Arcadia University Arcadia University

ScholarWorks@Arcadia ScholarWorks@Arcadia

Faculty Curated Undergraduate Works Undergraduate Research

2021

Justifying Force: Police Procedurals and the Normalization of Justifying Force: Police Procedurals and the Normalization of

Violence Violence

Emily Brenner

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/undergrad_works

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Brenner, Emily, "Justifying Force: Police Procedurals and the Normalization of Violence" (2021).

Faculty

Curated Undergraduate Works

. 79.

https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/undergrad_works/79

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at ScholarWorks@Arcadia.

It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Curated Undergraduate Works by an authorized administrator of

ScholarWorks@Arcadia. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected].

1

Justifying Force: Police Procedurals and the Normalization of Violence

Abstract

Much like the CSI effect in forensic crime dramas, portrayals of law enforcement

in crime media can potentially skew a viewer’s perception of what the profession actually

entails. Many studies address the depiction of law enforcement in the media, but few

solely examine the use of force by television police officers, and the impact this may

have on frequent viewers. In an era of calls for accountability over growing attention

towards police brutality and misconduct, the media as an influencer has the potential to

play a role in how real-world instances of brutality are perceived, and more importantly,

how it is justified. This paper serves to analyze the portrayal of use of force and

normalization of violence in popular police procedurals and how characters within the

context justify their use of force. Using a content analysis, a full season of the shows

Chicago PD, Law and Order: Special Victims Unit, and Blue Bloods were analyzed for

the use of force by law enforcement against persons of interest. The portrayal of force

was found to be, in a majority of cases, justified or considered necessary. Consequences

for actions were few and far between, rarely lasting beyond the scene. As crime drama

viewers were not surveyed as part of this study, the impact of a positive, justified

portrayal of the use of force and excessive force can only be speculated. However,

accompanying literature demonstrates the portrayal of excessive force as a necessity

plays a role in viewers justifying real-world instances of police use of force.

2

Introduction

Nielsen ratings have consistently ranked crime dramas in the top 20 most popular

television dramas, proving to be a major source of entertainment for cable viewers since

the 1960’s hit Dragnet (Donovan and Klahm 2015; Kappelere and Potter 2018). Crime

dramas are recognized as fictionalized media which depict some form of the criminal

justice system, oftentimes dramatized or over-exaggerated. The subgenre of police

procedurals has risen in popularity, in which the daily work and lives of precinct officers

is depicted. These shows portray officers who are presented with a case each episode they

work to solve, involving interrogations, arrests, convictions, and the occasional use of

force or excessive force throughout. Officers in these shows may use force when dealing

with suspects for a multitude of reasons: they instinctively believe the suspect is the

perpetrator, the suspect is noncompliant, or to add overall themes of drama, action, and

intensity to the show.

Excessive force, while controversial when utilized by real-world law

enforcement, is an added element of action to crime dramas and reality-based crime

shows. Due to the presence of force throughout a majority of popular crime dramas, it is

worthwhile to examine what these portrayals entail: how they are framed within an

episode, and ultimately how they are perceived by viewers. In addition to this, the cues

that establish if the use of force to the degree it is shown is acceptable and justified, or

considered an abuse of power helps to distinguish the role force plays overall. This study

seeks to analyze how the force is portrayed in police procedurals. As a result, this

literature may aid in better understanding the role police procedurals play in the depiction

of the use of force, and ultimately how this may impact viewers.

3

Literature Analysis

Police Portrayals in Crime Dramas

Crime dramas are arguably one of the most watched genres in terms of cable

television, with an overwhelming number of viewers unfluctuating throughout the past

several decades (Briggs, Rader, and Rhineberger-Dunn 2017; Arntfield 2011; Donovan

and Klahm, 2015). Throughout its evolution, crime dramas and police procedurals have

consistently depicted officers as heroes of their community who solve new crimes with

each episode. Television officers and detectives, however, have not always been noble:

Andy Sipowicz of NYPD Blue and the various officers of The Wire saw the ushering in of

the bad cop subgenre of police procedurals (Sargent 2012). Officers such as Sipowicz

used excessive force frequently as a tool in their investigations, an added component to

be used as entertainment in their respective shows.

The use of force becomes an anticipated facet of these shows. In The Wire,

violence and excessive force are recurring themes which play a significant role in the

morality of characters. Force is predominantly used against victims deemed deserving of

it, framing violent acts as justifiable (Masur and McAdams 2019). This is common in

most portrayals of force in crime dramas, whether they be fictionalized or reality-based

(Color of Change and The USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center 2020; Masur and

McAdams 2019; Callanan and Rosenberger 2011; Donovan and Klahm 2015; Sargent

2012). Despite frequent portrayals of violence and brutality, the audience is given a

variety of reasons for the justification of force, such as a noncompliant or hostile suspect,

or the frustrations of a detective trying to keep their city safe.

4

When observing a character using force objectively, it may be difficult to justify

their actions against the suspect or person of interest. In order to combat this, shows

provide viewers with background knowledge beyond justification for the immediate

action. Initially by establishing a character as a protagonist, the character is framed as

having their actions justified as the viewer is watching through their lens, and thus better

understanding their motives (Schubert 2017). Backstories meant to establish empathy

enable viewers to pardon their actions as a result, as well as to establish familiarity with a

character. In some cases, an offending officer who receives the support of the audience

may be regarded as an anti-hero. Defined as a “morally flawed character”, the character is

framed to be justified in their actions, with the show allowing the viewer to connect with

them despite their flaws through their background story, narration, or overall role they

play (Schubert 2017:25). The viewer finds themself rooting for a character they have

attached themself to, despite the excessive force they may use or violence they create.

Myths and Realities

While crime dramas depict a lifestyle characterized by excitement and constant

action, most notably through documentary-style filming of COPS and Live PD, this is not

the case for the character’s real-life counterparts. However, if television executives chose

to run a show that realistically portrayed police officers, “it would go off the air due to

poor ratings” (Kappeler and Potter 2018:273). On average, an officer on television—be it

in documentary format or fictional crime drama—experiences more time involved in

crime-fighting throughout the course of one episode than an actual officer may

experience their entire time working in their precinct. According to the Federal Bureau of

Investigations Universal Crime Report (2016), in 2015, 505,681 violent crimes had been

5

reported, and over 628,000 people were working that year as police officers. What this

shows is less than one violent crime per police officer had been reported that year

(Kappeler and Potter 2018). Despite frequent portrayal, the use of force is not employed

by officers nearly as often as suggested in crime dramas (Boivin, Gendron, Faubert, and

Poulin 2017). This further shows how little “action” police officers, on average, see while

on the job.

A popular claim used to defend an officer’s use of force is that the profession is

incredibly dangerous, as police can be involved with violent offenders. Said claim is

usually made after there is a reported incident of an officer using excessive force on a

suspect (Gallagher 2018). The reality, however, is officers are much less likely to be put

in extreme danger or killed on the job than crime dramas would suggest. Kappeler and

Potter (2018) state: “[police officers are] many times more likely to commit suicide than

to be killed by a criminal” (Fleetwood 2015; 2018:279). This is because, on average,

police officers do not see as much action as media depictions of the job would lead

people to believe. While the job itself is not free of any kind of danger, on average, police

officers are not at the risk many have come to believe as a result of frequent viewing of

crime dramas and crime-related media centered on law enforcement (Kappeler and Potter

2018).

Media Impact on Viewers

In the realm of crime-related media, fictionalized television shows have shown to

not have as great of an impact on viewers as news media and reality-based crime dramas,

with experiences with law enforcement proving to be more influential when determining

one’s attitude towards law enforcement (Callanan and Rosenberger 2011; Dowler and

6

Zawilski 2007, Van den Bulck, Dirikx, and Gelders 2013). Researchers have instead

noticed that while fictional portrayals do not affect overall attitude, they do play a part in

how viewers interpret the use of force and misconduct. In a study to determine viewer

perceptions of misconduct in crime media, Dowler and Zawilski (2007:194), found

frequent crime media consumers who were consistently exposed to excessive force had

an “increased belief in the frequency of police misconduct”.

This was consistent with a study done by Boivin et al. (2017) in which

participants were exposed to fictionalized videos of police brutality. The videos did not

change participant’s attitudes towards police, but exposed participants were more likely

to believe officers engaged in higher rates of the use of force compared to participants

who were not shown the video. In addition to this, both the experimental group and the

control group did not condemn the officers involved and found justification for their

actions. Boivin et al. (2017) note this may be a result of participants believing the use of

force is a necessary tool when apprehending suspects.

To analyze how the portrayal of the use of force impacted frequent crime drama

viewers, Donovan and Klahm (2015) conducted a content analysis on three separate

crime dramas: The Mentalist, Criminal Minds and NCIS. From watching one season (23-

25 episodes) of each show, officers were portrayed “frequently [engaging] in force”

(2015:1275). Force was portrayed as necessary, as the perpetrators often were hostile,

resistant, or posed a danger to the life of the officer. Donovan and Klahm (2015) suggest

this exposure to the use of force by television officers may make viewers more likely to

believe the use of force is justified. They explain: “The casual use of civil rights

7

violations with no repercussions may prime the viewers to believe that this is how

policing is and ‘should’ be done” (Donovan and Klahm 2015:1264).

In most instances of excessive force being used, the action is framed to support

the officer using force against the suspect, justifying the action by depicting the suspect

as a threat to the officer’s life and leaving them with no choice but to use force. The

conclusion viewers reach is despite these violations being made, the end justifies the

means, making the use of force warranted. Donovan and Klahm (2015:1271) found while

watching crime dramas had “no effect on perceptions regarding the degree to which the

police actually use force”, nearly 79% of viewers perceived use of force as justified while

making arrests. These results are consistent with Boivin et. al (2017) and Dowler and

Zawilski (2007), as participants in each study believed force was more frequently used by

officers, and in most cases, justified.

The justification of the use of force in crime dramas is just as prevalent as the use

of force itself. Multiple studies and content analyses note the use of force as being framed

as a necessity in dealing with offenders, who are often portrayed as hostile (Color of

Change et al. 2020; Van den Bulck, Dirikx, and Gelders 2013; Callanan and Rosenberger

2011; Boivin et al. 2017; Color of Change et al. 2020). Officers in crime dramas are also

shown to be successful in solving cases. This depiction often suggests an officer’s use of

force aided in the solving of a case. Despite the excessive use of force, officers are rarely

shown in a negative light; their desire to make the community they serve safer outweighs

any violence they may have caused. This ultimately solidifies the narrative that the ends

justify the means in crime dramas, further justifying the use of force.

8

Race is a significant factor in how a viewer can be impacted by entertainment

media consumption. Several studies have found people of color, especially Black people,

are less likely to have their attitudes on law enforcement impacted from viewing crime

dramas (Donovan and Klahm 2015; Callanan and Rosenberger 2011; Dowler and

Zawilski 2007). White civilians and nonwhite civilians have significantly different views,

attitudes and encounters with law enforcement as a result of how law enforcement has

historically treated people of color (Alexander, 2010). In a study conducted on the

influence of crime-related media and viewers attitudes towards law enforcement, authors

Callanan and Rosenberger (2011) found that race was a significant factor in determining

how a viewer would be impacted by frequent crime media consumption. Black

participants were found to have a lower opinion of law enforcement compared to white

participants, and white participants demonstrated having a greater impact on attitudes

towards police after frequent viewing of crime-related media. This is consistent with the

findings of Dowler and Zawilski (2007) and Donovan and Klahm (2015).

This is most likely due to a combination of factors. Police portrayals in crime-

related media, more so reality-based crime dramas and fictional crime dramas, are almost

always positive. Law enforcement benefits from positive portrayal as it is believed to

raise public trust, as well as aid in solving cases by communicating details to the public

(Van den Bulck, Dirikx, and Gelders 2013; Rantatalo 2016; Cooke and Sturges 2009;

Boivin et al. 2017). Although fictionalized crime dramas have shown to have little effect

in changing attitudes towards law enforcement, their persistence in portraying officers as

everyday heroes continues to contribute to a positive portrayal.

9

Callanan and Rosenberger (2011) state that, despite positive portrayals,

communities and people of color have historically had negative interactions with officers.

They note officers regularly employed “aggressive tactics and violations of civil rights”

against communities of color under the guise of fighting the War on Drugs in the 1990’s.

Racial profiling and targeted practices and sweeps against these communities further

worked to establish a “history of suspicion and mistrust” against law enforcement

(Callanan and Rosenberger 2011:183). Beyond the War on Drugs, historical accounts of

the Civil Rights Movement and the Jim Crow era have noted the systemic racism which

permeates the U.S. criminal justice system and ultimately has created an entirely different

experience for people of color, especially Black people (Alexander 2010). As a result,

this history has a greater impact on people of color than portrayals in various media on

overall attitudes. White people, who did not experience this treatment or did not to the

same degree as people of color, do not have this history acting as a buffer. The likelihood

that their attitudes towards law enforcement will be more positive as a result of

consuming a form of crime-based media is therefore higher than people of color.

Ultimately, these studies demonstrate that crime-related media, specifically crime

dramas, can play a role in a viewer’s relationship with real-world counterparts of what

they observe on television. Unlike cultivation theory, which suggests viewers who

consistently watch crime dramas will be impacted by them in some fashion, viewers may

use the media they consume to justify previously held opinions or attitudes (Coenen and

Van den Bulck 2016; Brown, Lauricella, Douai, and Zaidi 2012). When consistently

consuming crime dramas, in which the use of force is depicted and justified in near equal

10

amounts, the viewer may use this media to further validate their beliefs and reinforce the

idea that all force is justified when utilized by law enforcement.

Public Sphere Theory

After analyzing the data presented and recognizing how sensationalized law

enforcement is in crime drama and its impact on viewers, Habermas’s (1989) theory of

the public sphere can be applied to assess how public opinion is formed. The public

sphere itself is a “realm accessible to all citizens in which ‘the activities of the state could

be confronted and subjected to criticism,’” this ideally would allow the public then to

examine, criticize, and understand better the state or interest groups at hand— in this

case, police officers and the criminal justice system (Mawby 2010). Habermas

(1989:175) argues a transformation of the public sphere has taken place, in which private

organizations disguised as representatives for the public invade the sphere. This creates

tension amongst the public and in result hinders any critical debate from taking place, yet

still maintaining the facade of a space only populated by the public.

It can be argued that the media, whether news or entertainment, has done this

successfully through opinion management. “Sectional interests” refers to interests of the

state or media; this serves as the basis of shaping public opinion within this sphere to

“motivate conformity”. In this context, conformity means to comply with the general

attitudes and beliefs held within the public sphere to form public opinion. Habermas

(1989:241) defines “public opinion” as “people’s attitudes on an issue when they are

members of the same social group”. Law enforcement and media outlets have long held a

symbiotic relationship, used in part for the benefit of both parties (Coenen and Van den

Bulck 2016; Van den Bulck, Dirikx, and Gelders 2013; Rantatalo 2016; Cooke and

11

Sturges 2009). It is possible that the media acts as a motivator of conformity by

introducing positive portrayals of law enforcement, despite displays of excessive force of

violence, to the public sphere. This hinders critical debate as a private institution is

considered to be more powerful than the individual, and their sectional interests may be

projected onto the public for the purpose of conformity. This would prove to be

beneficial to law enforcement as an individual body as it works to boost public morale

and trust, even in the case of officers being portrayed in an objectively negative light.

This conformity can be seen when viewers of crime dramas make claims such as

“being a police officer puts one at risk of immediate danger” or when viewers draw their

overall knowledge of and opinions about the criminal justice system from crime-related

media. By using various forms of media, the society within the public sphere can be

manipulated or swayed to believe what the “interest group” prefers, with conformity

being the preferred opinion. “Interest group” in this context is the general authority or

more specifically law enforcement, and to whom Habermas (1989) refers to as the

bourgeois class. The preferred opinion of law enforcement then, in this case, would be

that police officers can do no wrong even when using excessive force— as many assume

they are justified, resulting from their character counterparts on television being justified

when using force and often exempt from repercussions.

Methods

Sampling

Using a purposive sampling method, the sample consisted of one season from

three police procedural shows, approximately 22-23 episodes each. Chicago PD, Law

and Order: Special Victims Unit, and Blue Bloods were selected based on popularity

12

amongst currently airing crime dramas (TV Series Finale 2020a; TV Series Finale 2020b;

TV Series Finale 2020c). Crime dramas which did not follow the everyday experience

and cases of law enforcement were excluded from selection, as were any reality-based

crime dramas. Individual seasons of selected shows were determined after pilot testing

the first 14 episodes from seasons in order to find seasons with the most data available to

be coded. Purposive sampling was necessary for this study as consistent results were

achieved through the analysis of significant amounts of data. Season 3 of Chicago PD, 10

of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit (SVU), and 1 of Blue Bloods were then selected

(TV Guide 2020a; TV Guide 2020b; TV Guide 2020c). Episodes were accessed through

the streaming services Prime Video and Hulu. Only episodes within the chosen season

were analyzed. Each episode was viewed in complete at least once, with many episodes

re-watched for accuracy in coding.

Coding

In order to analyze the use of force and the role it plays in police procedurals,

every individual instance of force and excessive force were recorded. This could mean an

entire scene in which an officer uses force against a Person of Interest (POI) is regarded

in multiple sections. Instances of physical or verbal force were at times separated by

dialogue between characters or other non-force related actions. Coding these instances as

individual rather than collective allowed for a more accurate dataset. Individual scenes

were analyzed and coded accordingly to the actions taken by both the officer and POI.

The following themes were identified: the force that took place, the justification

of the act, the presence of any consequence and its impact, the guilt or innocence of the

POI, and the success of the episode investigation. Within each theme, there were several

13

sub-categories. For force, the level of severity was coded as excessive or non-excessive;

how these two categories differentiate are discussed below. It was then noted if the action

was physical force, verbal force, a nonverbal threat, or a combination of these codes.

Further codes were used to narrow down the act, by noting if a tool or weapon was used,

such as a rifle, taser, car, or other foreign object. Abusive language and threats were

recorded alongside general verbal force, as well as codes for hitting, kicking, rough

handling, joint manipulation, and the rough application of handcuffs. If the POI was

fatally wounded, the death was coded.

The justification of each instance was then coded. Justifications were separated by

how the justification was framed for the viewer: acknowledged, implied, or no

justification present. Reasons for justification included the implied guilt of the POI,

seeking information or interrogating, in defense of a perceived threat, evading officers,

and whether the POI was armed. The demeanor of the POI, if relevant, was included as

well; hostile, non compliant, non civil, or undercover POIs were coded. Furthermore, if

the instance of force or violence was framed as necessary to the audience, it was coded as

such.

Should a consequence be administered in response to an officer’s use of force, the

consequence was analyzed and coded. The rank or role of the person administering the

consequence was recorded, including a code for a public response—in all three shows,

the role of the general public was considered an influential body that could impact how

the officer’s use of force is perceived. The purpose of coding the rank of the person

administering the consequence was to demonstrate severity: in cases in which an above-

ranking officer administered a consequence, it was considered more significant and

14

severe than one delivered by someone of a lower rank. The meaningfulness of the

consequence was coded as a verbal reprimand, physically removing the officer from the

scene, if their job was impacted, and how if it was. A code for unknown consequence was

included if the implication of a consequence was vague or continued past the end of the

coded season.

Following these three themes, each episode was recorded for their clearance rate.

If the episode ended with the perpetrator caught and convicted, the case was considered

successful. If the perpetrator was identified to viewers but no formal justice was brought,

this was recorded as well. The purpose of this code is to be used to understand how the

use of force can potentially play into how a case is solved. Lastly, the scene was coded to

determine if the POI receiving force was proven to be guilty, innocent, undercover, or

was not guilty but associated with the guilty party. This was done to determine the

validity of the officer’s actions, and examine the difference between an officer using

force against both innocent and guilty parties.

15

Data Analysis & Discussion

Results

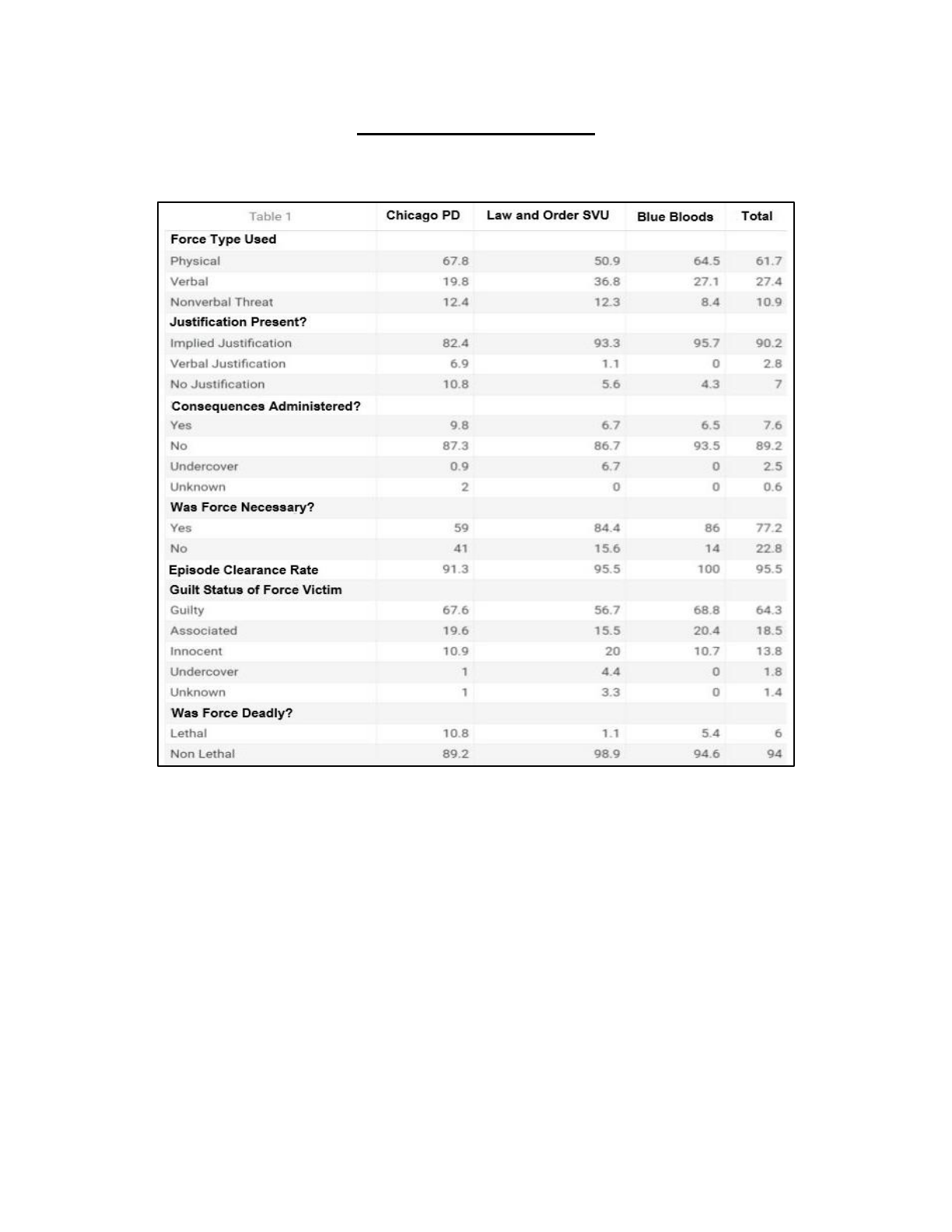

Table 1 displays percentages of main themes broken down per show and overall percentage

Criminal justice scholars have debated how to properly define “force” and

understand what exactly constitutes it, resulting in a variety of definitions (Donovan and

Klahm 2015). In this study, “use of force” will be defined as when the actions of an

officer causes physical or emotional harm in the process of identifying, apprehending,

questioning or any other interaction with a suspect or perpetrator. Table 1 exhibits the

data collected from the content analysis, displaying each major category analyzed: Force,

Justification, Consequences, Guilt Status, and Clearance Rate.

16

Force

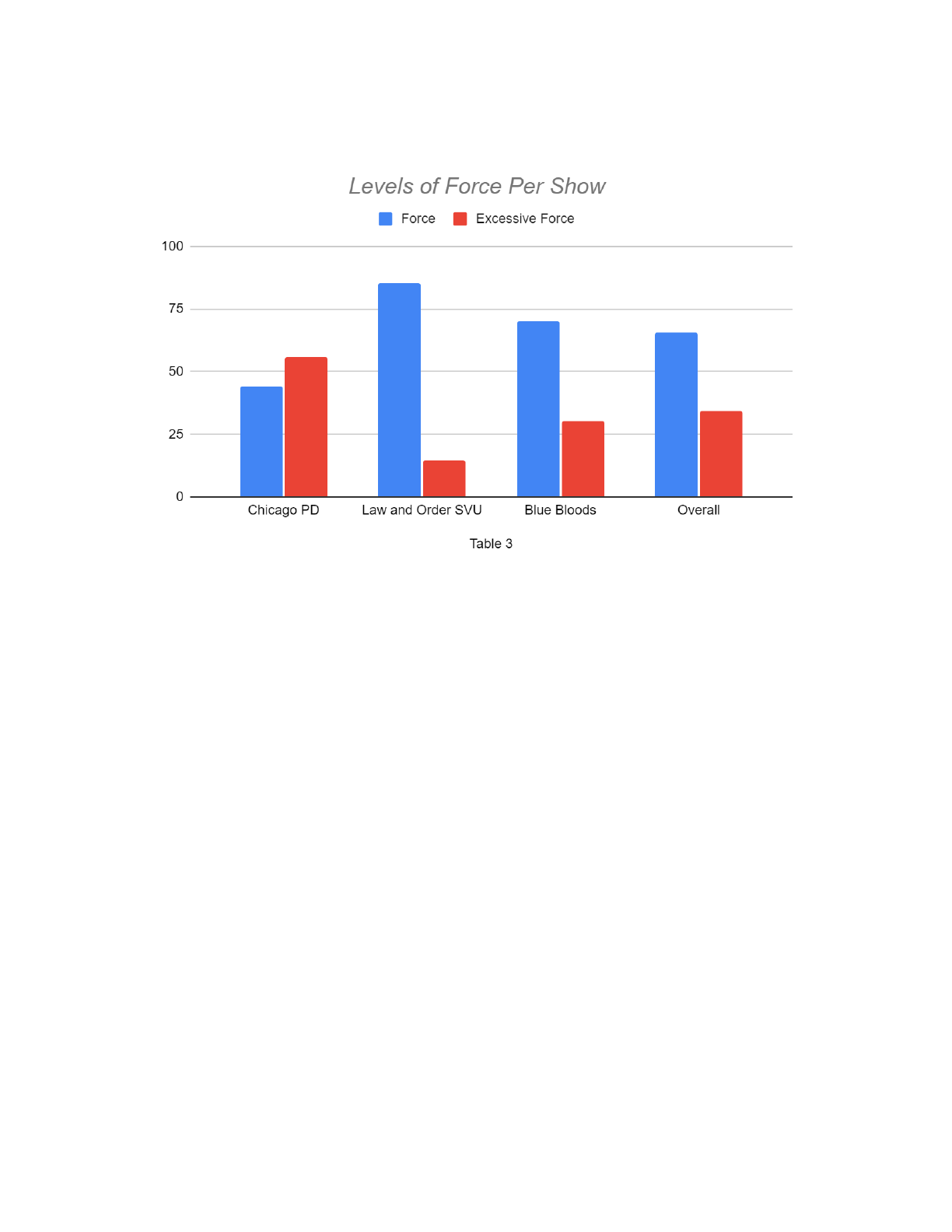

Table 2 displays the levels of force per show in percentages

A total of 285 instances of force or excessive force were recorded from the

sample (n=67), with only one episode not containing any force. Chicago PD contained

102 instances, Law and Order: SVU contained 90 instances, and Blue Bloods contained

93 instances. Four of the 285 counts were implied instances which happened off screen,

and 17 of the 285 instances were lethal. Persons of Interest were predominantly white

(74.3%) men (92.2%), and officers involved were predominantly white (84.6%) men

(85.3%) as well. All shows were more likely to portray the use of force over excessive

force (34.4%), with an overall 65.6% of the use of force portrayed. Chicago PD had the

highest rate of excessive force used (55.9%), making it the only show coded with a

higher rate of excessive force than standard force used. All three shows portrayed

physical force more than verbal force (27.4%) and nonverbal threats (10.9%), with an

overall distribution of 61.7% physical force portrayal.

17

The use of force and excessive force was examined as separate entities. This was

done to categorize the severity of officers actions; many times throughout the coded

episodes, force was used for a variety of reasons, yet was not considered “excessive” by

the coding standards. Excessive force was recognized as an officer going well outside

what was considered necessary to apprehend, diffuse, restrain, or otherwise interact with

a person of interest. An example of the separation of the use of force and excessive force

is as follows: an officer who is interrogating a suspect begins to use threatening language

in order to extract a confession. This use of force escalates to excessive force when the

officer begins to physically assault the suspect whether out of frustration, to gain

information, or other factors.

Chicago PD stands as an outlier when coding for excessive force, and is worth

examining on why this may be. While the general argument of supplying entertainment

and intensity to a show can be applied, there is some truth rooted in the portrayal of

excessive force at the hands of Chicago police. In 2016, the University of Chicago

organized the Chicago Torture Archive, compiling documents, transcripts, and other

forms of evidence pertaining to the torture of suspects by Chicago police from 1972-

1991, otherwise known as the Burge Case (Lantigua-Williams 2016). Over 100

individuals, predominantly Black men, were tortured in order to gain false confessions,

witness statements, and prevent others from speaking out against the brutality that took

place under the command of Detective and later Commander John Burge. While it is

unsure if the frequent depiction of excessive force in Chicago PD is tied to the dark

history of police brutality in Chicago, the overall perception of violence between officers

18

and suspects is heightened. This can possibly be attributed to the association between

crime, violence, and the city of Chicago (Metz, 2016).

When looking at scenes of excessive force objectively, it can be difficult to

sympathize with the offending officer as they brutalize a suspect. For regular viewers,

however, the anti-hero phenomenon can explain their fascination with protagonists who

frequently resort to violent measures (Schubert 2017). A Chicago PD scene in particular

shows Sgt. Voight beat a suspect with an iron poker and pushed the end of it into his

chest, while a scene from Law and Order: SVU shows Det. Stabler besides a brutalized

and bloodied man he had beaten only minutes before. Their acts are considered

appropriate in the context of the scene: Sgt. Voight is searching for the whereabouts of a

sex trafficker to save a man’s daughter, while Det. Stabler fought with a pedophile to

have a photo of his daughter taken down from a child pornography website. When paired

with the officer’s reasoning, acts of brutality become digestible, and protagonists who

engage in violence become the anti-hero-- their actions or morality are questionable, but

the audience’s established connection to the character and the context of the scene allows

them to accept their actions.

19

Table 3 displays the top three most frequent types of force per show and overall frequency in percentages

While types of force varied amongst each episode, the most common types of

force used were consistent for all three shows. Rough handling, which includes forcing

the POI’s body against a surface and aggressively pushing the POI, was the most

common type with 167 counts (43.3%). Striking, punching, and kicking were also

frequent, with 50 counts (11.1%) throughout each season. Verbal abuse and threats were

recorded at 67 instances (15%), with an additional 26 instances (5.7%) of verbal force.

Officers frequently used objects when employing force, such as rifles (26 counts), cars (3

counts), knives (2 counts), tasers (1 count), and foreign objects such as crowbars (11

counts).

Each show portrayed rough handling more than any other portrayal of force. This

was done through an array of actions, most notably by aggressively moving the POI,

shoving their body against a surface, or pushing the POI into or onto a surface. The action

itself can be intended by the officer to cause harm to the POI in an attempt to intimidate

20

the individual, control the individual, or express the officer’s frustration towards them.

Rough handling, in some instances, can come across as more subtle; the use of rough

handling was often treated as normal arresting procedure, even if harm towards the

suspect is explicitly indicated.

Verbal force, though not as frequent as physical force, played a significant role in

the portrayal of force. In situations where officers could not utilize physical force to

progress through their case, verbal force was found to be just as effective. Verbal threats

and abusive language were second in frequency for each show, followed by general

verbal force. While each use of verbal force—threats, abusive language, and general

force—was used with the intent to cause harm or meet a goal, each category was distinct

in how it was utilized. Abusive language was often used in cases where an officer has a

personal tie to the victim(s) or case itself, with language solely meant to insult, demean,

or intimidate. An example from Law and Order: SVU season 10, episode 2 demonstrates

this:

Det. Stabler: You’re a steaming bag of crap that I would love to shove

down a hole.

POI: I’m not the enemy. I look but don’t touch […] I can’t change who I

am, I was born this way.

Det. Stabler: No one’s born a deviant.

The purpose of this exchange was to intimidate a known pedophile in order to

gain information on a suspect. The character Det. Stabler, the officer involved, is known

in the show to treat pedophiles harshly due to his personal concerns over his own

children. A combination of the intent to retrieve information coupled with the officer’s

personal bias led to Det. Stabler’s use of abusive language towards the POI. Because the

show has established Det. Stabler’s attitude towards pedophiles, his behavior and

21

language are normalized and accepted. This is reinforced by his partner, Det. Benson, not

reprimanding him or acknowledging his language (Law and Order: Special Victims Unit

10.2).

Threats are similar to abusive language in how it is used to extract information or

intimidate a POI. Where abusive language has a more demeaning or aggressive tone,

threats are used with the express and specific purpose of forcing the POI to comply.

Whether this is to provide information or comply with an officer’s demands, it is

considered a useful tool in situations where cooperation is not given freely. Out of the

three shows, Law and Order: SVU had the highest count of threats used, accounting for

16.6% of all force used in the show. General verbal force, the third category of verbal

force, was coded separately from abusive language and threats due to its delivery. Certain

instances of verbal force would occur in which no explicitly degrading or insulting

language was used when interacting with the POI, nor were any explicit threats made to

them. These instances of verbal force still suggested the officer in question intended to

cause harm to some degree that would coerce the POI to comply with the officer, most

commonly through aggressive tone. General verbal force represented 5.7% of uses of

force amongst all three shows, totalling to 20.7% of all portrayals of force when

combined with abusive language and threats.

Of the 285 counts of force, 36 (10.9%) were nonverbal threats, many of which

were conducted with a secondary instrument. Nonverbal threats in this study are regarded

as physical actions that do not directly harm the POI, but suggest the potential for force

used against them. Much like verbal threats, nonverbal threats were used to coerce a POI

to comply with an investigation, usually through intimidation. The frequent use of

22

secondary instruments was included to portray severity, such as with crowbars, live

wires, furniture, and rifles. Rifles were most common (5.6%) to be used alongside a

nonverbal threat due to their constant availability to officers and clear message for the

potential for violence.

The frequency of force portrayed in each show was shown not to be excessive or

overly violent, with rough handling being the most prevalent type of force. Despite not

being considered “excessive” in this study, it is still worth analyzing. Force and

misconduct were at many times hard to distinguish and portrayed as subtle, making it

difficult for the viewer to fully understand exactly what they were witnessing. In many

cases it was easy to determine force was being used, however the exact fashion (such as

pushing, roughly holding on them, shoving against a wall) was done subtly or with less

attention drawn to the action, so as to imply it was a normal procedure and not a violation

of the POI’s civil rights. These types of force were the least likely to receive any

recognition because they are meant to be perceived as not worthy of recognition. This is

significant as it further works to normalize force to the viewer. Just as more excessive or

violent forms of force are portrayed and considered normal, so is subtly incorporating

instances of force into the narrative.

23

Justification

Table 4 displays the three most frequent justifications used per show and overall frequency in percentages

In this study, justification was viewed as equally important to the act of force as it

represents if the action is considered acceptable, as well as the proposed reaction of the

viewer. Justification for the use of force or excessive force is what frames the action

itself, whether in a positive or negative light, and even more so, if an officer is “good” or

“bad” for resorting to force in order to be effective. The portrayal of justification also

demonstrated how the executive team of each show approached the topics of police

violence and use of force. Showrunners are an extension of the product they create, and

the elements they include can be a combination of what they believe viewers want to see

as well as what they believe is appropriate for the scene (Color of Change Hollywood and

The USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center 2020). This further contributes to the framing

of force, and suggests to the viewer what is and is not acceptable.

In each show, justifications were overwhelmingly present and almost always

implied, with an overall justification rate of 93%. For the justification to be implied, the

24

viewer must have been given the tools necessary to understand why an officer would

resort to force. This could have been established over the course of the episode or

moments before the act occurs. Triggers for force could include a noncompliant or hostile

POI, the implication or established knowledge of guilt, interrogating a POI, and evading

arrest. Less frequently was the verbal acknowledgement and justification of force, which

was most common if the use of force was lethal or a job-impacting consequence was

administered. Throughout all three shows, force was verbally acknowledged and justified

2.8% of the time, most commonly in Chicago PD (6.9%). Table 4 displays the top

frequencies of justification amongst all three shows.

Occasionally, there was no justification for force used. In these instances, officers

would use force unprovoked, or when little to no established reason was provided to the

viewer before the act took place. It is most likely that these instances were used for the

viewer’s entertainment but were often framed as acceptable and warranted despite no

reason given. POI’s who received force with no justification were often non-violent or

compliant, but were in some way related to the case-- this alone provided reasoning for

officers to use force. Chicago PD had the highest rate of no justifications given (10.8%),

with all shows having an overall rate of 7%.

The necessity of the use of force was also analyzed for this study. Justification

and necessity are intertwined, as the use of force can be justified through established

factors, yet still be ruled as not necessary. An example of this is during an interaction

between a detective and suspect in Blue Bloods; Det. Reagan approaches a suspect who

he believes is guilty (Blue Bloods 1.17). The victim had served in the military, as did Det.

Reagan, and so he becomes personally involved in the case. When approaching the

25

suspect, Det. Reagan becomes aggressive: he is verbally abusive, hits the suspect, and

shoves him against a wall until other patrol officers come to stop him. Even though it has

been established to the audience that this case has a personal stake for Det. Reagan due to

his military connections, the reactions by surrounding officers by forcibly removing him

and reprimanding him indicate this interaction was not only not justified but not

necessary as well. Overall, most instances of force were portrayed as and perceived to be

justified (77.2%). Table 1 shows Chicago PD portrayed the most unnecessary force

(41%), almost 30% higher than either other show.

Of all the reasons for justification, implied guilt of the POI by the officer was the

most commonly used (20.9%). Implied guilt could mean either the suspicion by an

officer, as well as the demonstrated guilt of the POI that had yet to be proven in a court of

law. Acting off of suspicions of guilt was common throughout all three shows, even when

guilt had not been firmly established to the audience. This theme was reflected in a

conversation between two detectives in Law and Order: SVU:

Det. Tutuola: Sounds like you’ve already decided he’s guilty.

Det. Benson: ‘Cause that’s how it looks.

The conversation does not go beyond this, and the suspect in question is revealed to be

innocent (Law and Order: Special Victims Unit 10.9). Despite being wrong, the intuition

of an officer is rarely questioned by both characters and, as a result, viewers. The second

most common justifying factor is information gathering (15.3%). Many instances of force

occur within an interrogation room or while officers are investigating and interviewing

possible suspects. In these scenarios, it is common for POI’s to resist questioning to

protect themselves or others, resulting in officers using force to extract information.

26

Force use has ranged from verbal threats to physically assaulting the POI in an attempt to

gather information.

POI’s who were hostile (5.6%) or noncompliant (5.1%) were frequent victims of

force, as attitude towards the officers was shown to be an indicator of whether they felt

force was necessary in the moment. Aggressive, aloof, or rude POI’s were often subject

to both physical and verbal force as their attitude was viewed as in relation to their guilt

status. Despite this, POI’s who were compliant or civil (10.2%) still had force used

against them throughout each show. In these cases, compliant POI’s may have already

been established as guilty or determined as such by the officer involved.

Justification often went hand-in-hand with the use of force, serving to validate or

encourage an officer to use force. As a result, force was perceived as understandable,

necessary, and at times, satisfying for the viewer to watch. When a POI was

noncompliant and/or insulting an officer, a resulting assault to the POI was framed as

well-deserved and is meant to be enjoyed by the viewer. Because the viewer is observing

interactions through the lens of the officer, the anticipated perception is for the audience

member to become frustrated with the noncompliant POI as well. This frames the force

used as positive, making the action acceptable to the viewer. Emotions, background

knowledge, and the intuition of officers all play into the justification of the use of force,

allowing both the viewer to accept the force that has been used, and for the show to

perpetuate the normalization of force used against POI’s.

Consequences

The presence of consequences for the use of force was rarely seen while

analyzing each season. Overall, there were 22 (6.6%) consequences for all episodes

27

coded. The three seasons had an overwhelming number of cases with no consequences,

totalling 254 cases (89.1%) in which no consequences were administered for the use of

force, as shown in Table 1. Chicago PD had the highest rate of consequences, with 9.8%

of cases resulting in some form of consequence for the officer(s) involved. Blue Bloods

had the lowest rate of consequences, with 6.5%. When consequences were administered,

the majority were given by either an officer of the same ranking (43.5%) or by a higher-

ranking officer (43.5%). In almost half (47.1%) of the consequences, the offending

officer was given a verbal reprimand for their actions. Only 14.7% of the time were

officer’s jobs directly impacted; this would result in an investigation into the act of force,

the suspension of an officer, or demoting the officer for a short period of time. In every

case in which an officer’s job was impacted, the issue was resolved within one to three

episodes and the officer resumed their duties.

A lack of consequences does not mean the force used was more justifiable or less

damaging than any other. In terms of types of force used, all three shows had relatively

similar results in rates of physical force and verbal force used. However their difference

in consequences demonstrates how force is regarded and portrayed in the show overall.

Blue Bloods, despite having only 6 explicit consequences for force, was shown to have

similar levels of physical force compared to Chicago PD and Law and Order: SVU. Blue

Bloods was also shown to have the lowest rate of unnecessary uses of force. Low rates of

consequences and unnecessary uses of force alone may suggest to viewers that the

officers portrayed are more justified in using force, and that the use of force was an aid in

solving cases. But because this show has similar rates of overall physical force and

various types of force used when compared to Chicago PD and Law and Order: SVU, it

28

can be argued that Blue Bloods frames the use of force in most cases as a necessity to

solving and fighting crime beyond the show’s platform. Even more so, it may suggest

force, being a necessity, is not deserving of consequence unless an officer is grossly

misusing their power.

Guilt, Innocence, & Clearances

The guilt or innocence status of a POI is significant to this study as it establishes

validity to an officer’s use of force. When a POI is confirmed to be guilty, the use of

force against them immediately becomes warranted, suggesting to the viewer they

deserved force or excessive force to be used against them. For 64% of cases, the POI is

determined to be guilty, with 19% percent of cases of force used against a POI who is not

explicitly guilty, but is associated with the guilty person(s). Of all instances of force

analyzed, 39 cases (14%) were against an innocent person, and of the 39 cases only four

of which did the offending officer receive a consequence. Several of the cases in which

the POI was revealed to be innocent, force against them is still justified to the viewers.

This is often seen in the POI evading arrest or questioning, or becoming hostile due to

fear of becoming involved in a crime unrelated to them. Regardless of the POI’s

innocence, their refusal to cooperate despite the clear stress they are under acts as a

justification for force to be used against them. This establishes the narrative that if they

were innocent, they would have nothing to be afraid of and cooperate with officers.

Factors such as illegal immigration, prior convictions, or fear of incarceration can play

into the POI’s attitude, which can hinder the officer’s search for answers.

In cases where an officer received a consequence, 81% of POI’s were discovered

to be guilty. When an officer is reprimanded for using force against what turns out to be a

29

guilty POI, the guilt undermines the consequence and invalidates any warranted criticism

of the officer. In addition to this, it inadvertently criticizes the idea of those against the

use of force, by implying that force was revealed to be necessary. An episode of Chicago

PD exemplifies this idea, in which an officer shot a suspect who she believed attempted

to shoot and kill her patrol partner (Chicago PD 3.21). For the majority of the episode,

she receives public backlash, becomes involved in an investigation into her shooting, and

is suspended from her position. The POI is framed as a victim of police brutality, playing

on current events and mirroring real-life cases of police shootings and brutality. It is

revealed later in the episode the POI had been guilty all along, extinguishing any real

criticisms of police brutality and police involved shootings—both within the context of

the show, as well as real-life events due to its mirroring.

Furthermore, the clearance rate of each season is significant to this study as it

portrays the general efficiency of officers in each police procedural. In Blue Bloods, each

case is solved and the suspect is either shown to be convicted or implied, producing a

100% clearance rate. Law and Order: SVU had solved 95.5% of cases which resulted in a

guilty conviction, and Chicago PD had solved 91.3% of cases. Cases which were not

considered “solved” had only missed a formal conviction; in several cases, the officers

had established the guilty suspect, however due to extraneous circumstances, they never

went to trial. If the coding for clearance rate was solely dependent on if the officer(s)

solved a case, regardless of trial outcome, each season would have a clearance rate of

100%. Should a show have a high rate of the use of force against guilty POI’s, as well as

a high clearance rate, this can establish to viewers that the use of force is at times

necessary in solving a crime, moving forward in a case, or dealing with a suspect.

30

Discussion

Crime dramas would not be nearly as popular or lucrative if they did not portray

law enforcement as dangerous and action-filled, as opposed to the average experience of

an American police officer. As a result, these shows often rely on scripted violence for

entertainment. It can be inferred that the use of force in crime dramas at statistically

higher levels than used by real-world officers contributes to a crime drama’s popularity.

Force, when used, almost always carries a justification. This can be seen when the

suspect is violent, hostile, armed, and a direct danger to the officer and others. Police

procedurals commonly depict a violent suspect giving the protagonist officer no choice

but to react with force. Media portrayals of officers rarely portray them as unnecessarily

violent, unless they exist within the subgenre of the “bad cop” trope. Consistently

portraying the justification of an officer's actions regardless of the demeanor of the

suspect aids in reinforcing the idea that police officers are constantly putting themselves

in some form of danger in exchange of keeping their city safe, thus serving to justify the

use of force. Rarely was force found not to be justified; in the case where it wasn’t,

lasting consequences were uncommon.

Despite historical and modern accounts of the connection between race and police

brutality, fictional crime dramas rarely address this connection or portray it (Alexander

2010). As noted from the content analysis, officers utilizing force and those receiving it

were both predominantly white men. Although young men of color, especially Black

men, are significantly more likely to be victimized by police brutality, this is not

accurately depicted (Edwards, Lee, and Esposito 2019). The Color of Change et al.

31

(2020) report notes this can be a result of several factors, beginning with the writers

room. Fictionalized crime dramas are predominantly written, directed, and produced by

white men, and inevitably their perspectives on law enforcement as white men bleed into

their storytelling. Of the shows analyzed in this study, Blue Bloods had all white writers

during their 2019 season. Law and Order: Special Victims Unit was found to have over

90% of white writers, of which 70% of which were male (Color of Change et al. 2020).

Chicago PD was found to have approximately 90% of white writers for the same season.

Not accurately portraying the systemic racism in law enforcement that impacts

people of color creates a reality in each show in which people of color do not experience

racism within the criminal justice system (Color of Change et al. 2020). While this can be

seen as hopeful towards an equal justice system, it suggests that the predominantly white

showrunners avoid the topic in general as it can create controversy. Instead, occasional

episodes focus on these topics in an effort to appear relevant. These episodes often

invalidate genuine critique of police use of force, framing those seeking accountability as

an adversary to law enforcement. Fictional officers who use force are framed as guilty,

only to be proven right by the end of the episode. This narrative further emphasizes force

is justified no matter how excessive when used by law enforcement. By producing topical

episodes, these shows are choosing to engage in the conversation of police accountability

and brutality. These episodes ultimately perpetuates the idea that force is a necessary

component of police work, while simultaneously disregarding systemic racism in law

enforcement and invalidating the experiences of the people of color who have had

negative experiences with police officers.

32

Officers in crime dramas frequently act on gut instincts and assume guilt before it

has been established, whether to the officer or to the viewer. This can be problematic as

each show demonstrates that officers who act on their gut and assume guilt end up being

right in the end, establishing trust between the officer and the viewer that the officer’s

intuition is rarely wrong. When an officer uses force against an innocent suspect, the

issue is often glossed over and not acknowledged—essentially brushing the officers

misjudgement under the rug. When shows have high instances of officers using implied

guilt to use force against what turns out to be a guilty suspect, as well as high clearance

rates, this suggests to viewers force is necessary in solving cases or moving forward in

them. In addition, it suggests high clearance rates are partially due to officers using force

in order to be more efficient in solving a case. The lack of consequences despite the

acknowledgement of an officers use of force as well as success in solving cases serves to

normalize police violence and the use of force as an everyday facet of the job.

Conclusion

Crime dramas and their many sub-genres are made to entertain its viewers, taking

professions, themes and events that are based on reality and dramatizing them for

entertainment. However, its origin and the ideas used are the closest to reality crime

dramas come to. The criminal justice system is often over exaggerated and incorrectly

depicted in crime dramas for the sake of entertainment. Violence used for entertainment

has shown to increase a show’s popularity—or, not significant enough of a deterrent from

watching. Force and brutality were found to be frequent, almost always accompanied by

a justification to make an officer’s actions excusable. Ultimately, the message this sends

to viewers is an officer’s intuition is rarely wrong, and when they choose to use force to

33

any degree, the viewer should trust that these actions will lead to a case being solved.

Though this study can only go as far as to analyze how force is portrayed and justified, it

is clear through additional research and literature that the normalization and justification

of force does not remain within the bounds of entertainment, and has the ability to impact

its viewers.

Limitations

A major limitation of this research is that it is only a content analysis, and as such

only the portrayal of the use of force and excessive force could be studied. If a

quantitative methodology such as surveying viewers was included alongside the content

analysis, the explicit analysis of how crime dramas and entertainment media impact

viewer’s opinions on the use of force could be provided. As a result of this limitation, I

am only able to form conclusions based on past, separate research and literature as well

as my own results. In addition to this, I can only speculate what the impact of the

justification of force and normalization of violence is, instead of drawing conclusions

based on specific survey responses aligned with analysis findings.

A second limitation of this research is the variety of media coded. While crime

dramas have proven to be popular, they have also shown to have the least significant

impact on attitudes toward law enforcement and its many facets to viewers. Compared to

newsroom media and reality-based crime dramas, viewers can distinguish crime dramas

and their portrayals as fictionalized, and in most cases, do not accept crime drama

portrayals as immediate fact. Newsroom media and reality-based crime dramas, however,

are considered by viewers to be more realistic and accurate in their portrayals, as they are

not scripted shows. As the analysis of crime news media is already a popular area of

34

research, it would be worthwhile to study reality-based crime dramas alongside

entertainment media. If a reality-based show such as COPS or Live PD were included in

the research, a broader perspective of the crime drama genre would have been achieved.

Possible Solutions

It is unrealistic for these shows to be taken off the air, as they are extremely

popular with large fanbases. If any change in how force is portrayed is to happen, it must

begin behind the scenes. Popular police procedurals are predominantly written, directed,

and produced by white men, which some authors have concluded is a significant factor

into why force is so often portrayed as necessary and justified (Color of Change et al.

2020). By incorporating significantly more diversity behind the scenes at a consistent

rate, it is possible to change how narratives are written and framed. Furthermore, many

police procedurals include an officer on site to consult regarding the accuracy in

portraying law enforcement. However, there is rarely, if ever, an advocate for victims of

police brutality or otherwise holding a social position opposite to that of police to offer

counter-perspectives (Metz 2020). Introducing more voices to provide the victim’s

perspective may change in how the viewer perceives the situation in which force was

used, and potentially sympathize with the victim rather than the officer.

Future Research

Future research should continue to focus on the portrayal of force in other police

procedurals, crime dramas, and crime-related entertainment media. Similar to Donovan

and Klahm’s (2015) study, qualitative studies should be conducted alongside content

analysis to examine how frequent crime drama viewers are impacted by the shows they

watch, with a specific focus on the use of force and violence. As mentioned previously,

35

including reality-based crime dramas or conducting research solely focusing on reality-

based crime dramas would also contribute significantly in examining how the portrayal of

force impacts viewers. Reality-based crime dramas have been shown to have a greater

impact on overall attitudes towards law enforcement and beliefs regarding the use of

force amongst viewers due to its perceived realism. Adding to the literature on this topic

would help to further understand the many aspects of reality-based crime dramas and

how consumers are impacted by overall viewership. Furthermore, similar to the Color of

Change et al. (2020) study, future research should pay attention to the production team of

each show, such as the racial and gender makeup of writers, directors, and producers.

36

RESOURCES

Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of

Colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press.

Arntfield, Michael. 2011. “TVPD: The Generational Diegetics of the Police Procedural on

American Television.” Canadian Review of American Studies, 41(1):75-95.

Boivin, Rémi, Annie Gendron, Camille Faubert, and Bruno Poulin. 2017. “The Malleability of

Attitudes toward the Police: Immediate Effects of the Viewing of Police Use of Force

Videos.” Police Practice & Research, 18(4):366–75.

Briggs, Steven J, Nicole E. Rader, and Gayle Rhineberger-Dunn. 2017. “The CSI Effect, DNA

Discourse, and Popular Crime Dramas.” Social Science Quarterly, 98(2):532-546.

Brown, Darrin, Sharon Lauricella, Aziz Douai, and Arshia Zaidi. 2012. “Consuming Television

Crime Drama: A Uses and Gratifications Approach.” American Communication Journal,

14(1):47-60.

Callanan, Valeria, and Jared S. Rosenberger. 2011. “Media and Public Perceptions of the Police:

Examining the Impact of Race and Personal Experience.” Policing & Society, 21:2, 167-

189.

Coenen, Lennert, and Jan Van den Bulck. 2016. “Cultivating the Opinionated: The Need to

Evaluate Moderates the Relationship Between Crime Drama Viewing and Scary World

Evaluations.” Human Communication Research, 42(3):421–440.

Color of Change Hollywood and The USC Annenberg Norman Lear Center. 2020. Normalizing

Injustice: The Dangerous Misrepresentations That Define Television’s Scripted Crime

Drama. Retrieved from https://hollywood.colorofchange.org/wp-

content/uploads/2020/02/Normalizing-Injustice_Complete-Report-2.pdf

Cooke, Louise, and Paul Sturges. 2009. “Police and Media Relations in an Era of Freedom of

Information.” Policing & Society, 19(4):406–24.

Donovan, Kathleen M., and Charles F. Klahm IV. 2015. “The Role of Entertainment Media in

Perceptions of Police Use of Force.” Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(12):1261-1281

Dowler, Kenneth, and Valerie Zawilski. 2007. “Public Perceptions of Police Misconduct and

Discrimination: Examining the Impact of Media Consumption.” Journal of Criminal

Justice, 35(2):193–203.

Edwards, Frank, Hedwig Lee, and Michael Esposito. 2019. “Risk of Being Killed by Police Use

of Force in the United States by Age, Race-Ethnicity, and Sex.” Proceedings of the

National Academy of Science of the United States of America, edited by J. Hagen.

Evanston: IL. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821204116

37

Habermas, Jurgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a

Category of Bourgeois Society. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

FBI. 2016. Crime in the United States 2015. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Gallagher, Brenden. 2018. “Just Say No to Viral ‘Copaganda’ Videos”. The Daily Dot. Retrieved

September 23, 2018 (https://www.dailydot.com/irl/cop-viral-videos/).

Kappelere, Victor E., and Gary W. Potter. 2018. “Battered and Blue Crime Fighters: Myths and

Misconceptions of Police Work.” Pp. 271-312 in The Mythology of Crime and Criminal

Justice. 5

th

ed. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Lantigua-Williams, Juleyka. 2016. “A Digital Archive Documents Two Decades of Torture by

Chicago Police.” The Atlantic, October 26th.

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/10/10000-files-on-chicago-police-

torture-decades-now-online/504233/

Masur, Jonathan and McAdams, Richard H. (2019) "Police Violence in The Wire." University of

Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2018 , Article 7.

Mawby, Rob C. 2010. “Chibnall Revisited: Crime Reporters, the Police and ‘Law-and-Order

News’.” British Journal of Criminology, 50(6):1060-1076.

Metz, Nina. 2016. “How T.V. Shows Like ‘Chicago P.D.’ Portray Chicago Gun Violence.”

Chicago Tribune, November 16th. https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/ct-

violence-television-ae-1113-20161116-story.html

Metz, Nina. 2020. “Do Cop Shows Like ‘Chicago P.D.’ Reinforce Misperceptions About Race

and Criminal Justice? A New Study Says Yes.” Herald & Review, February 16th.

https://herald-review.com/entertainment/television/do-cop-shows-like-chicago-p-d-

reinforce-misperceptions-about-race-and-criminal-justice-a/article_a0674b03-bba0-50c9-

9a1f-a825f678ce14.html

Rantatalo, Oscar. 2016. “Media Representations and Police Officers’ Identity Work in a

Specialised Police Tactical Unit.” Policing & Society, 26(1):97–113.

Sargent, Andrew. 2012. “Police in Television.” Pp. 1767-1774. The Social History of Crime and

Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia, edited by W. R. Miller. Washington, D.C.:

SAGE Publications.

Schubert, Christoph. 2017. “Constructing the Antihero: Linguistic Characterisation in Current

American Television Series.” Journal of Literary Semantics, 46(1):25–46.

TV Guide. 2020a. “Law and Order: Special Victims Unit.” Retrieved Sept. 10th, 2020.

https://www.tvguide.com/tvshows/law-order-special-victims-unit/100257/

38

TV Guide. 2020b. “Blue Bloods.” Retrieved Sept 10th, 2020.

https://www.tvguide.com/tvshows/blue-bloods/303333/

TV Guide. 2020c. “Chicago PD.” Retrieved Sept 10th, 2020.

https://www.tvguide.com/tvshows/chicago-p-d/556344/

TV Series Finale. 2020a. “Law and Order: Special Victims Unit.” Retrieved Sept. 10th, 2020.

https://tvseriesfinale.com/tv-show/law-order-special-victims-unit/

TV Series Finale. 2020b. “Blue Bloods.” Retrieved Sept 10th, 2020. https://tvseriesfinale.com/tv-

show/blue-bloods/

TV Series Finale. 2020c. “Chicago PD.” Retrieved Sept 10th, 2020. https://tvseriesfinale.com/tv-

show/chicago-pd/

Van den Bulck, Jan, Astrid Dirikx, and Dave Gelders. 2013. “Adolescent Perceptions of the

Performance and Fairness of the Police: Examining the Impact of Television Exposure.”

Mass Communication & Society, 16(1):109-132.