Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in

Electronic Health Records

Including Case Studies

November 7, 2013

In support of the PCORI National Workshop to Advance the Use of PRO measures in

Electronic Health Records

Atlanta, GA. November 19-20, 2013

Contact Information:

Albert W. Wu, MD, MPH

Center for Health Services and Outcomes Research

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

624 North Broadway

Baltimore, Maryland 20105

410-955-6567

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

1

This technical report was written by

Albert W. Wu, MD, MPH

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD

Roxanne E. Jensen, PhD

Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Georgetown University, Washington, DC

Claudia Salzberg, MS

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD

Claire Snyder, PhD

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary……………………………………….…..……………………. 3

Introduction…………………………………………….……….……………………. 7

What is a Patient Reported Outcome? RO…………………………………………9

Taxonomy of PROs…………………………………….……………………………. 9

Model for use of PROs for care, quality and research………….……………...... 10

Electronic Health Records……………………………….…………………………. 14

Methods………………………………………………………………………………. 16

Case Studies……………………………..…………..……………………………… 19

Synthesizing Across the Case Studies …………………………………………… 41

Summary of Systems …………………………………………….……….………… 41

Consideration of Cases by System Features…………………………………….. 42

Major Themes…………………………………………………….………………….. 46

Moving Ahead: Standardization……………………………………………………. 50

Conceptual System Architecture…………………………………………………… 51

Unanswered Questions……………………………………………………………... 52

Key Barriers and Enabling Factors………………………………………………… 58

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………. 64

References…………………………………………………………………………… 65

Figures…………………………………………….………………………………….. 78

Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………. 81

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The goal of health care systems is to obtain optimal patient outcomes, decrease risk

and disease, and improve or maintain functioning for individual and populations.

Incorporating the patient perspective through patient reported outcome (PRO)

measures is a crucial element for clinical care, quality performance management and

clinical research. PROs are any report coming directly from patients regarding their

health condition and treatment, including symptoms, functional status and health-related

quality of life. Some PRO measures are generic and appropriate for use in a wide

range of conditions, while others focus on the specific symptoms and side effects of a

given disease, condition or treatment.

The use of PROs as outcome measures in research studies dates back to the 1980s.

Since then, PRO data collection has increasingly integrated into health care. There is

now a convergence in the evolution of PRO measurement, medical record keeping and

comparative effectiveness research into an increasingly electronic and patient-centered

space. Electronic health records (EHRs) began as an electronic version of the patient

record for hospitals and clinics, and have evolved to serve a broader purpose of giving

multiple stakeholders, including providers, managers and patients, access to a patient’s

medical information across different facilities. Systems have been developed recently

that link EHRs to the collection of PRO data. One advantage of this linkage is that data

collected for one purpose can potentially be used for multiple different tasks, including

clinical care, quality assessment and improvement, research, and public reporting. Pilot

studies, implementation efforts integrating PROs into EHRs and development of PRO

research methods have received major federal support from the National Institutes of

Health (NIH), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Patient Centered

Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

(CMS), Food and Drug Administration, and the Office of the National Coordinator for

Health Information Technology (ONC), as well as private and professional organizations.

PCORI has organized a National Workshop to Advance the Use of PRO Measures in

Electronic Health Records (EHRs), to be held on November 19-20, 2013 in Atlanta, GA.

This paper provides a landscape review of the current state of use of PRO measures in

EHRs, focusing on themes in the implementation and integrations of PROs within EHRs.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

4

We focused on PRO data collection systems that were linked to an EHR system. We

did not include efforts to measure patient satisfaction independent of patient health

status, electronic reviews of systems, family history, health behaviors or health care

utilization.

The review includes 11 case studies from the US that illustrate the range of what has

been done in diverse health care settings for clinical care, quality improvement and

research. To supplement our review, we interviewed the principle developers and users

of the systems. Many of the cases used the Epic Corporation EHR with its MyChart

tethered patient portal for PRO data collection. The systems were based at Dartmouth-

Hitchcock Medical Center, Cleveland Clinic, Group Health Cooperative, Cincinnati

Children’s Hospital, Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO), Essentia Health/Minnesota

Community Measurement, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), Duke

University Medical Center, the University of California Los Angeles Medical Center

(UCLA) and the University of Michigan Medical Center, and the University of

Washington. The systems represent a broad range of functionality, patient populations

and applications. Efforts at three health care plans (KPCO, Group Health and Essentia

Health) illustrate applications of PRO collection at the plan level for clinical care,

population based screening and quality of care evaluation. Hospital based efforts at

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, the Cleveland Clinic and Dartmouth show how the use of

PROs in specialty care can expand within a hospital. The review also includes

examples of clinic-based, disease specific PRO collection (UCLA/Michigan’s My GI

Health, University of Washington Center for AIDS Research Networks of Clinical

Systems (CNICS), Duke’s Patient Care Monitor for cancer, and UPMC for primary care),

some of which show how efforts may spread to specialists outside of the originating

institution. While clinical care efforts focus primarily on providing the physician

information to use during a patient visit, some systems also elicit information for follow-

up evaluations. Essentia, through Minnesota Community Measurement, reports their

scores as part of a statewide public reporting effort. A few organizations have

integrated their systems into clinical and comparative effectiveness research

(UCLA/Michigan, Cleveland Clinic, Cincinnati Children’s, Duke), while others, like

UPMC’s system was designed to focus exclusively on clinical utility.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

5

System features were examined across the 5 following categories: system design and

implementation, measure selection, administration and data collection, reporting and

interpretation, and analysis. While some of these system features are upstream from

the technical aspects of EHR integration, each element builds the foundation for the

focus, validity, interpretation and usefulness of the PRO data available in an EHR

system. Overall the largest variations across these features were seen between

systems that were designed using EHR-based PRO collection (e.g., Epic’s MyChart

feature) and outside collection that then sought to integrate information after collection

and reporting. Systems that designed and collected PROs independently from the EHR,

presented a much different approach allowing greater freedom in PRO content selection,

more flexibility in patient access and score use, and limited ability to integrate PRO data

with other clinical care markers. These trade-offs have implications at the person-,

provider- and national-level which can be guided at this early point through

standardization, developing a broad conceptual system architecture to encourage PRO

collection compatible with larger research and evaluation efforts.

In our analysis, four major themes emerged regarding the integration and use of PROs

in EHRs: (1) Necessity of System Customization, (2) Balancing Research and Practice

Goals, (3) Demonstrating Value and (4) EHR Integration and Limitations. These

themes were important considerations for all case studies leading to key decisions

ranging from design (e.g., PRO content and selection) to intended use (e.g., clinical

care, research or quality improvement). Systems did not necessarily make similar

choices. For example the University of Washington chose to scale-up PRO collection to

implement standardized PRO collection in a national research data network

infrastructure, while Kaiser Permanente Colorado’s effort has focused on patient

screening and quality improvement. However each of these systems has considered

these themes with respect to the feasibility to sustain and expanding PRO collection

efforts into other patient populations and/or clinical settings.

There are a number of knowledge gaps identified in this report. These gaps center on

the optimal system design features for PRO collection and integration. While these

span PRO selection, administration analysis and security they all center around two

main questions: the accuracy and accessibility of PRO data in an EHR. Ultimately these

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

6

current gaps point to the necessity of multidisciplinary teams and identifying “teachable

moments” to educate clinicians, staff, researchers, and patients on PRO use.

There are a number of remaining barriers to sustainable PRO integration. These fall

under three broad categories: patient, clinician, and system functionality. The most

common barriers were related “hidden” elements linked to electronic PRO collection that

are found even in the most developed systems. Regardless of the number of system

features and staff expertise, system awareness, response rate, clinician use, and

consistent system access (e.g., enough tablets available in clinic, Wi-Fi access) all rely

on engagement from patients, clinicians, and staff. Fortunately, most barriers identified

have been shown to be somewhat modifiable, with enablers that may be scalable.

To date, the perceived benefits of using PROs in clinical care have driven the

implementation of in-clinic PRO data collection and EHR integration. Recent efforts to

support PRO collection through patient portals offer a platform to further coordinate and

develop PRO collection beyond the clinical encounter, further enhancing patient PRO

monitoring for clinic, research and QI purposes. However, other options for collecting

PROs are still necessary, including interactive voice response and in-clinic reporting.

There is a diversity of approaches to PRO integration, and coordinated efforts are

needed to increase the capacity to use them within EHRs for comparative effectiveness

research. Barriers at the level of the patient, clinician and health system seem to be

modifiable. There are considerable knowledge gaps regarding many scientific and

practical aspects of implementing PRO measures into EHRs. Funding agencies and

government bodies can support targeted research, infrastructure recommendations,

education recommendations and methods development to help overcome current

barriers, and ensure PROs can support the delivery high quality, patient centered care.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

7

INTRODUCTION

The goal of health care systems is to obtain optimal patient health outcomes, decrease

risk and disease, and improve or maintain functioning for individual people and

populations, by efficiently delivering services of the highest quality – that is, services

that are safe, timely, equitable, effective, efficient and patient centered (IOM 2001).

Health care systems should learn from experience, by collecting and converting data

about care and outcomes into knowledge. And such knowledge should be implemented

into evidence-based clinical practice, driving improvements and the process of

discovery as a natural outgrowth of patient care (IOM 2012). Health care choices made

in collaboration between individual patients and their providers are central to this

process. Incorporating the patient voice and perspective through patient reported

outcomes (PRO) measures is critical for clinical care, quality performance management,

and clinical research.

In recent years there has been a convergence of trends in the measurement of health,

the evolution of medical records, and the development of comparative effectiveness

research (Wu 2013). Figure 1 depicts the evolution and convergence these trends. The

vertical axis indicates increasing patient-centeredness, and the horizontal axis indicates

increased digitization. As the measurement of health outcomes has come to more

consistently include the patient’s own assessment of his or her overall health and well-

being, the science of PRO assessment has advanced, and the electronic collection and

storage of health data has become routine. Paper-based medical records have been

converted into electronic health records (EHRs), which can include customizable, built-

in or “tethered” patient portals. Comparative effectiveness research has become more

patient centered, with increased emphasis on stakeholder participation and capturing

the patient perspective on treatments and outcomes. Consequently, PROs, EHRs, and

comparative effectiveness research have converged in an increasingly patient-centered

and digital space, providing the opportunity for the routine implementation of clinical

systems to collection patient-reported information.

PRO data collection is increasingly being integrated into health care. In the US, the

National Institutes of Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Patient

Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) have supported the development of

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

8

PRO methods for use in research and clinical practice (Lauer 2010, Wu 2010, Selby

2012). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers, as well as

the Food and Drug Administration, use PROs to evaluate interventions and

programs(FDA 2009). The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information

Technology (ONC) has supported the use of PROs by allowing their use as evidence

that providers are making “meaningful use” of EHRs to improve quality of care or patient

centeredness, and are therefore eligible for incentive payments (What is Meaningful

Use 2013). In 2012, the National Quality Forum, the American Medical Association-

convened Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI) and the

American Society for Clinical Oncology all began initiatives to support the use of PRO

measures for quality measurement and improvement (NQF 2012a,b; personal

communication, email from Kristen McNiff, October 24, 2013). In September 2013, the

Institute of Medicine formed a Committee for Social & Behavioral Domains in Electronic

Health Records (The National Academies 2013) chaired by the Director of the NIH

Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research and PRO expert, Robert Kaplan.

PCORI is organizing a National Workshop to Advance the Use of PRO measures in

Electronic Health Records to be held on November 19-20, 2013 in Atlanta, Georgia. The

workshop aims to review the current state of use of PROs in EHRs, identify barriers and

facilitators to incorporating PRO measures in EHRs and identify specific actions PCORI

and other organizations can take to support and promote the expanded use of PROs in

EHRs.

In support of the meeting, this paper provides a landscape review (i.e., non-systematic

review) of the current state of use of PRO measures in EHRs. The pragmatic, rather

than comprehensive, nature of the review is necessary, as surprisingly little has been

published to date on most of the leading systems to measure PROs in EHRs. The

review includes descriptions of a broad range of initiatives currently underway across

the health care system to integrate PROs with the EHR. The 11 case studies illustrate

the feasibility of integrating PRO measurement systems in various clinical, health plan,

and population-based settings, and the utility of using PROs across clinical care, quality

improvement, and research settings. This review also discusses features of system

design and highlights key elements central to integrating PROs in EHRs on a larger,

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

9

broader scale – including barriers, enabling factors and current knowledge gaps.

What is a Patient Reported Outcome (PRO)?

With the recent emphasis on patient-centered care and research (Selby 2012; IOM

2001, 2012), there is also increasing awareness of the importance of incorporating the

patient’s perspective in quality measurement and improvement. One approach for

systematically capturing the patient’s perspective is the routine collection of patient-

reported outcomes (PROs). PROs are defined as any report coming directly from

patients about their health condition and treatment (FDA 2009) and include a range of

outcomes such as symptoms, functional status, and health-related quality-of-life

(Acquadro 2003). Some PRO measures are “generic” and appropriate for use in a wide

range of diseases, as well as healthy populations; other PRO measures focus on the

symptoms and side effects of a given disease, condition or treatment (Patrick 1989).

There is a long history of using PROs as outcome measures in research studies dating

back to the 1980s (Tarlov 1989; Katz 1987; Lohr 1987; Lohr 1989; Lohr 1992; Lipscomb

2005; Brundage 2007; Bottomley 2007) and somewhat more recently, examples and

investigations of using PROs for individual patient care (Nelson 1990; Wasson 1999;

Meyer 1994; Greenhalgh 2009; Snyder 2009a; Greenhalgh 1999; Valderas 2008;

Marshall 2006; Greenhalgh 2005; Aaronson 2011). A real advantage of PRO

assessment is that the data collected for one purpose can be used in multiple different

ways including clinical care, quality assessment, quality improvement, research and

public reporting (Wu 2013).

Taxonomy of PROs

Greenhalgh (2009) proposed a taxonomy for the different applications of PROs in

clinical practice. This taxonomy classifies whether the PRO data are used at the

individual or aggregated-level and whether the PRO data are used directly or indirectly

to inform patient care. For example, when an individual patient completes a PRO

questionnaire and that patient’s data are provided to his/her provider(s), the data can be

used at the individual level to screen for clinical problems, monitor progress over time,

or promote patient-clinician communication. If this information is aggregated across a

group of patients (e.g., at the provider or clinic level, or for a subgroup of patients) this

can be used to inform quality improvement or conduct population monitoring.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

10

Model for Use of PROs for Clinical Care, Quality Improvement and Research

Complementing the Greenhalgh taxonomy, Snyder and Wu (Snyder 2013a) have

proposed a model that describes the cycle of the use of PROs for quality assessment

and improvement (Figure 2). This model demonstrates how the different aspects of the

Greenhalgh taxonomy relate to each other, and can be used in a streamlined approach.

For both the Greenhalgh taxonomy and the Snyder & Wu model, it is possible to

implement either the full spectrum of applications, or one or more selected applications.

Thus, there are a wide range of opportunities for using PROs in quality measurement

and improvement.

For all applications, the cycle begins with assessing the PROs (Box 1). The

assessments may come from a number of sources, including clinical practice

applications, research studies and population surveys, as described in detail elsewhere

(Snyder 2013b). When PROs are used for clinical practice, they are collected from a

patient with the intention of informing his/her care and management. To date, the large

majority of integration with EHRs has been done for this purpose. When captured in

research settings, the most common use of PROs, it is usually as outcome measures in

clinical trials and observational studies and often occurs outside of EHR systems. In this

application, the primary purpose of the PROs is to describe the impact of various

diseases and/or treatments on measures of health extending beyond clinical endpoints.

Finally, PROs can be collected as part of population-based surveys that provide a

patient-centered perspective to complement other statistics (e.g., mortality rates)(Barr

2003).

In many cases, there is the potential to use these PRO data, regardless of the original

purpose for their collection, to evaluate the quality of care (Box 3). An example of this is

the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) Patient-Reported Outcome

Measures (PROMS) initiative (http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB11360). (NHS

2013). Specifically, the NHS is evaluating the quality of care for select surgical

interventions, including hip replacement, knee replacement, varicose vein procedures,

and groin hernias. Patients complete pre-procedure and post-procedure PROs, and

these data provide insight into the patient-centered value of the procedures overall. For

the period from April 2012 to March 2013, there were nearly 240,000 procedures for

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

11

which PRO surveys were to be collected. For the approximately 163,000 pre-

procedures surveys returned, there were 88,000 post-operative questionnaires returned

(NHS 2013). These surveys provide valuable insights into the impact of these surgical

procedures on patient’s functioning and well-being. For example, the proportion of

patients reporting improvements on a general health status measure (the EQ-5D Index)

ranged from 50% for groin hernia respondents to 87% for hip replacement respondents.

The gains on the disease-specific measures were even greater, with 83% of varicose

vein, 92% of knee replacement, and 95% of hip replacement patients reporting

improvement. In addition to providing overall perspectives on the impact of these

surgical procedures, there is also the opportunity to compare different hospital providers,

though this may require case-mix adjustment (Devlin 2010). While the NHS example is

one of the largest applications of PROs for quality measurement, other groups are also

using, or planning to use, PROs in this way. For example, the American Society of

Clinical Oncology is exploring the incorporation of PRO measures as quality indicators

in its Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, focusing first on some common symptoms

such as pain and nausea (personal communication, email from Kristen McNiff, October

24, 2013).

PROs may also be used for population health screening. In this application, PRO

measures may be administered for disease screening, or for health risk assessment

Nelson 2012). Disease screening programs can be used to identify untreated disease,

such as depression in clinical care (American College of Surgeons 2011) or more

broadly in the general population. Screening for health risks, for example, can be used

to engage and motivate individuals to pursue changes in health behaviors, and the self-

management of chronic conditions (Shekelle 2003). Health risk assessment can also be

effective at inspiring the uptake of prevention and health promotion activities in

employee health programs. Linking health promotion to health care visits and physician

advice can potentiate the benefits of PRO screening.

While it is possible to go directly from PRO assessment (Box 1) to quality measurement

(Box 3), an alternative approach would also use the data to improve the quality of

individual patient management, as well (Box 2). The use of PROs in clinical practice

involves having patients not only complete the questionnaires – but making an

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

12

individual patient’s assessment available to the patient’s provider(s) to inform that

patient’s care. Multiple systems have been developed for collecting PROs and using

them for clinical practice (Jensen In Press, Bennett 2012, Rose 2009, Basch 2009). For

example, at Johns Hopkins, we have developed the PatientViewpoint webtool that was

linked to the institution’s home-grown electronic medical record

(www.PatientViewpoint.org) (Snyder 2009, Snyder 2012, Hughes 2012,

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S-r4ykaUhfU). This tool enables clinicians to order

PRO questionnaires much in the same way that they order lab tests or imaging studies.

Patients receive an email when it is time to complete a questionnaire and the results are

provided to both the patient and clinician. The use of PROs in clinical practice can

improve patient-clinician communication, and can also have an effect on patient care

and outcomes (Hayward 2006, Valderas 2008, Marshall 2006, Greenhalgh 1999,

Greenhalgh 2005, Velikova 2004, Velikova 2010, Berry 2011, Santana 2010, Detmar

2002, Bliven 2001, Boyce 2013, Espallargues 2000, Gutteling 2008, Lyndon 2011,

Taenzer 2000, Takeuchi 2011) Thus, the PRO collection in itself can be an intervention

with the intention of improving individual-level patient care.

As noted above, using PRO data for individual patient care in no way precludes using

the data for quality measurement. In fact, it facilitates the process if collected in a

systematic way. It is feasible to take some or all of the individual patient’s PRO

assessments and aggregate them to summarize the patterns and quality of care

received at the clinic or health plan level (Box 3). Examples of this might be for pay-for-

performance, or for pubic report cards.

The next step in the process is to use the PRO data to inform quality improvement (Box

4). Dr. John Browne from University College – Cork has described how this process

works using the example of breast reconstruction following mastectomy (Browne 2009).

In Browne’s example, individual surgeons are presented with the average PRO scores

of their reconstruction patients. The surgeons’ performance falls into a distribution, with

some surgeons’ patients reporting lower PRO scores and other surgeons’ patients

reporting higher PRO scores, on average. While PRO measures provide some

indication of relative performance, scores alone are not particularly illuminating in terms

of how to improve care. The key is to be able to translate the scores into descriptive

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

13

labels that can inform patient management. In Browne’s example, lower scores reflect

women who find their breasts’ shape to be acceptable when clothed; the average

scores reflect women reporting that their breasts ‘line up’ when unclothed; and the

highest scores represent women who report that their breasts are equal in size and

shape when unclothed. These descriptive labels can inform a lower-performing surgeon

regarding what areas require increased attention, making the PROs a powerful tool for

quality improvement.

The cycle then begins again with PRO assessment (Box 1) – ideally, with the PRO

scores demonstrating the improvements based on the applications of the PRO data for

quality assessment and improvement (Boxes 2-4). In addition, having accumulated a

number of PRO reports creates another opportunity for using the PROs in clinical

practice (Box 2). That is, group-level PRO data can be assembled in the form of

decision aids that can be used to explain the implications of treatment alternatives and

help patients and clinicians decide on the appropriate strategy for a given patient. In

contrast to the use of an individual’s PROs informing his or her care, in this application,

PRO data from other patients are summarized and presented to a patient to help

him/her understand other patients’ experiences with the various treatment options. For

example, Brundage et al. have shown that lung cancer patients presented with the

hypothetical option of chemotherapy used information regarding the impact of

chemotherapy on survival, toxicity as well as on health-related quality of life to inform

their decision (Brundage 2005). Thus, as more data are collected about patient

experiences using PROs, more patients can benefit from a clearer understanding of the

quality-of-life implications of different treatment options. This cycle is exemplary of the

functioning of a learning health care system – one in which best practices are

embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge is captured as an integral

byproduct of the delivery experience (Olsen 2007).

While the above discussion of the applications for PROs in quality measurement and

improvement around the cycle focuses primarily on the PROs themselves, the power of

PROs increases substantially when the PRO data are linked with other clinical

information (Wu 1997, Snyder 2013b). Linkage to treatments and clinical events can

provide information about treatment effectiveness for individual patients, while linkage to

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

14

patient and disease and provider characteristics can help to generate evidence about

the effectiveness of the care delivered by providers. The integration of PROs in EHRs

offers great potential in terms of applying PROs during each phase of the cycle. Below,

we provide additional background on EHRs and then describe how PROs, combined

with the EHR data, create valuable opportunities for patient-centered care and research.

Electronic Health Records (EHRs)

A more detailed review of EHRs is beyond the scope of this paper. The following is a

brief history of the development of the electronic health record and a description of its

current state. An EHR can be defined as a systematic collection of electronic health

information in digital format about individual patients or populations. Data may be

captured in many ways, including as structured data that can be subjected to immediate

analysis and other ways such as free text or images. Information is stored so that it can

be accessed across different health care settings including hospitals, clinics and other

care facilities, and even by individual patients. EHRs can collect a broad range of data,

including patient demographics, medical and social history, medication and allergies,

diagnoses and problems, immunization status, laboratory and other test results, vital

signs, physical examination findings, billing information and various documents.

Additional functions include the ability to execute orders for tests and medications,

schedule future appointments, generate referrals to other providers, track care and

outcomes, trigger warnings and file public health reports. Information within an EHR

can be used for secondary analyses for research, quality assessment, quality

improvement and reporting (Weiner 2012).

The acronyms EHR and EMR (electronic medical record) are often used

interchangeably. An EMR denotes an electronic version of the patient record created

for hospitals and clinics whereas an EHR has a broader purpose of giving access to a

patient’s medical information to multiple stakeholders across different facilities within

and institution or network, including patients, health care providers, managers, payers,

insurers, and employers.

The modern medical record dates back to the 1970s when records were still maintained

exclusively on paper (Weed 1972). There were a few initial attempts to digitize these

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

15

records and provide computerized decision support (NIH 2006). Electronic medical

records began to be developed in the 1980s for administrative purposes. A notable

effort was the Veterans Administration’s VisTA which was adopted universally across

VA Medical Centers (Brown 2003). In the 1990s the first Windows-based medical

records were released (NIH 2006). The scope of EMRs broadened in the early 2000s to

include a range of non-clinical health information, leading to the term "electronic health

record". Some of these EHRs have integrated patient portals and allowed patients to

communicate securely with health providers and to enter additional information. The

process was greatly accelerated by passage of the Health Information Technology for

Economic and Clinical Health Act and availability of stimulus funds to reward the

“meaningful use” of data by adopters of EHR (ONC 2012). A move to develop

standalone personal health records was also initiated (Tang 2006), which is proceeding

with increasing success but will not be reviewed here.

As these systems have developed, EHR-based patient portals (referred to as tethered

portals) have emerged as the most prevalent structure. These portals permit patients to

retrieve their records and to enter additional information (Tang 2006). It is uncertain

what proportion of EHRs have the capacity to collect PROs. A number of standalone

web tools have been designed specifically to capture and report PRO measures, in part

in response to the lack of availability of this capability within existing EHRs. Most of

these do not interface directly with EHRs. Other example as mentioned above is

PatientViewpoint, developed by our group (which does link to the EHR), with other

examples of integrated systems identified in the case studies section (Snyder 2009,

Snyder 2012).

EHRs systems have the potential to enhance patient-clinician interactions through the

incorporation of patient-level PRO scores. In some EHRs, clinicians can access

reference materials to support decision-making. Other systems have automated alerts

and decision support that is built-in to help guide practice precisely when it is needed.

Today, over 57% of office-based physicians use EHRs (Hsiao 2011). Concurrently,

despite worries about a potential “digital divide” exacerbating existing disparities in care,

internet use is increasingly prevalent for both genders and all age groups,

races/ethnicities and income levels. This advance is due in part to internet access from

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

16

laptops, tablets, telephones and other handheld devices (Zickuhr 2012).

We are now in the midst of a period of rapid development of EHRs capabilities

alongside an even more rapid proliferation of web-based options for PRO collection. A

natural place for these data to go is into EHRs, but there is relatively little published on

the best practices and new developments in linking PRO data collection to the EHR. For

that reason, we undertook a search of the published and grey literature on the current

state of use of PRO measures in electronic health records. We were interested in

identifying highly developed and innovative systems for PRO data collection that feature

EHR integration. We were also interested in common themes in the implementation and

integration of PROs within the EHR, including barriers and facilitating factors, and in

identifying key unanswered questions important to the future on PRO measure

integration in the EHR.

METHODS

We conducted a landscape (non-systematic) review to identify existing and leading

systems that collect PROs and link to EHRs. We were interested in systems that were

used in clinical practice. Systems were eligible if they are used in clinical care settings,

assess PROs electronically and provide summaries of the patients’ response to

providers.

Systems were identified through publications, as well as conference abstracts, white

papers, reports published online or in print and other grey literature. The latter included

information from unpublished presentations, publications and news reports. We

obtained additional detail through interviews with key informants identified by the

Planning Committee and our own network of colleagues and collaborators. PubMed,

MEDLINE and Embase searches used the following terms: [patient-reported outcomes

(outcome assessment, quality of life, health status indicators, patient-reported), and

clinical care (patient care, clinical care, delivery of health care)]. We excluded PRO

data collection systems intended exclusively for clinical trials. We also excluded

electronic PRO data collection systems that were not linked to EHRs. This exclusion

category included some major PRO reporting efforts (Meyer 1994, Gustafson 2001,

Wasson 1999,http://www.howsyourhealth.org/, Cohen 2013), but allowed this report to

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

17

specifically focus on how PRO data is integrated with EHR information. In addition, we

did not include the large number of efforts to measure patient satisfaction independent

of PRO measures of health status. We did not include the many other different kinds of

health related information, including the review of systems, family history, health

behaviors such as tobacco or alcohol use, and health care utilization.

We limited our selection of case studies to US systems (Table 1) although there are

important international efforts of note (Gilbert 2012, Dudgeon 2012, Black 2013,

Varagunam 2013; Bainbridge 2011, Engelen 2010). The cases we present do not

represent the full range of systems. While PRO collection and integration are most

common in specific clinical populations such as cancer, rheumatology and orthopedics,

we selected systems that represent a range of applications from the general population

to specific disease conditions. We included cases used in health systems with different

payment and organizational models and different scale from small to large. For each

case study, system characteristics and clinical implementation were identified and

abstracted using a structured review form created by the authors. We supplemented

the reviews with interviews with the principal system developers and users.The

summary extract of information was verified with the system developers from whom we

also obtained follow-up information when necessary. Table 1 summarizes the 11 case

studies, including their system affiliation and name, the initial clinical population, and

whether they are used at multiple practice locations and for multiple patient populations.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

18

TABLE 1: SUMMARY OF CASE STUDIES

# System Affiliation (Name) Initial

Population

Multiple

Sites/Clinics

Multiple

Populations

1 Epic Systems Corporation

(MyChart, EpicCare)

Epic Users Y Y

3 Cleveland Clinic (Knowledge

Program)

Neurological

Disorders

Y Y

2 Dartmouth Spine Center Spine Y Y

4 Group Health Cooperative

(Health Profile e-HRA)

General Y N

5 Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Rheumatology Y Y

6 Kaiser Permanante Colorado

(PATHWAAY)

Older Adults Y N

7 Essentia Health (MN

Community Measurement)

Depression Y N

8 University of Pittsburgh Medical

Center

Primary Care Y Y

9 Duke University (Patient Care

Monitor)

Cancer Y Y

10 UCLA/Michigan (My GI-Health) GI Disorders Y N

11 University of Washington/

Centers for AIDS Research

Networks of Clinical Systems

HIV Y N

For each case, the first page provides an overview of the system and its development,

including conditions and PROs included; the nature of integration of PRO measures

within the EHR, applications in clinical practice, research and quality improvement, and

future plans for the system. The facing page shows a graphic example of one aspect of

the system, a walk-through of the process of patient assessment and data flow, key

themes highlighted by the case, and data sources.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

19

Epic Systems Corporation MyChart

Basic System Summary:

MyChart (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) is a secure member website through

which registered patients can view portions of their medical record and exchange secure

messages with physicians. Although collection of PROs within Epic had been

implemented prior to the 2012 release of MyChart, the release of the “series” feature for

PRO ordering and “definition” tool added features that added value for researchers. Epic

has been granted permission to provide the following PRO measures as part of their

Foundation System. They are:

Measure Dimensions

Medical Outcomes Study SF-20 (20 item Short Form health survey), RAND-36

PHQ2/PHQ9 Depression

PROMIS

Adult (18 years and

greater) static short forms

Physical Functioning (10 items); Pain Interference (8 items);

Global Rating of Pain (1 item); Sleep Disturbance (8 items);

Fatigue (8 items); Depression (8 items); Anxiety (8 items);

Satisfaction with Participation in Social Roles (8 items)

Pediatric Self Report (8-

17 years) static short

forms

Physical Functioning--Mobility (8 items); Pain Interference (8

items); Global Rating of Pain (1 item); Fatigue (10 items);

Depressive Symptoms (8 items); Anxiety (8 items); Peer

Relationships (8 items)

Proxy (5-17 years) static

short forms

Physical Functioning--Mobility (8 items); Pain Interference (8

items); Global Rating of Pain (1 item); Fatigue (10 items);

Depressive Symptoms (8 items); Anxiety (8 items); Peer

Relationships (8 items)

EHR Integration:

Complete integration with the Epic EHR. PRO scores can be viewed and manipulated

alongside other clinical data elements such as laboratory test results.

Clinical Practice:

Epic ‘series’ definition functionality makes it possible on an individual or sub-population

basis (e.g., all patients age >

65) to specify the timings and intervals of automated

releases of one or more PRO measures. Organizations can build additional

EpicCare/MyChart questionnaires

Research-Related:

It is possible to specify the timing and intervals of automated releases of PRO

assessments. PRO data are aggregated across patients in Epic’s analytic environments

(Cogito Clarity and Cogito Data Warehouse) with common data structures across

organizations.

Quality Improvement:

Organizations that have implemented Clarity and/or the data warehouse are able to

develop reports that include PRO data.

Future Plans:

Long-term plans are to expand to additional PROs in their Foundation system.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

20

Epic Systems Corporation: EpicCare longitudinal integration of PRO and clinical

data

Walk-through of the Patient Assessment Process

A provider working within the EpicCare EHR orders one or more PROs to be completed

by the patient. The patient receives secure email notification via the MyChart patient portal

and completes the PRO assessment online. The results are released immediately to the

EpicCare EHR where they can be viewed by the provider alongside other test results.

Key Themes

• Completed via tethered patient portal MyChart

• Fully integrated within Epic ecosystem including EpicCare EHR. PRO data are

aggregated across patients in Epic’s analytic environments (Cogito Clarity and

Cogito Data Warehouse)

• Foundation system includes pre-specified PRO measures

• New PRO measures require Epic trained programmers to implement within

MyChart

Sources: Unpublished presentations, discussion and email communication (Nancy

Smider)

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

21

Cleveland Clinic Knowledge Program

Basic System Summary

The Knowledge Program (KP) is a data collection system and repository designed to

enhance electronic clinical data, including the addition of PROs. Goals were to help guide

care, to link to CarePaths (CP) to standardize management of specific conditions and to

increase the ability to extract data from the EHR for secondary use. KP was developed in

2007 by the Neurological Institute (NI) of the Cleveland Clinic in collaboration with the

Imaging Institute and IT Division. All departments in the institute started simultaneously in

a “Big Bang.” KP uses both standard PRO measures and custom questionnaires, which

can be built quickly using a content manager tool. Conditional flows of questions can be

built in. There are provider questions to create metadata, e.g., why the patient did not

complete a PRO or date of a clinical event. A KP query tool can extract different kinds of

data for secondary use. Most patients surveyed thought the data were useful (especially if

the provider reviewed results with the patient) and questionnaires were not too long.

Completion rates are >80%. The majority of providers surveyed also reported that PRO

data were useful. KP now includes all of orthopedic spine surgery, cardiology,

gastroenterology, head & neck, and plastic surgery. In addition to the standard EQ-5D and

PHQ-9, KP also collects the PDQ, a Pain scale, Central Sensitization Inventory, Modified

JOA (neck or cervical myelopathy) and questions on days missed and work status, for a

total of 164 PROs or ClinROs.

EHR Integration

: Survey build and data collection are done outside of the Epic

environment, but reports are viewable in EpicCare. Office-based collection of data via

tablets goes to a custom “NI health status” tab in the Epic navigation panel. The provider

display comprises screen shots, flow sheets and text and cannot be manipulated within

Epic. NI has encouraged use of MyChart for PRO data collection prior to an ambulatory

visit – MyChart now comprises up to 23% of PROs completed.

Clinical Practice

: A total of over 961,000 patient visits to 1,062 providers; There are more

than 330,000 individual patients with PRO data since 2007. Scores can be tracked over

time within KP. Neurologists have found PHQ9 helpful. A best practice alert (BPA) was set

for a score greater than 15; an order set pops up with recommendations for

antidepressants, referral to behavioral health specialists, and patient education.

Research

: In neurology, PROs are used in clinical research to track response by disease

and type of patient, and how depression affects management and outcomes for specific

conditions. Ortho/spine finds KP to be very useful, with 3-4 of their faculty doing

exclusively outcomes research. There are some frustrations with missing data and follow-

up. Many current studies are ongoing including: CER, e.g., in degenerative

spondylolithesis, radiculopathy treatment; Methodologic: e.g., responsiveness of mJOA

score to improved QOL; Clinical, e.g., the effect of obesity on patient outcomes; Health

services research: cost of surgery vs outcome; outcomes for 8 different surgeons (Gross

2013; Gogawala 2011, Conway 2012; Su 2012, Jehi 2011).

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

22

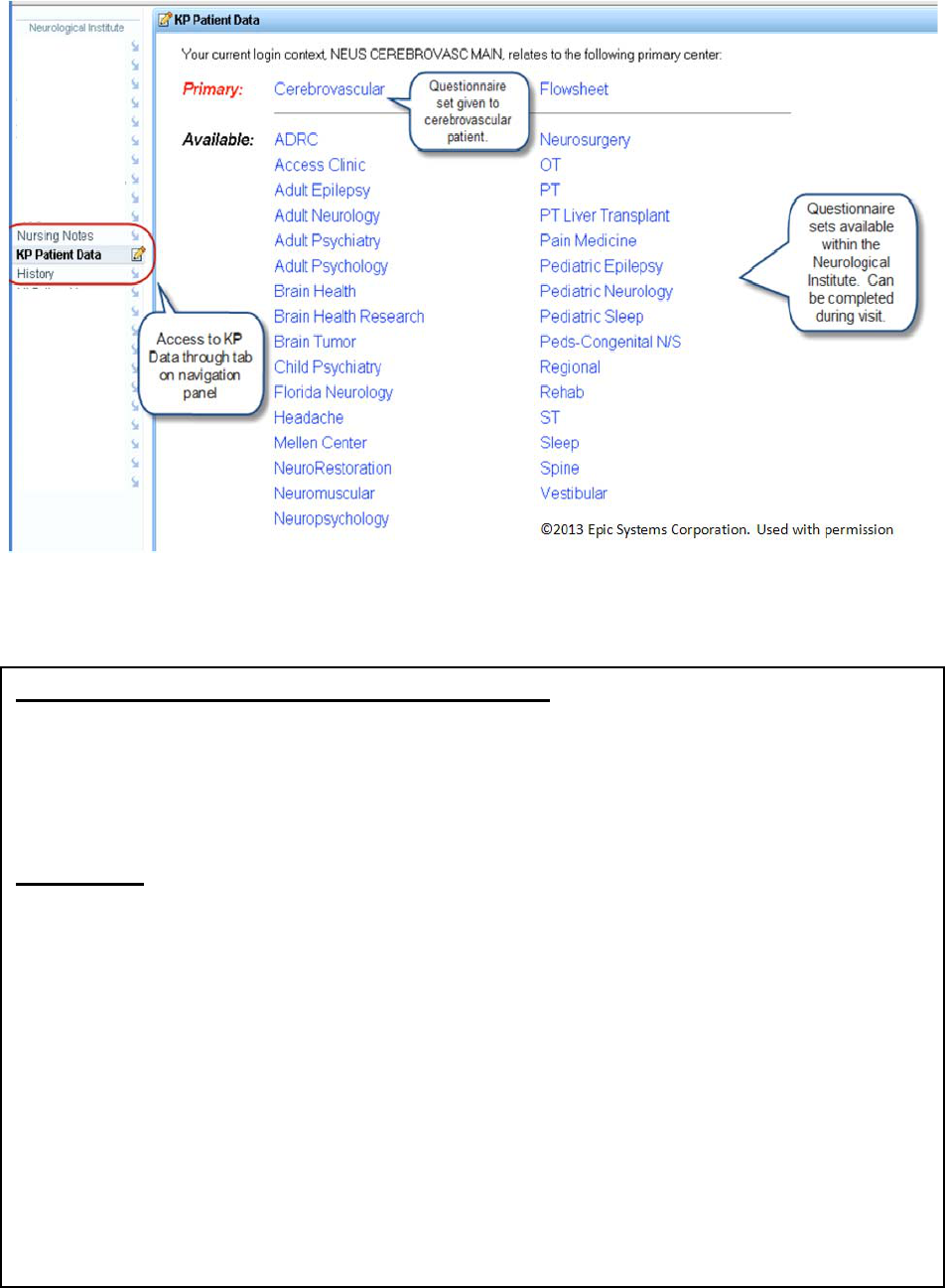

Cleveland Clinic Knowledge Program: PRO measure sets available in EpicCare

Walk-through of the Patient Assessment Process

Data collection is currently mostly on tablets which are given to patients in the office

waiting room when they arrive to register. Kiosks and increasingly MyChart (over 20% of

all PROs completed in 2012) are also used for data capture. The data go into the KP

databases and can also be seen by providers on a “KP Patient Data” tab in the Epic

navigation panel. A KP tool allows data extraction for research and quality improvement.

Key themes

• Initially built around neurological disease. Goals included individual patient care,

quality of care, research and policy/reimbursement (demonstrating outcomes

needed to show value)

• Large number of standard and custom PROs (and some ClinROs: a total of 164

patient or provider questionnaires)

• Initially tablet computer entry, now increased proportion via MyChart with

integration with EpicCare EHR

• Important enablers: leadership support, effort was clinically driven, allowing

individualized questionnaires, availability of metrics on completion and use,

integration of technical and clinical teams

• Barriers: dedicated resources are needed to analyze and report PRO results

Sources: KP webinar August 7, 2013; discussion (Irene Katzan, Ajit Krishnaney, Eric

Mayer); Katzan 2011 a,b; Katzan 2012; Atreja 2012; Gurland 2010).

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

23

Dartmouth Spine Center

Basic System Summary:

The Dartmouth system is a PRO data collection system integrated within the Epic EHR.

The Center began PRO data collection efforts in 1998, based at the Dartmouth Hitchcock

Medical Center in Lebanon, NH, led by Dr. James Weinstein (Weinstein 2000). The

collection of structured PRO data before each visit was a fundamental process for the

achievement of care planning, shared decision making, monitoring individual impact of

treatment and quality improvement, research, and public reporting. In 2005 Dartmouth

partnered with Dynamic Clinical Systems to collect PRO measures, interfacing with their

home grown EMR. At the time, reports were visible in the EMR as blocks of text. The initial

driving force came in part from early adopters who already believed in the value of PROs.

Every condition had a local physician champion and selection of PROs came about from

extended conversations among a multidisciplinary team. In April 2011, Dartmouth

transitioned to Epic and the decision was made to do as much as possible within Epic to

minimize interfaces. Dartmouth is currently collecting PROs within 12+ clinical programs

(Ortho, Plastics, Spine, Pain, Heme/Onc, Psychiatry, OB/GYN, Rehab, Neurology, Primary

Care, Surgery/Anesthesia, Vascular) and 25+ different health conditions

(Hip/Knee/Shoulder; Hand/Breast; Breast, Head & Neck, Neuro and Prostate Cancer;

Sleep, Depression, Anxiety; Epilepsy/MS). PRO measures include PROMIS, VR 12, PHQ-

9, condition specific instruments, a risk assessment tool, alcohol screening, and many

custom questionnaires (e.g. Review of Systems, ADLs). Baseline collection rate is >80%

but is more limited for follow-up data.

EHR Integration:

Data collection is either via MyChart or Welcome tablets/kiosks in the office and is fully

integrated in EpicCare EMR. Foundation PRO measures are entered as discrete data and

can be manipulated in Epic. The care team can review results immediately in chart review

or visit navigator.

Clinical Practice:

All electronic communication is via a secure patient portal. Summary reports are generated

from PRO data for making and monitoring the care plan. A survey of spine patients

(Hvitfeldt 2009) found that 80% rated the system excellent to good and 1/3 reported that

PROs had led to positive changes in their visit (pre EPIC implementation). Clinicians

reported that PRO measurement systems were important for follow up and feedback but

expressed mixed views on whether it saved or added time to the visit. Alerts are set up for

patient reports of suicidal ideation.

Research-Related:

PROs are used in practice-based research. Research consent forms are programmed like

other questions into the system. The Spine Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) has

followed thousands of patients in 13 centers for >5 years, with most of the primary results

based on PRO data (Weinstein 2006, 2007).

Quality Improvement:

Data are used for program performance and improvement, and are reported on the

Dartmouth public website.

Future Plans:

Long-term goals are to improve the ability of clinicians to order PROs, to increase the

customization of clinical reports, and to improve score interpretation for patients and

clinicians. Additional goals are to improve compliance with follow-up PRO data collection

and system capabilities to extract population data for quality improvement and research.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

24

Dartmouth Spine Center: PRO domains flowsheet data in EpicCare

©2013EpicSystemsCorporation.

Usedwithpermission

Walk-through of the Patient Assessment Process

When a new patient or an annual visit is scheduled the scheduling system follows rules to

order appropriate PRO measures that are tied to the upcoming appointment. If the patient

is active on MyChart, s/he gets appointment and questionnaire reminders. If not, or if the

patient does not fill out the questionnaire through MyChart, the patient receives a tablet at

check in and completes PROs in the waiting or exam room. When the patient sees the

clinician they review current and trended data. The clinician charts core/meta data on the

patient. The warehouse receives, stores, manages, and analyzes data from multiple

sources including diagnostic tests and claims. The warehouse distributes reports for

individual patients, clinical populations, quality measures, and research. The next release

of Epic will allow series of PROs to be ordered.

Key themes

• Initially built for spine surgery, vision was importance of the patient perspective,

collecting information at point of care, simultaneously built into research.

• PROs for 12 different clinical programs and 25 different health conditions.

• Initially based on Dynamic Clinical Systems for PRO data collection and home

grown EMR, switched in 2011 to Epic and MyChart with some losses and gains in

functionality.

• Important enablers: support from top clinicians and leaders and enthusiasts; effort

was clinically driven

• Barriers: Epic lacks easily accessible features to customize clinical reports. It has

taken significant resources and expertise to get a standard report on questionnaire

completion rates.

Sources: KP webinar October 30

,

2013

;

discussion

(

Carol

y

n Kerri

g

an

)

;

Nelson 2012

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

25

Group Health Cooperative Health Profile (Health Risk Assessment)

Basic System Summary

The Health Profile is an electronic Health Risk Assessment (e-HRA) that targets adults and

is integrated with the EpicCare electronic record at Group Health Cooperative, a large

health plan in Washington State. The overall goal is to provide advice to patients and their

providers based on information entered by patients via the patient portal (MyGroupHealth)

that is integrate in the EHR. In 2006, Group Health developed the interactive online e-HRA

that collects information from members, integrates it with other EHR data and produces

individualized health improvement recommendations. The recommendations align with

Group Health’s clinical practice guidelines. The goal is to promote prevention and health

promotion behaviors through patient interaction with their Health Profile. Preventive health

behaviors are reinforced by clinicians since the recommendations align with Group Health

clinical practice guidelines. Data are also used for quality improvement. PRO measures

are part the e-HRA, including functional health status, health-related quality of life, and the

PHQ-2. The questionnaire takes approximately 20 minutes to complete and incorporates

branching logic and algorithms. Health Profile data appear in EpicCare as structured data,

free text and reports. Past reports are archived and can be reviewed. Messages are

triggered if an urgent need is identified. There is a paper-based alternative that is not

linked to the EHR.

EHR Integration:

Data collected via MyGroupHealth flow as reports into EpicCare. There is 70% uptake of

MyGroupHealth. These are structured data elements that cannot be manipulated within

Epic. Data are summarized in recommendations to be reviewed by the patient and

clinicians.

Clinical Practice:

Design of the system was driven largely by clinicians and executed by an integrated

multidisciplinary team. Selection of instruments, risk calculation and recommendations are

evidence based so they are more likely to be taken up.

Research- Related:

There has been relatively little use for research thus far.

Quality Improvement:

Population-based estimates of disease risk, health status, and gaps in care are delivered

to health care purchasers and to Group Health managers to direct resource allocation,

care management programs, and quality improvement activities.

Future Plans:

Long-term plans are to improve integration of reports and data within EHR. No specific

plans for expansion.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

26

Group Health: Health Risk Assessment viewed in EpicCare

Walk-through of the Patient Assessment Process

A new member is made aware of the HRA when s/he logs on to MyGroupHealth or

alternatively, from a prompt from an employer that provides an incentive for completing it. If

members do not complete it within 1 year, they receive a prompt. When the member

completes the HRA (takes approximately 20 minutes) s/he is provided with immediate

personalized health recommendations. A similar report goes immediately into EpicCare

and is available for clinicians to review. Specific patient risk factors trigger

recommendations based on Group Health clinical practice guidelines. Data are stored in

Epic and in a database for analysis and aggregation.

Key themes

• Part of a comprehensive e-Health Risk Assessment

• There is 70% uptake of MyGroupHealth patient portal

• PRO data and other patient output from the HP are viewable as PDFs in the EHR

• Important enablers: Employer incentives to complete the e-HRA

• Barriers: Full integration with the EHR is costly and complex and not yet

accomplished.

Sources: GHC internal documents; discussion (Paul Lozano, Rob Reid) (Reid 2010,

Nelson 2012)

©2013EpicSystemsCorporation.

Usedwithpermission

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

27

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Basic System Summary

The Cincinnati Children’s system uses a tablet- and kiosk-based PRO data collection

system that integrates via Welcome with the Epic EHR. Cincinnati Children’s started

collecting PROs for clinical use five years ago under a broad strategic initiative to improve

patient outcomes with a focus on quality improvement methods and tracking of

performance and outcomes metrics. Individual clinics were invited to identify 3 medical

conditions on which to focus for their panel of patients. Efforts to collect PROs at the

hospital level have ramped up over the past two years, with a focus on using the best

possible methods and evidence possible with a trained psychometrician hired full-time to

consult with clinics on measure selection and data analysis. Currently, a number of clinics

are collecting a widely used PRO, the PedsQL™. The completion rate of patients eligible

to receive the measure via tablet is 79%. Many of the disease-specific and functional

measures developed and used at the clinic level are administered to targeted patient

groups.

EHR Integration:

Patients are administered questionnaires at intake based on provider-specified variables

pulled automatically from their EHR and date of previous survey (if previously

administered).

Clinical Practice

PRO scores generated using an algorithm within Welcome are used at the point of care to

inform the visit. In the rheumatology clinic physical function and pain interference are

important patient outcomes that are tracked and reviewed at each visit. Changes in these

scores are used to help identify and select the appropriate patient intervention (e.g.,

medication adjustment, physical therapy). In the Heart Institute, children with

cardiomyopathy are provided a depression PRO. Depression has been found to impact

clinical results in children with chronic diseases therefore the goal is prompt identification

and intervention. The Food Allergy clinic is working to identify anxiety children experience

from their allergic state. The goal is again prompt identification and intervention.

Research- Related

All administered measures must have a clinical rationale; nothing is collected purely for

research purposes. Examples of research are: Evaluation of psychometric properties of a

short version of the Children’s Depression Inventory in a clinical setting, and for Type 1

Diabetes care.

Quality Improvement

Key goals of quality improvement efforts are to reduce staff involvement in PRO

administration and minimize patient burden. Many different quality improvement methods

(e.g., swim-lane diagrams, process flow maps, PDSA cycles) have been applied at the

clinic-level to streamline the integration of PROs into the clinic work flow and capitalize on

electronic system automation to reduce staff burden. Results of these efforts include

identifying patients that receive a large number of pre-visit PRO questionnaires (e.g.,

psychological batteries) and scheduling those patients to come in 20 minutes earlier.

Future Plans

Long-term goals are to create a clinical repository for CER, and integrate dynamic

assessment (e.g., PROMIS CATs). Eventually, would also like to push all PRO and other

patient information capture outside of the patient visit.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

28

Cincinnati Children’s: Child PRO assessment (Used with permission)

Walk-through of the Patient Assessment Process

At the registration desk, the patient is given a personal numeric code and either a portable

electronic tablet or directed towards a computerized kiosk. The code is linked to their

electronic medical record ID. A pre-programmed algorithm (based on diagnosis, age, time

interval since previous assessment, and previous PRO scores) selects PRO

questionnaires personalized for the patient. If PRO questionnaires are not completed in

the waiting room, the tablet can be taken with the patient to the exam room. Clinicians

review scores with patients during the clinic visit.

Key Themes

• Automatic PRO selection is driven by patient characteristics

• Strong institutional support and infrastructure

• Focus on automation and workflow integration using quality improvement methods

Sources: Discussion (Esi Morgan-DeWitt, Ian Kudel, Evi Alessandrini)

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

29

Kaiser Permanante Colorado (KPCO) Proactive Assessment of Total Health &

Wellness to Add Active Years (PATHWAAY) for Seniors

Basic System Summary

The KPCO program is a comprehensive, population based method of screening to deliver

evidence-based interventions for common geriatric issues, developed in 2011. PROs are

seen as essential to handling geriatric problems. The goal was to develop a system of

member health assessments including PRO that links to the EMR (Epic) and integrates

with care to produce individualized action plans. Additional goals were to extract data from

the EHR for quality measurement and research. Interactive voice response (IVR) was

developed to allow data collection for patients not using KP.org (aka MyChart). IVR data

are also integrated into the KP Health Connect (aka EpicCare) EHR. Pilot work was

conducted in 2012 at 2 clinics, with implementation by July 2012 in all 24 KPCO primary

care clinics. PROs collected are part of the Total Health Assessment questionnaire,

including PHQ-2 and pain. Among seniors who rated the online process, 72% rated it “very

easy” to use. This rating increased to 75% for the IVR process. Patients are given

Personalized Prevention Plans (PPP) which are also integrated into Epic. People with

positive triggers get direct telephone outreach. Use of automation and centralized support

($700K in salary+benefits) is estimated to save 3.2 FTE of added PCP time resulting in

>$200K net savings.

EHR Integration: Both data collected via KP.org, and IVR data flow directly into KP Health

Connect EHR. Actual data elements can be manipulated within Epic. Data are summarized

in Health Trac, a PPP letter is created in Health Connect and is ready to be reviewed by

the clinician. SmartSets are available to order subsequent testing and treatment. Data can

then be extracted from the Epic Clarity database

Clinical Practice Since July 2012 over 41,000 of a total population of ~90,000

seniors have completed an annual wellness visit, of whom 78% completed a THA, 72% of

them before the primary care visit (40% via KP.org). Within Health Connect, screening is

followed by evidence-based interventions for the related geriatric issues. For example, a

positive screen for depression would be linked to a SmartSet for appropriate testing,

treatment and referral. For the 65% of patients with at least one positive trigger, the team

has contacted nearly half by phone for further assessments and to make algorithm driven

recommendations and referrals.

Research-Related: Relatively little use for research thus far, but collaborating with the KP

Institute for Health Research and others. There is a no-call list for patients who have opted

out of research participation. A waiver of consent for research is applied to the remainder.

Quality Improvement: Metrics are developed as required by Medicare, including for

depression and anxiety. There are links to other programs such as a depression care

management team, and a CMMI funded COMPASS project using team care. No PRO

related dashboards or pay-for-performance yet.

Future Plans: Expand to other KP regions including KPNorthwest, KPGeorgia, and

KPSouthernCalifornia. Increase branching logic for PRO measures. Complete an inter-

regional data repository. Increase capacity for use of tablet computers for in-clinic data

collection. Develop history tool to be collected on a one-time basis at enrollment. Increase

automation for generation and printing of Personalized Prevention Plans and data flow to

reduce staff burden. Results of these efforts include identifying patients that receive a large

number of pre-visit PRO questionnaires and scheduling them to come in 20 minutes

earlier.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

30

KPCO: Health Risk Assessment scores from Integrated Voice Response in EpicCare

Walk-through of the Patient Assessment Process

The process begins when a member calls for a non-urgent appointment or is scheduled for

an annual wellness visit (AWV). If the patient is on KP.org the call center assistant assigns

a THA to be completed 1-2 weeks before the visit; if not, it does warm transfer to IVR

system. The data goes into the KP Health Connect EHR, and are summarized in Health

Trac. Positive triggers go to Senior Assessment nurses who call patients to obtain more

information. Medical assistants use data to complete a PPP which is put into Health

Connect including instructions to print a copy for the provider. All information is available at

the time of the patient visit ready to be used by provider. SmartSets make evidence-based

recommendations and make documentation easier. If THA is not done before the visit, it is

assigned to be completed the day after. Data are stored in Clarity and can be extracted for

research and QI.

Key themes

50% of patients age > 65 are on KP.org

Warm transfer at scheduling of Annual Wellness Visit assures that patients not on

KP.org complete Total Health Assessment using IVR

PRO data from THA collected both via KP.org and IVR are fully integrated into EHR

Important enablers: CMS mandate to add a Total Health Assessment to the Medicare

AWV; Central Program Office support with investment in IVR; building at regional level;

cost effectiveness analysis

Barriers: Limited functionality of EHR, lack of universal internet connectivity in facilities

Sources: KP internal documents; discussion (Matt Stiefel, Wendolyn Gozansky, Eric Mayer)

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

31

Minnesota Community Measurement (MNCM) – Essentia Health System

Basic System Summary

The MNCM system is free-standing statewide data collection effort that includes PRO

measures. MNCM is a non-profit organization that emerged in 2002 out of a community-

wide need for a consistent way of measuring and reporting health care quality measures

to the community. Minnesota’s health plans were already working together to sponsor the

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) for quality improvement. The medical

directors of these health plans wanted a single, combined report to compare patient care

and outcomes statewide, including public reporting. An explicit goal is to support the CMS

triple aim of improving Health, Experience, and Cost. Their first performance report was on

diabetes care; by 2004 results were published on the public website MNHealthscores.org.

Capturing patient experience of care has included the PHQ-9, the Asthma Control Test

(ACT), Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ), Asthma Control

Questionnaire (ACQ), functional status tools for Knee Replacement and Spine Surgery.

EHR Integration:

Data are collected electronically at each site, but are not necessarily integrated into local

EHRs. At Essentia Health, a health plan that includes 18 hospitals and 68 clinics and that

utilizes MNCM, data are increasingly collected via the Epic “MyHealth” patient portal (25%

enrolled). The remainder are collected during patient visits, or mailed paper questionnaire,

or phoned to complete data collection. Quality metrics are built in to their Epic EHR. Data

are exported to an external Quality Data Warehouse.

Clinical Practice

MNCM works with many clinics, hospitals, and medical groups in Minnesota, Wisconsin,

and North and South Dakota. At Essentia, depression screening using PHQ-9 is linked to

a Depression Clinical Workflow Guide provided by ICSI, and a Help and Healing online

toolkit that gives providers evidence-based treatment guidance and easy-to-use resources

to assist in depression recovery. Some of the Essentia clinics have specially-trained RN

care managers to work one-on-one with patients who have depression.

Research-Related:

MNCM is a grantee of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Aligning Forces for Quality

(AF4Q) program.

Quality Improvement

:

The PHQ-9 based performance measure has been endorsed by NQF. Currently, MNCM

reports on over 76 measures at over 315 medical groups and 672 sites of care. Reporting

of PRO measures is linked to statewide quality improvement programs such as DIAMOND

(Depression Improvement Across Minnesota). At Essentia Health, quality metrics are built

into the EPIC EHR and are used by the performance improvement team.

Future Plans:

Long-term goals are to expand to include both cost and experience of care, and Additional

PRO measures for spine surgery, total knee replacement, and others.

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

32

Essentia Health: After answering questions, patient can review and edit answers

Walk-through of the Patient Assessment Process

At Essentia Health, all patients with a recent visit diagnosis of depression complete the

PHQ-9 at a minimum of every 6 months. A total of 25% of Essentia patients are enrolled

on the Epic “My Health” patient portal. For patients with depression, if the patient does not

complete the PRO online, an aide calls or mails them to obtain the data. PHQ-9 data are

integrated into EpicCare EHR with standardized workflow for evaluation and treatment.

Quality metrics are calculated and addressed by the local quality improvement team and

are also reported to the State report card.

Key themes

Measurement of PROs supported by pay-for-performance at most health plans

Reporting is made mandatory by Minnesota Department of Health

Data collected at clinics and health plans; results are fed back and made publicly

available

Sources: Website, discussion (Tina Frontera MNCM COO; Patrick A. Twomey, MD CMO

Essentia); http://mncm.org/

; http://MNhealthscores.org/; http://mncm.org/submitting-

data/provider-tools/

©2013EpicSystemsCorporation.

Usedwithpermission

Advances in the Use of Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Electronic Health Records

33

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Basic System Summary:

The UPMC system is a PRO data collection system built upon the Epic EHR. In 2004, this

group implemented a standardized electronic intake system in an academic general

internal medicine practice for collecting PROs and other patient data (exercise, smoking

status, review of systems). The results from this 10-year effort have laid the foundation for

a health system-wide initiative to integrate PROs into the health care system. In the next 5

years, electronic clinical intake, including PRO and patient history collection, will be

integrated into UPMCs EHR across 861 outpatient practices in 35 counties.

EHR Integration:

PRO data collection is integrated into Epic, through MyChart and Welcome. Patient

questionnaires are seen by the clinician within the visit navigator, allowing item level and

total scores to be displayed to the clinician, and are available in a flow sheet for review