lD: I started out in Little League when I was seven years old.

You were supposed to be eight to get in the League, but I was

at the forefront of the Baby Boomer generation, and we moved

into some track home neighborhoods in the suburbs of Los

Angeles, and the fathers were all excited and energetic, coming

back from the war….They built a big complex of elds and held

tryouts at a public park, and I went down there with my dad just

to watch because it said you had to be eight years old. But then,

it turned out that they needed a couple more kids to ll out all

the teams, and so I got in one year early. And then, I continued

through Little League, Pony League, Colt League, high school,

American Legion, and was generally one of the better players

throughout that whole time. By the time I got in high school, it

was evident that I could throw pretty hard and so I started get-

ting scouted. There were twenty teams back then and I ended up

lling out some sort of a questionnaire and sending it in for the

ofce for seventeen of them, not the Dodgers. That was the team

I followed. They were not interested. But when it came down to

it, it was the Twins, the Cubs, and the Colt .45s. . . . I signed out

of high school, got a pretty big bonus, and a college scholarship

where they would pay me $1,000 a semester.

So I started my career when I was seventeen in an instruc-

tional league and went to school during the off seasons. I came

up [to Houston] in September that very rst year, pitching three

games for the Colt .45s. The rst one was on my eighteenth

birthday. I pitched against Willie Mays, and he hit one foul off

me about 450 feet. And then, I ended up striking him out. So,

that was kind of a career bullet point. I never went back down.

I was so excited about playing baseball in the major leagues

that . . . I did not notice that Houston was so hot or that the

mosquitoes were so big, they could carry you off and all the

things that people said about old Colt stadium . . . I went back

to California to go to college the rst couple of off-seasons and

at that time, I thought, well, this will be a great place to have a

baseball career. The Astrodome was fabulous. I was happy with

Houston but I sort of thought that in the end, I would end up in

California. But the longer I stayed here, the more friends we

made and the deeper our roots grew.

[The opening of the Astrodome the next year] was terric.

I can remember at the end of spring training, we came back

here, and we played those exhibition games with the Yankees.

And when we came up to the Dome, it was dark outside and

the lights were on inside. So, when we got off the team bus,

we walked into the Astrodome, went in the locker room, and

walked out and looked at the stadium. And walking out through

the tunnel and looking at the expanse of the eld and score-

board, it was breathtaking. I can even remember at the time say-

ing I felt like I walked into the next century. It was almost like it

had a ying saucer quality to it or something, futuristic.

A Conversation with...

MR. ASTRO, LARRY DIERKER

and Joe Pratt

L

arry Dierker has been associated with the Houston

Astros baseball franchise since 1964, when he pitched

his first game at old Colt .45 Stadium. He pitched thirteen

seasons for the Astros and one with the St. Louis Cardi-

nals before he retired from baseball in 1977. He finished

with 139 wins and a 3.31 earned run average. In 1979

he became a color commentator, broadcasting Astros

games until 1997, when he left the booth and returned

to the bench as the team’s manager. For five seasons he

was the most successful manager in Astros’ history, tak-

ing four of his five teams to the playoffs and leading the

team to 102 wins in 1999.

In November of 2007, we met at his home in Jersey Vil-

lage and talked about his career with the Astros, baseball,

and Houston.

Larry Dierker began his career in an instructional league and

pitched in his first major league game for the Houston Colt .45s on his

eighteenth birthday.

All photos courtesy of Houston Astros, unless otherwise noted.

4 Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports

The expansive interior of the Astrodome, as it appeared before the

gondola was raised to the roof, “had a flying saucer quality to it.”

The Astros played their first exhibition game against the New York

Yankees on April 9, 1965.

.

It was really hard to hit a home run [in the Dome]. The only

thing that was somewhat helpful to the hitters was the original

version of Astroturf was a really fast track. So, the inelders did

not have quite as much range as they had in other ballparks, and

the balls that were hit into the gaps or down the lines generally

made it to the fence. And so, it was probably a better than aver-

age park for doubles and triples, but certainly way below the

average park for home runs. I think, at rst, it was just intrigu-

ing, and I think the inelders kind of liked it because they did

not get any bad hops. But then, you know, after a while, you

know, with diving for balls and slamming down on it and get-

ting abrasions and hitting down hard and everything, after a few

years, players did not really like the Astroturf that much. The

original Astroturf in the Dome did not have any padding under

it . . . just concrete.

JP: Do you think that

pitching in the majors at

such an early age helps

explain your relatively

early retirement?

lD: I think it [starting

so young in the majors]

was probably not the

best thing for me, in

retrospect, because I was

nished when I was thir-

ty-one. I had arm trouble

for three or four years

leading up to that. But,

philosophically, I am not

opposed to pushing a

Larry Dierker at spring training in

1965.

Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports 5

young player, you know, to try to maybe chal-

lenge him to perform at a higher level than he

might be ready for, just to see what will happen.

There are two schools of thought on that. Some

people feel like the young prospect should move

up one step at a time and that you should not put

them into an overwhelming situation because

they might lose their condence. My feeling has

been that if you put them into that kind of a situ-

ation and they fail, they will probably learn why

they failed and then they will go back down. If

they are the kind of competitor that you want,

they will go back down there and work on that

and x it and come back up again. And if they

are somebody that once defeated, they are going

to be defeated forever, they are probably not the

person you want anyway.

The trend has been to take longer and longer

[to bring pitchers to the majors]. What happened

with me is not going to happen again. [I was] a

starting pitcher’s manager—if you are a starting

pitcher that likes to get the decision. What I would tell them is

when you go out there to start the game, you want the decision

— win or loss. If you are afraid to lose, you know, you are going

to always be one to bail out of a tied game in the fth or sixth

inning; that way, you cannot lose. The proper mental attitude is

to go for the win even at the expense of a possible loss and pitch

as far into the game as you can so you do not need as much help

from the bullpen. And mostly guys responded well to that. We

were on a four-man rotation and pitching lots of complete games

[when I was coaching the Astros]. We used to pitch the whole

season on the fourth day.

I did not know that much about pitching when I signed [as a

rookie]. I signed because I could throw the ball hard, and I could

throw it over the plate. And I had a pretty good breaking ball.

But I did not really have the best idea of what to do with that.

The process of learning how to pitch was expedited by pitching

in more games and more innings and being coached by profes-

sionals…. Once I signed, the process really moved forward

quickly, especially, you know, having to try to compete in the

major leagues. I could not only see what was happening to me

when I was on the mound and talked to the catcher about it and

the pitching coach or the manager. But I could also watch what

Juan Marichal was doing, or what Warren Spahn was doing, and

Don Drysdale, or Bob Gibson. I mean, you are right there where

you can watch and see the best pitchers doing it, you know, and

that really helped me learn what to do, too. So, it was a com-

bination of pitching more innings and watching better pitchers

and getting better coaching.

Jim Owens was a team mate. He pitched the rst year or

two that I played. He was on the staff, then he became pitching

coach. And I probably learned most of the early lessons from

him. And after him, the guy that was really good was Roger

Craig. He came through as pitching coach for two or three years

here during the middle of my career…. It is sort of an interest-

ing dynamic because when young guys come up, they obviously

take another guy’s place. And so, a lot of times, the guy’s place

you take might be a popular guy among the other pitchers and

they might be a little disgruntled at rst but everybody knows

that that is the nature of the sport. So, after the

guy is gone and you are there for a while, then

you are on the team trying to help and they start

trying to help you.

One of the things that really helped me was

there was not much pressure because we knew

we were not a contending team….It was no

pressure, you are in the major leagues, getting

rst class treatment, riding around in chartered

planes, having people give you money for your

meals and stuff. It was glamorous to me. By

today’s standards, it would be minor league, but

for me at that time and that age, I was thrilled.

Every I time I went back to college, I started

after the baseball season, so I was usually two

weeks to a month late coming into classes. I

could catch up just ne in classes like English or

history or anything where you read a book and

then you have to write about what you read, but

when it came to things that were more technical,

I was in trouble. About my third or fourth year,

I thought I should major in business because I had some money,

and I thought that would be a prudent thing to do. But when I

came back to calculus and accounting and computer science one

month late, I was lost. Within a couple of weeks, I dropped all

those classes, and I ended up with political science and econom-

ics. And the next year, I switched over to majoring in English.

One thing that helped me a lot — we got Johnny Edwards

over from the Cardinals and he was a good catcher. In 1969 (at

the age of twenty-two) in spring training, I actually went 5-0,

and he was just adamant that if I was going to pitch in the major

leagues, I needed to learn how to

throw pitches other than my fast ball

behind [in] the count 3-2. I worked

on that a lot in spring training, and

I found that I could get the ball over

the plate, or if I did not, they would

swing at it if it was out of the strike

zone because they were all look-

ing for fast balls. And that was one

of the last pieces in the puzzle—

you know, of putting together all

the things I had to offer on the

mound—to have enough condence

to do those sorts of things. And he

was instrumental in that.

I feel like you could imagine how

I would feel, or how any twenty-

two-year-old would feel, in that

position. I think I was pretty full

of myself, you know. It was a good

feeling. I knew I was one of the best

and I knew it was not an accident.

I was happy about it, and I was

a big shot. I knew I was going to

make a bunch more money. I think

everybody has to work that out for

themselves because one thing that

I felt several times is when I was in

As a young player who had just

joined the majors, Larry Dierker

enjoyed the first class treatment,

which he said would be “minor

league” by today’s standards.

6 Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports

my prime and my arm was healthy, and I was warming up for a

game, and I felt good, and we were playing a weak team, and I

would look over and they would have a lesser pitcher warming

up to pitch against me, and I thought we are going to win this

game. This is going to be fun. And I asked Nolan [Ryan] if he

ever felt that way one time. He said, “Not once.” His attitude,

it was going to be a war no matter what the team was with the

opposing pitcher, and he was never going to let up. Of course, he

won more than twice as many games than I did, so he probably

had a better philosophy.

JP: You make the All-Star team in 1969 and 1971. Did you pitch

in the 1969 game?

lD: Yes, I pitched in that game in Washington. I only faced two

hitters. There were two outs in the inning. Boog Powell got a

single, Reggie Smith popped up and that was it. In 1971, I was

hurt. I was really off to the best start I had ever been. I was

10-1, I think at one point, and my ERA was below 2. My elbow

was burning every start. But I was having so much success

that I was just putting hot stuff on it and going out there. It got

worse in the game at Candlestick Park, my last start before the

All-Star game, to the point where I had to go on the disabled

list. Don Wilson took my place, and he pitched an inning in that

game in Detroit. I was there, and I was chosen for the team, but

I did not pitch. . . .

I think the tendency now is to just shut a guy down until it

gets to where it does not hurt. . . . I think they are a little more

cautious now than they used to be. It used to be, you know, just

get a cortisone shot, put hot stuff on it, take pain killers, and go

out there and pitch.

In 1970, my arm was ne but that was 300 innings in 1969

and 270 more in 1970. [In] 1971, when I made

the All-Star team, my elbow bothered me mid-

season, and I missed the whole second half of that

season. And the next year, my shoulder started

giving me some trouble. I got over the elbow

problem and it probably changed my delivery or

something a little bit to protect my elbow. I am

not sure what happened but the next year, it was

the beginning of the shoulder. I was not too hurt

for a few years there — I just had occasional

shoulder discomfort, but the last two or three

years were basically not knowing from one start

to the next if I was going to be able to go out there

and make my next start.

What tests they did, they never really diag-

nosed anything. I think if I had been pitching in a

later era, in this era, there is no way that I would

have retired at thirty-one. Somebody would have

said, “You have got to get that shoulder xed

and keep pitching,” because it is too hard to nd

good pitchers and, you know, when a guy is that

young, it is obvious the rest of your body is ne,

so I think they would have found a way to x

my shoulder. But back then, if they did not have

something they knew they had to operate on, they

did not operate, and they could not nd anything

they knew they had to operate on.

Dierker, shown here in 1975, continued to be an effective pitcher de-

spite battling shoulder and elbow problems.

Larry Dierker received an award for pitching his first no-hitter in a

game on July 9, 1976, against the Montreal Expos.

Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports 7

JP: Despite your sore arm, late in your career, you pitched a no

hitter.

lD: I just went into that game thinking I was going to mix it up

and move it around like I had been and by the seventh inning,

I got the adrenaline, and I did not know my arm was sore any-

more. Actually, I had lost two no-hitters on ineld hits late in

the game, one in the ninth inning. We were in the Dome and the

last two innings, I decided I was not going to give up a ground

ball that might be a hit. It was either going to be a y ball or a

strikeout. I think I struck out four guys in the last two innings,

and I was basically just throwing high fast balls. I did not throw

anything but fast balls the last two innings and here I was, going

into the game with my arm a little fragile thinking I am just

going to not overdo it, just mix it up and move it around. It was

almost like two games: the rst part of the game pitching and

the last couple of innings just throwing. It was like old times.

In 1969, we were close in the beginning of September, and

then we caved in, much like the 1996 team did, which led to me

getting the manager’s job — being close and then falling out in

the end. I think that all of us would have liked to have had a shot

at playing when it really counts at the end of September and the

pennant race and in the post season. I think there was a realiza-

tion during most of those years in the 1970s that we just were

not as talented as the Dodgers and Reds. They were great teams.

At some point, you just have to look at the other team and say,

“they’ve got more talent than we do.”

I think we felt that we possibly could have won the eastern

division a couple of those years but it was just like playing in

the American League East now; you know, Toronto may have a

great team, but they are not going to beat Boston or New York.

There were some good trades. We got Jose Cruz for Claude

Osteen. I am not sure if there was anything quite that good until

Bagwell came along but that was certainly a good deal. But,

you know, the Morgan deal and the Cuellar deal really hurt, and

the Rusty Staub deal, too. So, we lost a lot of

talent. Paul Richards was the general manager

until the judge [Roy Hofheinz] prevailed in the

ownership situation with R. E. “Bob” Smith.

The judge did not like Paul so he let him go

and then hired Spec Richardson, and he made

most of the dumb deals. But I do not think

Paul Richards would have made those trades,

and I think we probably would have been an

even better team in the late 1960s and early

1970s if we had not made those deals. And,

to me, it was really a dening moment for the

franchise because my understanding is that the

judge and Bob Smith were not getting along,

seeing eye-to-eye, and Bob Smith gave him

a buyout price and a date, and he thought he

probably would not be able to come up with

the money, but the judge was such a charmer

and such a dreamer and an eloquent speaker

and everything else, that he did manage to

scrape up the money, and he bought Bob

Smith out. And had Bob Smith become the

sole owner instead of Roy Hofheinz, I think

that the franchise would have been better.

We might not have had the Astrodome. I mean, the judge was

certainly a major gure in Houston history and an innovator in

terms of the Dome. And obviously, that has led to other domes

and retractable roof stadiums. He was probably a genius. I think

he was one of the youngest mayors any major city has ever had.

But from the baseball standpoint and player personnel, I think

we would have been better off with Bob Smith because I think

he would have kept Paul Richards and let Paul do the baseball

work, whereas, I think the judge got Spec in there and started

trying to be part of it and I think that was a mistake.

JP: How did the players react to what turned out to be a series

of bad trades in these years?

lD: There is not anything you [as a player] can do about it, and

even when we made that trade with Cincinnati [Joe Morgan

trade], I thought it was an O.K. trade. Tommy Helms was a good

second baseman, so we still had a good second baseman. We

had power with Lee May and Jimmy Stewart was a switch hit-

ting, utility type player. I did not think it was going to turn out

to be such a horrible trade.

If he [Joe Morgan had] stayed here, he probably would not

have achieved what he did achieve…. because, you know, if you

are a pitcher and you have good elders behind you and good

hitters in your lineup, you are going to have a better record than

if you are pitching for a lesser team. And if you are a hitter and

you have good hitters in front of you and good hitters behind

you, you are going to have better numbers than if you are hitting

on a team where you do not have good other hitters around you.

So, it helped him to be in that lineup, but he would have been a

great player no matter what. He had that intensity of focus and

spirit for competition that was off the charts, as most of the Hall

of Fame guys do.

Craig Biggio will be the rst to be a lifetime Astro to make

it [into the Hall of Fame], and I think Jeff Bagwell will make

it, too. Sentimentally, I hope that Bagwell makes it on the third

ballot so he will go in at the same time that Biggio does. And

Astros owners R. E. “Bob” Smith and Judge Roy Hofheinz.

8 Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports

that could happen, you know, because his career was shortened.

And so, even though his numbers are extraordinary, the total

RBIs and total runs scored are a little low because he does not

have as many at bats because of his injury, but his averages —

on base, slugging, RBIs per year, runs scored per year—are all

better than many rst basemen who are already in there and I

think that the voters will realize that.

JP: When were you rst aware of the possibility of steroid use?

lD: I do not think that I picked up on that before it started be-

coming news. You know, once you read about it or heard some-

body, a commentator speak about it, and then you looked around

at some of the guys. I thought about the guys I played with.

You know, when I was playing, there weren’t many guys lifting

weights, so it was possible just to assume that we all would have

looked like that if we had lifted weights because we did not.

I think the effect of it is really overblown because just for one

particular reason, that certainly guys hit more home runs, there

was a higher quantity of home runs, but in terms of distance

of the long home runs, you would think that if the steroids was

making a guy that much stronger, that he would hit the ball that

much farther. But there were balls that Frank Howard hit and

balls that Willie Stargell hit and balls that Mickey Mantle hit in

different stadiums, and these guys in this era who have played

in those same stadiums, nobody has hit the ball any farther. And

we know those guys were not taking any steroids. So, you know,

I think it maybe has had an effect but I think that because of

the quantity of home runs, which I think is partially due to poor

pitching depth, that it is assumed that cheating is so bad that

anybody could do it if you took steroids, anybody could pitch a

no-hitter through spit balls or scufng the ball. I think there is a

suspicion among fans that all these things that have happened in

the game would be categorized as cheating, have a major effect

on the game, and I think they probably have a more subtle effect

on the game, and it is really not the impact—and this is just my

opinion—I think these things have not had the impact that the

fans think they have.

If you have guys like Sosa and McGwire and Bonds who

were already established stars, it is hard to understand why they

would succumb to that temptation, but if you look at a guy that

is twenty-eight years old who is in AAA making $50,000, and

major league minimum is $325,000, he has got a wife and a

couple of kids, he has been in the minor leagues for ve years

and he is thinking if I could just get a little better and get a

couple of years in the big leagues, at least I would have a start

on my next life. I can understand that.

At one of our alumni events a couple of years ago, it was the

1980 team. It was before anybody knew about steroids, and guys

were sitting around having a beer, and somebody said, “Well, if

I was playing now, I would take steroids. I would not want to go

against all those guys if we’re not going to be on the same play-

ing eld.” And just about every single guy said the same thing,

you know. If everyone else is doing it, I would do it.

We will never know [who took steroids and who did not] and

the other thing is what we do know, I think, is that when you are

in your twenties, you do not care what effect it will have on you

when you are sixty. I mean, the people were saying, “You are

going to pay the price for this down the line with your health.”

When you are young, you are invulnerable, you know, I mean,

the last thing you are thinking about is how you are going to feel

when you are sixty.

They [Major League Basesball] probably could have started

[testing] sooner than they did. I think in baseball, they were

probably pleased with the Sosa/McGuire thing, and probably

attendance was going up, and they may have been dragging

their feet almost semi-intentionally because the game was very

popular, and there were a lot of home runs; and it was almost

like when Babe Ruth started hitting them and other guys started

hitting them, and the game became popular that the people that

owned the teams and run the game were thinking, well, let’s

don’t rock the boat. Things are going pretty good. And so, it

kind of leaked out and became known, and they almost got to

the point where they had to do something. And now, they have

nally done something. But they still have a problem with the

human growth hormones. They need a blood test, I guess. I

think you can get that with a blood test.

There was a Hall of Fame player that said baseball must be

the greatest game on earth to survive the fools that run it. Can

you imagine when that was said? It was said in 1941 by Bill

Terry. So, you know, you could say at this point in time that the

players and the union run it, just as easily as you could say the

owners run it. But the statement is still basically true. We have

come through strikes, and we have come through steroids, and

we have come through World War II, and we have come through

drug trials in Pittsburgh in the early 1980s, and it seems like the

game is able to survive all sorts of scandals and unseemly be-

havior. And now with the steroids, if a bunch of guys are impli-

cated in January, and they say, “But we’ve got this stuff cleaned

up now,” I think all it is going to do is make it more popular.

JP: How hard was your transition from being a player to being

an announcer?

lD: It was not that hard. I think that when you do something

like that, you do not really know how to do it, but your knowl-

edge of the game can make the presentation reasonably infor-

mative even if you are not a professional broadcaster, and then

after a few years, you become a professional broadcaster. It

takes everybody a couple of years to learn the timing of things.

It is especially difcult on TV. I mean, it is a nightmare on TV

right now because they throw so many charts and graphs up

there, special effects and sponsored elements, that you can-

not really tell a story anymore. You cannot speak more than a

couple of sentences because they are liable to put something up

there on the screen, and you have to stop and talk about what

is on the screen. And so, it makes it difcult to be anecdotal

and to present the game the way I like to have it presented, in

a friendly and informative way, because it just seems like they

want that People Magazine ash, ash, ash, cut, ash, cut,

cut, cut — that they are trying to make the game seem like it is

really fast moving and exciting when it is really just baseball. It

is a pastime. And I prefer it as a pastime. On radio, you can still

broadcast it that way but on TV, you cannot.

I was pretty lucky to grow up in L.A. and hear Vince Scully

“When you are young, you are invulnerable

...the last thing you are thinking about is how

you are going to feel when you are sixty.”

Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports 9

all the time. And then, I spent my last year with St. Louis and I

heard Jack Buck quite a bit because I was damaged goods when

I went, and I only pitched thirty some innings for them, and

I did not go on all the trips because I was on the disabled list.

So, I got to hear Jack Buck a lot. I think those two guys were

probably, in terms of just baseball announcers, the best that the

National League had to offer.

I worked with Dewayne Staats and Gene Elston about the

rst half and then Milo Hamilton and Bill Brown the second

half, roughly. I probably had a little closer relationship with the

players when I rst started announcing because I was just in

my thirties. I was the same age as a lot of the players, and I had

played with or against them. And so, it was almost like I was

still a player, but then as I grew older and the players got young-

er, and there was nobody that I had played against or with, you

know, then I had a separate relationship, which was more just

a professional thing, you know — talked to them, interviewed

them, say hello on the bus or around the batting cage but not go

out and have a beer or go play golf or anything. It separated as I

got older.

I got to get in the race as an announcer and then I got to

get in the race as a manager. I was never in it as a player. That

Philadelphia series [in 1980] was probably more exciting than

the Mets series [in 1986]. I got to do both of those. I had Nolan’s

4,000

th

strikeout. I was doing play-by-play on radio at that time.

[While announcing] I did a lot more statistical analysis, and

I read more books from people like Bill James and others that

kind of broke the game down analytically in ways that I had not

thought about before. So by the time I went down to manage, I

think I had a better idea of what creates runs scored, more than

the elding. The pitching was something I knew from experi-

ence, and I knew from experience that the better elders you

have, the better pitcher you are going to be. So, that was the

prevent-runs standpoint and that was mostly from experience.

But the offensive part was less familiar to me—slugging aver-

age, on base average, the percentage of

steals and what percentage you have to

do to gain an advantage, and the number

of the percentage of games where the big

inning wins the game. And then, I went

through my scorebook to see if that was

true; so I went through a whole year,

and about 50% of the time, you know,

the winning team scored more in one

inning. Even if it was a 2-1 game, they

scored the two runs in one inning. And

then, I took it a step farther and said,

well, how many times does a team score

as many runs in one inning as the other

team does in a whole game, and it was

70%. So, when I went down to manage,

I was armed with those ideas, and a lot

of managers are not. You know, a lot

of managers still think about the team

that scores rst wins 60% or 70% of

the time. But, you know, the team that

scores rst could score ve runs in the

rst inning and still score more than the

other team does in the whole game. So,

both of those things could happen in the

same game. But a lot of managers bunt and play little ball in the

early part of the game to try to get the rst run because they have

heard that the team that scores rst wins. I never did that when

I managed. I tried to play for the big inning until the end of the

game when we only needed one run.

Managing the game was fun, but managing the situation was

not fun. It was probably the job that I least enjoyed of all the

things I have done in baseball, just because of the combination

of having to get there so early because the players get there so

early and have nothing to do until the game starts except talk to

the media. And then, the media kind of pressure in the season

where we had a bad year and even in the seasons where we lost

in the playoffs. By the time it was over at rst, you know, it [be-

ing removed as manager] kind of hurt my feelings because we

had won the division that year; but after about one month, I felt

like I had had a big burden taken off of me, and I realized that I

could be a lot happier person if I did not have to be responsible

for what happened out on the eld. But actual tactics, from the

rst pitch to the last pitch, I enjoyed that.

I had great players. Oh, I mean, that is critical. You can screw

up a good team if you make everybody mad and you are a bad

manager, but you cannot possibly take a team of middling talent

and win a championship through the shrewdness of your tactics.

I probably emphasized defense, pitching, and elding more

than most managers for that reason. I think in the Big Bang era,

most managers, coming from playing positions rather than from

pitching, they think a little more about how are we going to

outscore the other team, and I would probably think how are we

going to allow fewer runs than the other team? And I probably

was less reluctant to go into extra innings to shoot for the moon,

change pitchers in the fth inning to try to have a big inning. I

was kind of a save-your-ammunition type manager, not really

reacting too much to what was going on early in the game un-

less you just absolutely had to. But if it was a close game, even

if we were a little behind, I would say, “Let’s save our best pinch

The Astros made the playoffs four of the five seasons Dierker managed the team, and he was elected

Manager of the Year in 1998.

10 Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports

hitter. Let’s save our right and left pinch hitter. Let’s save this

relief pitcher. Let’s let this pitcher pitch another inning,” and just

kind of let the game go a little further before I started trying to

use my reserves in my bullpen.

[In the play offs,] it was three times the Braves and one time

the Padres. And in all of those series, we faced some sensational

pitching. I mean, not only were these guys good pitchers during

the year but, I mean, we caught Kevin Millwood when he struck

out fteen guys. You just could not hit him that day. It was

probably the best his arm ever felt in his whole career. And his

control was great too! Kevin Brown had a similar game against

us. And, of course, Maddox and Glavine and Smoltz. I felt like

there were times during the year that we could have scored runs

off those guys throwing the way they did. But most of the time

you don’t hit guys who are throwing that well. . . . we just could

not get past that rst round, mostly because we could not score.

1998: That was the Kevin Brown year, and that was when

we had our best team and won 102 games. That was the year I

thought we had the best talent in the league, and the Padres beat

us. I think [Randy Johnson] was 10-1. He was good in that rst

game against Kevin Brown, too. We lost 2-1, I think, but we

only scored a run in the ninth off Trevor Hoffman because they

took Kevin Brown out. But I think he pitched eight innings and

struck out fteen guys in that game. Guys were just walking

back to the dugout going . . . what are you supposed to do?

In 1999, we won again — I thought that I did a better job that

year, and that was the year I had the seizure. So, I missed about

one month of that season. But that year, we won 97 games. And

we were decimated by injuries. I had Biggio and Spiers in the

outeld during most of September. We lost Moises Alou for

the whole year and Richard Hidalgo for about half of the year,

and had other injuries as well. Plus, the Reds were just putting

relentless pressure. . . . At one point, we won eleven or twelve

games in a row and we only picked up one game on them.

It got down to the very last day of the year, and we won

[against the Dodgers] in the Dome, and it was the last regular

season game in the history of the Dome, and the confetti, and

the Astros team of honor, and the champagne, and Harleys, and

cigars. There were players from different generations, and ev-

erybody was going around hugging each other and everything.

It was a really special time, that particular part of it, and that

was only a part of it. To me, it was one of the most memorable

days of my whole career and we had to win that game to win

the division. So, I felt like, you know, 97 games in that year was

probably more difcult to obtain than the 102 the year before.

And then, in 2000, the rst year at Minute Maid, we had a

lousy year, 70-92. The pitchers freaked out. Bagwell and all

those guys were not hitting until the second half. It was just an

inexplicable bad year for a team that had quite a bit of talent.

And then the next year, we won again and lost in the playoffs to

the Braves.

I thought [Minute Maid Park] was great. I mean, I was

concerned about the home run and the effect it was having on

the mentality of the pitching staff but I thought it was a beauti-

ful park. I was ready to leave the Dome. I loved the Dome, but

when they took the scoreboard down and put up more seats, it

just looked like any other multipurpose stadium . . . the Dome

just seemed passé at that point, and I was ready for a new one

[ballpark]. And then, when I saw the new one, I loved it, and I

still love it.

JP: You were fortunate to have a chance to play in some of the

great old ballparks in your early years in the big leagues.

Larry Dierker was honored in a ceremony naming the All-Astrodome team at the final regular season game played at the Astrodome on

October 3, 1999.

Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports 11

lD: Yes, I did. Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, Crosley Field,

Forbes Field, Connie Mack Stadium, County Stadium — all of

them.

JP: And then watched them all get replaced by multipurpose

stadiums.

lD: Well, the Dome was . . . we kind of led everybody down the

primrose path because they thought, boy, isn’t this great? You

can have one stadium — football and baseball, put down Astro-

turf and you do not have to take care of the grass. I mean, this is

the way of the future. Everybody followed and now, they have

all said, “This is a terrible idea. It is not ideal for baseball or

football. We need separate stadiums. The Astroturf is no good.”

But all that started because of the Astrodome.

The thing about baseball that is so charming is that, you

know, people collect ball parks….Thomas Boswell once said

— their sounds, their sights, their smells, their neighborhoods

— they are unique and people go around and want to see a

game in every park, or people will go around if they are golfers

and they will want to play the great golf courses because every

golf course is different. . . . And, to me, those two sports are

unique for that reason, and I think really that for that reason, a

great deal of the best sports writing has been golf writing and

baseball writing.

When I got here, we had a very high percentage of Cardinals

fans because the Houston Buffs were here, and all the players

that came through Houston and went to St. Louis, among them,

Dizzie Dean and others, Joe Medwick and others, so people

liked the Cardinals. And a lot of people watched the Yankees on

the game of the week. And they were always on, and Hous-

ton did not have a major league team, so a lot of them became

Yankee fans or Cardinal fans. And then, over time, you know,

it seemed like the novelty of the Astrodome wore off and we

really did not have a very good core of baseball fans in Houston

at all. And then, when I rst got into broadcasting and take it

in the late 1970s, early 1980s, we had a combination of a lot of

things that were good for major league sports. We had a good

team. We were contending each year. The Oilers and Rockets

also did. And the oil business was booming, and we were able to

sell a lot of tickets and build a bigger core of baseball, football,

and basketball fans. And then, the teams, all of them sort of

faded. 1986 was a great team but it was just one team in the

middle of a fairly long run of not too good teams. But the last

ten or twelve years in baseball in Houston, with the combination

of the new ballpark and the contending teams year after year,

has built a core of baseball fans in Houston that I think is liable

to last. But in 2007, to be drawing 35,000 and 40,000 a crowd,

you know, all through the midweek in September when you are

already eliminated, you know, to me, that said this is becoming

a pretty good baseball town. . . . I think we are getting pretty

close to getting in that group of cities where people are going

to come and support the team no matter what the team does be-

cause they think, well, we may be down for a few years but we

will come back, because they have the expectation that we have

The Houston Astros take on the Cincinnati Reds at Minute Maid Park.

12 Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports

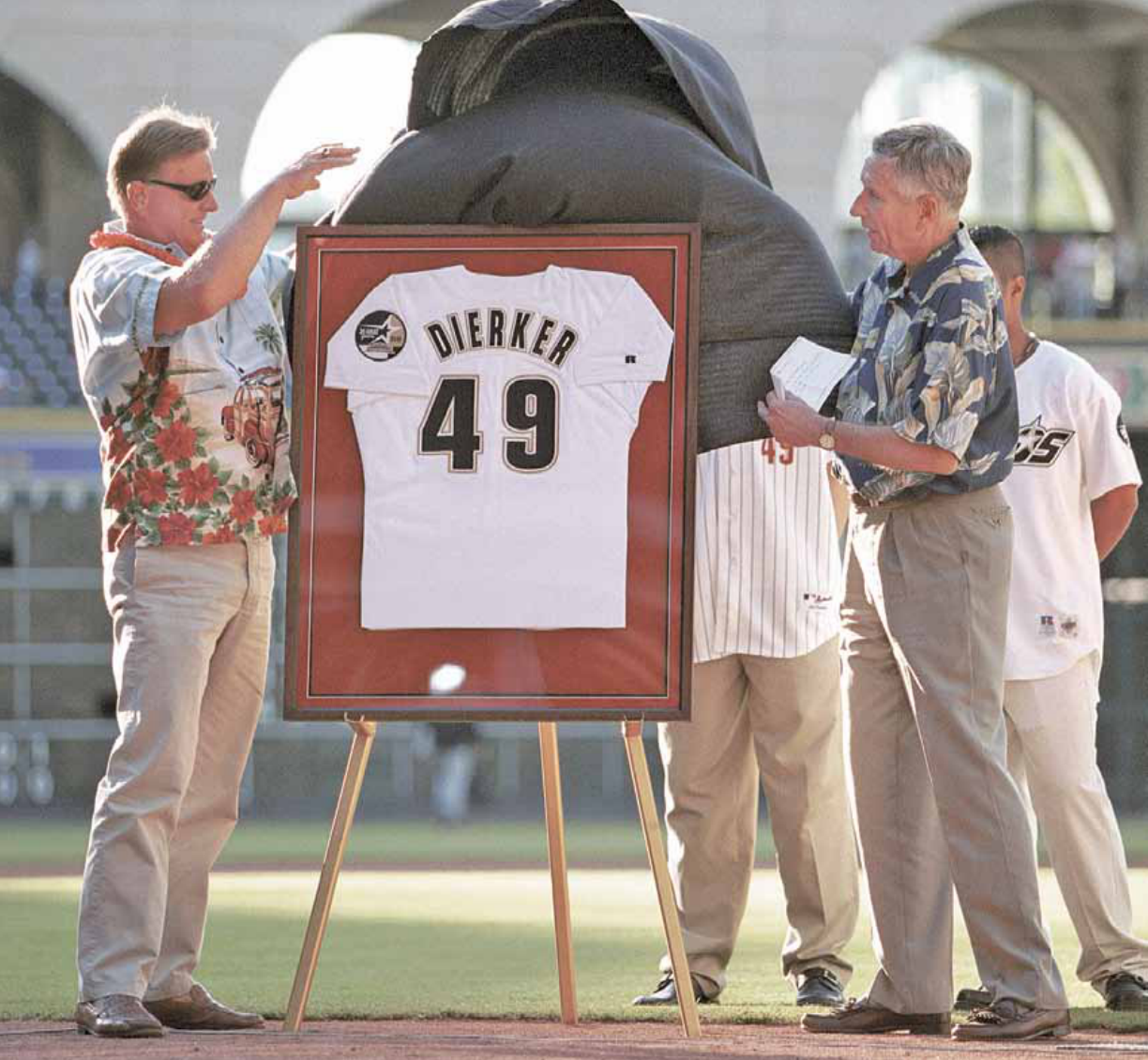

On May 19, 2002, Larry Dierker and Astros owner Drayton McLane, Jr. unveiled the framed jersey given to Dierker to commemorate the Astros

retiring his number 49.

done enough winning, been in the playoffs enough that I think

the mentality is that, well, we may be down now but we will get

back. . . . And I think that is the way Cardinal fans have always

felt. You know, their winning teams have come and gone. They

won a lot in the 1960s and 1980s but not in the 1970s. And they

have won a little bit lately but, you know, I think Cardinal fans

just say, well, we like the Cardinals — win or lose and we will

get our share of championships.

We have a good stadium, we have had a lot of success on the

eld, and we have a big city that is growing. And, you know,

even if you are new to Houston, if some guy comes to U of H,

and he is a new professor from somewhere else, and you become

friends, and you say, “Let’s go out to the ballgame,” you know,

we might have another fan! He might not need you to take him

the next time.

Joe Pratt is the editor of Houston History.

Vol. 6, No. 3–Sports 13