Chapter 2:

Principles for

Assessing Medicaid

Nursing Facility

Payment Policies

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

28

March 2023

Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing

Facility Payment Policies

Recommendations

2.1 To improve transparency of Medicaid spending, the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services should direct the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to collect and report the

following data in a standard format that enables analysis:

•

facility-level data on all types of Medicaid payments to nursing facilities, including resident

contributions to their cost of care;

•

data on the sources of non-federal share of spending necessary to determine net Medicaid

payment at the facility level; and

•

comprehensive data on nursing facility nances and ownership necessary to compare Medicaid

payments to the costs of care for Medicaid-covered residents and to examine the eects of real

estate ownership models and related-party transactions.

2.2 To help inform assessments of whether Medicaid nursing facility payments are consistent with

statutory goals of eciency, economy, quality, and access, the Secretary of the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services should direct the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to

update the requirement that states conduct regular analyses of all Medicaid payments relative to the

costs of care for Medicaid-covered nursing facility residents. This analysis should also include an

assessment of how payments relate to quality outcomes and health disparities. CMS should provide

analytic support and technical assistance to help states complete these analyses, including guidance

on how states can accurately identify the costs of ecient and economically operated facilities with

adequate sta to meet residents’ care needs. States and CMS should make facility-level ndings

publicly available in a format that enables analysis.

Key Points

•

Medicaid is the largest payer for nursing facility care and has an important role to play in reducing

health disparities that have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

•

Medicaid payment rates and methods vary widely by state, and there are limited data available about

how rates compare to costs and how Medicaid payment policies aect quality outcomes.

•

Most Medicaid-covered nursing facility residents are dually eligible for Medicare, but payment

incentives for Medicare and Medicaid are not well aligned.

•

To advance Medicaid statutory goals of eciency, economy, quality, and access, states should do the

following:

– ensure that nursing facility payment rates are sucient to cover the costs of ecient and

economically operated facilities;

– design payment methods to incentivize better quality outcomes and reduce health disparities; and,

– aim to get the maximum value for the amount that they are spending.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

29

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

CHAPTER 2: Principles

for Assessing Medicaid

Nursing Facility

Payment Policies

Medicaid is the largest payer for nursing facility care

and has an important role to play in improving the

care that nursing facility residents receive. However,

facilities that serve a high share of Medicaid-covered

residents have long had worse quality outcomes on

average than other facilities. The COVID-19 pandemic

has exposed and exacerbated many of these

disparities. In response, policymakers are considering

a variety of reforms to how they regulate and pay for

nursing facility care.

The Commission has identied several principles

for states to consider when setting Medicaid nursing

facility payment rates and payment methods. These

principles are intended to advance the statutory goals

of Medicaid payment policy: economy, eciency,

quality, and access (§1902(a)(30)(A) of the Social

Security Act (the Act)).

First, in the Commission’s view, Medicaid payments

should be sucient to cover the costs of ecient

and economically operated nursing facilities. When

assessing payment adequacy, states should consider

all types of Medicaid payments that providers receive

and review reported costs carefully. For example,

states should consider the costs of stang facilities at

appropriate levels to meet residents’ care needs and

the potential for transactions with related parties in the

same nursing facility chain to inate costs reported on

state cost reports.

Second, states should design nursing facility payment

methods to incentivize better quality outcomes and

reductions in health disparities. Although many of

the factors that aect quality care are outside of

Medicaid’s authority, the persistent disparities between

Medicaid-covered residents and those covered by

other payers are an issue that Medicaid payment

policy can help address. Doing so would also help

reduce racial and ethnic disparities.

Finally, nursing facility payment policies should be

evaluated based on whether they are ecient—that

is, whether states are getting the maximum value for

the amount they are spending. Comparing payment

rates and quality outcomes across states can help

identify potential opportunities to improve eciency,

particularly in states with relatively high payment rates

and poor outcomes. In addition, policymakers should

continue to explore opportunities to improve eciency

across payers by better aligning payment incentives

for patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

More detailed state-level analyses are needed to

identify the best approaches for each state, which

would require increased state capacity to examine

these issues.

The Commission recommends that the Secretary of

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

(HHS) direct the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) to take the following actions to

improve the availability of data to assess whether state

payment policies are consistent with these principles:

•

To improve transparency of Medicaid spending,

the Secretary of HHS should direct CMS to

collect and report the following data in a standard

format that enables analysis:

– facility-level data on all types of Medicaid

payments to nursing facilities, including

resident contributions to their cost of care;

– data on the sources of non-federal share

of spending necessary to determine net

Medicaid payment at the facility level; and

– comprehensive data on nursing facility

nances and ownership necessary to

compare Medicaid payments to the costs of

care for Medicaid-covered residents and to

examine the eects of real estate ownership

models and related-party transactions.

•

To help inform assessments of whether Medicaid

nursing facility payments are consistent with

statutory goals of eciency, economy, quality, and

access, the Secretary of HHS should direct CMS

to update the requirement that states conduct

regular analyses of all Medicaid payments

relative to the costs of care for Medicaid-covered

nursing facility residents. This analysis should

also include an assessment of how payments

relate to quality outcomes and health disparities.

CMS should provide analytic support and

technical assistance to help states complete

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

30

March 2023

these analyses, including guidance on how states

can accurately identify the costs of ecient and

economically operated facilities with adequate

sta to meet residents’ care needs. States and

CMS should make facility-level ndings publicly

available in a format that enables analysis.

The Commission reviewed data on Medicaid payment

methods, payment amounts, and quality outcomes

to better understand the factors that aect the

development of nursing facility payment policies and

whether they are achieving their intended goals. This

chapter summarizes the Commission’s analyses, which

informed the development of the Commission’s payment

principles and recommendations. The chapter begins

with background information on nursing facility industry

trends and Medicaid’s role relative to other payers. Then

it discusses current Medicaid payment policies, how they

can be used to improve quality, and how they align with

other payers. The chapter concludes by discussing the

payment principles, recommendations, and supporting

rationale in more detail.

As more information on Medicaid nursing facility

payments becomes available, the Commission

will continue to monitor state payment policies. In

particular, the Commission will closely follow how any

future changes in federal regulatory requirements (e.g.,

minimum stang standards) aect states, providers,

and beneciaries.

Background

Nursing facilities are institutions certied by a state

to oer 24-hour medical and skilled nursing care,

rehabilitation, or health-related services to individuals

who do not require hospital care.

1

Medicaid is the

primary payer for most nursing facility residents, but

it generally pays less than other payers. The nursing

facility industry faces a number of challenges, which

are generally worse for facilities that serve a high

share of Medicaid-covered residents and have been

exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Role of nursing facilities in the

continuum of care

Nursing facilities provide both short-term care for

patients recovering from a hospital stay and long-

term care for residents who need ongoing assistance

with activities of daily living. Of the approximately 1.1

million patients and residents receiving care in nursing

facilities on September 30, 2019, about half had short

stays of less than 100 days, and half had long stays of

more than 100 days (Abt Associates 2020).

2

The short-term care that nursing facilities provide

(referred to as “skilled nursing facility (SNF) services”)

is part of the continuum of post-acute care after a

hospital stay. Nursing facilities generally provide more

intensive care than home health providers and less

intensive care than rehabilitation or long-term care

hospitals. In 2019, nursing facilities accounted for

about half of all Medicare hospital discharges to post-

acute care providers (MedPAC 2022a).

The long-term care that nursing facilities provide is

also part of the continuum of long-term services and

supports (LTSS). Nursing facility services remain an

important site of care for beneciaries who are not able

to receive care in the community. In scal year 2019,

nursing facility services accounted for about 80 percent

of Medicaid spending on institutional LTSS, 33 percent

of total Medicaid LTSS expenditures, and 11 percent of

total Medicaid spending (Murray et al. 2021).

3

Medicaid coverage of nursing

facility care

In 2019, Medicaid was the primary payer for 59

percent of nursing facility residents (Figure 2-1). Most

Medicaid-covered nursing facility residents had long

stays, but about one-quarter of Medicaid-covered

residents had short stays of less than 100 days.

Medicare is the largest payer of short-stay nursing

facility residents. About 19 percent of nursing facility

residents were not covered by either Medicare or

Medicaid. Long-stay residents not covered by Medicare

or Medicaid likely paid for their care out of pocket

because private insurance coverage for long-term care

is rare.

4

About 90 percent of Medicaid-covered nursing facility

residents are older than age 65 (Abt Associates 2020).

Non-elderly Medicaid beneciaries with a need for

institutional LTSS are often served in other settings,

such as intermediate care facilities for individuals with

intellectual or developmental disabilities, which are

outside the scope of this chapter (ASPE 2013).

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

31

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

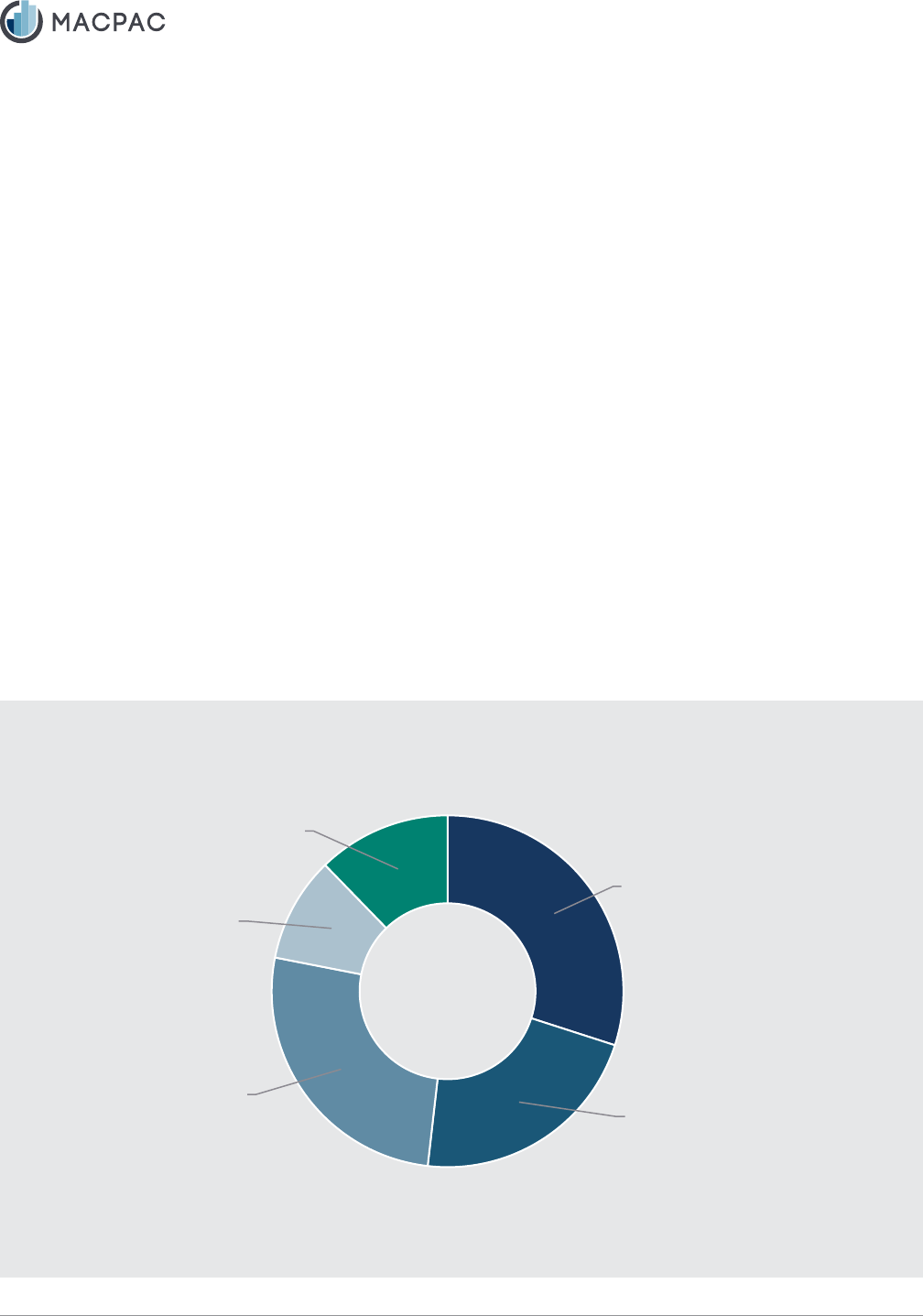

FIGURE 2-1. Characteristics of Nursing Facility Patients and Residents by Primary Payer and Length of

Stay, 2019

Medicare,

short stay,

22%

Other, short stay,

11%

Other, long stay, 8%

Medicaid,

short stay,

27%

Medicaid,

long stay,

73%

Medicaid, 59%

Notes: Short-stay patients are dened as individuals residing in the facility for less than 100 days. Long-stay

residents are dened as residing for more than 100 days. Analysis is based on nursing facility residents who were

active on September 30, 2019. Length of stay is based on the number of days between the entry date and the target

date of the latest Minimum Data Set assessment used in the analysis, not the discharge date of the stay.

Source: Abt Associates 2020.

Medicaid eligibility requirements. To qualify for

Medicaid coverage, nursing facility residents must

have low income and assets. Many Medicaid-

covered nursing facility residents are eligible through

mandatory eligibility pathways that are tied to the

receipt of supplemental security income (SSI), which

in 2022 had an income limit of $841 a month and an

asset limit of $2,000 for individuals. As of 2018, 42

states also provided Medicaid coverage to nursing

facility residents with incomes up to 300 percent of

the SSI limit (an option referred to as the “special

income rule”), 25 states used the medically needy

option to allow higher-income individuals to qualify

for Medicaid coverage by subtracting the amount that

they paid for their care from their income (a process

referred to as “spenddown”), and 21 states provided

coverage to seniors and persons with disabilities up

to 100 percent of the federal poverty level regardless

of whether they had a nursing facility level of care

(referred to as the “poverty-level pathway”) (Musumeci

et al. 2019).

5

According to an analysis by the HHS

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation using

2006–2007 data, 22 percent of Medicaid-covered

nursing facility residents qualied through SSI-related

pathways, 50 percent qualied through the special

income rule, 21 percent qualied through a medically

needy pathway, and about 7 percent qualied through

the poverty-level pathway (ASPE 2013).

Because the out-of-pocket costs for nursing facility

care are substantial and few individuals have private

long-term care insurance, many private-pay nursing

facility residents with long stays eventually become

eligible for Medicaid after spending most of their

income and assets toward the cost of their care.

6

In

2001, more than half of Medicaid-covered nursing

facility residents began their Medicaid coverage

after residing in the nursing facility, and 21 percent

of Medicaid-covered residents began coverage

after residing in the facility for more than six months

(Wenzlow et al. 2008).

Post-eligibility treatment of income. Unlike many

other Medicaid beneciaries who have little or no cost-

sharing obligations, recipients of LTSS are required

to contribute most of their income toward the cost of

their care through a process known as “post-eligibility

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

32

March 2023

treatment of income.” The amount of income that a

beneciary can retain is set by the state’s personal

needs allowance and other exceptions.

7

In 2018, the

median state personal needs allowance for institutional

care was $50 per month, meaning that in most

states, all but a small amount of a Medicaid-covered

resident’s income went toward the cost of their care

(Musumeci et al. 2019).

Residents’ contributions to the cost of their care reduce

the amount of state and federal Medicaid payments

that a facility receives. In 2019, these contributions

accounted for about 10 percent of Medicaid payments

to nursing facilities (MACPAC 2023a).

Patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

The vast majority (84 percent) of Medicaid-covered

nursing facility residents are dually eligible for

Medicare and Medicaid (Abt Associates 2020). For

these beneciaries, Medicare pays for SNF care

during the initial portion of their stay, and Medicaid

pays for subsequent days of care. Medicare Part

B also continues to cover physician and therapy

services for long-stay nursing facility residents after

the Medicare Part A SNF benet is exhausted.

State Medicaid programs have the option to pay for

Medicare cost sharing during the initial portion of the

stay, but most do not, which results in lower payments

to the facility (MACPAC 2013).

Medicaid payments compared with

other payers

According to the National Health Expenditure

Accounts, Medicaid accounted for 30 percent of total

revenue for all nursing facilities, including those that

were part of continuing care retirement communities,

in 2019 (Figure 2-2). Although Medicaid is the largest

payer for nursing facility services, Medicaid payments

as a share of total revenue are much lower than

the share of nursing facility residents covered by

Medicaid (59 percent) (Abt Associates 2020). Medicaid

payments are generally lower than other payers

because of dierences in the services that Medicaid

covers and because Medicare typically pays facilities

much more than the costs of care for Medicare-

covered patients.

FIGURE 2-2. Sources of Revenue for Nursing Facilities and Continuing Care Retirement Communities,

2019

Medicaid, 30%

Medicare, 22%

Private health

insurance, 10%

Other third-party

payers, 12%

Out-of-pocket

spending, 26%

Note: Analysis includes all certied nursing facilities, including those part of continuing care retirement communities.

Source: OACT 2022.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

33

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

Dierences in resident acuity and covered services.

Medicaid payment rates are not comparable to those

in Medicare because of dierences in resident acuity

and the services that Medicaid covers. First, long-stay

residents, who are predominately covered by Medicaid,

generally have less intensive nursing and therapy care

needs than short-stay patients covered by Medicare,

so the costs of their care are lower (MACPAC 2023a,

Abt Associates 2020). Second, for patients dually

eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, Medicare Part

B continues to pay for some physician and therapy

services for long-stay residents, and so these services

are not included in the Medicaid rate. Third, because

of Medicaid spenddown and post-eligibility treatment of

income rules, many Medicaid-covered residents pay for

a substantial portion of their care out of pocket, which

reduces the amount that Medicaid pays the facility.

Medicare payment rates often exceed facility

costs. According to the Medicare Payment Advisory

Commission (MedPAC), Medicare has long paid SNF

payments much more than their costs of care for

Medicare-covered patients. For example, freestanding

nursing facilities reported a 20 percent aggregate

Medicare prot margin in scal year 2019, compared

with an aggregate non-Medicare margin of -2 percent

(MedPAC 2021). Although some stakeholders contend

that high Medicare payment rates are justied because

they can oset low Medicaid payment rates, MedPAC

has long argued that this policy is inecient, since

the policy benets facilities that serve more Medicare-

covered residents instead of facilities that serve a

high share of Medicaid-covered residents (MedPAC

2022b). In addition, because Medicare payment rates

are set nationally, they do not account for dierences

in Medicaid payment rates across states. As discussed

in the following sections, state payment rates vary

widely, and in some states, facilities report positive

Medicaid margins.

Industry trends

In 2019, there were 15,462 certied nursing facilities

nationwide. Most nursing facilities (93 percent) are

certied by both Medicare and Medicaid, and most of

these facilities (97 percent) are freestanding, meaning

that they are not based within a hospital. Roughly

9 percent of facilities are part of a continuing care

retirement community, which includes assisted living

options in addition to certied nursing facility beds (Abt

Associates 2022).

Ownership. In 2022, most nursing facilities (72 percent)

were for prot, and about two-thirds of facilities (66

percent) were also part of a larger chain.

8

Nursing

facility chains vary widely in size: in 2022, about 15

percent of nursing facilities were part of chains with

10 facilities or fewer, and about 11 percent of nursing

facilities were part of chains with more than 100 facilities

(ASPE 2022a).

Between 2016 and 2021, a total of 3,254 nursing

facilities were sold, and the pace of transactions has

generally increased since 2016 (ASPE 2022b). About

one-third of these transactions involved multiple owners

(ASPE 2022b). For example, multiple related parties

can own a nursing facility when a private equity rm

purchases a nursing facility, sells the real estate to

another entity, and then leases the building to a third

entity that manages the care provided.

Declining occupancy rates. Even before the

COVID-19 pandemic, nursing facility occupancy rates

were declining, which creates nancial challenges for

facilities that must continue to pay xed overhead and

capital costs with declining revenue. Between 2010 and

2019, occupancy rates declined from 88 to 85 percent,

in part because of eorts to shift care to home- and

community-based services, and since the start of the

COVID-19 pandemic, occupancy rates have declined

even further (MedPAC 2022b). In January 2021, median

occupancy rates reached a low of 69 percent, and by

November 2022, median occupancy rates were 78

percent (CLA 2023).

Nursing facility closures. Between 2015 and 2019,

more than 500 nursing facilities closed (Flinn 2020).

Although some closures are expected as care shifts

from nursing facilities to other settings, closures can be

particularly problematic in rural areas where residents

may not have access to other facilities nearby where

their loved ones can easily visit. In 2018, 7.7 percent

of U.S. counties had no nursing facility, an increase

of 44 counties since 2008; these closures were more

common in facilities that served a higher share of

Medicaid-covered residents (Sharma et al. 2021).

New care models. Despite the challenges that

the nursing facility industry faces, some providers

are testing new models of care that reect resident

preferences for less institutional, more homelike

settings. One example is the Green House initiative

launched in 2003 with funding from the Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation. In contrast to the average

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

34

March 2023

nursing facility, which has about 100 beds with many

shared rooms, facilities participating in the Green

House initiative have about 10 to 12 beds and single-

occupancy rooms. The model has shown promising

quality outcomes, but these facilities represent less

than 2 percent of nursing facilities and serve less than 1

percent of all nursing facility residents. Moreover, these

facilities report that it has been challenging to expand

access to more Medicaid-covered nursing facility

residents because of Medicaid payment rates and state

limitations on Medicaid covering private rooms if they

are not medically necessary (Waters 2021).

Facilities that serve a high share of

Medicaid-covered residents

The payer mix of Medicaid, Medicare, and private-

pay residents varies widely and is associated with a

number of facility characteristics (Table 2-1). Although

some of these dierences may reect facility decisions

on whether to accept more short-stay patients versus

long-stay residents, they also reect facility decisions

about whether to accept Medicaid-covered residents.

Federal law prohibits facilities from discharging a

resident once they become Medicaid eligible, but

in many states, facilities can choose to not admit

residents who are likely to become Medicaid eligible.

9

As a result, there is evidence that Medicaid-covered

residents may have more diculty accessing high-

quality facilities (Sharma et al. 2020).

Quality ratings. On average, facilities that serve a

high share of Medicaid-covered residents have lower

quality ratings than other facilities on all of the domains

measured by the Medicare.gov Care Compare ve-

star rating system (Box 2-1). However, there is wide

variation in the quality of care provided to Medicaid-

covered residents, and in 2019, 12 percent of facilities

that served the highest quartile of Medicaid-covered

residents had ve-star ratings overall (the highest

on Care Compare) compared with 21 percent of all

facilities in our analysis.

TABLE 2-1. Facility Characteristics by Payer Mix, 2019

Characteristics All facilities

Share of residents whose primary support was Medicaid

Lowest

quartile

(< 48%)

Second

quartile

(48–61%)

Third

quartile

(61–71%)

Highest

quartile

(> 71%)

Average Medicare.gov Care Compare ve-star quality ratings

Overall rating 3.1 3.7 3.1 2.8 2.7

Inspection component 2.7 3.2 2.8 2.6 2.4

Stang component 2.9 3.4 2.9 2.7 2.6

Quality measure component 3.6 3.9 3.6 3.5 3.4

Race and ethnicity of nursing facility residents

White, non-Hispanic 77% 86% 81% 74% 65%

Black, non-Hispanic 13 7 10 15 21

Hispanic 5 3 4 6 7

Other 5 5 5 6 6

Ownership

Private, for prot 74% 56% 73% 82% 84%

Private, non-prot 21 38 22 13 11

Public 5 6 5 5 5

Note: Analysis excludes hospital-based nursing facilities and those that are not dually certied by Medicaid and Medicare.

Sources: MACPAC, 2022, analysis of Medicare.gov Care Compare, Medicare cost reports, and the Minimum Data Set.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

35

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

Racial and ethnic disparities. Facilities serving

a high share of Medicaid-covered residents also

serve more racial and ethnic minorities, so poor

quality ratings in these facilities contribute to health

disparities. In general, Black Medicaid beneciaries

are more likely than white Medicaid beneciaries

to receive care in nursing facilities, and when they

do, they are less likely to be admitted to high-quality

facilities (Zuckerman et al. 2018). The racial and ethnic

disparities in nursing facility care are long standing

and have persisted even as other health care settings,

such as hospitals, have been desegregated (Nolen et

al. 2020).

Facility ownership. For-prot facilities are more likely

to serve a high share of Medicaid patients than non-

prot facilities. For-prot facilities generally have lower

stang levels than other facilities and have lower

average quality ratings than other types of facilities

(Paul et al. 2016). As a result, some of the dierences

in quality by payer mix that we observe may be a

result of dierences in facility ownership. Recent

research has highlighted additional quality challenges

in for-prot facilities owned by private equity investors,

but we do not have data to distinguish these facilities

from other for-prot facilities (Braun et al. 2021, Gupta

et al. 2021).

BOX 2-1. Medicare.gov Care Compare Five-Star Ratings for Nursing

Facilities

Since 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has been reporting ve-star quality

ratings for nursing facilities on its Medicare.gov Care Compare website. The composite ve-star rating is

based on three components that have continued to be rened over time:

•

Inspection star ratings based on the ndings from on-site inspections conducted by state survey

agencies to assess practices to ensure the safety of residents.

10

Facilities receive a lower star

rating if they have more identied deciencies and if these problems persist upon follow-up visits.

Star ratings are assigned on a curve, and so the 20 percent of facilities in each state with the worst

inspection ratings are assigned one star, and the 10 percent of facilities with the best inspection

ratings in each state are assigned ve stars.

•

Stang star ratings based on nursing facilities’ reported hours of registered nurse and total nurse

stang, which includes registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certied nurse assistants.

After adjusting for dierences in resident acuity, facilities with higher stang hours per resident

day relative to other facilities receive higher star ratings. Historically, nursing facilities self-reported

stang data to CMS, but since 2016, CMS has required nursing facilities to submit stang data

through an auditable payroll-based journal (PBJ) system that is more accurate. CMS began using

PBJ data for star ratings in 2018. In 2022, CMS began using the PBJ data to include additional

measures of sta turnover and weekend stang in Care Compare (CMS 2022a). These additional

measures are not included in our analyses of 2019 stang ratings.

•

Quality star ratings based on performance on a range of measures used to assess quality of care

for short-stay and long-stay nursing facility residents. Many of the measures are calculated using

data from the Minimum Data Set, which collects information on all nursing facility residents. In 2019,

CMS added several additional measures based on Medicare fee-for-service claims data, which are

included in our analysis (CMS 2019). Some of these claims-based measures, such as hospitalization

and emergency department visit rates, include patients dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid

because Medicare is the primary payer for hospital care. However, these measures do not include

patients who are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, including plans intended to integrate care for

dually eligible patients.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

36

March 2023

Eects of COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate

eect on nursing facilities and their residents. Although

nursing facility residents account for less than 1 percent

of the U.S. population, they have accounted for about

15 percent of COVID-19 deaths as of December 2022

(CMS 2022b).

While the level of community spread is the primary

contributor to the rate of COVID-19 infections in

nursing facilities, the pandemic has also exposed

and exacerbated long-standing nursing facility quality

issues (GAO 2022). A low number of direct care sta

per resident and the use of shared rooms have been

associated with rates of COVID-19 transmission

and death (Harrington et al. 2020a, Li et al. 2020).

Because Medicaid-covered residents are more

likely to reside in facilities with these characteristics,

studies have found that these residents have been

disproportionately aected by the pandemic (Weech-

Maldonado et al. 2021).

As discussed previously, the COVID-19 pandemic has

also led to declines in nursing facility occupancy rates,

which have created nancial challenges for facilities

because of their xed overhead and capital costs.

Although some of the declining occupancy is due to

an acceleration of the shifting patterns for post-acute

care and LTSS that began before the pandemic,

some changes in the occupancy have been driven by

pandemic-specic factors, such as the high death rate

of nursing facility residents.

In response to lower occupancy rates, nursing facilities

have also decreased stang levels. For example,

between January and September 2020, the number

of direct care hours declined 9.8 percent, which was

commensurate with the decline in nursing facility

residents (Werner and Coe 2021). However, as use of

nursing facility care begins to recover from pandemic

lows, some facilities have reported challenges rehiring

sta because of increased labor costs, and without

sucient sta, facilities cannot use all available beds

(CLA 2023).

A variety of state and federal policy changes have

supported nursing facilities during the COVID-19 public

health emergency. For example, the Coronavirus Aid,

Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act, P.L.

116-136) created a time-limited provider relief fund

to oset immediate losses and also provided grants

to states that some have used to increase Medicaid

payment rates (MACPAC 2021a). In addition, CMS

has authorized a number of temporary waivers of

regulatory requirements for nursing facilities, including

allowing nursing facilities to be paid Medicare’s higher

SNF rate for long-stay residents with acute care

needs without requiring a prior hospital stay. These

temporary changes have helped most nursing facilities

manage the disruption in their nances so far, but many

providers are concerned about their nancial viability

after these policies expire (CLA 2023, 2022a).

Policymakers are also using early lessons from the

pandemic to consider a variety of permanent nursing

facility regulatory and payment reforms. In 2022, the

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and

Medicine released a report recommending a variety

of reforms to CMS’s oversight of nursing facilities

and changes to Medicare and Medicaid policies.

Notably, the report calls for greater transparency and

stronger evaluations of Medicaid nursing facility rates,

which align with the Commission’s recommendations

discussed later in this chapter (National Academies

2022).

Medicaid Payment Policies

States have considerable exibility to set Medicaid

nursing facility payment rates and methods. MACPAC’s

analyses of these policies have found wide variation

in the types of payments that states make, how these

payments are nanced, and how Medicaid payments

compare to nursing facility costs.

Federal Medicaid payment

requirements

Nursing facility services have been a required Medicaid

benet since the program’s enactment in 1965, but

Congress has made several changes over time to the

rules governing how states pay providers. The original

statute had few limitations, but in 1972, Congress

required that states pay on a reasonable cost-related

basis, similar to Medicare, because of concerns that

states were overpaying providers (Committee on

Finance 1972).

11

In 1980, the Boren amendment to

the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1980 (P.L.

96-499) removed this requirement and instead required

Medicaid nursing facility payments to be “reasonable

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

37

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

and adequate to meet the costs which must be incurred

by eciently and economically operated facilities in

order to provide care and services in conformity with

applicable state and federal laws, regulations, and

quality and safety standards.” To help states meet

this requirement, the Boren amendment also required

nursing facilities to submit uniform Medicaid cost reports.

The Boren amendment was dicult to implement and

led to a number of provider lawsuits. CMS never formally

dened an “ecient and economically operated” facility,

so each state developed its own method to comply with

this requirement. In 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled

in Wilder v. Virginia Hospital Association that the Boren

amendment created a privately enforceable right for

providers, which led to a growth of lawsuits challenging

provider payment rates and the methods that states had

used to develop them (Wiener and Stevenson 1998).

12

In 1996, Congress repealed the Boren amendment and

gave states additional exibility to set their own payment

rates as long as they developed them using a public

process (§1902(a)(13)(A) of the Act).

A separate Medicaid statutory provision, Section

1902(a)(30)(A) of the Act, still requires Medicaid

payment policies to be consistent with the principles

of eciency, economy, quality, and access to care.

13

In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Armstrong v.

Exceptional Child Center, Inc. that providers no longer

have a right to sue in federal court to enforce these

Medicaid payment requirements, so now they can only

be enforced by CMS.

14

Types of Medicaid payments to nursing

facilities

In 2019, nursing facilities were paid approximately

$66.5 billion for care to Medicaid-covered residents

(Figure 2-3). The two main categories of payment

are base payments, which are typically paid on a per

diem basis for a specic resident, and supplemental

payments, which are generally paid in a lump sum for a

xed period of time. Most payments are base payments

made through the fee-for-service (FFS) delivery

system, but a growing share of Medicaid payments

to nursing facilities are made through managed care

and supplemental payments. In the following sections,

we discuss each of these types of payments in more

detail as well as the limitations of available data for

measuring these payments.

FIGURE 2-3. Base and Supplemental Payments to Nursing Facilities, 2019

FFS and managed care

base payments paid by

residents (estimate),

$6.1 billion,

9%

Supplemental payments,

$3.4 billion,

5%

Managed care

payments paid

by state,

$19.4 billion,

29%

FFS base

payments

paid by state,

$37.6 billion,

57%

Notes: FFS is fee for service. Resident contributions to their share of cost are estimated based on the dierence

between allowed payment rates and actual Medicaid payment amounts in states with available data.

Sources: MACPAC, 2022, analysis of CMS-64 net expenditure data and the Transformed Medicaid Statistical

Information System (T-MSIS).

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

38

March 2023

FFS base payments. Medicaid programs typically

pay nursing facilities a daily rate for Medicaid-covered

residents according to a state fee schedule. Currently,

most states set Medicaid nursing facility payments

based on the costs for various cost centers, such as

direct care (i.e., medical supplies and wages of sta

providing direct care), indirect care (e.g., the costs of

social services and patient activities), administration,

and capital. However, Medicaid payments are not

intended to cover all costs for all facilities because

states set limits on which costs are allowable and set

ceilings on the amount of costs that can be reimbursed

for particular cost centers (e.g., a xed percentage

of the median or average costs for a particular cost

center among similar facilities in the state). Less

than a third of states use a price-based method to

set payments prospectively based on historic costs

adjusted for ination and other factors (MACPAC

2019a, 2019b).

The base payments that states pay are reduced by

resident contributions to their cost of care, which are

paid to the facility directly. Based on our analysis of

claims data in the Transformed Medicaid Statistical

Information System (T-MSIS), resident contributions

to their cost of care accounted for about 10 percent of

base payments to nursing facilities in 2019 (MACPAC

2023a).

Managed care base payments. In 2019, 24 states

paid for some or all nursing facility care through

managed care organizations, up from just 8 states

in 2004. Most states with managed LTSS (MLTSS)

include full coverage for nursing facility services,

although some states carve out long-stay nursing

facility residents from some programs (Dobson et al.

2021, Lewis et al. 2018).

In April 2016, CMS established a new option for

states to direct managed care plans to pay particular

types of providers according to specied rates or

methods, which is referred to as “directed payments.”

Based on MACPAC’s review of directed payment

arrangements approved as of December 31, 2020, 14

states established minimum fee schedules for nursing

facility services provided in managed care (typically

no less than the Medicaid FFS rate), and 6 states

required managed care plans to increase payments

to nursing facilities by a xed amount above base

payment rates, similar to supplemental payments in

FFS (MACPAC 2022a).

Managed care payments to nursing facilities are also

subject to post-eligibility treatment of income rules,

but information on resident contributions to their cost

of care is not available for all states. For example,

in our analyses of 2019 T-MSIS data, ve states

with MLTSS reported managed care base payments

paid by the state but did not report the total allowed

amount, after accounting for resident contributions

to their share of cost, and so we could not include

managed care payments in these states in our

analyses (MACPAC 2023a).

The limited data available on managed care payments

to nursing facilities suggest that they are similar to

FFS in many states. In the four states with MLTSS that

we interviewed in 2020 (Kansas, New York, Rhode

Island, and Wisconsin), managed care plans all paid

nursing facilities according to FFS rates and methods.

Many states had directed payment arrangements

that required plans to pay facilities’ FFS rates, but

plans also noted that it was administratively easier to

do so. Because many managed care plans relied on

state rate setting methods to set their own rates, the

stakeholders we interviewed noted the need for states

to maintain their FFS rate setting capacity even after

moving to MLTSS (MACPAC 2020a).

Supplemental payments. In 2019, 23 states made

a total of $3.4 billion in supplemental payments to

nursing facilities, which accounted for approximately

5 percent of total nursing facility payments. The use

of supplemental payments varies widely by state: 27

states and the District of Columbia did not make any

supplemental payments, and 6 states made payments

that were more than 30 percent of total FFS Medicaid

payments to nursing facilities (MACPAC 2020b).

Medicaid FFS base payment rates and supplemental

payments cannot exceed the upper payment limit

(UPL), which is an estimate of what Medicare would

have paid for the same service in the aggregate.

15

States are required to submit provider-level

information on base and supplemental payments to

CMS annually to demonstrate compliance with these

UPL requirements (CMS 2022c). When calculating the

UPL, states are supposed to account for dierences

in resident acuity and dierences in services that

Medicaid and Medicare cover; nevertheless, states

and CMS still face challenges accurately calculating

the UPL because Medicaid and Medicare payment

rates are not directly comparable (CMS 2022c).

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

39

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

MACPAC’s review of these UPL demonstration data

found several discrepancies between the amount

of payments reported on UPL demonstrations and

the amount of payments claimed by states on CMS-

64 reports in the Medicaid Budget and Expenditure

System (MBES), which is the ocial record of actual

Medicaid spending.

16

CMS is currently implementing

a new process for states to report provider-level

supplemental payment data through MBES, which will

hopefully help improve the reliability of these data in

future years (CMS 2021).

Financing of Medicaid payments

Similar to other Medicaid payments, states and

the federal government jointly nance Medicaid

nursing facility payments according to the state’s

federal matching assistance percentage (FMAP).

The non-federal share of Medicaid payments can

be nanced by state general funds, provider taxes,

and intergovernmental transfers (IGTs) or certied

public expenditures (CPEs) from local governments,

including publicly owned nursing facilities.

State use of nursing facility provider taxes has grown

in recent years, from 22 states in 2004 to 45 states in

2019 (Giord et al. 2019). States are allowed to use

provider taxes to nance their Medicaid programs

as long as the taxes are imposed on a broad base

of providers (i.e., not just providers who serve a high

share of Medicaid patients), are uniformly applied

based on a common tax basis (e.g., provider revenue

or the number of certied nursing facility beds), and

do not guarantee that providers are paid back the

amount that they contribute in taxes. In practice, many

states use the increased federal funding generated

by provider taxes to increase Medicaid payments,

which is permissible as long as the tax does not

exceed 6 percent of net patient revenue for the class

of providers. Many states impose taxes up to this

maximum allowable amount, and in 2019, 22 states

had nursing facility provider taxes between 5.5 and 6

percent of provider revenue (KFF 2020).

17

IGTs and CPEs are commonly used to nance nursing

facilities that are publicly owned, which accounted

for about 5 percent of all nursing facilities, according

to Medicare cost reports in 2019. However, in some

states, the number of facilities that are classied

as publicly owned for Medicaid purposes is much

higher than the number on Medicare cost reports

because of complex ownership arrangements between

public hospitals and privately operated nursing

facilities. Specically, in some states, it is common

for public hospitals to buy or lease privately operated

nursing facilities so that these facilities can receive

IGT-nanced supplemental payments targeted to

government-owned facilities. For example, in Indiana,

90 percent of nursing facilities in the state received

supplemental payments targeted to government-

owned facilities in 2019, including 181 facilities that

were classied as privately owned on Medicare cost

reports (MACPAC 2023b). Indiana reported more than

$1 billion in nursing facility supplemental payments in

2019, more than any other state, but it is unclear how

much of these payments were retained by nursing

facilities and how much of these payments were

returned to the public hospitals that nanced these

payments (Galewitz 2017).

During interviews with stakeholders about the factors

that aect their nursing facility payment methods,

we learned that state decisions to use supplemental

payments are often aected by the methods that

states use to nance the non-federal share of Medicaid

payments. Although states and nursing facilities

generally preferred that rate increases be implemented

through increases to base payments rather than

supplemental payments, these stakeholders generally

viewed supplemental payments as a better way to

target funding to providers to ensure that they were

paid back the amount that they contributed through

provider taxes or IGTs (MACPAC 2020a).

Base payment rates vary widely

According to our analyses of base payment rates

reported in T-MSIS in 2019, Medicaid nursing facility

payment rates varied widely by state and facility. Even

after adjusting for dierences in the area wage index

and dierences in resident case mix, average state

payment rates ranged from 62 to 182 percent of the

national average. Across facilities within states, we also

observed considerable variation (MACPAC 2023a).

Although Medicaid rates are often lower than costs,

we found that Medicaid payments appeared to exceed

the costs of care in some facilities in 2019 (Figure 2-4).

The median facility had payment rates that were 86

percent of costs. However, about one-fth of facilities

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

40

March 2023

had base payment rates greater than 100 percent of

costs, and 15 percent of facilities had base payment

rates less than 70 percent of costs.

Our estimates of Medicaid payments relative to costs

have several limitations. First, we were not able to nd

reliable data on supplemental payments to providers in

all states. In states in which data were available, they

suggested that these payments can substantially aect

the distribution of Medicaid payments relative to costs

(MACPAC 2023a). Second, we were not able to collect

information on provider contributions to the non-

federal share, which can reduce the net payments that

providers receive. Third, the Medicare cost report data

we used for this analysis does not account for state-

specic dierences in allowable costs or the potential

eects of related-party transactions, which may

inate costs reported on facility-specic cost reports

(Adelberg et al. 2022). Finally, because of the limits of

available data, we were not able to examine payments

relative to costs after the start of the COVID-19

pandemic, which has resulted in increased nursing

facility costs and also increased Medicaid payment

rates in many states.

Using Medicaid Payments

to Improve Quality

Medicaid payment policy has the potential to help

improve quality outcomes and reduce disparities. To

better understand Medicaid’s role, the Commission

has examined how nursing facility stang levels vary

by state, how they relate to Medicaid payment policies,

and which barriers states face in changing payment

policies to promote better outcomes.

FIGURE 2-4. Distribution of Medicaid Base Payment Rates as a Share of Acuity-Adjusted Costs, 2019

5%

10%

19%

25%

22%

12%

7%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

Less than 60

percent

60–69

percent

70–79

percent

80–89

percent

90–99

percent

100–109

percent

Share of facilities

Medicaid allowed amount as a share of acuity-adjusted costs

110 percent

or greater

Notes: Base payment rates include resident contributions to their share of costs. Analysis excludes Alaska, Idaho,

and New Hampshire because of unreliable or missing data. Data on resident contributions to their share of costs were

not available for managed care payments in California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Virginia, and

so only fee-for-service spending is included for these states.

Source: Abt Associates, 2022, analysis for MACPAC of the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System

(T-MSIS), Medicare cost reports, and the Minimum Data Set.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

41

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

Background on stang standards

Although stang levels are just one of many measures

of quality, higher stang levels are associated with

a variety of positive health outcomes and have been

a key area of focus for states during the pandemic.

18

Moreover, because stang levels are primarily

aected by how much facilities pay nurses and nurse

aides (often referred to as “direct care sta”), payment

policy can play an important role in helping to address

this issue.

Nursing facilities are staed by a variety of nurses and

nurse aides with dierent levels of training that provide

direct care, including the following:

•

registered nurses (RNs), who have at least a two-

year degree and are responsible for overseeing

residents’ care;

•

licensed practical nurses (LPNs), who have a

one-year degree and typically provide routine

bedside care (such as taking vital signs); and

•

certied nurse aides (CNAs), who have at least

75 hours of training and generally assist residents

with activities of daily living.

19

Currently, CMS requires facilities have licensed nurse

sta (RNs or LPNs) available 24 hours a day, an RN

available eight hours a day, and a full-time director of

nursing. For a 100-bed facility, this standard equates

to 0.3 hours per resident day (HPRD) of licensed

nurse sta.

In 2001, a CMS stang study found that stang levels

of at least 0.75 HPRD of RN stang and 4.1 HPRD of

total stang of nurses and nurse aides (RNs, LPNs,

and CNAs) were associated with optimal quality. The

study did not nd improvement in quality for facilities

that staed above this level (CMS 2001). Although

some stakeholders have argued that 4.1 HPRD is

too high a standard for most nursing facilities, this

standard continues to be endorsed by a variety of

nursing groups (Schnelle et al. 2016, CGNO 2014).

Yet, according to CMS’s Care Compare website,

approximately 72 percent of nursing facilities had

total stang levels below 4.1 HPRD in 2019. CMS is

currently conducting an updated stang study using

more recent data to inform the development of new

stang standards (CMS 2022d).

CMS assigns star ratings to facilities based on how

their stang levels compare to other facilities. In our

analysis, we examined the share of facilities with one-

or two-star stang ratings, which included facilities

with less than 0.5 HPRD of RN care and 3.6 HPRD of

total stang of nurses and nurse aides in 2019.

State variation in stang levels

Overall, nursing facility stang levels vary widely

across states. For example, in three states (Alaska,

Hawaii, and North Dakota) and the District of

Columbia, fewer than 10 percent of freestanding

nursing facilities had one- or two-star stang ratings

on Medicare.gov Care Compare in 2019, while in

three other states (Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas),

more than 70 percent of facilities had these low ratings

(MACPAC 2022b).

We also found wide state variation in the disparities

between facilities that serve a high share of

Medicaid-covered residents and those that do not.

For example, in 2019, the dierence between the

average stang star rating in the quartile of facilities

that served the highest share of Medicaid-covered

residents was more than one star lower than the

quartile of facilities that served the lowest share of

Medicaid-covered residents in seven states (Kansas,

Illinois, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah,

and Virginia). In comparison, the dierence between

the quartile of facilities that served the highest and

lowest share of Medicaid-covered residents was less

than 0.1 stars in eight states (Arkansas, Delaware,

Mississippi, North Dakota, New Mexico, Oklahoma,

Oregon, and Wyoming) (MACPAC 2023c).

The wide state variation that we observe suggests

a role for state policy. Although some state variation

may be due to factors other than Medicaid, disparities

by payer mix are likely aected by Medicaid payment

policies. Moreover, the fact that some states have

relatively high stang levels and few disparities by

payer mix shows that ensuring adequate stang to

meet the needs of Medicaid-covered residents is an

achievable goal.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

42

March 2023

Relationship between payment rates

and stang

Prior research has suggested that increasing Medicaid

payment rates has the potential to improve stang.

For example, studies of rate increases in California,

Ohio, and Pennsylvania found that they were

associated with improved stang, particularly for RNs

and LPNs (Hackman 2019, Bowblis and Applebaum

2017, Bishop 2014).

However, in our analysis of 2019 data, we did not nd

a clear relationship between Medicaid payments and

stang levels (Table 2-2). Average base payment

rates were higher for facilities with a ve-star stang

rating (the highest) compared with facilities with a one-

star rating (the lowest). However, after accounting for

dierences in facility costs, the Medicaid payment-to-

cost ratio in facilities with ve-star stang ratings was

7 percentage points lower on average than facilities

with a one-star rating.

Average costs are lower in facilities with lower stang

levels in part because these facilities spend less on

sta, which is a substantial component of nursing facility

costs.

20

After estimating what costs would be if facilities

had similar stang levels, the dierence in Medicaid

margins between facilities with low stang levels and

high stang levels narrows, but Medicaid margins are

still higher for facilities with lower stang ratings.

21

Role of Medicaid payment methods

and state stang requirements

In addition to increasing payment rates, states can

also change other policies to encourage facilities to

spend more of the revenue that they receive on sta.

Two approaches that we studied are (1) changing

Medicaid payment methods to incentivize spending

on direct care sta and (2) requiring that facilities

meet minimum stang standards that exceed federal

requirements. To better understand the potential

eects of these policies, we conducted a literature

review of relevant studies published since 2008.

Medicaid payment methods. Examples of Medicaid

payment methods that may promote higher stang

levels include wage pass-through payments that

require facilities to spend a specied portion of the

TABLE 2-2. Average Medicaid Base Payments per Day and Acuity-Adjusted Costs by Five-Star Stang Rating, 2019

Five-star

stang rating

in the CMS

Nursing Home

Quality Rating

System

Number of

facilities in

analysis

Average

Medicaid base

payment rate

per day

Average cost

of care for

Medicaid-

covered

residents

Average

Medicaid base

payment as a

share of costs

Average

Medicaid base

payment as a

share of costs

if facilities

were staed

with at least 3.6

HPRD

All facilities 12,377 $199.74 $237.85 84% 82%

1 star (lowest) 1,701 183.26 209.36 88 83

2 star 3,451 195.71 227.5 4 86 83

3 star 3,739 201.93 243.94 83 82

4 star 2,572 209.66 257.41 81 81

5 star (highest) 831 230.54 286.93 80 80

Notes: CMS is Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HPRD is hours per resident day. The threshold for a three-star

stang rating in 2019 was 3.6 HPRD. Base payments include resident contributions to their share of costs. Average costs

and payments are weighted by the number of Medicaid days in each facility. Alaska, Idaho, and New Hampshire were

excluded from analysis due to data quality issues. The analysis also excluded facilities with missing payment data and

outlier stang costs.

Source: Abt Associates, 2023, analysis for MACPAC of the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS),

Medicare cost reports, the Minimum Data Set, and Medicare.gov Care Compare.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

43

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

Medicaid rate on sta wages, cost-based payment

methods that tie payment rates to spending on direct

care sta, and pay for performance (P4P) incentive

payments that tie payments to meeting stang goals.

Overall, there is limited research available about the

eectiveness of these methods. One multivariate

study using 2002 data found that cost-based payment

methods were associated with both higher RN stang

and higher total stang (Harrington et al. 2007). A

review of wage pass-through policies implemented

between 1996 and 2004 found CNA stang levels

increased in the initial years after implementation

but found no statistically signicant eect on RN or

LPN stang (Feng et al. 2010). Finally, one review

of eight Medicaid P4P programs compared with a

nationwide control group found that only one state had

a statistically signicant eect on stang measures

and that the eects on resident-level outcomes were

also limited (Werner et al. 2013).

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a number

of states made changes to their Medicaid payment

policies related to stang. As of fall 2021, 12 states

increased payments to direct care workers, 1 state

added a new wage pass-through policy, and 4 states

implemented new payment incentives related to

stang since 2020 (MACPAC 2022a).

22

In 2022,

Illinois implemented a new rate increase for CNAs

that was dierent from other policies that we studied

because it targeted higher wages to more experienced

sta to help improve sta retention (IL HFS 2021).

During our interviews, we heard mixed perspectives

about whether states would be able to continue rate

increases in the long term. Some states nanced

temporary rate increases using grants from the $150

billion Coronavirus Relief Fund authorized by the

CARES Act, which can be used only for expenses

incurred during the public health emergency. As a result,

to continue these rate increases after the public health

emergency using Medicaid authorities, these states

would need to provide additional state matching funds.

Minimum stang standards. States can set their

own minimum stang standards that exceed federal

requirements. According to MACPAC’s review of state

stang policies in 2021, 38 states and the District of

Columbia have state minimum stang standards

that exceed the federal requirements of 0.3 HPRD of

licensed nurse sta for a 100-bed facility. However,

state standards vary widely. For example, 9 states

have standards that are less than 2.0 HPRD, and 11

states and the District of Columbia have standards

that are greater than 3.0 HPRD. In addition, states

vary in whether they have specic requirements

for licensed nurse sta or whether the HPRD

requirements apply to all nurses and nurse aides

(including CNAs) (MACPAC 2022b).

Prior research has found that increases in minimum

stang standards are associated with improvements

in stang, particularly for CNAs. For example, an

analysis of new minimum stang requirements

in California and Ohio found a 5 percent increase

in HPRD overall but a reduction in skill mix (i.e.,

the ratio of RNs to all direct care sta) (Chen and

Grabowski 2014).

23

In another study that examined

the eects by payer mix, facilities that served a higher

share of Medicaid patients reported larger increases

in stang, including RN stang, in response to

increases in minimum stang requirements, resulting

in larger gains in other measures of quality of care

(Bowblis 2011).

Several states recently changed their stang

requirements in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In our review of policies enacted as of October 2021,

we identied 10 states that increased minimum stang

standards since 2020. Two states (Maine and New

Jersey) added new minimum wage requirements

specically for direct care sta, a new type of policy

that we did not nd in states before the pandemic

(MACPAC 2022a).

Minimum loss ratio requirements that cap nursing

facility prots and require facilities to spend a

minimum amount on stang are a new policy

approach to promote stang that is being developed

in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York. In

2019, median stang costs as share of nursing facility

revenue were 34 percent but varied widely by state.

Facilities in the 90th percentile of Medicaid-covered

days have higher median stang costs as a share of

revenue (36 percent), which suggests that policies to

increase the share of revenue spent on sta may have

less of an eect on facilities that serve a high share of

Medicaid-coverage residents (Bowblis et al. 2023).

In April 2022, CMS requested information from

stakeholders about raising federal minimum stang

standards, and a new stang study intended to inform

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

44

March 2023

these eorts is underway (CMS 2022d). Although the

relationship between higher stang levels and higher

quality care has been well documented, questions

remain about what an appropriate minimum stang

standard should be. Increasing federal standards

would help improve quality, but it would also likely

result in increased costs for facilities, which may

require some state Medicaid programs to make higher

payments (CLA 2022b).

Challenges changing state payment

methods

Despite the potential for Medicaid payment policies

to help improve the quality of nursing facility care,

progress in developing new payment models has

been relatively slow compared with other provider

types. Between 2014, when MACPAC rst reviewed

FFS nursing facility payment policies, and 2019, when

we updated our compendium, few states made any

substantial changes to their nursing facility payment

methods (MACPAC 2019a). During subsequent

interviews with state ocials, nursing facilities, and

other stakeholders in 2020, we learned that limited

state capacity, industry resistance, and a lack of clarity

about value-based payment goals were the primary

barriers to change (MACPAC 2020a).

Limited state capacity. The state ocials we

interviewed described several limits in their capacity to

make changes to their already complicated nancing

systems. Some states faced reductions in stang to

analyze Medicaid nursing facility FFS rates due to

budget cuts or the expansion of MLTSS. In addition,

states reported losing institutional knowledge because

of sta turnover, which was hard to replace because

Medicaid nursing facility payment policy is so complex.

Some states hire external consultants to support their

capacity when making new reforms, but these states

later reported a similar loss of institutional knowledge

when the consultants who initially designed the

payment system were no longer available to evaluate

future changes to payment policies.

Industry resistance to change. The nursing facility

industry associations that we interviewed were

generally active in lobbying state policymakers

against changes in payment methods that could

create winners and losers among nursing facilities

in their states. Instead, these associations primarily

advocated for increased payment rates because of a

view that state payment rates were too low to cover

costs and concerns that states would cut rates further

for budgetary reasons. In states that did get provider

support for payment changes, state ocials noted

the need to engage stakeholders early and provide

sucient time to prepare for any change.

Lack of clarity about value-based payment goals.

Twenty-ve states had P4P incentive payment

programs in nursing facilities in 2019, but the state

ocials that we interviewed in seven states noted

that P4P programs in their states did not appear

to be particularly eective (MACPAC 2019a). For

example, one state’s program was more than two

decades old, and due to secular trends and federal

policies implemented in recent years, most facilities

had already achieved most of the program’s initial

goals related to reducing survey deciencies and

meeting targets for culture change to promote more

person-centered care. States reported challenges

selecting new measures that were tied to quality

outcomes, such as reductions in rehospitalizations or

improvement in long-stay quality measures, because

of a lack of consensus among stakeholders about how

these quality measures should be dened and how the

targets should be set.

In the states we studied, interviewees did not mention

any eorts to incorporate nursing facilities into

alternative payment models that states were using

for their acute care populations, such as accountable

care organizations. Although stakeholders

acknowledged the high rate of avoidable hospital use

among Medicaid-covered nursing facility residents,

they noted that it was dicult to develop alternate

payment models for residents dually eligible for

Medicare and Medicaid because savings from

reducing hospital use for these residents accrue to

Medicare rather than Medicaid.

We also heard a lack of consensus among

stakeholders about whether a value-based measure

of cost savings is appropriate in assessing value for

nursing facility care because of the risk that facilities

may reduce costs by cutting direct care sta needed

to meet residents’ care needs. One state in our study,

New York, switched from a cost-based payment

method to a price-based system in 2017 to provide

more budget predictability for the state, uniformity

across facilities, and administrative eciency.

Chapter 2: Principles for Assessing Medicaid Nursing Facility Payment Policies

45

Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP

Although the state still sets prices based on prior

year cost reports, the state has less control than it

would in a cost-based system on how facilities spend

the Medicaid revenue that they receive. Recently,

in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, New York

increased state minimum stang standards and added

a new requirement that facilities spend at least 70

percent of their total revenue on direct care, which

are other tools that states can use to address stang

issues in the absence of cost-based payment systems

(Reiland 2022).

Interaction between

Medicare and Medicaid

Payment Policy

Because Medicare is the second-largest payer for

nursing facility care, many of the payment standards

used by Medicare are also used by Medicaid programs.

In addition, because most Medicaid-covered nursing

facility residents are dually eligible for Medicare and

Medicaid, Medicare payment incentives can aect

the care that Medicaid-covered residents receive.

To understand these interactions in more detail, the

Commission has been monitoring the eects of recent

changes to Medicare’s acuity adjustment system and

the ndings of recent evaluations of eorts to reduce

avoidable hospital use for dually eligible residents.

Acuity adjustment changes

In October 2019, Medicare changed the method it uses

to classify SNF patient acuity from Resource Utilization

Group Version IV (RUG-IV) to the Patient-Driven

Payment Model (PDPM). Under the RUG-IV model,

nursing facilities were incentivized to provide additional

therapy services because the measure of a resident’s

therapy care needs was predominately determined by

the number of minutes of therapy the facility provided.

PDPM corrects these incentives by setting a case-

mix weight based on a resident’s primary diagnosis.

The case-mix weights for PDPM were developed

over several years but used data only for Medicare-

covered nursing facility residents, not Medicaid-covered

residents (Acumen 2018).

As of July 2019, 34 states used RUG-based payment

methodologies for Medicaid-covered residents, and

so Medicare’s change has prompted many states to

reassess their acuity-adjustment methods (MACPAC

2019a). As of October 1, 2023, CMS will no longer

collect information needed to determine RUG case-

mix groups on the Minimum Data Set, which will

make it more dicult for states to continue RUG-

based methods. CMS has provided states the option

of requiring facilities to report additional information

through a state supplement to the Minimum Data Set

until September 30, 2025, if needed to help ease the

transition (CMS 2022c).

Because PDPM was not developed to measure their

acuity or resource use, some components of PDPM

are not a good measure of the care needs for long-

stay residents. The PDPM includes ve components

for measuring the acuity of an SNF patient: nursing,

physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech-

language pathology, and non-therapy ancillary. Although

the nursing component is similar to the previous RUG-

IV model, the therapy components are dierent and

substantially overstate the needs of long-stay residents

(Abt Associates 2020). Because of the challenges

adapting the PDPM therapy components to long-stay

residents and the fact that most therapy services are

not included in the Medicaid nursing facility benet,

CMS issued guidance in 2022 recommending that

states exclude the therapy portions of the PDPM from

their Medicaid payment methods (CMS 2022c).

Another limitation of PDPM is that the underlying data

used to develop the nursing component were based

on a 2007 study of nursing sta time, the latest that

CMS has completed. Some stakeholders have noted

the need for an updated time study that reects current

stang patterns at high-quality facilities and also

considers the unique needs of long-stay Medicaid-

covered residents (Harrington et al. 2020b).

Incentives to reduce avoidable

hospital use

About one-quarter of nursing facility residents are

transferred to hospitals each year, and many of these

hospitalizations could be avoided if residents received

quick diagnoses and treatments in nursing facilities.

Overall, avoidable hospital use for nursing facility