Northern Illinois University Northern Illinois University

Huskie Commons Huskie Commons

Faculty Books & Book Chapters Faculty Research, Artistry, & Scholarship

2024

Designing for Everyone: Accessibility, Inclusion, and Equity in Designing for Everyone: Accessibility, Inclusion, and Equity in

Online Instruction Online Instruction

Kimberly Shotick

Northern Illinois University

Follow this and additional works at: https://huskiecommons.lib.niu.edu/allfacultyother-bookschapters

Part of the Higher Education Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Online and Distance

Education Commons

Original Citation Original Citation

Shotick, K. (2024). Designing for everyone: Accessibility, inclusion, and equity in online instruction. In D.

Skaggs & R. McMullin (Eds.), Universal Design for Learning in academic libraries: Theory into practice.

Association of College and Research Libraries.

This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Research, Artistry, & Scholarship at Huskie

Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of

Huskie Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected].

CHAPTER8

Designing for

Everyone:

Accessibility, Inclusion, and

Equity in Online Instruction

Kimberly Shotick

Introduction

Online learning is increasingly an integral component of library instruction programs,

whether to reach distance learners or to supplement in-person instruction. e online

format provides unique opportunities for the design and delivery of both synchronous

and asynchronous library instruction. However, taking advantage of those opportunities

requires a disposition toward accessibility and knowledge of relevant tools and guidelines.

Increasingly, accessibility is discussed with diversity, equity, and inclusion. Inaccessible

instruction does not serve the needs of diverse learners, does not create equity in educa-

tion, and is not inclusive of all learners. However, the Universal Design for Learning

(UDL) framework that underpins much of accessibility-minded educators’ instructional

design does not go far enough to be inclusive or embrace diversity in support of all learn-

ers.

1

In fact, as of this writing, CAST, the organization responsible for the UDL framework,

is actively revising the framework to “[address] systemic barriers that result in inequitable

learning opportunities and outcomes”

2

via their initiative, UDL Rising to Equity. ese

systematic barriers manifest in the classroom, and while they need to be addressed at the

systematic level, the individual educator can make informed choices to not only foster

accessibility but equity and inclusion as well.

is chapter focuses on designing online instruction under the UDL framework in

support of accessibility, equity, and inclusion. ese are not buzzwords—they have real

Chapter8

92

implications and can be exercised through intentional instructional design. is work is

anti-racism put into practice in the (virtual) classroom. is chapter breaks down the UDL

framework into application of its parts as it relates to accessibility, equity, and inclusion.

Aer a brief overview of the ideas, each UDL guideline is dened, illustrated with exam-

ples from academic libraries, and explicitly addressed in terms of accessibility, equity, and

inclusion. Finally, I discuss assessment methods you can utilize to ensure you are meeting

instructional goals as they relate to UDL guidelines. Not only will you be able to articu-

late the impact of designing online instruction on accessibility, equity, and inclusion to

stakeholders, but you will also be able to apply the concepts to your own work in pursuit

of education for all. Aer all, as said by Andratesha Fritzgerald, educator and author of

the CAST book Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning: Building Expressways to

Success, “e work of a revolutionary antiracist—ignited by the need for change and the

body of research that points to what is possible—is burning hot with the passion to reach

all students.”

3

Recommendations on How to Read This Chapter

Shortontime?Readtheintroductionandthesummaries,thenusethestory-

boardintheassessmentsectiontodesignyourinstruction.

AlreadyfamiliarwiththeUDLFramework?Readtheintroduction,section

examples,andassessmentsection.

Newtotheseconcepts?Readtheintroductionandthesummariesrst,then

readeachsection.

Definitions

Online instruction comes in many formats and can serve very dierent purposes. Each plat-

form presents unique opportunities and challenges. For instance, Blackboard Collaborate

interfaces with other Blackboard applications and hierarchies, such as groups. However,

a university committee I serve on in support of persons with disabilities prefers Zoom’s

ability to have a sign language interpreter pinned for viewers.

Asynchronous instruction generally consists of the use of learning objects. e use of

online learning objects, such as tutorials embedded in an LMS or how-to LibGuides, has

enabled librarians to keep teaching during pandemic lockdowns and will continue to be

an important feature of library instruction beyond the pandemic era. Here, too, the tools

and their respective advantages vary. ere is no “best” tool for creating and distributing

online learning objects—the local needs and available resources will all impact t and

so there is no one-size-ts-all. What will follow is an explanation of the guidelines with

examples that use a variety of tools for both synchronous and asynchronous instruction.

In many instances, application of a guideline will be possible regardless of the tool.

DesigningforEveryone

93

Synchronous instruction in the online setting is instruction that takes place in real time.

Generally, a videoconferencing platform, such as Zoom or those built into an LMS such

as Blackboard Collaborate, is used to connect students with an educator. e delivery of

synchronous instruction varies widely, from a live reading of a PowerPoint lecture to a

ipped classroom model where students engage in group work to apply concepts—and

everything in-between.

Accessibility, in terms of online instruction, refers to the characteristics of the instruc-

tion that allow or disallow students to engage with and receive instruction. Accessibility is

a legal requirement. e Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Sections 504 and 508

of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 compel educators to make their instructional materials

accessible, including online content.

4

e standard for web accessibility is WCAG 2.0 AA,

a set of web accessibility standards created by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)

Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI).

Equity in the context of education can be summed up as giving everyone what they

need to succeed. Equity is distinct from equality, as what one person needs to succeed

may dier from another. is is especially true when considering the systematic racism

that purposefully excluded Black and Brown children from education and has incarcer-

ated them at much higher rates than white children. e cards have been stacked against

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) individuals on purpose, and as a society

we need to reckon with racial injustice, and as educators we need to understand this in

the design and delivery of our instruction. When I write in this chapter to you, I’m not

just writing to white educators but to everyone who participates in traditional systems of

education underpinned by white supremacy. However, as a white educator raised in an

era of color-blind ideology, I’m aware that my white colleagues and I are less attuned to

the systems that benet us and continue to disadvantage BIPOC individuals.

Inclusivity is a component of accessibility and equity in education because our educa-

tion is neither accessible nor equitable if we are not designing it to include all learners.

Inclusivity is tied closely to belonging. Do all your learners feel like they belong in your

classroom, online session, or whatever virtual space you have created for them?

Why focus on accessibility, equity, and inclusion?

Higher Education has increasingly focused on inclusion and equity—it is not only

a matter of doing what is right, but it is a necessary strategy for survival, as institutions

of learning become increasingly diverse. However, these institutions were built on the

backbone of white supremacy, and outcomes have reected this. e Center for Urban

Education founder argued “that it is whiteness—not the achievement gap—that produces

and sustains racial inequality in higher education.”

5

Centering education on whiteness

leads not only to racial inequities but also inequities across all kinds of dierences, from

physical ability to age, gender, immigration status, and even body size. For example, in

a case study on the group dynamics of a graduate class, the researcher observed how

whiteness operated as a dominating and othering factor in the classroom, depriving the

Asian international students of the resources of time and teacher attention while mark-

ing their perspectives as irrelevant, thus silencing them.

6

In the case study, the white

students directed most of the questioning during a lecture, which was the only option for

Chapter8

94

participating in the instruction for that class. Later, when an Asian international student

does make a motion, indicating that she has a question, it is assumed that a white student

had made the motion, further excluding the Asian international students. UDL, while not

the only solution required to address the inequities of education, provides us a tangible

opportunity to begin to recenter education and rebuild the systems that lead to (and

sustain) inequality. Aer all, “Systems are doing exactly what they were designed to do—

allow white privileged students to succeed and move ahead while others are held back.

UDL requires us to do better….”

7

White supremacy in online education has also produced inequitable outcomes for

students with diverse identities and/or characteristics. e American Library Association

(ALA) denes equity as an “assumption of dierences” and equity in action as “tak[ing]

those dierences into account.…”

8

Here, UDL and ALA have a commonality: intentional

design for those with dierences for the benet of all. While the UDL guidelines don’t

explicitly mention racism in education, they do give pathways to working against it.

9

e

guidelines can be viewed through an antiracist lens and implemented as such, especially

when combined with antiracist pedagogy, such as Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, an

educational theory that reimagines education as a site for holding up and honoring diverse

cultures.

*

is chapter does just that: oers concrete UDL practices through an antiracist

lens in support of students who have been le behind by an education system that wasn’t

built for them. While change needs to happen at systemic levels, we must acknowledge

and harness the power we do have, even if our time with students is brief.

Applying the UDL Framework

e following sections dene each of the three UDL guidelines, oer application ideas

for online instruction through an equity and inclusion lens, provide a bulleted summary,

and give a case study generously shared by an academic librarian. What you won’t nd

is a detailed description of each checkpoint nestled within the guidelines. For a fuller

explanation of the guidelines, visit CAST’s website, which goes into further detail on each

guideline: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/.

Engagement

e rst UDL principle, providing multiple means of engagement, refers to the way in

which we allow our learners to choose interactions that promote their interest, persistence,

and self-regulation. Learner motivation is varied because learners are varied. Each one of

us is unique, since not only are our brains “wired” dierently due to the DNA we inher-

ited, but we are also shaped by our experiences in life. What engages me because of my

brain chemistry and my unique cultural and personal experiences may not engage my

neighbor. My neighbor may suer, then, from a lack of interest in situations where I thrive.

When we set up learning so that there is something engaging and motivating for me and

* I rst encountered the concept of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy in the webinar “Towards a Future of Culturally

Sustaining Pedagogies” by Soa Leung and Jorge López-McKnight as a part of the University of New Mexico’s Marjorie

Whetstone Ashton Speaker Series on March 22nd, 2022.

DesigningforEveryone

95

something that is engaging and motivating for my neighbor, we both thrive, and not at

the cost of one another. Antiracist pedagogy acknowledges that the default audience in

higher education has been white, English-speaking, heteronormative, and seeks to recruit

the interest of those outside of this default. By de-centering whiteness in education, we

can shi away from a default that perpetuates inequality.

Guideline 7 of the engagement principle is about recruiting the interest of learn-

ers. is guideline asserts that accessible learning must be interesting to learners.

10

When

considering inclusivity and equity in terms of recruiting interest, we must recruit the

interest of all learners—that can mean taking a hard look at where your examples or

methods of engagement are centered. Do they center on a white, cis-gendered learner, as

academia historically has?

e three checkpoints within this guideline give us pathways to increase interest:

optimize individual choice and autonomy; optimize relevance, value, and authenticity; and

minimize threats and distractions.

11

Online learning is particularly suited to the rst two

checkpoints if the educator is mindful to take advantage of the online setting in support of

these checkpoints. For instance, learning modules may give students options for engaging

with the content. A “choose your own adventure” style module might have three options

for the same content: watch this interactive video, read this text and answer questions, or

listen to this podcast and produce a response.

e second checkpoint—optimize relevance, value, and authenticity—requires us to

design instruction that is relevant to all learners by oering instruction that is culturally

relevant and draws on the student’s own cultural wealth. Drawing on students’ cultural

wealth fosters collaboration and community and grows multiculturalism where all

students learn the cultures of one another. In an online setting, this can look like asking

students to work in a group and describe who they, in their culture and personal experi-

ences, consult as experts when trying to learn something new. In this example, students

are not only engaged by talking about their own experiences, but we can engage in critical

information literacy together in a way that honors multiple ways of being. is can be

done in an online discussion group (for asynchronous instruction) or in breakout rooms

(for synchronous instruction).

Once we’ve recruited learner interest by oering choices and honoring their expe-

riences, we must help them manage distractions. Minimizing threats and distractions

can be dicult when the threats and distractions are completely outside of our control.

However, we can oer students comfortable, safe spaces to engage in work (such as a

library—yours, or their local library, for distance learners). Assuming students have a

private, quiet space in their home to meet with you synchronously or to focus on your

asynchronous content is a privileged assumption. I’ve taught students who were homeless,

hungry, sick, grieving—we likely all have; these statuses are not uncommon. Minimizing

these types of threats and distractions primarily happens at the structural level, but you

can and should not only remind students that food, shelter, and safety are essential to

their learning but also oer them resources they can access to get those basic needs met

(whether that is through a food pantry, shelter, or a third place, such as a library, where

they can rent a room or nd a quiet corner at no cost).

Chapter8

96

Once you’ve successfully recruited their interest in ways that make the learning rele-

vant and valuable, you must sustain their interest. e three checkpoints within this guide-

line give us pathways to sustaining eort and persistence: heighten salience of goals and

objectives, vary demands and resources to optimize challenge, foster collaboration and

community, and increase mastery-oriented feedback. In any learning environment, goals

should be clearly communicated to students. I recall a time that I was teaching a nancial

literacy lesson and I had forgotten to articulate the big picture goal, yet I expected the

students to create their own individualized goals. “But why are we doing this?” a brave

student asked. I had either failed to communicate the goal in a way that was meaningful

to all my students or I had failed to communicate it at all. Either way, I was thankful for

the student’s question and quickly addressed the immediate and long-term goals. Online

learning modules should clearly state the learning goals in a way that is meaningful and

motivating to students. For example, “is module will help you better understand how to

evaluate information that you nd online so that you can choose better sources for your

paper (and get a better grade) but also so that you can make better information choices

for your personal use.”

In addition to explicitly stating goals, oering a choice of diculty based on prior

experience meets our students where they are. Designing that way lets the student try

something, like identify keywords from a research topic, and then allows the student to

adjust the level that meets this guideline. Language learning apps do this well. Popular

apps, such as Duolingo, have built-in articial intelligence that adjusts the instruction

based on performance while encouraging the learner based on what they are doing

well. Additionally, providing feedback is another dicult checkpoint to operationalize

in the online setting, especially for one-shot type instruction. However, building in

tools such as low- or no-stake quizzes that oer constructive feedback is one way to

address this need.

Providing students with a variety of tools for self-regulation is another important

aspect of the Engagement guideline. e checkpoints 9.1 (promote expectations and

beliefs that optimize motivation) and 9.2 (facilitate personal coping skills and strategies)

relate to aective tools we can provide our students to support their learning instead

of perpetuating the messages of decit thinking common in education that alienate

students. e decit thinking model characterizes students who do not perform well as

lacking instead of recognizing that it is our education system that needs xing.

12

Reme-

dial courses, for example, oer to “correct” students, many of whom were under-re-

sourced in the K-12 setting. When considering that white students have taken remedial

courses at the lowest rate of all other races, it is easy to see that not only is education

failing BIPOC students but also that the students are given the message: you do not

belong here. is type of framing and lack of addressing the real issue (the education

system) de-motives and deates students, ensuring that the prophecy of the educator

comes true. In fact, just the opposite can have incredible benets to motivation, result-

ing in higher achievement. Exercises that help learners arm their sense of self and

value have positive impacts on their learning, even without changing anything else in

the instruction.

13

e aective network, which deals with priorities, motivation, and

DesigningforEveryone

97

engagement, can clearly have a powerful impact on learners if harnessed with intention

toward inclusion.

e three checkpoints within this guideline give us pathways to promote self-reg-

ulation: promote expectations and beliefs that optimize motivation, facilitate personal

coping skills and strategies, and develop self-assessment and reection.

14

In online

learning, it isn’t always obvious to address this dimension of the aective network

because we can’t always see the motivation and coping skills in action (or lack thereof).

In a physical classroom, I can see the student who appears to be struggling with moti-

vation yawning in the corner and adjust my methods to better engage them. However,

these checkpoints are well-suited to be incorporated into information literacy programs.

e Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education describes dispositions

of “learners who are developing their information literate abilities”

15

throughout the

framework. ese dispositions are oen situated in the aective network and relate to

the idea of self-regulation. For example, in the Authority Is Constructed and Contex-

tual frame, learners “motivate themselves to nd authoritative sources” and have “a

self-awareness of their own biases and worldview.”

16

ese dispositions map perfectly

to the UDL self-regulation checkpoints of optimizing motivation and developing self-as-

sessment and reection. e Framework is full of these dispositions, so instruction that

is mapped closely to the Framework is likely to address these checkpoints in some

way. One example of how to address this guideline is to prompt students to identify

aspects of their identity that might impact their worldview. Students could engage in a

reective prompt through a discussion board or as a text entry or multimedia response

to a module prompt.

Example

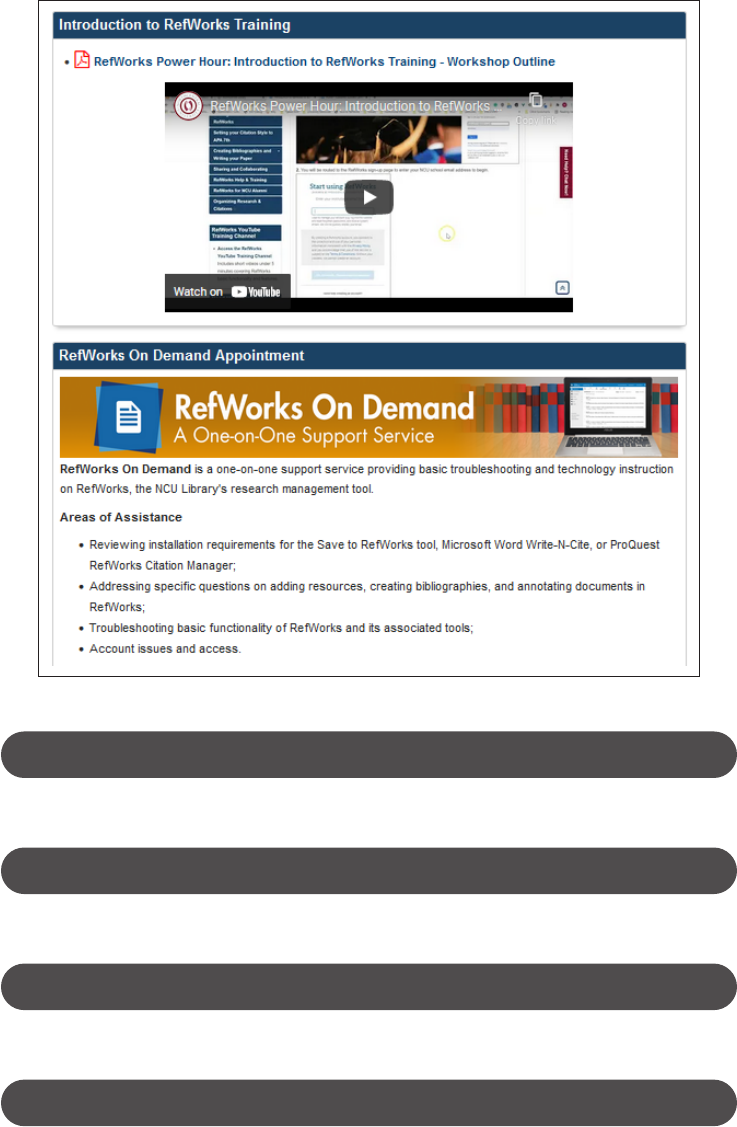

In this example, Academic Services Librarian Mercedes Rutherford-Patten and Course

Reserves & Circulation Desk Coordinator Caleb Nichols at California Polytechnic State

University, San Luis Obispo, shared their Research Ethics tutorial. e tutorial’s focus is

on ethos and types of bias in research. It is embedded within a larger Canvas LMS module

for library research that introduces students to foundational information literacy skills.

e tutorial meets several UDL guidelines, including those that come later in this

chapter. For engagement, however, the tutorial allows the user to engage in optional,

reective activities, such as taking an Implicit Association Test in a section on biases.

is example illustrates a few components of the engagement guideline. First of all,

it allows the student to engage with the content in multiple ways: via a transcript, a video,

and/or by taking a quiz. e activity is also reective and allows for personal choice.

Project Implicit oers een dierent Implicit Association Tests for the user to identify

their own biases in areas including age, disability, race, weight, and more. By oering

choice in several areas including content format, bias, and even the choice to engage in

the content at all, learner attention can be attracted and sustained across a diversity of

experiences and identities.

Chapter8

98

Figure 8.1. Screenshot from the module with the heading “Optional

Activity: Identify Your Implicit Biases,” by Mercedes Rutherford-Patten and

Caleb Nichols.

Figure 8.2. Summary of the UDL engagement dimension.

Oer accessible, varied choices that are relevant to the diverse

cultures you serve

• Drawuponthestudents’culturalwealth

• Oerresourcestominimizethreatsanddistractions

To Sustain Learner Eort & Persistence

• Explicitlystatethelearninggoalsinameaningfulway

• Allowforavarietyofdiculty

• Providefeedback

To Promote Learner Self-Regulation

• Encouragearmations

• Oercopingstrategiesrelatedtothework

• Incorporateselfreection

DesigningforEveryone

99

Representation

Student diversity is reected in many dimensions: age, background, interests, race, gender

identity, and more. However, we oen teach students how to t into a white, heteronor-

mative mold that not only doesn’t reect the whole of who we are teaching, but it also

hurts those that dier from that mold. By oering our students a multiplicity of examples

and formats, we are much more likely to meet their accessibility needs, make them feel

welcome, and arm their way of knowing and being as good.

e three guidelines in this principle relate to (1) perception, (2) language and

symbols, and (3) comprehension.

17

ese guidelines are common best practices in online

education and are well-documented in the literature. e principle recommends variation

in the way that information is presented and student choice regarding how they interact

with it. We can provide learners with multiple formats and allow for customization using

an online format. e clearest application is providing the same content in multiple ways.

In a learning module, repeating a video’s content with bullet points and graphic organizers

is more work upfront in the design phase, but pays o in learner outcomes and a reduced

need to intervene. Why wait for a student to ask for more explanation or another example,

if we are lucky enough to get such feedback? Provide the options from the start. If we can

use a tool such as YouTube or Kaltura for hosting videos, they have some built-in options

for customization. In Kaltura, for example, learners can translate captions to another

language, move the captions around, and even change their size and color. Kaltura also

has the feature of allowing users to slow down or speed up the video. W3C has a checklist

to consider when making multimedia content to make sure that your video and audio

content is accessible: https://www.w3.org/WAI/media/av/planning/#checklist.

Despite this guideline’s focus on variation, it leaves out areas where we can be inten-

tionally inclusive. Of all the guidelines, Representation has the most potential for educa-

tors to activate antiracist pedagogies, such as Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, which can

help reshape higher education as a place where all are welcomed and valued. However, as

Amanda Roth, Gayatri Singh (posthumously), and Dominique Turnbow pointed out in

their article “Equitable but Not Diverse: Universal Design for Learning Is Not Enough,”

UDL is currently missing the explicit call for intentional representation of diverse iden-

tities.

18

For that reason, I’ve added a fourth guideline to this principle: To Provide Diverse

Representation. We can provide examples and texts from a variety of cultures and iden-

tities, and our graphics should represent many ways bodies can be. Roth, Singh, and

Turnbow, for example, oered characters with racial diversity in their tutorials and found

that students not only noticed the diverse variety of characters but also overwhelmingly

preferred that diversity. e simple design choice to include characters of dierent ages,

skin tones, and body types is one way to be more inclusive.

Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy asks us to not only represent a variety of ways of being

but to also sustain them. is requires that we as educators get to know their communities

and explore the cultures and customs of the many students we serve. When the default

examples and icons are no longer rooted in whiteness, we can begin to decolonialize

education spaces and truly embrace education as a site of cultural pluralism that can enact

social transformation towards equity and inclusion.

Chapter8

100

Figure 8.3. Screenshot of two sections of the Library Guides by Marisha C. Kelly.

Figure 8.4. Summary of the UDL representation dimension.

To Provide Options for Perception

• Oermultipleformatsforthesameinformation

• Allowuserchoice/customizationwhenpossible

To Provide Options for Language and Symbols

• Varytheuseofsymbolsandlanguagetoconveyinformation

• Allowforlanguagecustomizationwhenpossible

To Provide Options for Comprehension

• Highlightmainpoints/bigideas

• Activatetheirpriorknowledgethroughexamplesrootedinavarietyofbackgrounds

Provide Diverse Representation

• Representmultipleidentitiesingraphics

• Honoridentitiesthroughexamplesrootedinavarietyofbackgrounds

DesigningforEveryone

101

Example

In this example, Marisha C. Kelly, reference and instruction librarian at Northcentral

University, provided a training program for the reference management tool RefWorks.

Prior to the creation of the training program, some asynchronous options like the RefWorks

Library Guide and general training videos from the vendor were previously available to

students; however, Kelly found that the vendor resources were not enough to support

the individualized and diverse learning needs of their users. Kelly’s program included

synchronous training options, including weekly workshops, one-on-one appointments,

live help support through phone and chat reference, and virtual study halls. In addition

to the synchronous instruction and support, asynchronous instruction included video

tutorials, library guides, and an FAQ knowledge base.

Kelly’s RefWorks instruction was diverse in that learners could choose from a wide

variety of modes of instruction (in-person workshops, online guides, or video tutorials, for

example). By oering learners a suite of tools customized for their populations, Kelly was

essentially giving the learners the whole toolbox. Creating multiple formats and modes of

instruction may seem daunting, but the time is generally concentrated upfront, and the

reward is reaching the most students and their individualized needs.

For more information about the training program, see Kelly’s poster, presented at the

Transforming Libraries to Serve Graduate Students virtual conference in March 2022:

https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/gradlibconf/2022/Posters/4/.

Action and Expression

Action and expression is the nal principle. is principle argues that learners must be able

to demonstrate their learning in meaningful ways. Within the principle are guidelines for

physical action, expression and communication, and executive functions.

Online content must rst meet accessibility requirements but must also go beyond

those requirements to be truly accessible and inclusive of all learners. Physical action in the

online setting refers to how users navigate and interact with the content online. For exam-

ple, content must be accessible to screen-reading devices, such as JAWS or NVDA, which

is a baseline accessibility requirement. Beyond that, consider how users could navigate

through content without a mouse (using keyboard shortcuts, for example) or on a variety

of devices, such as a phone. Content that is only accessible via a personal computer is not

truly accessible to everyone. In the past year, over 10 percent of Northern Illinois University

Libraries’ YouTube tutorial views came from mobile phones. YouTube uses HTML5 and

can play videos smoothly on lower bandwidths across many dierent platforms. is type

of consideration may require some technical knowledge, but it is essential to be sure that

online content works for the learner regardless of their device or internet speed.

Just as it is important for the technology to provide options to the learners to meet

their needs, we should present content options for the learner to be able to communicate

with or respond to online learning objects. For instance, if given a nal assessment aer

a series of modules, we can oer learners a choice for their response format. Online tools,

such as Voiceread, may allow the learner to choose how to respond to a question, for

example, by recording audio, typing a response, or inserting pictures. Without such a

Chapter8

102

tool, however, we can still allow for choice. For example, if working synchronously with

students, we could ask students to respond to an “exit ticket” that is either a three-sentence

summary about the research process, a meme that represents the research process, or a

link to a video or song about the research process. We could post them on a shared space,

such as a Jamboard or Padlet, or simply emailed or messaged to us. When this type of

hands-on assessment is too dicult to scale to large classes or courses with many sections,

we can work with the course’s instructor in designing a exible assessment that the instruc-

tor grades. ere are many opportunities to oer choice, and doing so not only leads to

more inclusive teaching but also to more interesting and creative work from learners.

19

Finally, providing options for executive functions gives learners the tools they need to

comprehend the material by dealing with our executive functions appropriately. Execu-

tive functions allow us to control the short-term impulses that come up and focus on the

task at hand.

20

If we think of the brain like a car driving through a busy city street, we can

imagine the many obstacles: pedestrians, other cars, cyclists, stop signs and stop lights.

Perhaps this is a street that we grew up traveling and we get all the green lights. Not so

hard. Imagine, though, we’re driving in a dierent country and don’t know what the signs

mean, and pedestrians jump out randomly. Scenario one is easy, but the second? Nearly

impossible. Learners may or may not be familiar with the material, mode of instruction,

unspoken expectations of the classroom, and technologies used. Learners may have been

given advantages, as in the rst scenario, or may be disadvantaged by the scenario placed in

front of them. To equalize the playing eld, we must consider equitability—and that means

focusing on the learners for whom the “traditional” route doesn’t work and building tools

to help the learner reach their goal. inking about executive function, distractions come

in many packages. Giving learners tools so that they can scaold the instruction is one tool

that we can utilize to keep all learners on track. For example, checklists before and/or aer

the content can help remind the learner of the goal (think: signs saying, “this way!”) as well

as make sure that they are ready to move on. Creating these little stops on their journey

can not only build condence but it can also allow learners to regulate their own learning.

Also, adding progress cues, such as numbering modules and/or providing a progress bar,

allows learners to monitor their own learning. is can be extremely important for learn-

ers who have time constraints, such as families and jobs that require their time. Fitting in

2/10 sections of a learning module between obligations seems much more possible than

engaging in content of unknown size. For this reason, the modules that students of English

composition take at Northern Illinois University are chunked up into several units that

always begin with instructions on how to complete the module and an outline of content.

Example

In this example, Kelly Blanchat, undergraduate teaching and outreach librarian at Yale

University Library, created an online worksheet that guides students through various

library research processes and facilitates analysis of research concepts. e form includes

logic that branches o students who are having trouble into pages with support, such as

a video tutorial reinforcing the concepts or processes needed to continue. e worksheet

then guides the students through the process of draing a research question, generating

keywords, and conducting an advanced search for articles.

DesigningforEveryone

103

Blanchat uses the worksheet prior to both in-person and synchronous instruction

in a ipped classroom model. For the “live” instructional portion, Blanchat guides the

students through another worksheet with their article citations from the rst worksheet

they completed prior to class and facilitates their deeper thinking about information

literacy concepts which they discuss as a group.

roughout her interactive worksheet (built using a Google Form) Blanchat oers

options for navigating the content (such as giving a direct link for a YouTube video in

case the embedded video is too small on their device) and provides options for scaold-

ing using form logic to supplement the instructional content when it is needed. Also, the

worksheet supports eective executive functioning by allowing the user to process one

piece of information at a time and use the back button to reference previous material. e

student’s responses are sent to them at the end of the session.

To see Blanchat’s full worksheets and instructional material, visit: https://drive.google.

com/drive/folders/1LOCNa2KY5WhcGjLPFG2kq2Q4HSs0-Svv.

Figure 8.5. Screenshot of two sections from the interactive worksheet by

Kelly Marie Blanchat, undergraduate teaching and outreach librarian at

Yale University Library.

Chapter8

104

Figure 8.6. Summary of the UDL action and expression dimension.

Assessing Your Accessibility Eorts

It can be overwhelming to try and implement new guidelines across your instructional

design, especially if you have been teaching one way for a while. You can begin with small

changes within your existing plans, however. Begin by assessing how accessible, equitable,

and inclusive your teaching is, and either (1) nd the place that needs the most attention

or (2) nd a solution that is the easiest to implement to get you started. You may learn

that some of the smallest changes make the biggest impacts.

ere are a variety of tools available to help you design accessible and inclusive learn-

ing. ese tools are either freely available or are available via an LMS, natively or as

add-ins. While not exhaustive, some of the major tools used in education are described

below.

Blackboard Ally. Blackboard Ally is a paid tool that can be used as a standalone

tool for websites or embedded in any LMS, not just Blackboard. It not only identies

accessibility issues, it also translates les into a variety of accessible formats and provides

institutional reporting on accessibility. For more information on using Blackboard for

LMS, visit https://www.blackboard.com/teaching-learning/accessibility-universal-design/

blackboard-ally-lms.

NVDA. NVDA is free, open-source screen-reading soware. If you are sighted, you

may want to download the soware to test navigation of your online content via a screen

reader. However, be mindful that a sighted person’s experience with screen readers will be

dierent from that of regular users who may be savvy at navigating websites with the so-

ware. e soware may be downloaded for free at: https://www.nvaccess.org/download/.

UDOIT for Canvas. Universal Design Online Content Inspection Tool (UDOIT)

was created by the Center for Distributed Learning (CDL) at the University of Central

To Provide Options for Physical Action

• Provideavarietyofwaysstudentscannavigateandinteractwiththecontent

• Optimizeyourmaterialsforassistivetechnology

To Provide Options for Expression and Communication

• Givestudentsculturallyrelevantoptions

• Givestudentsformatoptionsfortheirresponse

To Provide Options for Executive Functions

• Provideoptionsforscaolding

• Usegraphicorganizers,check-lists,andguides

DesigningforEveryone

105

Florida (UCF). UDOIT is a tool that checks Canvas courses for accessibility. Although it

was created for faculty at UCF, the program is open source, and the code can be down-

loaded from their GitHub page. For more information, visit https://cdl.ucf.edu/teach/

accessibility/udoit/.

WAVE tool. e Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool (WAVE) does just that: evaluates

the accessibility of websites. is free tool looks for WCAG errors and facilitates human

evaluation of the issues, along with information to further educate the evaluator. For more

information and to use this free tool, visit https://wave.webaim.org/.

e following worksheet

*

can help you plan a lesson or module using UDL strategies.

Lesson or

Module Name/

Number:

Description/

Information

Additional

format

UDL Strategy Accessibility

and Equity

Consideration

Objectives

Readings Engagement:

Diverse

Representation:

Lecture

Presentation and/

or Instructional

Video

Engagement:

Diverse

Representation:

Discussion

Questions

Engagement:

Diverse

Representation:

Activity Engagement:

Diverse

Representation:

Additional

Resources/

Supporting

Materials

Engagement:

Diverse

Representation:

e following chart is a summary of some of the implementation ideas mentioned in

this chapter. is is merely a sampling of ideas to hopefully spark ideas for how you can

apply UDL concepts (with a Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies twist) in your own teaching.

* is worksheet is a modied version of a worksheet created by Stephanie DeSpain, assistant professor in early child-

hood education at Northern Illinois University, which she generously shared with me and gave me permission to edit

and reproduce it here.

Chapter8

106

Method Engagement Representation Action and

Expression

Asynchronous Synchronous

Explicitly state

module objectives.

X X X

Use discussion

boards and have

peers respond to one

another.

X X X

Oer students a

choice of activities or

modules that have

the same learning

outcomes.

X X X X

Have students write

about their prior

knowledge.

X X X X

Ask for (and use)

students’ names,

pronunciations, and

pronouns.

X X X

Provide resources

for students with

a variety of needs

(where to check out

a laptop, how to

access WiFi, quiet or

collaborative places

to study).

X X X

Oer the same

content in multiple

formats (html text,

image with alt text,

captioned video).

X X X

Provide a glossary

dening terms such

as “database” and

“keyword”.

X X X

Provide graphics

that represent a

variety of identities

(and describe them

accordingly using alt

text).

X X X

Include critical

information literacy

framing and

allow for student

reection—for

example, asking them

to explore their own

information privilege

before introducing

databases.

X X X

DesigningforEveryone

107

Method Engagement Representation Action and

Expression

Asynchronous Synchronous

Use low- or no-

stake quizzes with

immediate feedback

to let students check

their understanding.

X X

Use symbols, bullet

points, and other

cues to highlight

important points.

X X X

Allow student

choice in assessment

activities—for

example, they can

write a short response

or take a short quiz.

X X X X

Provide armations

to sustain student

motivation.

X X X X

Conclusion

Integrating the UDL principles into online instruction is not just about making learning

more accessible to individuals with disabilities, it encourages inclusion of all learners and

allows education to be more equitable. Combining UDL principles within a framework

of antiracist pedagogy, such as Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy, instructional design can

break from the excluding practices that are baked into systems of education and truly be

inclusive of all learners.

Notes

1. Amanda Roth, Gayatri Singh, and Dominique Turnbow, “Equitable but Not Diverse: Universal Design for Learn-

ing is Not Enough,” In the Library with the Lead Pipe (May 26, 2021): https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.

org/2021/equitable-but-not-diverse/.

2. “Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2,” CAST, last modied 2018, https://udlguidelines.cast.org.

3. Andratesha Fritzgerald, Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning: Building Expressways to Success (CAST, Inc.,

2020).

4. Brady Lund, Creating Accessible Online Instruction Using Universal Design Principles (Washington, DC: Roman &

Littleeld, 2020).

5. Estela Mara Bensimon, “Reclaiming Racial Justice in Equity,” Change 50, no. 3/4 (May 2018): 95–98, https://doi.org/

10.1080/00091383.2018.1509623.

6. Robin J. Diangelo, “e Production of Whiteness in Education: Asian International Students in a

College Classroom,” Teachers College Record 108, no. 10 (October 2006): 1983–2000, https://doi.

org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00771.x.

7. Fritzgerald, Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning, 49.

8. “ODLOS Glossary of Terms. About ALA,” American Library Association, September 7, 2017, http://www.ala.org/

aboutala/odlos-glossary-terms.

9. Fritzgerald, Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning.

10. Anne Meyer, David H. Rose, and David Gordon, Universal Design for Learning: eory and Practice (CAST, Inc.,

2014).

11. Meyer, Rose, and Gordon, Universal Design for Learning.

12. Eamon Tewell, “e Problem with Grit: Dismantling Decit inking in Library Instruction,” portal: Libraries and

the Academy 20, no. 1 (2020): 137–59, https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2020.0007.

Chapter8

108

13. Meyer, Rose, and Gordon, Universal Design for Learning.

14. Ibid.

15. Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, American Library Association, Text, Association of

College & Research Libraries (ACRL), February 9, 2015, https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework.

16. Framework, American Library Association.

17. Ibid.

18. Roth, Singh, and Turnbow, “Equitable but Not Diverse.”

19. Carli Spina, Creating Inclusive Libraries by Applying Universal Design: A Guide (Washington, DC: Rowman & Little-

eld, 2021).

20. Meyer, Rose, and Gordon, Universal Design for Learning.

Bibliography

American Library Association. Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Association of College &

Research Libraries (ACRL). February 9, 2015. https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework.

———. “ODLOS Glossary of Terms.” About ALA. September 7, 2017. https://www.ala.org/aboutala/

odlos-glossary-terms.

Bensimon, Estela Mara. “Reclaiming Racial Justice in Equity.” Change: e Magazine of Higher Learning 50, no. 3/4 (May

2018): 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2018.1509623.

CAST. “Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2,” Last modied 2018. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/.

Diangelo, Robin J. “e Production of Whiteness in Education: Asian International Students in a

College Classroom.”Teachers College Record108, no. 10 (October 2006): 1983–2000.https://doi.

org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00771.x.

Fritzgerald, Andratesha. Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning: Building Expressways to Success. CAST, Inc., 2020.

Lund, Brady. Creating Accessible Online Instruction Using Universal Design Principles. Washington, DC: Roman & Little-

eld, 2020.

Meyer, Anne, David H. Rose, and David Gordon. Universal Design for Learning: eory and Practice. CAST, Inc., 2014.

Roth, Amanda, Gayatri Singh, and Dominique Turnbow. “Equitable but Not Diverse: Universal Design for Learning Is

Not Enough.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe (May 26, 2021). https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2021/

equitable-but-not-diverse/.

Spina, Carli. Creating Inclusive Libraries by Applying Universal Design: A Guide. Washington, DC: Rowman & Littleeld,

2021.

Tewell, Eamon. “e Problem with Grit: Dismantling Decit inking in Library Instruction.” portal: Libraries and the

Academy 20, no. 1 (2020): 137–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2020.0007.