* The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be reported as or

attributed to the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or the governments of any of

its member countries.

Annual Meeting of Arab Ministers of Finance

April 2016

Manama, Bahrain

Economic Diversification in Oil-Exporting Arab

Countries

Prepared by Staff of the International Monetary Fund

I N T E R N A T I O N A L M O N E T A R Y F U N D

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY __________________________________________________________________________ 3

INTRODUCTION _________________________________________________________________________________ 6

BACKGROUND ___________________________________________________________________________________ 7

A. Stylized Facts About Oil-Exporting Arab Countries _____________________________________________ 7

B. The Case and Context for Economic Diversification ___________________________________________ 13

POLICY DISCUSSION __________________________________________________________________________ 18

A. Macroeconomic Pre-Conditions to Economic Diversification __________________________________ 18

B. Regulatory and Institutional Frameworks Conductive to Private Sector Growth _______________ 23

C. A Public Sector that Enables Private Sector Growth ___________________________________________ 27

D. The Road to a More Diverse Economy ________________________________________________________ 29

CONCLUSION __________________________________________________________________________________ 35

BOXES

1. Measuring Economic Diversification: Concepts and Indicators ________________________________ 11

2. Morocco: Diversifying Away from Phosphate and Agriculture _________________________________ 33

3. Pattern of Diversification of a Resources-Based Economy: Malaysia ___________________________ 34

FIGURES

1. Selected Indicators for Arab Oil Exporters ______________________________________________________ 8

2. Measures of Economic Diversity _______________________________________________________________ 10

3. Projected Impact of the Recent Drop in Oil Prices _____________________________________________ 16

4. Most Problematic Factors for Doing Business in Arab Oil Exporters ___________________________ 25

TABLES

1. Arab Oil Exporters: Key Sectoral Indicators _____________________________________________________ 9

2. Arab Oil Exporters: Selected Economic Indicators, 2014 _______________________________________ 13

APPENDIX

Technical Notes __________________________________________________________________________________ 37

REFERENCES ____________________________________________________________________________________ 39

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Despite their diversity in size, demographics and wealth, most oil-exporting Arab countries

face similar challenges to create jobs and foster more inclusive growth. The current

environment of likely durable low oil prices has exacerbated these challenges.

The non-oil private sector remains relatively small and, consequently, has been only a

limited source of growth and employment. While some countries have made more headway

than others in diversifying their economies, the energy sector, typically highly capital intensive,

remains dominant in many economies. However, it creates few jobs directly, while oil revenue is

often used to finance an oversized public sector. Still, the employment situation varies greatly

across countries: some GCC economies rely on foreign labor to fill private-sector jobs while

other Arab oil exporters need to meet the needs of a fast-growing domestic labor force.

Because oil is an exhaustible resource, new sectors need to be developed so they can take

over as the oil and gas industry dwindles. While some countries have ample reserves,

hydrocarbon resources in a number of Arab countries could be depleted in the foreseeable

future. However, even non-oil activities in many oil-exporting Arab countries are to some extent

dependent on funding from oil revenues. The challenge therefore is to grow truly self-sufficient

non-oil sectors that will provide a sustainable source of growth and employment even when oil

resources are depleted. Moreover, even countries with large proven reserves need to save a

larger share of their current oil income to promote greater intergenerational equity.

Over-reliance on oil also exacerbates macroeconomic volatility. When oil prices drop, as is

presently the case, the related decline in fiscal revenue often requires cuts in public spending,

which dampen growth in the non-oil sector and strain the sustainability of public employment.

Greater economic diversification would unlock job-creating growth, increase resilience to oil

price volatility and improve prospects for future generations. It would also broaden the base for

government revenue thereby reducing the reliance on oil and making the economy more resilient to

oil price shocks.

Macro-economic stability and supportive regulatory and institutional frameworks are key

prerequisites for economic diversification:

Insulating the economy from the impact of oil price volatility is necessary to lay a sound

foundation for economic diversification. It requires sound fiscal policy and framework,

effective liquidity management and prudent monetary policy, supportive financial sector policies

and a fairly valued exchange rate.

Strong regulatory and institutional frameworks are also needed to unlock private sector

potential. Improving the business environment, including streamlining procedures,

strengthening economic governance and transparency, and reducing regulatory barriers to

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

competition are needed for the private sector to grow. Labor market reforms and better access

to finance are also necessary.

The public sector should enable, not compete with, the private sector to support economic

diversification. Public employment and wage policies need to be tailored to improve incentives and

help raise the supply of highly-skilled labor for the private sector. Public spending needs to focus on

investment in infrastructure and human capital to improve competitiveness. Reducing excessive

monopoly rents in the nontradable sector by increasing competition and enhancing bidding

procurement processes would also help boost the private sector.

Policies and strategies to foster the emergence of dynamic new tradable sectors could

accelerate economic diversification. Economic diversification requires innovation in processes (to

enhance productivity), products (to sustain growth in new sectors), and organizations (to produce

more efficiently). Strategies could involve seeking to foster horizontal and vertical diversification,

diversifying manufacturing away from oil production, further integrating into the global value chain,

and attracting FDI into the non-oil sector.

The appropriate policy package and the sequencing of reforms need to be designed carefully,

taking into account each country’s specific circumstances and capacities. While the challenges

are similar, the diversity in size, demography, wealth, and economic structure of oil-exporting Arab

countries will warrant tailored responses. Specific recommendations will therefore vary across

countries.

It is acknowledged that economic diversification will not happen without security. Some

countries (Iraq, Libya, and Yemen) are affected by wars that severely disrupt economic activity and

weaken investor confidence. While this paper does not explicitly discuss this issue, it is understood

that restoring political stability and security is a necessary precondition to economic diversification.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

Key Recommendations to Economic Diversification

The table lays out the key policy recommendations to promote economic diversification in oil-exporting Arab

countries. Despite commonalities, these countries are diverse in size, demography, wealth and economic structure.

Therefore, the appropriate policy package and the sequencing of reforms need to be tailored to country

circumstances and capacities, drawing from the recommendations that are the most relevant to each case.

Macroeconomic Pre-Conditions to Economic Diversification

Develop a robust fiscal framework, based on a fiscal rule, to help achieve short and long-term objectives.

Ensure that the use of oil funds is governed by clear and transparent rules.

Improve liquidity management, including liquidity forecasting and the interbank market operations.

Develop strong regulatory, supervisory and macro-prudential frameworks to enhance resilience of the financial

sector to the volatility of oil prices.

Promote a fairly valued real effective exchange rate.

Regulatory and Institutional Framework Conductive to Private Sector Growth

Streamline government bureaucracy.

Reduce regulatory barriers to competition, including reviewing competition policy laws and their

implementation.

Promote greater trade integration

Review labor regulations to enhance labor market flexibility where needed (e.g., streamline regulations,

facilitate labor dispute resolution, and set incentives for higher women participation in the labor force) while

fostering better working conditions.

Reduce directed lending and develop domestic securities markets to increase access to finance.

Improve creditor assessment tools and infrastructure and creditor rights to enhance access to credit, especially

for small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

A Public Sector that Enables Private Sector Growth

Reduce the size of the public work force and the premium of public over private sector wages for comparably

qualified employees. Implement civil service review.

Increase public spending on education if it is low.

Enhance the quality of education, including orienting education and vocational training towards skills needed

by the private sector.

Introduce/improve unemployment insurance schemes to ensure the unemployed receive minimum income but

have proper incentives to look for work.

Invest in infrastructure while increase the efficiency of public investment.

Enhancing bidding procurement processes.

The Road to a More Diverse Economy

Improve the climate for FDI, including in non-oil industry, by lowering entry requirements, creating investment

promotion intermediaries and streamlining tax structures.

Promote deeper integration in global value chains by enhancing efficiency in production, bolstering managerial

quality, improving technological capacity and ensuring wage competitiveness.

Support horizontal diversification by enhancing allocation of government oil revenues in a manner that

reduces production costs in new sectors and raises their efficiency while encouraging entry of new investors.

Enhance vertical diversification in existing sectors by focusing on moving into higher value-added products in

the mineral and chemical industries.

Enhance labor market competitiveness through greater focus on wage growth in line with productivity.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Sources: IMF Regional Economic Outlook database; and Microsoft Map Land.

Note: The country names and borders on this map do not necessarily reflect the IMF's official position. Country ISO-3 codes are in brackets.

Algeria (DZA)

39.5

5,406

Libya (LBY)

6.2

6,671

Saudi Arabia (SAU)

30.8

24,252

Iraq (IRQ)

34.3

6,520

Yemen (YEM)

27.5

1,574

Oman (OMN)

3.7

20,927

Qatar (QAT)

2.2

93,990

United Arab Emirates (UAE)

9.3

42,944

Bahrain (BHR)

1.3

26,701

Population, millions (2014)

GDP per capita, U.S. dollars (2014)

Kuwait (KWT)

4.0

43,168

INTRODUCTION

1. This paper was produced at the request of the Arab Monetary Fund to support a

discussion among Arab Finance Ministers on the key challenges and policy issues related to

economic diversification in oil-exporting Arab countries.

1,2,3

The paper is organized in two parts.

The first part lays out the stylized facts on oil-exporting Arab countries as well as the motivation for

economic diversification. It underlines the heterogeneity in conditions across oil-exporting Arab

countries and therefore the need to tailor policy advice to country circumstances. It emphasizes that

the current context of likely durably lower oil prices increases the need for economic diversification

while reducing the means to promote it. The second part discusses the policies to support greater

economic diversification. It argues that macroeconomic stability and a supportive regulatory and

institutional framework are necessary, but not sufficient conditions for diversification. It then

discusses how the public sector can enable, rather than compete with, private sector development.

Finally, it sketches how the road to a more diverse economy may look like, drawing from other

country experiences.

1

The paper focuses on the countries in the Middle East and North Africa region that export oil. These are: Algeria,

Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

2

The paper was produced by a team led by Jean-François Dauphin and comprising Jean-Frédéric Noah Ndela,

Xiangming Fang and Greg Auclair, under the supervision of Aasim M. Husain. Kadia Kebet and Geraldine Cruz

provided editorial support.

3

The paper benefited from suggestions made by participants at the meeting of Arab deputy finance ministers that

took place in Abu Dhabi on January 13, 2016.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

BACKGROUND

Oil-exporting Arab countries face three-pronged policy challenges: creating jobs in line with rapidly

growing population, sheltering their economy from volatility of oil prices and ensuring sustainable

growth once oil resources are depleted. This section lays out key stylized facts about oil-exporting Arab

economies and makes the case that greater economic diversification would help address these

challenges.

A. Stylized Facts About Oil-Exporting Arab Countries

4

2. Oil-exporting Arab economies are all heavily dependent on oil. In all of these countries,

economic activity, fiscal revenue, export earnings and foreign exchange are directly and indirectly

dependent on oil production to a large extent (Figure 1).

5

Activity. Hydrocarbon and government activities (which are heavily funded by oil revenues)

account for the majority of total GDP in all countries, except in Algeria, Bahrain and Yemen and

the UAE. In Libya for example the non-oil and non-government share in GDP accounts for just

about

1

/

6

th

of total GDP. Furthermore, activity in non-government, non-oil sectors is itself often

dependent on oil as the main sources of manufacturing value-added in Arab oil exporters tend

to include refinery, chemical, and other mining/extractive industries, i.e. activities that derive

from the oil industry and some non oil sectors (e.g., construction in some countries) depend

heavily on government contacts (Table 1).

Fiscal revenue. Oil is the primary source of government revenue in all countries. In 2014, the

share of oil revenue in total revenue ranged from 47 percent in Yemen to 94 percent in Iraq and

averaged 77 percent across the group.

Exports. Similarly, in all countries except the UAE, oil is the main export good. Oil accounts for

above 80 percent of total exports in half of the countries in the group, and above 60 percent in

all of them except the UAE. In the UAE (as in Bahrain), non-oil exports include a large share of

re-exports.

6

4

For cross-country consistency, the data used in this paper draws where available on the October 2015 Regional

Economic Outlook and World Economic Outlook. More recent data vintages may be available for particular countries

and particular data.

5

For simplicity, the paper uses the term “oil” to mean hydrocarbons. In some countries (e.g., Algeria, Qatar),

hydrocarbon production includes a significant share of gas.

6

Re-exports accounted 24 percent of total non-oil exports of the UAE in 2014 according to the UN Comtrade

database.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

11%

27%

62%

Algeria

Government Oil Other

11%

24%

65%

Bahrain

12%

47%

41%

Iraq

11%

63%

26%

Kuwait

45%

39%

16%

Libya

11%

56%

33%

Oman

6%

51%

43%

Qatar

12%

43%

45%

Saudi Arabia

3%

34%

63%

United Arab Emirates

10%

19%

71%

Yemen

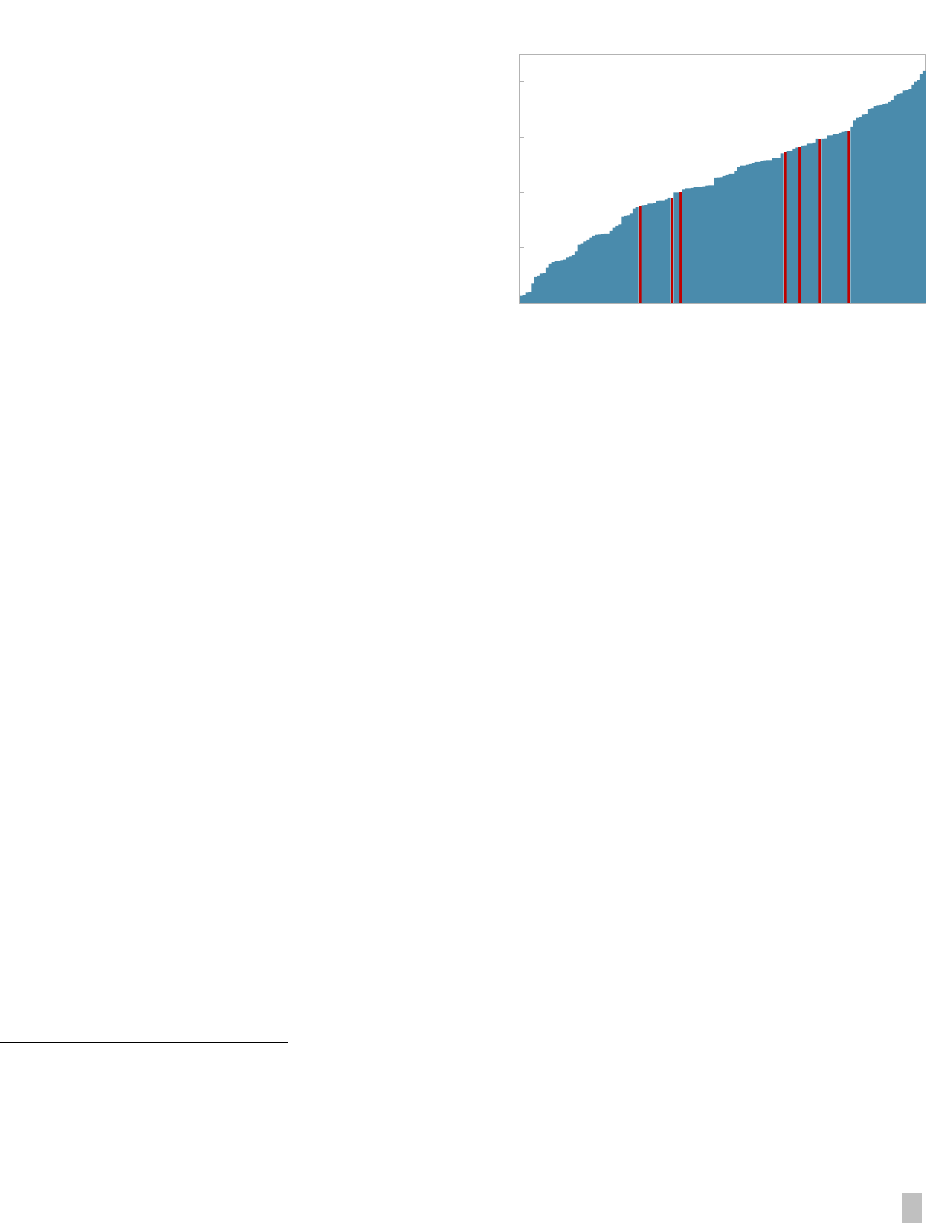

Figure 1. Selected Indicators for Arab Oil Exporters

GDP Composition of Arab Oil Exporters, 2014

1/

Sources: WEO; and IMF staff estimates.

1/ In absence of consistent data public administration value added, government GDP is proxied in this graph by the

government wage bill. See Appendix 1.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Non-oil revenue

Oil revenue

Oil and Non-Oil Fiscal Revenue, 2014

(Percent of total government revenue)

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Oil and Non-Oil Exports, 2014

(Percent of total)

Non-oil exports

Oil exports

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

Advanced Countries

SSA

GCC

Non-GCC Arab OEs

MENA OIs

EMDCs

LICs

EMD Asia

DZA

BHR

IRQ

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

YEM

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

0 5 10 15 20

Youth Employment Rate (Ages 15

-24)

Total Unemployment Rate

Total Unemployment vs. Youth Unemployment, 2013

(Percent of labor force)

Sources: ILO; World Bank; and IMF staff estimates.

Trendline for all countries

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

Table 1. Arab Oil Exporters: Key Sectoral Indicators

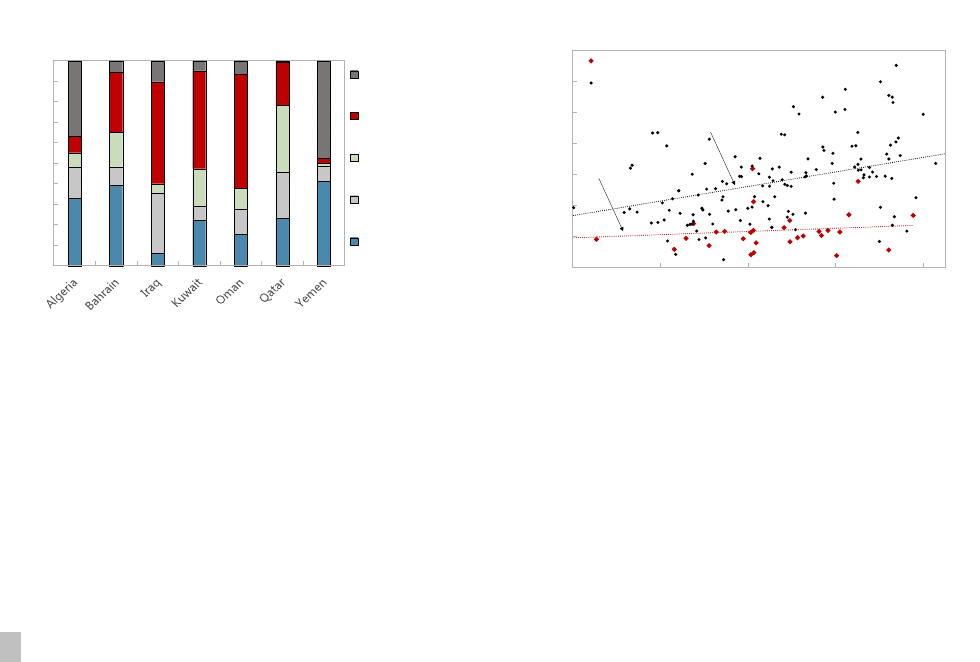

3. Reflecting the predominance of the oil sector, economic diversification is generally

low in oil-exporting Arab countries (Figure 2, Box 1). Although some countries have made more

headway than others in diversifying their economies, most indicators of economic complexity,

diversity, and export quality are lower in oil-exporting Arab economies than in many emerging

market economies, including other countries in the region and commodity exporters in other

regions.

7

Furthermore, as discussed below, the integration in global value chains remains low.

7

Many oil exporting Arab countries have launched over the years initiatives to support a more diversified economy.

For example, the UAE has promoted the development of industrial zones and the restructuring of industrial sectors;

Algeria implemented large infrastructure projects; in Kuwait, a new Development Plan focuses on large infrastructure

projects and is largely financed through partnerships with the private sector.

Agriculture Industries Services Agriculture Industries

Total

Government

Algeria 8.6 48.3 43.1 14.0 13.4 72.6 32.0

Petroleum, petrochemical, natural gas, light

industries, mining, electrical, and food processing

Bahrain 0.3 47.1 52.2 1.0 32.0 67.0 11.6

Petroleum processing and refining, aluminum

smelting, iron pelletization, fertilizers, Islamic and

offshore banking, insurance, ship repairing, tourism

Iraq 3.3 64.5 32.2 21.6 18.7 59.7 40.0

Petroleum, chemicals, textiles, leather, construction

materials, food processing, fertilizer, metal

fabrication/processing

Kuwait 0.3 49.4 50.2 … … … 27.1

Petroleum, petrochemicals, construction materials

and cement, shipbuilding and repair, water

desalination, and food processing.

Libya 2.0 45.8 52.2 17.0 23.0 59.0 …

Petroleum, petrochemicals, aluminum, iron and steel,

food processing, textiles, handicrafts, cement

Oman 1.3 55.2 43.5 … … … 11.0

Crude oil production and refining, natural and

liquefied natural gas, construction, cement, copper,

steel, chemicals, optic fiber

Qatar 0.1 68.0 31.9 1.3 54.9 43.8 12.1

Liquefied natural gas, crude oil production and

refining, ammonia, fertilizers, petrochemicals, steel

reinforcing bars, cement, commercial ship repair

Saudi Arabia 2.0 59.7 38.3 6.7 21.4 71.9 30.7

Crude oil production, petroleum refining, basic

petrochemicals, ammonia, industrial gases, sodium

hydroxide (caustic soda), cement, fertilizer, plastics,

metals, commercial ship repair, commercial aircraft

repair, construction

United Arab Emirates 0.6 58.9 40.5 7.0 15.0 78.0 28.4

Petroleum and petrochemicals; fishing, aluminum,

cement, fertilizers, commercial ship repair,

construction materials, handicrafts, textiles

Yemen 9.2 26.8 64.0 … … … 12.2

Crude oil production and petroleum refining; small-

scale production of cotton textiles, leather goods;

food processing; handicrafts; aluminum products;

cement; commercial ship repair; natural gas

production

Sources: Authorities' data and IMF staff estimates.

Share of GDP (Percent)

Main industries

Share of employment (Percent)

Services

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

DZA

KWT

LBY

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

YEM

-2.5

-2.0

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

5.25 6 6.75 7.5 8.25 9 9.75 10.5 11.25 12

Economic Complexity, 2014

(higher score = greater economic complexity)

Log of GDP per Capita (in USD), 2010-14

Hydrocarbon exports <25% of total

Hydrocarbon exports >25% of total

Trend for hydrocarbon exporters

Trend for non-hydrocarbon exporters

Economic Complexity Index and GDP per Capita

DZA

KWT

LBY

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

YEM

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

5.25 6 6.75 7.5 8.25 9 9.75 10.5 11.25 12

Export Diversity Index, 2014

(higher score = greater export diversity)

Log of GDP per Capita (in USD), 2010-14

Export Diversity Index and GDP per Capita

Hydrocarbon exports <25% of total

Hydrocarbon exports >25% of total

Trend for hydrocarbon exporters

Trend for non-hydrocarbon exporters

Figure 2. Measures of Economic Diversity

Sources: The Observatory of Economic Complexity; The Diversification Toolkit (IMF); UNIDO INDSTAT4 Industrial Statistics

Database; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: Scales for Economic Complexity, Export Diversity, and Export Quality indices are normalized between 0 (minimum

observed valued) and 1 (maximum observed value) to facilitate comparison.

Yemen

Algeria

Qatar

Oman

Kuwait

Saudi Arabia

United Arab Emirates

Morocco

Jordan

Turkey

Indonesia

Canada

Malaysia

Mexico

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

Economic Complexity Index

(1 = greater complexity)

Economic Complexity Index

Arab Oil Exporters

MENA Region Other Oil Exporters

Kuwait

Yemen

Saudi Arabia

Algeria

Qatar

Oman

United Arab Emirates

Bahrain

Turkey

Jordan

Morocco

Malaysia

Mexico

Indonesia

Canada

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

Export Diversity (IMF)

(1 = greater diversity)

Export Diversity Index

Arab Oil Exporters MENA Region Other Oil Exporters

Yemen

Iraq

Saudi Arabia

Kuwait

Oman

Algeria

United Arab Emirates

Qatar

Bahrain

Morocco

Jordan

Turkey

Indonesia

Mexico

Malaysia

Canada

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Export Quality (IMF)

(1 = higher quality)

Export Quality Index

Arab Oil Exporters MENA Region Other Oil Exporters

Qatar

Algeria

Oman

Yemen

Kuwait

Bahrain

Saudi Arabia

Morocco

Jordan

Turkey

Mexico

Indonesia

Malaysia

Canada

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Manufacturing Value Added GINI

(1 = greater inequality between sectors)

Manufacturing Value-Added GINI

Arab Oil Exporters MENA Region Other Oil Exporters

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

Box 1. Measuring Economic Diversification: Concepts and Indicators

Economic diversification can be defined and measured in various ways. Beyond simpler measures of sectoral

diversification, this paper measures diversification through four specific indicators from the literature:

1

Economic Complexity Index: This index measures the number of products made by an economy and controls

for the likelihood that the same product is also made by others. Countries that produce goods or services that

are not made elsewhere receive higher complexity scores than countries whose products are widely

manufactured. For example, Germany and Japan have high scores, because they manufacture a wide array of

products that very few countries can make. Like the IMF indices (described below), the Economic Complexity

Index relies on international trade data. It is based on the assumption that countries will export most high-

quality products, and thus, trade data will reflect overall production within the economy.

IMF Export Diversification Index: The IMF Export Diversification Index is calculated using trade data and is a

combined measure of the ‘extensive’ and ‘intensive’ dimensions of diversification (also available as separate

indices):

Extensive export diversification reflects an increase in the number of export products or trading

partners.

Intensive export diversification considers the shares of export volumes across active products or

trading partners.

A country is less diversified when export revenues are driven by only a few sectors, trading partners, and/or

total market share is low. Countries with a large number of exports and trading partners improve their

extensive diversification, which in turn provides resilience to market or trading-partner shocks. Claiming

greater market share (by product or country) increases intensive diversification, which confers greater pricing

power and integration into supply-chains. The Theil index, a measure of inequality, is calculated for the

intensive and extensive components of each country/year pair and summed to create a synthetic indicator.

IMF Export Quality Index: This index describes the average quality within any product category. The baseline

methodology (see Henn et al., (2013) for more details) estimates quality based on trade price, which is

calculated in turn based on three factors: product unit value relative to market prices; exporter income per

capita (as a proxy for differences in production technologies); and the distance between importer and exporter.

Manufacturing Value-Added Gini: This is a Gini index constructed on the relative value-added of different

manufacturing industries within an economy. The data come from the 2015 UNIDO INDSTAT4 Industrial

Statistics Database, which provides manufacturing data disaggregated at the ISIC 3-digit level, including the

total value added of each industry classified. A score of 0 indicates complete equality between industries’

value-added within an economy, while a score of 1 indicates the complete dominance of only one industry.

1/

Henn, C., C. Papageorgiou, and N. Spatafora, 2013, “Export Quality in Developing Countries” IMF Working Paper 13/108.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

4. The private sector in most oil-

exporting Arab countries also remains small

in size. Many firms in oil-exporting Arab

countries are state-owned and operate in public

related services and the private sector remains

small in many of these economies. By measures

of average firm size and new firms per 1000

residents, the private sector of oil-exporting

Arab economies tends to be largely informal or

relatively underdeveloped in non-GCC countries.

5. The size of the economies and GDP per capita vary significantly across countries. Saudi

Arabia has the largest economy, with a nominal GDP of US$746 billion while Bahrain is the smallest

of all, with a GDP of US$34 billion. The disparity in 2014 per-capita-GDP is very large: Qatar had one

of the highest per-capita-GDP in the world at close to US$94,000 (and the highest in the world when

measured in purchasing power parity terms).

Conversely, Yemen had a GDP per capita of

US$1,574 in 2014. There were also significant

variations in real GDP-per-capita growth across

countries in the group, but in all countries

except Iraq it was lower than the world average

of 3.1 percent over 2010-14. Over that period,

GDP per capita declined in Yemen and Oman in

real terms. When oil and government sectors

are excluded (as a measure of the wealth-

generating value added produced outside the

oil sector), the remaining GDP per capita is fairly

low in most countries. Only a few Arab oil exporter economies would have per capita GDPs above

the world average.

8

6. Although their sizes vary considerably, populations in most oil-exporting Arab

countries are young and fast growing. In 2014, national population sizes varied from 630,000 in

Bahrain to nearly 40 million in Algeria. With the exception of war-torn Libya, overall populations

tended to grow fast, with average annual growth rates over 2010-14 ranging from 1.5 percent in

Bahrain to 6.6 percent in Qatar. While the source of population growth is domestic in some

countries, like Algeria, a number of Gulf countries rely heavily on migration for labor. Around

10 million migrants are in Saudi Arabia, a third of the total population, while other GCC countries

also host large expatriate populations, often more than half of total population. Overall, the share of

children ages 15 and younger in the national population is high, although in GCC countries, the

large expatriate presence skews the overall population more towards working ages. Populations are

8

The world average total GDP per capita was estimated at 10,848 nominal USD in 2014.

1.1

1.1

2.8

3.5

7.2

11.3

11.7

17.7

27.6

44.4

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Non-Government, Non-Oil GDP per Capita, 2014

(In thousands of USD)

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

Qatar

United Arab Emirates

Oman

Algeria

Iraq

Turkey

Jordan

Morocco

Canada

Mexico

Indonesia

0

5

10

15

20

New businesses per 1000 residents

New Businesses per 1000 Residents, 2008-12 (Average)

Sources: World Bank Enterprise Surveys; WEO; and IMF staff estimates.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

predominately urbanized, except in Yemen. The relatively high fertility rates in a number of Arab oil

exporter countries indicate that their populations will continue to grow in the near future.

Table 2. Arab Oil Exporters: Selected Economic Indicators, 2014

B. The Case and Context for Economic Diversification

7. The oil sector cannot be a sustainable source of jobs to absorb the growing workforce.

The dominance of oil in oil-exporting Arab economies contributes to shape the economic structure

toward energy intensive activities and/or energy dependent services. However, the energy industry,

is typically highly capital intensive and generates fewer jobs than other sectors.

Algeria Bahrain Iraq Kuwait Libya Oman Qatar

Saudi Arabia

UAE Yemen

(In percent, unless otherwise specified)

Activity

Nominal GDP (billions of US$) 213.5 33.9 223.5 172.6 41.1 77.8 210.1 746.2 399.5 43.2

Nominal GDP per capita (US$) 5,406 26,701 6,520 43,168 6,671 20,927 93,990 24,252 42,944 1,574

Nominal GDP (2010-14 average annual growth rate) 11.8 8.2 15.6 10.5 10.3 11.1 17.2 12.2 9.7 13.2

Oil GDP (share of total nominal GDP) 27.1 24.0 46.5 62.9 38.5 56.1 51.1 42.6 34.3 19.5

Non-oil GDP (share of total nominal GDP) 72.9 76.0 53.5 37.1 61.5 43.9 48.9 57.4 65.7 80.5

Real GDP (2010-14 average annual growth rate) 3.1 4.0 6.5 3.4 2.0 4.5 9.3 5.2 4.5 0.4

Real GDP per capita (2010-14 average annual growth rate) 0.8 2.5 3.8 0.6 0.9 -0.7 2.9 2.3 1.9 -2.5

Real oil GDP (2010-14 average annual growth rate) -3.0 2.7 6.0 3.4 11.6 2.8 8.7 3.4 5.0 4.6

Real nonoil GDP (2010-14 average annual growth rate) 6.4 4.4 7.2 3.6 1.0 6.2 10.3 6.8 4.3 0.2

Fiscal revenue (2014)

Oil revenue (share of total)

1

59.2 86.2 94.4 79.8 93.4 87.9 80.3 76.8 63.5 47.3

Non-oil revenue (share of total)

1

40.8 13.8 5.6 20.2 6.6 12.1 19.7 23.2 36.5 52.7

Export of goods and services (2014)

Oil and gas exports (share of total) 91.8 60.9 95.1 87.8 97.2 60.5 85.7 80.2 28.5 72.9

Non-oil exports (share of total) 8.2 39.1 4.9 12.2 2.8 39.5 14.3 19.8 71.5 27.1

Demographics

Population (millions) 39.5 1.3 34.3 4.0 6.2 3.7 2.2 30.8 9.3 27.5

of which: nationals (millions) 39.4 0.6 … 1.3 … 1.9 0.2 20.7 1.3 …

Population (2010-14 average annual growth rate) 2.3 1.5 2.6 2.8 0.7 5.3 6.6 2.9 2.6 3.0

Population share ages 15 and younger (2013) 27.8 21 40.1 24.8 29.4 23.5 13.6 29 15.3 40.2

Fertility rate (2012, births per woman) 2.8 2.1 4.1 2.6 2.4 2.9 2.0 2.7 1.8 4.2

Unemployment rate (2013) 9.8 3.8 16.0 3.1 19.6 7.9 0.5 5.7 3.8 17.4

Youth unemployment rate (2013, ages 15-24) 24.0 27.9 34.1 19.6 51.2 20.5 1.5 28.7 9.9 29.8

Sources: ILO; World Bank; WEO; and IMF staff estimates.

1

Calculated from central government revenue for Algeria; otherwise general government is used. Oil GDP and revenue includes all hydrocarbons (oil and gas).

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Arab Oil Exporters: Oil GDP and Employment in Extractive Industries

(Share of total GDP and employment, percent)

Sources: ILO; WEO; and IMF staff estimates.

8. Furthermore, a significant share of employment in many countries is provided by the

government, financed through volatile and exhaustible oil revenue. In many oil-exporting Arab

economies, the public sector is a major source of employment. In Algeria and Iraq for instance, the

public sector absorbs more than 40 percent of total employment. On average elsewhere in the world,

about 90 percent of the jobs are provided by the private sector.

9

The fiscal cost of government

employment is mostly financed by volatile oil revenue. Maintaining the level of public employment

steady, as governments typically seek to do, transfers oil revenue volatility to the budget balance. At

the same time, the exhaustibility of oil resource jeopardizes the sustainability of public employment

in the long run while the domestic workforce in many oil-exporting Arab countries is typically young

and set to continue growing rapidly.

9

World Bank, 2012.

Oil GDP Non-oil GDP

Employed in extractive industries

Employed elsewhere

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Public sector jobs

Private sector jobs

Gap

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff calculations.

1

Note: Data for U.A.E. not included. Public sector jobs are projected by using historical growth rate (4.6%), while private sector

jobs are projected by using historical employment-non-oil growth elasticities and non-oil growth current WEO projections

(as in Behar, 2015).

2.15 million new entrants into labor force between 2014 and 2020

Illustrative Employment Outlook in the GCC

(Millions of new labor market entrants, cumulative)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Public Sector Employment

(Share of total, 2012 or latest data available)

Public sector share of

total employment

Public sector share of

employment of nationals

Sources: ILO; UNDP; authorities' data; and IMF staff estimates.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

9. A competitive private sector would provide a more sustainable source of growth and

employment. In most economies in the world, services in the private sector lead job creation,

followed by manufacturing, with the share of the agriculture typically declining. Within the private

sector, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are the primary source of job creation.

10

This suggests

that greater economic diversification, reflected in a private-sector driven economy operating in a

wide range of profitable sectors, would provide a more sustainable source of productive jobs,

reducing total employment’s exposure to volatile and exhaustible source of financing.

10. Greater economic diversification would shield the economy from the volatility of the

global oil market. Wide fluctuations in hydrocarbon prices is a key source of macroeconomic

volatility, notably in the fiscal and external sectors given the high dependence of fiscal and export

revenues on oil prices. When oil

prices drop, as they did in 2014,

oil-exporting countries experience

significant decline in government

revenue, public spending

(consequently), current account

balance and (potentially)

international reserves. Shrinking

oil revenues affect domestic

consumption as many jobs in oil-

exporting countries are directly or

indirectly linked to the

performance of the oil sector. In

downturns, many job seekers may

have fewer job opportunities,

which means less income and little

prospect for increasing households’ wealth. For example, the GCC countries experienced a long

decline in consumption per capita in the early 1980s and returned to the early 1980s level only in

the late 2000s, well after the oil price boom began.

11

Furthermore, lower fiscal spending (e.g., cut in

public investment programs) also weighs on economic activity in the short run and may reduce

medium-term potential growth. Reducing the reliance on oil revenue through greater economic

diversification is an important way of fostering a more stable economy.

10

IFC 2013: Jobs study.

11

IMF 2014: GCC diversification.

DZA

KWT

LBY

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

YEM

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-2.5 -2.0 -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5

Standard Deviation in Investment Expenditure 2005

-14

(percentage points of GDP)

Economic Complexity

Volatility of Government Investment Expenditure

and Economic Complexity, 2014

Hydrocarbon exports <25% of total

Hyrdocarbon exports >25% of total

Sources: Observatory of Economic Complexity; WEO, and IMF staff estimates.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 3. Projected Impact of the Recent Drop in Oil Prices

Sources: WEO; and IMF staff estimates.

11. Diversification would also sustain economic growth when oil resources are depleted.

As oil is an exhaustible resource, oil revenues will eventually dwindle. While some oil-exporting Arab

countries have a long oil production horizon, hydrocarbon resources in a number of others

(e.g. Bahrain, Oman) are expected to be depleted in the foreseeable future. Governments’ resources

will diminish and their capacity to support economic growth will be impaired. Sustaining growth

requires developing new sectors to take over and provide alternative sources of revenues as the oil

and gas industry dwindles. Strong private investment should become the impetus for growth when

high public investment can no longer be maintained. Moreover, it would raise non-oil production

and compensate the eventual loss of government revenue from the oil sector. A dynamic and

diverse export sector would help preserve the sustainability of the current account and provide a

more steady source of reserve accumulation. Moreover, even countries with large proven reserves

need to nurture the development of a vibrant non-oil sector to provide suitable employment

opportunities for their citizens.

$30

$40

$50

$60

$70

$80

$90

$100

$110

$120

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

GCC: Government Revenue and Expenditure

(Percent of non-oil GDP, weighted average)

GCC Total Expenditure

GCC Revenue

Brent price (USD, RHS)

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

$30

$40

$50

$60

$70

$80

$90

$100

$110

$120

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

MENA (excl. Libya): Government Revenue and Expenditure

(Percent of non-oil GDP, weighted average)

MENA Total Expenditure

MENA Revenue

Brent price (USD, RHS)

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

$30

$40

$50

$60

$70

$80

$90

$100

$110

$120

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Reserves of Arab Oil Exporters

(Percent of GDP, weighted average)

GCC

MENA (excl. Libya)

Brent price (USD, RHS)

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

$30

$40

$50

$60

$70

$80

$90

$100

$110

$120

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Current Account Balance of Arab Oil Exporters

(Percent of GDP, weighted average)

GCC

MENA

Brent price (USD, RHS)

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

12. The current environment of lower oil prices adds urgency to long-standing efforts to

diversify oil-exporting Arab economies. Oil prices have dropped dramatically since mid-2014.

Going forward, oil prices are expected to remain low, increasing only modestly over the medium

term. Therefore, oil exporters need to adjust their policies to preserve macroeconomic stability.

Absent adjustment, and with the exception of Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE, oil-exporting Arab

countries could substantially run down their fiscal buffers in the next five years or less. Thus, the

need for significant fiscal consolidation and external sector adjustment implies a more constrained

context for promoting economic diversification given the reduced fiscal space to support it. Fiscal

consolidation will also weigh on growth, adding urgency to the implementation of structural reforms

to boost potential growth and employment. Nonetheless, the current environment provides an

opportunity to move ahead with some difficult but necessary reforms, notably that of energy

subsidies.

0.15

0.16

0.17

0.18

0.19

0.20

0.21

0.22

0.23

1990

1993

1996

1999

2002

2005

2008

2011

2014

2017

2020

2023

2026

2029

2032

2035

2038

Oil Production per Capita for Arab Oil Exporters

(Barrels per day per capita)

projection →

Sources: World Bank; IEA; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: Projections for oil production use the IEA 'new policies' scenario.

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

Bahrain

Oman

Algeria

Yemen

Saudi Arabia

Qatar

UAE

Iraq

Kuwait

Libya

Gas Oil

Remaining Years of Oil and Gas Production, 2012

(Years; based on 2012 production levels)

Sources: BP 2013 Statistical Review; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: Gas production for Iraq assumes 46 billion cubic meters per year (the

regional average production). Countries sorted based on total remaining years.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

68% confidence interval

86% confidence interval

95% confidence interval

Futures

Sources: Bloomberg; IMF RES Commodities Unit, and staff calculations.

1/ Derived from prices of futures & options on January 12, 2015.

WEO Baseline

2015: $51.79

2016: $29.92

Brent Crude Oil Price 1/

(U.S. dollars per barrel)

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

POLICY DISCUSSION

A. Macroeconomic Pre-Conditions to Economic Diversification

This section discusses the macroeconomic pre-conditions to economic diversification. Drawing from the

existing literature, it argues that fostering macro-stability and insulating the economy from the impact

of oil price volatility is necessary to lay a sound foundation for the diversification of oil-exporting Arab

countries. It briefly discusses the policies needed to achieve such stability, including the appropriate

fiscal policy and framework, effective liquidity management, supportive financial sector policies,

including macro-prudential policies, and the need for a fairly valued exchange rate.

13. Macroeconomic stability and economic diversification reinforce each other. Empirical

evidence shows that countries with a diversified economic structure are more resilient to exogenous

shocks. Indeed during the great recession in 2008-09, economies with a more diversified export

structure weathered better international trade shocks.

12

Moreover, output volatility tends to be

lower in economies with a more complex structure. Likewise, volatility of government revenue

diminishes as an economy becomes more complex and diversified. In this regard, the relatively high

volatility in output and government revenue observed in oil-exporting Arab economies during

2005–14 could be partly explained by a lower degree of diversification, hence reliance on oil. In turn,

fostering macroeconomic stability through appropriate economic and financial policies is a

prerequisite to the development of a viable and diverse non-oil sector.

12

See UNDP, 2011. The study shows that East Asian economies lost 18 percent of export revenue in 2009, while Middle East and

African economies, which exhibit a higher export concentration ratio, lost about 30 percent of export revenue. This loss in export

revenue also translated in growth performance with growth in South Asia declining by 1.4 percentage points while growth in Africa

fell on average by 3.4 percentage points. Growth in Arab oil-exporting Arab countries fell by 5.7 percentage points during in 2009.

DZA

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

YEM

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

-2.5 -2.0 -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5

Standard Devation in GDP Growth 2005-14

(percentage points of GDP)

Economic Complexity

Output Volatility and Economic Complexity, 2014

Hydrocarbon exports <25% of total

Hydrocarbon exports >25% of total

Sources: Observatory of Economic Complexity; WEO and IMF staff estimates.

DZA

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

YEM

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

-2.5 -2 -1.5 -1 -0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5

Standard Deviation in Revenue 2005-14

(percentage points of GDP)

Economic Complexity

Government Revenue Volatility and Economic Complexity, 2014

Hydrocarbon exports <25% of total

Hydrocarbon exports >25% of total

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

220

2015 fiscal breakeven price

Sources: National authorities; and IMF staff calculations.

2015

oil price

269 314

Fiscal Breakeven Oil Prices, 2015

(U.S. dollars per barrel)

Sound fiscal policy and framework

14. Oil-exporting Arab economies face a number of competing fiscal objectives in both

the short and long term.

A challenge for fiscal policy stems from unpredictable oil prices fluctuations that can be very large

and sometimes persistent. As expenditure is normally stickier than revenue, most of the volatility

in oil revenue tends to translate into the fiscal

balance in the short term, complicating the

conduct of fiscal policy. An illustrative

indicator of this issue is the fiscal break-even

price for oil-exporting countries, i.e., the level

of oil prices below which budget deficits

occur absent a reduction in expenditure.

13

In

2015, none of the oil-exporting Arab

countries is estimated to have had a fiscal

break-even price below the actual oil price.

Another challenge for policymakers stems

from the exhaustibility of oil reserves and the necessity to the meet the needs of current as well as

future generations. Governments typically face pressures to distribute a large share of oil

revenues to the population in the form of current spending (wages, subsidies). However,

balancing these short-term exigencies against factors supporting intergenerational equity—i.e.

higher quality spending in health, education, and investment as well as sufficient accumulation

of assets to permit sustaining per-capita spending levels even after oil reserves run out—is

needed to lay a sound foundation for future growth. In this regard, fiscal decisions on oil

revenues allocate wealth across generations.

The decision on how much to save and how much to spend of current oil revenue is crucial in

addressing these challenges. The trade off is between spending oil revenues now to address the

needs of the current generation and investing them to build the future of next generations,

while safeguarding long-term fiscal sustainability. When appropriate, determining the amount of

savings should go beyond intergenerational issues and consider the potential volatility of prices

and the need to create buffers to guard against it. Indeed, countries that scaled up spending at a

gradual pace, and those that have stabilization buffers are better prepared to manage sharp falls

in prices.

14

13

The fiscal break-even price is also sensitive to the level of production and to the level of exchange rate.

14

See IMF Fiscal Monitor, October 2015.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

15. The current low oil prices exacerbate the challenges, calling for fiscal consolidation

that should be as growth friendly as possible. The immediate concern of most oil-exporting Arab

countries is the size of the fiscal deficits and their

impact on debt sustainability. In this context, it is

important to focus on preserving fiscal space for

growth-enhancing spending while maintaining

fiscal sustainability. Increasing non-oil revenue,

notably through a broadening of the tax base

should be an important part of the strategy.

15

Expenditure restraint and the composition of

spending are also important. High quality

investment in infrastructure and human capital is

essential to bolster the productive capacity of the

economy and support economic diversification.

However, oil-exporting Arab economies have often

responded to distribution-related pressures by

raising current spending while curtailing investment

during downtimes. Lower investment may translate

into lower potential growth while the focus on

current spending (e.g., wages and subsidies) to

support consumption may contribute to reducing

the competitiveness of the private non-oil sector,

for example by raising reservation wages as further

discussed below.

16

As oil prices are expected to

remain low for a relatively long period and some

oil-exporting Arab economies still have significant

deficiencies in areas such as infrastructure,

education and health, fiscal consolidation needs to

be implemented carefully to preserve investment in

these areas.

17

Raising the efficiency and the quality

of spending, in particular investment, would help

smooth the impact of fiscal adjustment.

15

Initiatives in that direction are receiving increasing attention in some oil exporting Arab countries today. For

example, GCC countries are considering adopting a VAT, Kuwait is considering the introduction of a profit tax; Saudi

Arabia is considering increases in excises.

16

Many oil exporting Arab countries have already started to reform energy pricing. For example, UAE has

implemented energy pricing reforms by adjusting fuel prices and increasing electricity tariffs; Algeria, Bahrain, Oman,

Qatar, and Saudi Arabia have recently implemented substantial increases in energy prices; Kuwait has raised the

prices for kerosene and diesel and further energy price reforms are under consideration.

17

Sturm et al, 2009.

Bahrain 20.4

Bahrain 24.6

Kuwait 27.0

Kuwait 31.1

Oman 17.6

Oman 22.8

Saudi Arabia 27.7

Saudi Arabia 22.8

Algeria 18.0

Algeria 18.0

UAE 8.7

UAE 10.6

2010 2013

Bahrain 6.5

Bahrain 10.2

Oman 32.2

Oman 63.7

Saudi Arabia 20.7

Saudi Arabia 18.9

Algeria 15.7

Algeria 17.4

Kuwait 66.1

Kuwait 67.1

UAE 31.5

UAE 34.4

2010 2013

Arab Oil Exporters:

Selected Spending Categories,

2010-13

(Percent of non-oil GDP)

Wages and Social Benefits 1/

Other Current

Sources: WEO and IMF staff calculations.

1/ Kuwait excluding social benefits.

Bahrain 10.1

Bahrain 5.2

Oman 25.2

Oman 24.8

Saudi Arabia 20.0

Saudi Arabia 27.1

Algeria 23.1

Algeria 16.2

Kuwait 13.9

Kuwait 11.4

UAE 6.6

UAE 3.8

2010 2013

Investment

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

16. A robust fiscal framework is needed to navigate short and long-term considerations.

As fiscal authorities seek to allocate resources to maximize short- and long-term growth, a strong

fiscal framework can help ensure that

appropriate buffers are built to manage oil

price shocks, mitigating the risk of

overspending or lowering the quality of

spending in good times and overconsolidating

when oil prices fall (a real risk in the current

situation). A strong fiscal framework would

also support long-term sustainability and

intergenerational equity goals. Such a

framework needs to rely on long-term fiscal

anchors and may include a fiscal rule, for

instance based on non-oil deficit that is

consistent with the permanent income hypothesis. In the current environment, a fiscal rule could

help lock in the needed adjustment after it has been achieved. A stronger fiscal framework can be

supported by dedicated oil funds, the use of which should be governed by clear and transparent

rules and fully integrated with the budget. While the appropriate rule and the sequence of fiscal

reforms will vary across countries, oil-exporting Arab economies should continue to strengthen their

fiscal framework to help better align desirable and projected policies. Some countries have made

headways in that direction. Qatar for instance established a 10-year cap on public investments and

has prepared a draft medium-term fiscal framework and showed expenditure restraint even before

oil prices fell. Even countries with large proven reserves and a budgetary surplus might need

additional efforts in that direction to promote greater intergenerational equity.

Effective liquidity management

17. Domestic liquidity needs to be shielded from oil revenue fluctuations. Oil revenue

volatility poses particular challenges for the implementation of monetary policy and to financial

stability.

Many oil-exporting Arab economies, until recently, faced excess liquidity. This weakened

monetary policy transmission channels and increased risks of credit booms and inflation

volatility.

The recent decline in oil prices has contributed

to a drying up of excess liquidity in many oil-

exporting Arab economies (e.g., Algeria, the

GCC) and a concern is whether liquidity might

become too tight in some countries. Oil price

downturns are typically associated with large

drawdowns in government deposits in the

banking system—as the government attempts

to sustain spending levels—which in turn

-30

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

Bahrain Kuwait Oman Qatar Saudi

Arabia

UAE Algeria Iraq Libya

Gap between Projected Fiscal Balances and Desirable Policies

(Percentage points of non-oil GDP)

Current Policies

Optimistic Scenario

Source: IMF staff calculations

Note: Difference between the projected medium-term non-oil primary balance (NOPB) and the NOPB recommended by the

Permanent Income Hypothesis. The high-growth scenario assumes higher non-oil growth by 1 ppt annually.

Libya

Likely policies: -56

High growth: -50

GCC

Non-GCC MENA

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Average Growth in Arab Oil Exporters'

Credit to the Private Sector and Oil Price, 2001-14

Cyclical component of oil price (USD)

Change in credit-to-GDP ratio in following year (percent)

Sources: WEO and IMF staff estimates.

Note: Calculated as a simple average. Excludes Iraq, Libya, and Yemen.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

contributes to a sharp decline in money supply (as both net foreign assets and net domestic

claims decline). The commercial banking system could be exposed to a liquidity crunch as

deposits dry up, which could lead to a sharp surge in interest rates. Moreover, tight liquidity

conditions could also affect private sector credit growth further—particularly as government

borrowing from banking system picks up—exposing the financial system to additional pressure.

18. Effective liquidity management involves better calibrating liquidity for banks, which

can be supported by the use of a government savings vehicle that invests externally, such as a

sovereign-wealth fund. Effective liquidity management would help improve the interest rate

transmission channel of monetary policy. Enhancing liquidity forecasting and putting in place

measures to appropriately calibrate liquidity in banks, including facilities to respond to bank liquidity

needs and development of appropriate collateral, could help reactivate the interbank market where

it has been dormant and facilitate the implementation of an interest-rate based monetary policy

framework. Improving liquidity management and reducing interest rate distortions would also help

deepen the financial sector, thus allowing financial markets to effectively perform the critical

functions of price setting, asset valuation, arbitrage, capital raising, and risk management that are

needed to support economic diversification. Sovereign-wealth funds invested abroad are also

helpful tools to insulate domestic liquidity from large swings in oil revenue.

18

Supporting financial policies

19. Oil price shocks could amplify the buildup of vulnerabilities in the financial system

through macro-financial linkages. As noted, during oil price upturns deposits in the banking

system tend to increase on the back of stronger fiscal position and surpluses in oil-corporate sector,

which typically leads to excess liquidity. As liquidity becomes easy, households and corporates may

be encouraged to excessive investment financed by borrowing—particularly in real estate, which

could trigger rapid credit growth, balloon bank balance sheets, and create asset bubbles. In the

event of an oil price downturn, these developments could reverse rapidly, further amplifying strains

in the financial sector and the real economy.

20. Financial policies can help mitigate risks to the financial sector and support economic

diversification. Strong regulatory and supervisory frameworks are necessary to stem risks to the

financial sector. Moreover, macro-prudential measures could prove useful in shielding the economy

from financial shocks resulting from the buildup of vulnerabilities in the financial system.

Countercyclical macroprudential policies would help mitigate credit risk and liquidity risk to financial

stability generated by the feedback loops between oil price movements, bank balance sheets, and

asset prices. Specifically, policymakers could implement countercyclical capital and liquidity buffers

and dynamic loans provision in good times to increase the resilience of the financial system, and

18

Among oil-exporting Arab countries, Bahrain, Kuwait, Libya, Qatar, and the UAE have such sovereign wealth funds.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

reduce the procyclical feedback between asset prices and credit.

19

Portfolio and/or financial

diversification would help mitigate concentration risk, particularly in GCC.

A fairly valued real exchange rate

21. A fairly valued real effective exchange rate is essential to economic diversification.

Economies that are highly specialized in extractive industries could fail to develop thriving secondary

or tertiary sectors because of rampant Dutch disease (i.e., situations where the dominant sector in

the economy causes a currency real appreciation that reduces the incentive to invest in other export

sectors). Such currency overvaluation would exacerbate the distortions in the relative price of

tradable and non-tradable goods. This would amplify the inefficiency in the allocation of production

factors across sectors and dampen prospects of new sources of growth. Conversely, an undervalued

real effective exchange rate may lead to short-term gains, but such gains tend to be offset by long-

term drawbacks stemming from an inefficient allocation of resources as most of the gains might lie

in firms that are less competitive than foreign peers and only survive because they exploit distorted

relative prices.

20

B. Regulatory and Institutional Frameworks Conductive to Private Sector

Growth

This section discusses the regulatory and institutional preconditions for private sector growth, including

improving the business environment, reducing regulatory barriers to competition, fostering greater

trade integration, reforming labor markets and facilitating greater access to finance.

22. A business environment conducive to private sector growth is necessary for economic

diversification. The business environment plays a key role in promoting private sector development

and hence greater economic diversification. While the business climate in GCC countries remains

relatively favorable, other oil-exporting Arab countries (Algeria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen) rank low in

the World Bank’s doing business indicators. Beyond this disparity, the region faces common

challenges to improve the business climate. These include increasing the efficiency of government

administration (e.g., by streamlining procedures, establishing e-government), improving the legal

framework for the conduct of business (e.g., to resolve insolvency, enforce contracts, protect

minority investors) and fostering greater access to credit (Figure 4). Government efforts should

address these issues to ensure that private enterprises operate in an efficient, transparent, and

streamlined environment.

19

See also “Oil Prices, Financial Stability, and the Use of Countercyclical Macroprudential Policies in GCC,” IMF, 2015

forthcoming.

20

Rodrick, 2008.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

23. Reducing regulatory barriers to competition would also benefit economic

diversification by raising productivity. Many sectors in oil-exporting Arab countries are

dominated by state ownership. This high concentration level is a potential source of inefficiency in

domestic markets and impedes the development of the private sector. Reviewing relevant

regulations to increase competition would provide firms with incentives to reallocate resources to

more productive industries and be better equipped to survive fierce market competition.

21

In this

regard, competition authorities and competition laws should be strengthened to open up markets

to private enterprises. For instance, in Kuwait, a review of the competition policy law and its

implementation and of policies related to barriers to entry could help increase competition.

24. Greater trade integration could support export diversification. Arab countries are fairly

integrated through labor mobility and infrastructure but, intra-regional trade flows remain low

(about 12 percent on average) and largely consists in trade in oil. The Pan-Arab Free Trade Area

(PAFTA, 1997) and the Unified Economic

Agreement between members of the Gulf

Cooperation Council (UEA-GCC, 1998) do not

appear to have significantly boosted intra-regional

trade. Non-tariff barriers, such as lengthy customs

clearance procedures and high number of

documents and signatures needed to process a

trade transaction, remain important barriers to

intra-Arab trade. Promoting deeper regional

integration among Arab countries would require

reducing these barriers, liberalizing trade services

and strengthening rules applicable to regional

21

IFC 2013: Jobs study.

0

5

10

15

20

25

Share of Exports Going to the MENAP Region

(Percent of total)

2000 2014

Sources: Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) and IMF staff estimates.

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

-5 0 5 10 15

Change in Doing Business Distance to Frontier, 2010

-13

Average Real GDP Growth, 2011-14

Doing Business Distance to Frontier and GDP Growth, 2010-14

Top quartile (change in DB DTF)

Bottom quartile (change in DB DTF)

Sources: World Bank Doing Business (2015); and IMF staff estimates.

Note: an unequal variances t-test finds that the sample means are different (p<0.01).

Average GDP growth

for top quartile (4.5)

Average GDP growth

for bottom quartile (2.6)

DZA

BHR

IRQ

KWT

LBY

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

YEM

25

35

45

55

65

75

85

95

5.25 6 6.75 7.5 8.25 9 9.75 10.5 11.25 12

DB Distance to Fronteir, 2010-14

(higher score = fewer barriers to business)

Log of GDP per Capita (in USD), 2010-14

Doing Business and GDP per Capita, 2014

Hydrocarbon exports <25% of total

Hydrocarbon exports >25% of total

Sources: World Bank Doing Business (2015); WEO.

Trend for hydrocarbon exporters

Trend for non-hydrocarbon exporters

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Overall

Starting a Business

Dealing with

Construction Permits

Getting Electricity

Registering Property

Getting Credit

Protecting Minority

Investors

Paying Taxes

Trading Across Borders

Enforcing Contracts

Resolving Insolvency

Doing Business Distance to Frontier

Non-GCC MENA

(100 = no barriers to business)

Algeria Iraq Yemen

trade.

22

Owing to a number of factors including geographical proximity and relative homogeneity in

economic structures, GCC countries are more integrated than the rest of the region. Some countries,

such as Bahrain, have seen opportunities arising from ongoing regional business integration,

particularly with Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE.

Figure 4. Most Problematic Factors for Doing Business in Arab Oil Exporters

Source: World Bank Doing Business Indicators, 2015.

22

Chauffour, 2012.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Overall

Starting a Business

Dealing with

Construction Permits

Getting Electricity

Registering Property

Getting Credit

Protecting Minority

Investors

Paying Taxes

Trading Across Borders

Enforcing Contracts

Resolving Insolvency

Doing Business Distance to Frontier

GCC

(100 = no barriers to business)

Bahrain Kuwait Oman

Qatar Saudi Arabia UAE

Factor:

Algeria

(2012)

Bahrain

(2011)

Kuwait

(2013)

Libya

Oman

(2011)

Qatar Saudi Arabia UAE Yemen

Inadequately educated workforce

Access to financing

Restrictive labor regulations

Inefficient government bureaucracy

Poor work ethic in national labor force

Inadequate supply of infrastructure

Corruption

Policy instability

Insufficient capacity to innovate

Inflation

Government instability/coups

Foreign currency regulations

Tax rates

Crime and theft

Tax regulations

Poor public health

1-3 most common responses

4-6 most common responses

7-9 most common responses

10-16 most common reponses

Source: World Economic Forum Executive Opinion Survey, 2014 or latest year available. From a list

of 16 factors, respondents are asked to select the five most problematic and rank them from 1

(most problematic) to 5.

Note: Grayed-out cells do not have data available.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

25. Reviewing labor regulations can also help foster greater private-sector led job

creation. Although labor markets are relatively flexible in most GCC countries, regulations are

considered restrictive in some areas as evidenced by the Executive Opinion Survey undertaken by

the World Economic Forum (Figure 4). In other countries (e.g., Algeria, Kuwait, Oman and, to a lesser

extent, Saudi Arabia) insufficient labor market

flexibility is seen as a hindrance.

23

Various

degrees of labor market reforms are underway

in a number of countries. For instance, Saudi

Arabia has been implementing labor market

reform to streamline regulations while seeking

to improve work conditions. Regulations on

female employment have been eased, with

more sectors being opened for their

employment. Oman is updating the labor law

governing Omani and foreign workers, by

amending issues related to labor dispute

resolution, working conditions in the private

sector, and working conditions for women. Other oil-exporting Arab economies would also benefit

from reforms in labor regulations aiming to increase labor force flexibility while fostering better

working conditions and introducing unemployment insurance schemes where they do not exist.

26. Inadequate access to finance is a key factor inhibiting private sector development.

Access to finance is an important condition for private sector growth. The oil-exporting Arab

countries have a relative low percentage of firms with credit lines or loans from financial institutions,

and only a small portion of bank lending goes to SMEs. For instance, while credit growth is strong in

these countries, bank lending to private

sector only accounts for 10-30 percent

of non-oil GDP in Algeria, Iraq, and

Yemen. Further efforts to reform

financial system, reduce directed

lending, and develop domestic security

markets will be important to support

the financing of the private sector.

Specific measures would vary across

countries. Algeria, for instance, needs to

foster the development of the local

debt market to diversify financing

options for the corporate sector. Iraq

could continue to lift the restrictions

placed on private banks in obtaining government business.

23

Global Competitiveness Report, 2014-15.

Algeria

Kuwait

Oman

Saudi Arabia

Bahrain

Qatar

UAE

2

3

4

5

6

Labor Market Efficiency

(1-7 scale, 7 = best)

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Index (2015).

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

Allocation of Domestic Credit to the Economy, 2014

(Percent of non-oil GDP)

Credit to private sector

Credit to public sector/SOEs

Credit to financial sector

Source: IMF staff estimates.

ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION IN OIL-EXPORTING ARAB COUNTRIES

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27

27. Financial constraints tend to be more binding for SMEs. Insufficient financing is an

important bottleneck hindering SMEs’ ability to grow into larger firms. Weak credit information and