Journal of Family Psychology

1996,

Vol. 10, No. 3, 243-268

Copyright 1996 by the American Psychological Association, Inc.

O893-32O0/9OT3.OO

Parental Meta-Emotion Philosophy and the Emotional Life

of Families: Theoretical Models and Preliminary Data

John M. Gottman, Lynn Fainsilber Katz, and Carole Hooven

University of Washington

This article introduces the concepts of parental meta-emotion, which refers to parents'

emotions about their own and their children's emotions, and meta-emotion philosophy,

which refers to an organized set of thoughts and metaphors, a philosophy, and an

approach to one's own emotions and to one's children's emotions. In the context of a

longitudinal study beginning when the children were 5 years old and ending when they

were 8 years old, a theoretical model and path analytic models are presented that relate

parental meta-emotion philosophy to parenting, to child regulatory physiology, to

emotion regulation abilities in the child, and to child outcomes in middle childhood.

The importance of parenting practices for

children's long-term psychological adjustment

has been a central tenet in developmental and

family psychology. In this article, we introduce

a new concept of parenting that we call parental

meta-emotion philosophy, which refers to an

organized set of feelings and thoughts about

one's own emotions and one's children's emo-

tions.

We use the term meta-emotion broadly to

encompass both feelings and thoughts about

emotion, rather than in the more narrow sense

of one's feelings about feelings (e.g., feeling

guilty about being angry). The notion we have

in mind parallels metacognition, which refers to

the executive functions of cognition (Allen &

Armour, 1993; Bvinelli, 1993; Flavell, 1979;

Fodor, 1992; Olson & Astington, 1993). In an

analogous manner, meta-emotion philosophy

John M. Gottman, Lynn Fainsilber Katz, and Car-

ole Hooven, Department of Psychology, University

of Washington.

The research of this article was supported by Na-

tional Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research

Grants MH42484 and MH35997, by an NIMH Merit

Award to extend research in time, and by Research

Scientist Award K2MH00257.

This research received a great deal of support from

Michael Guralnick, director of the Center for Human

Developmental Disabilities (CHDD), and CHDD's

core facilities, particularly the Instrument Develop-

ment Laboratory at the University of Washington.

Correspondence concerning this article should be

addressed to John M. Gottman, Department of Psy-

chology, Box 351525, University of Washington,

Seattle, Washington 98115.

refers to executive functions of emotion. In this

article, we discuss the evolution of the meta-

emotion construct and describe its relationship

to various aspects of family and child function-

ing. We present a parsimonious theoretical

model of the role of parental meta-emotions in

children's emotional development, operational-

ize this model, and present some path analytic

tests of the model. In this model, we argue (a)

that parental meta-emotion philosophy is re-

lated to both the inhibition of parental negative

affect and the facilitation of positive parenting;

(b) that it directly affects children's regulatory

physiology; and (c) that this, in turn, affects

children's ability to regulate their emotions—

hence, parental meta-emotion philosophy has an

impact on a variety of child outcomes.

Background

The Concept of Meta-Emotion

Research in developmental psychology on the

effects of parenting has focused on parental

affect and discipline, selecting variables such as

warmth, control, authoritarian or authoritative

styles,

and responsiveness (see Ainsworth, Bell,

& Stayton, 1971; Baumrind, 1967, 1971;

Becker, 1964; Cohn, Cowan, Cowan, & Pear-

son, 1992; C. P. Cowan & P. A. Cowan, 1992;

Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Patterson, 1982; and

Schaefer, 1959). Little attention has been placed

on examining the parents' feelings and cogni-

tions about their own affect or their feelings and

cognitions about their child's affect.

243

244 GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

Our review of popular parenting guides also

revealed that the overwhelming majority of

these parenting guides are based on obtaining

and maintaining child discipline. However, one

genre of parenting guides focuses on children's

emotions and on how to make immediate and

everyday emotional connections with a child

that are not critical and contemptuous, but ac-

cepting. These kinds of parenting guides can be

traced to the seminal influence of one child

psychologist: Haim Ginott (Ginott, 1956, 1971,

1975).

Although many psychological systems

of thought (e.g., attachment theory, psychoanal-

ysis) have written about the importance of the

child's affect, Redl (1966) and Ginott both em-

phasized intervening with a child's strong neg-

ative emotions while the child is having the

emotions. They also emphasized intervening di-

rectly, dealing with the child's conscious

thoughts and actions. This difference was so

important, in our view, that it amounted to a

revolution in "how one deals with children," to

use Redl's (1966) words.

Our initial interest was in this concept of

parents' awareness of their children's emotional

lives and their attempts to make emotional con-

nections with their children. This interest led to

the development of our meta-emotion interview

(Katz & Gottman, 1986). All the parents were

separately interviewed about their own experi-

ence of sadness and anger, their philosophy

of emotional expression and control, and their

attitudes and behavior about their children's

anger and sadness. In our pilot work, we dis-

covered a great variety in the emotions, experi-

ences,

philosophies, and attitudes that parents

had about their own emotions and the emotions

of their children. For example, one pair of par-

ents said that they viewed anger as "from the

devil," and that they would not permit them-

selves or their children to express anger. Some

parents were accepting of sadness and anger but

did not engage in problem solving with their

child. Other parents were not disapproving of

anger but, instead, in laissez-fairre fashion, ig-

nored anger in their children. Still other parents

encouraged the expression and exploration of

anger. There was similar variation with respect

to sadness. Some parents minimized sadness in

themselves and in their children, saying such

things as, "I can't afford to be sad," or "What

does a child have to be sad about?" Other par-

ents thought that emotions like sadness in their

children were opportunities for intimacy, that

sadness was important information that some-

thing was missing in one's life.

This area of meta-emotion is probably char-

acterized by great variability even in laboratory

experiments that elicit emotions. Researchers

have reported large variability in results from

laboratory experiments designed to elicit emo-

tion, such as the startle response. Ekman,

Friesen, and Simons (1985) reported a consis-

tent set of responses across participants to being

startled, but there were huge individual differ-

ences in the emotional response to having been

startled, that is, in people's meta-emotions to

the startle; Levenson and Sutton (personal com-

munication, June 15, 1994) reported a similar

set of

results.

Meta-emotion may be a pervasive

and understudied dimension in emotion re-

search.

An Emotion-Coaching Meta-Emotion

Philosophy

In our pilot work, we noticed that there are

some parents who are aware of the emotions in

their lives (particularly the negative emotions),

who can talk about those emotions in a differ-

entiated manner, who are aware of these emo-

tions in their children, and who assist their

children with their emotions of anger and sad-

ness,

acting like an emotion coach. This is a

parental meta-emotion philosophy we call an

emotion-coaching philosophy. We found that an

emotion-coaching meta-emotion philosophy

had five components: parents (a) said that they

were aware of low intensity emotions in them-

selves and in their children; (b) viewed the

child's negative emotion as an opportunity for

intimacy or teaching; (c) validated their child's

emotion; (d) assisted the child in verbally label-

ing the child's emotions; and (e) problem solved

with the child, setting behavioral limits, and

discussing goals and strategies for dealing with

the situation that led to the negative emotion.

We hypothesized that these parents have a

greater ability than other parents to maneuver in

the world of emotions, that they are more com-

fortable with the world of emotions, and that

they are better able to regulate emotions. We

expected them to be more affectionate with their

children and less autocratic than other parents.

However, it was our observation that an

emotion-coaching meta-emotion philosophy

was different from parental warmth, and we

META-EMOTION

245

tested this notion

in the

current study. Very

concerned, generally positive

and

warm parents

can

be

oblivious

to the

world

of

emotion,

and an

emotion-coaching meta-emotion philosophy

is

something additional that these parents bring

to

their roles

as

parents. Perhaps warmth

and

limit

setting

are

correlated with these meta-emotion

variables,

but we

think that they

are not the

same dimensions

of

parenting.

In contrast,

we

found that

a

dismissing meta-

emotion philosophy

was one in

which parents

felt that

the

child's sadness

or

anger were

po-

tentially harmful

to the

child, that

it was the

parents'

job to

change these toxic negative emo-

tions

as

quickly

as

possible, that

the

child

needed

to

realize that these negative emotions

would

not

last

and

were

not

very important,

and

that

it

was

the

parent's job

to

convey

to the

child

a sense that

he or she

could ride

out

these

negative emotions without damage.

We

found

that emotion-dismissing families could

be sen-

sitive

to

their children's feelings

and

wanted

to

be helpful,

but

their approach

to

sadness,

for

example,

was to

ignore

or

deny

it as

much

as

possible. Often they perceived

a

child's strong

emotion

as a

demand that they

fix

everything

and make

it

better. These parents hoped that

the

dismissing strategy would make

the

emotion

go

away quickly. They often conveyed

a

sense that

the child's emotion

was

something they

may

have been forced

to

deal with,

but it was not

interesting

or

worthy

of

attention

in itself.

They

described sadness

as

something

to get

over, ride

out,

but

look beyond

and not

dwell

on.

They

often used distractions when their child

was sad

to move

the

child along,

and

they even used

comfort,

but

within specified time limits,

as if

they were impatient with

the

negative emotion

itself.

They preferred

a

happy child

and

often

found these negative states

in

their child quite

painful. They

did not

present

an

insightful

de-

scription

of

their child's emotional experience

and

did not

help

the

child with problem solving.

They

did not see the

emotion

as

beneficial

or as

any kind

of

opportunity, either

for

intimacy

or

for teaching. Many dismissing families

saw

their child's anger (without misbehavior)

as

enough cause

for

punishment

or a

Time

Out.

It

is

important

to

point

out

that

the

term

meta-emotion

is

being used

in its

broadest

sense. Metacommunication

is

communication

about communication,

and

metacognition

is

cognition about cognition. Meta-emotion

in the

narrow sense might refer

to

emotions about

emotion;

for

example,

we

might only

be

study-

ing

how

parents feel about getting angry

at

their

children (e.g., feel guilty about getting angry).

However,

we use the

term broadly

to

encom-

pass feelings

and

thoughts about emotion.

As

the examples just provided suggest,

the con-

struct being tapped involves parents' feelings

and thoughts about their

own and

their chil-

dren's emotions, their responses

to

their child's

emotions,

and

their reasoning about these

re-

sponses (i.e., what

the

parent

is

trying

to

teach

the child when responding

to the

child's anger).

This broader construct indexes

a

fundamental

attitude

or

approach

to

emotion.

For

some

peo-

ple,

emotions

are a

welcome

and

enriching part

of their lives; they believe,

in a

fundamental

way, that

it is OK to

have feelings. However,

for other people, emotions

are to be

avoided

and

minimized;

the

world

of

negative emotions

is

seen

as

dangerous

(see

Appendix).

Meta-Emotion

and

Parenting

From

a

theoretical standpoint,

we

think

our

measures

of

parental meta-emotion philosophy

are embedded within

a web of

measures that

tap

parent-child interaction.

We

expect that

par-

ents'

meta-emotion philosophy

is not

indepen-

dent

of

their parenting. Hence,

in our

theoretical

model,

we

include meta-emotion variables

along with parenting variables.

It is our

view

that

we

need

to be

specific about

our

description

of parenting;

for

heuristic purposes (within

the

restricted range

of

families

in our

samples),

we

discuss three dimensions

of

parenting behav-

iors.

First,

we

started with everyday, mundane

negativity. Inherent

in the

literature

on

parent-

ing

is the

idea that small things

in

everyday

parenting

can be

quite harmful

for

children

(or

serve

as

indexes

of

more harmful types

of par-

enting), akin

to

what

J.

Reid

has

called "natter-

ing"

(see

Patterson, 1982). Ginott (1965) wrote

strongly about this

in his

discussion

of the im-

portance

of

(a) understanding

and

validating

the

child's emotions

and (b)

avoiding contempt

and

disapproval. Thus,

in our

measurement

of

this

negativity

in our

laboratory-based parent-child

interactions,

we

included three variables: paren-

tal intrusiveness, criticism,

and

mockery.

We

call this type

of

parenting derogatory.

In a

teaching task,

as

some

of the

parents

in our

laboratory instructed their children, they mixed

246

GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

in a blend of frustration, taking over for the

child as soon as the child had trouble with the

task (which we call intrusiveness), using criti-

cism and derisive humor (mockery, humiliation,

belittlement of the child). We think that this

dimension of parenting represents the microso-

cial processes characteristic of parental rejec-

tion (e.g., Whitbeck, Hoyt, Simons, & Conger,

1992).

Next, we also wished to measure two kinds of

positive parenting. The first is the kind of

warmth that Baumrind (1967, 1971) and others

described: We refer to this dimension of posi-

tive parenting as warmth. Following C. P.

Cowan and P. A. Cowan (1992), we include in

this dimension of warmth co-warmth, which

includes warmth between parents while inter-

acting with the child. Our second dimension of

positive parenting involves a positive structur-

ing, responsive, enthusiastic, engaged, and af-

fectionate parenting during the teaching task in

our laboratory. This type of positive parental

response goes beyond warmth. It includes the

responsive style that attachment theorists have

identified, but it is more complex than that. We

call it scaffolding-praising (on the general

scaf-

folding concept, see Choi, 1993; Kirchner,

1991;

Pratt, Kerig, Cowan, & Cowan, 1988; and

Vygotsky, 1987). From watching and coding

the videotapes, we noticed that this is a dimen-

sion quite different from Baumrind's authorita-

tive parenting. Parents high on the scaffolding-

praising dimension provided structure for the

task, stating the goals and procedures of the

game simply, in a relaxed manner, and with low

information density; they then waited for their

child to act and commented primarily when the

child did something right, acting like a cheering

section at a football game, giving praise and

approval. Parents low on this scaffolding-prais-

ing dimension either provided little structure for

the learning situation for their children, or they

gave information rapidly, with high density, and

enthusiastically, appearing to excite and con-

fuse the child; such parents then waited to com-

ment until their child had made a mistake.

These parents were then usually critical of the

child's performance.

Are the concepts of meta-emotion and emo-

tion coaching simply subdimensions of positive

parenting? We think not; we think that they add

to current concepts in the parenting literature

and are more general. Emotion coaching is one

reason why the parenting advice literature is, in

our view, far richer than the parenting research

literature. For example, what would we predict

that an authoritative parent would do (or rec-

ommend that he or she should do) when his or

her child has just had a nightmare? Being warm

and structuring provides no real guidelines.

Emotion coaching does provide these guide-

lines.

What is the expected relationship between

meta-emotion and the derogation, warmth, and

scaffolding-praising dimensions? When we be-

gan this study, we had two working hypotheses.

The first hypothesis was that a coaching meta-

emotion philosophy might be nested within a

web of positive parenting. We proposed that an

emotion-coaching meta-emotion philosophy en-

tails parenting that goes a step beyond the idea

of warmth; that is, we suggested that it entails

scaffolding-praising parenting. The second hy-

pothesis was that meta-emotion performs its

major function by inhibiting parental deroga-

tion; in particular, as Ginott (1965) noted, we

proposed that understanding and validating the

child's emotions serves to avoid criticism, con-

tempt, and disapproval of the child. Most of the

examples from Ginott's books had to do with

the importance of emotion coaching in avoiding

escalating negativity, frustration, disapproval,

and emotional distance between parents and

children. It appears to have been first suggested

foremost as a mechanism for obtaining exten-

sive relief from spiraling negativity: Perhaps

validating the child's affect serves as an oppo-

nent process to derogation. Hence, it was en-

tirely reasonable to hypothesize that the major

effect of a coaching meta-emotion philosophy

would be inhibiting parental negativity and that

it might have no effect on positive parenting.

Meta-Emotion and the Development of

Emotion Regulation Abilities

Precisely how do we think that meta-

emotions affect the functioning of families and

act to affect child outcomes? What do we pro-

pose as the mechanism? We are particularly

drawn to theories that attempt to integrate be-

havior and physiology, and our theorizing is

oriented toward approaches that have empha-

sized the importance of (a) the development of

children's abilities in the regulation of emotion

(Garber & Dodge, 1991) and (b) the develop-

ment of children's abilities to self-soothe strong

META-EMOTION

247

and potentially disruptive emotional states

(Dunn, 1977), focus attention, and organize

themselves for coordinated action in the service

of some goal. We think that these general sets of

abilities underlie the development of other com-

petencies. We are especially interested in chil-

dren's peer social skills, particularly because of

their predictive validity (Parker & Asher, 1987).

Central peer social competencies include the

ability to resolve conflict, to find a sustained

common ground play activity, to compromise in

play, and to empathize with a peer in distress

(e.g., see Asher & Coie, 1990; Gottman, 1983;

Gottman & Parker, 1986).

We suggest that fundamental to these abilities

is the ability to soothe one's self physiologically

and to focus attention. These abilities underlie

being able to listen to what one's playmate is

saying, being able to take another's role and

empathize, and being able to engage in social

problem solving. They involve the child know-

ing something about the world of emotion, both

his or her own and others'. We propose that this

knowledge arises only out of emotional connec-

tion being important in the home. In the follow-

ing section, we briefly review our reasons for

measuring child physiology as related to the

construct of emotion regulation.

Regulatory Physiology

1

We used Porges' (1984) suggestion that there

may be a physiological basis for the ability to

regulate emotion. To explain his notions, we

discuss two concepts related to the child's para-

sympathetic nervous system (PNS) physiology.

The major nerve of the PNS is called the vagus

nerve. The vagus nerve (so called because it is

the vagabond nerve that travels throughout the

body, innervating the viscera) is the X-th cranial

nerve. The tonic firing of the vagus nerve slows

down many physiological processes, such as the

heart rate. Research by Porges and his col-

leagues on the PNS has indicated a strong as-

sociation between high vagal tone and good

attentional abilities, and there is speculation that

these processes are related to emotion regula-

tion abilities. Porges (1992) reviewed evidence

that suggests that a child's baseline vagal tone is

related to the child's capacity to react to envi-

ronmental stimuli. There is a substantial body of

literature showing that basal vagal tone is re-

lated to both greater behavioral reactivity and

greater soothability; it is also related to greater

ability to focus attention and greater ability to

self-soothe and explore novel stimuli (DiPietro

& Porges,

1991;

Fox, 1989; Hofheimer & Law-

son, 1988; Huffman, Bryan, Pederson, &

Porges, 1988; Linnemeyer & Porges, 1986; Por-

ter, Porges, & Marshall, 1988; Richards, 1985,

1987;

Stifter & Fox, 1990; Stifter, Fox, &

Porges, 1989).

There is also another dimension of vagal tone

that needs to be considered, namely, the ability

to suppress vagal tone. In general, vagal tone is

suppressed during states that require focused or

sustained attention, mental effort, attention to

relevant information, emotional interaction, and

organized responses to stress. Thus, the child's

ability to perform a transitory suppression of

vagal tone in response to environmental (and

particularly emotional) demands is another in-

dex that needs to be added to the child regula-

tory physiology construct.

2

It relates to the like-

lihood of approach rather than withdrawal;

some infants with a high vagal tone who were

unable to suppress vagal tone in attention-

demanding tasks exhibited other regulatory dis-

orders (e.g., sleep disorders; Huffman, Bryan,

Pederson, & Porges, 1992; Porges, Walter,

Korb,

& Sprague, 1975). Porges, Doussard-

Roosevelt, and Portales (1992) found that

9-month-old infants who had lower baseline

vagal tone and less vagal tone suppression dur-

ing the Bailey examination had the greatest

behavioral problems at 3 years of age, as mea-

sured by the Achenbach and Edelbrock (1986)

Child Behavior Checklist. Measures of infant

1

We did not include the sympathetic portion of the

child's physiology in our modeling. However, we did

find that the child's concentration of adrenaline in the

24-hr urine sample at age 5 correlated (r = 0.39, p <

.001) with the child's illness at age 8.

2

We hypothesize that basal vagal tone is related to

the child's ability to sustain attention, whereas the

ability to suppress vagal tone is related to the child's

ability to shift attention when that is called for.

Porges and Doussard-Roosevelt (in press) pointed

out that one must be cautious about expecting the

suppression of vagal tone to always be the appropri-

ate vagal response to external demands. In the neo-

natal intensive care unit, the appropriate response to

gavage feeding turned out to be increases in vagal

tone,

consistent with the support of digestive pro-

cesses (DiPietro & Porges, 1991). Premature infants

who increased vagal tone during gavage feeding had

significantly shorter hospitalizations.

248

GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

temperament derived from maternal reports

(Bates, 1980) were not related to the 3-year

outcome measures.

3

The Theoretical Challenge in Predicting

Peer Social Competence in Middle

Childhood From Emotion-Coaching

Interactions

A major goal of our research was to predict

peer social relations in middle childhood from

variables descriptive of the family's emotional

life in preschool. It is now well known that the

ability to interact successfully with peers and to

form lasting peer relationships are important

developmental tasks. Children who fail at these

tasks,

especially in the making of friends, are at

risk for a number of later problems (Parker &

Asher, 1987). The peer context presents new

opportunities and formidable challenges to chil-

dren. Interacting with peers provides opportuni-

ties to learn about more egalitarian relation-

ships,

to form friendships with agemates, to

negotiate conflicts, to engage in cooperative and

competitive activities, and to learn appropriate

limits for aggressive impulses. On the other

hand, children are typically less supportive than

caregivers when their peers fail at these tasks. In

our research, we have found that the quality of

the child's peer relationships forms an impor-

tant class of child outcome measures.

We should explain what the theoretical chal-

lenge is in predicting peer social relations across

these two major developmental periods, from

preschool to middle childhood. Major changes

occur in peer relations in middle childhood.

Children become aware of a much wider social

network than the dyad. In preschool, children

are rarely capable of sustaining play with more

than one other child (e.g., see Corsaro, 1979,

1981).

However, in middle childhood, children

become aware of peer norms for social accep-

tance, and teasing and avoiding embarrassment

suddenly emerge (see Gottman & Parker,

1986).

Children become aware of clique struc-

tures and of influence patterns as well as social

acceptance. The correlates of peer acceptance

and rejection change dramatically, particularly

with respect to the expression of emotion. One

of the most interesting changes is that the so-

cially competent response to a number of salient

social situations, such as peer entry and teasing,

is to be a good observer who is somewhat wary,

"cool," and emotionally unflappable (see Gott-

man & Parker, 1986). It is well known that the

worst thing a middle-childhood child can do

when entering a group of

peers

is to start talking

about his or her own feelings as parents and

children do in an emotion-coaching interaction.

Thus,

the basic elements and skills a child

learns through emotion coaching (labeling, ex-

pressing one's feelings, talking about one's

feelings, and drawing attention to one's self)

become liabilities in the peer social world in

middle childhood. Therefore, the basic model

linking emotion coaching in preschool to peer

relations in middle childhood cannot be a sim-

ple isomorphic transfer of social skills model.

Instead, it becomes necessary to identify a

mechanism that makes it possible for the child

to learn something in the preschool period that

underlies the development of appropriate social

skills across this major developmental shift in

what constitutes social competence with peers,

the development in the child of what Salovey &

Mayer (1990) and Goleman (1995) called

"emotional intelligence," a kind of "social

moxie." A number of researchers are addressing

concepts related to this idea of the child's de-

veloping social intelligence, such as the child's

developing ability to cope with stress (Saarni,

1993),

the child's emotional competence (Den-

ham, Renwick, & Hewes, 1994), the child's

developing empathy (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1990;

Eisenberg & Strayer, 1987), the child's devel-

oping social understanding (Denham, Zoller, &

Couchoud, 1994; Dunn & Brown, 1994), the

child's developing social and emotional compe-

tence and regulation as well as the child's de-

veloping theory of social mind (Casey & Fuller,

1994;

Fox, 1994; Harris & Kavanaugh, 1993;

Thompson, 1991), and the child's ability to

recognize emotional expressions (Cassidy,

Parke, & Butkovsky, 1992; Walden, 1988).

3

Time 1 and Time 2 down regulation scales cor-

related

0.41,

p = .003. The Time 1 down regulation

scale was unrelated to awareness and coaching, but it

correlated .31 (p = .020) with derogation, .44 (p =

.004) with Time 2 child negative affect, and 0.59

(p < .001) with Time 2 teacher ratings of negative

peer relations. It was unrelated to scaffolding-

praising parenting, to basal vagal tone, or to suppres-

sion of vagal tone.

META-EMOTION

249

The Theoretical Model: Hypotheses About

Meta-Emotion, Parenting, Regulatory

Physiology, and Child Outcomes

In building our theoretical model, we sought

to explain how meta-emotion philosophy might

be related to a variety of child outcomes. The

theoretical model is depicted in Figure 1. Given

the hypothesized effects of parental meta-

emotion philosophy on parenting skills, we ex-

pected that some effects would occur through

parenting practices. To be specific, we hypoth-

esized that the emotion-coaching meta-emotion

philosophy would be related to scaffolding-

praising and to the inhibition of parental dero-

gation. We also expected meta-emotion philos-

ophy, high scaffolding-praising, and low

derogation to be related to superior emotion

regulation abilities (as indexed by PNS func-

tioning and parental report). We also asked

whether effects between child physiology and

emotion coaching were bidirectional and

whether our effects varied with child tempera-

ment. One concern with these results was

whether parents were coaching their children

differentially as a function of the children's

temperament.

We also proposed that there would be a rela-

tionship between the parents' meta-emotion

coaching philosophy and a variety of child out-

comes. We hypothesized that a parental meta-

emotion coaching philosophy would be related

to the child's developing social competence

with other children. We expected that the

child's peer social competence would hold in

the inhibition of negative affect (Guralnick,

1981),

particularly negativity such as aggres-

sion, whining, oppositional behavior, fighting

requiring parental intervention, sadness, and

anxiety with peers. We also expected that an

emotion-coaching meta-emotion philosophy

would predict the development of superior cog-

nitive skills of the child (through superior vagal

tone and greater ability to focus attention). We

predicted that the relationship between the par-

ents'

meta-emotion philosophy and the child's

achievement at age 8 years would hold over and

above preschool measures of

intelligence.

Thus,

we predicted that two preschool children of

equal intelligence would differ, in part, in their

ultimate achievement in school as a function of

the parents' meta-emotion philosophy. Finally,

we examined the child's physical health as an

outcome variable. Because the vagus innervates

the thymus gland (Bulloch & Moore, 1981;

Bulloch & Pomerantz, 1984; Magni, Bruschi, &

Kasti, 1987; Nance, Hopkins, & Bieger, 1987),

a central part of the immune system that is

involved in the production of T-cells, we also

expected that basal vagal tone would be related

to better child physical health. The path models

also tested direct effects of meta-emotion,

which are theoretically unexplained by the

model.

We recognize that our correlational studies

could not provide us with a causal understand-

ing of the theoretical pathways we proposed.

However, we expected the correlational data to

yield results consistent with or disconfirming

these causal models, thereby suggesting some

directions for future research.

Direct Pathway

Child Outcomes

A

Child Emotion

Regulation Abilities

Figure I. Summary model for how parental meta-emotion might influence child outcomes.

250

GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

Method

An abbreviated set of procedures is presented in

this article in the interests of conserving space. See

Gottman and Katz (1989) and Katz and Gottman

(1993) for more detail.

Participants

Fifty-six normal families were recruited from the

Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, community for this

study; 24 of the families had a male and 32 a female

4-

to 5-year-old child. We used a telephone version of

the Locke-Wallace marital satisfaction scale

(Krokoff,

1984) to ensure that our study included

couples with wide range of marital satisfaction levels.

The mean marital satisfaction score was 111.1 (SD =

29.6).

Three years later, we recontacted 53 of the 56

families (94.6% of the original sample).

Procedure

The procedure involved laboratory sessions and

home interviews for both parents and children. We

used a combination of naturalistic interaction, highly

structured tasks, and semistructured interviews.

Home and laboratory visits consisted of two home

visits-one with the marital couple and one with the

child—and three laboratory visits—one with the cou-

ple only, one with the couple and their 4 to 5-year-old

child, and one with the child alone. Families were

seen at Time 1, when children were 4-5 years old,

and again three years later at Time 2, when children

were on average 8 years old.

Time 1

Assessment

Meta-emotion interview. All parents were sepa-

rately interviewed about their own experience of sad-

ness and anger; their philosophy of emotional expres-

sion and control; and their feelings, attitudes, and

behavior about their children's anger and sadness

(Katz & Gottman, 1986). Their behavior during this

interview was audiotaped. A script for this semistruc-

tured interview is available from John M. Gottman or

Lynn Fainsilber Katz.

Parent- child interaction. The parent- child inter-

action session consisted of a modification of two

procedures used by P. A. Cowan and C. P. Cowan

(1987).

In the first task, parents were asked to obtain

information from their child. The parents were in-

formed that the child had heard a story, and they were

asked to find out what the story was. The story that

the children heard did not follow normal story gram-

mar and was read in a monotone voice; thus, the story

was only mildly interesting for the children and hard

to recall. The second task involved teaching the child

how to play an Atari game that the parents had

learned to play while the child was hearing the story.

The interaction lasted 10 min.

Children's film viewing. During a second visit to

the laboratory, children were shown segments of

emotion-eliciting films. Our main interest was to

obtain indexes of physiological activity during emo-

tional and nonemotional events. Each film clip was

preceded by a neutral story and an emotion induction

film clip of an actress who acted out the emotions of

the protagonist in the upcoming story. The function

of the emotion induction was to direct the child to

identify with the protagonist and experience the spe-

cific emotion in question. Although each film clip

was designed to elicit a specific emotion, the emotion

elicitation was not very successful; instead, we ob-

tained a range of facial expressions of emotion during

in each film. Hence, we refer to the films by their

titles instead of by the emotion they were intended to

induce. The child viewed clips from six films: (a) Fly

fishing; (b) Wizard ofOz (Leroy & Flemming, 1939),

flying monkey scene; (c) Charlotte's Web (Barbara,

Nicolas, & Takamoto, 1973), Charlotte dies; (d)

Meaning of Life (Goldstone & Gilliam, 1983), res-

taurant scene; (e) Wizard of Oz, taking Toto away;

and (f) Daisy (Alcroft & Mitton, 1984).

Child's physiological functioning. We assessed

the following physiological variables from the child

under baseline conditions, during parent-child inter-

action, and during film-viewing:

1.

Cardiac interbeat interval (IBI). This measure

was determined by measuring the time interval be-

tween successive spikes (R-waves) of the electrocar-

diogram (EKG).

2.

Pulse transmission time to the finger (PTT-F).

This was a measure of the elapsed time between the

R-wave of the EKG and the arrival of the pulse wave

at the finger.

3.

Finger pulse amplitude (FPA). This was an

estimate of the relative volume of blood reaching the

finger on each heart beat.

4.

Skin conductance level (SCL). This measure

was sensitive to changes in levels of sweat in the

eccrine sweat glands located in the hand.

5.

General somatic activity (ACT). To measure

somatic activity, the participant's chair was mounted

on a platform that was coupled to a rigid base in such

a way as to allow an imperceptible amount of flexing.

Child intelligence. The Wechsler Preschool

Scales of Intelligence (WPPSI; Wechsler, 1974)

Block Design, Picture Completion, and Information

subscales were administered to each child.

Measure and Coding

Meta-emotion coding system. The audiotapes of

the meta-emotion interview were coded using a spe-

META-EMOTION

251

cific checklist rating system that codes for parents'

awareness of their own anger and sadness, their own

regulation of anger and sadness, and their acceptance

and assistance (coaching) with their child's anger and

sadness (Hooven, 1994). For each dimension, the

coding manual was quite detailed and specific. The

Awareness score was a sum of 12 subscales: experi-

encing the emotion; being able to distinguish the

emotion from others; having various experiences

with the emotion; being descriptive of the experience

of the emotion; being descriptive of the physical

sensations connected with this emotion; being de-

scriptive of the cognitive processes connected with

this emotion; providing a descriptive anecdote;

knowing the causes of the emotion; being aware of

remediation processes; answering questions about the

emotion easily, without hesitation or confusion; talk-

ing at length about this emotion; and showing interest

or excitement about this emotion. Coaching was a

sum of 11 scales: showing respect for the child's

experience of the emotion, talking about the situation

and the emotion when the child is upset, intervening

in situations that give rise to the emotion, comforting

the child, teaching the child rules for appropriate

expression of the emotion, educating the child about

the nature of this emotion, teaching the child strate-

gies to soothe the child's own emotion, being in-

volved in the child's experience of the emotion, feel-

ing confident about how to deal with this emotion,

having given thought and energy to the emotion and

what one wants the child to know about this emotion

(goals), and using strategies that are age and situation

appropriate. Because coders used rating scales, the

appropriate statistics to use for computing interrater

reliability were correlations between independent ob-

servers for each scale, rather than Cohen's kappa,

which is appropriate for categorical data. The range

of interobserver reliabilities for the awareness and

coaching scales was 0.73 to 0.86.

Observational coding of parent-child interaction.

Parenting was coded using the Cowans' Observa-

tional System, the Kahen Engagement Coding Sys-

tem (KECS), and the Kahen Affect Coding Systems

(KACS;

Gottman, in press). The KECS consists of

seven parental engagement codes, including three

positive, three negative, and one neutral code. The

three Kahen positive engagement codes are as fol-

lows:

(a) Engaged, which consisted of parental atten-

tion toward the child; (b) Positive Directiveness, in

which parents issued a directive statement that began

in a positive way (e.g., "move to your right"); and (c)

Responds to Child's Needs, in which parents re-

sponded to a child's question or complaint. The three

negative engagement codes are as follows: (a) Dis-

engaged, in which parents were not attending to the

child; (b) Negative Directiveness, in which parents

issued a directive statement that began in a negative

way (e.g., "Don't move around so much"); and (c)

Intrusiveness, which involved physical interference

with the child's actions (e.g., grabbing the joy stick).

The KACS also consists of seven parental affect

codes.

The three positive affect codes are as follows:

(a) Affection, which consisted of praise and physical

affection; (b) Enthusiasm, which was coded as prais-

ing and excitement at the child's performance; and

(c) Humor, which involved parental laughter or jok-

ing. The three negative affect codes are as follows:

(a) Criticism, which involved direct disparaging

comments or put-downs of the child's behavior or

performance; (b) Anger, in which parents were visi-

bly frustrated by the child's actions or demonstrated

disappointment, annoyance, or irritation toward the

child; (c) Derisive Humor, in which parents used

humor at the child's expense (e.g., through sarcasm

or by making fun of the child).

Parent-child interaction was coded continuously in

real time with coding synchronized to the original

parent-child interaction. The total number of times

each variable occurred in the 10-min parent-child

interaction session was recorded and totals across

time were calculated for each of the 14 parent-child

interaction variables. This index was therefore an

estimate of the frequency of the parenting behavior

within a 10-min period. Independent observers coded

mothers and fathers. Engagement and affect dimen-

sions were also coded by independent observers.

Reliability was calculated across coders using a cor-

relation coefficient. Because total number of seconds

within each parent code was the variable computed

and used in all data analyses, the appropriate reliabil-

ity statistic was a correlation coefficient, rather than

Cohen's kappa or percentage agreement. For the

KECS,

the mean correlation was .96, with a range of

.86 to .99; for the KACS, the mean correlation was

.93,

with a range of .84 to .97. We computed the sum

of derisive humor, intrusiveness, and criticism for

both parents to form our derogation variable. The

Kahen systems were also used to measure the

scaffolding-praising dimension, which consisted of

parental affection, engagement, positive structuring,

responsiveness, and enthusiasm; we computed the

sum of these variables across parents. Although it is

certainly reasonable to expect to find differential

effects of mothers and fathers on children and we

have evidence that maternal and paternal parenting

were uncorrelated (the correlation between mother

and father derogation was .21 and was .12 between

mother and father scaffolding-praising), we summed

across parents* scores for the sake of economy. The

scaffolding-praising dimension differs from Baum-

rind's authoritative parenting in that it includes a

responsive and enthusiastic parenting style; in the

teaching task, this was reflected in parents' (a) effec-

tively structuring and scaffolding the child's learning

and (b) generally waiting until the child did some-

thing right and men praising enthusiastically, rather

252

GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

than waiting until the child made a mistake and then

being critical.

The parents' behavior during the parent-child in-

teraction was also coded using P. A. Cowan and C. P.

Cowan's (1987) coding system. This coding system

codes parents behavior on dimensions of warmth-

coldness, presence or lack of structure and limit set-

ting, whether or not parents back down when their

child is noncompliant, anger and displeasure, unre-

sponsiveness or responsiveness, and whether or not

parents make maturity demands of their child. The

behavior of parents toward each other during their

interactions with their child (their coparenting) was

also coded on dimensions of warmth, cooperation or

competition, anger, disagreement, responsiveness,

pleasure in coparenting, clarity of communication,

and amount of interaction. For the purposes of this

study, only the warmth dimension (parenting and

coparenting) was of interest. For the parenting di-

mension, coders rated the overall degree of warmth

and the highest level of warmth and coldness exhib-

ited by each parent. For the coparenting dimension,

coders rated the overall degree of warmth and the

highest level of warmth and coldness exhibited by the

couple toward each other. Warmth was defined as the

sum of all the warmth variables minus the sum of all

the coldness variables. Interreliability for the warmth

variable was .64.

Child regulatory physiology. An estimate of the

child's baseline vagal tone was taken when the child

was listening to the introduction to an interesting

story taken from an animated cartoon film (clip from

Charlotte's Web), a variable we called basal vagal.

The child's ability to withdraw vagal tone was esti-

mated as a difference between this estimate of basal

vagal tone and the child's vagal tone during an ex-

citing film clip designed to elicit strong emotion (the

scene from The Wizard of Oz when the flying mon-

keys kidnap Dorothy). We expected vagal tone to be

withdrawn and heart rate to increase when the child

was emotionally engaged with the fearful stimuli in

this second film clip. We called this second variable

delta vagal. This second variable indexed the child's

ability to suppress vagal tone when engaging with a

strong emotional stimulus that included an environ-

mental demand for changing attentional focus or reg-

ulating emotion. In this case, the engagement with

the environment involved the demands for an emo-

tional response being elicited by the emotional film

as well as the demands to focus attention on the Atari

videogame the child played immediately after each

film clip. The index of vagal tone was computed as

the amount of variance in the cardiac interbeat inter-

val spectrum that was within the child's respiratory

range using spectral time-series analysis. This index

of vagal tone measures respiratory sinus arrhythmia,

a measure of PNS tonus, which has been found to

index attentional processes and emotion regulation

abilities (Porges, 1984). Mean levels of interbeat

interval at baseline, interbeat interval variability (a

measure of vagal tone; Izard, Porges, Simons, &

Haynes, 1991), reactivity of heart rate variability

from baseline to the mean of the parent-child inter-

action (used as an index of the child's ability to

modulate vagal tone by DiPietro, Porges, & Uhly,

1992),

and mean skin conductance level during base-

line (first visit to the lab) were also computed as

indexes of the amount of the child's chronic physio-

logical arousal and PNS functioning.

Time 2

Assessment

Overview. Time 2 assessment consisted of

teacher ratings of child outcomes and couple's re-

ports of considerations of marital dissolution. Fami-

lies were recontacted 3 years later for follow-up

assessments of child and marital outcomes. Children

were, on average, 8 years old (M = 96.9 months;

range = 82-110 months). Ninety-five percent (53 out

of 56) of the families in the initial sample and 86%

(48 out of 56) of the children's teachers at follow-up

agreed to participate in the Time 2 assessments.

Ratings of children's behavior problems.

Teachers completed the Child Adaptive Behavior

Inventory (CABI; P. A. Cowan & C. P. Cowan,

1990).

We used the CABI as a measure of child

outcomes for two reasons. First, the CABI was de-

veloped on a normal sample and contains subscales

that are less pathological in nature than the Child

Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986).

Second, the CABI also controls for teacher rating

bias by having teachers complete the scale on all

same-sexed children in the classroom and deriving z

scores for the target child. The CABI has good inter-

nal consistency (average alpha =

.81;

range = .66 to

.90) and predictive validity (P. A. Cowan & Cowan,

1990).

The factors and subscales that comprise the

CABI include the following: (a) the Antisocial Fac-

tor, which consists of the Hyperactivity, Antisocial

Behavior, Negative Engagement with Peers, Hostil-

ity, Fairness-Responsibility (keyed negatively),

Calm Response to Challenge (keyed negatively), and

Kindness-Empathy (keyed negatively) subscales;

and (b) the Internalizing Factor, which consists of the

Introversion, Depression, Victim-Rejected, Tension,

and Extroversion (keyed negatively) subscales.

Differential Emotions Scale. We used the Differ-

ential Emotions Scale (Izard, 1982) as a measure of

temperament, given Goldsmith and Campos' (1982)

definition of temperament in terms of affect expres-

sion (for a review and critique, see Bates, 1987). The

Differential Emotions Scale is a 36-item question-

naire that mothers complete with regard to the fre-

quency with which they have observed their children

display specific emotions in the past week. Each item

META-EMOTION

253

is rated on a

5-point

scale ranging from

1

(rarely

or

never)

to 5

(very often).

We

computed

the

total

number of emotions and the total number of positive

and negative emotions for the week.

Teacher ratings

of

peer

aggression.

Teachers

also completed

the

Dodge Peer Aggression Scale

(Dodge, 1986). The Dodge Peer Aggression scale

consists of items that measure the degree

to

which the

child uses overt aggression with peers.

Child academic

achievement.

Children were

in-

dividually administered

the

Peabody Individual

Achievement Test—Revised (PIAT-R) as a measure

of academic achievement (e.g., see Costenbader &

Adams, 1991). They were administered the mathe-

matics, reading recognition, reading comprehension,

and general information tests.

Emotion regulation

questionnaire.

Mothers filled

out

a

newly developed 45-item questionnaire about

the degree

to

which their child requires external

regulation of emotion (Katz & Gottman, 1986). This

questionnaire includes items that reflect instances

when the parent needs to down regulate the child to

reduce

the

child's level

of

activity, inappropriate

behavior, and misconduct. The alpha coefficient for

the scale was .74.

Child physical

health.

Child illness was assessed

by parental report using

a

version of the Rand Cor-

poration Health Insurance Study measures (available

from John M. Gottman or Lynn Fainsilber Katz; see

Gottman

&

Katz, 1989). The following Likert

or

true-false items were summed: "In general, would

you say that this child's health is excellent, good, fair

or poor?," "The child's health

is

excellent," "The

child seems to resist illness very well," "When some-

thing

is

going around this child usually catches it,"

"This child has had a nosebleed in the past 30 days"

(alpha

=

0.82).

Results

We begin

by

discussing

the

selection

and

validity

of

variables used for building the theo-

retical model. The reduced set of variables used

to index meta-emotion philosophy

are pre-

sented, and we address the construct validity of

the derogatory parenting

and

scaffolding-

praising variables by indicating that derogatory

parenting

is not

anger

and

that scaffolding-

praising parenting

is not

warmth.

We

then

present the results

of

our path-analytic model-

ing, looking separately

at

models related to pa-

rental derogation

and to

parental scaffolding-

praising.

We

also test

the

temperament

hypothesis

to see

whether parents select their

parenting style to be consistent with the child's

behavior. Finally,

we

review

the

result that

meta-emotion predicts child academic achieve-

ment

at

Time

2,

even controlling

for

Time

1

child intelligence.

Selection and Validity

of

Key

Theoretical Variables

Reduced Set of Meta-Emotion Variables

In the interest of parsimony, we needed to cut

down the choice

of

variables for the modeling,

and it was thus necessary to limit the number of

meta-emotion variables.

We

started with

12

variables (awareness

of

own emotion, aware-

ness

of

the child's emotion, and coaching,

for

father and mother and

for

sadness and anger).

Two variables from this

set of 12

were con-

structed, one

of

which was the sum

of

parental

awareness of the parents' own emotions and the

sum

of

the parents' awareness

of

the child's

emotions and the other of which was the sum of

the parental coaching

of

the child's emotions.

Table 1 gives

a

summary

of

the correlations of

these

two

summary meta-emotion variables

(i.e.,

awareness and coaching) with the original

12 meta-emotion variables that were obtained.

Therefore,

it

is a presentation of item-total cor-

relations that demonstrate the internal construct

validity

of

the summary codes. These correla-

tions show that the two variables we constructed

are related

to all

the individual awareness and

coaching variables.

Table

1

Correlations

of

the Two Summary Meta-

Emotion Variables With Original 12 Variables

Original meta-

emotion variables

Father sadness

Awareness own

Awareness child

Coaching

Father anger

Awareness own

Awareness child

Coaching

Mother sadness

Awareness own

Awareness child

Coaching

Mother anger

Awareness own

Awareness child

Coaching

*p<.05. **p<.0\

Awareness

.80***

.68***

.26*

.75***

.69***

44***

.56***

.66***

.48***

.57***

.64***

.37**

. ***

p

<

Coaching

.55***

.37**

.63***

.33**

49***

j

4

***

.32**

.63***

.72***

.29*

.36**

.66***

.001.

254 GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

Validity of Child Regulatory Physiology

To examine the validity of the vagal tone

variables, we correlated baseline vagal tone and

suppression of vagal tone with other indexes of

autonomic arousal relating to parasympathetic

activation and general nervous system arousal.

As Table 2 shows, baseline vagal tone and

suppression of vagal tone were related to the

child's mean heart rate during the parent-child

interaction, to the child's lower resting heart rate

during the first visit to the laboratory when it was

a mildly stressful and novel situation, to lower

baseline skin conductance during the second

visit to the laboratory after initial adaptation, to

higher heart rate variability, and to lower heart rate

reactivity in the parent-child interaction.

Validity of Parenting Variables

Derogatory parenting is not anger. In de-

velopmental psychology today, there is a gen-

eral equation of anger and negativity (see Cum-

mings & Davies, 1994), which we consider

unfortunate. When the construct of negative af-

fect is broken into specific negative emotions,

there is evidence that specific negative emotions

serve different functions. In marital interaction,

Table 2

Validity of the Two Child Physiology

Variables Selected for Model Building

Variable

Mean heart rate

during parent-

child

interaction

Mean heart rate

during first

time in the

laboratory

Heart rate

reactivity in

parent-child

interaction

Heart rate

variability

Skin conductance

level after

adaptation to

laboratory

Base vagal

-.26*

-.28*

-.24*

.25*

-.37**

Delta vagal

-.40**

-.33**

-.30*

.39**

-.22

Note. Basal vagal = child's baseline vagal tone;

delta vagal = child's vagal tone when emotionally

engaged.

* p < .05.

**

p < .01.

anger is not predictive of marital dissolution,

whereas contempt is (Gottman, 1993, 1994;

Gottman &

Krokoff,

1989; Gottman & Leven-

son, 1992). Ginott (1965) distinguished anger

versus emotional interactions with the child that

communicated contempt for the child, global

versus specific criticism, and criticism versus

blaming or communications suggesting that the

child was incompetent. He suggested that the

latter communications are harmful to a child,

whereas anger is not and may even be healthy.

To deal with a tendency to overgeneralize and

conclude that anger is harmful for children, we

selected the parental derogation codes from the

Kahen Coding Systems, which were designed to

measure Ginott's cluster of negative parenting;

derogation is not the same as anger parents

express toward children. We tested this

specif-

ically by looking at the relationships between

parental anger and derogation. Parental anger

was uncorrelated with our measure of parental

derogation (for father anger, r = —.11; for

mother anger, r =

—

.06),

uncorrelated with the

meta-emotion codes, and uncorrelated with neg-

ative child outcomes.

Scaffolding-praising is not warmth. It is

important to emphasize that scaffolding-

praising is not merely a dimension of global

positivity, such as is tapped by the Cowan pa-

rental warmth variable. Correlations computed

between the warmth codes from the Cowan

system and the scaffolding-praising code indi-

cated that only maternal warmth was related to

our scaffolding-praising variable (r = .32, p <

.05).

Paternal warmth, maternal and paternal

coldness, and co-warmth all showed no relation

to scaffolding-praising.

Summary of the Seven Dimensions of the

Theoretical Model

Aside from the outcome variables, there are

seven dimensions of the theoretical model. The

two meta-emotion variables were derived from

the meta-emotion coding system used to code

the meta-emotion interview: coaching (a sum of

11 scales) and awareness (a sum of 12 sub-

scales).

The two parenting dimensions were ex-

tracted from the Kahen observational scales,

scaffolding-praising (sum of three scales of the

KECS—engagement, positive directiveness,

and responsiveness to the child's needs—and

two scales of positive affect of the KACS—

META-EMOTION

255

affection-praise and enthusiasm) and deroga-

tion (the intrusiveness code of negative engage-

ment on the KECS and criticism and derisive

humor of the KACS negative affect codes). The

regulatory physiology dimensions were basal

vagal tone (when the child was listening to the

introduction to an interesting story taken from

an animated cartoon film, Charlotte's Web) and

the child's ability to suppress vagal tone, which

was estimated as a difference between this es-

timate of basal vagal tone and the child's vagal

tone during an exciting film clip designed to

elicit strong emotion (the scene from the Wizard

of Oz when the flying monkeys kidnap Dor-

othy).

The emotion regulation dimension was

taken from a questionnaire mothers completed

(when the child was 8 years old) about the

degree to which their child required external

down regulation of emotion.

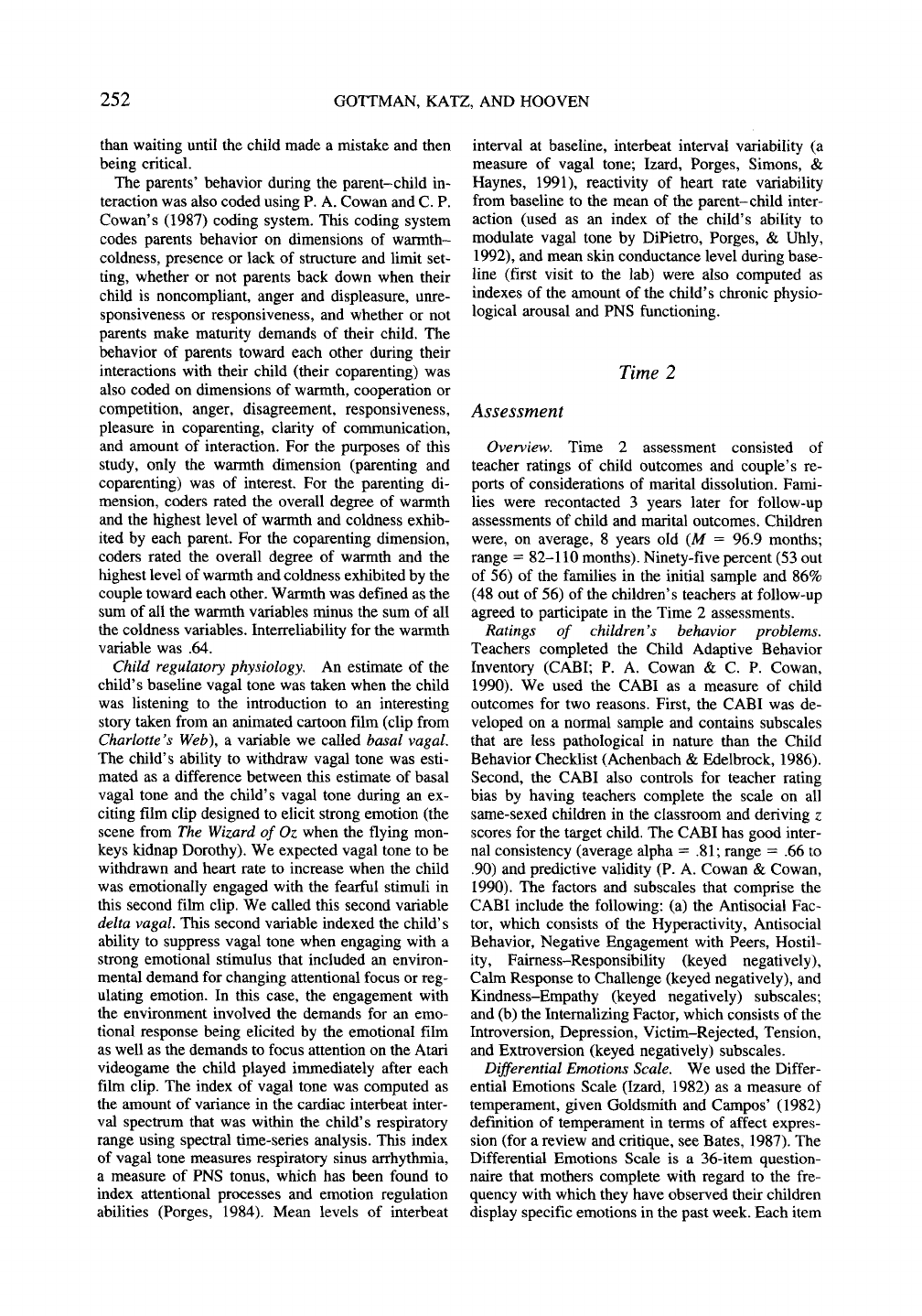

Building the Theoretical Model

The basic template for the theoretical model

is presented in Figure 2. There are eight con-

ceptual pathways consistent with our theoretical

formulation and a direct pathway from meta-

emotion to child outcome. First, we predicted

that there would be statistically significant path

coefficients from the meta-emotion variables to

the parenting variable (Path 1). This was a va-

lidity test to see if the variables derived from

our interview related to actual parenting behav-

ior. Second, we tested the significance of the

paths from meta-emotion and parenting to the

physiological variables (Paths 2 and 3). We

hypothesized that meta-emotion, operating (in

part) through parenting, would significantly af-

fect these physiological variables. That is, we

fundamentally believed that these physiological

variables are not entirely engraved in stone,

even if they are biological; rather, we believed

that these variables are malleable and shaped in

part by parents through their emotional interac-

tions with the child. These conceptual pathways

enable us to assess whether meta-emotion phi-

losophy and parenting in some way are related

to the child's regulatory physiology, or, con-

versely, if the child's regulatory physiology is

related to meta-emotion philosophy or parent-

ing. We also predicted that there would be sta-

tistically significant path coefficients connect-

ing the child physiology variables to the child

outcome variables (Path 4), suggesting that the

child physiology at age 5 years predicts child

outcome at age 8 years (Path 7). We also pre-

dicted the physiological variables would predict

the emotion regulation variable, and that the

regulation and the parenting variables would

relate to child outcome (Paths 5 and 8). We

predicted that parenting would have a direct

effect on child regulation (Path 6). There may

be direct effects between the meta-emotion vari-

ables and the child outcome variables, but, to the

extent that this is true, we have not completely

succeeded in our theory, because we will not have

had a mechanism to explain these effects.

In the interest of data reduction, we created

the following four child outcome variables:

1.

Child achievement was the sum of the

mathematics and reading comprehension

scores.

2.

Child's emotion regulation abilities was

assessed with the Down-Regulation scale of the

Katz-Gottman Emotional Regulation Question-

Delta Vagal

Physiology

Basal Vagal

Child Outcomes

Regulation

Figure 2. Outline of the general expected path structure of the theoretical model.

256 GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

naire, assessed when the children were 8 years

old (called down regulation). Because this is

technically an outcome variable and not a pro-

cess variable (because it was measured when

the children were 8 years old), the emotion

regulation variable appears in every child out-

come model.

3.

Child's peer relations was the sum of three

teacher rating scales: the CABI Negative Peer

scale, the CABI Antisocial Scale, and the

Dodge Peer Aggression scale.

4.

Child illness was our health measure at

age 8.

We built two sets of theoretical models.

Given the hypotheses that meta-emotion philos-

ophy might either be related to the inhibition of

parental derogation or the facilitation of

scaffolding-praising parenting, we constructed

separate models to examine hypotheses related

to derogation and scaffolding-praising. All

modeling computations were performed using

Bentler's (1992) computer program, EQS.

Modeling With Derogatory Parenting

The results of our model building are pre-

sented in Figures 3, 4, and 5. The following are

our goodness-of-fit statistics: for the academic

achievement outcome variable, ^(14, N =

56) = 13.68, p = .474, Bentler-Bonett normed

fit index (BBN) = .981; for the peer relations

outcome variable, ^(13, N = 56) = 17.95,/? =

.159,

BBN = .986; for child illness, ^(12, N =

56) = 13.04, p = .366, BBN = .987. Hence, all

models fit the data. Multiple Rs for the outcome

variables varied: for child academic achieve-

ment, R = 0.41; for negative peer teacher rat-

ings,

R = 0.62; for child physical illness, R =

0.60. The figures present the path coefficients,

with z scores for each coefficient in parentheses.

As can be seen from these figures, the model

building using our theory was generally suc-

cessful. We were able to find linkages for the

major pathways we proposed between meta-

emotion and parenting, between meta-emotion

and the physiological variables, between parent-

ing and the physiological variables for child

peer relations, between physiology and emotion

regulation, between emotion regulation and

child outcome, and between parenting and child

outcome. For child illness, we suggested that

basal vagal tone should relate to less physical

illness, and it turned out that the significant

paths to child illness were parental emotion

coaching and basal vagal tone.

In all models, either awareness or coaching of

the child's emotions was negatively related to

the negative parenting variable, supporting the

hypothesis that awareness or coaching is an

inhibitor of parental derogation of the child. It

was interesting that in all models the child's

ability to suppress vagal tone at age 5 was a

significant predictor of the child's emotion reg-

ulation at age 8. The greater the child's ability

to suppress vagal tone at age 5, the less the

parents had to down regulate the child's nega-

tive affects, inappropriate behavior, and overex-

citement at age 8.

Modeling With Scaffolding-Praising

Parenting

We tested whether the same equations we had

used for negative parenting would fit when the

, Awareness

.73 (6.89)

Figure 3. Path model for child academic achievement with parental derogation. Numbers in

parentheses are z scores.

META-EMOTION 257

(Awareness)

.73 (6.68) ( Derogation

-.47

(-3.72)

.45 (3.65)

-.47

(-3.65)

.48 (4.20)

Child Peer

Relations

A

.31 (2.48)

>( Down Reguate )

v

.61 (5.53)

Figure 4. Path model for child peer relations (teacher ratings) with parental derogation. Numbers

in parentheses are z scores.

parental derogation variable was replaced with the

scaffolding-praising parenting variable. We ex-

pected that some of the path coefficients would

change, but we first tested whether or not a similar

model would fit the data. For the academic

achievement outcome variable, a very similar

model fit the data, ^(14, AT = 56) = 13.12,

p = .517, BBN = .986; for the peer relations

outcome variable, ^(15, N = 56) = 24.14,

p = .063, BBN = .978; for child illness, ^(15,

N = 56) =

18.82,

p = .222, BBN =

.981.

These

results are presented as Figures 6, 7, and 8.

Was scaffolding-praising related to the vari-

ables of the model? For child academic achieve-

ment, the scaffolding-praising variable was sig-

nificantly related to the outcome and to

coaching. For teacher ratings of peer interac-

tion, the scaffolding-praising variable was not

directly related to the outcome, but it was sig-

nificantly related to coaching. For child illness,

the scaffolding-praising variable was unrelated

to the outcome, but it was significantly related

to awareness.

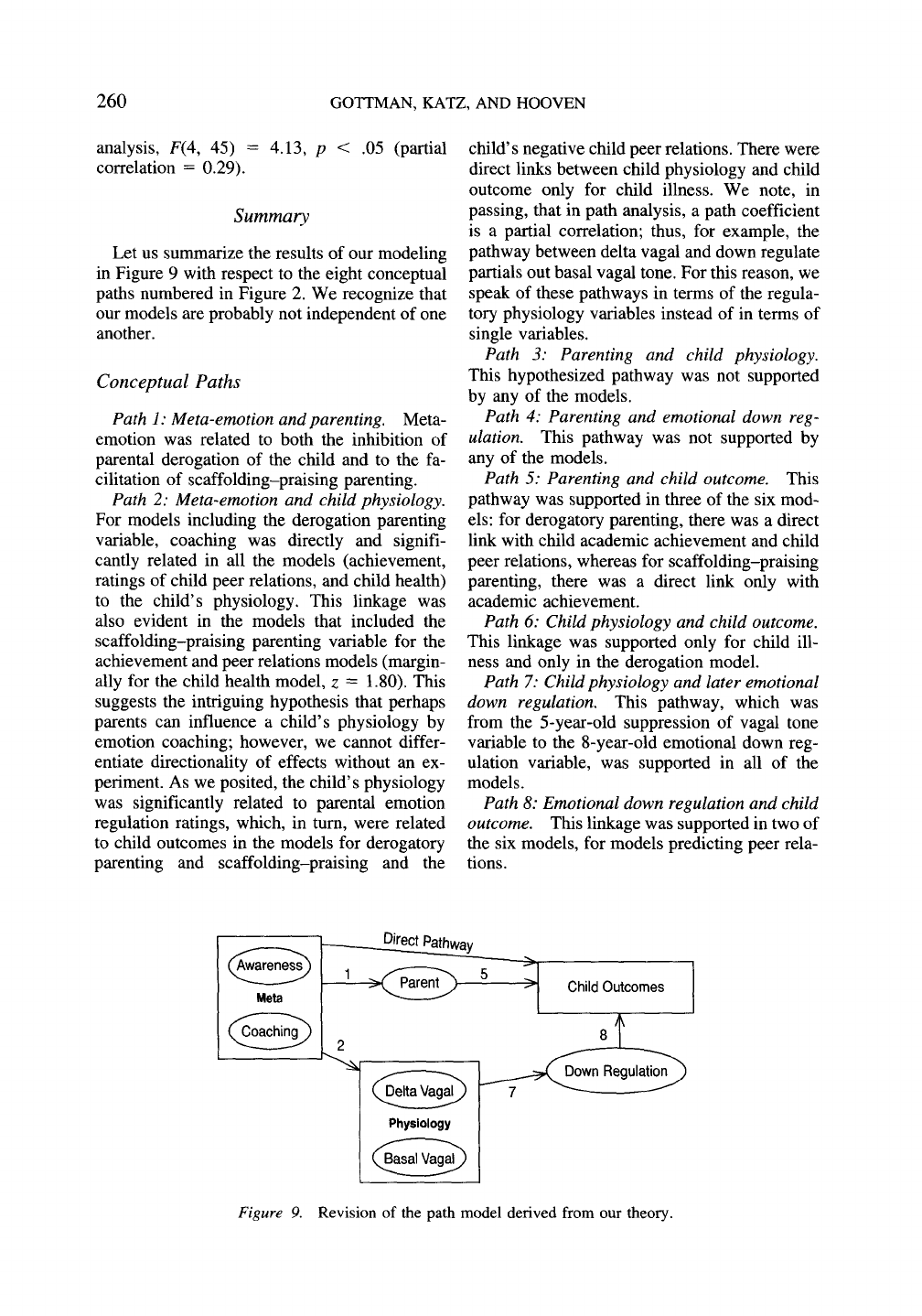

Direction of Effects Between Emotion

Coaching and Child Regulatory

Physiology: Testing the Temperament

Hypothesis

Although our path models present data sup-

porting the notion that emotion coaching can

-.43 (-3.17)

Figure 5. Path model for child illness with parental derogation. Numbers in parentheses are z

scores.

258

GOTTMAN, KATZ, AND HOOVEN

Figure 6. Path model for child academic achievement with positive parenting in the model.

Numbers in parentheses are z scores. SCAF-PR = scaffolding-praising.

affect a child's vagal tone, it is possible that the

direction of effects may be reversed. That is, it

is quite possible that either (a) child physiology

is a part of child temperament, and parents may

select parenting style to be consistent with in-

dividual differences in child behavior or (b)

emotion coaching changes a child's vagal tone.

Perhaps parents are more likely to do emotion

coaching with a child higher in vagal tone, or

perhaps emotion coaching can affect a child's

basal vagal tone. Although we could not answer

causal questions in our path modeling, we did

conduct additional analyses to see if results

either were consistent with or disconfirmed the

temperament hypothesis.

We tested the hypothesis that child vagal tone

might affect emotion coaching by reversing the

arrow between these two variables. The models

fit just as well with the direction of effects

reversed. First, we considered the models with

derogatory parenting. For the child outcome of

negative peer relations,

;^(13,

N = 56) =

19.32,

p = .113, BBN = .985, and the path

coefficient from basal vagal tone to emotion

coaching was .37, z = 3.62. For the child out-

come of child achievement,

)^(14,

N = 56) =

11.28,

p = .664, BBN = .989, and the path

coefficient from basal vagal tone to emotion

coaching was .35, z = 3.74. For the child out-

come of child illness, ^(12, N = 56) = 13.36,

p = .344, BBN = .986, and the path coefficient

from basal vagal tone to emotion coaching was

.33,

z = 3.05. Next, we considered the models

with scaffolding-praising. For the child out-

come of academic achievement, ;^(14, N =

56) = 12.77, p = .545, BBN = .986, and the