1

Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., “The Blessing of David: The Charter for Humanity,” The Law and the

Prophets: Old Testament Studies Prepared in Honor of Oswald Thompson Allis, ed. John H. Skilton

(Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1974) 298.

233

TMSJ 10/2 (Fall 1999) 233-250

THE DAVIDIC COVENANT

Michael A. Grisanti

Associate Professor of Old Testament

The centrally important Davidic Covenant was one of the “grant”

covenants, along with the Abrahamic Covenant, in contrast to the Mosaic Covenant

that was a “suzerain-vassal” treaty. Second Samuel 7:8-16 articulates the Davidic

Covenant in two parts: promises that find realization during David’s life and

promises that find realization after David’s death. Though “grant” covenants such

as the Davidic are often considered unconditional, conditionality and

unconditionality are not mutually exclusive. God’s covenant with David had both

elements. Psalms 72 and 89 are examples of ten psalms that presuppose God’s

covenant with David. Various themes that pervade the Abrahamic, Mosaic, Davidic ,

and New covenants show the continuity that connects the four.

* * * * *

God’s establishment of His covenant with David represents one of the

theological high points of the OT Scriptures. This key event builds on the preceding

covenants and looks forward to the ultimate establishment of God’s reign on the

earth. The psalmists and prophets provide additional details concerning the ideal

Davidite who will lead God’s chosen nation in righteousness. The NT applies

various OT texts about this Davidite to Jesus Christ (cf. Matt 1:1-17; Acts 13:33-34;

Heb 1:5; 5:5; et al). In the Book of Revelation, John addresses Him as the “King of

Kings and Lord of Lords” (Rev 19:16).

Walter Kaiser suggests at least four great moments in biblical history that

supply both the impetus for progressive revelation and the glue for its organic and

continuous nature: (1) the promise given to Abraham in Genesis 12, 15, 17; (2) the

promise declared to David in 2 Samuel 7; (3) the promise outlined in the New

Covenant of Jeremiah 31, and (4) the day when many of these promises found initial

realization in the death and resurrection of Christ.

1

Ronald Youngblood’s understand is that 2 Samuel 7 is “the center and

234 The Master’s Seminary Journal

2

Ronald F. Youngblood, “1,2 Samuel,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, ed. F. Gaebelein

(Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1992) 3:880.

3

Walter Brueggemann, First and Second Samuel (Louisville: John Knox, 1990) 253, 259.

4

Robert P. Gordon, I & II Samuel: A Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986) 235.

5

Jon D. Levenson, “The Davidic Covenant and Its Modern Interpreters,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly

41 (1979):205-6.

6

Darrell L. Bock, “The Covenants in Progressive Dispensationalism,” Three Central Issues for

Today’s Dispensationalist, ed. Herb W. Bateman, IV (Grand Rapids: Kregel, forthcoming), 159.

7

Bruce K. Waltke, “The Phenomenon of Conditionality within Unconditional Covenants,” Israel’s

Apostasy and Restoration: Essays in Honor of Roland K. Harrison, ed. A. Gileadi (Grand Rapids: Baker,

1988) 124.

8

Moshe Weinfeld, “The Covenant of Grant in the Old Testament and in the Ancient Near East,”

JAOS 90 (1970):185; Waltke, “Phenomenon of Conditionality” 124.

focus of . . . the Deuteronomic history itself.”

2

Walter Brueggemann regards it as

the “dramatic and theological center of the entire Samuel corpus” and as “the most

crucial theological statement in the Old Testament.”

3

Robert Gordon called this

chapter the “ideological summit . . . in the Old Testament as a whole.”

4

John

Levenson contended that God’s covenant with David “receives more attention in the

Hebrew Bible than any covenant except the Sinaitic.”

5

After setting the background for the Davidic Covenant, the bulk of this

essay considers the OT articulation of that covenant. Attention then focuses on the

coherence of the various OT covenants, i.e., how they relate to each other and what

they represent as a whole.

THE BIBLICAL BACKGROUND TO THE DAVIDIC COVENANT

Different Kinds of Biblical Covenants

The Noahic, Abrahamic, Davidic, and New covenants are often called

“covenants of promise”

6

or “grant” covenants,

7

whereas the Mosaic Covenant is

likened to a “suzerain-vassal” treaty.

8

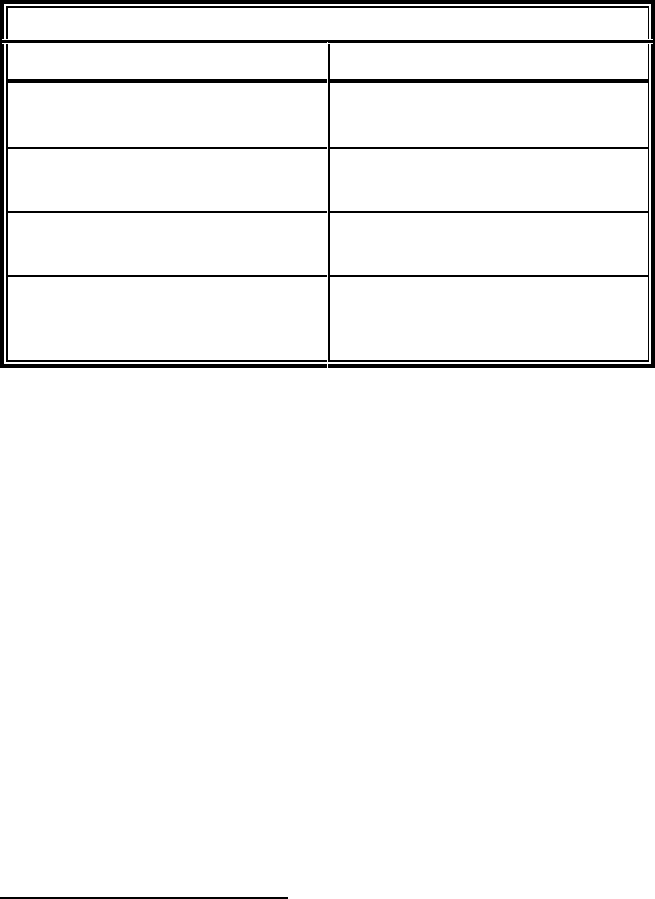

The following chart (Figure #1) delineates

some of the fundamental differences between the two types of covenants.

The Davidic Covenant 235

9

Richard E. Averbeck, “God’s Covenants and God’s Church in God’s World,” (unpublished class

notes, Grace Theological Seminary, Winona Lake, Ind., 1989) 13.

10

Bock, “Covenants in Progressive Dispensationalism” 160. Bock (159) comments, “[T]he program

begun with Abraham gives Israel a central role in God’s plan and represents part of God’s activity to

restore a relationship lost with man at the fall.”

Figure #1: Basic Differences between a Grant and a Treaty

Grant Treaty

1. The giver of the covenant makes a

commitment to the vassal

1. The giver of the covenant imposes

an obligation on the vassal

2. Represents an obligation of the

master to his vassal

2. Represents an obligation of the

vassal to his master

3. Primarily protects the rights of the

vassal

3. Primarily protects the rights of the

master

4. No demands made by the superior

party

4. The master promises to reward or

punish the vassal for obeying or dis-

obeying the imposed obligations

The Abrahamic Covenant

The Abrahamic Covenant is a personal and family covenant that forms the

historical foundation for God’s dealings with mankind.

9

Through this covenant God

promises Abraham and his descendants land, seed, and blessing. The Abrahamic

Covenant delineates the unique role that Abraham’s seed will have in God’s plan for

the world and paves the way for Israel’s prominent role in that plan.

10

The Mosaic Covenant

This covenant follows the format of a suzerain-vassal treaty and represents

the constitution for the nation of Israel that grew out of Abraham’s descendants, a

development envisioned by the Abrahamic Covenant. In this covenant, God offered

cursing for disobedience and blessing for obedience. God’s basic demand was that

Israel would love Him exclusively (Deut 6:4-5).

236 The Master’s Seminary Journal

11

Various historians contend that David did not move the ark of the covenant to Jerusalem until the

latter part of his reign (e.g., Eugene H. Merrill, Kingdom of Priests [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1987] 243,

245-46; Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., A History of Israel: From the Bronze Age through the Jewish Wars

[Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1998] 246-48). Chapters 6 and 7 are located at this place in 2 Samuel

for thematic rather than chronological reasons. It appears that the event of 2 Samuel 6–7 did not take

place until after David completed his building projects in Jerusalem (w ith Hiram’s assistance, 1 Chr 15:1)

and after his many military campaigns (2 Sam 7:1).

12

Paul House, Old Testament Theology (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1998) 241.

13

The Lord softens the impact of this announcement on David by using the title “servant” to

demonstrate that although David’s plan is rejected, David himself is not. Also, rather than using a blunt

negative statement, the Lord addresses David in the form of a question (cf. Gordon, I & II Samuel 237).

14

Cf. R. A. Carlson, David, the Chosen King (Uppsala, Sweden: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1964) 114-

28.

15

Although some scholars contend that the provisions in 7:8-11a were not fulfilled in David’s

lifetime (e.g., Robert D. Bergen, 1, 2 Samuel [Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1996] 339), at the very

least they found initial fulfillment during David’s lifetime. David’s reputation was established, Israel

occupied the land of promise, and Israel had no major contenders for power in their part of the Near East.

This initial fulfillment does not mean that the prophets could not look forward to the presence of these

same provisions in future settings (cf. Isa 9:7; 16:5; Jer 23:5-6; 33:15-16).

THE OLD TESTAMENT ARTICULATION

OF THE DAVIDIC COVENANT

2 Sam 7:8-16 (cf. 1 Chr 17:7-14)

Background Issues

Historical Preparation. David’s transportation of the ark to the city of

Jerusalem made that city the center of Israelite worship (2 Sam 6:1-23). With the

entire nation under his control, with the government centralized in Jerusalem, and

with no external foes at that time (7:1),

11

David expressed his desire to build a

structure to house the ark of the covenant (7:2).

12

Nathan initially encouraged David

to proceed with his plans to build the Temple (7:4-7). However, that night Yahweh

told Nathan to inform David that a descendant of David would build this Temple.

13

The Lord had other plans for David. As the God who orchestrated David’s meteoric

rise to power and prominence, Yahweh related His plan to establish David’s lineage

as the ruling line over God’s chosen people (7:8-16).

The term “covenant” (;*9EvA , brît). Although the Hebrew term for

“covenant,” ;*9EvA (brît), does not occur in 2 Samuel 7, the biblical expositions of

the passage (cf. 2 Sam 23:5; Pss 89:35; 132:12) make clear that it provides the initial

delineation of the Davidic Covenant. In his covenant with David, Yahweh presents

David with two categories of promises:

14

those that find realization during David’s

lifetime (2 Sam 7:8-11a)

15

and those that find fulfillment after his death (2 Sam

The Davidic Covenant 237

16

This break in the passage is indicated by at least two structural elements. The third person

affirmation in 7:11b, “Yahweh declares to you,” interrupts the first-person address in 7:8-11a and 7:12-

16. The timing of the anticipated fulfillment of the promises made in 7:12-16 is found in the phrase,

“When your days are over and you rest with your fathers” (7:12a).

17

The standard translations evidence a debate among scholars over the perspective of this issue of

making David’s name great. The KJV and NKJV render it as a past reality (“have made your name

great”) while a number of translations (NASB, NIV, NRSV) translate it as a future promise (“will make

your name great”). Although certain scholars contend that the form (*;E EI3A&) represents a copulative or

connective vav on the perfect verb and carries a past nuance (A. Anderson, 2 Samuel [Dallas: Word,

1989] 110, 112, 120; O. Loretz, “The Perfectum Copulativum in 2 Sm 7,9-11,” CBQ 23 [1961]:294-96),

most scholars posit that the form entails a vav consecutive (also called correlative) on the perfect verb and

sho uld be translated with a future sense in this case (A. Gelston, “A Note on II Samuel, 7:10,” ZAW 84

[1972]:93; R. P. Gordon, 1 & 2 Samuel (Sheffield: JSOT, 1984) 74-75; P. K. McCarter, Jr., II Samuel

[New York: Doubleday, 1984] 202-3). Although the shift from past to future that occurs at the midpoint

of verse nine is not clearly demarcated, the fact that three other perfect verbs prefixed with a conjunction

and then two imperfects (preceded by the negative particle) suggest that a future nuance fits all these

verbs. The verb in question (*;E EI3A& ) occurs after a break in verse nine (after the athnach) and probably

looks back to the imperfect verb that begins this section (“thus you will say,” v. 8). The intervening

material provides the foundation for the promise that Nathan introduces in verse 9b.

18

Deuteronomy 11:24 affirms that “every place” where the Israelites set their feet will be theirs. Cf.

Carlson, David, the Chosen King 116.

19

In this appointed place Israel will not move any more and will not be oppressed by the sons of

wickedness (2 Sam 7:10). This place will be Israel’s own place as well. The “plant” imagery also

suggests permanence (cf. Exod 15:17; Pss 44:2; 80:8; Isa 5:2; Jer 2:21; Amos 9:15).

7:11b-16).

16

Promises that find realization during David’s lifetime (7:9-11a)

A Great Name ( v. 9; cf. 8:13). As He had promised Abraham (Gen 12:2),

the Lord promises to make David’s name great (2 Sam 7:9).

17

In Abraham’s day,

God’s making Abraham’s name great stood in clear contrast to the self-glorifying

boasts of the builders of the tower of Babel (Gen 11:4). The same is true in David’s

day. Although David’s accomplishments as king cause his reputation to grow (2

Sam 8:13), Yahweh was the driving force in making David’s name great. He is the

One who orchestrated David’s transition from being a common shepherd to serving

as the king over Israel (2 Sam 7:8).

A Place for the People (v. 10). The establishment of the Davidic Empire

relieved a major concern involved in God’s providing a “place” for Israel (7:9). The

land controlled by Israel during David’s reign approached the ideal boundaries of the

promised land initially mentioned in conjunction with God’s covenant with Abram

(Gen 15:18).

18

Consequently, during David’s reign the two provisions of the

Abrahamic Covenant that deal with people and land find initial fulfillment. In

addition to this and more closely tied to the immediate context,

19

the “place” that

Yahweh will appoint for Israel probably highlights the idea of permanence and

238 The Master’s Seminary Journal

20

D. F. M urray, “MQWM and the Future of Israel in 2 Samuel VII 10,” Vetus Testamentum 40

(1990):318-19; cf. Bergen, 1, 2 Samuel 339 n. 67. Murray (“MQWM and the Future of Israel” 319)

argues that the locative aspect of .&8/ is subsidiary to the qualitative aspect. He concludes, “2 Sam vii

10, then, acknowledges that Israel’s occupation of the land, long since a physical reality, has been beset

by many hazards. It affirms, however, that through David (and his dynasty) Yahweh will transform that

place of hazard into a place of safety, into a permanent haven of security for his people” (“MQWM and

the Future of Israel” 319).

21

The same debate over whether the verb here signifies a past occurrence or a future promise seen

in verse 9b also occurs here. For the reasons detailed above, the future sense is accepted.

22

R. P. Gordon, 1 & 2 Samuel 74.

23

Carlson, David, the Chosen King 102.

24

W. J. Dumbrell, “The Davidic Covenant,” Reformed Theological Review 39 (1980):40.

25

Ibid.

26

Ibid., 45.

security.

20

Rest (v. 11). David’s “rest” from his enemies mentioned in 7:1 sets the

historical and conceptual stage for the promise of rest in verse eleven. Though the

absence of ongoing hostilities provided the window of opportunity for David to

move the ark to Jerusalem and consider building a Temple for Yahweh, that “rest”

only foreshadowed the “rest” to which Yahweh refers.

21

Even after all of David’s

accomplishments, level of security and prosperity was yet unattained by the

kingdom, a rest that is still future.

22

The noun “rest” (%(I {1/A , mnuhE â) “is intimately

associated with the land”

23

and accompanies the expulsion of those who lived in the

land (i.e., the Canaanites). The Lord also contrasts this enduring rest He promises

David with the temporary rest provided by the various judges (who periodically

delivered Israel from oppression at the hands of the “sons of wickedness”; 7:10b-

11a).

Promises that find realization after David’s death (7:11b-16)

A House (v. 11). Dumbrell

24

suggests that 2 Samuel 6 provides the

theological preparation for chapter seven. The divinely approved movement of the

ark to the city of Jerusalem represents God’s choice of Jerusalem as the future site

for the Temple, i.e., a “house” for the ark of the covenant. The presence of God,

which rests on the ark of the covenant, will serve as a tangible reminder of Yahweh’s

kingship over Israel. Next, chapter seven focuses attention on the erection of

another “house,” i.e., the dynasty of David and, consequently, the perpetuation of

his line. This juxtaposition of these chapters suggests that the king had to provide

for the kingship of Yahweh before the question of Israel’s kingship is taken up.

25

It

also implies that the Davidic kingship was ultimately to reflect the kingship of

God.

26

In 2 Samuel 7 Yahweh had to first establish the “house” of David before

The Davidic Covenant 239

27

After the introductory expression, “thus says the Lord,” the question is introduced by an

interrogative he prefixed to the second person pronoun: “You, will you build for me a house to dwell

in?”.

28

Kaiser’s delineation of the Davidic Covenant (Walter C. Kaiser, Jr., Toward an Old Testament

Theology [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1978] 150) occasioned this observation.

29

TLOT, s.v. “;*E Hv,” by E. Jenni, 1:235; cf. TDOT, s.v. “;*E Hv,” by Harry A. Hoffner, 2 (1975):114.

30

Athaliah had sought to exterminate the “whole seed of kingship,” i.e., David’s dynasty (2 Chr

22:10).

He would permit the building of a “house” of worship by David’s son, Solomon. In

verse five, Yahweh asks, “Are you the one who should build Me a house to dwell

in?”

27

In verses twelve and thirteen Yahweh introduces the “descendant” of David

and affirms that “he will build a house [i.e., the Temple] for My name,” placing the

personal pronoun in the emphatic position. After describing the rest He would give

David during his reign (v. 11), Yahweh affirms His intention to build David’s

“house.” Not only does Yahweh seek to have the ark of the covenant moved to

Jerusalem to demonstrate tangibly the presence of His dominion in Jerusalem, but

He also attends to the eternal “house” of David before He speaks of the erection of

a structure to house Israel’s worship of Himself. The building of the “house”/Tem-

ple by mankind could only occur after Yahweh “built” the “house” of David.

28

Although the Hebrew term ;*EHv (bayit) refers to a fixed house built of any

material in most instances, its meaning can shift to the contents of the house and

particularly to the household living in the house.

29

In this usage it can refer to a

family or clan of related individuals (e.g., Noah’s family, Gen 7:1), lineage or

descendants (e.g., the house/line of Levi, Exod 2:1), or, in reference to kings, a royal

court or dynasty (the house/dynasty of David, 2 Sam 7:11; Isa 7:2, 13). The term

occurs seven times as part of Yahweh’s promise to David (7:11, 16, 19, 25, 26, 27,

29). At least two contextual indicators demonstrate that bayit refers to David’s

dynasty rather than his immediate family or even his lineage. The juxtaposition of

“house” with “kingdom” suggests that it deals with a royal dynastic line (7:16) and

the presence of “forever” with reference to this “house” in three verses (7:16, 25, 29)

and mention of “distant future” in another verse (7:19) suggests a duration that

exceeds most family lineages.

A Seed (v. 12). Although this term 39HG' (zera‘), “seed” can signify a

collective meaning of posterity (Gen 3:15; 12:7; 13:15), it occurs only once in 2

Samuel 7 and refers to Solomon, to all the royal descendants of David, and

ultimately to the Messiah, Jesus Christ. Solomon would be the guarantee for the rest

of David’s descendants and would erect the Temple (7:13). Yahweh also guarantees

that Davidic descendant would always be available to sit on the royal throne.

30

Yahweh states that He will set up or raise up (.{8, qûm) this seed.

A Kingdom (v. 13). Various passages in the Pentateuch anticipated that

240 The Master’s Seminary Journal

31

Bergen, 1, 2 Samuel 340. Notice how this reality appears in the NT writers’ application of 2 Sam

7:13 to Jesus (see below).

32

Weinfeld, “Covenant of Grant” 185.

33

Ibid.

34

Waltke, “Phenomenon of Conditionality” 124.

35

Weinfeld, “Covenant of Grant in the Old Testament” 185.

36

Waltke, “Phenomenon of Conditionality” 124

Israel would one day have a king (Gen 17:6, 16; 35:11; Deut 17:14-20) and

constitute a kingdom (Num 24:7, 19). However, this kingdom which God promises

to establish through David does not replace the theocracy. It is regarded as God’s

throne/kingdom (1 Chr 28:5; 2 Chr 9:8; 13:8). In fact, the Davidic ruler is called

“the Lord’s anointed” (1 Sam 24:6; 2 Sam 19:21).

In verse 12 the Lord spoke of raising up the descendant or seed of David

and in verse 13 declared that this descendant would erect His “house” or Temple.

The reader immediately thinks of Solomon, David’s son and heir to the throne who

constructed the first glorious Temple in Jerusalem. Yahweh then affirms that

David’s dynasty (“house”) and throne/kingdom would be eternal (7:13 16). This

statement in verses 13 and 16 vaults this portion of God’s oath beyond the time

frame of Solomon’s reign (which ceased to exist immediately after his death). This

incongruity between divine prophecy and human history invited the NT writers to

await a different son of David who would rule eternally.

31

Conditionality/Unconditionality

Grants vs. Treaties

As with the other biblical covenants treated in this issue, the concepts of

conditionality and unconditionality are not mutually exclusive. An unconditional

covenant is not necessarily without conditions just as a conditional covenant can

have unconditional elements. Weinfeld’s proposal of the terms grant and treaty

clarifies the differences between the biblical covenants.

32

In a grant the giver/maker

of the covenant offers the promise or commitment. The grant constitutes an

obligation of the master to his servant and protects the rights of the servant

primarily.

33

The grant may be called unconditional “in the sense that no demands

are made on the superior party.”

34

In a treaty the giver/maker of the covenant

imposes an obligation upon someone else. A treaty represents the obligation of the

vassal or servant to the master and primarily protects the rights of the master.

35

A

treaty is conditional in the sense that the master promises to reward or punish the

vassal for obeying or disobeying the covenant stipulations.

36

As with other “grant”-style covenants, in establishing this covenant with

David Yahweh places no obligations on David as it relates to the enactment or

The Davidic Covenant 241

37

Ibid.

38

Ibid., 131.

39

Weinfeld, “Covenant of Grant in the Old Testament” 190; cf. Avraham Gileadi, “The Davidic

Covenant: A Theological Basis for Corporate Protection,” Israel’s Apostasy and Restoration: Essays in

Honor of Roland K. Harrison, ed. A. Gileadi [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988] 158. In the second

millennium, adoption served as the only way to legitimize the bestowal of land and rulership.

40

Weinfeld (“Covenant of Grant in the Old Testament” 191) refers to a treaty between Šupilluliumaš

and Mattiwaza which illustrates this practice of adoption/sonship: “(The great king) grasped me with his

hand . . . and said: ‘When I will conquer the land of Mittanni I shall not reject you, I shall make you my

son [using an Akkadian expression for adopting a son], I will stand by (to help in war) and will make you

sit on the throne of your father.’”

41

Robert B. Chisholm, Jr., “A Theology of the Psalms,” A Biblical Theology of the Old Testament,

ed. Roy B. Zuck (Chicago: Moody, 1991) 267.

42

Weinfeld (“Covenant of Grant in the Old Testament” 189) cites a treaty between the Hittite king

Hattušiliš III and Ulmi-Tešup of Dattaša to illustrate this point: “After you, your son and grandson will

possess it, nobody will take it away from them. If one of your descendants sins the king will prosecute

him at his court. Then when he is found guilty . . . if he deserves death he will die. But nobody will take

away from the descendant of Ulmi-Tešup either his house or his land in order to give it to a descendant

of somebody else” [emphasis in the original].

perpetuation of the covenant.

37

In that sense the Davidic Covenant is unilateral and,

consequently, unconditional. Any conditions attached to this covenant concern only

the question of which king or kings will enjoy certain provisions laid out by the

covenant.

Contextual Indicators of Conditionality and Unconditionality

The writer of 2 Samuel brings together the irrevocable and conditional

elements of Yahweh’s grant to David by means of the imagery of sonship

38

in 7:14-

16:

I will be his father and he will be my son. When he does wrong, I will punish him with

the rod of men, with floggings inflicted by men. But my love will never be taken away

from him, as I took it away from Saul, whom I removed from before you. Your house

and your kingdom will endure forever before me; your throne will be established forever

(NIV).

The clause “I will be His father and he will be My son” serves as an

adoption formula and represents the judicial basis for this divine grant of an eternal

dynasty (cf. Pss 2:7-8; 89:20-29).

39

The background for the sonship imagery (and

the form of the Davidic Covenant, see above) is the ancient Near Eastern covenant

of grant, “whereby a king would reward a faithful servant by elevating him to the

position of ‘sonship’

40

and granting him special gifts, usually related to land and

dynasty.”

41

Unlike the suzerain-vassal treaty (e.g., the Mosaic Covenant), a

covenant of grant was a unilateral grant that could not be taken away from the

recipient.

42

242 The Master’s Seminary Journal

43

Gileadi, “The Davidic Covenant” 159. Cf. Waltke, “Phenomenon of Conditionality” 131.

44

Although Gileadi (“The Davidic Covenant” 160) suggests Yahweh’s presence in Zion constitutes

the sign or token of the Davidic Covenant, Waltke (“Phenomenon of Conditionality” 131) suggests that

the absence of a sign might be intentional since anything in addition to the promised son or sons would

be superfluous.

45

A number of scholars argue that the term “forever” in 2 Samuel 7 and “everlasting” in the

expression “everlasting covenant” in other passages only refers to the span of a human life (e.g.,

Matitiahu Tsevat, “Studies in the Book of Samuel (Chapter III),” Hebrew Union College Annual 34

[1963]:76-77) and does not signify the idea of “non-breakability” (Marten Woudstra, “The Everlasting

Covenant in Ezekiel 16:59-63,” Calvin Theological Journal 6 [1971]:32-34). Tsevat (“Studies in the

Book of Samuel” 77-80) and others (e.g., Woudstra, “Everlasting Covenant” 31-32) also contend that the

unconditional elements in 2 Samuel 7 were glosses added to the passage (which was originally

exclusively conditional) at a later time.

It is as Yahweh’s son that David and his descendants will enjoy the

provisions of this covenant. These verses also introduce the possibility that disloyal

sons could forfeit the opportunity to enjoy the provisions of this covenant (cf. 1 Kgs

2:4; 8:25; 6:12-13; 9:4, 6-7; Pss 89:29-32; 132:12). As with Abraham (Gen 12:1-3),

Yahweh promised David an eternal progeny and possession of land. Loyal sons, i.e.,

those who lived in accordance with the stipulations of the Mosaic Covenant, would

fully enjoy the provisions offered them. However, disloyal sons, i.e., Davidic

descendants who practice covenant treachery, will forfeit the promised divine

protection and will eventually lose their enjoyment of rulership and land. Even

though Yahweh promises to cause disloyal sons to forfeit their opportunity to enjoy

the provisions of this covenant, He affirms that the Davidic house and throne will

endure forever, giving the hope that Yahweh would one day raise up a loyal son who

would satisfy Yahweh’s demands for covenant conformity.

43

Although the line of

David may be chastised, the terms of this covenant, the Ehesed ($2G G() of God, will

never be withdrawn.

David himself had no doubts concerning the ultimate fulfillment of this

divine grant. Although 2 Samuel 7 and the related passages do not refer to any

external sign or token, David regards these promises as certain when he declares,

“For the sake of your word and according to your will, you have done this great

thing and made it known to your servant” (2 Sam 7:21).

44

In 2 Sam 7:13b, the Lord

stresses that “I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever.”

45

In his last words,

David affirms, “Truly is not my house so with God? For He has made an everlasting

covenant with me, ordered in all things, and secured; For all my salvation and all my

desire, will He not indeed make it grow?” (2 Sam 23:5).

In addition to various references in the historical books to the everlasting

nature of this covenant, the prophet Jeremiah records how the Lord vividly affirmed

His unwavering intention to bring the Davidic Covenant to fulfillment. The Lord

compares the certainty of the Davidic Covenant to the fixed cycle of day and night

(Jer 33:19-21). He hypothetically proposes that if God’s covenant with day and

night would lapse, i.e., if one could somehow alter the established pattern of day and

The Davidic Covenant 243

46

F. B. Huey, Jr., Jeremiah, Lamentations (Nashville: Broadman, 1993) 302.

47

David Noel Freedman, “Divine Commitment and Human Obligation,” Interpretation 18

(1964):426. In addition to this account in 2 Samuel, Psalms 89 (vv. 4-5, 29-30, 35, et al.) and 132 (vv.

11-12) present these two sides of the issue.

48

Gileadi, “The Davidic Covenant” 159.

49

Kaiser, Toward an Old Testament Theology 157. Various Hittite and Neo-Assyrian treaties also

protected the unconditional provision of a given covenant against any subsequent sins committed by the

original recipient’s descendants (cf. Weinfeld, “Covenant of Grant in the Old Testament” 189-96).

Concerning the conditional element in Exod 19:5, Weinfeld affirms that this “condition” is “in fact a

promise and not a threat. . . . The observance of loyalty in this passage is not a condition for the

fulfillment of God’s grace . . . but a prerequisite for high and extraordinary status” (ibid., 195).

50

The same juxtaposition of covenant and immoral activity occurs in Genesis 9 with regard to the

Noahic covenant and Noah’s drunkenness.

51

Waltke, “Phenomenon of Conditionality” 131.

night (Gen 1:5; 8:22), then God’s covenants with David (2 Sam 7) and the Levites

(Exod 32:27-29; Num 25:10-13) could also be broken. As Huey points out, “The

hypothetical (but impossible) termination of day and night is an emphatic way of

stating that those covenants cannot be broken.”

46

Like the other unilateral biblical covenants or grants (Abrahamic, New ), the

Davidic Covenant demonstrates a balance between the potential historical

contingencies and the ultimate theological certainty.

47

On one hand, the conditional

elements or historical contingencies could affect whether or not the nation and its

Davidic leader enjoy the provisions offered by the covenant made with David. On

the other hand, the unconditional elements leave open “the possibility of YHWH’s

appointment of a loyal Davidic monarch in the event of a disloyal monarch’s default.

YHWH’s protection of his people, by virtue of the Davidic Covenant, could thus be

restored at any time.”

48

As Kaiser points out, The “breaking” or conditionality of the

Abrahamic/Davidic Covenant “can only refer to personal and individual invalidation

of the benefits of the covenant, but it cannot affect the transmission of the promise

to the lineal descendants.”

49

That David’s sin with Bathsheba (2 Sam 11–12) closely follows the

presentation of the Davidic Covenant is contextually significant in showing the

unconditionality of the covenant.

50

Also, King Solomon’s covenant treachery that

led to the dissolution of the Davidic empire did not represent the failure of the

Davidic Covenant. As Waltke points out, this arrangement of the biblical text

demonstrates that “the beneficiaries’ darkest crimes do not annul the covenants of

divine commitment.”

51

Royal Psalms

Scholars have categorized a number of psalms under the heading of “royal

psalms” because they share a common motif—the king. These psalms (Psalms 2,

244 The Master’s Seminary Journal

52

Kaiser, Toward an Old Testament Theology 159.

53

Chisholm, “A Theology of the Psalms” 268.

54

Kaiser, “The Blessing of David” 301-3, provides a helpful treatment of the differences between

presentations of the Davidic Covenant in 2 Samuel 7 and Psalm 89.

18, 20, 21, 45, 72, 89, 101, 110, 144) draw heavily on the idea of a Davidic dynasty

and presuppose the covenant God established with David. They focus on a Davidic

figure who, as Yahweh’s son, lived in Zion, ruled over God’s people, and was heir

to the divine promise.

52

As examples of this psalmic genre, two of the royal psalms

receive consideration (Pss 72, 89).

Psalm 72

By personal example and deed, the Davidic king was to promote

righteousness and justice in the land (v. 1). He would do this by defending the cause

of the afflicted, weak, and helpless and by crushing their oppressors (vv. 2, 4, 12-

14). The ideal Davidic ruler would occasion the national experience of peace,

prosperity, and international recognition (cf. vv. 3, 5-11, 15-17).

53

God promised to

give His anointed king dominion over the entire earth (vv. 8-11). Although this

psalm may have been written at the beginning of Solomon’s reign, it envisions ideals

never fully realized in Israel’s history. Only during the millennial reign of Christ

will the peace and prosperity depicted by this psalm find fulfillment.

Psalm 89

54

In concert with the initial expression of the Davidic Covenant in 2 Samuel

7, the psalmist affirms that the Davidic king enjoyed the status of God’s “firstborn”

(vv. 26-27). God promised His chosen king a continuing dynasty (v. 4), victory over

his enemies (vv. 21-23), and dominion over the whole earth (v. 25). If a Davidic

ruler failed to obey God’s Word he would be severely disciplined and forfeit full

participation in the benefits of the covenant (vv. 30-32). However, even in the wake

of disobedience the Lord would not revoke His promise to the house of David (vv.

33-34). God’s lovingkindness to David, i.e., the Davidic Covenant, will endure

“forever” (vv. 28, 29, 36, 37). The psalmist affirms that God’s promise to David

was as certain as the constantly occurring day/night cycle (v. 29; cf. Jer 33:19-21)

and as reliable as the continuing existence of the sun and moon, which never fail to

make their appearances in the sky (vv. 35-37).

This psalm depicts the psalmist seeking to resolve his belief in God’s oath

to David and the reality of his day, divine judgment for covenant treachery. After

reminding God of his promised to David’s house (vv. 1-37), he lamented the fate

experienced by the Davidic dynasty in his lifetime (vv. 38-51). Yahweh had “cast

off and abhorred” his anointed ruler (v. 38) and had “profaned his crown” (v. 39).

The Lord had given victory to the king’s enemies (vv. 40-44) and had covered him

with shame (v. 45). The psalmist cries out, “How long . . . will your wrath burn like

The Davidic Covenant 245

55

Kaiser (“The Blessing of David” 307) calls the complex of OT covenants “the Abrahamic-

Davidic-New Covenant.”

56

Ibid., 308.

57

Besides a few changes and additions, most of the following information comes from Kaiser, “The

Blessing of David” 309.

fire,” and “Where are Your former lovingkindnesses, which you swore to David?”

(vv. 46, 49).

The psalmist’s frustration demonstrates at least two truths. First of all, at

this point in Israel’s history, the ideal of a just king who would bring the nation

lasting peace and prosperity was still an unfulfilled ideal. Secondly, the inability of

Davidic rulers to live and rule in accordance with God’s demands causes the reader

to look forward for a Davidic figure who would one day perfectly satisfy those

divine expectations.

THE COHERENCE OF THE OLD TESTAMENT COVENANTS

Every student of the Bible must realize that the various biblical covenants

revealed in the OT are interconnected. One must not keep the promises they contain

separate from each other as mutually exclusive sets of covenant provisions (like

distinct post office boxes). Rather, throughout the OT God is weaving a beautiful

covenant tapestry, weaving each new covenant into the fabric of the former

covenants.

55

Although the Davidic Covenant does introduce something new to the

covenantal package, Kaiser is correct when he affirms, “What God promised to

David was not a brand new, unrelated theme.”

56

The recognition of continuity or sameness and discontinuity or differences

in God’s revelation of the biblical covenants must accompany belief in progressive

revelation. As God reveals His will for mankind and Israel in particular, He repeats

certain features already presented and introduces other brand-new elements.

Students of God’s Word must take great care not to ignore either side of that coin.

The following section emphasizes the points of connection between the biblical

covenants to help visualize the forest as well as the trees. The coherence of these

covenants does not signify sameness. Although each covenant addresses distinct

issues in God’s plan for His creation, they do not operate in a mutually exclusive

fashion.

Thematic Connections with the Preceding Covenants

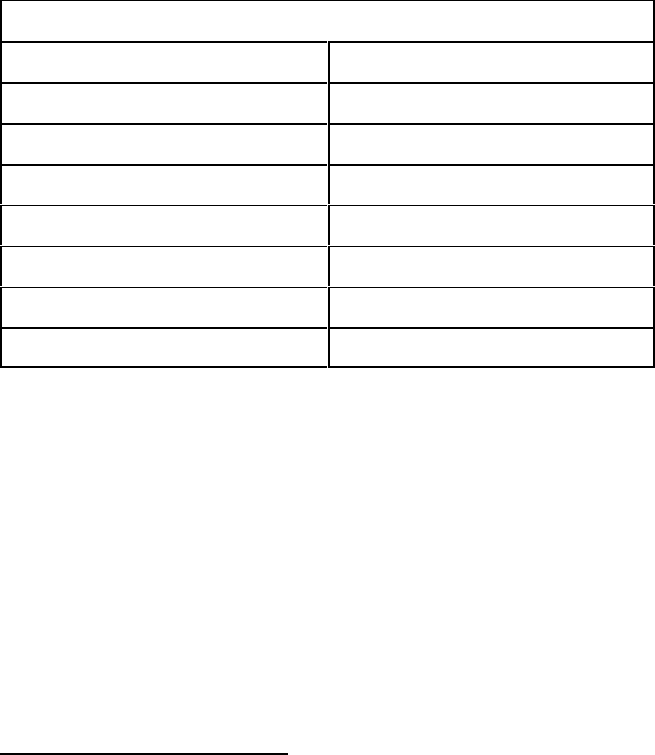

Several themes in 2 Samuel 7 mirror similar statements in the various

articulations of the Abrahamic and Mosaic covenants (see Figure #2).

57

246 The Master’s Seminary Journal

58

The title ’|dÇn~y YHWH (%&%* *1IK$!C) only occurs five other times in biblical books that cover

biblical history between Genesis 15 and 2 Samuel 7 (Deut 3:24; 9:26; Josh 7:7; Judg 6:22; 16:28). The

non-compound title “’|dÇ n ~y” (*1IK$!C, “Lord”), exclusive of the occurrences of ’|dÇnî (*1EK$!C), “my lord,”

and ’|dÇnê (*1FK$!C), the lord of,” occurs only seven other times in historical literature (Josh 7:8; Judg 6:15;

1 Kgs 3:10, 15; 22:6; 2 Kgs 7:6; 19:23).

Figure #2: Thematic Parallels between the Davidic Covenant

and Preceding Scripture Passages

Theme

Statement

Specific Phrase 2 Sam 7

Passage

Similar Statements in

Preceding Scriptures

International

Reputation

“I will make you a

great name”

7:9b Gen 12:2

Land

Inheritance

“I will also appoint

a place for my peo-

ple”

7:10a Gen 12:7; 13:15; 15:18;

Deut 11:24-25; Josh

1:4-5

Descendants “I will raise up your

descendants after

you”

7:12b Gen 13:16; 15:5; 16:10;

17:7-10, 19

Sonship “I will be a father to

him and he will be

a son to me”

7:14a Exod 4:22-23

Intimate

Relationship

“My people” 7:7-8,

10-11

Gen 17:7-8; 28:21;

Exod 7:7; 29:45; Lev

11:45; 22:33; 5:38;

26:12, 44-45; Num

15:41; Deut 4:20;

29:12-13

David’s prayer of thanksgiving to God after the Lord established His

covenant with David offers another connection with the Abrahamic Covenant. In

six verses (7:18, 19 [2x], 20, 22, 28, 29) David uses the compound divine title “’AdÇnaî

YHWH” (%&%* *1IK$!C ) to address the Lord. This title does not occur elsewhere in 1

and 2 Samuel and occurs only twice in 1 Kings (2:26; 8:53).

58

The passage in 1

Chronicles 17 that parallels 2 Samuel 7 uses “YHWH ’lÇhîm” (.*%E K-!B %&%*, 17:16,

17), “’lÇhîm” (.*%E K-!B , 17:17), and “YHWH” (%&%*, 17:19, 20, 26, 27) instead of

the title originally used by David (see Figure #3). The special significance of

David’s use of this title derives from the fact that Abraham used the same title when

The Davidic Covenant 247

59

Kaiser, “The Blessing of David” 310.

60

Alva J. McClain, The Greatness of the Kingdom (Winona Lake, Ind.: BMH, 1974) 156. M cClain

refers to the provisions of the Abrahamic Covenant as “regal terms” because of their connection with the

Mediatorial Kingdom.

addressing the Lord in Genesis 15 (vv. 2, 8) as the Lord was reaffirming His

intention to make Abraham’s seed abundantly numerous. Based on this correlation,

Kaiser argues that David’s use of this compound name for God indicated that he

“was fully cognizant of the fact that he was participating in both the progress and

organic unity of revelation. The ‘blessing’ of Abraham is continued in this

‘blessing’ of David.”

59

Figure #3: Parallel Titles in 2 Samuel 7 and 1 Chronicles 17

2 Samuel 7 1 Chronicles 17

7:18–%&%* *1IK$!C (’|dÇn~y YHWH) 17:16–.*%E K-!B %&%* (’lÇhîm YHWH)

7:19–%&%* *1IK$!C (’|dÇn~y YHWH) 17:17–.*%E K-!B (’lÇhîm)

7:19–%&%* *1IK$!C (’|d Çn~y YHWH) 17:17–.*%E K-!B %&%* (’lÇhîm YHWH)

7:20–%&%* *1IK$!C (’|dÇn~y YHWH) 17:19–%&%* (YHWH)

7:22–%&%* *1IK$!C (’|dÇn~y YHWH) 17:20–%&%* (YHWH)

7:28–%&%* *1IK$!C (’|dÇn~y YHWH) 17:26–%&%* (YHWH)

7:29–%&%* *1IK$!C (’|dÇn~y YHWH) 17:26–%&%* (YHWH)

Connections between the Abrahamic and Davidic Covenants

As seen in the above thematic parallels, the Abrahamic and Davidic

covenants share the motifs of international reputation, land inheritance, and

descendants. McClain suggests that the Davidic Covenant “consisted of a

reaffirmation of the regal terms of the original Abrahamic Covenant; with the further

provision th at these covenanted rights will now attach permanently to the historic

house and succession of David; and also that by God’s grace these rights, even if

historically interrupted for a season, will at last in a future kingdom be restored to

the nation in perpetuity with no further possibility of interruption.”

60

Merrill points

out that the Davidic Covenant is theologically rooted in the Abrahamic Covenant

rather than the Mosaic Covenant. He contends that

there are important connections and correspondences between the Abrahamic and

248 The Master’s Seminary Journal

61

Merrill, Kingdom of Priests 185.

62

David M. Howard, Jr., “The Case for Kingship in Deuteronomy and the Former Prophets,” WTJ

52 (1990):114. Levenson (“The Davidic Covenant” 207-15) delineates two common ways that scholars

have explained the relationship between the Mosaic and Davidic covenants. The “integrationists” view

the Davidic Covenant as an outgrowth of the Sinaitic Covenant, overlooking the differences with regard

to conditionality and unconditionality (ibid., 207-9). The “segregationists” identify some kind of tension

or even antimony between these two covenants, often suggesting points of tension without scriptural

support (ibid., 210-15). Although Levenson’s overview is helpful, his solution is not compelling. He

suggests that scholars can only understand the relationship between these two covenants by recognizing

the plurality of theological stances that co-existed in Israel (ibid., 219).

63

Dumbrell, “The Davidic Covenant” 46

Davidic covenants. This is most apparent in Ruth itself. The narrator is writing, among

other reasons, to clarify that the Davidic dynasty did not spring out of the conditional

Mosaic covenant, but rather finds its historical and theological roots in the promises to

the patriarchs. Israel as the servant people of Yahweh might rise and fall, be blessed or

cursed, but the Davidic dynasty would remain intact forever because God had pledged

to produce through Abraham a line of kings that would find its historical locus in Israel,

but would have ramifications extending far beyond Israel.

61

The writer of the first gospel, Matthew, introduces his genealogy of Jesus

Christ by pointing out that the Messiah is both the son of David and the son of

Abraham (Matt 1:1).

Connections between the Mosaic and Davidic Covenants

Most comparisons of the Mosaic and Davidic covenants focus on the

conditional/unconditional issue.

62

The Mosaic Covenant is obligatory, bilateral, and

conditional. The Davidic Covenant is promissory, unilateral, and ultimately

unconditional. The Mosaic Covenant is like a treaty while the Davidic Covenant is

comparable to a grant. Under the Mosaic Covenant, the failure by the Israelites to

live in conformity to the covenant stipulations can occasion covenant curse and the

loss of covenant favor, including tenure in the land of promise. However, according

to the Davidic Covenant, the treacherous conduct of any one or series of Davidic

rulers does not hazard the ultimate realization of its provisions.

The Psalms, however, suggest a point of connection between these two

covenants. The royal psalms depict the king as conducting his rule in accordance

with the stipulations of the Mosaic Covenant. Dumbrell concludes, “Davidic

kingship is thus to reflect in the person of the occupant of the throne of Israel and as

representative of the nation as a whole, the values which the Sinai covenant had

required of the nation.”

63

The reigns of Hezekiah, Manasseh, and Josiah (2 Kgs 18-23) provide a

The Davidic Covenant 249

64

Gerald Gerbrandt (Kingship according to the Deuteronomistic History [Atlanta: Scholars, 1986]

45-102) provides a helpful study of 2 Kings 18–23 regarding the relationship of the king’s function to

the stipulations of the M osaic Covenant.

65

Howard, “Case for Kingship in Deuteronomy” 102.

66

Gerbra ndt, Kingship according to the Deuteronomistic History 102.

67

Erich Sauer (The Triumph of the Crucified [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1951] 92) states, “In its

essence this new covenant is the fulfilment of two Old Testament covenants, that with Abraham and that

with David.”

68

Here is a listing of some of those material blessings with relevant Scripture references: regathering

of Israelites (Jer 32:37-40; Ezek 36:24, 28, 33; 37:21), repossession of the land of promise (Jer 24:6;

31:28; 32:41; Amos 9:15), taming of the animal kingdom (Ezek 34:25-27; cf. Isa 11:6-9), agricultural

prosperity (Ezek 34:25-27; 36:30, 34-36; Amos 9:13), cessation of war and the reign of peace (Jer 30:10;

Ezek 34:28; 36:6, 15; 39:26), reuniting of Israel in one kingdom (Jer 50:4; Ezek 34:23; 37:22), Israel

ruled by one king (Ezek 34:23; 37:22, 24), a sanctuary rebuilt in Jerusalem (Ezek 37:26-27a).

vivid demonstration of the relationship of the Mosaic and Davidic covenants.

64

The

stipulations of the Mosaic Covenant provide the “measuring stick” for the reign of

each of these kings (2 Kgs 18:6; 21:7-9; 23:24-25). The function of the God-fearing

king was to lead Israel in keeping covenant and in relying on God for deliverance.

65

As Gerbrandt points out, the king “was to lead Israel by being the covenant

administrator; then he could trust Yahweh to deliver. At the heart of this covenant

was Israel’s obligation to be totally loyal to Yahweh.”

66

The proper role of the

Davidic king was to lead his people in keeping Torah. Herein lies an important

convergence between the Mosaic and Davidic covenants. The Davidic ruler should

epitomize the standards of the Mosaic Covenant, even though his conformity or lack

of conformity to those standards does not determine whether or not Yahweh will one

day bring to realization the provisions of the Davidic Covenant.

Connections between the Davidic and New Covenants

The connections between these two covenants are limited in scope since the

Davidic Covenant focuses on regal issues and the New Covenant concerns

redemptive issues. An important touchstone is the fact that the perfect descendant

of David also functions as the mediator of the New Covenant. More broadly, the

New Covenant appears to be the covenant that brings to fruition all the preceding

covenants.

67

In addition to the locus classicus for the New Covenant (Jer 31:31-34),

other statements or allusions to the New Covenant include more tangible blessings

(possession of the promised land, regathering of Jews, one kingdom ruled by one

king centered in Jerusalem, etc.)

68

along with the intangible spiritual blessings

conveyed by the New Covenant.

Summary

The provisions of the Davidic Covenant represent part of the plan God has

250 The Master’s Seminary Journal

for His creation. As God set forth the various biblical covenants, each one

represented a step forward in the revelation of God’s intentions for the world.

Rather than operating in distinct orbits or realms, each covenant builds on the

preceding covenant or covenants. Each covenant introduces new elements to God’s

revelation of His plan and those elements become part of the multi-faceted tapestry

of biblical covenants.

CONCLUSION

As part of God’s revelation of His plan for His chosen people, the Davidic

Covenant has both immediate and far-reaching implications. In addition to

establishing David’s dynasty, this covenant looks forward to a descendant of David

who would bring peace and justice to God’s people through his reign. The

conditions that accompany this covenant only determine who will function in this

capacity, not whether or not a Davidite will rule in this way.