Messiah University Messiah University

Mosaic Mosaic

Graduate Education Student Scholarship Education

2018

Exploration of Positive Teacher-Student Relationships in the Exploration of Positive Teacher-Student Relationships in the

Online Context of VIPKID Online Context of VIPKID

Elise R. McClelland

Messiah College

www.Messiah.edu One University Ave. | Mechanicsburg PA 17055

Follow this and additional works at: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/gredu_st

Part of the Online and Distance Education Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of

Education Commons

Permanent URL: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/gredu_st/14

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

McClelland, Elise R., "Exploration of Positive Teacher-Student Relationships in the Online Context of

VIPKID" (2018).

Graduate Education Student Scholarship

. 14.

https://mosaic.messiah.edu/gredu_st/14

Sharpening Intellect | Deepening Christian Faith | Inspiring Action

Messiah University is a Christian university of the liberal and applied arts and sciences. Our mission is to educate

men and women toward maturity of intellect, character and Christian faith in preparation for lives of service,

leadership and reconciliation in church and society.

Running head: EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

Exploration of Positive Teacher-Student Relationships in the Online Context of VIPKID

Elise R. McClelland

Messiah College

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

2

Abstract

In this paper, I explore how VIPKid teachers build positive relationships with students in their

unique online context. I began by establishing the need, importance, and nature of positive

teacher-student relationships. I included the results of a survey given to 36 VIPKid teachers in

order to better understand the perspective of these teachers on positive relationships with

students, what barriers these teachers face in building relationships, and what techniques they

employ to build relationships. I found that the results imply that in order to build better

relationships with students, VIPKid teachers must communicate care for their students despite

barriers they may face.

Keywords: teachers-student relationships, online

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

3

Table of Contents

Page

Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………2

Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………………………....3

Chapter I: Introduction………………………....………………………………………………….6

Purpose of the study.............................................................................................................7

Research questions...............................................................................................................7

Chapter II: Literature Review…………………………………………………………..………....8

The nature and importance of teacher-student relationships…………….………………..8

Variables affecting teacher-student relationships………………………………………....9

Context……………………………………………………………………………9

In the mainstream K-12 classroom…….……………………………….....9

In the ESL classroom.…………….…………………………………..….10

In the online classroom……..……………………………………………11

Environment……………………..……………………………………………… 12

Culture and language.............................................................................................12

Perception………..……………………………………………………………....13

Application in the VIPKid classroom……………...…………………………….14

Conclusion……………...………………………………………………………………..16

Chapter III: Methodology………………………………………………………..........................17

Research Design………………………………………………………….........................17

Participants…………………………………………………………….............................17

Data Collection and Analysis……………………………………….................................18

Chapter IV: Findings……………………………………………………….................................21

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

4

Introduction…………………………………………………………................................21

Barriers………………………………………………………….......................................21

Barriers of Time……………………………………….........................................22

Barriers of Distance…………………………………...........................................23

Barriers of Language and Culture…………………..............................................24

Teacher Techniques and Actions…………………………………...................................25

Names....................................................................................................................25

Props and rewards..................................................................................................25

Feedback................................................................................................................26

Safe and Welcoming Environment………………………....................................26

Encouragement and Support………………………………..................................27

Humor and Laughter………………………………………..................................28

Results and Benefits…………………………………………………...............................28

Comfort and Trust…………………………………………..................................29

Confidence and Security….………………………………...................................29

Risk-taking and Mistake-Making…………………………..................................29

Trained or Untrained……………………………………………......................................30

Chapter V: Implications of the Study……………………………….……..................................31

Overcoming Barriers………………………………………………..................................31

Applying Techniques…………………………………………….....................................32

Working Toward Results…………………………………………...................................33

Chapter VI: Conclusion....................................…………………………….................................34

Limitations of the study.....................................................................................................34

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

5

Future Recommendations………....………………………………..................................34

Summary…….................................................................................................……...........36

References………………………………………………………………......................................37

Appendix A……………………………………………………………………............................42

Appendix B....................................................................................................................................44

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

6

Exploration of ESL Teacher Techniques in Building Positive Relationships with Students in the

Online Context of VIPKID

Chapter I: Introduction

Through the use of technology, I am able to be an English as a Foreign Language (EFL)

teacher to children in China with the online educational company VIPKid. When I began

working with VIPKid in early 2016, I was one of less than 1,000 teachers. As of early 2018,

VIPKID has “more than 30,000 teachers and over 200,000 paying students” (Conboye, 2018).

Indeed, “VIPKid has seen explosive growth as Chinese parents seek out high-quality education

for their children, particularly in English” (Bloomberg News, 2017). I have witnessed much of

that growth in my own time with VIPKid.

Over these two years, I have had the privilege of teaching English to hundreds of Chinese

students ages 4 to 12 years old. The classroom is set up to allow maximum engagement in a

virtual setting (see Appendix B). The student and teacher are able to see and speak to one another

through live video feed. They are also able to communicate by typing in a chat box. The lessons

are taught through interactive slides on which the student and teacher can draw to interact with

the slides. The students watch videos and participate in activities and quizzes before class in

order to prepare. This flipped classroom model enables the student and teacher to focus on the

application of language skills during each 25-minute class session. The focus of these lessons is

to reinforce content learning, to clarify areas of confusion, and to allow students opportunities to

practice listening, speaking, reading, and writing English. The student-teacher interaction is an

important aspect of the learning model with VIPKid. While information about the language may

be transferred through videos and activities before class, the teacher is responsible “to stimulate,

to engage, to involve, to facilitate, and to be there as a resource” (Tomlinson, 2016, p. 105). The

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

7

one-on-one context allows students to apply their language learning in conversation while

receiving undivided attention, targeted guidance, and constructive feedback from their teacher.

Because the VIPKid is designed to be a one-on-one learning context, I wanted to explore

the techniques teachers use to build relationships with their students. I also wanted to discover

what barriers prevented teachers from feeling positively connected with their students. While

there is an abundance of research on teacher-student relationships, VIPKid is a new educational

platform that brings unique challenges and considerations to this area of research.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to gather teachers’ opinions about positive student-teacher

relationships and to explore their efforts to build these relationships with their students in the

online educational context of VIPKid.

Research Questions

1. How do teachers build positive relationships with students in the online EFL context

of VIPKID?

1.1. What barriers do teachers encounter when building positive relationships with

students in this context?

1.2. What techniques or methods do teachers use to overcome these barriers and build

relationships with their students?

1.3. What are the perceived results or benefits for teachers and students who have

positive relationships?

1.4. Do TESOL-trained teachers view relationship building with students differently

than teachers who are untrained?

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

8

Chapter II: Literature Review

The Nature and Importance of Teacher-Student Relationships

From the introduction to formal education in kindergarten to the culmination at high

school graduation, positive relationships between teachers and students can have the far-

reaching, long-lasting benefit of directly and propitiously impacting student achievement in

grades K-12. One study (Hamre & Pianta, 2001) found that “early teacher-child relationships, as

experienced and described in kindergarten by teachers, are unique predictors of academic and

behavioral outcomes in early elementary school, with mediated effects through the eighth grade”

(p.634). Research also showed that positive teacher-student relationships could be a safeguard

against drop out, could impact student motivation and attitude toward learning, and could

influence student success in academics (Bernstein-Yamashiro & Noam, 2013). The antithesis

was also true with poor or conflictual teacher-student relationships negatively impacting student

engagement, academic achievement, and peer socialization (Hughes, 2011). Positive teacher-

student relationships can also benefit the teacher as they can provide motivation and energy to

invest more meaningfully in the success of the student (Hamre & Pianta, 2001). These

relationships can “inspire teachers’ work and give them a deep sense of purpose” (Bernstein-

Yamashiro & Noam, 2013, p. 46). These relationships both “drive and define the meaning of

teachers’ work and can be pivotal to student success” (Bernstein-Yamashiro & Noam, 2013,

p.46).

A positive teacher-student relationship is a caring relationship. The teacher cares about

the students’ well-being not only academically, but also emotionally, socially, physically, and

spiritually. The teacher is warm and welcoming, gives respect and support, and communicates

empathy and understanding. Teacher-student relationships are critically important to the success

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

9

of learners. The development of these positive relationships should be prioritized as an integral

part of educational endeavors. In this review, the author will explore teacher-student

relationships in different educational contexts in order to better understand the practices of

teachers in the specific context of VIPKID.

Variables affecting Teacher-Student Relationships

Context. For the purposes of this paper, the word context encompasses several factors.

Context not only refers to the pedagogical setting in which the teacher and student meet together,

but may also influence the educational objectives, mode of lesson delivery, or duration of class

time. Others considerations would be the age of the learners, their language level, or their

purpose for studying English. Because VIPKid teachers work with children, we will not consider

adult educational contexts in the scope of this paper.

In the mainstream K-12 classroom. The task of building positive teacher-student

relationships in the traditional classroom setting offers both challenges and rewards. Establishing

relationships in the classroom can be difficult. Because “both teachers and students navigate

complex networks of relationships constrained by rigid schedules, high student-teacher ratios,

curriculum mandates, and testing practices” (Stewart, 2016, p. 23), teachers may struggle to

connect and nurture relationships with each student. With the focus on standards and high-stakes

testing, teachers feel they spend too much time preparing students (Center on Education Policy,

2016) which can add pressure and stress to both teacher and student. One must also consider the

personal, affective influences such as personality, circumstances, or conflicts that may also act as

hindrances in building relationships. Nel Noddings (2005) encourages teachers to consider the

“real, pressing needs” of their students such as “homelessness, poverty, toothaches, faulty vision,

violence, fear of rebuke or mockery, sick or missing parents, feelings of worthlessness” (p.151).

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

10

These needs may must be considered in order to facilitate both learning in the classroom and

positive relationships.

Challenges exist in this context, but traditional classroom teachers also have advantages

to creating positive relationships. Interacting with students for extended periods of time, knowing

their students’ histories and educational backgrounds, and being acquainted with the family of

their students can all aid the teacher as foundations on which to build relationships. These factors

can also help the teacher to better understand and meet the needs of the student which can

contribute to a more positive relationship. Teachers in this setting may also connect with students

through extracurricular activities such as clubs or sporting events.

In the ESL classroom. The ESL classroom presents new challenges to overcome in

addition to those experienced the mainstream ESL classroom setting. English language learners

and their teachers are most likely “separated by a chasm of cultural, linguistic, experiential, and

socioeconomic differences” (Stewart, 2016, p.22). These differences may make the building of

positive teacher-student relationships more difficult, but the importance of the task should not be

diminished because “the existence of positive relationships inside the classroom is considered as

possibly one of the most influential factors in language learning (Sánchez, González, &

Martínez, 2013, p. 117).

Stephen Krashen’s hypothesis on second language acquisition, The Affective Filter

Hypothesis (Krashen, 1982), states that the affective variables of motivation, self-confidence,

and anxiety can negatively influence a student’s ability to acquire a second language. Therefore,

the ESL teacher must strive to build positive relationships with the students in order to create a

low-anxiety learning environment in which the student is able to build confidence and

motivation. When teachers and students have positive relationships, the affective filter is more

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

11

likely to be lower because students understand that their teachers care about their well-being and

success.

Positive student-teacher relationships can also help motivate English language learners.

According to one study (Yunus, Osman, & Ishak, 2011), ESL students show more classroom

engagement and focus despite boring or difficult language input when they have a high-quality

relationship with their teacher. Research (Jiménez & Rose, 2010) also suggests that meaningful

teacher-student relationships in the ESL classroom can improve the quality of instruction.

Teachers in ESL classrooms should strive to “learn more about students, about their

communities, and about their cultural and linguistic backgrounds” (Jiménez & Rose, 2010,

p.406).

In the online classroom. In the modern, technological era, education can and does take

place over the internet. Students and teachers are able to connect and interact in virtual

classrooms. This virtual interaction can add yet another dynamic to building positive teacher-

student relationships.

Although students and teachers in online classrooms do not have the advantage of

meeting regularly in person, these settings offer multiple venues in which to interact and

communicate. Teachers and students may use discussion boards, videos, e-mail, and assignments

to interact. In this setting, both the quantity and quality of the interactions matter (Zelihic, 2015).

Teachers can increase the quality of interactions in this context by creating opportunity for social

and personal exchange, being available to respond to student needs and questions, and giving

timely, appropriate feedback which can aid the understanding and academic development of the

student (Bruster, 2015; Leibold & Schwarz, 2015).

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

12

Environment. Environment is distinguished from context in that it refers to more than

the logistics of the teaching situation. A class environment is a “relational and behavioral

climate” (Bernstein-Yamashiro & Noam, 2013, p.20) that is conducive to building positive

relationships. “A climate in which caring relations can flourish should be a goal for all teachers

and educational policymakers” (Noddings, 2012, p. 777) because first and foremost students are

people with needs and emotions that must be addressed. Students who feel safe, cared for, and

connected to teachers do better academically, socially, and emotionally in school (Bernstein-

Yamashiro & Noam, 2013; Hughes, 2011; Hughes & Wu, 2012). Regardless of context, teachers

should work to make their classrooms environments in which students are comfortable,

respected, and valued. Teachers are responsible to ensure that interactions in the classroom

“foster relationships and create a safe space for holistic development” (Ogilvie & Fuller, 2016,

pp.91).

Culture and Language. Educators in today’s world must be interculturally competent

and multiculturally aware. They should seek to understand how culture can influence their

students’ perspectives on learning. Teachers must also learn to “recognize that each of their

cultural perspectives is one of many that are legitimate” in order to “create an inclusive

classroom environment where cultural differences are an asset to the learning community and

each individual” (Medina-López-Portillo, 2014, p. 334). In any context, teachers may have the

privilege of engaging students whose culture is different from their own. Teachers must

recognize and respect how those differences can influence student learning and relationships.

However, this multicultural understanding is particularly vital and foundational to teachers of

English language learners.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

13

In her book Language and Culture (1998), Claire Kramsch explains that language and

culture are intimately connected in three ways: language expresses cultural reality, language

embodies cultural reality, and language symbolizes cultural reality (p. 3). Therefore, our culture

influences not only how we use and understand language, but also how we make sense of the

world. Even if two people from different cultures are speaking the same language, there may still

be miscommunication and misunderstanding due to cultural expectations. For example, while an

American speaking Chinese may feel the need to say “thank you” as a marker of politeness or

gratitude, native Chinese speakers may interpret this phrase as signifying social distance and

unnecessary formality (Fallows, 2015). The culture influences the use and interpretation of the

words. When seeking to build relationships with students with a different cultural and linguistic

background, it is important to remember that culture influences how they interpret words and

actions.

Educational norms around the world are different as well. For example, while students in

the United States may expect a level of familiarity or even friendship with their teachers, Chinese

students may view teachers with more distance and reverence which “reflects a respect for

hierarchy and authority” (Wang & Du, 2014, p. 448). A Chinese student and an American

teacher may have a different interpretation of what constitutes positive relationships based on

cultural assumptions. Teachers must be aware and sensitive to the cultural influences when

seeking to building positive relationships with students in cross-cultural settings.

Perception. In light of the context, environment, and culture teachers and students may

experience the same relationship, but interpret it differently (Lewis, 2001). This difference in

perception is important because our perception influences our experiences and reality. Teachers

must “learn how to communicate in such a manner that students will perceive that he or she cares

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

14

about them” (McCrosky, 1992 as cited in Teven and McCroskey, 1996, p. 1). Student perception

plays a vital role in the development of teacher-student relationships. Students notice both verbal

and nonverbal communication cues from teachers that influence their perception of how the

teacher cares for them. In order for students to have a positive perception, teachers need to

communicate “empathy, understanding, and responsiveness” (McCrosky, 1992 as cited in Teven

and McCrosky, 1996, p. 2). Teachers can practice the communication of caring to enhance the

perception of positive relationships even if they are unable to deeply connect with each and

every student.

Applications in the VIPKid Classroom. The VIPKid classroom remains a unique

educational setting. As in the ESL classroom, the educational goals include the learning of

English language skills in reading, writing, listening, and speaking. There are also content

objectives in math, science, and social studies based on U.S. Common Core standards as one

would find in the mainstream K-12 classroom setting. This means that the students, particularly

in higher proficiency levels, are “not only learning English as a subject but are learning through

it as well” (Gibbons, 2003, p. 247). The main goal, however, is to learn to use English to speak

about these other topics.

VIPKid uses a flipped classroom model so that “classroom time can be used for engaging

in activities, discussing concepts, clarifying hard-to-understand information, and investigating

questions related to content” (Basal, 2015, p. 29). This model facilitates student-centered class

time in which teachers can focus on the needs of the student. If a student is prepared for class and

is capable of completing the lesson in less than the allotted 25 minutes, teachers can encourage

discussion, play games, or ask questions about the student’s life. These activities can give the

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

15

student opportunities to practice conversation skills while also allowing the teacher to make

better personal connections.

Unlike some online educational contexts, live video feed of both teacher and student

during class allow for better interaction. Teachers are able to use props, pictures and physical

movements to help create meaning and share experiences. These visual aids can be used to both

teach content objectives and help create connections with the students (Strickland, Keat, &

Marinak 2010). The chat box feature also helps teachers to provide text to as visual scaffolding

during lessons.

The linguistic and cultural barriers present in this context as well as the mode of distance

learning are obvious impediments to building relationships with students. VIPKid teachers must

find ways to engage and connect with students despite these barriers. Creating a classroom

environment that in which the teacher is focused, patient, and intentional with teaching and

feedback is one way to overcome such barriers. Teachers can also affect a student’s perception

by using non-verbal cues such as smiling and gesturing.

Another variable in the VIPKid context is the issue of time. Each class is only 25-minutes

long, so meeting lesson objectives while also working through the language barrier in this short

time can be a hindrance to connecting with students. Students are also not always guaranteed the

same teacher for every class. Teachers open available slots in their schedules and students’

parents book the slots. Depending on the demand for the teacher, her spots may fill quickly

before students are able to book reoccurring classes. This lack of guaranteed consistency can be a

hindrance to building relationships with students as well. However, even if a teacher only meets

with a student once for 25 minutes, she can still practice verbal and non-verbal cues that

encourage the student to perceive caring even if no real relationship is formed. This skill is much

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

16

needed in this context because students’ parents can leave public ratings and feedback about the

teacher. If a teacher is unable to communicate care and positivity, they may receive a poor

review which can affect their booking rates. Recently, VIPKid has allowed teachers to request

reviews of poor ratings. If the teacher achieved the educational objectives, then the rating seems

unfairly given, then it can be invalidated. This new policy helps relieve some pressure for

teachers as they have the freedom to teach without worrying about negative opinions of parents.

Conclusion

Given the importance of positive teacher-student relationships in other educational

contexts, I wanted to explore them in the specific context of VIPKid. While there is an

abundance of research on teacher-student relationships in the traditional classroom, the ESL

classroom, or the online classroom, for the online ESL context, there is a dearth in research. The

proposed research from this study would help to decrease that deficit by exploring the techniques

and methods teachers with VIPKid use to build relationships with their students in a one-on-one,

ESL, virtual classroom context. For the sake of the more than 30,000 teachers and 200,000

students at VIPKid, researching positive teacher-student relationships in this specific context is a

worthwhile pursuit.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

17

Chapter III: Methodology

Research Design

Because the focus of this study was on exploring and understanding the relational

experiences of VIPKid teachers, I employed a qualitative research method. Qualitative research

is conducted to gather participants’ views and experiences in order to better understand a central

phenomenon (Creswell, 2015). There were many factors contributing to the building of positive

teacher-student relationships and “qualitative research is salient for the understanding of

personal, relational, group, organizational, cultural, and virtual contexts in a range of different

ways” (Tracy, 2013, p.8). The constructivist approach of grounded theory influenced the

research because I wanted to focus on the perceptions and “meanings ascribed by the

participants” (Creswell, 2015, p.432). Specifically, I was curious about teachers’ beliefs about

teacher-student relationships and how those views are applied when working to build positive

relationships with their students. The survey conducted for this study focused on VIPKid

teachers’ perceptions of positive relationships they have with their students. Teacher participants

shared experiences of positive relationships including techniques used to build these

relationships and barriers that hinder these relationships from forming. They were also asked to

share the duration of employment with VIPKid as well as their TESOL qualifications in order to

better understand how these qualifications may or may not influence perspectives.

Participants

The participants in this study were teachers who had been teaching for at least 6 months

with VIPKid. The sampling was purposeful and homogenous because I intentionally recruited

participants “based on membership in a subgroup that has defining characteristics” (Creswell,

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

18

2015, p. 207). I chose the defining characteristics of VIPKid teachers who had completed at least

one, six-month contract because I wanted to learn from participants with adequate experience in

building relationships with students in this context.

As a VIPKid teacher, I have access to online VIPKid teacher communities. In a private

Facebook group and on a private discussion board, I obtained permission from administrators to

request participants for this study. After exemption approval from the Institutional Review Board

at Messiah College, I posted a request in both of these groups for teachers who had completed

more than one six-month contract. Initially, 37 teachers responded to the survey. However, I

chose to use only 36 survey responses for this study because one participant chose to skip

questions I felt were important to the overall study. Each respondent had at least 6 months

experience with VIPKid, but some had 2 or more years. Of the 36 participants, 18 had TESOL

qualifications of some variety and 18 had none. For the purposes of this paper, participants are

referenced by their survey response number.

Data Collection and Analysis

Using a link from SurveyMonkey, the volunteers completed a ten-question survey (see

Appendix A). On the SurveyMonkey website, I was able to review the response results. I printed

the chosen 36 responses so that I could begin “primary-cycle coding” (Tracy, 2013, p.189).

Tracy (2013) describes coding as “the active process of identifying data as belonging to, or

representing, some type of phenomenon” (p.189). In this initial phase, I read through all of the

responses to gain a general understanding of the information. It was during this reading I realized

that one of the participants had skipped questions and I chose not to include these responses in

my study. On the second read through, I used different colored highlighters to mark recurring

words. I wrote broad, descriptive terms in the margins to begin assigning codes. After

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

19

completing the initial reading and coding with paper and pen, I used the search function in

Microsoft Word to digitally search for all occurrences of the selected code words. By utilizing

this function, I found that some words I initially thought may be important did not occur enough

to be significant. Other words were used repetitively amongst participants to convey the same

meaning and therefore represented a recurring theme throughout the data. I organized these

significant codes in a second Word document including the code word, the participant number,

the exact quote, and the question number from the survey. I read through these words and quotes

and used them as the foundation on which to expand the words to broader themes. For example,

interests was a recurring theme, but not every teacher used this word specifically in their

responses. Some described connecting with their students by asking about their favorite toys or

books, but because they were using their students’ interests as a means to build relationships, I

included such descriptions under the code word interests.

At this point in the analysis, I reviewed my research questions to ensure that the data

emerging from the responses and the existing research questions were corresponding. As Tracy

(2013) suggests, “throughout the analysis, revisiting research questions and other sensitizing

concepts helps you to ensure they are still relevant and interesting” (p. 191). Upon revisiting

these questions in light of the data, I found that many teachers spoke of benefits of having

positive teacher-student relationships. I did not originally have a research question dedicated to

this topic, however, I decided to add another question in order to allow me to explore the

perceived benefits and results that teachers mentioned in their responses.

After completing the coding phrases, I then organized categories based on these recurring

elements in order to have a better, broad understanding of the views, values, and actions of

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

20

VIPKid teachers. I used these categories to explore, organize, and write about the findings of this

study.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

21

Chapter IV: Findings

Given the importance of positive teacher-student relationships in other educational

contexts, I was curious to better understand the development of these relationships in the

relatively new and unique context of VIPKid. As a starting point, I asked if teachers thought

relationships with their students were important and asked them to explain why or why not.

Unanimously in this survey, 100% of participants agreed that positive teacher-student

relationships were important in the context of VIPKid. Some considered positive relationships as

necessary to facilitate learning. Others thought of them as an enhancement, encouragement, or

motivation for learning better. A few mentioned that positive relationship building was important

for teachers to build up and retain a student base. I also asked if teachers thought positive

relationships enhanced their teaching as well as the students’ learning. Once again, 100% of

teachers affirmed their beliefs that positive relationships with their students do influence both

their teaching and the student’s learning.

These responses affirmed the importance of building positive teacher-student

relationships in VIPKid. All participants agreed on the importance of positive relationships and

their impact on teaching and learning. However, VIPKid is a distinctive context in which

teachers face both challenges and benefits to working to establish positive relationships with

their students.

Barriers

As an educational experience for children which incorporates English as a Foreign

Language instruction in a live, online context, there can be several barriers that hinder teachers

and students from forming positive relationships in this setting. The participants were given a list

of common barriers and asked to choose all that apply. This list included: not enough time in

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

22

class, lack of recurring classes with the same student, unfamiliarity with students’ lives, language

barrier, and cultural barrier (see Table 1). There was also space for teachers to choose to write

their own ideas about what barriers exist.

Table 1

Barriers to Creating Positive Teacher-Student Relationships

Answer Choices

Percentage of

Responses

Number of

Responses

Not enough time in class

61.11%

22

Lack of consistent, recurring classes with the

same student

58.33%

21

Unfamiliarity with students’ lives

44.44%

16

Language barrier

41.67%

15

Cultural barrier

36.11%

13

Barriers of time. Of the choices given, 22 respondents (61.11%) from this study found

that the biggest barrier to building positive relationships with their students was that they did not

have enough time in class. Each class is 25-minutes long and this constraint on time can be a

barrier in some cases. For example, some students complete the lesson objectives and activities

quickly and accurately which leaves time at the end of class to converse, play games, or talk with

students about their interests. Other students need the entire 25-minutes to complete the

objectives or review difficult content. While the primary goal is English language instruction,

many teachers feel that time to connect with their students aids the goal of instruction.

If teachers do not have time to begin building positive relationships in a single class, then

the benefit of recurring classes would be helpful. The second most popular choice among these

barriers was the lack of consistent, recurring classes with the same student. After choosing this

barrier as the only one from the list, one respondent wrote, “all you need is time to build a

relationship” (Participant 26). At VIPKid, parents of the students book classes with whichever

teacher they choose. Students are not assigned to specific teachers nor are they required to take

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

23

all classes with the same teacher. Parents may choose, however, to book the same teacher for

their child or they may choose to book classes with several different teachers. Some parents may

want to book the same teacher again, but find it too difficult to get a class because popular

teacher’s schedules fill too quickly. Others may want their child to learn from a variety of

teachers with different personalities and teaching styles. As a result, some teachers may only

teach a child one time for one lesson. Whatever the reason, 21 participants (58.33%) felt that this

inconsistency is a barrier to building relationships with students.

It should be noted that since the survey for this study was conducted, VIPKid has

initiated priority booking for students who have had a class with a teacher and would like to

continue with that same teacher. The student can request to book another class and the teacher

can approve this request. The priority booking function seems to have cut down on the

frustration of inconsistent bookings with the same students. With the implementation of this

function, students and teachers have been given more control over the number of classes they

have with the same teacher. At the time of the survey, one participant spoke to the positive

impact of recurring classes, writing:

For my students who have been able to book me regularly, I find the influence of the

language and cultural barriers and class times had disappeared as their English has

improved. I now know a lot about their lives and enjoy continuing to grow each teacher-

student relationship (Participant 34).

Barriers of distance. VIPkid is a distance-learning program that connects teachers in

North America with students in China. This distance can create various barriers to building

relationships. One barrier related to distance learning was that 44.44% teachers surveyed felt

they were unfamiliar with their students’ lives which was a hindrance to their relationships. One

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

24

participant felt that online learning has an “impersonal nature” (Participant 11). Another stated

that “not being able to communicate directly with the family” (Participant 6) was an issue that

created a barrier to building relationships. Teachers are able to leave written feedback for parents

and parents are able to leave comments for teachers when they review classes; however, this is

the extent of communication.

Another barrier that comes with the nature of VIPKid classes through distance education

is the inability to “eliminate certain distractions” (Participant 11). Many students take their

classes in their homes and generally this goes well; however, being at home means there can be

the distractions of siblings, toys, or video games. Well-intentioned parents can cause interference

during class as well. One teacher shared that “parents taking over a class can be a barrier”

(Participant 18). Parents who want their children to do well in class may interrupt, speak over the

child, or give answers before the child has opportunity to respond. VIPKid also has a mobile app,

which allows students to take classes anywhere. VIPKid teachers have taught their students in

taxis, restaurants, or while on vacation. These distractions can be problematic and interfere with

learning.

Barriers of language and culture. Although linguistic and cultural barriers may seem

obvious choices when teaching English as a Foreign Language, these barriers were the lowest

percentages from this survey. Of the respondents, only 15 (41.67 %) chose language as a barrier

and 13 (36.11%) chose culture. One participant stated that “as a teacher, it is up to us to break the

cultural barrier” (Participant 23), explaining that teachers can use the cultural differences to help

strengthen relationships by allowing students to share their traditions and culture in class.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

25

Teacher Techniques and Actions

Despite the barriers present in building relationships with their students at VIPKid,

teachers utilize a variety of techniques and actions to connect with their students. In order to

better understand the techniques used to overcome barriers, teacher participants were given the

following choices and were asked to check all that apply (see Table 2): correctly pronounce,

remember, and often use the student’s name; humor, laughter, fun; engaging props and rewards;

discussion of student interests and personal life; connection with parents through feedback.

Table 2

Techniques Used to Build Positive Teacher-Student Relationships

Answer Choices

Percentage of

Responses

Number of

Responses

Discussion of student interests and personal life

97.22%

35

Humor, laughter, fun

97.22%

35

Correctly pronounce, remember, and often use

student’s name

91.67%

33

Engaging props and rewards

75.00%

27

Connection with parents through feedback

75.00%

27

For those unfamiliar with VIPKid, the following choices regarding names, props and

rewards, and parent feedback have been expounded upon in order to offer a better understanding

of how these might help teachers overcome barriers in building relationships.

Names. Teachers agreed that remembering a student’s name was important. Many

students choose an English name for class, but some keep their Chinese names. It can be difficult

for someone who does not speak Chinese to read and pronounce names correctly, but it is one

way to connect with the students. Just as with any other relationship, remembering and calling

someone by their name shows care.

Props and Rewards. At VIPKid, teachers are encouraged to use props and rewards to

engage students. Props are anything that can enhance the lesson or better explain the vocabulary

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

26

and objectives. For example, when teaching letters and sounds, a teacher may use alphabet

flashcards. Rewards for the students can be stickers, games, or songs. Some teachers simply use

high-fives to rewards students while others have intricate games they play throughout class.

VIPKid has a built-in star reward system in which students can earn a total of 5 virtual stars per

class. Although all teachers use them in class, some teachers did not feel that props and rewards

were necessary or useful in building relationships with students. One teacher noted that “props

don’t have anything to do with building relationships, especially as most teachers reduce the use

of props with older students” (Participant 26).

Feedback. Teachers are required to leave feedback for parents after every class. This

feedback generally consists of notes about the student performance or suggestions for further

practice. Some teachers utilize this feedback in order to better understand student interests.

Teachers will leave questions for parents in the feedback and parents will then respond when

they leave a review for the class.

Teachers were also given the opportunity to share their own ideas and efforts in

overcoming barriers. Many teachers communicated similar themes when describing how they

overcome barriers to build relationships with students such as creating a safe and welcoming

environment, offering encouragement and support, or incorporating humor and laughter into

their lessons.

Safe and welcoming environment. Some teachers emphasized the importance of

creating a welcoming and safe learning environment for each student. In order to help guarantee

that students are safe in class, all VIPKid teachers must pass background checks. There are also

VIPKid employees who monitor classes and assist both students and teachers should any issues

arise during class. While VIPKid has these official safety measures in place, teachers were

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

27

referring to a different type of safety when they referenced safe environments. For example, one

teacher wrote that “students need to feel valued” and know that “the classroom is a safe space to

learn and grow” (Participant 22). Many teachers noted the act of simply smiling and having a

positive attitude can help create a more welcoming and inviting learning environment. Another

teacher commented that “the most important thing a VIPkid teacher can do to build positive

relationships with students is to smile” (Participant 17), explaining that a smile can communicate

that the teacher is supportive. Some felt that having high enthusiasm and energy during the

lesson could facilitate a positive learning environment despite barriers that may exist.

Encouragement and support. Many teachers wrote about the importance of offering

encouragement and support while teaching. Again, teachers emphasized smiling as one way to

show encouragement and support. Others wrote of patience, gentle correction, and an

encouraging attitude. Even if the child makes mistakes, teachers must try to “support their every

attempt” (Participant 31) at language learning. Praise and positive reinforcement also help to

encourage and support a student’s learning efforts. One teacher wrote about her efforts of

encouragement and support by stating, “I try to be empathetic and be their champion”

(Participant 32).

Another way in which teachers seek to support their students is by seeking to learn about

their students’ lives and interests. Some teachers connect with students simply by asking how

their day was and how they are feeling. Many teachers mentioned showing care and concern is a

key aspect to building relationships. One teacher stated that “showing genuine interest in the

student is key” (Participant 29). Others may bond by introducing their pets and discovering their

students are animal-lovers as well. Teachers may ask about favorite toys, foods, or sports to

establish a connection. One teacher (Participant 21) suggested that learning about student interest

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

28

can not only help teachers and students build relationships, but can also be used to enhance

learning by relating material to those student interests. For example, a student could practice

naming the colors on his favorite toy or using adjectives to describe that toy.

Humor and laughter. While encouraging smiles can help teachers overcome barriers,

humor and laughter can also facilitate positive relationship-building. VIPKid teachers work

exclusively with children under the age of 12. This younger student base allows teachers to use

silliness as a means of connection. Funny faces, comical voices, or exciting games may help

teachers connect with students on a different level. Several teachers mentioned bonding with

students by engaging them with humor and fun. Research shows that when humor is used

appropriately in the classroom, it can influence teacher-student relationships in a positive way

(Van Praag, Stevens, & Van Houtte, 2017).

Results and Benefits

Several teachers described the perceived results or benefits of forming positive

relationships with their students. When surveyed about the areas that are enhanced by positive

teacher-student relationships, the majority of teachers chose student motivation, student attitude,

student self-esteem, student language acquisition ability, teacher attitude, teacher motivation, and

Table 3

Areas Enhanced by Positive Teacher-Student Relationships

Answer Choices

Percentage of Responses

Number of Responses

Student Language Acquisition

Ability

100.00%

36

Student Attitude

97.22%

35

Teacher Attitude

97.22%

35

Student Motivation

97.22%

35

Teacher Motivation

94.44%

34

Student Self-esteem

91.67%

33

Teacher Energy

88.89%

32

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

29

teacher energy (see Table 3). Along with these given choices, teachers also explained other

benefits they believe result from positive relationships with their students.

Comfort and trust. Many VIPKid teachers believe that establishing positive

relationships with students can “lead to a more comfortable learning environment for both

students and teachers” (Participant 1). Many thought that making a student feel comfortable

could increase student learning and language output. As students begin to produce more

language in a comfortable environment, this can lead to building trust. Students who trust their

teachers are more willing to produce language. Teachers suggested that when students have

developed trust, they are willing to make more effort, work harder, and learn faster in the

classroom.

Confidence and security. Students who have high levels of comfort and trust in the

classroom are more likely to feel safe and develop confidence. One teacher (Participant 24)

shared that as a result of a positive relationship, the student felt “safe and confident when

learning” in the VIPKid classroom. Others wrote that building confidence is an important way

for teachers to facilitate the language acquisition process in their students.

Risk-taking and mistake-making. When students feel safe and confident, they are more

prepared to take risks and make mistakes in the language-learning process. Teachers placed high

value on the willingness of their students to take risks in their language efforts because it was

seen as a means to better language learning. Several teachers mentioned how students learn

directly from making mistakes. One teacher told the story of how a student pretended to teach

her stuffed animal English by correcting the toy’s mistakes which were similar to mistakes the

student had made in previous classes. The student learned from her own mistakes and practiced

teaching the correct forms to her toy in class.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

30

Trained or Untrained

The minimum educational requirements for VIPKid teachers is a bachelor’s degree in any

area. The company looks for teachers who have education experience with children and in

TESOL, but there are no formal requirements in either of these areas. Out of the 36 participants

in this survey, exactly half had some form of TESOL training and the other half did not. Training

ranged from ESL classroom experience or internships to online certificates to graduate degrees.

Despite the even sampling and variety of training, I could not find any indication that level of

training significantly informed views on building positive relationships with students. All

teachers agreed on the importance and influence of positive teacher-student relationships and,

while there were different perspectives on technique, emphasis, or experiences, these variations

did not seem dependent upon training. As Nel Noddings (2012) wrote, “Every human life starts

in relation, and it is through relations that a human individual emerges.” (p.771). All of the

teacher participants understood the importance of positive relationships with their students and

tried to achieve these relationships not because it is exclusively important in the field of TESOL,

but because it is ubiquitously significant to humankind.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

31

Chapter V: Implications of the Study

Despite different opinions, experiences, and training, all the teachers surveyed for this

study agreed that positive relationships with their students were extremely important and that

these relationships have benefits to both the teacher and student. There are certain barriers that

exist to forming these relationships, but VIPKid teachers work hard to overcome them and

connect with their students in meaningful and positive ways. As a result of this study, there are

some implications for both teachers working with VIPKid, and the staff at the main office of

VIPKid.

Overcoming barriers. One of the biggest barriers that teachers felt hindered them from

building positive relationships with students was that of time. Whether it was not enough time in

class or not enough recurring classes with the same student, teachers felt that more time with

students would better facilitate building relationships. Since the survey was conducted, VIPKid

has made efforts in allowing students and teachers to keep consistent classes by allowing the

priority booking feature which was discussed earlier in this paper. This function has the potential

to help teachers overcome the lack of consistent classes with the same student which many felt

was a barrier.

Barriers that come with distance education were also mentioned. Because teachers do not

have direct lines of communication with the parents, many have joined the Chinese social media

platform WeChat. VIPKid does not officially support or encourage this connection as they

cannot be held responsible for misconduct on behalf of the parents or teachers involved.

However, in light of this disconnection with parents being seen as a barrier, VIPKid should

consider a better method for teachers and parents to communicate. It could be as simple as

parents filling out a questionnaire about the students’ interests, goals, and learning styles. This

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

32

simple form of communication would give a basis on which teachers could begin building

relationships even within the confine of a short, 25-minute class period.

Although language and culture is a potential barrier in any English as a Foreign Language

(EFL) context, VIPKid already does an excellent job offering linguistic and cultural educational

opportunities for their teachers. Through the use of videos and articles provided by VIPKid,

teachers have been given opportunities to learn about the language, history, and culture of China.

As some teachers mentioned in this study, teachers can take advantage of the culture and

language difference by giving the students opportunities to share. The student can become the

teacher and share their expertise on Chinese language and culture during class as time and

lessons allow.

Applying techniques. The overarching theme presented by teachers for actively pursuing

positive relationships with students was care for the student. Teachers showed care in a variety of

ways such as creating a welcoming and safe class environment, offering encouragement and

support to the student, and using humor and laughter during class.

Some teachers employed simple techniques such as remembering and using the students

name and lots of smiles. These techniques are easy to apply, but can have a great impact on

making a student feel welcome and cared for. Teachers also used props and rewards with

students, although some did not feel this had any bearing on relationships.

Seeking to learn more about the students’ interests and lives was a technique that many

teachers felt was profitable for building relationships. Some teachers utilized feedback to ask the

parents to share the students’ favorite things. Knowing students’ interests helped teachers to have

a foundation to begin relationships, but it was also applied in the classroom to help better engage

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

33

students in learning during the lessons. VIPKid could be more proactive in helping teachers

obtain this knowledge by encouraging parents to share.

Working toward results. The data collected for this study was based solely on teacher

perception and experience. It is significant that 100% of teachers surveyed thought that their

students’ language acquisition ability was enhanced by having positive relationships with

teachers. In fact, most teachers agreed that positive relationships with the students had a variety

of benefits for the teachers and students (see Table 3). Whether or not students agree with these

benefits is beyond the scope of this study, but because the teachers surveyed received benefit

from connecting with students, other teachers should be motivated to build these positive

relationships as well. Teachers bear the weight of this responsibility to build relationships with

their students. While the task can be daunting in this context, teachers can be encouraged to

practice communicating care in the classroom. Smiles, enthusiasm, and seeking to understand

student interests are simple ways to begin building positive relationships with students. It would

be helpful for VIPKid to continue to listen and partner with teachers in order to help them build

relationships with their students. Teachers should share their concerns and suggestions with the

company in order to improve teacher-student relationships in this context. Teachers can also

encourage one another by reminding each other of the importance of the relationships with

students and sharing ideas for communicating care.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

34

Chapter VI: Conclusion

Limitations of the Study

This study was conducted to better understand positive teacher-student relationships from

the perspectives of the teachers. All responses of this study were in writing from the teachers.

The researcher did not view the teachers applying any techniques during their classes and did not

observe the nature of any relationships with the students. No information was gathered from the

students for this study. Although teachers may feel their efforts toward building positive

relationships with their students are successful, there was no evidence collected in this study to

confirm those efforts were well-received by the students.

The teacher participants all work within the context of VIPKid. The results are

representative of teachers’ perspectives in this specific context. These results may be influenced

by company environment, policy, or training. In this context, all of the students are Chinese.

Therefore, the findings of this study reference building relationships with Chinese students.

Teachers who work in online EFL contexts with a different company or with students from

different countries may have varying perspectives on building relationships with students.

Future Recommendations for Study

In order to build on this study and corroborate the findings, it would be beneficial to

conduct a study on student perspectives about positive relationships with their teachers. VIPKid

teachers could better understand what practices actually make students feel supported,

encouraged, and valued by listening to the students’ voices. The students’ perspectives are just as

important as the teachers’ as both parties should feel that the relationship is a positive one. It may

also be beneficial to observe actual VIPKid classes in which students and teachers both feel a

positive relationship has been established. By observing the actions and responses of students, a

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

35

researcher could corroborate and add to teacher perspectives about how to build positive

relationships with students.

In order to explore contributing factors to perspectives in building relationships with

students in other online EFL contexts, studies conducted with teachers from a different company

would add to the body of research. It would also be gainful to study how teachers in similar

online EFL contexts build relationships with students from countries other than China. Future

studies could help determine if the perspectives of teachers on building positive teacher-student

relationships found in this study are confined to this specific context.

Personal Impact of the Study

As a student of TESOL and a VIPKid teacher, I was curious about the perspectives of

other teachers on building relationships with their students. I conducted this study for both

professional and personal benefit. I was encouraged to learn that teachers who participated, both

trained and untrained, unanimously agreed that positive relationships with their students are

important. These findings supported the abundance of research that shows that positive teacher-

student relationships do matter in education.

I was also able to grow in my own understanding of relationships with my students as

well as apply some of the techniques suggested by other teachers. It can be easy in this fast-

paced, distance-learning context to be focused on getting through the content of that 25-minute

class period and moving on to the next without being intentional to connect with the student.

This study was a wonderful reminder for me to find ways to intentionally communicate care for

each of my students in every class. I appreciated the simple advice, such as giving students lots

of encouraging smiles, that could be immediately applied in class. I have always enjoyed my

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

36

students, but this study was an encouragement to be purposeful in viewing my students as people

who should be valued and cared for and not simply taught and assessed.

Summary

In order to better understand the perceptions of VIPKid teachers about building positive

relationships with their students, I conducted a survey in which 36 teachers responded. Teachers

answered questions about their views on positive relationships, barriers to positive relationships,

and techniques for building positive relationships in the context of VIPKid. All teachers

surveyed understood the importance of positive teacher-student relationships. Teachers had

different opinions on which barriers exist to building those relationships and how to overcome

them. Teachers shared a variety of thoughts on engaging students in order to build relationships,

but most responses centered on communicating care for the student. For the last question on the

survey, I asked teachers to share what they felt was the most important thing a VIPKid teacher

could do in order to build positive relationships with their students. I have incorporated many of

those ideas throughout this report, but one response seemed to summarize consensus: “Show a

genuine interest in the students. Be caring, attentive, and thoughtful. Treating the students like

they are individuals and not just one of the many you have to teach that week makes all the

difference.” (Participant 35). Regardless of the potential barriers they may face, this advice can

surely help VIPKid teachers build positive relationships with their students.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

37

References

Basal, A. (2015). The implementation of a flipped classroom in foreign language teaching.

Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 16 (4), pp. 28-37. Retrieved from

http://www.eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=EJ1092800

Bernstein-Yamashiro, B. & Noam, G. (2013). Teacher-student relationships: A growing field of

study. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2013(137), pp. 15-26. doi:

10.1002/yd.20045

Bernstein-Yamashiro, B. & Noam, G. (2013). Learning together: Teaching, relationships, and

teachers’ work. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2013(137), pp. 45-56. doi:

10.1002/yd.20047

Bloomberg News (2017, August 23). China’s VIPKid is said to raise funds at $1.5 billion

valuation. Bloomberg Technology. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com

Bruster, B. (2015). On-line course development: Engaging and retaining students. SRATE

Journal, 24(2), pp. 1-7.

Center on Education Policy. (2016). Listen to us: Teacher views and voices. Retrieved from

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED568172

Conboye, J. (2018, January 28). Entrepreneurship: VIPKid founder Cindy Mi’s global online

classroom. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com

Creswell, J. (2015). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative

and qualitative research (5

th

ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Fallows, D. (2015, June 12). How ‘thank you’ sounds to Chinese ears. The Atlantic. Retrieved

from www.theatlantic.com

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

38

Hamre, B. & Pianta, R. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s

school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625-638. Retrieved

from https://eric.ed.gov/?q=EJ635749&id=EJ635749

Hughes, J. (2011). Longitudinal effects of teacher and student perceptions of teacher student-

student relationship qualities on academic adjustment. The Elementary School Journal,

112(1), 38-60. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.messiah.edu/10.1086/660686

Hughes, J. & Wu, J. (2012). Indirect effects of child reports of teacher-student relationship on

achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), pp. 350-365. Retrieved from

http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.messiah.edu/10.1037/a0026339

Jiménez, R. & Rose, B. (2010). Knowing how to know: Building meaningful relationships

through instruction that meets the needs of students learning English. Journal of Teacher

Education, 61(5), pp. 403-412. doi: 10.1177/00224871 10375805

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practices in second language acquisition. Retrieved from

http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_practice.pdf

Leibold, N. & Schwarz, L. (2015). The art of giving online feedback. The Journal of Effective

Teaching, 15(1), pp.34-46. Retrieved from

http://www.eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=EJ1060438

Lewis, A. (2001). The issue of perception: Some educational implications. Educare, 30(1+2), pp.

272-288. Retrieved from

http://www.andrewlewis.co.za/Lewis.Perception.Educare1_v30_n1_a15.pdf

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

39

Medina-López-Portillo, A. (2014). Preparing TESOL students for the ESOL classroom: A cross-

cultural project in intercultural communication. TESOL Journal, 5(2), pp. 330-352. doi:

10.1002/tesj.122

Noddings, N. (2005). Identifying and responding to the needs in education. Cambridge Journal

of Education, 35 (2), pp. 147-159. doi: 10.1080/03057640500146757

Noddings, N. (2012). The caring relation in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 38(6), pp.

771-781. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080.03054985.2012.745047

Ogilvie, G. & Fuller, D. (2016). Restorative justice pedagogy in the ESL classroom: Creating a

caring environment to support refugee students. TESL Canada Journal, 33(10), pp. 86-

96. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/1018806/tesl.v33i0.1246

Positive-Teacher Student Relationships. (2018). Survey on SurveyMonkey. Retrieved from

www.surveymonkey.com

Sánchez, C., González, B., & Martínez, C. (2013). The impact of teacher-student relationships on

EFL learning. HOW, A Columbian Journal for Teachers of English, 20, pp. 116-129.

Retrieved from

http://www.eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=EJ1128082

Stewart, M. (2016). Nurturing caring relationships through five simple rules. English Journal,

105(3), pp. 22-28. Retrieved from

http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/EJ/1053-

jan2016/EJ1053Nurturing.pdf

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

40

Strickland, M., Keat, J., & Marinak, B. (2010). Connecting worlds: Using photo narrations to

connect immigrant children, preschool teachers, and immigrant families. The School

Community Journal, 20(1), pp.81-102.

Teven, J. J. & McCroskey, J. C. (1997). The relationship of perceived teacher caring with student

learning and teacher evaluation. Communication Education, 46, 1–9. Retrieved from

https://eric.ed.gov/?q=EJ537309

Tomlinson, B. (2016). Interview with Brian Tomlinson on Humanising Education/Interviewer: V.

Nimehchisalem [transcript]. International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies, 4(2),

pp.101-106. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.4n.2p.101

Tracy, S. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis,

communicating impact. West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Van Pragg, L., Stevens, P., & Van Houtte, M. (2017). How humor makes or breaks student-

teacher relationships: A classroom ethnography in Belgium. Teaching and Teacher

Education, 66 (2017), pp. 393-401. Retrieved from

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.008

Wang, L. & Du, X. (2014). Chinese teachers’ professional identity and beliefs about the teacher-

student relationships in an intercultural context. Frontiers of Education in China, 9(3),

pp. 429-455. doi: 10.3868/s110-003-014-0033-x

Yunus, M.M., Osman, W., & Ishak, N. M. (2011). Teacher-student relationship factor affecting

motivation and academic achievement in ESL classroom. Procedia Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 15, 2637-2641.

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

42

Appendix A

Positive Teacher-Student Relationships Survey

1. How long have you been teaching with VIPKID?

a. 6-12 months (2

nd

contract)

b. 12-18 months (3

rd

contract)

c. 18-24 months (4

th

contract)

d. More than 2 years (5

th

+ contract)

2. Are you trained or certified in TESOL? Is so, please list training or certification.

3. Do you feel that positive relationships with students are important? Why or why not?

4. Do you believe that positive teacher-student relationships enhance your teaching and the

students’ learning in this context? Why or why not?

5. Have you seen a student improve or perform better after a positive connection was made

with you, the teacher? Please share your story.

6. In your experience, positive teacher-student relationships can improve (check all that

apply):

a. Student motivation

b. Student attitude

c. Student self-esteem

d. Student language acquisition ability

e. Teacher attitude

f. Teacher motivation

g. Teacher energy

h. Other

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

43

7. What techniques or methods do you use to build positive relationships with your

students? Mark all that apply.

a. Correctly pronounce, remember, and often use the student’s name

b. Humor, laughter, fun

c. Engaging props and rewards

d. Disucussion of student interests and personal life

e. Connection with parents through feedback

8. What barriers to creating positive relationships with students exist in this online context?

Mark all that apply.

a. Language barrier

b. Cultural barrier

c. Not enough time in class

d. Unfamiliarity with students’ lives

e. Lack of consistent, recurring classes with the same student

f. Other

9. What efforts have you made to overcome barriers in order to connect with students?

Please share your experience.

10. What do you feel is the most important thing a VIPKID teacher can do to build positive

relationships with students?

Survey Monkey Link: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/YZ2HRDN

EXPLORATION OF POSITIVE TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

44

Appendix B

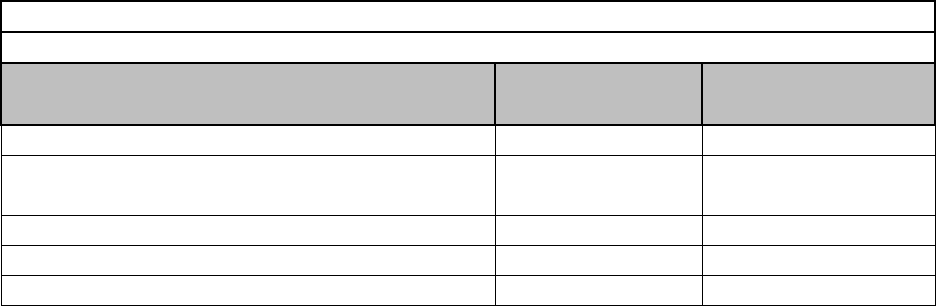

Picture 1:Following an assessment, a regular student shared a video of himself playing the piano. You can see my shock as I

watched him skillfully play Für Elise. I had no idea he played piano until his until this moment.

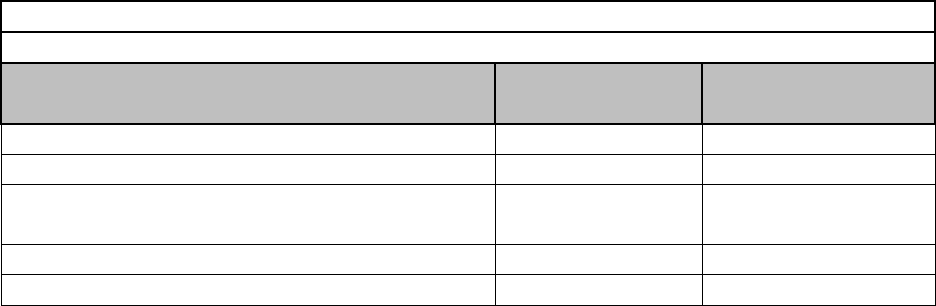

Picture 2: A student shared her favorite book in English which happened to be one of my favorites as well.