flo14498_fm_i-1.indd i 01/08/19 07:15 PM

Businessand

Professional

Communication

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd ii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd iii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

Businessand

Professional

Communication

Putting People First

Final PDF to printer

KoryFloyd

UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

PeterWCardon

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd iv 01/08/19 07:15 PM

BUSINESS AND PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATION: PUTTING PEOPLE FIRST

Published by McGraw-Hill Education, 2 Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10121. Copyright © 2020 by

McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by

any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education, including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or

broadcast for distance learning.

Some ancillaries, including electronic and print components, may not be available to customers outside

the United States.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 LWI 21 20 19

ISBN 978-1-260-51449-0 (bound edition)

MHID 1-260-51449-8 (bound edition)

ISBN 978-1-260-24505-9 (loose-leaf edition)

MHID 1-260-24505-5 (loose-leaf edition)

Portfolio Manager: Peter Jurmu

Senior Product Developer: Kelly I. Pekelder

Marketing Manager: Gabe Fedota

Lead Content Project Manager: Christine Vaughan

Senior Content Project Manager: Keri Johnson

Senior Buyer: Susan K. Culbertson

Senior Designer: Matt Diamond

Content Licensing Specialist: Jacob Sullivan

Cover image: ©gobyg/Getty Images

Compositor: SPi Global

All credits appearing on page or at the end of the book are considered to be an extension of the

copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Floyd, Kory, author. | Cardon, Peter W., author.

Title: Business and professional communication: / Kory Floyd, University Of

Arizona, Peter Cardon, University of Southern California.

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : McGraw-Hill Education, [2020] |

Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018055794 | ISBN 9781260514490 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Business communication. | Communication in management. |

Communication in organizations.

Classification: LCC HF5718 .F595 2020 | DDC 658.4/5--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018055794

The Internet addresses listed in the text were accurate at the time of publication. The inclusion of a website

does not indicate an endorsement by the authors or McGraw-Hill Education, and McGraw-Hill Education

does not guarantee the accuracy of the information presented at these sites.

mheducation.com/highered

Final PDF to printer

v

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd v 01/08/19 07:15 PM

DEDICATION

To the mentors who trained and nurtured us, and to

the students who teach and inspire us.

KoryFloyd

—Peter Cardon

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd vi 01/08/19 07:15 PM

Final PDF to printer

vii

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd vii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

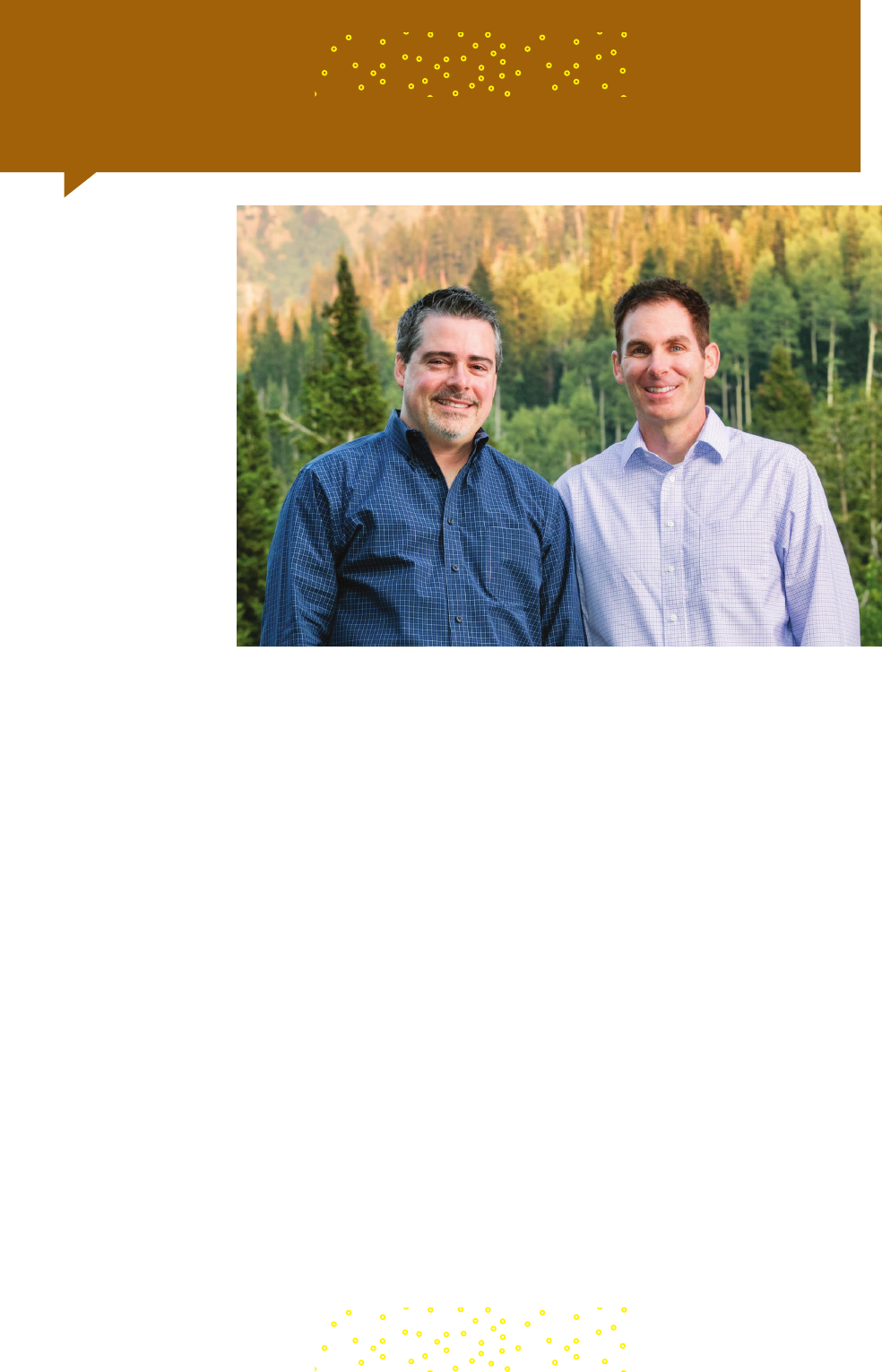

KoryFloyd is a professor of communication at the University of Arizona. His research focuses

on interpersonal communication in a variety of contexts, with particular focus on how positive

communication contributes to well-being. He has written 15 books and over 100 scientific

papers and book chapters on the topics of interpersonal behavior, emotion, nonverbal beha-

vior, and health. He is a former editor of Communication Monographs and Journal of Family

Communication. His work has been recognized with both the Charles H. Woolbert Award

and the Bernard J. Brommel Award from the National Communication Association, as well

as the Early Career Achievement Award from the International Association for Relationship

Research. As an educator, he teaches courses on interpersonal communication, communica-

tion theory, nonverbal communication, and quantitative research methods. Professor Floyd

received his undergraduate degree from Western Washington University, his master’s degree

from the University of Washington, and his PhD from the University of Arizona.

PeterCardon is a professor of business communication at the University of Southern

California. He also serves as the academic director of the MBA for Professionals and

Managers Program. His research focuses on virtual team communication, leadership

communication on digital platforms, and intercultural business communication. He has

worked in China for three years and regularly takes MBA and other business students on

company tours in China, South Korea, and other locations in Asia. He previously served

as president of the Association for Business Communication, a global organization of

business communication scholars and instructors. He is an active member of Rotary

International, a global service organization committed to promoting peace, fighting dis-

ease, providing educational opportunities, and growing local economies.

Kory Floyd (left) and Peter Cardon (right)

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd viii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

Final PDF to printer

ix

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd ix 01/08/19 07:15 PM

BRIEFCONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

CommunicatingforProfessionalSuccess

CHAPTER 2

CultureDiversityandGlobalEngagement

CHAPTER 3

VerbalandNonverbalMessages

CHAPTER 4

ListeningandLearning

CHAPTER 5

PerspectiveTaking

CHAPTER 6

EffectiveTeamCommunication

CHAPTER 7

EffectiveMeetings

CHAPTER 8

CareerCommunication

CHAPTER 9

InterviewingSuccessfully

CHAPTER 10

WritingacrossMedia

CHAPTER 11

MajorGoalsforPresentations

CHAPTER 12

PlanningandCraftingPresentations

CHAPTER 13

FindingSupportforYourPresentationGoals

CHAPTER 14

RehearsingandDelivering

SuccessfulPresentations

GLOSSARY

INDEX

Final PDF to printer

x

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd x 01/08/19 07:15 PM

APEOPLEFIRSTAPPROACH

Final PDF to printer

Arapidlyevolvingglobalworkplacerequiresstudentstodevelopavarietyofprofes

sionalskillstosucceedProfessionalsuccessoftenrestsontheabilitytolistenengen

dertrustadapttoculturaldifferencesandconsidertheperspectivesofothers

TohighlighttheseskillsinprofessionalsettingsKoryFloydandPeterCardonadopta

people first approachthatprioritizesqualityworkplacerelationships

Authentic Examples

UsingdozensofauthenticexamplesfromthebusinessworldBusinessandProfessional

CommunicationPuttingPeopleFirstemphasizeshowstudentscancommunicateinper

sonandinvirtualsettingstodevelopmeaningfulrichandproductiveprofessionalrela

tionshipsinatechnologysaturatedworld

Perspective Taking

Uniquetothemarketthistextincludesadedicatedchapterfocusedonperspective

takingcoveringtheprocessesofpersonperceptioncommonperceptualerrorsthe

selfservingbiasandthefundamentalattributionerrortheselfconceptandthepro

cessesofimagemanagementThischapterequipsstudentstounderstandandpayat

tentiontotheperspectivesofothers

Career Communication

Alsouniquetothemarket thistextincludesadedicatedchapterfocused oncareer

communicationencouragingstudentstoengageinnetworkingandtoconsiderthepri

oritiesandpointsofviewofothersastheyseekemploymentandinteractprofessionally

Recurring People First

Feature

Occurring in every chapter the People First

featurepresentsstudentswithrealisticscenar

iosthataresensitivediscomfortingortrickyto

manageItthenteachesstudentshow tonavi

gate those situations effectively Students are

givenconcreteskillsforpreservingrelationships

withothersastheyencounterthesedifficultmo

mentsandconversations

AN ONGOING FOCUS ON SKILL BUILDING, SELF-ASSESSMENT,

AND CRITICAL THINKING

Throughouteachchapterstudentsencounteropportunitiestoengageinskillbuilding

selfassessmentandcriticalthinking

●

EachchapterincludesSharpen Your Skillsfeaturesandendofchapter

Skill-Building Exercisesthatidentifyparticularcommunicationskillsandgive

activitiesforstudentstohelpbuilditthem

●

Givingstudentstheopportunitytoanalyzewheretheycurrentlyarewithrespect

toaparticulartraitThe Competent Communicatorfeatureallowsstudentsto

xi

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xi 01/08/19 07:15 PM

selfassessaspecificcharacteristictraitortendencyandprovidesinstructions

forcalculatingandinterpretingtheirscores

●

Chapter Review Questionsattheendofeachchapterstimulatecriticalthinking

andreflectionandcanbeusedtosparkinteractionintheclassroomoraswriting

assignments

AN ENGAGING, NARRATIVE-BASED APPROACH

Chaptersbeginbypresentingstudentswithanarrativeofacommunicationproblem

ordilemmaandthenconcludebyresolvingthatdilemmabyreferencingtheprinciples

throughoutthechapterEachchapterisillustratedwithrichexamplesofrealbusiness

communicatorswhichbringtheprinciplestolifeforstudentsThisinteractiveapproach

allowsstudentstoactivelyengagewiththecontentinsteadofpassivelyreadingit

Bringing It All Together

Studentspreparingtosucceedintoday’sworkplacerequiresolidtrainingincommunication

skillsandprinciplesaswellasexperienceapplyingtheminrealisticprofessionalcontexts

KoryFloydandPeterCardonbringsubstantialandconcretebusinessworldexperi

encetobearintheproduct’sprinciplesexamplesand activitiesandensurethat the

theoriesconceptsandskillsmostrelevanttothecommunicationdisciplinearefullyrep

resentedandengagedTheresultisaprogramthatspeaksstudents’languageandhelps

themunderstandandapplycommunicationskillsintheirpersonalandprofessionallives

Accolades from Our Reviewers

“ThisisthemoststudentfocusedtextthatIhaveeverreadItdealswith

therealworldproblemsthatstudentshavetoovercomeinordertobe

successfulinthecourseThereisnobettertextonthemarket”

—DRBRADLEYSWESNERSAMHOUSTONSTATEUNIVERSITY

“Aperfectblendofbusinessandcommunicationexpertisewritteninan

approachabletonethatusesrealworldexamplestoenhancestudent

engagementandlearning”

—KELLYSTOCKSTADAUSTINCOMMUNITYCOLLEGE

“Fullofrichthoughtfulusefuladviceuptodatewiththecurrentjob

marketEasytoreaduserfriendlyNotanorganizationalcommunication

textitisaperformanceenhancementtext”

—JOHNCARLMEYERUNIVERSITYOFSOUTHERNMISSISSIPPI

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

Students—study more eciently, retain

more and achieve better outcomes.

Instructors—focus on what you love—

teaching.

SUCCESSFUL SEMESTERS INCLUDE CONNECT

65%

Less Time

Grading

©Hill Street Studios/Tobin Rogers/Blend Images LLC

F I

Final PDF to printer

You’re in the driver’s seat.

Want to build your own course? No problem. Prefer to use our turnkey,

prebuilt course? Easy. Want to make changes throughout the semester?

Sure. And you’ll save time with Connect’s auto-grading too.

They’ll thank you for it.

Adaptive study resources like SmartBook® help your

students be better prepared in less time. You can

transform your class time from dull definitions to dynamic

debates. Hear from your peers about the benefits of

Connect at www.mheducation.com/highered/connect

Make it simple, make it aordable.

Connect makes it easy with seamless integration using any of the

major Learning Management Systems

—Blackboard®, Canvas,

and D2L, among others

—to let you organize your course in one

convenient location. Give your students access to digital materials

at a discount with our inclusive access program. Ask your

McGraw-Hill representative for more information.

Solutions for your challenges.

A product isn’t a solution. Real solutions are aordable,

reliable, and come with training and ongoing support

when you need it and how you want it. Our Customer

Experience Group can also help you troubleshoot

tech problems

—although Connect’s 99% uptime

means you might not need to call them. See for

yourself at status.mheducation.com

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xiii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

”

Chapter 12 Quiz Chapter 11 Quiz

Chapter 7 Quiz

Chapter 13 Evidence of Evolution Chapter 11 DNA Technology

Chapter 7 DNA Structure and Gene...

and 7 more...

13 14

©Shutterstock/wavebreakmedia

F S

Final PDF to printer

Eective, ecient studying.

Connect helps you be more productive with your

study time and get better grades using tools like

SmartBook, which highlights key concepts and creates

a personalized study plan. Connect sets you up for

success, so you walk into class with confidence and

walk out with better grades.

made it easy to study when

“

I really liked this app—it

you don't have your text-

book in front of you.

—Jordan Cunningham,

Eastern Washington University

Study anytime, anywhere.

Download the free ReadAnywhere app and access

your online eBook when it’s convenient, even if

you’re oine. And since the app automatically syncs

with your eBook in Connect, all of your notes are

available every time you open it. Find out more at

www.mheducation.com/readanywhere

No surprises.

The Connect Calendar and Reports tools

keep you on track with the work you need

to get done and your assignment scores.

Life gets busy; Connect tools help you

keep learning through it all.

Learning for everyone.

McGraw-Hill works directly with Accessibility Services

Departments and faculty to meet the learning needs of all

students. Please contact your Accessibility Services oce

and ask them to email [email protected], or

visit www.mheducation.com/about/accessibility.html for

more information.

xiv

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xiv 01/08/19 07:15 PM

ASSOCIATIONFORBUSINESS

COMMUNICATION

Final PDF to printer

xv

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xv 01/08/19 07:15 PM

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FewendeavorsofanysignificanceareachievedinisolationTherearealwaysotherswho

helpusrisetoandexceedourpotentialinnearlyeverythingwedoWearedelighted

toacknowledgeandthankthosewhosecontributionsandsupportareresponsiblefor

thebookyouarenowreading

Firstandforemostwearegratefulfortheadviceandinputofthebusinessandcom

municationinstructorswhowerekindenoughtoserveasreviewersforthistextTheir

contributionsareinvaluableandwesincerelyappreciatethetimeandenergytheyde

votedtomakingthisbookaseffectiveanduserfriendlyaspossible

Brock Adams, LouisianaStateUniversity

Gretchen Arthur, LansingCommunity

College

Benjamin Clark Bishop Jr.,DesMoinesArea

CommunityCollege

Heidi Bolduc, UniversityofCentralFlorida

Renee Brokaw, UniversityofTampa

Carolyn Cross, HoustonCommunityCollege

Kathryn Dederichs, UniversityofStThomas

Brandy Fair, GraysonCollege

Kristen A. Foltz,UniversityofTampa

Shelley Anne Friend,AustinCommunity

College

Joseph Ganakos, LeeCollege

Karley A. Goen,TarletonStateUniversity

Melissa Graham, UniversityofCentral

Oklahoma

Rebecca Greene, SouthPlainsCollege

Nancy Hicks, CentralMichiganUniversity

Kathy Hill, SamHoustonStateUniversity

Elaine Jansky, NorthwestVistaCollege

Arthur Khaw, KirkwoodCommunityCollege

Jackie Layng, UniversityofToledo

Ronda Leahy, UniversityofWisconsinLa

Crosse

Kirk Lockwood, IllinoisValleyCommunity

College

Donna Metcalf, GreenvilleUniversity

John Meyer, UniversityofSouthernMississippi

Dan Modaff, UniversityofWisconsinLa

Crosse

Steven R. Montemayor,NorthwestVista

College

Bev Neiderman, KentStateUniversity

Kelly Odenweller, IowaStateUniversity

Delia J. O’Steen,TexasTechUniversity

Aimee L. Richards,FairmontStateUniversity

Shera Carter Sackey,SanJacintoCollege

Aaron Sanchez, ArizonaStateUniversity

Sara Shippey, AustinCommunityCollege

Shavonne R. Shorter,BloomsburgUniversity

Michele Simms, UniversityofStThomas

Richard Slawsky, UniversityofLouisville

Ashly Bender Smith,SamHoustonState

University

Ray Snyder, TridentTechnicalCollege

Sherry Stancil, CalhounCommunityCollege

Kerry Strayer, OtterbeinUniversity

John Stewart, UniversityofSouthFlorida

SarasotaManatee

Kelly A. Stockstad,AustinCommunityCollege

Jenny Warren, CollinCollege

Rebecca Wells-Gonzalez, IvyTechCommunity

College

Bradley S. Wesner,SamHoustonStateUniversity

Karin Wilking, NorthwestVistaCollege

Julie A. Williams,SanJacintoCollege

Scott Wilson, CentralOhioTechnicalCollege

Wecouldnotaskforabetterteamofeditorsmanagersandpublisherstoworkwith

thanourteamatMcGrawHillWeareindebtedtoAnkeWeekesKellyPekelderGabe

FedotaPeterJurmuChristineVaughanMattDiamondLisaMooreandSarahBlasco

fortheconsistentprofessionalsupportwehavereceivedfromeachofthem

ElisaAdamsisadevelopmenteditorparexcellenceShemadenearlyeverywordof

thisbookmoreinterestingmorerelevantandmorecompellingthanitwaswhenwe

Final PDF to printer

xvi

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xvi 01/08/19 07:15 PM

wroteitWehavebeenexceedinglygratefulforherinsightsherhumorandherpa

tiencethroughoutthiswritingprocess

OurstudentscolleaguesandadministratorsattheUniversityofArizonaandthe

UniversityofSouthernCaliforniaareajoytoworkwithandatremendoussourceofen

couragementUndertakingaprojectofthissizecanbedauntinganditissovaluableto

haveastrongnetworkofprofessionalsupportonwhichtodraw

Finallyweareeternallygratefulfortheloveandsupportofourfamiliesandfriends

Oneneedn’tbeanexpertoncommunicationtounderstandhowimportantcloserela

tionshipsarebutthemorewelearnaboutcommunicationthemoreappreciativewe

becomeofthepeoplewhoplaythoserolesinourlives

Final PDF to printer

xvii

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xvii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Communicating for Professional Success 2

UnderstandingtheCommunicationProcess

SixPrinciplesofCommunication

ElementsoftheCommunicationProcess

CAREER TIP 9

CommunicationinProfessionalNetworks

NetworkersCommunicateEffectivelyinFormal

ProfessionalNetworks

NetworkersCommunicateEffectivelyinInformal

ProfessionalNetworks

NetworkersEmployManyCommunicationChannelsto

StayConnectedtoTheirNetworks

TECH TIP 11

NetworkersBuildBroadProfessionalCommunication

Networks

CultivatingCredibility

CredibleCommunicatorsBuildTrust

CredibleCommunicatorsDevelopRapport

CredibleCommunicatorsListenActively

CredibleCommunicatorsMaintainIntegrity

andAccountability

PEOPLE FIRST 13

CredibleCommunicatorsKnowandAdapt

toTheirAudiences

CharacteristicsofSuccessfulCommunicators

CommunicatingCompetently

CharacteristicsofSuccessfulCommunicators

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 16

FOCUS ON ETHICS 17

Chapter Wrap-Up 18

A Look Back 18

Key Terms 19

Chapter Review Questions 19

Skill-Building Exercises 20

Endnotes 21

CHAPTER 2

Culture, Diversity, and Global Engagement 24

AppreciatingCultureandHumanDiversity

CultureandCoculture

RaceEthnicityandNationality

SocioeconomicStatus

DisabilityStatus

SexGenderandSexuality

Religion

GenerationalIdentity

OtherElementsofIdentityandDiversity

ConductingBusinessonaGlobalScale

IdentifyingtheWaysCulturesVary

CAREER TIP 35

AdaptingtoCulturalNormsandCustoms

PEOPLE FIRST 39

AddressingDiversityinanEthicalManner

HonoringYourOwnCulturalValues

RespectingtheCulturalValuesandDiverseBackgrounds

ofOthers

SeeingCulturesandDiversityasanOpportunitytoLearn

andGrow

RecognizingtheIndividualityofOthers

TECH TIP 41

CommunicatingwithCulturalProficiency

CultivateCulturalAwareness

PracticePerspectiveTaking

AvoidCulturalCentrism

FOCUS ON ETHICS 43

AdaptingtoChangingCulturalNorms

andExpectations

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 44

Chapter Wrap-Up 44

A Look Back 45

Key Terms 45

Chapter Review Questions 46

Skill-Building Exercises 46

Endnotes 48

CHAPTER 3

Verbal and Nonverbal Messages 50

HowPeopleUseLanguage

TheNatureofLanguage

LanguageandCredibility

FOCUS ON ETHICS 56

FosteringEffectiveVerbalCommunication

SeparateOpinionsfromFactualClaims

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xviii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

xviii CONTENTS

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 58

SpeakatanAppropriateLevel

OwnYourThoughtsandFeelings

UsePowerfulLanguage

CAREER TIP 60

ChannelsofNonverbalMessages

TheFaceandEyes

MovementandGestures

PEOPLE FIRST 62

TouchBehaviors

VocalBehaviors

TheUseofSpaceandDistance

PhysicalAppearance

TheUseofTime

TECH TIP 66

TheUseofArtifacts

ImprovingYourNonverbalCommunicationSkills

InterpretingNonverbalCommunication

ExpressingNonverbalMessages

Chapter Wrap-Up 69

A Look Back 70

Key Terms 70

Chapter Review Questions 70

Skill-Building Exercises 71

Endnotes 72

CHAPTER 4

Listening and Learning 74

EffectiveListeningandLearning

WhatIsListening?

TheImportanceofListeningEffectively

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 78

StagesandStylesofEffectiveListening

StagesofEffectiveListening

TypesofListening

OvercomingBarrierstoSuccessfulListening

Noise

PseudolisteningandSelectiveAttention

TECH TIP 84

InformationOverload

FOCUS ON ETHICS 85

GlazingOver

RebuttalTendency

PEOPLE FIRST 87

ClosedMindedness

CompetitiveInterrupting

CAREER TIP 89

HoningYourListeningandLearningSkills

BecomeaBetterInformationalListener

BecomeaBetterCriticalListener

BecomeaBetterEmpathicListener

Chapter Wrap-Up 94

A Look Back 94

Key Terms 95

Chapter Review Questions 95

Skill-Building Exercises 95

Endnotes 96

CHAPTER 5

Perspective Taking 100

HowWePerceiveOthers

PerceptionIsaProcess

TheCircularNatureofPerception

WeCommonlyMisperceiveOthers’

CommunicationBehaviors

PEOPLE FIRST 107

CAREER TIP 109

CommunicatingandExplainingOur

Perceptions

WeExplainBehaviorthroughAttributions

AvoidingTwoCommonAttributionErrors

HowWePerceiveOurselves

SelfConceptDefined

AwarenessoftheSelfConcept

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 114

ManagingOurImage

CommunicationandImageManagement

FOCUS ON ETHICS 117

TECH TIP 118

CommunicationandFaceNeeds

Chapter Wrap-Up 120

A Look Back 121

Key Terms 121

Chapter Review Questions 121

Skill-Building Exercises 122

Endnotes 123

CHAPTER 6

Effective Team Communication 126

DevelopingEffectiveTeams

TeamsVaryinSeveralDimensions

TeamsGothroughFourNatural

StagestoReachHighPerformance

EffectiveTeamsBuildaWork

CulturearoundValuesNormsandGoals

EvaluatingTeamPerformance

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xix 01/08/19 07:15 PM

CONTENTS xix

FOCUS ON ETHICS 132

TeamsShouldFocusFirstand

ForemostonPerformance

EffectiveTeamsMeetOften

EffectiveTeamsEmbrace

DifferingViewpointsandConflict

EffectiveTeamsLearntheCommunication

StylesandPreferencesofTheirMembers

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 135

CAREER TIP 136

EffectiveTeamsProvidePositiveFeedbackandEvaluate

TheirPerformanceOften

LeadershipandDecisionMakingStyles

LeadersEnactDistinctStyles

LeadersManageConflictConstructively

LeadersAvoidGroupthink

PEOPLE FIRST 141

LeadersListenCarefully

TECH TIP 144

PrinciplesforVirtualTeamCommunication

FocusonBuildingTrustatEachStage

ofYourVirtualTeam

MeetinPersonattheLaunchoftheVirtualTeam

GettoKnowOneAnother

UseCollaborativeTechnologies

ChooseanActiveTeamLeader

RunEffectiveVirtualMeetings

Chapter Wrap-Up 147

A Look Back 148

Key Terms 148

Chapter Review Questions 149

Skill-Building Exercises 149

Endnotes 150

CHAPTER 7

Effective Meetings 152

PlanningforMeetings

AskEssentialQuestions

CreateandDistributeanAgenda

FOCUS ON ETHICS 156

RunningEffectiveMeetings

BeginonTime

CreateTraditionCultureandVariety

SetExpectationsandFollowtheAgenda

EncourageParticipationandExpressionofIdeas

BuildConsensusandaPlanofAction

PEOPLE FIRST 159

ClosetheMeeting

TECH TIP 161

ConductingEffectiveOnlineMeetings

LearntheFunctionsand

LimitationsofMeetingSoftware

HelpParticipantsUsetheMeetingSoftware

DecideHowtoDocumentand

DistributetheDiscussion

StarttheMeetingwithSocial

ChatoraLivelyQuestion

AvoidMultitasking

CAREER TIP 163

UseVideoWhenPossible

ManagingDifficultConversations

CASE STUDY 164

EmbraceDifficultConversations

AssumetheBestinOthers

AdoptaLearningStance

StayCalmandOvercomeNoise

FindCommonGround

DisagreeDiplomatically

AvoidExaggerationandEither/OrApproaches

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 167

InitiatetheConversationShareStoriesandFocuson

Solutions

Chapter Wrap-Up 169

A Look Back 169

Key Terms 169

Chapter Review Questions 170

Skill-Building Exercises 170

Endnotes 172

CHAPTER 8

Career Communication 174

GoalSettingandIntentionalityinCareer

Development

TECH TIP 177

ProfessionalNetworking

ConductInformationalInterviews

AttendJobFairsandOtherCareer

NetworkingEvents

AttendCampusSpeechesandOther

ProfessionalDevelopmentEvents

JoinClubsandOtherProfessionalInterestGroups

VolunteerataLocalNonprofit

CAREER TIP 180

PreparingaRésuméandCoverLetter

SetUptheMessageStructurefor

RésumésandCoverLetters

PayAttentiontoToneStyleandDesign

FOCUS ON ETHICS 185

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 187

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xx 01/08/19 07:15 PM

xx CONTENTS

CreateChronologicalandFunctionalRésumés

PreparingRésumésforElectronicScreening

DevelopaReferenceList

ConstructaCoverLetter

PEOPLE FIRST 193

DevelopingYourOnlineProfessionalPersona

ProvideaProfessionalPhoto

CreateaPersonalizedURL

CompletetheSummarySpace

UseMultimedia

ChooseSectionsWisely

ManageYourRecommendationsand

EndorsementsStrategically

BuildaNetworkofImportantConnections

ShowSomePersonalityandBePositive

MaintainaGiverMentality

StayActiveonLinkedIn

Chapter Wrap-Up 199

A Look Back 200

Key Terms 200

Chapter Review Questions 201

Skill-Building Exercises 201

Endnotes 203

CHAPTER 9

Interviewing Successfully 204

PreparingforaSuccessfulInterview

WhatIsanInterview?

TypesofInterviews

ConductingaJobSearch

CAREER TIP 208

DisplayingYourBestSelfduringaJobInterview

TECH TIP 211

PayAttentiontoAppearanceandEtiquette

DistinguishbetweenTypesofQuestions

RespondEffectivelytoInterviewQuestions

FOCUS ON ETHICS 217

PEOPLE FIRST 219

SucceedinWebConferenceInterviews

DoSeveralTrialRuns

MakeSureYourProfileCreatestheRight

Impressions

LookProfessional

TidyYourRoomorOffice

LookDirectlyattheCamera

SmileandExpressYourselfNonverbally

UseNotesStrategically

AvoidDistractions

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 222

FollowingUpaftertheJobInterview

SendingaThankYouNote

ContactingtheInterviewer

Chapter Wrap-Up 224

A Look Back 224

Key Terms 225

Chapter Review Questions 225

Skill-Building Exercises 225

Endnotes 226

CHAPTER 10

Writing across Media 228

CreatingEffectiveEmails

UseEmailfortheRightPurposes

EnsureEaseofReading

ShowRespectforOthers’Time

PEOPLE FIRST 234

ProtectPrivacyandConfidentiality

RespondPromptly

MaintainProfessionalismand

AppropriateFormality

TECH TIP 236

ManageEmotionandMaintainCivility

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 240

WorkingonInternalDigitalPlatforms

FollowYourCompany’sDigital

CommunicationandSocialMediaGuidelines

CAREER TIP 241

OrganizeYourDashboardtoControlYour

CommunicationandInformationFlow

CreateaCompleteandProfessionalProfile

UseBlogsandStatusUpdatesforTeam

Communication

UseSharedFilestoCollaborate

SolveProblemswithDiscussionForums

WritingforExternalAudienceson

SocialMedia

WritingPostsforYourOrganization

WritingPostsforaProfessionalBlog

GeneralGuidelinesforUsing

SocialMediaintheWorkplace

FOCUS ON ETHICS 253

Chapter Wrap-Up 253

A Look Back 254

Key Terms 254

Chapter Review Questions 254

Skill-Building Exercises 255

Endnotes 256

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xxi 01/08/19 07:15 PM

CONTENTS xxi

CHAPTER 11

Major Goals for Presentations 258

KnowtheTypesofProfessionalPresentations

SpeechestoInform

SpeechestoPersuade

SpeechestoIntroduce

GroupPresentations

PEOPLE FIRST 263

SpecialOccasionSpeeches

ChooseanAppropriateTopic

BrainstormtoIdentifyPotentialTopics

IdentifyTopicsThatAreRightforYou

IdentifyTopicsThatAreRightforYourAudience

CAREER TIP 267

IdentifyTopicsThatAreRightfortheOccasion

TECH TIP 268

AnalyzeYourAudience

Age

SexandSexualOrientation

Culture

EconomicStatus

FOCUS ON ETHICS 271

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 272

PhysicalandMentalCapabilities

PoliticalOrientation

ConsidertheSpeakingContext

Purpose

Size

AvailableTime

Distractions

PriorKnowledgeofYourTopic

Chapter Wrap-Up 274

A Look Back 275

Key Terms 275

Chapter Review Questions 275

Skill-Building Exercises 276

Endnotes 277

CHAPTER 12

Planning and Crafting Presentations 278

ArticulateYourPurposeandThesis

DraftaPurposeStatement

CAREER TIP 282

DraftaThesisStatement

FOCUS ON ETHICS 283

OrganizetheBodyofYourSpeech

DetermineYourMainPoints

OrganizeYourMainPointsStrategically

UseSubpointstoSupportYourMainPoints

CreatingaCompelling

IntroductionandConclusion

CraftaMemorableIntroduction

CreateanEffectiveConclusion

PEOPLE FIRST 292

TECH TIP 294

UsingTransitionsEffectively

SomeTransitionsPreviewand

InternallySummarize

SomeTransitionsAreSignposts

SomeTransitionsAreNonverbal

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 296

Chapter Wrap-Up 297

A Look Back 297

Key Terms 297

Chapter Review Questions 298

Skill-Building Exercises 298

Endnotes 299

CHAPTER 13

Finding Support for Your Presentation Goals 300

UnderstandWhereandWhyYouNeedSupport

IdentifyPlacesWhereYouNeedResearchSupport

DeterminetheTypeofSupportYouRequire

EvaluateSupportingMaterial

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 306

KnowWheretoFindInformation

Websites

Books

CAREER TIP 309

PeriodicalsandNonprintMaterials

Databases

PersonalObservations

Surveys

MasteringPresentationAids

PresentationAidsCanEnhanceYourSpeech

LowTechPresentationAids

TECH TIP 314

MultimediaPresentationAids

ChoosingandUsingPresentationAids

UsingSupportingMaterialEthically

CauseNoHarm

Don’tCommitIntellectualTheft

FOCUS ON ETHICS 319

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_fm_i-1.indd xxii 01/08/19 07:15 PM

xxii CONTENTS

PEOPLE FIRST 320

Chapter Wrap-Up 321

A Look Back 321

Key Terms 322

Chapter Review Questions 322

Skill-Building Exercises 322

Endnotes 323

CHAPTER 14

Rehearsing and Delivering Successful

Presentations 324

ChooseYourDeliveryFormat

SomeSpeechesAreImpromptu

SomeSpeechesAreExtemporaneous

SomeSpeechesAreScripted

SomeSpeechesAreMemorized

RecordedSpeeches

RehearsingEffectiveDelivery

VisualElementsAffectDelivery

CAREER TIP 331

THE COMPETENT COMMUNICATOR 333

VocalElementsAffectDelivery

CulturalNormsAffectPreferredDeliveryStyles

ManagingPublicSpeakingAnxiety

PublicSpeakingAnxietyIsaCommonformof

Stress

PEOPLE FIRST 337

PublicSpeakingAnxietyCanBeDebilitating

MakingPublicSpeakingAnxiety

anAdvantage

TECH TIP 340

FOCUS ON ETHICS 341

CreatingPresenceandProjectingConfidence

GetComfortablewithYourAudience

ChooseWordsThatFocusonPeople

StayFlexibleandCalm

UsetheRoomtoYourAdvantage

EngageYourAudience

Chapter Wrap-Up 347

A Look Back 348

Key Terms 348

Chapter Review Questions 348

Skill-Building Exercises 349

Endnotes 351

Glossary 355

Index 363

Design elements: Title page image: ©gobyg/Getty Images

Final PDF to printer

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 100 01/08/19 12:45 PM

LearningObjectives

Afterreadingthischapteryoushould

beabletodothefollowing

LO Illustratehowselectionorganization

andinterpretationoccurduring

perception

LO Explainthereasonswhypeople

commitperceptualerrors

LO Differentiateselfservingbiasand

fundamentalattributionerror

LO Explainhowthenatureofself

conceptispartiallysubjective

LO Describethreepathwaysthrough

whichselfconceptcanshape

communicativebehavior

LO Identifythewaysinwhichimage

managementiscollaborative

involvesthemanagementofmultiple

identitiesandiscomplex

Final PDF to printer

CHAPTER 5

Perspective

Taking

L

izsatinthebreakroomwithCalebaclosecolleague“I’msofrustrated

withAishaWejustmissedourdeadlinewithaclientbecauseshetook

toomuchtimecreatingthegraphicsBythetimeshegavethemtome

IhadonlyonedaytofinishtheupdatestoourwebsiteWithallthemeetings

thatwerescheduledthatdaytherewasnowayformetofinishintimeAisha

simplydoesn’tcarewhenwemissthesedeadlines”

Calebreplied“Don’tworryaboutitIt’snotyourfaultyoualwaysgetthe

jobdoneunlessoneofthegraphicsdesignersdropstheballGraphicsdesign

ersworrymoreaboutgettingawardsthanaboutgivingtheclientswhatthey

want”

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 101 01/08/19 12:45 PM

Final PDF to printer

CHAPTERFIVE PersPective taking

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 102 01/08/19 12:45 PM

We have an ongoing need to make sense of other people. Especially when they act

in ways that are surprising or disappointing—as Aisha did by taking so long to cre-

ate graphics for Liz—our natural tendency is to come up with explanations for their

behaviors. Liz explained Aisha’s behavior by perceiving that Aisha doesn’t care when

deadlines are missed, whereas Caleb perceived that all graphics designers—including

Aisha—are more interested in winning accolades than in pleasing their clients.

We come up with perceptions about other people, and even about ourselves, all

the time. What’s more, many of us assume our perceptions are accurate reflections

of reality, and we communicate on the basis of those perceptions without recogniz-

ing that they may be inaccurate or incomplete. Liz and Caleb may be correct in per-

ceiving that Aisha doesn’t care about their deadlines or their satisfaction with her

work—but they may also be wrong. As we’ll discover in this chapter, our perceptions

of people, including ourselves, are susceptible to a wide range of influences that can

distort their accuracy. Before we act on the basis of our perceptions, therefore, it is

critical to recognize that we don’t always see things the way they are.

HowWePerceiveOthers

Before going on a job interview, applicants may practice introducing themselves, pre-

pare answers to anticipated questions, and consider clothing options to refine their

look. As we’ll discuss later in this book, all these preparations are worthwhile because

they help you put your best self forward. Job candidates may be disappointed, how-

ever, to learn that interviewers often make up their minds about someone within

the first few minutes.

1

Although that may seem too short a period to make a serious

hiring decision, research indicates that people are surprisingly accurate at evaluating

others after very brief periods of time. In fact, some studies have shown that our

impressions and evaluations of others can be more accurate if we have less—rather

than more—information to go on.

2

We form these impressions and evaluations by engaging in perception, the pro-

cess of making meaning from what we experience in the world around us. We notice

physical experiences—such as fatigue, body aches, and congestion—and perceive that

we are ill. We notice environmental experiences—such as cold air, wind, and rain—

and perceive that a storm is under way. When we apply the same process to people,

Final PDF to printer

Inbothpersonaland

professionalsettingswehave

anongoingneedtomake

senseofothers

©XiXinXing/AlamyStockPhoto

How we Perceive otHers

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 103 01/08/19 12:45 PM

we engage in interpersonal perception, which helps us make meaning from our own

and others’ behaviors.

3

As social beings, we are constantly engaged in interpersonal perception. Although

our perceptions may seem to take shape instantaneously, we will find in this section

that they actually form in stages, although quickly. We will also see that several fac-

tors can influence the accuracy of our perceptions, including culture, stereotypes,

primacy and recency effects, and perceptual sets.

PERCEPTIONISAPROCESS

We usually select, organize, and interpret information so quickly and subconsciously

that we think our perceptions are objective, factual reflections of the world. Suppose

you had a conflict this morning with an intern you are training, and throughout

the day he failed to respond to your text messages reminding him to post an update

about your charity donation drive on your organization’s Facebook page. You might

believe he is ignoring you because he is not replying. However, you have created your

perception based on the information you selected for attention (he doesn’t respond),

the way you organized that information (he is angry about your conflict), and the way

you interpreted it (he’s ignoring you).

4

In fact, you might also perceive that he is hav-

ing an extremely busy day or that he left his cell phone in his car. The perception you

form depends on which pieces of information you attend to, how you organize them

in your mind, and how you interpret their meaning.

As Figure 5.1 shows, selection, organization, and interpretation are the three basic

stages of perception. Let’s examine each in turn.

LO

Illustratehowselection

organizationand

interpretationoccurduring

perception

Selection is the first stage. Perception is initiated when one or more of your

senses are stimulated. You hear a customer placing her order in a store. You see a

puppy chewing on an old tennis ball. You smell a co-worker’s cologne. Those sensory

experiences of hearing, seeing, and smelling can prompt you to form perceptions.

Your senses are constantly stimulated by events in your environment, but it’s

impossible to pay attention to all these stimuli at any given moment.

5

Instead, you

engage in selection, the process by which your mind and body help you isolate cer-

tain stimuli to pay attention to. For example, you notice that your officemate left the

lights on all night, but you overlook that he brought you lunch when you were over-

whelmed with work. Clearly, the information we attend to influences the perceptions

we form, although we don’t necessarily make conscious choices about what to ignore.

Selection

Organization

Interpretation

You pay a ention

to a stimulus

You categorize

the stimulus

You determine

what the stimulus

means to you

Final PDF to printer

Figure 5.1

ThreeStagesof

Perception

Perceptionoccursinthree

stagesselectionorganiza

tionandinterpretation

CHAPTERFIVE PersPective taking

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 104 01/08/19 12:45 PM

How, then, does selection occur? Research indicates that three characteristics make a

given stimulus more likely to be selected for attention.

First, being unusual or unexpected makes a stimulus stand out.

6

You might not pay

attention to people talking loudly in a restaurant, but in the library the same loud con-

versation would grab your attention because it is unusual there. Second, repetition or

frequency makes a stimulus stand out.

7

For example, you’re more likely to remember

television commercials you’ve seen repeatedly than those you’ve seen only once. Third,

the intensity of a stimulus affects how much you take notice of it. You are more aware of

strong odors than weak scents, and of bright and flashy colors than dull and muted hues.

8

How do we avoid becoming overwhelmed by so much sensory information? A part of

your brain called the reticular formation serves the important function of helping you focus

on certain stimuli while ignoring others.

9

It is the primary reason why, when having a

conversation with a colleague in a noisy coffee shop, you can focus on what your colleague

is saying and tune out the other sights and sounds bombarding your senses at the time.

Organization is the second stage. Once you have noticed a particular stimulus,

the next step in the perception process is organization, the classification of informa-

tion according to its similarities to and differences from other things you know about.

To classify a stimulus, your mind applies a perceptual schema to it, a mental frame-

work for organizing information into categories we call constructs.

According to communication researcher Peter Andersen, we use four types of

schema to classify information we notice about other people:

10

1. Physical constructs emphasize people’s appearance, causing us to notice objective

characteristics such as height, age, ethnicity, and body shape, as well as subjec-

tive characteristics such as physical attractiveness.

2. Role constructs emphasize people’s social or professional position, so we notice

that a person is a sales rep, an accountant, a stepmother, and so on.

11

3. Interaction constructs emphasize people’s behavior, so we notice that a person is

outgoing, aggressive, shy, or considerate.

4. Psychological constructs emphasize people’s thoughts and feelings, such as anger,

self-assurances, insecurity, or lightheartedness.

Whichever constructs we notice about people—and we may notice more than one

at a time—the process of organization helps us identify how the items we select for

attention are related to one another.

12

If you notice that your human resources direc-

tor is a Little League softball coach and the father of three children, for example,

those two pieces of information go together because they both relate to the roles he

plays. If you notice that he seems irritated or angry, those pieces of information go

together as examples of his psychological state.

Interpretation is the final stage. After noticing and classifying a stimulus, you

have to assign it an interpretation to figure out its meaning for you. Let’s say one of

your co-workers has been especially friendly toward you since last week. She asks

you how your current project is going, and she offers to run errands for you over her

lunch break. Her behavior is definitely noticeable, and you’ve probably classified it as

a psychological construct because it relates to her thoughts and feelings about you.

What is her behavior communicating? How should you interpret it? Is she being

nice because she’s getting ready to ask you for a big favor? Or, is she simply trying to

look good in front of her manager because she is hoping for a promotion?

To address those questions, you likely will pay attention to three factors: your

personal experience, your knowledge of this co-worker, and the closeness of your rela-

tionship with her. First, your personal experience helps you assign meaning to

behavior. If some co-workers have been nice to you in the past just to get favors from

you later, you might be suspicious of this person’s behavior.

13

Second, your knowl-

edge of the person helps you interpret her actions. If you know she’s friendly and

Final PDF to printer

How we Perceive otHers

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 105 01/08/19 12:45 PM

nice to everyone, you might interpret her behavior differently than if you notice she’s

being nice only to you.

14

Finally, the closeness of your relationship influences the way

you interpret a person’s behavior. When your best friend does you an unexpected

favor, you probably interpret it as a sincere sign of friendship. With a co-worker, you

may be more likely to wonder about an ulterior motive.

15

THECIRCULARNATUREOFPERCEPTION

Although perception occurs in stages—selecting, organizing, and interpreting

information—the stages all overlap.

16

Thus, for example, the way we interpret a com-

munication behavior depends on what we notice about it, but what we notice can also

depend on the way we interpret it.

Suppose you are listening to a speech by the regional vice president of your com-

pany. If you like her ideas and proposals, you might interpret her demeanor and

speaking style as examples of her intelligence and confidence. If you oppose her

ideas, however, you might believe her demeanor and speaking style reflect arrogance

or incompetence. Either interpretation, in turn, might lead you to select for attention

only those behaviors or characteristics that support your interpretation and to ignore

those that do not. So, even though perception happens in stages, the stages don’t

always take place in the same order. We’re constantly noticing, organizing, and inter-

preting things around us, including other people’s behaviors.

WECOMMONLYMISPERCEIVEOTHERS’

COMMUNICATIONBEHAVIORS

Although we get a lot of opportunities to practice perception, mistakes are easy to

make. Imagine that during an overseas sales trip, you perceive that two adults you

see in a restaurant are having a heated argument. As it turns out, you later discover

they are not arguing but engaging in behaviors that, in their culture, communicate

interest and involvement.

LO

Explainthereasonswhy

peoplecommitperceptual

errors

Why do we commit such a perceptual error despite our accumulated experience?

The reason is that each of us has multiple lenses through which we perceive the world.

As we’ll see below, those lenses include our cultural and co-cultural backgrounds,

stereotypes, primacy and recency effects, and our perceptual sets. In each case, those

lenses have the potential to influence not only our own communication behaviors but

also our perceptions of the communication of others.

Cultures and co-cultures influence perceptions. One powerful influence on

the accuracy of our perceptions is the culture and co-cultures with which we iden-

tify. Recall from Chapter 2 that culture is

the learned, shared symbols, language, val-

ues, and norms that distinguish one group

of people—such as Russians, South Africans,

or Thais—from another. Co-cultures are

smaller groups of people—such as single par-

ents, bloggers, and history enthusiasts—who

share values, customs, and norms related to

mutual interests or characteristics besides

their national citizenship.

Many characteristics of cultures can influ-

ence our perceptions and interpretations of

other people’s behaviors.

17

For instance, peo-

ple from individualistic cultures frequently

engage in more direct, overt forms of con-

flict communication than do people from

collectivistic cultures. In a conflict, then, an

Cultureisoneofmany

influencesonour

perceptionsofothers

©sjenner/RF

Final PDF to printer

CHAPTERFIVE PersPective taking

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 106 01/08/19 12:45 PM

individualist might perceive a collectivist’s communication behaviors as conveying

weakness, passivity, or a lack of interest. Likewise, the collectivist may perceive the

individualist’s communication patterns as overly aggressive or self-centered, even

though each person is communicating in a way that is normal in his or her culture.

Co-cultural differences can also influence perceptions of communication. Younger

workers might perceive their older supervisors’ advice as outdated or irrelevant,

whereas the supervisors may perceive their younger workers’ indifference to their

advice as naive.

18

Likewise, liberals and conservatives may each see the other’s com-

munication messages as rooted in ignorance.

Stereotypes influence perceptions. A stereotype is a generalization about a

group or category of people that can have a powerful influence on the way we perceive

others and their communication behavior.

19

Stereotyping is a three-part process:

●

First, we identify a group to which we believe another person belongs (“you are

an accountant”).

●

Second, we recall a generalization others often make about the people in that

group (“accountants have no sense of humor”).

●

Finally, we apply that generalization to the person (“therefore, you must have no

sense of humor”).

You can probably think of stereotypes for many groups. What stereotypes come

to mind for people with physical or mental disabilities? Wealthy people? Science

fiction fans? Immigrants? What stereotypes come to mind when you think about

yourself?

Many people find stereotyping distasteful or unethical, particularly when ste-

reotypes have to do with characteristics such as sex, race, and sexual orientation.

20

Unquestionably, because it underestimates the differences among individuals in

a group, stereotyping can lead to inaccurate, even offensive, perceptions of other

people. It may be true, for instance, that women are more emotionally sensitive

than men, but that doesn’t mean every woman is emotionally sensitive. Similarly,

people of Asian descent may often be more studious than those from other ethnic

groups, but not every Asian is a good student, and not all Asians do equally well

in school.

21

Although perceptions based on stereotypes are often inaccurate, they aren’t neces-

sarily so.

22

For example, consider the stereotype that women love taking care of chil-

dren. Not every woman enjoys taking care of children, but some do. Before assuming

your perceptions of others are correct, get to know those people, and let your percep-

tions be guided by what you learn about them as individuals rather than as members

of a group. That advice is especially useful when you find yourself in conflict with

someone you disagree with, as the “People First” box explains.

Primacy and recency effects influence perceptions. As the saying goes, you

get only one chance to make a good first impression. According to a principle called

the primacy effect, first impressions are critical because they set the tone for all

future interactions.

23

Our first impressions of someone’s communication behaviors

seem to stick in our mind more than our second, third, or fourth impressions do. In

an early study of the primacy effect, psychologist Solomon Asch found that a person

described as “intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, and envious” was

evaluated more favorably than one described as “envious, stubborn, critical, impul-

sive, industrious, and intelligent.”

24

Notice that most of those adjectives are negative,

but when the description begins with a positive adjective (intelligent), the effects of

the more negative ones that follow it are diminished.

Asch’s study illustrates that the first information we learn about someone tends to

have a stronger effect on how we perceive that person than information we receive

later.

25

That finding explains why we work so hard to communicate competently

during a job interview, on a date, or in other important situations. When people

Final PDF to printer

How we Perceive otHers

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 107 01/08/19 12:45 PM

Final PDF to printer

PEOPLE FIRST

Being Aware of Stereotypes

IMAGINETHISWhileonyourbreakatworkyouandyour

colleagueKarinaarediscussingyourcompanypresident’s

recentpublicstatementaboutimmigrationKarina’scom

mentsleadyoutorealizethatyouhavestronglyopposing

opinionsOneofyoufeelsundocumentedworkerswaste

taxpayers’moneybyusing social serviceswithout

defrayingtheircostTheotherbelievesevery

one deserves to share in the “American

dream”andthatsomeUSindustriessuch

as agriculture and construction employ

largenumbersofundocumentedworkers

YoufindKarina’sopinionsinfuriating

andwonderaloudhowshecanpossibly

thinkthewayshedoesShewondersthe

sameaboutyouandsoonyourconversa

tionhasturnedintoanargumentwitheach

ofyoucallingtheother’sbeliefsignorantanddan

gerousYoubothgobacktoworkangryandfrustrated

NowconsiderthisYourconflictwithKarinawasbased

partly on your differing opinions about immigration

Howeveritlikelywasalsoinfluencedbyyourperceptions

ofeachotherInparticularonceyourealizedthediffer

enceinyourpositionsyoumayhavestereotypedeach

otheras“conservative”or“liberal”Doingsomayhaveled

youtomakeinaccurateassumptionsabouttheotherand

to consider yourself openminded while dismissing the

otherperson’sargumentsasuninformed

● Thefirststepinkeepingstereotypesfrominfluenc

ingyourperceptionsisawarenessBecauseKarina’s

positiondiffersfromyoursdoyouassumesheis

narrowmindedornaive?Doyoupresupposeany

thingaboutherbackgroundorexperiences?

● Ifyoudorecognizeassumptionsyouaremaking

aboutKarinaremindyourselfthatstereotypes

areofteninaccuratewhenappliedtoindividuals

Itmaybetruethatpeoplewithliberalandconser

vativeviewpointshavedifferentbackgrounds

andlifeexperiencesbutthatdoesn’t

necessarilymeaneveryconservative

personisthesamenoreveryliberal

person

● InsteadofdismissingKarina’sargu

mentsaswrongaskherwhyshefeelsas

shedoesandlistentoheranswerwith

anopenmindYoumayfindherpositions

wellinformedandlogicalevenifyoudis

agreewiththem

Stereotypescan easily influence our perceptions of

othersevenwithoutourbeingawareItleadsustothink

superficiallyaboutothersandtheirideaswhichcanmake

itdifficultforustoprioritizepeopleabovethedisagree

mentswemayhavewiththem

THINKABOUTTHIS

Whydoyouthinkstereotyping issoeasytodo

and so challenging to combat? W

hen haveyour

stereotypesaboutotherindividualsturnedoutto

beinaccurateinthepast?

evaluate us favorably at first, they are more likely to perceive us in a positive light

from then on.

26

Stand-up comedians will tell you, however, that the two most important jokes in a

show are the first and the last. That advice follows a principle known as the recency

effect, which says that the most recent impression we have of a person’s communica-

tion is more powerful than our earlier impressions.

27

Which is more important, the first or the most recent impression? The answer is

that both appear to be more important than any impressions we form in between.

28

To

grasp this key point, consider the last significant conversation you had with someone.

You probably have a better recollection of how the conversation started and ended

than you do of what was communicated in between. Figure 5.2 illustrates the relation-

ship between the primacy effect and the recency effect by showing how our first and

most recent impressions of people overshadow our other perceptions of them.

Perceptual sets influence perceptions. “I’ll believe it when I see it,” people

often say. However, our perception of reality is influenced by more than what we see.

CHAPTERFIVE PersPective taking

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 108 01/08/19 12:45 PM

Stereotypingcanbeeasyto

dobutperceptionsformed

onthebasisofstereotypes

areofteninaccurateWhat

stereotypescometomind

whenyouseethepeoplein

thesephotos?

Top©AndreaDeMartin/RF

bottomleft©tixti/RF

bottomright

©jenjen/Getty

Images

Our biases, expectations, and desires can create what psychologists call a perceptual

set, or a predisposition to perceive only what we want or expect to perceive.

29

An

equally valid motto might therefore be “I’ll see it when I believe it.”

For example, our perceptual set regarding gender guides the way we perceive and

interact with newborns. Without the help of a contextual cue such as blue or pink

baby clothes, we sometimes have a hard time telling whether a dressed infant is male

or female. However, research shows that if we’re told an infant’s name is David, we

perceive that child to be stronger and bigger than if the same infant is called, say,

Diana.

30

Our perceptual set tells us that male infants are usually bigger and stronger

than female ones, so we “see” a bigger, stronger baby when we’re told it’s a boy. Our

perceptions can then affect our communication behavior: we may also hold and talk

to the “female” baby in softer, quieter ways than we do with the “male” baby.

Our perceptual set also influences how we make sense of people, circumstances,

and events. Deeply religious individuals may talk about healings as miracles or

answers to prayer, whereas others may describe them as natural responses to medica-

tion.

31

Highly homophobic people are more likely than others to perceive affectionate

communication between men as sexual in nature.

32

Final PDF to printer

communicating and exPlaining our PercePtions

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 109 01/08/19 12:45 PM

CAREER TIP

M

any people recognizeAndre Iguodala as a star pro

fessional basketball player who has contributed to

multipleNBA championships Fewer people mayknow of

hisotherprofessionalaccomplishmentsasasuccessfultech

venturecapitalist and soughtafterspeakerabout leader

shipandtechnology

Iguodalahas overcome many stereotypes and misper

ceptionsaboutathletesandtheiraptitudeforbusinessven

turesAsheexplained“ItrytoletthepeopleIdobusiness

withoffthecourtknowthatI’mseriousaboutmybusiness

offthecourtSoItrynottomixthetwoIwantthemto

knowthatI’mseriousaboutwhatI’mdoingandit’sapriority

tome”

Iguodala has overcome the primacy effect most peo

ple’sfirstimpressionsofhimareasabasketballplayerto

demonstrate his talent for business He networks among

insiders in the tech industry He spends hours each day

learningaboutthelatesttrendsinbusinessandtechnology

Hegrillspotentialbusinesspartnersanddemonstrateshis

thoroughbackgroundinthetechindustryHeactivelyseeks

out speaking opportunities at technology events and has

gainedareputationasaninnovativethinkerandleader

Iguodala’sawarenessof the wayhe maybeperceived

has helped him intentionally develop his skills and com

municateinwaysthatmakealastingimpressionbasedon

Final PDF to printer

AndreIguodala

©DrewAltizer/SipaPress/SanFrancisco/CA/UnitedStates

his most recent encounters in business recency effect

Identify the misperceptions others may have of you and

thenlookforopportunitiestochallengethosemispercep

tionsIfyoubelieveothersseeyouaslackinginitiativefor

instancevolunteertoleadaworkteamororganizeanafter

worksocialeventIfothersperceivethatyou’renotateam

playermakeapointtoaskcoworkersfortheirinputona

projectorinvitethemtobrainstormwithyouonaproblem

LikeIguodalayoucanthenfindwaystoreinventyourselfas

yourcareerinterestschangeorexpand

Perception is a complex process. As we will

discover in the next section, we are vulnerable to

mistakes not only when we form perceptions but

also when we try to explain what we perceive.

Communicatingand

ExplainingOurPerceptions

Suppose you’re meeting with a committee at work

that is focused on restructuring the employee

evaluation process. In the middle of your discus-

sion, your supervisor enters the room, walks over

to your co-worker Erika, and whispers something

to her. Erika’s eyes start to water immediately, and

then she gets up from the table and follows your

supervisor out of the room. The rest of you stare

at each other, wondering what just happened. Did

Erika just receive some upsetting news? Was she

tearing up because she was happy about what

your supervisor told her?

Figure 5.2

PrimacyandRecencyEffects

Ourfirstimpressionsandourmostrecentimpressionsaremore

importantthanthosethatcomeinbetween

First

Second Third Fourth ecent

CHAPTERFIVE PersPective taking

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 110 01/08/19 12:45 PM

When we perceive social behavior, especially behavior we find surprising, our

nearly automatic reaction is to try to make sense of it.

35

We need to understand what

is happening to know how to react. After all, if you perceive that someone is commu-

nicating out of anger or jealousy, you will react differently than if you perceive the

motivation is humor or sarcasm. Our ability to explain social behavior—including our

own—helps us perceive our social world. In this section, we will see that we explain

behaviors by forming attributions for them, and we will discover how to avoid two of

the most common errors people make when doing so.

WEEXPLAINBEHAVIORTHROUGHATTRIBUTIONS

An attribution is an explanation of an observed behavior, the answer to the question

“Why did this occur?”

36

Attributions tend to vary along three important dimensions:

locus, stability, and controllability.

37

Attributions vary in locus. Locus describes the place where the cause of a behav-

ior is “located,” whether within or outside ourselves.

38

Some of our behaviors have

internal loci (the plural of locus), meaning they’re caused by a particular characteristic

of ourselves. Other behaviors have external loci, meaning they are caused by some-

thing outside ourselves. If your boss is late for your 9 a.m. performance review, an

internal attribution you might make about her is that she has lost track of time or

she’s making you wait on purpose. In other words, it is something about her that is

making her late. An external attribution is that the traffic is heavy or an earlier meet-

ing she is attending has run long.

Attributions vary in stability. A second dimension of attributions is whether the

cause of a behavior is stable or unstable.

39

A stable cause is one that is permanent,

semipermanent, or at least not easily changed. Why was your boss late? Rush hour

traffic is a stable cause for lateness because it’s a permanent feature of many peo-

ple’s morning commute. The attribution that she is rarely punctual would likewise

be stable because it identifies an enduring aspect of her behavior. In contrast, a traf-

fic accident or an overly long morning meeting would be an unstable cause of your

boss’s lateness because those events occur only from time to time and are largely

unpredictable.

SHARPEN YOUR SKILLS

Attribution Making

WorkingwithapartnerorinasmallgroupconsiderErika’sreac

tion to what your manager told her and generate an attribu

tionforherreactionthatisinternalandstableThengenerate

anattributionthatisexternalandunstableFinallygeneratean

attributionthatisinternalandunstableTakenoteofwhichattri

butionsareeasiertogeneratethanothers

Attributions vary in controllability.

Finally, causes for behavior vary in how

controllable they are.

40

You make a con-

trollable attribution for someone’s behavior

when you believe the cause was under that

person’s control. In contrast, an uncontrol-

lable attribution identifies a cause beyond

the person’s control. If you perceive that

your boss is late for your appointment

because she has spent too much time

socializing with other co-workers before-

hand, that is a controllable attribution

because socializing is under her control.

Alternatively, if you perceive she’s late because she was in a car accident on the way

to work, that is an uncontrollable attribution because she couldn’t help but be late if

she wrecked her car.

LO

Differentiateselfservingbias

andfundamentalattribution

error

Final PDF to printer

AVOIDINGTWOCOMMONATTRIBUTIONERRORS

Although most of us probably try to generate accurate attributions for other people’s

behaviors, we are still vulnerable to making attribution mistakes.

41

Suppose you have

communicating and exPlaining our PercePtions

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 111 01/08/19 12:45 PM

worked at a restaurant for many years. You started out bussing tables, then became

a server, and you’re now the weekend manager. You have been a loyal employee to

the restaurant’s owner, Olivia, even accepting reduced hours when business has been

slow. Thus, you are shocked to learn that Olivia is selling the restaurant and moving

out of state. After many years of loyalty, you feel betrayed at her decision and uncer-

tain about the future of your own job. You conclude that Olivia is being greedy and

thinking only of herself. You learn later, however, that she decided to sell her business

and move in order to provide care for her elderly father after his diagnosis of dementia.

We’re all prone to taking mental shortcuts when generating attributions. As a

result, our attributions are often less accurate than they should be. Two of the most

common attribution errors—which we can better avoid if we understand them—are

the self-serving bias and the fundamental attribution error.

Be aware of the self-serving bias. The self-serving bias is our tendency to attri-

bute our successes to stable, internal causes and our failures to unstable, external

causes.

42

For instance, if you gave a successful sales presentation to a potential client,

you may say it was great because you were well prepared, but if it went poorly, you

might say the noise in the room was distracting you. Such attributions are self-serving

because they suggest that our successes are deserved but our failures are not our fault.

Although the self-serving bias deals primarily with attributions we make for our

own behaviors, research shows that we often extend this tendency to important peo-

ple in our lives.

43

In a satisfying relationship, for instance, people tend to attribute

their partner’s positive behaviors to internal causes (“She remembered my birthday

because she’s thoughtful”) and negative behaviors to external causes (“He forgot my

birthday because he’s been very preoccupied at work”). In a distressed relationship,

the reverse is often true: people attribute negative behaviors to internal causes (“She

forgot my birthday because she’s completely self-absorbed”) and positive behaviors

to external causes (“He remembered my birthday only because I reminded him

five times”).

Avoid the fundamental attribution error. How did you react the last time

someone cut you off in traffic? Did you think, “He must be late for something import-

ant” or “What a jerk”?

It is a human tendency to commit the fundamental attribution error, in which we

attribute other people’s behaviors to internal rather than external causes.

44

But bear in

mind that people’s behaviors—including your own—are

often responses to external forces. For instance, when a

new doctor spends only three minutes with you before

moving on to the next patient, you might perceive that

she’s not very caring. That would be an internal attribu-

tion for her communication behavior, which the funda-

mental attribution error makes more likely. To judge the

merits of that attribution, however, ask yourself what

external forces might have motivated the doctor’s behav-

ior. Maybe another doctor’s absence that day left her

with twice as many patients as usual. Good communica-

tors recognize the tendency to form internal attributions

for people’s behaviors, and they force themselves to con-

sider external causes that might also be influential.

We do make accurate attributions for people’s

behaviors (including our own). But the self-serving

bias and the fundamental attribution error are easy

mistakes to commit. The more we know about them,

the more often we can base our communication behav-

iors on accurate perceptions of ourselves and others.

Theselfservingbiasleads

manyofustobelieveour

successesaredeservedbut

ourfailuresarenotourfault

©DeanDrobot/RF

Final PDF to printer

CHAPTERFIVE PersPective taking

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 112 01/08/19 12:45 PM

HowWePerceiveOurselves

As much as your communication’s effectiveness depends on your ability to perceive

others, it also depends on your ability to perceive yourself. In this section, we will dis-

cover that each of us perceives our self through our self-concept, and we will examine

the characteristics of a self-concept. We will also learn how self-concept influences

communication behavior and relates to self-esteem.

LO

Explainhowthenatureofself

conceptispartiallysubjective

SELFCONCEPTDEFINED

Let’s say you are asked to come up with ten ways to answer the question “Who am I?”

What words will you pick? Which answers are most important? Each of us has a set

of ideas about who we are that isn’t influenced by moment-to-moment events (such as

“I’m happy right now”) but is fairly stable over the course of our lives (such as “I’m a

happy person”). Your self-concept, also called your identity, is composed of your own

stable perceptions about who you are. As we’ll see in this section, self-concepts are

multifaceted and partly subjective.

Self-concept is multifaceted. We define ourselves in many different ways. Some

of these ways rely on our name: “I’m Sunita” or “I’m Darren.” Some rely on physical

or social categories: “I am a vegan” or “I am Australian.” Others make use of our skills

or interests: “I’m artistic” or “I’m good with numbers.” Still others are based on our

relationships to other people: “I am an uncle” or “I do volunteer work with homeless

children.” Finally, some rely on our evaluations of ourselves: “I am honest” or “I am

impatient.” You can probably think of several other ways to describe who you are.

Which of those descriptions is the real you?

The answer is that your self-concept has several different parts, and each of your

descriptions taps into one or more of those parts. What we call the self is a collection

of smaller selves. If you’re female, that’s a part of who you are, but it isn’t everything

you are. Asian, athletic, agnostic, or asthmatic may all

be parts of your self-concept, but none of those terms

defines you completely. All the different ways you would

describe yourself are pieces of your overall self-concept.

One way to think about your self-concept is to dis-

tinguish between aspects of yourself that are known to

others and aspects that are known only to you. In 1955,

U.S. psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham cre-

ated the Johari window, a visual representation of the

self as composed of four separate parts.

45

According to

this model, which is illustrated in Figure 5.3:

Figure 5.3

JohariWindow

TheJohariwindowconsistsofopenblindhiddenand

unknownquadrantseachrepresentingadifferentcombi

nationofwhatisknowntousandwhatisknowntoothers

aboutus

Known to Others

Unknown to Others

Known to Self

Unknown to Self

BLINDOPEN

What others know

about you, but you

don’t recognize in yourself.

What you know,

and choose to reveal

to others, about yourself.

HIDDEN

What you know

about yourself, but

choose not to reveal.

UNKNOWN

The dimensions

of yourself that no

one knows.

●

The open area consists of characteristics known

both to the self and to others. Those proba-

bly include your name, sex, hobbies, academic

major, and other aspects of your self-concept that

you are aware of and freely share with others.

●

The hidden area consists of characteristics that

you know about yourself but choose not to reveal

to others, such as emotional insecurities or trau-

mas from your past that you elect to keep hidden.

●

The blind area refers to aspects of ourselves that

others see in us, but of which we are unaware.

For instance, others might see us as impatient or

moody even if we don’t recognize these traits in

ourselves.

Final PDF to printer

How we Perceive ourselves

flo14498_ch05_100-125.indd 113 01/08/19 12:45 PM

●

Finally, the unknown area comprises aspects of our self-concept that are not

known either to us or to others. For example, no one—including you—knows

what kind of parent you will be until you actually become one.

If you think about people who are important to you professionally or personally,

you can construct a different Johari window that reflects your self-concept with each

of those people. Perhaps you share more about yourself with some people than with

others, making your open pane larger and your hidden pane smaller in those relation-

ships. Some people may know certain details about you that you don’t recognize in

yourself (your blind pane), whereas others do not. The point is that our self-concept

can differ with different people in our lives.

Self-concept is partly subjective. Some of what we know about ourselves is based

on objective facts. Suppose, for instance, that you are 5’8” tall, have brown hair, and

were born in San Francisco but now live in Dallas. Those aspects of your self- concept

are objective—they are based on fact and not on someone’s opinion. That doesn’t mean

you have no choice about them. You might have chosen to move to Dallas to attend

school or take a great job, and although you were born with brown hair, you could

change your hair color if you wanted to. Referring to those personal characteristics as

“objective” simply means that they are factually true. Many aspects of our self-concept

are subjective rather than objective, however. “Subjective” means that they are based

on the impressions we have of ourselves rather than on objective facts.