THE

NEW YORK

NEWS MEDIA

AND

THE

CENTRAL

PARK RAPE

Linda

S. Lichter

S. Robert

Lichter

Daniel

Amundson

13

•

V

1^1

THE

AMERICAN

JEWISH

COMMITTEE,

Institute

of

Human

Relations,

165

East

56

Street,

New

York,

NY

10022

2746

CENTER

FOR

MEDIA

AND

PUBLIC AFFAIRS

«ft / ^\ A^L

2101

L

Street.

N.W.

•

Suite

505 •

Washington,

D.C.

20037 V. \i• / C (7 ^7

Linda

S. Lichter,

Ph.D.,

is a

sociologist

specializing in public opinion and political

sociology.

S.

Robert

Lichter,

Ph.D.,

is a political

scientist

specializing in

mass

media and research methods. They

are co-directors of the Center for

Media

and Public Affairs in Washington,

D.C.

Daniel Amundson,

a graduate

student

in

sociology

at George Washington University, is research director at the Center.

Copyright

© 1989 The American Jewish Committee

All

rights reserved

Executive

Summary

The

rape of a jogger in New York's

Central

Park

this spring touched off a controversy over the

media's reporting of

interracial

crimes. Charges

of

sensationalism and racism were raised and debated.

We

have analyzed the topics, themes, and language of local media coverage for two

weeks

after the

attack

(April

20 to May 4). Using the method

of

content analysis, we examined 406 news items in New

York's four daily newspapers, the weekly Amsterdam News, and evening

newscasts

of the

city's

six

television stations.

Although

the

racial

element was conspicuous in this

story,

the content analysis found no evidence

that

media coverage played on

racial

fears or hatreds. On the contrary, the question of race was

repeatedly raised in order to

deny

its relevance to the crime, to warn against reviving

racial

tension, and

to call for a healing

process

to defuse

racial

animosity.

The

study

located several other elements, rooted in traditional news values, that help account

for

the

heavy and emotionally intense "play" the

story

received. These include the randomness and brutality of

the crime, the youth and reported personal and social stability of the

suspects,

and the "human interesf

inherent

in the victim's struggle to recover.

Nonetheless, a troubling

aspect

of the coverage was the use of highly negative and emotional

language

to describe the

suspects,

including frequent aspersions to their animality. The Post epitomized

this approach, but the

study

concludes that the

Post's

coverage was typical

of

a

populist tabloid.

Further,

by concentrating on the

story's

racial

angle, the media largely ignored the attack as a crime against

women-

Major

findings include:

* Race was mentioned as a

possible

explanation for the attack 54 times, more than twice as often

as any other factor. But its relevance was denied 80 percent of those times.

* There were only six references to the attack as a crime against women, that is, as a

demonstration of the perpetrators' virility or power over women or the treatment of women as

sex

objects.

* The crime was

most

often presented as a random act, a consequence of group dynamics, a

product of the subculture of "wild youth," or a result of negative media

messages.

* The

suspects

were described in emotional negative language 390 times, including 185

animal

images such as "wolves," "pack," and "herd."

*

The notion that

the

crime reflected

on the

city's

minority population

was

advanced only once

and

rejected

15

times.

*

Notwithstanding calls

for the

death penalty, greater prudence

by

runners

was

urged more often

than

stronger penalties

for

criminals.

The

study

also uncovered sharp differences

in

coverage

by

different media outlets. Among them:

*

The Post featured

the

most

coverage,

the

most

emotional language (twice

as

much

as any

other

outlet, averaging over three

animal

images

per

day),

and the

most

calls

for

getting tough

on

crime.

*

The Times

had the

least coverage among daily papers

and

the fewest negative descriptions

of

the

attackers, fewest expressions

of

adverse public reaction,

and

fewest calls

for

increased

law-

enforcement efforts. But

the

Times carried denials that

racial

factors were relevant twice

as

often

as

any

other outlet.

*

The Amsterdam News ran

the

most

comparisons

to

previous

racial

violence, identified

the

suspects'

race more often than

any

other outlet,

and

printed

the

most

charges that

the

(white)

media's coverage

was

based

on

racial

factors.

The

study

concludes that

the

coverage

was

split between

a

populist tabloid approach (emotional

language, focus

on

public outrage,

and

calls

for

"law

and

order" measures)

and

concerns about social

responsibility

(the

frequent denial that race

was

relevant

to the

crime).

But

by

treading

so

lightly

on the

race

issue,

the

media

missed

an

opportunity

to

confront

the

racial

undertones that well

up

in

cases

of

interracial

violence, even when

no

overt

racial

motive

is

present.

In

place

of

emotional coverage that

denied

the

relevance

of

race,

a

calmer approach that probed more

deeply

into race relations might have

better served

the

twin goals

of

good journalism

and

good citizenship.

A

Crime

and the

Response

Interracial

violence animates and divides New

Yorkers

more than any topic on the

urban

landscape. It

becomes

a

kind

of

Rorschach

inkblot onto which the city's residents project their fears

and

fantasies. In notorious

cases

from

Howard

Beach to

Tawana

Brawley,

those

reactions have been

partly

guided (or goaded) by the city's lively and diverse

news

media. It is almost inevitable that

the media coverage of

such

highly

sensitive

and divisive incidents

will

itself prove

controversial.

And

so it was with the story of

"wilding"

in

Central

Park.

The

facts of this

case

are relatively simple. A young white female jogger was raped and severely

beaten in

Central

Park

on the night of

April

19, 1989, in a

series

of

assaults

by the same group.

The

first

news

stories appeared the morning of

April

20 as the victim lay in a coma.

That

day and

the next, eight black and Hispanic

teenagers

were arrested and charged with the attack. Meanwhile,

the term

"wilding"

began to grip the imagination of headline writers to describe the

series

of attacks.

On April

23, public reaction heated up after the

suspects

were reported to have boasted that the

attack was

"fun."

Vigils

were held at the place of the attack and elsewhere.

On April

24

Mayor

Koch

and

Governor

Cuomo began to speak out against violent crime and

call

for new measures to deal with it. On

April

26 and 27 the first indictments were handed down.

The

last few days of the month saw outpourings of sympathy for the victim and outrage against the

attackers.

Cardinal

O'Connor

visited the

victim,

who had begun to emerge

from

her comatose

state.

And

Donald

Trump

ran a newspaper advertisement calling for restoration of the death penalty.

During

the first days of

May,

the victim showed further

signs

of recovery, and the media reported

several rapes of young women in

Harlem

and a sexual assault on another jogger in

Central

Park.

By

this time the city was in an

uproar

over the

case,

which continued to receive heavy press

coverage. Not

surprisingly,

that coverage was itself

drawn

into the controversy.

Critics

charged that

its emotionalism was sensationalistic at

best

and racist at worst.

Concerned

about the

effect

on interracial

tensions

in New

York

of media coverage of just such

an

explosive incident as the

Central

Park

rape, the Institute for

American

Pluralism

and the Center

for

Media

and Public

Affairs

undertook a study and evaluation of the press and television coverage

of

that

event

We did so by means of content analysis, a method of studying how information is

conveyed. Coders tabulated the topics, viewpoints, and language of

local

media coverage

from

April

20 to May 4, the first two

weeks

after the attack. The

outlets

examined were the major daily

newspapers ~ the

Times,

Post,

Daily

News;

the

Amsterdam News,

a weekly paper aimed at the city's

black

community,

and the evening

newscasts

on television

stations

WABC, WCBS, WNBC, WNYW,

WWOR,

and

WPIX."

The study included editorials, signed columns, and

letters

to the editor in

addition

to straight

news

stories, because

these

forums of

opinion

were an integral part of the media

treatment, especially in the tabloids.

Amount

of

Coverage

In

fifteen days,

from

April

20 through May 4, the 11

outlets

we examined

carried

406

news

items (table 1)." These included 313

news

stories, 42 editorials or signed columns, and 51

letters

to the editor. In the newspapers, which ran 190

news

stories overall, the crime was front-page

news

34 times. The heaviest

print

coverage was the

Post's,

whose

957 column inches included 46

news

stories, 13 editorials or columns, and 42

letters

to the editor. The printing of so many

letters

was

in

itself a

kind

of editorial statement. The

Daily

News

nearly matched the

Post

in space allocated

to the story (948 column inches) and exceeded it in

news

and editorial coverage. It was the

profusion

of letters, which functioned mainly as a sounding

board

for popular outrage, that set the

Post

apart. The

Post

also led all

outlets

in the prominence accorded the story, with 12 front-page

headlines. By contrast, the

Times

ran only 24 stories, including two on the front page, and five

editorials or op-ed pieces.

Even

the weekly

Amsterdam News

printed 13 items, including four

news

stories on the front page, in the two

issues

included in our sample period.

Broadcast

coverage was equally diverse.

WABC

was the clear leader, with 45 stories totaling

over 83 minutes of airtime.

That

was more than

half

again as much time as any other station

devoted to the story. The other major network affiliates

(WCBS

and

WNBC)

ran fewer stories

combined

than

WABC

Among

the independents, Fox's

WNYW

led with 28 stories lasting nearly

55 minutes.

WWOR

and

WPIX

lagged far behind with only 16 stories

between

them.

Print

coverage totaled 3,415 column inches, broadcast

news

4.25 hours.

"

We analyzed the

April

29 and May 5

issues

of the

Amsterdam News,

because the

April

22

issue

went

to press too early to include any mention of the attack.

Among

the television outlets,

we analyzed the 6:00 p.m. broadcasts of

WNYW

and

WPIX

and the 10:00 p.m. broadcast of

WWOR.

"

We were unable to procure the May 3

issue

of

Newsday.

Topics

Media

attention quickly transcended the facts of the crime and the subsequent police

investigation. The most heavily covered topics were neither of

these,

but rather the victim's story

and

public reaction to the attack (table 2). The victim's uncertain recovery became a compelling

human-interest story that extended the

normal

period of press attention. But even this was eclipsed

by

coverage of the public reaction to the assault

The

assault gripped the public emotionally, and it

seemed

for a time that every New

Yorker

had

both an opinion about it and the opportunity to

express

that opinion to a reporter, litis was

a

specialty of the

Post,

which ran 48 items dealing with public reaction, twice as many as any other

outlet (By contrast, the

Post

gave

only passing coverage to the victim, about

half

as much as the

other two daily tabloids.) The

Times

stood out among dailies for its lack of coverage in

these

areas -- only six stories on the victim and 16 on public reaction. The weekly

Amsterdam News

also

had

a distinctive profile, with no stories on the victim or the facts of the crime, only one on the

police investigation, but eight on public reaction. As we shall see, this paper's idiosyncratic

approach

to the story set it apart

from

the dailies.

Among

the television outlets,

WABC

stood out by offering over twice as much coverage as any

other station on the victim's

background,

her recovery, and the public's reaction. The other

stations

concentrated their airtime on more traditional crime-story topics, such as the attack itself and the

ongoing police investigations (though

WABC

led in covering even

these

aspects).

The

print

media differed most markedly

from

television in considering the attack in the context

of

broader

social problems.

Thirty

stories dealt extensively with contextual

issues

like the

racial

and

class

disparities in New

York,

government cutbacks in social programs, and the difficulties that

working

parents have in monitoring their teenaged children. All but two of

these

stories (93

percent) appeared in

print.

The leading source of social-context stories was the

Post,

with 11.

Framing

the

Story

We

move

from

the

broad

contours of coverage to its substance. We asked first whether the

media

presented the crime in terms of

certain

conceptual frameworks that structured the audience's

perception of it ״ as a

racial

crime, for instance, or a crime against women, or an example of a sick

or

lawless

society. It was not enough to mention such a factor in passing; it had to be directly

related to the nature or larger meaning of the crime. Most coverage did not use such a framing

device; it was absent in 74 percent of

print

and 97 percent of broadcast stories.

Eight

such conceptual frameworks were identified, although

some

were introduced only to be

rejected (table 3).

Chief

among them was the randomness of the attack, which the police called a

"crime

of opportunity." The crime's apparent lack of purpose or meaning beyond immediate

gratification

was cited 19 times, far more than any other factor.

On

May 2, for example,

Times

columnist Tom

Wicker

wrote: "Ironically, the crime itself

does

not

seem

to have been stereotypical ״ committed by

drug

addicts or hardened

street

criminals,

drug

related or racially motivated, or the product of definable social conditions." He concluded that the

crime

was "a chance

event

that could have happened to anyone unfortunate enough to have crossed

the path of the wilding youths." Two days later, the

Times

repeated the point in an unsigned

editorial:

"Those arrested evidently did not act out of

racial

hostility, involvement with drugs or

economic deprivation.

They

apparently believed they could get away with random brutality."

Tied

for second, with 11 mentions each, were the notions that this was either a sexually

motivated crime or an instance of interracial violence (without

racial

motivation). Almost as

frequent, with ten mentions, were stories that portrayed the attack as an example of

wild

or

lawless

youth.

For

example, one

Newsday

story

(April

25) began,

"Driven

by rage, sexual lust and boredom,

free-floating bands of

restless

youths have preyed on New

York

City

neighborhoods for a decade,

say social workers and

urban

crime experts." An additional nine stories considered the crime within

the framework of

racial

conflict.

Finally,

five

news

items portrayed the crime as an example of our "sick society," and another

five

raised

the

issue

of violent crimes against women (beyond merely describing the crime as a

sexual assault). The arguments about a sick society ranged

from

discussions of the

case

at hand

to critiques of the underlying social conditions alleged to produce such behavior.

For

example, the

Times

published (May 1) an op-ed piece by Elizabeth Sturtz that charged: "These kids look into

the future and see nothing promising.

They

breathe the contagion of violence in a society where

guns are worshiped and material objects and self-gratification are made to

seem

the aim of life."

In

an era of heightened feminist consciousness, it is notable that complaints about the

prevalence of crimes against women were raised so rarely, indeed no more often than charges of a

generalized social sickness.

Very

few sources echoed the opinions of a

Harlem

woman quoted

(April

26) in the

Daily News:

"It's a male and female thing. ... That's what this is about.

This

happened to a woman"; or a female jogger quoted

(April

21) in

Newsday:

"I've heard that stuff

about joggers being

safe

because they don't

carry

money before.... But a woman can't leave home

the thing the perverts and the two-legged animals want most

—

their sexuality. ... a woman who

runs

here at night is like

Bambi

in hunting season."

Explanations

With

the early arrests of

suspects,

the story quickly became

less

a whodunit than a "whydunit."

Why

the crime occurred became the central question that animated media coverage (table 4). The

279

responses

that were printed or aired ranged

from

the

suspects'

motives or mindsets to systemic

factors that either predispose young people to violence or

fail

to prevent it

from

occurring.

The

vast majority of proffered explanations were simply asserted or affirmed. But we also noted

those

whose

relevance or validity was denied.

Race

was the explanation discussed most often in the media. It was cited 54 times, more than

twice as often as any other possible cause. But its relevance was denied on 43 (80 percent) of

those

occasions.

More

than a

third

of

these

denials (14) appeared in the

Times,

but the pattern

was similar in every other outlet

except

the

Amsterdam News,

which provided equal space to

those

who affirmed and

those

who denied the relevance of race.

Thus

on

April

26 the

Times

quoted a teenager

from

the

suspects*

neighborhood:

"This

is not

a

black and white

issue.

They

hurt a woman and race is a cover-up. The are just bad kids." The

same day the

Daily News

quoted an East

Harlem

mother: "No color mattered. It ain't about black

and

white. It's a male and female thing. The victim,

she's

a human. That's what this is about.

This

happened to a woman." Two days later the

Times

quoted a mother of two to the same

effect:

"It wasn't a group of blacks and Hispanics who raped this white woman, it was a group of

children

who raped this woman. I think they would have been as vicious with a black woman."

No

television outlet ever asserted a

racial

motive, while

seven

broadcast

statements

specifically

denying

it.

The

overwhelming rejection of a

racial

motive is unusual in media coverage of such an

event.

Our

previous

studies

indicate that sociological explanations of

events

tend to be countered by

competing explanations rather than simply and repeatedly denied. It

suggests

a

kind

of

"Lady

Macbeth

syndrome," with the media providing a forum for sources concerned to

defuse

racial

tensions

exacerbated by a particularly abhorrent crime. Among the sources denying any

racial

motive

were

Mayor

Koch,

mayoral candidate

David

Dinkins, the police, and church leaders. Of the

four

unattributed

statements

to this

effect,

three appeared in the New

York Times.

We deal with

the media's treatment of the

racial

dimension in more detail below.

After

race, the explanations mentioned most often

were

the group dynamics or mob psychology

of

the attackers, the antisocial subculture of youth

gangs,

and the

thesis

of a "random act" - the

notion that this was an aberrant or otherwise unpremeditated crime. (This category included

reports that the

suspects

themselves

cited

"fun"

and "boredom" as their

motives.)

Typical

of the group-dynamics explanation was a

Daily News

quote

(April

25) from a psychiatric

social worker: "It's basically like a feeding frenzy by sharks. You get a group disinhibition where

any conscience or moral controls that would prevent them from going out and doing anything they

want -

even

murder ~ completely break down. There are no more rules." Sources who blamed

the attack on contemporary youth culture tended to

echo

a writer on children's

issues

who argued

(April

28) in the

Times:

"There is in this city among

teen-agers,

white and black, something that

is anarchic They feel that anything

goes,

that all the rules have broken down."

The

notion of randomness was

sometimes

brought to fend off the topic of sociological

explanations cited below.

For

example,

Newsday

quoted

(April

25)

Mayor

Koch's

statement:

"That's

what it is - a gang-bang rape. You name one

society

[sic] reason that you can

give

to explain

that. Most kids don't commit crimes.

You're

talking about an aberrant group." At other

times

the crime's very randomness was treated as a sign of a troubling,

even

chilling sociological

phenomenon. Thus another article in the

same

issue

of

Newsday

quoted journalist Bruce Porter:

"These are just kids erupting. There really is not a precedent for this

kind

of unfocused rage. We

are

seeing

the fiery tip of something we haven't explained."

These explanations

were

followed in frequency by a number of more traditional sociological

background

factors ״ poverty, drugs (the pattern of violence associated within the

drug

subculture),

media

messages

that encourage violent behavior, family breakdowns or inadequate parental

supervision,

cuts

in government social programs, and social

class

(have-nots

striking out against the

haves). Some of

these

broadened out into lengthy perorations about the misdirected social policies

that plant the

seeds

of violent crime. For example,

Pete

Hamill

charged in the

Post:

"Under

Reagan,

violence became entwined with policy. You don't like the Sandinistas?

Fine:

Kill

them.

Having

trouble in Beirut? Shell them. Don't care for the government in Grenada? Get rid of

them at gunpoint. If violence was permissible for the government, who in government could lecture

the

American

young to be pacific?" Dr. Roscoe

Brown,

Jr.,

was quoted (May 6) in a similar vein

in

the

Amsterdam News:

[New

York]

has not learned that the violence and disrespect for the basic human

needs

and values we see and hear daily on sensationalized television programs and

in

the multi-colored headlines of our

town's

newspapers

sends

a

message

about the

low value we place on human dignity. ... So should our city be surprised that a

group

of

Black

and Hispanic youths acted out the violent rage that has been

nurtured

by our media and the way the city

treats

its citizens?

Explanations

related to the attackers' poverty and the

drug

subculture

were

debated and rejected

about as often as they

were

affirmed. For example, the

Daily News

reported

(April

25)

Mayor

Koch's

rejection of the crime and poverty linkage: "The mayor said he refused to accept poverty

or

discrimination as the root

causes

of the attack. 'Poor people overwhelmingly don't commit

crimes,'

he said."

References to the media's role mostly referred to concerns about violence in television, movies,

and

rap music. For example, a

Post column

cited

(April

24)

Cardinal

O'Connor's

complaint about

"the inordinate power of television and movies that glorify sex and violence."

And

the

Times

quoted

a

Johns Hopkins professor who warned: "Dim and troubled people

will

take very powerful

suggestions

from

the media.... How can the

criminal

values of many of the action

shows

help but

have an effect?"

Thus

the assault was most often explained as a random act or a product of

group

dynamics (25

citations apiece), followed closely by youth subculture (24) and the negative impact of media

messages

(20).

This

debate was

carried

on mainly in the newspapers, where six out of every

seven

explanations (86 percent) appeared. The only explanations offered with any

frequency

on television

were race, youth culture, and "random act."

The

assault was

least

often explained in terms of male-female relations and

minority

subcultures.

We

found only six references to the abuse of women as evidence of

virility.

One reference made

in

passing is worth noting. It came in an

April

24

Newsday

interview with a

Brooklyn

Bad Boys

Club

member: "If you are any

kind

of

bad

boy, you don't need to do that to a

broad.

There's too

many

broads wild to do it already. All you got to do is be holding. That's what money is for

—

clothes, women, fun, get high."

Minority

subcultural models, which are often used to explain

patterns of violence, the second-class

status

of women, etc., within

urban

populations, were offered

only

twice and rejected both times.

Exploring

the

Racial Angle

A

persistent theme in media coverage of the assault was concern that the crime and its

aftermath

would worsen relations

between

blacks and

whites

in New

York.

We coded every

viewpoint published or broadcast about the impact the crime might have on any aspect of life in

the city (table 5). By far the most common view was the fear that it would increase

racial

tension

or

encourage negative

stereotypes

of nonwhites. As 15-year-old Kai Lewis put it

(April

26) in the

Post,

"We aren't all like that and I hope people don't stereotype us as being like

those

kids."

This

opinion

appeared 29 times; nearly

half

the citations (13) appeared in the

Times; Daily News

reporter

Mike

McAlary

developed this theme at length on

April

26:

The

phone lines to this newspaper are busy with people screaming,

"Call

the

case

for

what it is.

Black

savages

rape white

girl."

No one is even making an attempt

to mask their racism. . . . Manhattan prosecutor Robert Morgenthau . . .

announce[d] that the

case

had nothing to do with race. But no one wanted to hear.

The

newspapers came out in the morning and we have a bias incident complete with

the quote: "Let's go get whitey." It's doubtful, I am told, that the words were even

said...

. But the words are right there in the newspaper, stamped into our brains.

Now

mothers in East

Harlem

. . .

find

themselves

on

trial.

Discussions of the crime's impact on

criminal

justice finished a distant second, with 12 opinions

expressed. These included calls for toughening the juvenile-justice system, restoring the death

penalty, and preventing vigilantism.

As

if in response to such concerns, several other race-related

themes

appeared repeatedly in the

coverage. The most frequent of

these

concerned the need to heal

racial

wounds opened by the

attack. Such

statements

appeared 22 times, split almost evenly

between

print

(12) and television

(10). For example, the

Times

quoted

(April

26) the president of the Schomburg Plaza Residents*

Council

(where several

suspects

lived), who led a prayer

vigil

for the victim:

"Through

prayer we

can

heal the wounds on her body and the

racial

wounds this has caused to society.. . The need

for

racial

healing was featured most prominently in

Newsday

(six citations) and on

WABC

(five

times).

Nearly

as common was a rejection of the notion that this crime somehow indicted the black

community

as a whole or reflected negative

cultural

patterns characteristic of minority populations.

This

argument was advanced only once. It was rejected 15 times, most often in the

pages

of the

Post

(seven

instances).

Thus,

on

April

26 the

Post

quoted a black teenager: "I feel bad 1 have to

be associated with people like that. All blacks shouldn't be painted with the same

brush."

Similarly,

the

Times

quoted

(April

28) one Manhattanite: "People scream it's a

racial

episode, but

I

disagree. There are very good black people and very bad white people. .. ."

There

was greater willingness to interpret the attack as an indictment of behavior within

teen

subcultures. For example, the

Times

quoted

(April

26) a

Harlem

teenager:

This

is not

racial.

It

has to do with peer pressure.

Kids

follow each other.

They

wouldn't say this is wrong when among

friends."

Variations on this argument were raised nearly as often as the responsibility of the black

community

(13 times), but it was affirmed more often than it was rejected (54 to 46 percent).

Concern

over the impact of this incident on minorities even spread into the debate over the

justice system.

This

aspect of the coverage was mainly a

forum

for calls to "get tough" on crime

and

violent offenders. Nonetheless, the question of

racial

bias in the juvenile-justice system was

raised

11 times. We coded eight assertions that the system was biased against minorities, while

only

one source defended it against the charge (the others reached no conclusion). These charges

were raised most often by activists like Reverend Al Sharpton and attorney

Alton

Maddox

and by

one

suspect's

attorney. For example, the

Post

reported

(April

24) Sharpton's charge that "the white

teens

involved in the

Howard

Beach attack on a black man were granted

bail,

unlike

these

teens."

Another

indication of the media's sensitivity to

racial

issues

was the frequent comparisons of

the

Central

Park

assault to other interracial crimes (table 6). There were 55

print

mentions of

prior

incidents, led by

Howard

Beach (20), Tawana Brawley (8), and

Bernhard

Goetz (5). However,

only

33 of

these

sought to compare either the facts of the

cases

or the public's responses.

And

only

30 percent of the comparisons found

some

similarity

between

the current

case

and a previous one,

while 70 percent pointed out differences or warned against faulty comparisons.

By

far the largest number of comparisons appeared in the

Amsterdam News,

whose

two

issues

contained 43 percent of all comparisons. The

Amsterdam News

repeatedly counterpoised the

Central

Park

assault against instances of blacks attacked by white policemen or mobs, such as

Michael

Griffith

(Howard Beach)

Derrick

Tyrus,

Michael

Stewart, Akeem Davis, and even the

Scottsboro Boys

(seven

young blacks sentenced to death in

Alabama

in 1931 for

raping

two white

girls).

For example, the

April

29

issue

included an interview with the

suspects'

attorney

Golin

Moore,

who alleged a pattern of

rapid

arrests in black-on-white crimes but a lack of arrests in

white-on-black crimes. The story contrasted "fashion model

Maria

Hanson, Dr.

Kathyrn

Hinnant

of

Bellevue Hospital and the

Marshank

brothers of Staten Island, all of whom were attacked by

African

Americans," with the absence of arrests in the

cases

of "Tawana Brawley . . .

Derrick

Antonio

Tyrus

of Staten Island, . . . Akeem Davis of Brooklyn's

Park

Slope community, and

Frederick

Pinckley in

Williamsburg."

Other

sources were restrained in raising comparisons to other

racial

incidents, only six sources

pointing

out similarities and 12 denying them out of 393

news

items. For example, the

Times

ran

only

three comparisons (all to

Howard

Beach) and

Newsday

published only two (one to

Howard

Beach

and one to Tawana Brawley). All six television

stations

combined for only

seven

such

mentions, only one of which found a point of similarity.

Thus

״ with the exception of the

Amsterdam News

-- the reluctance to

find

a

racial

aspect to the crime extended to a reluctance to

find

points of comparisons to previous

racial

incidents.

Finally,

perhaps the ultimate

test

of the media's sensitivity to the

racial

angle was their

willingness to air complaints about

racial

bias in their own coverage. Most of the sources that

expressed concern about the heavy media coverage attributed it to

racial

attitudes

harmful

to

minorities.

This

argument appeared 40 times, split evenly

between

those

who asserted that the race

of

the victim increased the attack's visibility (22) and

those

who made the point indirectly by

asserting that black-on-black crime received

less

coverage than black-on-white crime.

Only

four

sources pointed to the victim's upper-class background as a reason for media interest, and none

linked

the amount of coverage to either the sexual nature of the crime or the amount of violence

involved.

The Amsterdam News

led with nine references to

racial

bias in the media coverage, all but one

criticizing

the lack of coverage of black-on-black crimes. The

Times

and

Daily

News

were

close

behind

with eight, although the

Times

took the opposite tack of pointing directly to the victim's

race in

seven

of the eight instances we coded. For example, the

Daily

News

quoted

(April

22) one

Harlem

resident: "If it were a black woman in a black neighborhood, no one would care about

this"; and four days later, another:

"You

wouldn't be here if she was black."

The Amsterdam News

went

further, publishing a lengthy front-page story on May 6 contrasting

this

case

with the recent rape and

murder

of a black woman in

Central

Park

that received

less

press

attention. The story quoted Reverend

Calvin

Butts: "We haven't heard a thing about this incident

in

the press....

This

is just another indication that

class

and race have a lot to do with the value

people put on life." And Father Lawrence Lucas was quoted as saying:

"This

is another example

of

the fact that in this society, the press, the police, district attorney and religious leaders consider

white life at a far greater value than black life."

This

alleged

link

between

race and

news

was the leading subject of controversy over the media's

handling

of the story. By comparison, only eight sources (led by the

Amsterdam News

with three

items)

complained about sensationalistic, irresponsible, or otherwise questionable media coverage.

As

in the debate over the crime

itself,

the

racial

angle dominated the debate over the media's

treatment of it.

For

all the hullabaloo over media attention to black-on-white crime, however, surprisingly few

stories even identified the race of either

suspects

or victim (table 7).

Only

41

news

items, one in

ten, identified the race of one or more

suspects,

and even fewer, 34 or one in 12, specified that the

victim

was white.

Moreover,

the outlet most likely to identify

suspects

as blacks was the

Amsterdam

News.

When

its nine references are deleted, the remaining media revealed the

suspects'

racial

background

only 32 times, or in one of every 12

news

items ~ the same proportion that mentioned

the victim's race. The number rises when accompanying pictures are included as identifiers

(especially for television). But even including both words and pictures, three out of four items

contained no information about the

suspects'

racial

background.

Negative

Language

If

the media were so careful to avoid or refute assertions that the actions of

these

youths

־10־

reflected more broadly on minorities, then why did the coverage prove controversial? The answer

is that objections were raised not so much to what was said as to how it was said. The quality of

language,

particularly

the use of

harsh

terms to describe the

suspects,

was itself

seen

as inflammatory

or

discriminatory.

As Congressman

Floyd

Flake

charged

(April

29) in the

Amsterdam News:

The

press clearly

gives

the impression of Blacks as being animals in a wolfpack. And by placing

these

young

men individually in the paper, the press did their historical stereotyping that inevitably leads

to more division among the various ethnic groups in the city."

To

evaluate this aspect of the coverage, we noted every instance of emotion-charged language

to describe the attackers or the crime itself (table 8). Negative imagery used to describe the

attackers or their behavior fell into four distinct categories: terms that evoked animality

(e.g.,

"wolfpack,"

"herd,"

"bestial");

criminality

("thugs,"

"gang,"

"crime

spree");

aggressiveness

("marauders,"

"war

party,"

"hungry for action"), and a catchall category of colorful negative terminology ("wildeyed

teens,"

"fiends,"

"these

goddamned people"). The repeated use of such language

gave

the coverage

a

heightened emotional or sensationalistic flavor.

Altogether

we counted 390

uses

of strongly negative words or phrases to denigrate the attackers.

Nearly

half

of this total, 185

uses,

consisted of animal imagery. For example, one

Daily

News

editorial

began: "There was a

full

moon Wednesday night. A suitable backdrop for the howling of

wolves. A vicious pack ran rampant through

Central

Park."

The references to animality were

perhaps typified by Congressman Charles RangePs

statement

(Amsterdam News,

April

29) that he

had

"never

seen

such an animalistic attack"; in fact, "calling them animals and wolfjpack is an insult

to animals and wolves." The

Post's

Pete

Hamill

made

(April

25) the same point in even stronger

terms by decrying "a bizarre new

form

of life... who

call

themselves

men ... the mutants among

us." He concluded,

"

And for now, we should

stop

libeling wolves."

The

second largest category of emotion-charged language, with 122 references, disparaged the

attackers by using

epithets

that evoked their

criminality.

A much smaller number of references (45)

focused on the attackers'

aggressiveness.

Finally,

there were

some

highly charged descriptions that

defied categorization, other than to

express

anger at the type of people who could commit such a

crime.

Of

course, many

pieces

combined several of

these

images. For example, on May 1 the

Posts

Mary

McGrory,

no hard-had conservative, was moved to

call

the attackers "life's losers," "a pack

..

. out

1

wilding,"'

"fiends," and "punks." A

Newsday

story on

April

24 condemned "wolf-pack stuff,"

and

"random pack violence." And in another column,

Hamill

called

(April

23) the group

"demented,"

"

a

savage

little pack," and

"these

brutalized little sociopaths."

As

these

examples

suggest,

negative characterizations were most prominent in the tabloids,

especially the

Post.

Just under 90 percent of them appeared in the newspapers, and the

Post

led

all

other

outlets

in all four categories, accounting for 30 percent of all negative imagery.

The Posfs

lead

in negative language was particularly pronounced in the catchall category of unusual colorful

phrases; its writers contributed 60 percent of this total. For example, on

April

25 columnist

Jerry

Nachman

likened the attackers to "an invading melanoma" and an "anonymous,

faceless

tumor

mass." The next day he came up with an even more graphic metaphor: a

"rolling

mass

of pus."

But

this couldn't top Hamill's grisly image

from

April

23: "And then, out of the New

York

darkness,

comes

the lewd and wide-eyed mask of death.

Grinning."

Even

this outpouring of obloquy against the attackers was dwarfed by denunciations of the

attack

itself.

The brutality and randomness of the crime were repeatedly evoked in verbiage that

expressed outrage and

horror.

The number of times emotionally charged phrases were used to

depict the crime was nearly twice that of

epithets

aimed at the attackers (768 vs. 390). The phrases

-11־

fell

into three categories: descriptions of the violence

("savage,"

"bloody," "gang bang"), emotional

evocations of randomness

("senseless,"

"frenzy," "wilding"), and negative reactions to the

event

("chilling,"

"abhorrent," "outrage").

We

coded 322 references to the violence of the crime. The random or unprovoked quality of

the attack sparked 274 emotional references.

Finally,

172 references expressed the negative

reactions of the populace or the writer. For example, a

Times

editorial condemned

(April

21) the

attack's "savagery" and "atrocity";

Newsday

quoted

Mayor

Koch

on the "savagery" of "this terrible

crime

. . . this outrageous act"; the

Post's

Ray

Kerrison

decried "the appalling savagery" as

"obscene" and

"horrifying";

ana the

Amsterdam News

quoted an assistant district attorney who

claimed,

"This

was the most vicious and

brutal

assault that has occurred in New

York

City

to date."

Once

again, colorful language was mainly the property of the press (80 percent of all instances

vs. 20 percent on television). And the

Post

again led all other outlets, far outdistancing its

competitors in strong depictions of violence and negative reactions. It was the

Tunes,

however, that

led

in descriptions of randomness, reflecting its

extensive

coverage of the phenomenon of

"wilding."

Combining

terms applied to both the crime and the attackers produced an overall total of 1,158

instances of negative phrasing. The

Post

was the clear leader in emotionally charged verbiage with

309, about

half

again as many as any other outlet. Roughly similar

levels

were found at the

Times

(200),

Newsday

(211),

and the

Daily

News

(193).

Television lagged far behind, with emotion-laden

language evident roughly in proportion to each

outlet's

amount of coverage

—

highest at

WABC,

followed by the other network affiliates and then the independents.

The

Suspects'

Backgrounds

These

vivid

and frequent denunciations of the attackers and the crime were set against a

backdrop

of puzzlement over the apparent emotional and social stability of the

suspects.

Indeed,

reports of their "positive" personality traits or demeanors became a

kind

of ironic counterpoint to

the brutality of the crime with which they were charged (table 9).

We

coded 110 descriptions of the

suspects'

personal traits

prior

to the alleged attack. Ninety-

two of

these

(84 percent) were positive (including terms such as "non-violent," "decent," and "well-

adjusted"), and only

seven

(6 percent) were negative, and the rest were neutral.

This

retrain was

sounded most often in

Newsday

(28 times), although such characterizations appeared regularly in

all

the daily papers. Television mostly failed to develop this aspect of the story, with the exception

of

WABC

(which aired

half

of the 20 video references coded).

Thus

a

Newsday

story on

April

22 quoted one

suspect's

friend,

"They're good boys." The

reporter

observed,

"They

could be good

students

and polite

sons,

but they could be transformed

when surrounded by a wilding pack

...."

Nearly a

week

later another

Newsday

piece quoted

(April

28) one

suspect's

father, "He's a good

kid";

another's

girlfriend,

"He was nice and everything ... it

shocked me ... I knew him so well"; and the teacher of a

third,

who called him "well-behaved" and

"likable."

It is typical of crime coverage to eulogize the victim. In this

case,

however, the

suspects'

personalities were extolled even more often than the victim's (table 10). She was termed "pretty,"

"personable,"

"smart,"

"diligent," etc. only 70 times, although positive reports of her accomplishments

or

social potential ("rising star," "fast track," etc.) would

bring

the total up to 114 encouraging

words.

-12-

Obviously

the intent of this coverage was not to compare the

suspects

favorably with the victim.

It was intended to contrast the

brutal

behavior during the attack they

were

alleged to have

committed with their apparently exemplary behavior

prior

to it. But the comparison points out how

important

this contrast was to the story. It drove home the

theme

of "good kids turned

bad,"

which

contributed

to the

sense

that their alleged crime was shocking, unexpected, or incomprehensible.

Thus

the

Times

quoted

(April

28) one East Sider:

"That

was the first shock: They're average city

kids.

If they

were

street

kids you could blame it on poverty. In a

sense

they

were

anybody's kids.

Here

you don't know where to put the blame."

Similarly,

frequent references to the victim's attractiveness, intelligence, and once-bright

prospects heightened the dramatic contrast and strengthened the implication that no one is

safe.

Newsday

columnist Jimmy Breslin played on this contrast in an

April

21 column that raised the

specter of two New

Yorks

on a collision course: The young woman . . . could not, with all her

schooling and all her

success

. . . envision a kid like this. ... If she had realized that the other

New

York

throws out kids like this by...

tens

of thousands, she wouldn't have been running alone

at night in the

park."

Public

Reaction

If

there was an inflammatory quality to

some

of the language used to describe this story, the

pot was

also

kept boiling by reports of public outrage and associated calls for crackdowns on crime.

We

noted earlier that reports on public reaction provided the single most frequent topic of

coverage. We

also

measured the substance of

those

reports

(table

11). They served most frequently

as a means to convey public anger (41 instances), followed by expressions of shock (20), fear (20),

and

sorrow (19).

These accounts of public reaction provided one of the

best

indicators of differences in the flavor

of

coverage at the various media

outlets.

As we found with colorful language, this was a specialty

of

print coverage. The press ran two reports of public reaction for every one that appeared on

television (66 to 34). And

once

again, the

Post

led all print

outlets,

by an

even

larger margin than

its use of strong language. In fact, the

Post

ran

twice

as many public-response

items

(30) as any

other

news

organization. The

Post

was particularly prone to print expressions of anger at the crime

—

almost

twice

as many as the olher four newspapers combined. At the other end of the print

spectrum was the

Times,

which ran only three examples of citizen reaction.

Thus

on

April

25 the

Post

editorialized, "The anger sweeping through the city ... is a healthy

sign, an indication that New

Yorkers

are not yet willing to surrender their city to savagery." The

next

day a

Times

editorial began, "The

news

inspires

horror

and outrage." The

Post

columnist

Pete

Hamill

provided

(April

23) one expression of sorrow by quoting a black resident of the city,

Thing

like

that happens, it breaks everybody's heart - the family, friends, hell, anyone with

some

kinda

feelings." And in the

Amsterdam News,

Dr. Roscoe

Brown,

Jr.,

acknowledged that "all New

Yorkers

are repulsed and outraged by the

Central

Park

attack," before asking, "What is the value of

reiterating such phrases as Volf-pack' and

'savages'

in the press and on television?"

Differences among broadcast

outlets

were

equally striking.

WABC

(12) and

WCBS

(13) vied

for

the lead in airing expressions of public outrage, concern, etc., while

WNBC

refrained from

broadcasting any emotional reactions. The remaining

stations

confined

themselves

to recording a

few expressions of public anger. The emotional impact of man-on-the-street

statements

was, of

course, heightened by the visual medium. For example,

WABC

aired

(April

22) a denunciation by

a neighbor of a

suspect

who concluded angrily, "I got no patience with any of them. I hope you

get 'em!"

-13-

Preventing

Violent Crime

The

sharp differences among

outlets

in their use of language and reporting of public reaction

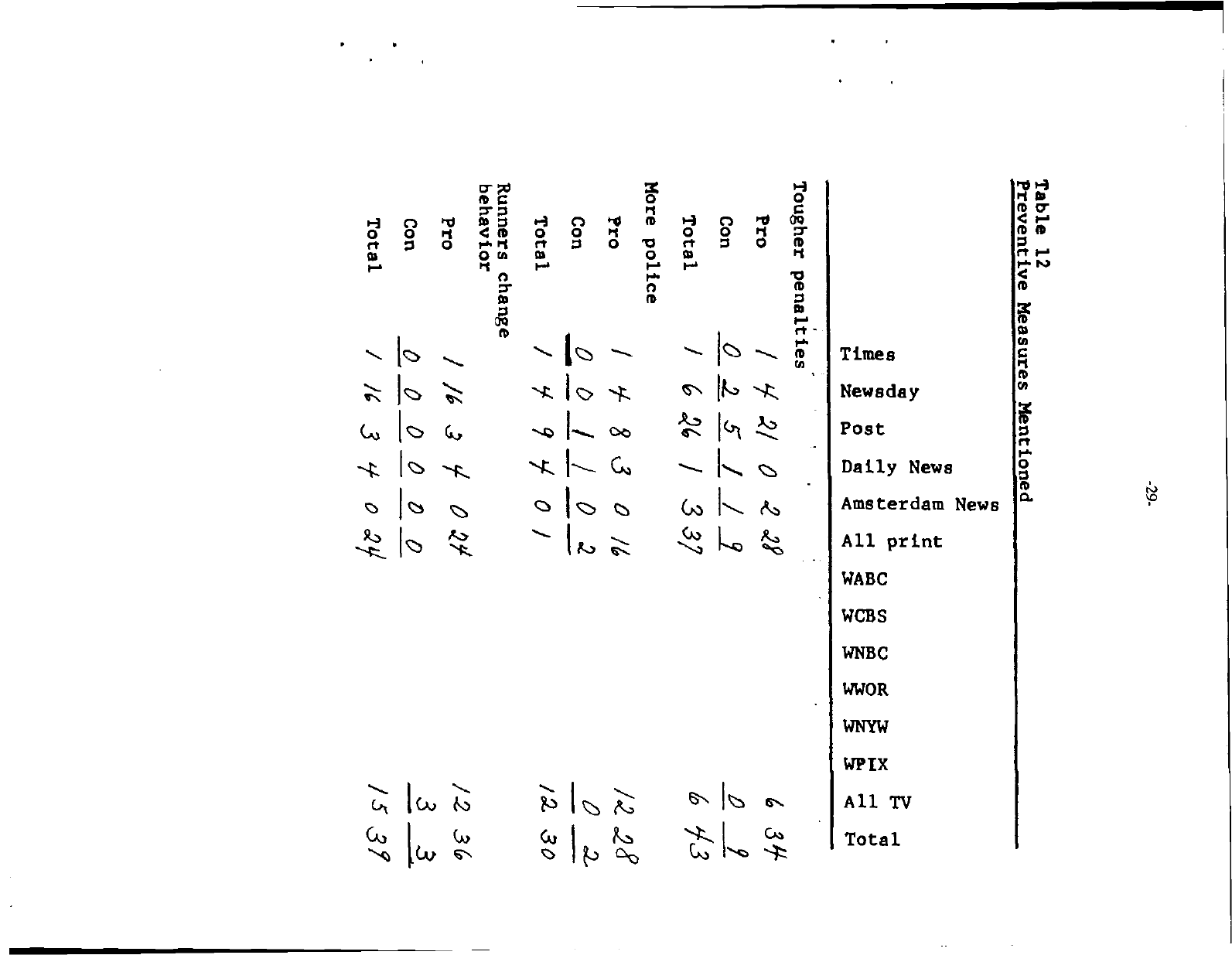

extended to one other controversial topic ״ media-borne calls for a crackdown on crime. We

analyzed

all discussion of measures intended to prevent future attacks of this sort (table 12). Most

of

these

concerned calls for tougher penalties, more police, or altering the behavior of

runners.

The

debate over tougher penalties received the most coverage. The 43 citations ran nearly four to one

in

favor of such measures as restoring the death penalty and trying juveniles as adults. (This did

not include Donald

Trump's

paid

advertisement,

except

when cited in

news

stories.)

Much

of this

debate took place in the

Post,

which accounted for 60 percent of

all

references to increased penalties

for

criminals.

Thus

on

April

23 the

Post

quoted extensively

from

Mayor

Koch's address to the

Columbian

Lawyers

Association, in which he called for treating juvenile offenders as adults: "Anyone who

committed this rape is not a

child.

They

should be subject to the

full

range of

imprisonment."

In

a

similar vein, the

Daily News

quoted

(April

28) Representative

Chuck

Douglas

(R-NH),

"If

you're

gonna do big boy crime, you're gonna do big boy time." And a

Newsday

story quoted

(April

30)

the headline of Donald

Trump's

newspaper ad,

"Bring

back the death penalty!

Bring

back our

police!" On the other side of the law-and-order

issue,

a

Times

editorial titled

"Lunging

for Death"

lamented (May 4) that

"some

people abandon talk of deterrence and speak of

primitive

vengeance.

.

. . The death penalty would only pander to an ugly mob mood."

An

associated theme was the need for more police or increased patrols in

Central

Park,

mentioned by 30 sources (including two who questioned the efficacy of such measures). Once again

the

Post

led with nine mentions. For example, on

April

23 it quoted mayoral candidate

Ronald

Lauder's

assertion that "an incident like this might not have happened" if there were more police

patrols in central

Park.

If

these

two categories are combined to

form

a single "law-and-order"

dimension,

the

Post

accounted for nearly

half

the discussion of stronger law-enforcement measures

(35 of 73 mentions, or 48 percent). At the other end of the

print

spectrum was the

Times,

with

only

two mentions, even fewer than the weekly

Amsterdam News.

Not

all the calls for preventive measures were calls for law and order. Greater prudence by

runners

was urged even more often than stronger penalties for criminals (by 36 vs. 34 sources

favoring

such measures). These measures were urged mainly by

Newsday,

which ran 44 percent of

all

suggestions

that runners avoid the

park

at night, stay below 90th Street, run in pairs, etc.

Typical

of this theme was advice

from

the often-quoted

Fred

Lebow, president of the New

York

Roadrunners

Club

(Newsday,

April

21): "If you run late in the evening, do not run above 90th

Street. Don't wear jewelry, don't wear a

Walkman.

If you've got to run at night run on the

Fifth

Avenue

sidewalk."

There

is an historical irony to this aspect of the coverage, because

Central

Park

was conceived

by

its creators as a place where all

classes

of people could peacefully mingle.

This

assumption

lasted well into the twentieth century.

Thus

the transformation of the

park

into a dangerous place

("the ultimate nightmare") holds

deep

resonance as a symbol of the breakdown of

urban

life. Hence

the

Daily News's

editorial cry on

April

22: "The city must struggle constantly to insure that

Central

Park

is open to everyone, all the time.... Retreating behind doors is like telling the wolf packs:

Go

on, the city is yours."

On

the subject of crime prevention, television was

less

in evidence than the newspapers, and

its priorities differed significantly

from

those

of the

print

media. Television aired only six sources

who called for harsher penalties, compared to 12 who advocated a greater police presence and 15

who debated the need for runners to change their behavior (12 favored such changes; 3 were

-14-

opposed). Television's contribution to this debate was headed by

WABC,

which aired eight of the

12 calls for more police and 11 of the 15 sources who debated the behavior of runners.

Conclusion

How

did the New

York

media cover the story of "wilding" in

Central

Park?

Our study

uncovered

a schizoid quality to the coverage, a split

between

the flamboyant populist approach of

tabloid

journalism and the concerns of social responsibility. The populist element surfaced in the

use of

colorful

and emotional language; the frequent reports of public outrage, which may feed back

into and intensify the public mood; and the calls for "law and order" measures. At the same time,

there was a continuing effort to defuse

racial

tensions

by denying that

racial

motives or interracial

differences were relevant to the crime.

Although

the

racial

angle played a major role in this story, our content analysis found no

evidence that the coverage played on

racial

fears or hatreds. On the contrary, the question of race

was repeatedly raised in order to deny its relevance to the crime, to warn against reviving

racial

tension, and to

call

for a healing process to defuse any

racial

animosity that might

exist.

The denial

of

racial

relevance was found not only in the

Times

but in the tabloids (including the

Post),

which

pushed the story much harder and in a more emotional vein.

Only

the

Amsterdam News

insisted

on

a

racial

angle, by presenting the crime and its coverage within the framework of white America's

injustices to blacks.

Indeed, one might argue that the media treatment of race cut two ways: they helped diffuse

tensions, yet they may have missed an opportunity to confront the

racial

undertones that well up

in

cases

of interracial violence, even when no overt

racial

motive is present.

WABCs

Jeff

Greenfield

recently argued (July 8) in the

Times

that race

is an

issue

that the political and journalistic establishment cannot or

will

not talk

about... race

seems

to take otherwise intelligent and thoughtful people and strike

them dumb, in both

senses

of that word ... I have heard ... last spring's

Central

Park

terror [linked] to the "poor role models" provided by

Richard

Nixon,

Oliver

North,

Ivan Boesky ... - as if the behavior of

these

public figures counted for a

tenth as much as the culture of remorseless violence that has become an epidemic

in

many black and Hispanic neighborhoods. [Race]

will

either be talked about

openly, honestly ... or it

will

remain underground, poisoning the wellsprings of

discourse, hidden in the whispers within the city's tribes, emerging only in the

form

of

angry denunciations across sealed borders.

Our

study located several other elements, rooted in traditional

news

values, that help account

for

the heavy and emotionally

intense

"play" the story received.

First,

the randomness of such a

brutal

crime fueled public fears. "Stranger crimes" are the most threatening, because they remind

people that they

themselves

(i.e.,

anyone) could have been the victim. A neighbor of one

suspect

put

it bluntly

(April

21) on

WABC:

"It could have been me. It could have been her. It could

have been anybody. If they'll do that person like that they'll do me, same way."

Second,

the youth of the

suspects,

combined with their reported positive personal traits and

stable social backgrounds, flew in the face of

traditional

explanations for such behavior. The "good

kids

go

bad"

story is a variant of the "man

bites

dog" turnabout that

lies

at the core of what makes

news.

This

aspect of the story was strengthened by widespread puzzlement and conflicting opinion

over why

these

kids

"went

bad." The apparent failure of traditional sociological categories to

account for this behavior added an element that was at once tantalizing and disturbing.

-15-

Overlaid

onto an already heightened concern with violent crime, this element also stoked fears

of

a city under

siege

by

criminal

elements, especially violent young males. The apparent

unlikelihood

of

these

particular

youths committing such a crime made the problem and associated

fear

(hence

the

news

value)

seem

much greater.

Third,

the victim's struggle to recover kept the

story alive by providing a daily

news

peg for continuing speculation, condemnations, and political

pronouncements, all duly reported.

The

central

news

value at work was unpredictability

—

the unusual brutality, the apparent

randomness of the crime, the unexpected inability to provide a standard sociological explanation,

and,

finally, the uncertain outcome of the victim's struggle to recover.

The

operation of traditional

news

values must be considered by

those

who would ascribe the

heavy and emotional coverage to more malign forces ranging

from

sensationalism to racism. But

this

does

not absolve the media

from

responsibility for the

news

judgments that shaped their

coverage. The

news

is not a

mirror

on reality but a

prism

whose

refracted images are formed not

only

by

events

but by the choices and perspectives of journalists and

news

organizations.

This

can

be illustrated most clearly by comparing coverage of the same

events

by different outlets. For

example, our content analysis revealed three quite different but internally coherent perspectives in

the

Times,

the

Post,

and the

Amsterdam News.

The

tone

of the

Times's

coverage was cerebral, conceptual, informed by sociological analysis.

A

majority of all "experts" quoted (58 percent) appeared in the

Times.

It also

seemed

aimed at

defusing tie passions aroused by the crime. The

Times

featured by far the

least

coverage among

the daily papers. It also ran the

fewest

stories on the public's reaction to the crime and the victim's

struggle to recover, thereby downplaying the story's empathetic elements. Significantly, the

Times

led

all other

outlets

in one major area - the rejection of race as an explanatory factor. In fact, the

relevance of race was denied in the

pages

of the

Times

at

least

twice as often as anywhere

else.

The

paper also featured only three comparisons to any other

case

of

interracial

violence.

Among

the dailies, the

Times

printed by far the

fewest

calls for increased law-enforcement

efforts, the

fewest

negative descriptions of the attackers, the

fewest

positive descriptions of the

victim,

and

fewest

expressions of adverse public reaction. Alone among the local press, the

Times

treated the crime as a

"normal"

story, a regrettable and troublesome

event,

but one that

carried

the

danger of rousing popular passions that might unleash

racial

hostilities.

The

Post

was the

paradigm

of everything that made the coverage controversial. It

gave

the story

the

full

tabloid treatment, replete with

blaring

headlines, editorial outrage, angry letters, and

impassioned prose. The

Post's

coverage was the heaviest of any outlet - 101

news

items (over

seven

per day on average). It

gave

the most play to public reaction and printed the most calls for

getting tough on crime. It used the most emotional language to describe the crime and the

attackers (averaging over three animal references per day) and to

express

public anger or aversion

(ten times as often as the

Times).

At the same time, the

Post

was second only to the

Times

in

rejecting the relevance of

racial

explanations, and it was second to none in

printing

denials that the

crime

indicted the black community.

Thus

the

Post's

coverage was not racist but populist in tone. A singular feature of the paper's

approach

was its willingness to

print

scores

of letters, many (but not all) agreeing with its editorial

expressions of outrage at violent crime and demands for swift and

severe

punishment. The

Post

seemed

to view itself as the

agent

for expressing public anger over the social breakdown associated

with

urban

crime, even as the

Times

sought to temper popular passions. Hence the

Post's

editorial

endorsement on

April

25 of "the anger sweeping through the city" as "one of the few encouraging

developments to emerge

from

that

obscene

episode."

-16-

The

Amsterdam News

provided an alternative populist perspective on the crime, one that drew

on

black suspicion of calls for "law and order" as implicitly racist. Ironically, that very perspective

made this the outlet most likely to focus on the crime through the prism of

racial

consciousness.

Despite running only one

issue

for every

seven

by the dailies, this weekly paper ran the most

comparisons to previous

instances

of

racial

violence, identified the

suspects*

race more often than

any other outlet, and printed the most charges that the

(white)

media's attention to the

case

was

due to

racial

factors.

The

differences in

these

three newspapers

were

perhaps

best

expressed in the divergent editorial

responses

to calls for a return to the death penalty. A

Post

editorial titled

"Channel

Your

Outrage:

Demand

the Death Penalty" asserted:

The

people of New

York

are no longer willing to be seduced by the claim that

society

is somehow responsible for the behavior of the

marauding

thugs

who terrorize

the city. New

Yorkers

are interested in swift and sure punishment, not in a groping,

pointless search for "root

causes."

The

Times

editorial on May 4 was titled

"Lunging

for Death." It condemned talk of

"primitive

vengeance," endorsed Governor Cuomo's

veto

of earlier capital-punishment legislation, and argued

that "the death penalty would only pander to an ugly mob mood." The

Amsterdam News

ran (May

6) a front-page editorial signed by editor in chief

Wilbur

Tatum

that called for

Mayor

Koch's

resignation:

With

the rape in

Central

Park

of a young white woman, Koch's

vitriol

rose to

another height and set another standard for indecency that trumped

Trump,

in

spades. . . . Quite apart from his lunatic advocacy of the death penalty screeching

so loudly in our ears that we hear "Death Penalty ... for

Blacks,"

we see this now

as Koch's reelection anthem, and

"KILL THEM"

as his flag.

Beyond

such obvious differences in the coverage, the importance of

news

judgment is illustrated

by

the story that no one reports, the angle that is not pursued. A good example is the

absence

of

reporting

on the

Central

Park

rape as a crime against women. Concern over the crime's interracial

aspect,

along with

random

violence or

"wilding,"

established a conceptual framework for the media's

coverage that virtually excluded concerns about gender-based brutality.

It was not until

May

5, over two

weeks

after the crime and long after its

context

was established

in

the public

consciousness,

that this argument appeared in fully developed

form.

In a

Times