Family Planning and Medicaid Managed Care:

Improving Access and Quality Through

Integraon

Phase One Report

Sara Rosenbaum, JD

Peter Shin, PhD, MPH

Maria Casoni, MPH

Morgan Handley, JD

Rebecca Morris, MPP

Caitlin Murphy, MPA-PNP

Jessica Sharac, PhD, MSc, MPH

Akosua Tuoffer, JD

Devon Minnick, JD

In collaboration with Health Management Associates

June 2021

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

2

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the time we received from the state Medicaid agency leaders who

participated in this study, and the expertise and insights provided by our advisory committee,

whose members are listed in the Appendix. We deeply appreciate our colleagues at Health

Management Associates (Donna Checkett, Rebecca Kellenberg, and Carrie Rosensweig), who

collaborated with us throughout this study and continue to advise the project.

We are also so grateful to FAIR Health for providing us with healthcare claims data from the

private insurance market, which we used to analyze current practices among private insurers.

We are, of course, especially grateful to Arnold Ventures for its ongoing support.

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

3

State agencies, managed care plans, and public

health experts are increasingly focused on how

Medicaid managed care — a foundational part

of most state Medicaid programs — can

address whole-person health needs. Given its

documented impact on patient and population

health, high-quality family planning is essential

to a comprehensive managed care strategy.

For a half-century, family planning has been a

mandatory Medicaid service. Furthermore,

family planning has been deemed so essential

that since 1981, federal law has contained a

family planning out-of-network safeguard. This

safeguard guarantees that members of

Medicaid plans can continue to receive family

planning services from their Medicaid-qualified

provider of choice regardless of whether their

provider is part of their plan’s network.

At the same time, however, integration of family

planning and managed care is a desirable aim.

Good managed care practice means that

members should be able to look to their health

plans for comprehensive preventive care

delivered by a high-performing provider

network. Furthermore, family planning visits

uncover previously undisclosed physical and

mental health conditions requiring follow-up

care from other providers. This type of

integrated care approach presumably works

best when all providers and care managers

involved are members of the patient’s network.

This study was undertaken to understand the

current status of family planning and managed

care integration 40 years after enactment of the

“freedom of choice” safeguard, when managed

care now enrolls nearly 70 percent of the

Medicaid population. The study’s goal is to

identify practical, actionable opportunities for

greater integration and how managed care

purchasing might be used to strengthen family

planning while preserving the “freedom of

choice” safeguard.

This report shares findings from the first phase

of the study, which consisted of a review of

state purchasing documents related to

comprehensive managed care, and in-depth

interviews with senior Medicaid officials in 10

states. During Phase Two, we will conduct

similar in-depth interviews with managed care

plans and family planning providers.

Key findings include:

All states using comprehensive managed

care treat family planning as a fundamental

system feature. State officials emphasized

their expectations that contractors will fully

meet members’ family planning needs.

State purchasing documents codify the

“freedom of choice” safeguard to some

degree, but relatively few explicitly require

contractors to inform members regarding

the existence of their access safeguard.

No state viewed the “freedom of choice”

safeguard as imposing any real policy or

operational burden; indeed, nearly all

agreements address their obligation through

provisions requiring contractors to cover

and pay for family planning services

regardless of a provider’s network status.

States can do more to promote family

planning and managed care integration.

Areas of priority focus include: clarifying the

scope of family planning services to which

the “freedom of choice” safeguard should

apply, more detailed specifications

regarding contraceptive coverage, emphasis

on building strong family planning provider

networks to minimize reliance on out-of-

Execuve Summary

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

4

network care when possible, policies that

encourage contractor use of evidence-based

family planning practice guidelines to guide

network performance and value-based

payments that attract and reward strong

network providers, and ongoing work to

develop patient and population performance

measures.

More comprehensive federal guidance

regarding managed care and family planning

integration is of enormous importance, in

particular, guidance regarding the scope of

family planning services that should be

covered by “freedom of choice” safeguard —

including sexually transmitted infection (STI)

diagnostic and treatment services, HIV

assessment and counseling, and

immunizations to reduce cancer risk.

Classifying these services as part of the family

planning bundle for freedom of choice

purposes would promote greater consistency

between Medicaid and commercial sector

practices, where it is common and standard

for providers that offer basic family planning

services to provide, bill, and receive payment

for services such as STI treatment and testing.

Such a change in Medicaid managed care

practice would also help promote access to

treatment for STIs, which have reached public

health crisis proportions.

In addition to clarifying the scope of the

“freedom of choice” safeguard, the Centers

for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)

could spearhead efforts to develop best

practice approaches for family planning and

managed care integration, including service

coverage, network design, access

e n h a n c e m e nt , t e a m - b as e d c a r e

m a n a g e m e n t , a n d pe r f o r m a n c e

measurement and improvement. These

efforts can build on landmark Centers for

Disease Control (CDC) and HHS Office of

Population Affairs (OPA) family planning

standards of care by translating these

standards into managed care operational

terms. This comprehensive effort could be

carried out in collaboration with state

agencies, experts in managed care

performance and financing, clinical and

family planning practice experts, and experts

in public health and population-based health

improvement. Of great value would be the

inclusion of experts from the CDC and OPA,

who led the development of the family

planning practice standards. Such an effort

would come at a crucial time, as federal

agencies simultaneously move to restore the

nationwide Title X family planning network,

and whose providers play such a crucial

access role for the Medicaid population.

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

5

Introducon

This report presents initial findings and

recommendations from a two-phase study of

family planning and Medicaid managed care. The

purpose of the study is to identify strategies and

options for strengthening access to high-quality,

comprehensive family planning services as a core

Medicaid managed care service while at the same

time preserving key family planning direct access

safeguards that are a longstanding hallmark of

federal Medicaid policy.

Over the past 40 years, Medicaid managed care

has grown in scope and sophistication, and

enrollment in comprehensive managed care plans

now accounts for nearly 70 percent of all Medicaid

beneficiaries.

1

In the modern managed care era,

state purchasers, managed care plans, public

health and health management experts, providers,

and consumers are increasingly focused on putting

purchasing strategies to work to address the whole

-person health needs of plan members. Given the

profound relationship between overall physical

and mental health on one hand and reproductive

health on the other, family planning emerges as an

essential part of such a strategy.

Furthermore, in the U.S. — which has the highest

infant and maternal morality rates among wealthy

nations, and in which nearly half of all pregnancies

are unintended

2

— planned pregnancies become a

vital tool for ensuring that women enter and go

through pregnancy and the postpartum period in

optimal health. The argument for a greater focus

on high-quality family planning as an explicit,

integrated feature of Medicaid managed care is

also supported by research showing the large

proportion of patients in publicly funded family

planning settings — a patient group

disproportionately enrolled in Medicaid — whose

exams reveal previously unidentified physical and

mental health conditions requiring referral and

follow-up care.

3

For historic reasons explored further below, the

term “family planning” as used in Medicaid is a

broad one that has evolved over time to

encompass not only routine counseling, exams,

contraceptive services, and related follow-up care,

but also certain diagnostic and treatment

procedures aimed at preventing and treating

health conditions that can affect reproductive and

overall health. As a result, this report uses the

term “family planning” to encompass the full scope

of services as this scope has evolved under federal

law in response to public health and health care

expert recommendations.

4

Three major findings emerge from this initial study

phase.

First, states treat family planning as a

fundamental element of Medicaid managed

care and expect their health plans to fully meet

their members’ needs in this regard. In doing

so, states have absorbed Medicaid’s special

family planning “freedom of choice” access

safeguard into basic managed care operations

as a core feature of their purchasing systems.

Second, despite this embrace of family

planning as a basic feature of Medicaid

managed care, significant ambiguities emerge

in how states define and operationalize family

planning services in a managed care context.

These ambiguities begin with a lack of clarity

about what is covered by the “freedom of

choice” safeguard. Ambiguities also exist

concerning other key aspects of integrating

family planning into Medicaid managed care,

including strong network and access standards,

expectations regarding the level and quality of

family planning practice, quality improvement

and performance measurement, strategies for

follow-up care for family planning patients

with additional physical and mental health

conditions, and the use of value-based

payments to encourage a high-performing

network that can reduce reliance on out-of-

network care.

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

6

Third, the federal government similarly has a

critical opportunity to clarify and strengthen

the policy framework that guides the

integration of family planning, Medicaid

managed care, and states’ and plans’ efforts to

improve quality and accessibility. Of particular

importance is the need for greater clarity

regarding which family planning services

should be classified as family planning for

purposes of Medicaid’s special “freedom of

choice” safeguard, and guidance on strategies

to strengthen managed care performance

where family planning is concerned. An

initiative to strengthen the bonds between

managed care and family planning would

come at a crucial time, as the administration

works to restore the Title X family planning

program and the provider network on which

so many Medicaid beneficiaries depend.

A full study methodology, including all of the

tables that present the information presented in

this report in detailed form, can be found in the

Appendix, along with a list of advisors and the

states we interviewed.

Overview: Medicaid Managed Care

and Family Planning

The starting point for this initial project phase —

an in-depth examination of Medicaid managed

care purchasing agreements — reflects the

evolution of both Medicaid managed care and

family planning policy over the decades, virtually

from Medicaid’s enactment.

Medicaid managed care

The origins of what we know today as Medicaid

managed care date to the original 1965 law, which

authorized state agencies to purchase private

health insurance as a form of medical assistance

benefit.

5

Widespread adoption of managed care

began in earnest in the early 1980s with the

passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act

of 1981 (OBRA-81).

6

Over the ensuing decades, managed care became

the Medicaid program’s operational norm,

particularly for children and adults whose eligibility

is tied to low income alone. Enrollment grew

significantly in the 1990s as a result of a series of

federal Medicaid demonstrations carried out by

the Clinton administration under Section 1115 of

the Social Security Act. The Clinton

demonstrations initially coupled expanded

eligibility for low-income working-age adults (a

precursor to the 2010 ACA Medicaid expansion)

with compulsory enrollment into managed care

plans.

7

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 codified

mandatory Medicaid managed care as a state

option that eliminated the need for special

demonstration authority, with enrollment required

as a condition of eligibility for most beneficiaries.

8

Because of who enrolls in Medicaid — and

therefore, who is enrolled in Medicaid managed

care — any discussion of Medicaid managed care

policy also automatically becomes a discussion of

Medicaid and reproductive health policy. Seventy-

seven percent of women who are of reproductive

age and entitled to comprehensive Medicaid

coverage are also enrolled in Medicaid managed

care. This group includes women eligible under a

traditional eligibility category (very low-income

parents or caretakers of minor children, people

with disabilities, children and adolescents, and

women whose eligibility is tied to pregnancy). It

also includes women eligible as low-income adults

under the ACA Medicaid expansion.

9

(As discussed

below, certain Medicaid beneficiaries are entitled

only to limited family planning benefits and

services and generally are not enrolled in Medicaid

managed care).

The relevance of Medicaid managed care to

reproductive health is not limited to women, of

course. Millions of sexually active males — teens,

young adults, and, especially in Medicaid

expansion states, working-age men who are

fathers and sexual partners — depend on

Medicaid managed care for a full range of health

needs.

In many design and operational aspects, Medicaid

managed care parallels private health plans that

tie coverage to care through participating provider

networks. At the same time, Medicaid managed

care is distinct in the degree to which coverage is

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

7

restricted to in-network care. In a typical private

insurance plan, an insurer incentivizes in-network

care through lower patient cost-sharing and

protections against balance billing; members can, if

they choose, seek out-of-network care, with

coverage at a higher cost-sharing rate. But cost-

sharing financial incentives of any magnitude

cannot work for impoverished populations whose

access to care is so sensitive to more than nominal

cost-sharing.

10

For this reason, Medicaid managed

care systems utilize closed provider networks

subject to strict cost controls.

At the same time, federal law recognizes three

exceptions to Medicaid’s tightly controlled network

and coverage model:

Emergency care.

Like the Affordable Care Act

protections that govern the private insurance

and health plan markets,

11

federal Medicaid law

allows an exception for hospital emergency

care using a “prudent layperson standard.”

12

Services exempted from a state’s managed care

contract

. Most states either partially or wholly

exempt certain services from their managed

care purchasing agreements, especially benefits

related to high cost, high-need health care and

care furnished in settings that may not easily fit

within a managed care model, such as

homeless shelters or schools. Managed care

plans may, in some cases, help manage access

to these services and perform third-party

claims administration functions. However,

provider network restrictions would not apply,

and members would continue to have access to

any qualified Medicaid provider without regard

to network status. By law, managed care

organizations must inform members about

services covered under the state plan but are

not included in the service agreement.

12

“Freedom of choice” for family planning

services and supplies

. As part of OBRA-81,

Congress included a special family planning

exemption to normal managed care network

and access rules. The family planning

exemption covers “family planning services and

supplies” and guarantees that plan members

can continue to receive these services from

their Medicaid-qualified provider of choice,

regardless of network status. This special

exemption, required by federal law, reflects

both a Congressional desire to promote access

to care and to accommodate managed care

participation by religiously-affiliated health

plans whose contracts might limit or exclude

covered family planning services. The OBRA-81

“freedom of choice” guarantee, a key focus of

this study, is distinct from a separate protection

added to Medicaid in 1997, which guarantees

direct access to

in-network

women’s health

care providers without the need for a referral

from their primary care provider. This later

protection (discussed further below) would

subsequently be extended to insurance plans

more generally.

Medicaid family planning benets

Family planning has been a mandatory Medicaid

service for 50 years. In the context of this study,

two aspects of the benefit are notable.

First, under federal Medicaid law, the definition of

what constitutes “family planning services and

supplies” is quite broad. Under longstanding law

dating to the original 1972 family planning

amendments,

14

certain family planning services

(examinations and related tests, contraceptives,

and counseling) qualify for enhanced federal

funding at a 90 percent federal payment rate. But

the Affordable Care Act extended and broadened

the definition of family planning also to encompass

“medical diagnosis and treatment services that are

provided pursuant to a family planning service in a

family planning setting.”

15

In implementing this expanded definition of family

planning, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services (CMS) has elected to divide the benefit

into two clusters: family planning services and

“family planning-related services.” Under CMS

guidelines, “family planning services” qualify for 90

percent federal funding, while “related” services are

paid at the regular federal medical assistance rate

(between 50 percent and 77 percent in 2021). Both

types of benefits can be covered for people

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

8

entitled to limited Medicaid benefits for family

planning under the ACA’s special Medicaid family

planning eligibility option. As of 2021, 26 states

provide coverage for this limited benefit group.

16

Second, in the case of beneficiaries entitled to full

Medicaid benefits, the definition of family planning

benefits also can vary. For the traditional

population entitled to Medicaid prior to the ACA,

the required scope of family planning benefits

includes contraceptives whose scope would be

governed by Medicaid’s basic test of coverage

reasonableness.

17

For the ACA adult expansion

group, however, contraceptive coverage explicitly

includes all FDA-approved contraceptive

methods.

18

Furthermore, the ACA Medicaid

expansion group is entitled to “essential health

benefits” under “alternative benefit plans.” The

essential health benefit standard also explicitly

includes a bundle of services classified as “women’s

preventive health services” that includes both

benefits considered to be family planning services

and supplies as well as other benefits such as

screening for interpersonal and domestic violence,

preventive exams, and diabetes screening, as

shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 2 shows the three basic Medicaid eligibility

pathways and how family planning benefits can

vary by pathway depending on how states

implement the family planning coverage

requirement.

Regardless of the basis of eligibility, however, it is

important to stress that the federal definition of

family planning is potentially very broad. CMS

provides guidance on which family planning

benefits qualify for 90 percent federal funding and

which are “related” and qualify for federal

payments at the regular FMAP rate and are

potentially available to the limited family planning

eligibility group. But the guidance is silent on

which family planning benefits are covered by

Medicaid’s “freedom of choice” safeguard. The

assumption appears that the safeguard extends to

those benefits recognized as such in 1981

(counseling, contraceptives, exams). The guidance

does not consider the interaction between the

“freedom of choice” safeguard and the subsequent

2010 amendment that fundamentally altered the

Figure 1. Women’s Preventive Health Services

Source: Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

Screening for anxiety

Breastfeeding services and supplies

Cervical cancer screening

Screening for cervical cancer

Contraception care including counseling, initiation of contraceptive use,

counseling (all FDA-approved contraceptive methods)

Screening for diabetes both during and after pregnancy

Screening for HIV

Screening for interpersonal and domestic violence

Counseling for sexually transmitted infections

Well women preventive visits

Screening for urinary incontinence

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

9

definition of family planning services.

Medicaid care and family planning

integraon

The breadth of family planning services and

supplies are foundational to preventive care and

can act as a key entry point into health care more

generally. This underscores the value and

desirability of integrating family planning into

comprehensive managed care systems as part of a

“whole person” health strategy improvement

strategy. A strong orientation toward integration

would emphasize a wide choice of family planning

network providers and a comprehensive range of

family planning services to encourage early

detection of conditions affecting overall

reproductive health. Inclusiveness also would

emphasize performance standards that include

special accessibility efforts reaching all qualified

providers in medically underserved communities,

Figure 2. Principal Medicaid Eligibility Pathways and Family Planning Coverage Variaon

Eligibility Pathways Family Planning Coverage

“Traditional” beneficiaries:

Low-income children

Very poor parents and caretaker

relatives

Children and adults with disabilities

Pregnant/postpartum women

Family planning services and supplies. Federal guidelines that

identify which services qualify for 90 percent federal funding

define the term as consisting of counseling services and

patient education; examination and treatment; laboratory

examinations and tests; medically approved methods,

procedures, and devices to prevent conception; and certain

infertility services. Medically necessary diagnosis and

treatment services for conditions found in a family planning

visit typically would be covered under the state plan rather

than as a family planning service.

ACA expansion beneficiaries:

Low-income, non-elderly adults with

household incomes up to 138% FPL

All essential health benefits, including all FDA-approved

contraceptive methods, as well as a broad package of

women’s preventive health services — which may extend be-

yond the Medicaid definition of family planning and related

services both in scope and the range of services furnished in a

family planning setting (e.g., screening for anxiety and

depression).

Beneficiaries eligible for family

planning and family planning-related

coverage:

Incomes between 138% FPL and

states’ upper-income limit for

pregnant women

Family planning services and supplies — defined as including

not only contraceptives, tests, and counseling, but medically

necessary diagnosis and treatment for conditions disclosed

during a family planning visit and furnished in a family

planning setting.

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

10

especially those that offer special programs for

hard-to-reach populations such as immigrants,

adolescents, or patients with disabilities or

underlying behavioral health conditions. In other

words, effectively integrating family planning into

Medicaid managed care raises a host of important

considerations when designing effective systems

for a diverse and vulnerable population that go

beyond simply covering and paying for family

planning services but orienting managed care

systems to reach members with complex needs,

and to focus special attention on issues such as

confidentiality and patient supports. Integration

also means incorporating evidence-based practice

standards as a network expectation, adopting value

-based payment strategies to attract and retain a

high-performing network, and developing

performance measures that can capture certain

outcomes, as well as evidence of basic procedures

such as cervical cancer screening for adults

19

and

chlamydia screening for adolescent women ages

16-20.

20

Models of managed care/family planning

integration.

The complexity of integration means

that managed care and family planning integration

can be thought of as happening along a spectrum,

from limited integration to comprehensive

integration and prioritization. Under limited

integration that mainly relies on the “freedom of

choice” safeguard to promote access to care,

family planning might be covered. Still, only a

modest focus would be given to aspects of

managed care such as networks, access,

performance standards, payment incentives, links

between family planning network providers and

social services, and quality measurement and

performance improvement. Plans essentially would

emphasize their role as claims managers, and

members would seek care from their provider of

choice. Family planning would exist as a covered

Limited Comprehensive

Family planning benefits are covered but

broadly defined

Services covered by the “freedom of choice”

exemptions are not defined

Contract does not specify family planning-

focused access or network specifications

Contract does not specify specific expectations

regarding referrals between out-of-network

family planning providers and in-network care

Contract does not incorporate social

determinants expectations specifically into

family planning services

Contract does not specify family planning-

related performance expectations or quality

improvement goals

Family planning is specified in detail with

coverage spanning the full range of federally-

permissible services

Services covered by the “freedom of choice”

exemption are defined

Contract specifies detailed access and network

expectations

Contract specifies referral arrangements for

follow-up care

Contract specifies a focus on family planning

patients with social determinants needs

Contract specifies family planning performance

expectations and quality improvement goals

Figure 3. Models of Family Planning/Managed Care Integraon

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

11

benefit but not one subject to robust coverage,

access, or performance specifications.

In a more robust integration model, the contract

would lay out more detailed specifications

governing coverage and performance to elevate

the importance of family planning access, quality,

and performance as a major focus of managed

care patient and population health improvement.

The contract would be more specific regarding

networks, coverage, performance expectation,

referral systems, linkages between family planning

and social services, and other matters. Payment

incentives would be in place for plans and provider

networks that achieve high performance as defined

by evidence-based practice standards, such as

providing same-day walk-in care, the “quick start”

family planning method, and other strategies

designed to make family planning simple and easy

to access.

The basic features of what might be thought of as

two distinct models for approaching managed care

and family planning are shown above in Figure 3.

Study Aims and Assumpons

This two-phase study has been designed to better

understand the issues in family planning and

Medicaid managed care integration and how states

currently approach these issues. The first study

phase, whose results are presented here, offers a

baseline assessment of issues and state

approaches through an in-depth review of

managed care purchasing agreements coupled

with in-depth discussions with state Medicaid

leaders.

As with our previous work in the field of managed

care policy and practice, we assume that there is

no correct answer to the question of “how much”

or “to what extent” to integrate managed care and

family planning — and how robustly and with what

level of focus. On-the-ground health care

conditions, public health, and policy priorities,

consumer preferences, other considerations

strongly influence how states shape and design

their managed care systems and the priorities they

choose.

At the same time, we also believe that much is to

be gained from a focus on greater managed care

and family planning integration in terms of quality,

efficiency, and the promotion of reproductive and

overall patient and population health.

Furthermore, because real-world considerations

play such an important role in Medicaid managed

care design and operationalization, the 1981

“freedom of choice” exemption remains as

important today as it was when it was originally

enacted, since the exemption assures that states

and health plans can adjust their activities and

areas of emphasis without compromising access to

this essential benefit.

Finally, we assume that because an understanding

of, and experience with, both family planning

practice and the field of Medicaid managed care

has changed dramatically over the past four

decades; we believe that a deep dive into the

family planning/managed care integration

question will add value to health care practice and

policy.

Study Overview

This study phase presents findings from our

baseline study, which involved a detailed analysis

of state Medicaid managed care purchasing

agreements coupled with discussions with senior

Medicaid officials in ten states. This baseline is

intended to help illuminate what can be thought of

as the managed care “blueprint” in all states: the

major purchasing agreements on which all

Medicaid managed care systems sit.

21

Medicaid managed care contracting is challenging

for an impoverished, high-need population

because the act of purchasing goes far beyond the

concerns involved in purchasing typical private

health plans. In light of the concentration of

Medicaid beneficiaries with complex needs in poor

rural and urban communities with extensive

medical underservice problems, network

sufficiency and capability considerations rise to the

forefront, as do access concerns. Coverage must be

well-defined to capture the full range of covered

services included in the contract. Utilization

management approaches must be tailored to a

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

12

member population with elevated health and social

needs. Relationships with social service and other

providers must be in place. Quality improvement

priorities must be tailored to a member population

with complex needs. Federal managed care

requirements must be satisfied along with state

laws governing large-scale procurements.

Thus, managed care can vary enormously from

state to state depending on population need, on-

the-ground health care conditions, legal

considerations, policy priorities among state

lawmakers, advocates, and health professionals,

procurement laws, and the customs and practices

of the managed care industry itself. Along with

this variation in approaches to Medicaid managed

care comes variation in state purchasing

agreements. Some states may broadly word their

agreements and supplement general agreements

with more detailed guidance documents, while

other states might take a granular approach to

their agreements, filling them with detail. Some

states may use a procurement approach that

begins with a procurement announcement and

then incorporates acceptance of plan responses to

a standard set of terms and conditions, meaning

that the contractor’s response guides the detail.

Despite these differences, federal law treats

Medicaid contracts as the foundation of state

systems, and our studies of Medicaid managed

care contracts over nearly three decades

underscore the degree to which all states use

purchasing agreements to signal areas of high-

priority interest and focus. A state’s priorities might

result from the on-the-ground public health

conditions or health care realities (particularly, the

concentration of Medicaid beneficiaries in low-

income urban and rural communities at risk for

health and social risks coupled with a shortage of

primary care services). State priorities might also

reflect gubernatorial or legislative initiatives.

Moreover, because the purchase of health care is

so complex, any managed care contract is a mix of

the specific and the general. That is, in any state,

the contract will reflect areas of high specificity

where a state desires a specific approach or a

specific result, and the other issues are left

substantially to contractor discretion in accordance

with prevailing industry practice.

In sum, despite certain limitations, Medicaid

managed care purchasing documents play a

central role in state systems and offer a means of

gaining an overall picture of states’ health system

approaches and priorities.

Appendix 2 provides a fuller explanation of our

methods. In brief, this study involved collecting

public purchasing documents from the 39 states

and the District of Columbia in which

comprehensive managed care was in use in 2020.

These documents were reviewed using an

instrument designed to capture each document’s

framework in detail through a series of six

domains, each with numerous sub-topics (shown in

Figure 4). Each domain and sub-topic are relevant

in assessing the extent to which state purchasing

agreements contain express specifications aimed at

translating family planning practice and policy for

medically underserved populations into their

managed care purchasing blueprints. In developing

these domains and sub-topics, we were guided by

comprehensive family planning guidelines

developed by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Population

Affairs (OPA), federal Medicaid policy

considerations, and project advisors (listed in

Appendix 3) whose expertise spans Medicaid

policy, family planning policy and practice,

managed care, and primary care practice and

policy.

Once the domains and sub-topics were finalized

and converted into a review instrument, a team

trained and experienced in analyzing Medicaid

managed care purchasing documents reviewed all

state agreements and prepared the detailed

master tables found in Appendix 1. These tables

provide two levels of information: 1) an overview of

the degree to which documents do or do not

contain family planning-specific provisions

addressing a particular domain or subtopic; and 2)

the actual language contained in each state

document relevant to that domain or subtopic,

which gives users the ability to compare precisely

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

13

Figure 4. Managed Care and Family Planning: Study Domains and Sub-Topics

Domain 1. Coverage

Identifies family planning as a covered benefit

Coverage is explicit on coverage of all FDA-approved family planning methods

Coverage of family planning services and supplies is coextensive with the coverage provided by the state Medicaid

plan

Coverage of family planning as a postpartum benefit is required

Family planning-related services are defined

Quick start contraception

1

is required as a contract service

Domain 2. Access and Provider Networks

Coverage of out-of-network family planning services regardless of network status

Coverage of family planning-related services regardless of network status and without prior authorization

Network contracts offered to all Medicaid-qualified family planning providers in the plan service area

Bars against the use of prior authorization or other utilization management methods for family planning services

Incentives for same day walk-in care

Maximum wait times for family planning visits

Maximum travel time for family planning visits

Family planning provider/patient ratios

Telehealth family planning visits

Non-emergency transportation for family planning

Domain 3. Information for Plan Members

Contractors required to inform members of free choice of family planning providers

Contractors required to inform female members of their right to direct access to in-network women’s health

specialists without prior authorization

Contractors required to inform members of any family planning services covered under the state plan but not

include in the contract

Contractors required to inform members about relevant family planning confidentiality considerations

Contractors barred from disclosing family planning visit information in members explanation of benefits

Domain 4. Payment Incentives

Requirement for payment add-on or incentives for family planning drugs and devices furnished incident to a family

planning visit

Separate payment for postpartum long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs; i.e., IUDs, contraceptive implants)

Value-based payments for family planning services

Domain 5. Social Determinants of Health

Family planning patients identified as a prioritized population for social risk health screening

Referral arrangements required between family planning providers and social service agencies

Domain 6. Quality Improvement and Performance Measurement

Family planning and family planning-related-specific performance measures

Family planning performance measures as part of maternity care

Specifies one or more family planning health outcome measures

Adolescent performance measures for family planning specified

1

“Quick starting” is a the term used to describe immediate initiation of a contraceptive method at the time a woman requests it, rather than waiting for

the start of the next natural menstrual period.

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

14

how different states may address a topic. In the

context of purchasing agreements, these details

matter in framing the scope of state expectations

and the degree of discretion afforded to plan

contractors.

Findings

Our review of state Medicaid plans — the

foundation on which managed care contracts rest

— results in two key findings.

First, our review suggests that in contracting for

managed care, while all states view family planning

as a foundational service, states tend not to elevate

family planning as a major area of focus in terms of

coverage and performance specificity. Indeed,

contract documents tend to leave plans with broad

discretion to define the full scope of what

constitutes family planning coverage itself,

including the types of coverage that should be

covered by the “freedom of choice” exemption. Of

course, there are notable exceptions, but overall,

family planning is a basic expectation but not one

that merits extensive specification or emphasis as a

performance priority.

Second, while the selection of key areas of focus is

principally a matter of state leadership and choices,

the federal government’s silence on managed care

and family planning is also quite notable. For

example, the federal government has been a leader

in the development and publication of landmark

guidelines on high-quality family planning services.

CMS has launched an effort to develop more

robust measures of managed care family planning

performance. But in other critical respects, CMS

activities have been limited. For example, CMS has

never developed detailed guidance on how states

might translate the CDC/OPA guidelines into a

managed care operating environment. Nor does

CMS maintain guidelines regarding the range of

considerations that go into Medicaid managed

care and family planning integration or how to

align managed care coverage and performance

with the “freedom of choice” exemption.

Indeed, even basic CMS documents — such as the

preprinted document states use to describe their

state plan coverage — are ambiguous and unclear.

As a result, it is not possible from the preprints to

know the full scope of state coverage of family

planning, including which benefits and services

identified in federal law are classified as a family

planning benefit and which benefits are covered by

the “freedom of choice exemption.”

22

Two states

plans specify unequivocally (Ohio and New Jersey)

that as a basic state plan matter, all comprehensive

coverage beneficiaries are entitled to all FDA-

approved contraceptive methods regardless of

their basis of eligibility. Other state plans are

ambiguous, and this ambiguity carries through to

the purchasing itself.

In sum, an important consideration in most states’

decisions to elevate family planning as a focus of

managed care priority may be that except for an

effort to develop more refined quality measures,

managed care and family planning are not a focus

for CMS either.

Summary ndings from the Medicaid

managed care contract review

Figures 5 through 10 present summary findings

from our contract review of public purchasing

documents from the 39 states and the District of

Columbia utilizing comprehensive managed care in

2020. The tables referred to in each of these

figures can be found in Appendix 1.

Coverage

As Figure 5 shows, family planning is a basic

offering of all state managed care agreements. In

other words, no states, in response to the “freedom

of choice” guarantee, has elected to simply exempt

family planning services and supplies from its

managed care system. States assume (confirmed

by our discussions with state officials) that family

planning is a basic feature of their managed care

systems. Eight states explicitly include language on

coverage of all FDA-approved family planning

methods. Figure 5 also shows that 12 state

agreements specify that contractor coverage of

family planning services must be coextensive with

the state plan, presumably eliminating contractor

discretion to define coverage scope.

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

15

Nine states specify family planning as a pregnancy-

related postpartum service. No states specify what

is meant by coverage of family planning-related

services. No states specify coverage of quick-start

contraception, which permits coverage in the

absence of an initial exam.

Access to coverage and provider networks

Figure 6A shows that 18 states specify that

contractors must pay for all family planning

services when furnished by a qualified Medicaid

provider, regardless of the provider’s network

status. Twenty-six states bar use of prior

authorization or other utilization management

techniques in the case of family planning services.

Figure 6A also shows that although states do not

specify what constitutes family planning-related

services in a coverage context, four states specify

that contractors must pay for family planning-

related services when furnished by a Medicaid

provider, regardless of network status and without

prior authorization. Six states specify that

contractors must offer network contracts to all

qualified Medicaid providers in their plan service

area.

Figure 6B reports on family planning-specific

versions of general access measures such as travel

times, wait times, and provider/patient ratios. With

respect to rapid access, six states require or specify

incentives to create same-day walk-in access. Six

states reference maximum wait times for in-

network family planning services, 19 reference

travel times, four reference provider/patient ratios,

six specify the use of telehealth services, and 31

states specify non-emergency transportation for

family planning visits.

Information for plan members

As seen in Figure 7, 11 states specify that

contractors must inform members of their right to

family planning services from the qualified provider

of their choice and without regard to network

status or prior authorization. Fifteen states

expressly require that contractors inform members

of their right to directly access any in-network

women’s health specialist for routine preventive

care, a specific information guarantee under

federal law.

Fourteen states require plans to inform members

regarding the full scope of family planning

coverage under the state plan (which may differ

from what the contractor offers) and where and

how to obtain services not covered under the

contract. Among these 14 states, five states

specifically stipulate that enrollees must be

informed about how to access covered services

that the contractor has objected to on moral or

religious grounds. However, no contract appeared

to require contractors to identify religiously

affiliated providers within their network.

No states specifies that contractors are required to

inform members about their rights regarding

family planning and provider-patient

confidentiality. One state bars contractors from

including identifiable information about a family

planning visit in the explanation of benefits (EOB)

sent to members.

Payment and payment incentives

As Figure 8 shows, one state specifies additional

payment to providers for drugs and devices

furnished during an office-based family planning

visit. In contrast, two states require contractors to

make separate payments for hospital-inserted

LARCs. Five states encourage the use of value-

based payment models for either office-based or

hospital-based family planning services.

Social determinants of health

Figure 9 reports that no state identifies family

planning patients as a specific priority population

for social and health risk screening, while one state

requires contractors to maintain referral

relationships between their in-network providers

and social service agencies.

Quality improvement and performance

measurement

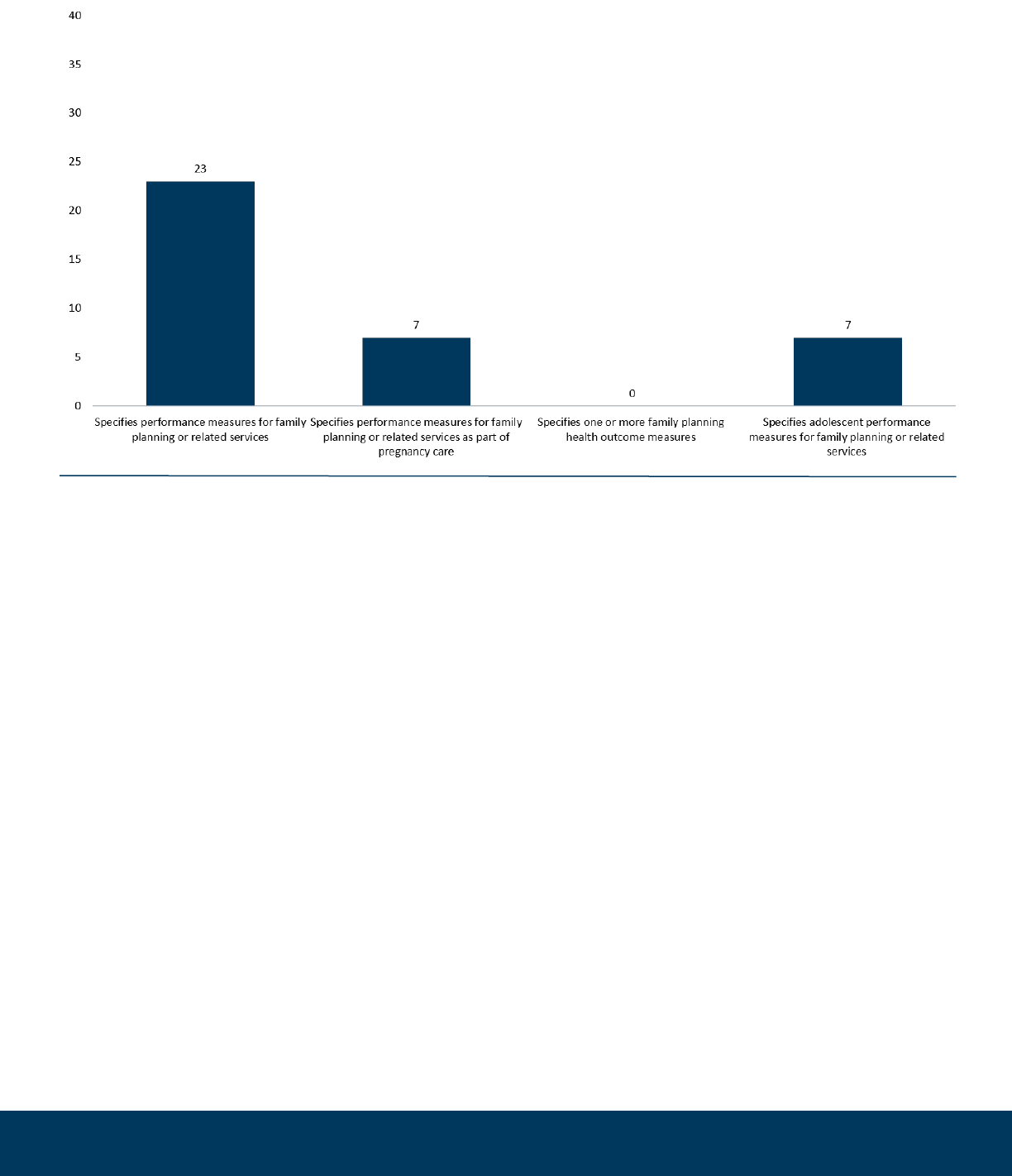

Last, Figure 10 shows that 23 states specify

performance measures for family planning or

family planning-related services. In many cases,

state measures focus on family planning-related

services, such as cervical cancer screening or

chlamydia screening. Seven states specify family

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

16

planning as a pregnancy-related performance

measure, and seven states specify family planning

performance as a measure of adolescent health.

No states specifies a family planning health

outcome measure.

State variaon in contract terms: a closer

look

These summary findings provide a high-level

overview of the extent to which state purchasing

documents, as a group, contain coverage, access,

network, quality, payment, and performance

provisions specific to family planning. But within

these high-level patterns, important differences

can be seen in the precise approach that any two

or more states might take to the same topic or

focus area. As we have noted in our previous

Medicaid managed care research,

23

empirical

evidence does not exist that would suggest that

one approach to drafting achieves better

outcomes; contracts that vest plans with discretion

as to whether to cover and furnish certain services

and, if so, to what extent, may achieve results that

do not differ from contracting approaches that are

more directive.

But for standard setting and accountability

reasons, states and plans typically agree to specific

performance expectations regarding coverage,

care, payment, quality improvement, consumer

safeguards, and other matters. Indeed, one of the

most important decisions states and plans make is

how to balance deference against clarity. Many

considerations may enter into this equation, such

as whether on-the-ground conditions make the

realization of the standard feasible, and

considerations of cost and efficiency. For this

reason, this variation in coverage and deference is

a signature characteristic of state contracting

practices around any particular topic. For example,

a specification that defines contractor coverage

obligations as “appropriate family planning

services” would signal to contractors the flexibility

to set parameters on coverage that may differ from

all FDA-approved contraceptive methods or even

the level of coverage afforded by the underlying

state Medicaid plan.

Silence on a particular matter signals a policy

judgment in its own right. For example, a contract

may be silent on the use of telehealth services. This

does not mean that telehealth services might not

be available under plans’ operating standards, but

instead that whether to use telehealth services and

under which conditions is left to contractor

discretion.

Drawing from the tables in Appendix 1, we offer

several comparisons to illustrate this basic point

about how contracts are drafted.

I. Coverage of Family Planning Services

As discussed, federal law gives states considerable

discretion to define the term “family planning

services and supplies.” A state’s definition would

be relevant not only as an expression of the state’s

policy regarding what a high-quality family

planning service should encompass but also

because the definition would play a key role in

defining the scope of the state’s “freedom of

choice guarantee.”

Nevada uses a succinct definition:

Vendor Covered Services … At a minimum, the

Vendor must provide directly, or by subcontract, all

covered medically necessary services, which shall

include, but may not be limited to, the following:

4.2.2.13 Family Planning Services.

South Carolina uses a more extensive definition:

4.2.12. Family Planning Services—Family Planning

Services include traditional contraceptive drugs,

supplies, and preventive contraceptive methods.

These include, but are not limited to the following:

(1) examinations, (2) assessments, (3) diagnostic

procedures, and (4) health education, prevention

and counseling services related to alternative birth

control and prevention as prescribed and rendered

by various Providers.

Under both state definitions, contractors

presumably would have the latitude to determine

when certain services are furnished in a family

planning setting and pursuant to a family planning

visit (such as the HPV vaccine or diagnosis).

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

17

Figure 5. Summary Findings from Table 1: Coverage

Figure 6A. Summary Findings from Table 2: Access to Coverage and Provider Networks

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

18

Figure 6B. Summary Findings: Access to Coverage and Provider Networks

Figure 7. Summary Findings from Table 3: Informaon for Plan Members

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

19

Figure 8. Summary Findings from Table 4: Payment Incenves

Figure 9. Summary Findings from Table 5: Social Determinants of Health

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

20

Arizona’s contract defines the postpartum family

planning duty as follows:

The Contractor must monitor rates and implement

interventions to improve or sustain rates for low/

very low birth weight deliveries, utilization of long

acting reversible contraceptives (LARC), prenatal

and postpartum visit.

Louisiana defines the postpartum coverage

obligation as follows:

The MCO shall provide pregnancy-related services

that are necessary for the health of the pregnant

woman and fetus, or that have become necessary

as a result of being pregnant and includes but is

not limited to prenatal care, delivery, postpartum

care, and family planning services for pregnant

women.

Arizona’s contract is drafted in a way that

approaches postpartum family planning as an

intervention that arises out of patient monitoring

post-delivery, with the intervention seemingly

required if monitoring suggests the need for such

an intervention. Louisiana, by contrast, specifies

family planning as part of the pregnancy bundle,

not conditioned on the results of member or

patient monitoring. Arizona’s drafting would

support contractor accountability in terms of

provision of the intervention in the wake of

evidence, as defined by the contractor, that is

gained from monitoring. Louisiana sets a

performance expectation of family planning as a

basic element of postpartum coverage.

II. Access to Family Planning-Related Services

from Out-of-Network Providers

Although the contracts lack specific coverage

terms regarding what must be covered out-of-

network, four states set standards in terms of

access. California addresses the issue of out-of-

network coverage in some depth, while

Pennsylvania offers a general minimum and thus

would rely on contractor discretion.

California’s contract providers as follows:

Out of network family planning services. Members

of childbearing age may access the following

services from out-of-network family planning

providers to temporarily or permanently delay

pregnancy: (a) health education and counseling. . . ;

Figure 10: Summary Findings from Table 6: Quality Improvement & Performance

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

21

b) limited history and physical examination. . . . c)

laboratory tests if medically indicated. Contractor

shall not be required to use out of network

provider for pap smears if contractor has provided

pap smears to meet U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force guidelines . . . . d) diagnosis and treatment of

a sexually transmitted disease episode . . . . e)

screening testing and counseling of at risk

individuals for HIV and referral for treatment. . . . f)

follow-up care for complications associated with

contraceptive methods. . . . g) provision of

contraceptive pills, devices and supplies . . . . h)

tubal ligation. . . . i) vasectomies; j) pregnancy

testing and counseling.

Compare this language with an excerpt from

Pennsylvania:

The PHO-MCO may not use either the referral

process or Prior Authorization to manage the

utilization of family planning services. . . . Members

may access at a minimum, health education and

counseling. . . ., pregnancy testing and counseling,

breast cancer screening services, basic

contraceptive supplies such as oral birth control

pills, diaphragms, foams, creams, jellies, condoms

(male and female), Norplant, injectables,

intrauterine devices, and other family planning

procedures.

[Bold emphasis added.]

Whereas California presents contractors with a

defined list, Pennsylvania gives contractors the

discretion to add to the minimum list or elect to

not do so.

III. Performance Measurement

Performance measures are not without

controversy; nevertheless, the development of

more robust family planning performance

measures has been a recent focus within CMS. As

of 2018, four contraceptive measures were

available in the CMS Maternal and Perinatal Health

Measures Core Set for voluntary reporting by state

Medicaid agencies. These measures include 1)

Contraceptive Care among Postpartum Women

Ages 15 to 20, 2) Contraceptive Care among

Postpartum Women Ages 21 to 44, 3)

Contraceptive Care among All Women Ages 15 to

20, and 4) Contraceptive Care among All Women

Ages 21 to 44.

24

This set seeks to measure the

percent of women at risk of unintended pregnancy

who were provided with a “most effective or

moderately effective” FDA-approved method of

contraception, such as LARCs.

25

Seven states currently include at least one of these

CMS contraceptive core measures in their Medicaid

managed care contracts: Arizona, Florida, New

Jersey, Louisiana, New Mexico, and Oklahoma.

Louisiana, for example, has included the two CMS

Contraceptive Care among Postpartum Women

core measures — making the state one that

establishes a clear link between a specific

expectation of postpartum family planning

coverage and a specific measure of performance:

Contraceptive Care-Postpartum (ages 15-20)

Measure Description: The percentage of women

ages 15-20 who had a live birth and were provided

a most or moderately effective method of

contraception within 3 and 60 days of delivery.

Four rates are reported. Contraceptive Care-

Postpartum (ages 21-44) Measure Description: The

percentage of women ages 21-44 who had a live

birth and were provided a most or moderately

effective method of contraception within 3 and 60

days of delivery. Four rates are reported.

A few states included contraceptive measures

which were distinct from the CMS contraceptive

core set. For example, Georgia has attempted to

capture the outcomes of its Planning 4 Healthy

Babies Program, a special demonstration

embedded in its managed care system:

Planning 4 Healthy Babies Program Objectives […]

Improve access to family planning services by

extending eligibility for family planning services to

all women aged 18 – 44 years who are at or below

200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) during the

three year term of the Demonstration.

Achievement of this objective will be measured by:

Total family planning visits pre and post the

Demonstration; Use of contraceptive services/

supplies pre and post the Demonstration; Provide

access to inter-pregnancy primary care health

services for eligible women who have previously

delivered a very low birth weight infant.

Achievement of this objective will be measured by:

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

22

Use of inter-pregnancy care services (primary care

and Resource Mothers Outreach) by women with a

very low birth weight delivery; Decrease

unintended and high-risk pregnancies among

Medicaid eligible women and increase child

spacing intervals through effective contraceptive

use to foster reduced low birth weight rates and

improved health status of women. Achievement of

this objective will be measured by: Average inter-

pregnancy intervals for women pre and post the

Demonstration; Average inter-pregnancy intervals

for women with a very low birth weight delivery

pre and post the Demonstration; Decrease in late

teen pregnancies by reducing the number of

repeat teen births among Medicaid eligible

women. Achievement of this objective will be

documented by: The number of repeat teen births

assessed annually; Decrease the number of

Medicaid-paid deliveries beginning in the second

year of the Demonstration, thereby reducing

annual pregnancy-related expenditures.

Achievement of this objective will be measured by:

The number of Medicaid paid deliveries assessed

annually; Increase consistent use of contraceptive

methods by incorporating Care Coordination and

patient-directed counseling into family planning

visits. Achievement of this objective will be

measured by: Utilization statistics for family

planning methods or Number of Deliveries to

P4HB participants.

Discussions with state Medicaid ocials

Upon completion of our contract review, we held a

series of 10 discussions with senior Medicaid

officials to learn more about their thinking

regarding the relationship between Medicaid

managed care and family planning generally and

their approaches to family planning through

managed care purchasing. See Appendix 4 for a

full list of the 10 states with whom discussions

were held. (Note: Interviews with plans and

providers will take place during Phase 2 of this

study.) From these discussions, several key themes

emerged:

Family planning is part of the “routine operation,”

“basic general care,” and “integrated care” that

managed care plans are expected to provide.

All

discussants viewed family planning as part of their

state’s core Medicaid managed care operation, not

one that stands apart. While the “freedom of

choice” provision stands as a key access safeguard,

the existence of this provision did not cause

agencies to either think about or treat family

planning as somehow separate from their overall

health care purchasing strategy. Indeed, officials in

one state view the safeguard as the basis for a

requirement that their contractors not only pay

providers for out-of-network care but have

working two-way referral arrangements with all

Medicaid participating family planning programs in

their service areas. In other words, the presence of

out-of-network coverage protection is in and of

itself the basis for an operational expectation.

In states that have prioritized family planning as a

service to receive a higher level of attention, this

prioritization can be traced to individual leadership.

All agencies recognize the importance of family

planning as a matter of both patient and

population health. The decision to elevate family

planning contractually — through greater clarity

and specificity of expectations — is the result,

officials say, of deliberate leadership decisions by

agency officials, public health officials, and other

state leaders concerned about both individual and

population health and its link to the timing and

spacing of pregnancy. In one state, this decision to

move more aggressively on family planning came

from the realization that the state’s unintended

pregnancy rates were too high. Another state

decided to make performance improvement in its

hospitals (in the case of postpartum family

planning) and community health centers a policy

and strategic planning priority and intends to use

its comprehensive health system reform

demonstration renewal as a tool for focusing on

this issue. Other states indicated that the focus on

family planning was part of a broader initiative —

for example, an effort to make well-woman’s health

care a major priority in Medicaid managed care or

to bring a family planning focus into initiatives

around pregnancy care.

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

23

Agencies view family planning and the “freedom of

choice” exemption as an issue that has been

operationalized with relative ease

. All Medicaid

agencies, health plans, and providers face

challenges in operationalizing aspects of health

system delivery reform. The agency officials we

spoke with viewed family planning operations as

smooth and with few hiccups. Those officials who

were familiar with problems noted that they were

manageable (e.g., payment rate adjustments,

additional payment for postpartum LARC

unbundled from the hospital delivery rate, ensuring

that MCOs fully understand and embrace family

planning as a focus of state interest, limited

member take-up of certain types of long-acting

contraceptives). From the agencies’ perspective,

issues in family planning are considered readily

identifiable, and their resolution has clear answers.

Whatever problems arise are ones that can be

addressed. Although contracts may not specify

coverage of all family planning methods, no state

has heard from providers that a method is being

denied coverage.

Agencies struggle with which issues to prioritize

and when to translate priorities into clear

contractual expectations.

All agencies focused to a

greater or lesser degree on the tension between

the scope of the undertaking they face (that is,

buying health care for entire populations), when to

make a particular population or service a major

priority, and when to set clear expectations that

effectively are intended to move all contractors in

the same direction on a matter of overarching

importance. In other words, the question of when

to set general directions and allow contractors to

exercise judgment and innovation, and when to

choose a strategy or a standard and expect

uniform adaptation, is one of the most difficult

questions that agencies confront — whether in the

area of primary and preventive care or care for

complex health conditions. Indeed, as one agency

told us, the point of managed care is to get the

benefit of contractor expertise and the flexibility

that comes with capitation and allows contractors

to test approaches that are not possible in a fee-

for-service context. This uncertainty over when to

add or strengthen priorities also carries over into

decisions about updating and adding performance

expectations. Contracts are often for multi-year

terms, and states may frequently update or alter

terms and payment structures. In other words,

whether to modify expectations or requirements

for contractors does not arise only when new

contracts are established but is a continuous

matter.

Agencies are varied on the issue of networks.

The

in-network/out-of-network dichotomy appears to

play out differently for different states. Some

reported a deliberate strategy aimed at enlarging

their managed care family planning networks as a

means of bolstering the role of their health plans

as comprehensive systems of care and ensuring

network adequacy. Other states did not perceive

networks as an issue, expressing the sense that the

“freedom of choice” provision eases this concern

and effectively allows both providers and member

to make their own decisions. This view was perhaps

best expressed by one state official who indicated

the sense that “most state family planning

providers have in-network contracts with at least

one plan.” Still, for the agencies, the issue of in-

network or out-of-network did not raise concerns.

While states indicated their desire that plans make

a reasonable effort to enroll family planning

providers, it was evident in the discussions that

ensuring in-network access did not register as a

matter of urgency. Thus, there was no pressure in

their view to “dictate” network design to their

plans, as one agency official put it.

States are relatively split on their plans as claims

administrators for out-of-network providers.

Some

use plans as claims administrators for all family

planning services regardless of network status,

while others do not. Those who do not use plans as

claims administrators noted minimal problems, and

if problems did arise (e.g., confusion over the

payer), they were resolved with relative ease.

However, one state was concerned that requiring

family planning providers to bill multiple plans may

be placing too much of a burden on them.

States are split on the use of some level of

utilization management for family planning

services.

Several states prohibit pre-approval or

The George Washington University Milken Instute School of Public Health

24

other forms of utilization management, while

others do not. Those whose contracts do not bar

utilization management varied in their approaches.

One state actively supported utilization

management as an activity it hopes its contractors

do as appropriate for all services. Other officials

required that the use of utilization management for

family planning services would need to be “run by”

the state agency, indicating a process of informal

oversight of utilization control policies in this area.

Family planning-specific access requirements are

not perceived as necessary.

In keeping with

agencies’ relatively relaxed attitudes about network

composition and adequacy, officials also indicated

that they do not perceive the need for family

planning-specific access measures because they do

not perceive access to family planning services as a

problem. It is worth noting that during the period

in which these interviews were conducted, the 2019

Title X Family Planning Rule was in full effect.

Studies suggest that the rule had a notable impact

on family planning program participation.

26

To the

extent that patients and members were

experiencing access problems as capacity dropped,

this development did not appear to translate into

an area of concern for agency officials. It is

conceivable, of course, that because of the

“freedom of choice” guarantee, the need to ensure

strong provider networks is simply far less in the

view of Medicaid officials because managed care

does not act as an interrupter of care patterns of

pre-existing service accessibility. Simply put, the

“freedom of choice” guarantee acts as a braking

mechanism, alleviating the network adequacy

pressures state Medicaid programs and plans face

for other contract services that lack an out-of-

network exemption. Put another way; the out-of-

network safeguard lessens the need to “own” the

issue.

At least some agencies are focused on the rise of

religious providers that may resist family planning

as a priority activity.

Several agencies noted the

increase in religiously affiliated plans and

providers, which underscores the importance of

the “freedom of choice” guarantee. It is also an

issue that may, in some communities, complicate

comprehensive efforts to focus on elevating family

planning improvements as a managed care priority.

At least one state also noted the difficulty in

elevating these issues in legislative policy and

suggested that the most effective approach was to

incorporate family planning into larger initiatives.

Despite the absence of perceived pressing

problems, agencies recognize the importance of

family planning and express strong interest in

strategies for performance improvement.

Although

family planning emerged as an area relatively free

of pressing problems for state officials, all states

appreciated the importance of strong and effective

family planning services and appreciated the

significance and value of high-performance

systems where family planning is concerned, and

understood clearly that managed care offers a

major tool for improving family planning. Of