DHS’ Process for

Responding to FOIA and

Congressional Requests

July 23, 2020

OIG-20-56

J

uly 23, 2020

DHS OIG HIGHLIGHTS

DHS’ Process for Responding to FOIA and

Congressional Requests

July 23, 2020

Why We

Did This

Review

In response to a request from the

Senate Homeland Security and

Governmental Affairs Committee,

Permanent Subcommittee on

Investigations, we conducted a

review of DHS’ handling of

Freedom of Information Act

(FOIA) requests and

congressional requests directed

to the DHS Office of the

Secretary — specifically, the

DHS Secretary and Deputy

Secretary.

What We

Recommend

This is a descriptive report and

contains no recommendations.

For Further Information:

Contact our Office of Public Affairs at (202) 981-

6000, or email us at

What We Found

DHS outlines its process for responding to FOIA and

congressional requests in internal policy and

procedure documents, which include timeliness goals

(some of which are based on statutory timelines) and

other guidance for searching for, collecting,

processing, and producing responsive materials.

Regarding FOIA requests, while DHS generally met

deadlines for responding to simple FOIA requests, it

did not do so for most complex requests. A

significant increase in requests received, coupled

with resource constraints, limited DHS’ ability to

meet production timelines under FOIA, creating a

litigation risk for the Department. However, despite

the limitations, DHS FOIA response times are better

than the averages across the Federal Government.

Additionally, DHS has not always fully documented

its search efforts, making it difficult for the

Department to defend the reasonableness of the

searches undertaken.

With respect to responding to congressional requests,

DHS has established a timeliness goal of 15 business

days or less. However, we found that, on average, it

took DHS nearly twice as long to provide substantive

responses to Congress, with some requests going

unanswered for up to 450 business days. Further,

DHS redacted personal information in its responses

to congressional committee chairs even when

disclosure of the information was statutorily

permissible.

DHS Response

DHS acknowledged FOIA backlogs remain a problem,

despite increasing the number of requests processed.

DHS stated its process for responding to

congressional requests varies and that its redactions

are appropriate.

www.oig.dhs.gov OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Table of Contents

Introduction.................................................................................................... 2

Background .................................................................................................... 2

Results of Review ............................................................................................ 5

Resource Constraints Have Limited DHS’ Ability to Respond to FOIA

Requests Timely .................................................................................... 6

Components and OCIO Did Not Consistently Complete FOIA Search

Forms to Indicate They Conducted a Reasonable Search ..................... 11

DHS Often Exceeded Its Timeliness Goal When Responding to

Congressional Requests and Redacted Information ............................. 12

Appendixes

Appendix A: Objective, Scope, and Methodology ................................. 17

Appendix B: DHS Comments to the Draft Report ................................. 19

Appendix C: Information Exempt from Disclosure under FOIA ............. 23

Appendix D: DHS Privacy Office FOIA Request Process and DHS

Congressional Request Process ……………………………......................... 24

Appendix E: FOIA Litigated Cases ........................................................ 26

Appendix F: Major Contributors to This Report .................................... 28

Appendix G: Report Distribution ......................................................... .29

Abbreviations

ALJ Administrative Law Judge

DOJ Department of Justice

ESEC External Liaison Team

FOIA Freedom of Information Act

OCIO Office of Chief Information Officer

OGC Office of General Counsel

OIG Office of Inspector General

OLA Office of Legislative Affairs

PSI Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

SOP Standard Operating Procedure

U.S.C. United States Codes

www.oig.dhs.gov 1 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Introduction

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

1

and congressional oversight serve to

promote transparency in, and facilitate oversight of, the Federal Government.

Agency responses to these requests provide the public with important

information about their government and play a vital role in our democracy. As

the third largest Federal department, composed of 22 components with various

law enforcement and national security missions, the Department of Homeland

Security and its operations are the subject of intense public and congressional

interest. DHS receives the most FOIA requests of any Federal agency,

2

and

some 86 congressional committees and subcommittees have asserted some

form of jurisdiction or oversight of it.

3

As a result, DHS must ensure it has

processes in place to respond to these requests in a timely and efficient

manner, in compliance with laws, regulations, and internal policies.

In response to a request from the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental

Affairs Committee, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, we conducted a

review of DHS’ handling of FOIA requests and congressional requests directed

to the DHS Office of the Secretary — specifically, the DHS Secretary and

Deputy Secretary.

4

Background

The DHS Privacy Office handles FOIA requests directed to the DHS Secretary

and Deputy Secretary; requests directed to the DHS Secretary and Deputy

Secretary by Members of Congress and congressional committees are handled

by the Office of the Executive Secretary, Communications and Operations,

External Liaison Team, as shown in figure 1.

1

5 United States Code (U.S.C.) § 552 (2006 & Supp. IV 2010)

2

Department of Justice Summary of Annual FOIA Reports for Fiscal Year 2019 states that

DHS received 47 percent of all FOIA requests to the Federal government, nearly 200,000 more

than the Federal agency that received the second most requests.

3

On September 4, 2007, then DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff sent a letter to U.S.

Representative Peter King providing a list of 86 committees and subcommittees that claim

jurisdiction over DHS.

4

Our review did not include requests sent directly to DHS components.

www.oig.dhs.gov 2 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Figure 1: Simplified DHS Office of the Secretary Organizational Chart

Source: Office of Inspector General (OIG) based on DHS organizational charts

Requests for Information under FOIA

Congress enacted FOIA to give the public access to information in the Federal

Government. The Supreme Court has explained that “[t]he basic purpose of

FOIA is to ensure an informed citizenry, vital to the functioning of a democratic

society, needed to check against corruption and to hold the governors

accountable to the governed.”

5

In furtherance of this purpose, the Act requires

Federal executive branch agencies, such as DHS and its components, to

respond to a request within 20 business days, and to disclose responsive

records unless such records are protected from disclosure by one or more

enumerated exemptions.

6

If an agency fails to respond to a request within the allotted time, the requester

may file a lawsuit in Federal court. If a requester is unsatisfied with the

agency’s initial response to the request, the requester must first file an appeal

with the agency before seeking relief in Federal court. At DHS, if a requester

appeals the initial response, the matter is referred to an Administrative Law

5

NLRB v. Robbins Tire & Rubber Co., 437 U.S. 214, 242 (1978)

6

5 U.S.C. § 552(b). Appendix C provides information on the nine FOIA exemptions.

www.oig.dhs.gov 3 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Judge (ALJ) from the United States Coast Guard, who adjudicates all such

appeals by conducting an independent review of the request and response and

issuing a decision to the requester.

7

FOIA requires decisions on appeals be

issued within 20 business days.

8

If the appeal is not favorable to the

requester, or takes longer than 20 business days to decide,

9

the requester may

file a lawsuit in Federal court.

10

At DHS, the FOIA Operations and Management Team (FOIA Team) within the

Privacy Office processes FOIA requests submitted to the Privacy Office and 14

other DHS Headquarters offices.

11

To process and respond to requests, the

FOIA Team takes the steps detailed in appendix D. The FOIA Team is also

responsible for providing regulatory and policy guidance to DHS on compliance

with FOIA.

12

Generally, the FOIA Team’s guidance reiterates Department of

Justice (DOJ) Office of Information Policy’s guidance and information from the

FOIA.gov website.

Requests for Information from Congress

Congress enjoys broad authority to obtain information. Although there is no

express provision of the Constitution or specific statute authorizing the

conduct of congressional oversight or investigations, the Supreme Court has

established that such power is essential to the legislative function.

13

7

The ALJ’s independent review includes review of the entire administrative file before the

agency at the time of the determination, including (if applicable) any correspondence between

the agency and the requester (e.g., narrowing the scope of the request), the search conducted

by the agency, the search results, the FOIA exemptions applied by the agency, and the final

agency response.

8

5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(A)(ii)

9

5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(A)

10

5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B)

11

The 14 other DHS Headquarters offices are: Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office;

Management Directorate; Military Advisor’s Office; Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties;

Office of Health Affairs; Office of Legislative Affairs; Office of Operations Coordination; Office of

Partnership and Engagement; Office of Public Affairs; Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans;

Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman; Office of the Executive

Secretary; Office of the General Counsel; and Office of the Secretary.

12

DHS Policy Directive 262-11: Freedom of Information Act Compliance

13

Watkins v. United States, 354 U.S. 178, 187 (1957) (emphasizing the “...power of the

Congress to conduct investigations is inherent in the legislative process. That power is broad.

It encompasses inquiries concerning the administration of existing laws as well as proposed or

possibly needed statutes.”); Eastland v. United States Servicemen’s Fund, 421 U.S. 491, 504

(1975) (stating the scope of Congress’ power of inquiry is as penetrating and far-reaching as the

potential power to enact and appropriate under the Constitution).

www.oig.dhs.gov 4 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Within DHS, the External Liaison Team (ESEC)

14

in the Office of the Executive

Secretary’s Communications and Operations group manages external

correspondence addressed to the Secretary and Deputy Secretary, including

congressional correspondence. The Office of Legislative Affairs (OLA) receives

the congressional correspondence and sends it to ESEC to coordinate the

response. If the response involves information from one or more DHS

components, ESEC tasks the appropriate component(s) for a response. The

component drafts the response, acquires all necessary internal clearances,

15

and sends the response back to ESEC to coordinate clearance within DHS.

16

Once the component or ESEC has prepared a response, ESEC acquires

clearances with DHS’ Office of Management, Office of Policy,

17

OLA, and Office

of General Counsel (OGC). ESEC then packages the response for signature.

ESEC’s internal policy provides 5 to 15 business days to respond to

congressional requests, depending on whether a request is deemed “urgent” or

“routine.” If a component head is to provide the response, the component

releases the cleared response to Congress. If the Secretary or Deputy Secretary

is to provide the response, DHS OLA releases the cleared response to Congress.

Appendix D includes a flowchart showing this process.

Results of Review

While DHS generally met statutory deadlines for responding to simple FOIA

requests, it did not do so for most complex requests.

18

The FOIA Team

experienced significant increases in the number of requests received but FOIA

Team managers said they have limited staff to handle the volume, making it

difficult to meet the 20-business-day requirement. In addition, the FOIA Team

processed requests for 14 other DHS Headquarters offices, but did not track

and could not easily identify the number of requests it processes for each office

14

We use “ESEC” to refer to the External Liaison Team for the purposes of this report.

15

Clearance is the process by which relevant staff and senior leadership reviews and concurs

with materials intended for release.

16

In comments to our draft report, DHS stated that ESEC receives congressional

correspondence through several sources, such as DHS components or external stakeholders,

and via other means, such as email or United States Postal Service, not just through OLA. In

addition, DHS clarified that the component, not ESEC, coordinates clearance with DHS’ Office

of Management, Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans, Office of Legislative Affairs (OLA), and

General Counsel (OGC) prior to sending the response back to ESEC. Because these changes

appear to post-date our fieldwork, we are unable to independently verify them.

17

The Office of Policy has since been renamed the Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans.

18

A simple request is a FOIA request that an agency anticipates will involve a small volume of

material or can be processed relatively quickly. A complex request typically seeks a high

volume of material or requires additional steps to process, such as the need to search for

records in multiple locations. See https://www.foia.gov/glossary.html.

www.oig.dhs.gov 5 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

so it could seek reimbursement. The FOIA Team also did not have sufficient

electronic storage space to receive and process all responsive documents,

which delayed several FOIA responses, in many cases by more than a year.

Additionally, although reliant on DHS components and the Office of Chief

Information Officer (OCIO) to conduct searches and document the methods

used to complete those searches, the FOIA Team did not consistently receive

completed search forms to indicate a reasonable search was conducted.

However, despite the limitations and as set forth below, DHS FOIA response

times are better than the averages across the Federal Government.

When responding to congressional requests, we found DHS often exceeded its

timeliness goals and did not consistently provide interim responses. Further,

DHS redacted personal information in its responses to congressional committee

chairs that was eligible for release under DHS policy.

Resource Constraints Have Limited DHS’ Ability to Respond to

FOIA Requests Timely

Past and current resource limitations have delayed DHS responses to FOIA

requests. The FOIA Team has faced challenges in timely processing due to a

sharp increase in requests in fiscal years 2017 and 2018, and limited staff to

handle the number of requests they receive. The FOIA Team also processes

requests for 14 other DHS Headquarters offices, which increases the workload.

However, the FOIA Team does not track and cannot easily identify the number

of FOIA requests it processes for each office. As a result, it does not exercise its

ability to seek reimbursement from the offices for the services it provides. We

also found several FOIA responses had been delayed, in many cases by more

than a year, because the FOIA Team did not have sufficient electronic storage

space to accommodate the responsive emails.

Limited Staffing and Increases in FOIA Requests Hindered the FOIA

Team’s Ability to Meet Statutory Response Timeframes

According to FOIA, an agency must release records within 20 business days;

however, with written notice to the requester, an agency may automatically

extend the timeframe by an additional 10 business days for complex requests

requiring the agency to:

x search for and collect requested records held by an office different than

the one processing the request;

x examine a voluminous amount of records; or

www.oig.dhs.gov 6 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

x consult with other agencies with a substantial interest in the

determination of the request.

19

Even with the 10-day extension, the DHS FOIA Team consistently did not meet

the statutory response time for complex requests for FYs 2013 to 2018. The

FOIA Team took an average of 85 days to process complex requests during this

period, peaking at an average of 99 days in FY 2018. Nevertheless, the DHS

FOIA Team’s processing averages have been consistently lower than the

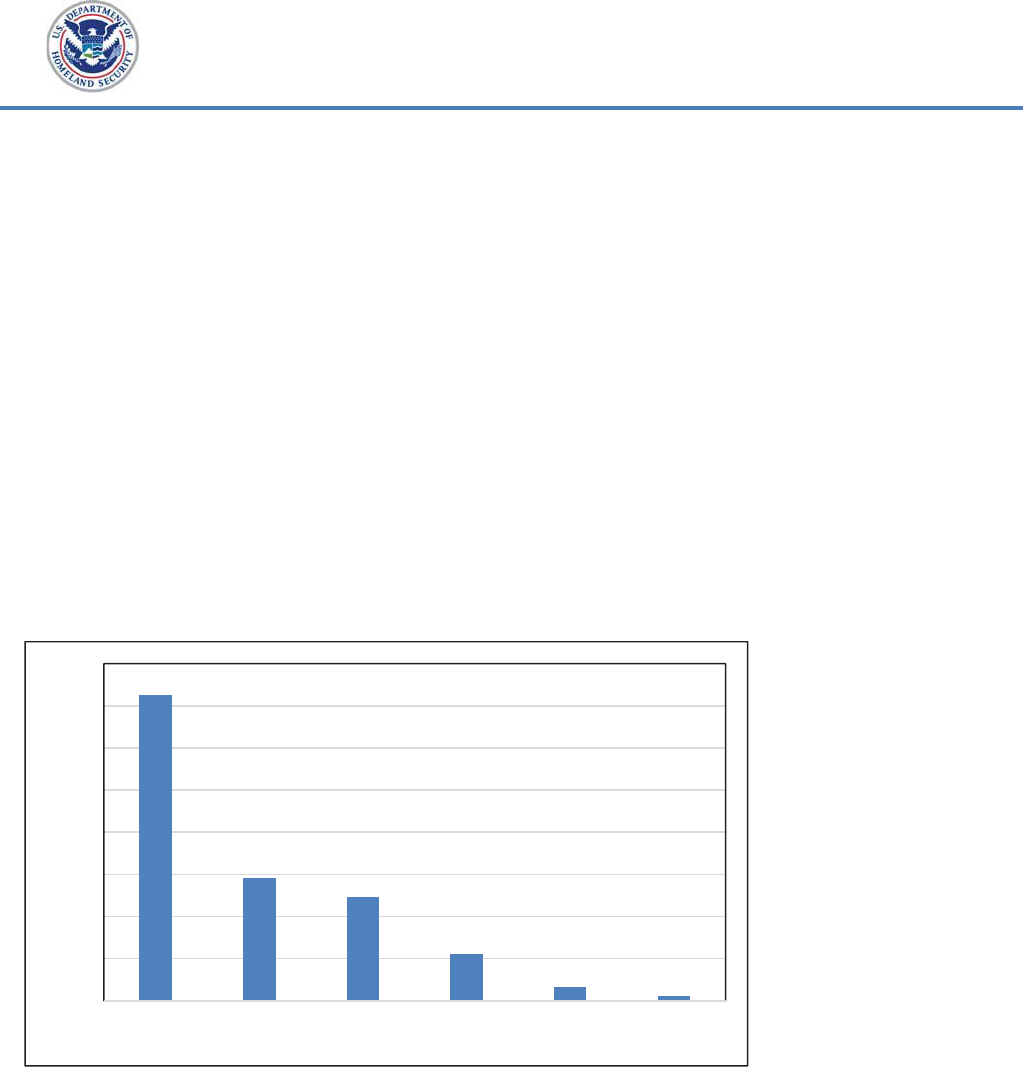

averages across the Federal Government (figure 2).

Figure 2: Average Business Days for FOIA Team to Respond to FOIA

Requests Compared to Federal-wide*, FYs 2013–2018

16

5

8

7

4

8

63

82

79

88

96

99

21

21

23

28

28

26

123

119

122

128

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

FY 2013 FY 2014 FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 FY 2018

Privacy Office: Simple Privacy Office: Complex

Fed-Wide: Simple Fed-Wide: Complex

Source: OIG analysis of FOIA.gov data

* DOJ, Summary of Annual FOIA Reports for Fiscal Year 2016. DOJ did not report the average

number of days for complex requests in its FY 2017 or FY 2018 reports, and we could not

calculate it based on available data.

When Federal agencies do not respond to FOIA requests within statutory

timeframes, a requester may file suit against the agency. We reviewed all 62

litigation cases the FOIA Team had from October 2014 to May 2018

20

and

determined in the majority of cases, 49 of 62 FOIA requesters (79 percent)

alleged lack of timeliness as the reason for litigation.

21

These requesters waited

23 to 478 business days from when they submitted the initial FOIA request to

when they filed the litigation. The reasons for litigation in the remaining 13

19

5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(6)(B)

20

The FOIA Team tracks litigation cases against its office and the 14 DHS Headquarters offices

for which it processes FOIA requests.

21

See appendix E for all 62 litigated cases.

www.oig.dhs.gov 7 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

cases included challenges to the adequacy of the searches performed,

application of exemptions, and failure to approve expedited processing.

According to FOIA Team managers, they do not have enough staff to handle the

number of FOIA requests they receive, which increased 125 percent in FY

2017, resulting in difficulty meeting the 20-business-day requirement. FOIA

Team managers have requested additional staff, but the FOIA Team does not

have its own line item in DHS’ budget; rather, they receive funds from the

Privacy Office. According to the Deputy Chief FOIA Officer, since FY 2017, he

has been able to hire contractors with funds available from the attrition of

Federal employees and funds received from components for their use of

FOIAXpress, the system used by DHS to track FOIA requests. Despite these

efforts, the total number of staff has not increased at a rate commensurate

with the increase in FOIA requests received, as shown in table 1.

Table 1: Total FOIA Requests Received and Total Full-Time and Full-Time

Equivalent FOIA Staff, FYs 2013–2018

Fiscal Year Number of FOIA

Requests Received

Full-Time and Full-Time

Equivalent FOIA Staff

2013 798 16

2014 705 17

2015 649 18.6

2016 599 16.58

2017 1,348 19.25

2018 1,448 25

Source: OIG analysis of FOIA.gov data

Based on this data, between FYs 2013 and 2016, the average ratio of FOIA staff

members to FOIA requests was approximately 1:40; for FYs 2017 and 2018,

that ratio was 1:64.

The FOIA Team Did Not Track and Seek Reimbursement for Work

Performed on Behalf of 14 Other DHS Headquarters Offices

In addition to processing FOIA requests the Privacy Office receives, the FOIA

Team also processes requests for 14 other DHS Headquarters offices. The

FOIA Team is authorized to receive reimbursement for this work from the other

offices, but does not do so, in part because it does not track and cannot easily

identify the number of FOIA requests it processes for each office.

According to Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-11, Preparation,

Submission, and Execution of the Budget, agencies can perform reimbursable

www.oig.dhs.gov 8 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

work for other agencies under the Economy Act.

22

The Economy Act authorizes

the head of a major organizational unit to place an order with another major

organizational unit within the same agency for services.

23

The service-

providing unit — the FOIA Team, in this case — can charge the ordering units

— the 14 DHS Headquarters offices — the actual cost of the services provided.

To receive reimbursement for the FOIA requests it processes for the 14 other

DHS Headquarters offices, the FOIA Team would need to identify the costs

associated with processing the requests. However, the FOIA Team does not

track requests processed for the individual offices, and instead categorizes all

requests it processes as a “Privacy Office” request in FOIAXpress. As a result,

to identify the specific DHS Headquarters office for which a particular request

was processed, the FOIA Team needs to open each Privacy Office request

individually, which is labor intensive and inefficient. Consequently, the FOIA

Team does not calculate the cost of the services it provides to each office and

has not sought the reimbursement it might otherwise collect to address some

of its resource limitations.

24

DHS Did Not Allot Sufficient Electronic Storage Space to Handle Its FOIA

Processing Needs

FOIA states that in responding to a request for records, “[a]n agency shall make

reasonable efforts to search for the records in electronic form or format....”

25

The DHS FOIA Team relies on OCIO to search for and collect emails responsive

to FOIA requests.

26

Although OCIO completes these searches, in the past the

FOIA Team lacked the necessary electronic storage space to receive all

responses, which delayed the processing of these FOIA requests.

Until September 2018, when OCIO completed a search in response to a FOIA

request, it informed the FOIA Team of the aggregate file size of the collected

responsive emails, at which point the FOIA Team would determine whether it

had the storage capacity on its server to receive the responsive emails. In

22

Office of Management and Budget Circular A-11, Preparation, Submission, and Execution of

the Budget, 20.12, June 2019

23

31 U.S.C. § 1535

24

Although providing no monetary reimbursement, two offices have assigned a staff member

each to assist in processing FOIA requests and alleviate some of the FOIA Team’s workload.

25

5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(3)(C)

26

DHS Policy Directive 141-01, Records and Information Management, (August 11, 2014)

established the policy for managing such records, requiring OCIO “…provide for the seamless

capture and storage of electronic records and associated metadata in DHS enterprise–wide

systems and applications.”

www.oig.dhs.gov 9 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

September 2018, however, the FOIA Team reached capacity on its server

27

and

could not take additional responsive emails from OCIO, including eight pending

transfers as shown in table 2, until the FOIA Team created additional space by

expanding its server capacity or deleting records already provided to

requesters. Because the FOIA Team did not have sufficient electronic storage

space to receive the responsive emails, the emails stayed in OCIO instead of

being processed and produced to the FOIA requester. As the data in table 2

shows, without adequate server capacity to receive responsive emails from

OCIO, the FOIA Team exceeded statutory deadlines in many instances by more

than 200 business days.

Table 2: Pending Transfers from OCIO, as of September 25, 2018

Date of Request Size of File Elapsed Business Days

June 23, 2017 40 GB 316

June 29, 2017 36 GB 312

July 5, 2017 48 GB 309

July 19, 2017 64 GB 299

September 5, 2017 7 GB 266

October 13, 2017 25.4 GB 239

December 4, 2017 44 GB 205

January 31, 2018 37.3 GB 166

Source: OIG analysis of OCIO data and discussions with FOIA Team personnel

Despite the absence of adequate server space, the FOIA Team took some steps

to try to make progress on these FOIA requests. For instance, in one case, the

FOIA Team worked with the requester and OCIO over several months to narrow

the scope of the request until the volume of responsive emails was small

enough to fit on the FOIA Team’s server.

As of August 2019, the FOIA Team upgraded its servers and was able to add

additional electronic storage space. According to a Privacy Office official, the

FOIA Team is no longer having issues accepting responsive emails from OCIO.

The Deputy Chief FOIA Officer said there are plans to move the FOIA Team’s

server to a cloud-based system by March 2020, which would further mitigate

the storage capacity issue.

27

The FOIA Team’s server capacity was six terabytes (TB) as of September 25, 2018. One TB is

equal to 1,000 gigabytes (GB). The FOIA Team updated the server capacity to 10.5 TB as of

August 8, 2019.

www.oig.dhs.gov 10 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Components and OCIO Did Not Consistently Complete FOIA

Search Forms to Indicate They Conducted a Reasonable Search

When responding to a FOIA request, a Federal agency must conduct a

reasonable search for responsive documents.

28

DOJ’s Guide to the Freedom of

Information Act – Procedural Requirements specifies:

As a general rule, courts require agencies to undertake a search

that is ‘reasonably calculated to uncover all relevant documents.’

… the adequacy of a FOIA search is generally determined not by

the fruits of the search, but by the appropriateness of the methods

used to carry out the search.

29

Appeals filed by requesters often cite concerns with the reasonableness of an

agency’s search. Documenting the search methods used to identify and collect

documents responsive to a FOIA request provides the agency with critical

information needed to establish the reasonableness of the search.

Because the FOIA Team lacks access to all DHS systems and the knowledge

needed to run comprehensive searches within these systems, it must rely on

DHS components and OCIO to conduct searches and document the methods

used. According to the FOIA Team’s draft SOP, the FOIA Team provides a

search form to be completed and returned when it tasks DHS components and

OCIO to search for relevant records. The form sent to the components requests

information about how the search was conducted, including the locations

searched (e.g., paper files, electronic databases, desktop computers, shared

drives, and thumb drives), search terms used, time spent searching, whether

any records were found, and if the component recommends withholding

information. The form sent to OCIO specifies what key words, email accounts,

and relevant date ranges to search.

The Director of Compliance and Oversight said that, even when components

send back responsive documents, they do not always return a completed form

detailing their search methods. Additionally, OCIO sends the FOIA Team an

email stating whether it found responsive emails and the size of the data set

rather than returning the search form, which specifies key words, email

accounts, and date ranges searched. We analyzed six FOIA requests tasked to

28

Valencia-Lucena v. United States Coast Guard, FOIA/PA Records Mgmt., 180 F.3d 321, 325

(D.C. Cir. 1999) (citations omitted). See also Ancient Coin Collectors Guild v. United States Dep't

of State, 641 F.3d 504, 514 (D.C. Cir. 2011) (“An agency is required to perform more than a

perfunctory search in response to a FOIA request.”)

29

DOJ, Guide to the Freedom of Information Act – Procedural Requirements, October 12, 2018

(internal quotations and citations omitted)

www.oig.dhs.gov 11 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

DHS components, and three to OCIO. Of these nine FOIA requests, only three

(by a DHS component) returned a completed search form. In three cases, the

FOIA Team did not provide the search form when tasking the FOIA request to

the component or OCIO.

Additionally, the FOIA Team’s previous search form required the searcher to

certify he or she had conducted a reasonable search, but the current iteration

of the form does not require this certification. Since dispensing with this

requirement, neither component nor OCIO staff provide contemporaneous

certification of the reasonableness of their search.

At least half of the 60 appeal cases we reviewed challenged the adequacy of

DHS’ search. The returned search forms can be important evidence to show

DHS conducted a reasonable search. In fact, DHS has used completed search

forms and accompanying certification statements as evidence in appeals and

litigation to prove its use of appropriate methods to search for responsive

documents. Without this evidence, DHS may be placed at a disadvantage in

such litigation.

DHS Often Exceeded Its Timeliness Goal When Responding to

Congressional Requests and Redacted Information Eligible for

Release under DHS Policy

In addition to reviewing how DHS responds to FOIA requests, we sought to

determine how DHS responds to congressional requests. Unlike FOIA, DHS

does not have legal requirements dictating a particular process to follow when

responding to congressional requests; rather, DHS has developed and relies on

internal standard operating procedures (SOP) and guidance. We found DHS

exceeded its own timeliness goal for responding to congressional requests 49

percent of the time, sometimes by more than 450 business days. In some

instances when DHS exceeded its timeliness goal, it did not provide any form of

interim response. We also found DHS redacted personal information from

responses to congressional committee chairs that was eligible for release under

DHS policy.

DHS Took an Average of Almost 27 Business Days to Respond to

Congressional Requests

The DHS ESEC Executive Correspondence Handbook specifies policies and

procedures for all DHS correspondence, including correspondence with

Congress, and stresses: “In support of the Secretary’s commitment to being

responsive, the Department-wide standard is to transmit a timely response.”

www.oig.dhs.gov 12 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

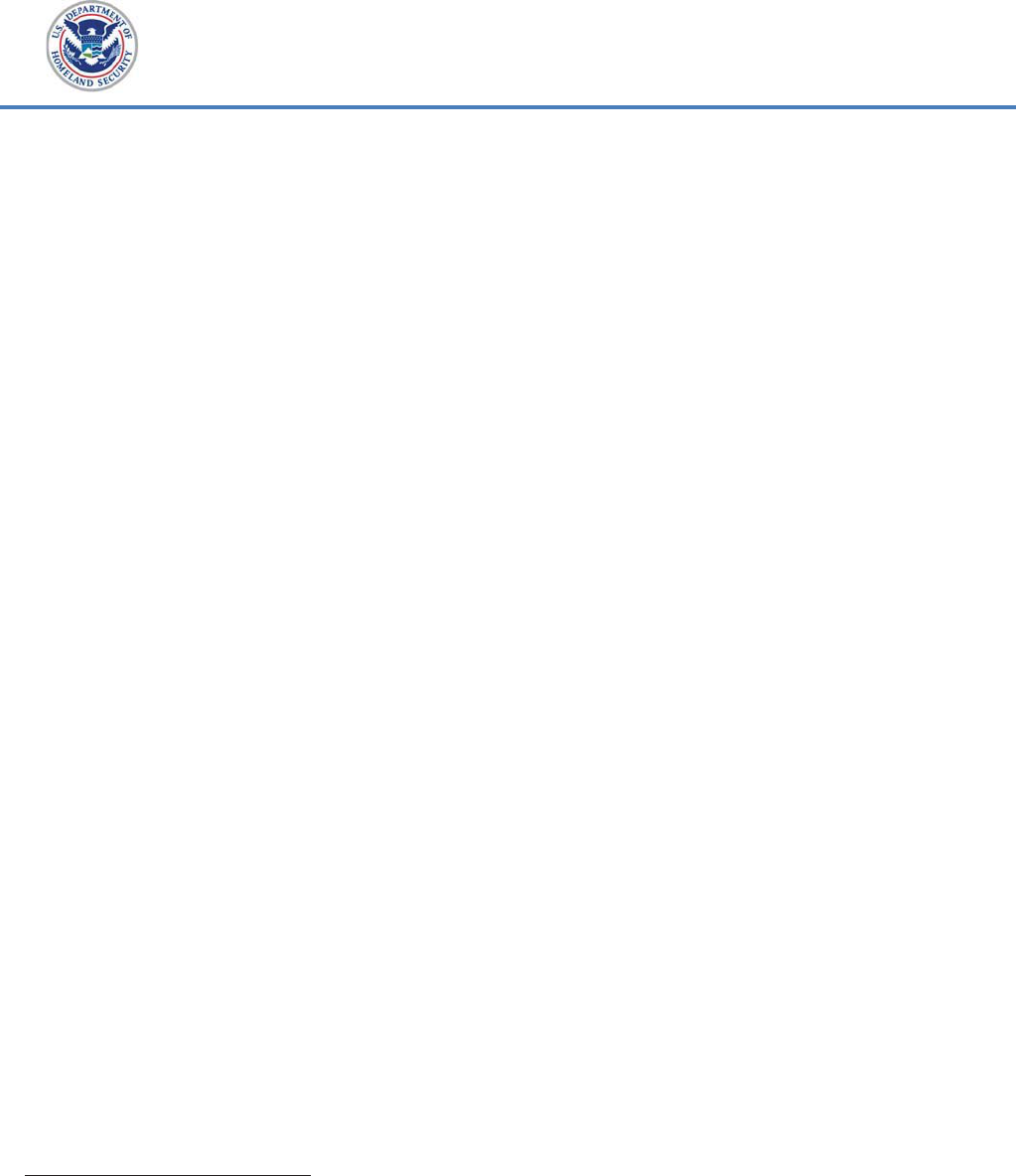

ESEC’s timeliness goal ranges from providing a response within 5 and 15

business days.

To determine whether DHS Headquarters is providing substantive responses to

congressional requests — i.e., beyond merely confirming receipt of

correspondence or providing non-substantive interim responses — consistent

with its own time goal, we analyzed data on all 2,894 congressional letters

received from October 2014 to June 2018. DHS had issued a final response to

2,832 of those letters (closed letters); 62 letters remained open. We analyzed

the closed letters and determined ESEC did not meet its response time goal of

15 or fewer business days 49 percent of the time (1,383 of 2,832 closed letters),

as shown in figure 3. On average, ESEC took almost 27 business days in that

period to close a congressional letter, with some responses going out within 1

business day, while at least one response took longer than 450 business days

to issue.

Figure 3: Timeliness of DHS Closing Congressional Letters in Business

Days, October 2014 to June 2018

51%

21%

17%

8%

2%

1%

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

1,200

1,400

1,600

15 days or

less

16 to 30

days

31 to 60

days

61 to 100

days

101 to 200

days

201 or

more days

Source: OIG analysis of ESEC data

According to the ESEC Executive Correspondence Handbook, if components

expect to exceed the timeliness goal when preparing and clearing a response to

a congressional request, components should periodically provide an interim

response. Our analysis of 30 congressional letters older than 60 business days

indicated 12 did not receive an interim letter. Seven of the 12 requests did not

receive any update — whether orally or in writing — regarding the status of the

request, meaning 7 requesters heard nothing from DHS for at least 60 days

after sending a request. ESEC staff said components do not need to provide an

www.oig.dhs.gov 13 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

interim response, but the Executive Correspondence Handbook suggests doing

so and includes an interim response template as an appendix.

ESEC and component staff told us the scope of the congressional request, the

volume of documents requested, and the review process affect how quickly they

can respond. Depending on the information requested, DHS seeks clearance

from DHS’ Office of Management, Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans, OLA,

OGC, its components, and outside agencies before release. Additionally,

requests for alien files can take longer to process because they contain

personal information and can include sensitive case information, which involve

clearance from multiple DHS components and, in some cases, DOJ.

30

For

example, DHS received a request from a congressional subcommittee for the

alien files for five individuals.

31

Roughly 3 months later, OLA informed a

subcommittee staff member the files had been reviewed by DHS, but were with

DOJ for its review. DHS ultimately provided the files, with redactions, to the

subcommittee 5 months after receiving the initial request.

DHS Redacted Information in Response to Requests from Congressional

Committee Chairs Although It Was Eligible for Release under DHS Policy

DHS may withhold or redact information requested by Congress based on a

variety of constitutional principles, common law privileges, and statutory

exemptions.

32

We did not review the legal sufficiency of DHS’ justifications in

withholding or redacting information requested by Congress, though we did

examine whether withholdings or redactions were done in accordance with

DHS’ own policies.

The OLA SOP states personally identifiable information “can be provided

following a written request from a committee or subcommittee chairman.”

Further, the ESEC Executive Correspondence Handbook, includes a call-out

text box stating,

Privacy releases are required to release an individual’s personal

information to a third party — unless the Chairperson of a

congressional committee is requesting the information in their

official capacity.

30

If an alien is under investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, then DOJ will have

to clear the file as well.

31

An alien file contains personal information on non-U.S. citizens, including name, date of

birth, place of birth, photographs, application information, affidavits, correspondence, and

more, and can be hundreds of pages.

32

Other limitations include Executive privilege, the Privacy Act, pending litigation, and

classified and sensitive materials.

www.oig.dhs.gov 14 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Despite the guidance allowing release to congressional committee chairs, we

found DHS redacted personal information in materials (e.g., personnel and

case files) responsive to requests made by committee chairs in their official

capacity. We analyzed 30 such letters older than 60 business days and found

DHS issued a response to 28 of the 30 letters.

33

Of those 28 responses, 6

included some redacted information appearing to be personal information that

was eligible for release per DHS’ guidance. DHS did not provide the basis for

withholding in any of the six responses to the committee chairpersons.

The OGC staff we interviewed stated congressional committees are not allowed

to receive “any and all” documents unredacted, and DHS redacts information

even if it is going to a chairperson. OGC staff also told us DHS does not

provide reasons for redactions in the response unless asked, stating it would

“take too long.” Further, component staff we spoke to said they never send

unredacted alien files or provide reasons for redactions. When withholding is

not required by law and disclosure is permitted under DHS’ own guidance, the

absence of explanation regarding particular redactions can create confusion

about the basis for, and legitimacy of, the redactions.

Conclusion

DHS has a responsibility to respond to FOIA and congressional requests

consistent with laws, regulations, and internal policies. Our review found DHS

struggles in the execution of that responsibility. Specifically, DHS has had

difficulty meeting FOIA production timelines and does not fully document its

FOIA search efforts, resulting in litigation risk. Similarly, DHS has struggled to

respond to congressional requests in accordance with internal timeliness goals,

meeting its response time goal slightly more than half of the time, with some

requests going unanswered for more than a year. To promote transparency

and facilitate oversight, DHS must ensure it has processes in place to respond

to these requests in a timely and efficient manner.

OIG Analysis of Management Comments

We included a copy of DHS’ management comments in their entirety in

appendix B. We also received technical comments and incorporated them in

the report where appropriate. A summary of DHS’s response and our analysis

follows.

33

We analyzed a judgmental sample (30 out of 2,896) of congressional letters.

www.oig.dhs.gov 15 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

In its response, DHS management noted that it holds a large volume of records,

including immigration records and DHS policies, which are of great interest to

the general public, the news media, and Congress. DHS management

explained that its FOIA backlog continues to be a systematic problem for DHS

but initiated its “DHS 2020 - 2023 FOIA Backlog Reduction Plan” in March

2020 to reduce the backlog. DHS management asserted that this report did

not take into account certain complicating factors that can impact DHS’

response to a congressional inquiry, including the report’s discussion of

interim responses and applying redactions.

We appreciate the efforts DHS made in providing their technical comments.

We modified the report accordingly where appropriate. Specifically, we updated

flowcharts and made minor revisions to the report to enhance clarity and

ensure accuracy. We commend DHS for proactively creating its FOIA backlog

reduction plan in March 2020 to address an issue we identified in the report.

We also appreciate DHS’ comments regarding its responses to congressional

inquiries and acknowledge DHS’ assertion that complicated factors are involved

in providing responses to congressional requests. However, as outlined in

appendix A, OIG gathered the information it relied upon for this report through

interviews with key personnel, DHS policies and procedures provided by the

DHS offices subject to this review, and a review of the underlying data for FOIA

and congressional responses. OIG attests to the accuracy of this report in

conformity with the values of the independence of this office.

www.oig.dhs.gov 16 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix A

Objective, Scope, and Methodology

Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General was established

by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Public Law 107ï296) by amendment to

the Inspector General Act of 1978.

We conducted this inspection in response to a congressional request from the

Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, Permanent

Subcommittee on Investigations to determine how DHS Headquarters is

responding (1) to FOIA requests and (2) to congressional requests.

To determine whether the FOIA Team within DHS Headquarters is complying

with Federal requirements when responding to FOIA requests, we obtained an

extract of all FOIA requests from October 2014 to May 2018. Of these, we

obtained samples of (1) search forms used for initial FOIA requests and

analyzed the completeness of the forms; (2) FOIA cases that were subject to

appeal and analyzed the adequacy of the response; and (3) all FOIA litigated

cases to determine the reasons for litigation. We also analyzed data available

on FOIA.gov. Further, we reviewed DHS and component policies and

procedures for responding to FOIA requests.

We interviewed personnel from the FOIA Team, including the Deputy Chief

FOIA Officer, directors, and processors on the FOIA Team. We interviewed

component FOIA directors from the United States Secret Service, U.S. Customs

and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the

Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Transportation Security

Administration, and the Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. We also

interviewed the Data Acquisition Manager at OCIO responsible for searching for

responsive emails.

To determine whether ESEC is responding to congressional requests we

obtained a sample of all congressional letters from October 2014 to May 2018.

We analyzed what was requested, how long it took DHS to respond, if DHS

provided an interim response, and what responsive documents DHS provided.

Further, we reviewed DHS and component policies and procedures for

responding to congressional requests.

We interviewed DHS Headquarters and component staff responsible for

overseeing and responding to congressional requests. Specifically, we

interviewed personnel at DHS ESEC, OLA, and OGC. We also interviewed

component personnel responsible for responding to congressional requests at

www.oig.dhs.gov 17 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Customs and Border

Protection, and the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

We conducted fieldwork for this review between May and November 2018

pursuant to the authority of the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended.

This report was prepared according to the Quality Standards for Federal Offices

of Inspector General issued by the Council of the Inspectors General on

Integrity and Efficiency.

www.oig.dhs.gov 18 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix C

Information Exempt from Disclosure under FOIA

Exemption

Number

Matters that are exempt from FOIA

(1) (A) Specifically authorized under criteria established by an Executive

Order to be kept secret in the interest of national defense or foreign

policy and (B) are in fact properly classified pursuant to the Executive

Order.

(2) Related solely to the internal personnel rules and practices of an agency.

(3) Specifically exempted from disclosure by statute (other than section

552b of this title), provided that such statute:

(A) requires that matters be withheld from the public in such a manner

as to leave no discretion on the issue, or

(B) establishes particular criteria for withholding or refers to particular

types of matters to be withheld, and

(C) if enacted after October 28, 2009, specifically refers to section

552(b)(3) of Title 5, United States Code.

(4) Trade secrets and commercial or financial information obtained from a

person and privileged or confidential.

(5) Interagency or intra-agency memorandums or letters that would not be

available by law to a party other than an agency in litigation with the

agency.

(6) Personnel and medical files and similar files the disclosure of which

would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.

(7) Records or information compiled for law enforcement purposes, but only

to the extent that the production of such law enforcement records or

information:

(A) could reasonably be expected to interfere with enforcement proceedings;

(B) would deprive a person of a right to a fair trial or impartial adjudication;

(C) could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of

personal privacy;

(D) could reasonably be expected to disclose the identity of a confidential

source, including a state, local, or foreign agency or authority or any

private institution which furnished information on a confidential basis,

and, in the case of a record or information compiled by a criminal law

enforcement authority in the course of a criminal investigation or by an

agency conducting a lawful national security intelligence investigation,

information furnished by confidential source;

(E) would disclose techniques and procedures for law enforcement

investigations or prosecutions, or would disclose guidelines for law

enforcement investigations or prosecutions if such disclosure could

reasonably be expected to risk circumvention of the law; or

(F) could reasonably be expected to endanger the life or physical safety of an

individual.

(8) Contained in or related to examination, operating, or condition of reports

prepared by, on behalf of, or for the use of an agency responsible for the

regulation of supervision of financial institutions.

(9) Geological and geophysical information and data, including maps,

concerning wells.

Source: 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(1) through (b)(9)

www.oig.dhs.gov 23 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

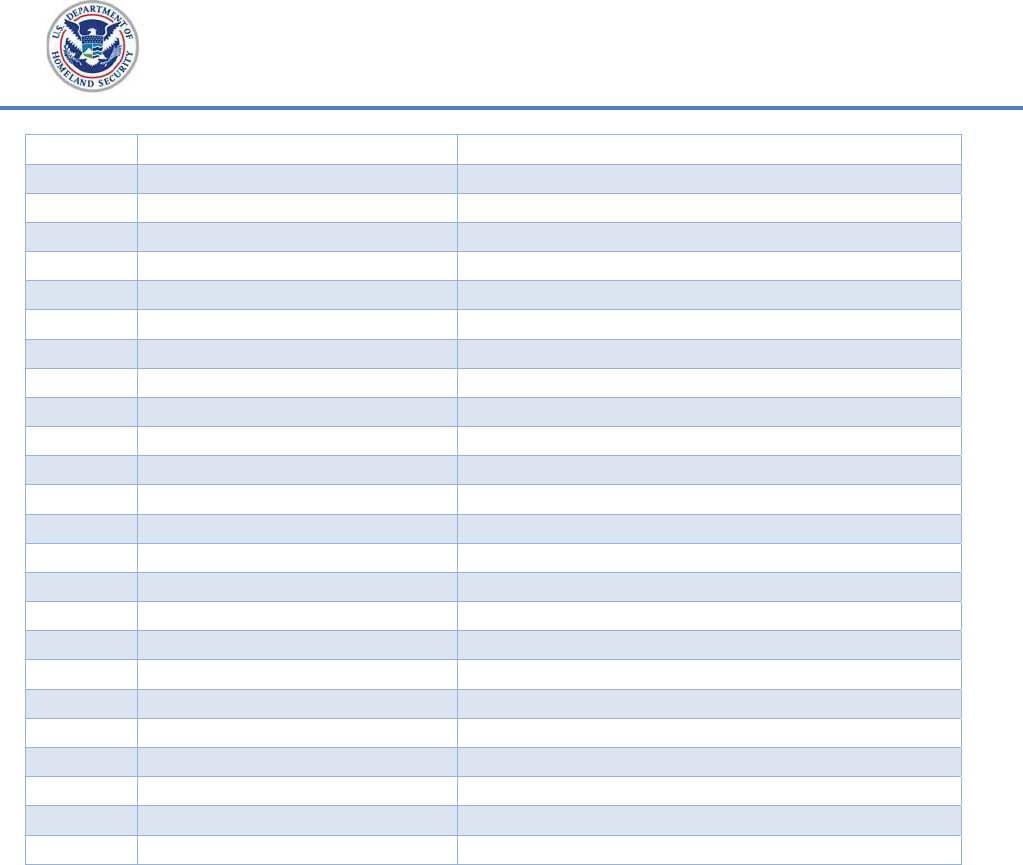

Appendix E

FOIA Litigated Cases

Cases Elapsed Business Days* Reason for Litigation

1 9 Failure to approve expedited processing

2 23 Timeliness

3 23 Timeliness

4 25 Timeliness

5 32 Timeliness

6 40 Timeliness

7 40 Inadequate Search

8 41 Timeliness

9 41 Timeliness

10 41 Timeliness

11 42 Timeliness

12 42 Timeliness

13 42 Timeliness

14 43 Timeliness

15 48 Timeliness

16 49 Timeliness

17 53 Timeliness

18 54 Inadequate Search

19 57 Timeliness

20 57 Timeliness

21 63 Timeliness

22 64 Timeliness

23 65 Timeliness

24 67 Timeliness

25 71 Timeliness

26 75 Inadequate Search

27 78 Timeliness

28 79 Timeliness

29 79 Timeliness

30 79 Timeliness

31 81 Timeliness

32 86 Timeliness

33 89 Timeliness

34 90 Timeliness

35 102 Inadequate Search

36 117 Timeliness; Inadequate Search

37 130 Timeliness

www.oig.dhs.gov 26 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

38 131 Timeliness

39 133 Timeliness

40 140 Timeliness

41 158 Timeliness

42 161 Timeliness

43 182 Timeliness

44 185 Timeliness

45 187 Exemptions

46 189 Timeliness

47 195 Timeliness

48 196 Timeliness

49 209 Timeliness

50 220 Inadequate Search

51 233 Exemptions

52 252 Timeliness

53 256 Timeliness

54 276 Timeliness

55 281 Exemptions

56 285 Timeliness

57 312 Exemptions

58 373 Timeliness

59 383 Timeliness

60 414 Timeliness

61 441 Inadequate Search

62 478 Timeliness; Exemptions

Source: OIG analysis of FOIA Team data

*We calculated elapsed business days based on the date the requester submitted the FOIA

request and the date the litigation was filed.

www.oig.dhs.gov 27 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix F

Office of Special Reviews and Evaluations Major Contributors

to This Report

Tatyana Martell, Chief Inspector

Carie Mellies, Lead Inspector

Ian Stumpf, Inspector

Avery Roselle, Attorney Advisor

Paul Lewandowski, Independent Referencer

www.oig.dhs.gov 28 OIG-20-56

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix G

Report Distribution

Department of Homeland Security

Secretary

Deputy Secretary

Chief of Staff

Deputy Chiefs of Staff

General Counsel

Executive Secretary

Director, GAO/OIG Liaison Office

Assistant Secretary for Office for Strategy, Policy, and Plans

Assistant Secretary for Office of Public Affairs

Assistant Secretary for Office of Legislative Affairs

Privacy Office Liaison

Office of Management and Budget

Chief, Homeland Security Branch

DHS OIG Budget Examiner

Congress

Congressional Oversight and Appropriations Committees

Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee Permanent

Subcommittee on Investigations

www.oig.dhs.gov 29 OIG-20-56

Additional Information and Copies

To view this and any of our other reports, please visit our website at:

www.oig.dhs.gov.

For further information or questions, please contact Office of Inspector General

Public Affairs at: [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter at: @dhsoig.

OIG Hotline

To report fraud, waste, or abuse, visit our website at www.oig.dhs.gov and click

on the red "Hotline" tab. If you cannot access our website, call our hotline at

(800) 323-8603, fax our hotline at (202) 254-4297, or write to us at:

Department of Homeland Security

Office of Inspector General, Mail Stop 0305

Attention: Hotline

245 Murray Drive, SW

Washington, DC 20528-0305