus of AML efforts,

appearing in coverage of some recent high-level corruption allegations in the media. Shell

companies, many located in offshore centers with secrecy stipulations, are used by drug

traffickers, organized criminal organizations, corrupt officials, and some regimes to launder

money and evade sanctions. “Off-the shelf” international business companies (IBCs), which

can be purchased via the internet, remain a significant concern by effectively providing

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

16

anonymity to true beneficial owners. While this report reflects that beneficial ownership

transparency remains a vulnerability in many jurisdictions, it also highlights important steps

taken by many governments.

In a major anticorruption and AML milestone for the United States, the U.S. Congress passed the

Corporate Transparency Act in 2020. Once completed, regulations to implement the act will

require corporations and limited liability companies to disclose their beneficial owners to the

U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which

will make the information available to appropriate government entities and financial institutions.

The United States was not the only jurisdiction to take action in 2020. In The Bahamas, the

country’s Attorney General’s Office and Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) implemented a secure

search system for accessing online information on beneficial ownership of legal entities

registered in the country. Belize enacted legislation to give effect to tax transparency

obligations. Since October 2020, the names of subscribers, registered offices, year-end share

capital, and nature of business of companies in the Cayman Islands are publicly available. A

new law in the Netherlands requires all corporate and other legal entities to list their ultimate

beneficial owners in a transparent register. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) Council of

Ministers (Cabinet) issued a resolution requiring declaration of beneficial ownership, shareholder

disclosure, and timely updating of ownership information.

As new technologies emerge, crimes like money laundering evolve, posing new challenges for

societies, governments, and law enforcement. The rapid growth of global mobile payments (m-

payments) and virtual currencies demands particular attention in the AML sphere. The use of

mobile telephony to send and receive money or credit continues to exceed the rate of bank

account ownership in many parts of the world. The risk that criminal and terrorist organizations

will co-opt m-payment services is real, particularly as the services can manifest less than optimal

financial transparency.

Virtual currencies are growing in popularity and expanding their reach. In 2020, The Bahamas

launched the Sand Dollar, the world’s first central bank-backed digital currency. The Sand

Dollar is stored in a non-interest-bearing digital wallet accessible through mobile devices. China

is currently piloting a central bank-backed digital currency known as the eCNY or eCNY Digital

Currency Electronic Payment. In March 2020, the Supreme Court of India removed an earlier

government ban on trading in virtual currencies.

A growing number of jurisdictions are responding to the challenges posed by the rapid

development of such anonymous e-payment methodologies. In 2020, the Prosecution Service of

Georgia created a new cybercrime department and is in the process of developing virtual

currency seizure guidelines for law enforcement. The Cayman Islands passed new legislation

identifying its Monetary Authority as the AML supervisor of virtual asset service providers. The

Peruvian Financial Intelligence Unit began supervising virtual currency exchanges and launched

a risk analysis of virtual currencies, which will inform the drafting of a specific regulation.

Antigua and Barbuda adopted legislation to introduce warrants for law enforcement to search the

contents of electronic devices. The United Kingdom updated its AML regulations to cover

virtual assets. In Thailand, the government held public hearings on proposed legislative

amendments designed to cover financial technology service providers. Canada passed regulatory

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

17

amendments that now require money service businesses (MSBs) dealing in virtual currencies to

comply with AML requirements and register with the Financial Transactions and Reports

Analysis Centre (FINTRAC). Foreign MSBs also must fulfill new AML compliance measures

and register with FINTRAC.

Although new technologies are gaining popularity, money launderers continue to use free trade

zones and gaming enterprises to launder illicit funds. Trade-based money laundering (TBML),

in particular, is a long-standing area of concern. Trade-based systems act as a kind of parallel

method of transferring money and value around the world. Because systems such as hawala, the

black market peso exchange, and the use of commodities such as gold and diamonds are not

captured by many financial reporting requirements, they pose tremendous challenges for law

enforcement. These methods are often based simply on the alteration of shipping documents or

invoices, and thus are frequently undetected unless jurisdictions work together to share

information and compare documentation. The UAE now mandates hawaladars and informal

money transfer service providers formally register with its central bank. The growing network of

Trade Transparency Units (TTUs), now numbering 16 active units, has revealed the extent of

transnational TBML through the monitoring of import and export documentation. These units

focus on detecting anomalies in trade data—such as deliberate over- and under-invoicing—that

can be a powerful predictor of TBML. In recognition of this ongoing threat, a joint FATF-

Egmont Group project is developing new guidelines for the identification of possible TBML.

As political stability, democracy, and free markets depend on solvent, stable, and honest

financial, commercial, and trade systems, the continued development of effective AML regimes

consistent with international standards is vital. The United States looks forward to continuing to

work with international partners in furthering this important agenda, promoting compliance with

international norms and strengthening capacities globally to prevent and combat money

laundering.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

18

Training Activities

During 2020, the United States continued its endeavors to strengthen the capacity of our partners

in the fight against money laundering despite the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although

some activities were curtailed or completed remotely, U.S. regulatory agencies and law

enforcement continued to share best practices and provide training and technical assistance on

money laundering countermeasures, financial investigations, and related issues to their

counterparts around the globe. The programs built the capacity of our partners and provided the

necessary tools to recognize, prevent, investigate, and prosecute money laundering, financial

crimes, terrorist financing, and related criminal activity. U.S. agencies provided instruction

directly or through other agencies or implementing partners, unilaterally or in collaboration with

foreign counterparts, and with either a bilateral recipient or in multijurisdictional training

exercises. The following is a representative, but not necessarily exhaustive, overview of the

capacity building provided and organized by sponsoring agencies.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB)

The FRB conducts a Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) and OFAC compliance program review as part of

its regular safety and soundness examination. These examinations are an important component

in the United States’ efforts to detect and deter money laundering and terrorist financing. The

FRB monitors its supervised financial institutions’ conduct for BSA and OFAC

compliance. Internationally, during 2020, the FRB did not conduct any in person AML/CFT

international trainings or technical assistance missions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It did

conduct remote training programs for over 300 participants.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

19

Department of Homeland Security

Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

Both the International Operations Directorate and International Support Directorate of CBP

provide international training programs and/or technical assistance. CBP did not conduct any

AML training or technical assistance programs in calendar year 2020.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement Homeland Security

Investigations (ICE HSI)

During 2020, ICE HSI provided critical training and technical assistance to the United States’

foreign law enforcement partners. In Canada, ICE HSI worked with Canadian law enforcement

agencies to provide training on cryptocurrency, the dark web, asset forfeiture, and financial

investigative techniques. ICE HSI deployed personnel to the Canada Border Services Agency’s

Trade Fraud and Trade Based Money Laundering Center as well as with Public Safety Canada

and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Financial Crimes Coordination Center to increase

information sharing in financial investigations and combatting money laundering. ICE HSI

partnered with Caribbean law enforcement agencies to provide training on U.S.-based firearm

export violations and its ties to narcotic smuggling within the United States. In Asia and Europe,

ICE HSI trained bank officials and law enforcement partners in Malaysia and France on the ties

between cryptocurrency money laundering and those engaged in crimes against children, child

exploitation, and overall TBML. In South America, ICE HSI assisted the Peruvian National

Police in investigating TBML occurring within Peru and trained Colombian military, tax and

customs, and financial investigative offices on money laundering and contraband targeting to

identify and disrupt illicit financial activity taking place along the country's remote coasts.

Finally, in Central America, ICE HSI provided training on cryptocurrency investigations to

Panamanian partners within the Panama National Police, its Public Ministry, and other

Panamanian law enforcement bodies.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

20

Department of Justice

Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

The Office of Domestic Operations, Financial Investigations Section (ODF) coordinates DEA’s

efforts to target the financial aspects of transnational criminal organizations across domestic and

foreign offices. ODF works in conjunction with DEA field offices, foreign counterparts, and the

interagency community to provide guidance and support on financial investigations and offers a

variety of investigative tools and oversight on DEA’s undercover financial investigations. ODF

also liaises with the international law enforcement community to further cooperation between

countries and investigative efforts, to include prosecution of money launderers, the seizure of

assets, and denial of revenue.

ODF regularly briefs and educates United States government officials and diplomats, foreign

government officials, and military and law enforcement counterparts regarding the latest trends

in money laundering, narcoterrorism financing, international banking, offshore corporations,

international wire transfer of funds, and financial investigative tools and techniques.

ODF also conducts training for DEA field offices, both domestic and foreign, as well as for

foreign counterparts, in order to share strategic ideas and promote effective techniques in

financial investigations. During 2020, ODF participated in and led a number of virtual

workshops and strategy sessions focused on COVID-19 money laundering trends, TBML,

private sector engagement, virtual currency, and investigative case coordination. Also during

2020, DEA participated in virtual money laundering training courses and workshops with a

number of international partners, to include but not limited to: Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica,

Guatemala, Mexico, and Canada.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

The FBI provides training and/or technical assistance to national law enforcement personnel

globally. Training and technical assistance programs enhance host country law enforcement’s

capacity to investigate and prosecute narcotics-related money laundering crimes. The FBI has

provided workshops introducing high-level money laundering techniques used by criminal and

terrorist organizations. The training may focus on topics such as a foundational understanding of

drug trafficking investigative and analytical techniques and tactics, money laundering and public

corruption, or terrorism financing crimes and their relationship to drug trafficking as a support

for terrorism activities. In 2020, the FBI provided financial crime and money laundering training

to Argentina, Antigua and Barbuda, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican

Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Hungary, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama,

Peru, Paraguay, and Trinidad and Tobago. The FBI also participated in training provided

through UNODC.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

21

Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development, Assistance

and Training (OPDAT)

In 2020, with funding from INL, OPDAT provided expert AML assistance throughout the world

consistent with international standards and in furtherance of U.S. national security:

Africa

In The Gambia, OPDAT assisted in pursuing foreign assets of the corrupt former president,

including assistance to the USDOJ’s Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section to initiate

civil forfeiture proceedings on a multimillion-dollar property in Maryland. Additionally, in late

2020, FBI Special Agents returned to Ghana to continue case-based mentoring with

investigators.

Asia and the Pacific

In the Maldives, OPDAT-mentored prosecutors secured a 20-year sentence of the former vice

president for money laundering and corruption. In Indonesia, OPDAT worked with the

anticorruption commission and provided training to over 1,200 journalists, academics, civil

servants, and others on how money is laundered through corporations and the role the media can

and should play. In Nepal, OPDAT has continually advocated for the creation of specialized

units, including AML prosecutors. In Bangladesh, OPDAT held an anticorruption/AML virtual

program for approximately 50 prosecutors and law enforcement officers. In Burma, OPDAT

drafted an AML concept note and continued promoting a set of written police prosecutor

guidelines for AML cases, which reflect international standards.

Europe

Through regional and bilateral workshops, as well as extensive case-based mentoring, in 2020

OPDAT developed the financial investigation skills of police and prosecutors throughout the

Western Balkans, including Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia,

Montenegro, and Serbia, as well as in Bulgaria, Latvia, and Romania; this capacity building has

resulted in significant AML successes. OPDAT provided AML instruction throughout the

region to judges on reviewing complex financial evidence and to journalists and civil society

representatives on conducting open source financial investigations. OPDAT also assisted the

government of Malta to enact AML reforms necessary to comply with international standards.

Western Hemisphere

In Mexico, OPDAT provided case-based mentoring to prosecutors handling AML cases, as well

as support to the Mexican Congress. These engagements have resulted in significant arrests and

prosecutions of cartel members and leaders. OPDAT also provided regular AML and asset

forfeiture assistance and mentoring to Guatemalan, Honduran, and Salvadoran prosecutors,

investigators, judges, and AML units, and led regional efforts to share best practices and promote

increased regional sharing of information on these topics. Finally, OPDAT hosted a Pan

American AML/CFT Seminar Series with the goal of strengthening cross-border cooperation

throughout the Americas against money laundering and terrorist financing. More than 250

prosecutors, judges, and analysts participated.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

22

Department of State

The Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL) works

to keep Americans safe by countering crime, illegal drugs, and instability abroad. Through its

international technical assistance and training programs, in coordination with other Department

bureaus, U.S. government agencies, and multilateral organizations, INL addresses a broad range

of law enforcement and criminal justice areas, including developing strong AML regimes around

the world.

INL and its partners design programs and provide AML training and technical assistance to

countries that demonstrate the political will to develop viable AML regimes. The strategic

objective is to disrupt the activities of transnational criminal organizations and drug trafficking

organizations by disrupting their financial resources. INL funds many of the regional training

and technical assistance programs offered by U.S. law enforcement agencies, including those

provided at the INL-managed International Law Enforcement Academies.

Examples of INL sponsored programs include:

Europe and Asia

Afghanistan: Through agreements with the Department of Justice and UNODC, INL supported

mentoring and technical assistance on AML/CFT to Afghan investigators and prosecutors

engaged in processing corruption, major crimes, narcotics, and national security cases.

Central Asia Region: The United States supports a regional AML/CFT advisor to provide

training and mentoring to FIU and prosecutorial personnel in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic,

Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan in order to improve the effectiveness of national

AML/CFT frameworks.

Europe: INL is working closely with partners in Europe to detect and stop the flow of illicit

funds derived from criminal enterprises, often involving corruption and organized crime. INL is

working closely with authorities in Latvia, Slovak Republic, Cyprus, Malta, Bulgaria, and

Romania, among others, to enhance their efforts to investigate financial crimes, including money

laundering and other crimes related to corruption and organized crime.

Laos: The United States supported training for the Lao Anti-Money Laundering Intelligence

Office, Customs, police, prosecutors, and judges on financial investigations, AML, bulk-cash

smuggling, and risk identification and assessment.

Mongolia: The United States supported training on financial crimes and AML for Mongolian

law enforcement, prosecutors, and FIU staff, as well as the provision of specialized software to

facilitate data collection, management, analysis, and workflow.

Philippines: The USG has supported training for AMLC on areas including the collection of

electronic evidence, casino financial crimes, counter terrorism financing, case preparation, asset

management, database support, and investigations.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

23

Western Hemisphere

Caribbean: The United States partnered with the Caribbean Community Implementation

Agency for Crime and Security (CARICOM IMPACS) to host a three-day virtual Caribbean

Financial Crimes Technical Working Group covering civil asset forfeiture, financial crimes

legislation, money laundering, electronic evidence, and regional financial crimes and case

studies. Participating countries included The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada,

Guyana, Jamaica, Haiti, St. Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines,

Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.

The United States supported UNODC trainings on TBML for 1,247 Caribbean officials and an

AML training led by Trinidad and Tobago for an additional 573 Caribbean officials.

Central America: In El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, INL supports the deployment of

Department of Justice resident legal advisors who focus on financial crimes. INL also works

with specialized units in the offices of the attorneys general in each of these countries to provide

mentoring, advice, and the skills needed to investigate and prosecute crimes with a money

laundering nexus. INL interagency agreements with the Department of Justice support law

enforcement and prosecutorial coordination through quarterly meetings and technical

assistance. In November 2020, these coordination efforts brought together gang prosecutors and

investigators from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and the United States in a one-

week coordinated law enforcement action that resulted in criminal charges in Central America

against more than 700 members of transnational criminal organizations. To ensure continuity in

justice sector training during the COVID-19 pandemic, INL supported increased online training

opportunities for justice sector actors.

Similarly, INL support to U.S. ICE-vetted transnational criminal investigative units in El

Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama helps disrupt and dismantle transnational criminal

organizations and investigate crimes, including money laundering.

Colombia: INL provides training, equipment, and case-based mentoring to prosecutors and

investigators in the Attorney General’s Office. These lines of effort are designed to prioritize

complex, transnational organized crime cases with the goal of prosecuting money laundering and

disrupting financing for drug trafficking and other organized crime activities. Further, INL

supports the Special Assets Entity in developing procedures to recover assets forfeited using

non-conviction-based forfeiture procedures. Additionally, INL supports training and technical

assistance for Colombian judicial actors to make informed decisions in complex AML cases.

Ecuador: Ecuadorian cooperation with U.S. law enforcement agencies improved due to

increased United States technical assistance for Ecuador’s FIU, the Financial and Economic

Analysis Unit (UAFE) and the formation of a vetted AML unit comprised of the Attorney

General’s Office, UAFE, and National Police personnel.

Peru: The United States supported AML trainings on virtual currencies and financial

technology.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

24

Suriname: The FIU is developing further technical skills through INL-supported training

programs.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

25

Department of the Treasury

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)

FinCEN is the United States FIU, administrator of the Bank Secrecy Act, and primary regulator

of AML/CFT activity. FinCEN conducts bilateral and multilateral training and assistance with

foreign counterpart FIUs and various domestic and international agencies and departments. This

work includes but is not limited to: multilateral information sharing projects focused on specific

topics of interest among jurisdictions; analyst exchange programs and training; and programs

that enhance analytic capabilities and strengthen operational collaboration to identify, track, and

develop actionable operational intelligence. In 2020, FinCEN did a presentation to the FATF

Virtual Asset Contact Group (which included participation across all FATF regions); participated

in the UNODC Southeast Asia Cryptocurrency Working Group meeting and training, which was

focused especially on Southeast Asia; the United States-United Kingdom Virtual Currency

Roundtable; and a training program for the Kuwait FIU on the role of an FIU in SAR analysis

and assistance to law enforcement.

Internal Revenue Service, Criminal Investigations (IRS-CI)

IRS-CI provides training and technical assistance to international law enforcement officers in

detecting and investigating financial crimes involving tax, money laundering, terrorist financing,

and public corruption. With funding provided by the DOS, DOJ, and other sources, IRS-CI

delivers training through agency and multi-agency technical assistance programs.

IRS-CI delivered the Inter-Agency Cooperation in Financial Investigations course at the ILEA

Regional Training Center in Accra, Ghana in March 2020. The training was co-delivered with

DEA instructors.

The IRS-CI international training program created a virtual training alternative to meet the needs

of our training partners abroad. In 2020, IRS-CI offered webinars focused on a variety of

financial techniques and case studies involving financial crimes. These webinars benefited

criminal investigators and their supervisors, tax enforcement officials, and government

prosecutors in combating serious crimes. Current webinar offerings include the following topics:

International Public Corruption with Foreign Corrupt Practices Act and Money Laundering

Violations Case Study; TBML via Value Added Tax Fraud Case Study; PEP Case Study;

Narcotics and the Dark Web Case Study; and Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Cyber

Hack and Cryptocurrency Case Study.

The IRS-CI international training program delivered webinars for government officials in Belize,

Canada, Cayman Islands, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico,

Panama, and Paraguay.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

26

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)

The U.S. Department of Treasury’s OCC charters, regulates, and supervises all national banks

and federal savings associations in the U.S. The OCC’s goal is to ensure these institutions

operate in a safe and sound manner and comply with all laws and regulations, including the Bank

Secrecy Act, as well as consumer protection laws and implementing regulations. The OCC also

sponsors several initiatives to provide AML/CFT training to foreign banking supervisors.

However, in 2020, due to COVID-19, the OCC was not able offer its annual AML/CFT School,

designed specifically for foreign banking supervisors, to increase their knowledge of money

laundering and terrorism financing typologies and improve their ability to examine and enforce

compliance with national laws. OCC officials met with representatives from foreign law

enforcement authorities, FIUs, and AML/CFT supervisory agencies to discuss the U.S.

AML/CFT regime, the agencies’ risk-based approach to AML/CFT supervision, examination

techniques and procedures, and enforcement actions. The OCC is preparing to offer virtual

AML/CFT training to foreign regulators in 2021.

Office of Technical Assistance (OTA)

Each of OTA’s five teams – Revenue Policy and Administration, Budget and Financial

Accountability, Government Debt and Infrastructure Finance, Banking & Financial Services, and

Economic Crimes – focuses on particular areas to establish strong financial sectors and sound

public financial management in developing and transition countries. OTA follows a number of

guiding principles to complement its holistic approach to technical assistance and supports self-

reliance by equipping countries with the knowledge and skills required to reduce dependence on

international aid and achieve sustainability. OTA is selective and only works with governments

that are committed to reform – reform that counterparts design and own – and to applying U.S.

assistance effectively. OTA works side-by-side with counterparts through mentoring and on-the-

job training, which is accomplished through co-location at a relevant government agency.

OTA’s activities are funded by a direct appropriation from the U.S. Congress as well as transfers

from other U.S. agencies, notably the U.S. Department of State and USAID.

The mission of the OTA Economic Crimes Team (ECT), in particular, is to provide technical

assistance to help foreign governments develop and implement internationally compliant

AML/CFT regimes. In this context, the ECT also addresses underlying predicate crimes,

including corruption and organized crime. To ensure successful outcomes, ECT engagements

are based on express requests from foreign government counterparts. The ECT responds to a

request with an onsite assessment by ECT management, which considers the jurisdiction’s

noncompliance with international standards and the corresponding needs for technical assistance,

as well as the willingness by the counterparts to engage in an active partnership with the ECT to

address those deficiencies.

An ECT engagement, tailored to the specific conditions of the jurisdiction, may involve

placement of a resident advisor and/or utilization of intermittent advisors under the coordination

of a team lead. The scope of ECT technical assistance is broad and can include awareness-

raising aimed at a range of AML/CFT stakeholders; improvements to an AML/CFT legal

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

27

framework, including legislation, regulations, and formal guidance; and improvement of the

technical competence of stakeholders. The range of on-the-job training provided by the ECT is

equally broad and includes, among other topics, supervisory techniques for relevant regulatory

areas; analytic and financial investigative techniques; cross-border currency movement and

TBML; asset seizure, forfeiture, and management; and the use of interagency financial crimes

working groups.

In 2020, following these principles and methods, the ECT delivered technical assistance to

Angola, Argentina, Belize, Botswana, Cabo Verde, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Estonia, Iraq,

Latvia, the Maldives, Mongolia, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka, and Zambia.

INCSR 2021 Volume II Money Laundering

28

Comparative Table Key

The comparative table following the Glossary of Terms below identifies the broad range of

actions, effective as of December 31, 2020, that jurisdictions have, or have not, taken to combat

drug money laundering. This reference table provides a comparison of elements that include

legislative activity and other identifying characteristics that can have a relationship to a

jurisdiction’s money laundering vulnerability. For those questions relating to legislative or

regulatory issues, “Y” is meant to indicate legislation has been enacted to address the

captioned items. It does not imply full compliance with international standards.

Glossary of Terms

• “Criminalized Drug Money Laundering”: The jurisdiction has enacted laws

criminalizing the offense of money laundering related to illicit proceeds generated by the

drug trade.

• “Know-Your-Customer Provisions”: By law or regulation, the government requires

banks and/or other covered entities to adopt and implement Know-Your-

Customer/Customer Due Diligence (KYC/CDD) programs for their customers or

clientele.

• “Report Suspicious Transactions”: By law or regulation, banks and/or other covered

entities are required to report suspicious or unusual transactions (STRs) to designated

authorities.

• “Maintain Records over Time”: By law or regulation, banks and other covered entities

are required to keep records, especially of large or unusual transactions, for a specified

period of time, e.g., five years.

• “Cross-Border Transportation of Currency”: By law or regulation, the jurisdiction has

established a declaration or disclosure system for persons transiting the jurisdiction’s

borders, either inbound or outbound, and carrying currency or monetary instruments