Retired Draft

Retired Document

Status Initial Public Draft (IPD)

Series/Number NIST Internal Report (IR) 8389

Title Cybersecurity Considerations for Open Banking Technology and

Emerging Standards

Publication Date January 2022

Additional Information See https://csrc.nist.gov for information on NIST cybersecurity

publications and programs.

Warning Notice

The attached draft document has been RETIRED. NIST has discontinued additional

development of this document, which is provided here in its entirety for historical purposes.

Retired Date May 11, 2023

Original Release Date January 3, 2022

Draft NISTIR 8389 1

2

Cybersecurity Considerations for

3

Open Banking Technology and

4

Emerging Standards

5

6

Jeffrey Voas 7

Phil Laplante 8

Steve Lu 9

Rafail Ostrovsky 10

Mohamad Kassab 11

Nir Kshetri 12

13

14

15

16

This publication is available free of charge from: 17

https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8389-draft 18

19

20

Draft NISTIR 8389 21

22

Cybersecurity Considerations for

23

Open Banking Technology and

24

Emerging Standards

25

26

Jeffrey Voas Rafail Ostrovsky 27

Computer Security Division UCLA 28

Information Technology Laboratory Los Angeles, CA 29

30

Phil Laplante Nir Kshetri 31

Mohamad Kassab University of North Carolina 32

Penn State University at Greensboro 33

State College, PA Greensboro, NC 34

35

Steve Lu 36

Stealth Software 37

Los Angeles, CA 38

39

This publication is available free of charge from: 40

https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8389-draft 41

42

January 2022 43

44

45

46

U.S. Department of Commerce 47

Gina M. Raimondo, Secretary 48

49

National Institute of Standards and Technology 50

James K. Olthoff, Performing the Non-Exclusive Functions and Duties of the Under Secretary of Commerce 51

for Standards and Technology & Director, National Institute of Standards and Technology 52

National Institute of Standards and Technology Interagency or Internal Report 8389 53

45 pages (January 2022) 54

This publication is available free of charge from: 55

https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8389-draft 56

Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an 57

experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or 58

endorsement by NIST, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best 59

available for the purpose. 60

There may be references in this publication to other publications currently under development by NIST in accordance 61

with its assigned statutory responsibilities. The information in this publication, including concepts and methodologies, 62

may be used by federal agencies even before the completion of such companion publications. Thus, until each 63

publication is completed, current requirements, guidelines, and procedures, where they exist, remain operative. For 64

planning and transition purposes, federal agencies may wish to closely follow the development of these new 65

publications by NIST. 66

Organizations are encouraged to review all draft publications during public comment periods and provide feedback to 67

NIST. Many NIST cybersecurity publications, other than the ones noted above, are available at 68

https://csrc.nist.gov/publications. 69

Public comment period: January 3, 2022

- March 3, 2022 70

Submit comments on this publication to: nistir-8389-comm[email protected] 71

National Institute of Standards and Technology 72

Attn: Computer Security Division, Information Technology Laboratory 73

100 Bureau Drive (Mail Stop 8930) Gaithersburg, MD 20899-8930 74

All comments are subject to release under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). 75

76

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

ii

Reports on Computer Systems Technology 77

The Information Technology Laboratory (ITL) at the National Institute of Standards and 78

Technology (NIST) promotes the U.S. economy and public welfare by providing technical 79

leadership for the Nation’s measurement and standards infrastructure. ITL develops tests, test 80

methods, reference data, proof of concept implementations, and technical analyses to advance the 81

development and productive use of information technology. ITL’s responsibilities include the 82

development of management, administrative, technical, and physical standards and guidelines for 83

the cost-effective security and privacy of other than national security-related information in federal 84

information systems. 85

Abstract 86

“Open banking” refers to a new financial ecosystem that is governed by specific security 87

profiles, application interfaces, and guidelines with the objective of improving customer choices 88

and experiences. Open banking ecosystems aim to provide more choices to individuals and small 89

and mid-size businesses concerning the movement of their money, as well as information 90

between financial institutions. Open baking also aims to make it easier for new financial service 91

providers to enter the financial business sector. This report contains a definition and description 92

of open banking, its activities, enablers, and cybersecurity and privacy challenges. Open banking 93

use cases are also presented. 94

Keywords 95

open banking; computer security; privacy; cybersecurity; APIs. 96

97

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

iii

Acknowledgments 98

The authors thank Rick Kuhn, Tom Costello, and Zubin Gautam for their input to this document. 99

100

Audience 101

This publication is accessible for anyone who wishes to understand open banking and the 102

associated cybersecurity and data privacy issues. It is particularly applicable to developers of 103

open banking standards as well as implementers of open banking applications. 104

105

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

iv

Call for Patent Claims 106

This public review includes a call for information on essential patent claims (claims whose use 107

would be required for compliance with the guidance or requirements in this Information 108

Technology Laboratory (ITL) draft publication). Such guidance and/or requirements may be 109

directly stated in this ITL Publication or by reference to another publication. This call also 110

includes disclosure, where known, of the existence of pending U.S. or foreign patent applications 111

relating to this ITL draft publication and of any relevant unexpired U.S. or foreign patents. 112

113

ITL may require from the patent holder, or a party authorized to make assurances on its behalf, 114

in written or electronic form, either: 115

116

a) assurance in the form of a general disclaimer to the effect that such party does not hold 117

and does not currently intend holding any essential patent claim(s); or 118

119

b) assurance that a license to such essential patent claim(s) will be made available to 120

applicants desiring to utilize the license for the purpose of complying with the guidance 121

or requirements in this ITL draft publication either: 122

123

i. under reasonable terms and conditions that are demonstrably free of any unfair 124

discrimination; or 125

ii. without compensation and under reasonable terms and conditions that are 126

demonstrably free of any unfair discrimination. 127

128

Such assurance shall indicate that the patent holder (or third party authorized to make assurances 129

on its behalf) will include in any documents transferring ownership of patents subject to the 130

assurance, provisions sufficient to ensure that the commitments in the assurance are binding on 131

the transferee, and that the transferee will similarly include appropriate provisions in the event of 132

future transfers with the goal of binding each successor-in-interest. 133

134

The assurance shall also indicate that it is intended to be binding on successors-in-interest 135

regardless of whether such provisions are included in the relevant transfer documents. 136

137

Such statements should be addressed to: nistir[email protected] 138

139

140

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

v

Table of Contents 141

1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 142

1.1 Fundamental Banking Functions Provided by Financial Institutions ............... 1 143

1.2 Multiple Financial Institutions .......................................................................... 2 144

1.3 Open Banking Defined .................................................................................... 2 145

2 Use Cases ................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 146

3 Differences from Conventional e-Banking and Peer-To-Peer Financial 147

Platforms ........................................................................................................................ 8 148

4 Survey of Open Banking Approaches Around the World ................................. 10 149

4.1 European Union and United Kingdom ........................................................... 10 150

4.1.1 Development of open-banking standards and API specifications ....... 10 151

4.1.2 From Open Banking to “Open Finance” .............................................. 12 152

4.1.3 The Impact of Privacy and Cybersecurity Considerations .................. 13 153

4.2 Australia ........................................................................................................ 15 154

4.3 India .............................................................................................................. 16 155

4.4 United States ................................................................................................ 18 156

4.5 Other Countries ............................................................................................ 20 157

5 Positive Outcomes and Risks ............................................................................. 23 158

6 Software and Security Practices in Banking-Related Areas ............................ 24 159

7 API Security: Widely Deployed Approaches and Challenges .......................... 25 160

7.1 Intrabank APIs .............................................................................................. 25 161

7.2 Interbank APIs .............................................................................................. 25 162

7.3 API Security .................................................................................................. 26 163

8 Privacy Relations to NIST and Other Standard Frameworks ........................... 27 164

9 Conclusion ................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 165

References ................................................................................................................... 29 166

167

List of Appendices 168

Appendix A— Acronyms ............................................................................................ 36 169

Appendix B— Glossary .............................................................................................. 38 170

171

172

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

1

1 Introduction 173

Open banking (OB) describes a new financial ecosystem that is governed by a set of security 174

profiles, application interfaces, and guidelines for customer experiences and operations. OB 175

ecosystems are intended to provide new choices and more information to consumers, which 176

should allow for easier interaction with and movement of money between financial institutions 177

and any other entity that participates in the financial ecosystem. OB also aims to make it easier 178

for new actors to gain access to the financial sector (e.g., smaller banks and credit unions), has 179

the potential to reduce customers fees on transactions, and is already in use in various countries. 180

1.1 Fundamental Banking Functions Provided by Financial Institutions 181

Financial institutions engage in lending, receiving deposits, and other authorized financial 182

activities. There are nine types of financial institutions [1]: central banks, retail banks, 183

commercial banks, credit unions, savings and loan institutions, investment banks and companies, 184

brokerage firms, insurance companies, and mortgage companies. Central banks (e.g., the U.S. 185

Federal Reserve Bank) only interact directly with other financial institutions. The rest of these 186

financial institutions interact with individuals, companies, and each other in different ways. For 187

example, banks may act as financial intermediaries by accepting customer deposits or by 188

borrowing in the money markets. Banks then use those deposits and borrowed funds to make 189

loans or to purchase securities. Banking entities also make loans to businesses, individuals, 190

governments, and other entities. This document uses the term “banking entity” to refer to any 191

financial institution that conducts business with individuals, such as a retail bank, credit union, or 192

mortgage company. Figure 1 illustrates some monetary flows between banking entities, their 193

customers, and other entities in the financial system. 194

195

Figure 1 - Some typical interactions between banking entities, their customers, and other entities [2] 196

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

2

banks include individuals, merchants, service providers, governments, utilities, non-profit 199

organizations, other banking entities, and others (e.g., consumers, investors, and businesses). 200

Financial sector institutions also serve as financial intermediaries by facilitating payments to and 201

from their customers to the businesses and other entities with which they interact via check 202

payments and debit and credit transfers. Some banking entities provide other services to their 203

customers, such financial planning and notary services. 204

1.2 Multiple Financial Institutions 205

A customer can interact with more than one financial institution. For example, a person may use 206

a local bank for everyday transactions, a credit union to hold the home mortgage, a car financing 207

firm to finance a car, and one or more other banks for credit cards. However, moving funds 208

between these financial institutions is not always easy or transparent. For example, making a 209

payment to an auto loan through a credit transfer from the local bank requires several customer 210

actions, and making a mortgage payment from an advance on a credit card requires certain 211

authorizations. 212

Customers may be forced to accept most (or all) of a package of services offered by a financial 213

institution. Customers usually cannot “mix and match” services offered by different banking 214

entities easily. For example, it would be unusual to have a checking account with one bank, a 215

money market account with another, a savings account with another, and debit card with yet 216

another bank. Moving funds between these different accounts would likely require several steps 217

and authorizations, including fees. 218

1.3 Open Banking Defined 219

Open banking describes a new kind of financial ecosystem that gives third-party financial service 220

providers open access to consumer banking, transactions, and other financial data from banks 221

and non-bank financial institutions through the use of application programming interfaces 222

(APIs). It is governed by a set of security profiles, application interfaces, and guidelines for 223

customer experiences and operations. Ecosystem-enabled banking means that there are not 224

predefined direct relationships or “supply chains” of financial products and services. Rather, the 225

flow of debits and credits between these products and services are executed at the discretion of 226

the customer (see Figure 2). 227

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

3

228

The term “open banking” can be used as a noun that defines any conforming financial ecosystem 230

(e.g., “the XYZ bank conducts open banking”). “Open banking” can also be used as an adjective 231

(e.g., “open banking guidelines” or “open banking API”). OB can be thought of as “finance as a 232

service” (FaaS), a form of software as a service (SaaS). In Figure 2, the open banking cloud is a 233

collection of banking entities that are configured as a cloud and deliver micro and macro 234

financial services via SaaS using conforming APIs. Financial microservices include deposits, 235

withdrawals, payments, debits, credits, and more; macro services include loan origination and 236

payoff, mortgage origination, and the like. Within the open banking cloud in Figure 2, there are 237

clouds that represent one or more financial institutions that participate in the OB ecosystem (see 238

Figure 3). 239

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

4

240

OB is consistent with the goal of moving towards a “cashless economy” by using digital 242

payments. However, it requires banks to remove proprietary barriers and share information with 243

third parties. This opening and sharing of data forces banking entities to make proprietary data 244

available to any entity with the owner’s permission to access it. 245

In OB, banking entities interact with each other via APIs at the customer’s direction and can 246

offer better services on an a la carte basis. With a larger available set of services, customers can 247

personalize their finances with more suitable, balanced, and cost-effective products. For 248

example, a customer could choose one banking entity’s savings account service, another banking 249

entity’s checking account service, another’s credit card, another’s auto loan, and another’s 250

mortgage product, and funds could be moved seamlessly through all of these services. 251

Dashboard tools could help customers perform various transactions, aggregate information for 252

analysis and optimization, set activity alarms, and so on. 253

Aggregated accounts enable new insights and enhanced speed, convenience, and simplicity of 254

transactions. Aggregated accounts could belong to the balance sheets that clients select, or each 255

bank might only count its own accounts on its balance sheet. OB also makes it easier for smaller 256

financial product vendors to enter into the financial services industry. 257

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

5

2 Use Cases 258

Section 2 provides use cases to illustrate expected open banking experiences [3]. 259

Use Case 1, Recurring Payments: Members of a household juggle multiple recurring payments 260

for their mortgage, four credit cards, car insurance (insurance agency X), home insurance 261

(insurance agency Y), life insurance (insurance agency Z), healthcare (exchange Q), property 262

and income taxes, utilities, and much more. The household income (from three sources) appears 263

as direct deposits into two banks. One member of the household is responsible for managing the 264

finances. This member is finding it difficult to keep track of all of the sources of funds and has 265

occasionally incurred costly penalties for missed and late payments and overdrafts. OB would 266

allow the sources of income from different sources and all of the recurring expenses to be 267

displayed on one or more dashboards that provide statuses, alerts for payment, and seamless 268

access to funds from any source, including consolidated account overdraft protection. 269

Aggregating this information also allows for the optimization of payment scheduling (to reduce 270

interest charges) and the movement of money between revenue-generating accounts. Artificial 271

intelligence can provide additional insights to optimize cashflow, minimize lateness, and lead to 272

a higher credit rating for members of the household. 273

Use Case 2, Multiple Accounts: An individual has checking accounts at two different banks and 274

a credit card financed through a third bank. The individual wishes to make large purchases that 275

exceed the funds in any checking account or credit card limit. However, the OB allows the 276

individual to seamlessly combine these sources into an available balance that is sufficient to 277

make a large purchase, as well as covering shortfalls on any account as needed via direct 278

transfers between accounts. Once the consumer makes a purchase, the checking accounts and 279

credit card are debited accordingly. 280

Use Case 3, Linking Payments: A certain large banking entity no longer offers personal lines of 281

credit but supports OB. An individual customer wishes to continue everyday business with the 282

large bank but obtains a personal line of credit through a different banking entity that supports 283

OB. Through OB, more seamless payment of bills from a day-to-day operational perspective is 284

possible. For example, direct credit transfer can be used to pay the principal and interest on the 285

line, link to the savings and checking accounts for overdraft protection on the line of credit, and 286

transfer between accounts. These OB experiences all occur as if all accounts were held by one 287

large bank. 288

Use Case 4, Auto Purchase: An individual wishes to purchase a new car from a dealer. The 289

individual selects the particular model and options and negotiates with the dealer on the purchase 290

price. Using OB, the auto dealer conducts a rapid credit check on the buyer, sends financial 291

information to various loan agencies, and receives multiple loan offers and terms from various 292

finance sources. The buyer selects the preferred loan, and the purchase down payment is directly 293

paid to the dealer from a selected banking entity serving the customer. The payment plan is set 294

up with a loan agency, and overdraft protection is set up by linking regular load payment sources 295

(e.g., checking account) to other secondary financial sources (e.g., savings, investment accounts). 296

The complete set of financial transactions takes only a few minutes. 297

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

6

Use Case 5, Small Business Loan Origination: A small and medium enterprise (SME) owner 298

wishes to obtain a loan to purchase new equipment for their expanding business. The owner has 299

been unable to get a loan from traditional banks, including their regular bank. Part of the 300

difficulty in obtaining the loan has been the effort required to collect all of the financial 301

information needed for the loan application while simultaneously trying to run the business. 302

Using an OB application, however, the business owner can more easily gather the information 303

needed for the loan applications, shop more loan sources, and select from several options in 304

order to get the most favorable loan terms. 305

Use Case 6, New Banking Entities: Consider the collection of SME and large banking entities 306

participating in the activities of Use Cases 1-5. Many of these entities would not be able to 307

connect with nor have the opportunity to offer products and conduct business with the customers 308

in these Use Cases without the OB ecosystem. 309

Use Case 7, Wealth Management: Digital wealth management platforms are on the rise and 310

can benefit from the OB system to gain a clearer context of a client before recommending an 311

appropriate investment based on the client’s payment ability and risk tolerance. Companies that 312

can implement this use case in the U.K. include Plum (https://withplum.com/), Chip 313

(https://getchip.uk/), and Lenlord (https://www.lendlord.io/). 314

Use Case 8, Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL): A small retailer wants to implement a BNPL 315

campaign that allows users to receive their purchased items before payments are finished. A 316

typical step in traditional BNPL programs is determining a customer’s credit risk before 317

extending credit. This step is usually outsourced by small retailers. Using an OB framework, a 318

specialized company can smooth the interaction between retailer and customer and reduce the 319

burden on the retailer. OB-developed applications can aggregate more information about the 320

customer’s spending habits and use proprietary algorithms to help make a better-informed 321

decision about the creditworthiness of a user. Companies that can implement this use case 322

include Zilch (https://www.payzilch.com), Klarna (https://www.klarna.com), and Afterpay 323

(https://www.afterpay.com/en-US). 324

Use Case 9, Improving Employee Experience: A company wants to offer its employees 325

discount packages at retailers in their community. Typically, such a program would require proof 326

of employment to qualify for a discount, at which time an adjustment to the retailer’s point-of-327

sale system needs to be made. OB can streamline this process by connecting the employee’s 328

existing credit or debit card to their discount profile and unlocking eligible deals in their 329

community. Moreover, AI capabilities can further augment the OB-developed system. By 330

analyzing the employee’s banking transactional data, the discounts can be targeted to the 331

interests of each employee instead of a blanket discount voucher. Because there is no need to 332

modify the vendor’s system, it is also easier for a small retailer to participate in an employee 333

discount program. Companies that can implement this use case include Perkbox 334

(https://www.perkbox.com/uk). 335

Use Case 10, Debt Collection: A customer is behind on certain loan payments. Using open 336

banking, a debt collector can look into the accounts of the person and try to generate a payment 337

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

7

plan that the debtor can meet to pay off the remaining amount. Companies that can implement 338

this use case include Experian (https://www.experian.com/) and Flexys (http://flexys.com/). 339

Use Case 11, Carbon Tracking: An individual is interested in learning about the impact that 340

their spending has on the environment. An OB system connected to a carbon-tracking platform 341

can provide the user with carbon footprint insights based on their banking transactions, allowing 342

them to become more conscious about their environmental impact. The system can also offer 343

recommendations to engage in changing spending behaviors in a win-win ecosystem. Companies 344

that can implement this use case include Enfuce (https://enfuce.com/) and equensWorldline 345

(https://equensworldline.com). 346

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

8

3 Differences from Conventional e-Banking and Peer-To-Peer Financial 347

Platforms 348

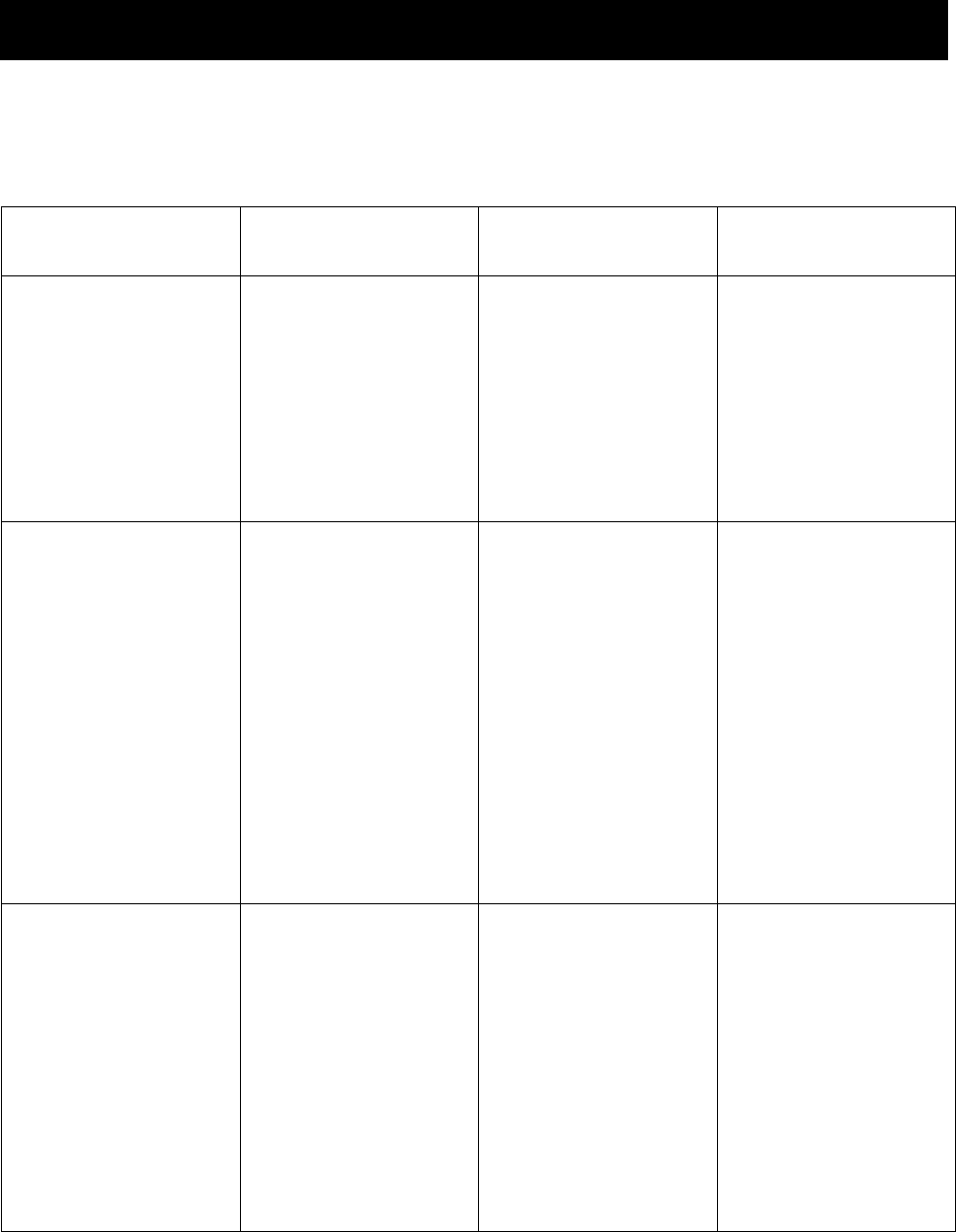

Key differences between open banking and conventional e-banking and peer-to-peer (P2P)

349

financial platforms are pre

sented in Table 1. 350

Table 1 - Comparing OB, conventional e-banking, and P2P financial platforms [2] 351

Open Banking

Conventional e-

Banking

P2P Financial

Platforms

Privacy and security

aspects

Privacy and security

issues are of concern

among large

proportions of lenders

and consumers [4].

Many are

implementing strong

security and privacy

measures, including

biometric login

options involving

fingerprint, voiceprint,

and facial recognition

[8].

Cybercriminals have

been reported to use

compromised

identities from

massive data breaches

to get loans [10].

Adoption and use

Only a few

jurisdictions have

developed OB

regulations, and the

current regulatory

environment has been

a concern in most

economies [4].

In addition to well-

established e-banking

services offered by

existing banks, some

economies such as

Hong Kong SAR,

South Korea,

Malaysia, Singapore,

Taiwan, and the

Philippines have

issued bespoke digital

banking licenses to

operate online-only

banks [5].

The regulatory

environment is

complex and varies

significantly across

countries.

Potential effects on

mainstream banking

systems

There is the

opportunity to work

with FinTechs to

launch innovative

products and adopt

ways to enhance

customer experience

and loyalty. With

streamlined processes

and new products,

new customers can be

gained, and existing

There are lower

overhead costs than

brick-and-mortar

operations.

P2P loans typically

offer investors a

higher rate of return

(albeit riskier)

compared to bank

deposits. Such a

competition forces

banks to fund their

activities using more

costly non-deposit

funding sources [6].

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

9

Open Banking

Conventional e-

Banking

P2P Financial

Platforms

customers can be

retained. However,

banks may lose some

income from fees.

Potential benefits to

consumers

There is access to

additional products

that customers’

current banks cannot

offer, as well as

diversified access to

products [7].

E-banking offers

convenience (e.g.,

24/7 account access)

and control over

finances with the

ability to self-serve

[8].

High-risk borrowers

not served by

traditional banks

could get access to

loans. Consumers,

however, often pay

higher interest rates

than for loans from

the traditional banking

sector [9] or private

lenders.

Ordinary electronic banking (e-banking) is already well-established. None of the micro or macro 352

services provided by banks require a physical structure or proximity, and all can be conducted 353

online. Many banking entities serve their customers entirely through online services without the 354

need for physical branch offices. These e-banks provide capabilities for electronic deposits, the 355

withdrawal of funds, remote scanning of physical checks for deposit, electronic transfers, auto 356

deposits, auto debits, account analysis, transaction alerts, reminders, and more. Many 357

conventional banks also offer an electronic interface and other third-party e-banking solutions 358

that provide a “wrapper façade” for a mobile banking layer between the user and their bank. 359

However, these e-banking activities all occur within the closed system of banking entities 360

subscribed to by a customer and are predefined and not transparent. Further, proprietary 361

information kept by each banking entity curtails the optimization and customization of services 362

and the consolidation of information. 363

P2P financial platforms (e.g., Venmo, PayPal, Google Pay) offer digital wallets with money held 364

by the platform host and allow for transfer to and from linked debit cards, credit cards, or bank 365

accounts depending on the service. Yet beyond the electronic wallet feature, P2P financial 366

platforms offer few of the other services offered by traditional banks and, therefore, fall far short 367

of the capabilities of OB. Thus, e-banking services and P2P financial networks can benefit by 368

entering the OB ecosystem. 369

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

10

4 Survey of Open Banking Standards and Approaches Around the World 370

National approaches to open banking across the globe are frequently characterized broadly as 371

either regulatory or market-driven [11][12]. However, the adoption of open banking in many 372

countries might better be characterized as a hybrid approach with legal and regulatory mandates 373

driving certain aspects of open banking and market forces driving others. This section gives a 374

high-level survey of some national and regional approaches to open banking with a particular 375

focus on the role that privacy and cybersecurity considerations have played in the development 376

and implementation of these approaches. 377

4.1 European Union and United Kingdom 378

The E.U. and the U.K. have taken closely related and solidly regulatory approaches to open 379

banking, resulting in their reputations as open banking’s primary pioneers [11][13][14]. The 380

regulatory origins of open banking in the E.U. and the U.K. can be traced to the EU's Revised 381

Payment Services Directive (PSD2), which was adopted by the European Parliament, passed by 382

the Council of the European Union in 2015, and came into force under EU-member national laws 383

and regulations in early 2018 [15]. 384

With the goal of promoting competition and innovation in the payments market, PSD2 requires 385

Account Servicing Payment Service Providers (ASPSPs) – essentially, banks and other financial 386

institutions (FIs) at which customers hold payment accounts – to open their payment services to 387

regulated third-party payment service providers (TPPs) with customers’ consent. These TPPs, 388

which include FinTechs and other new players in the payments market that could also be FIs 389

themselves, include payment initiation service providers (PISPs) and account information service 390

providers (AISPs). PISPs provide services to initiate payments at the request of a customer using 391

the customer’s payment account held at an FI, whereas AISPs offer online services that provide 392

consolidated information on a customer’s payment accounts held at one or more FIs [15] (Article 393

4(15)–(19)). 394

More precisely, Articles 66 and 67 of PSD2 require E.U. Member States to establish and 395

maintain the rights of customers to make use of services from PISPs and AISPs, respectively, 396

and require FIs to enable those TPP services through the use of secure communications. In short, 397

PSD2 made participation in open banking compulsory for FIs in the EU, which included the U.K. 398

during the pre-Brexit time period of PSD2’s enactment and coming into force, at least with 399

respect to regulated TPPs. The U.K.’s implementation of PSD2 as the Payment Services 400

Regulations 2017 (PSRs 2017) remains in effect, although certain post-Brexit amendments to the 401

regulations are expected [16][17]. 402

4.1.1 Development of Open Banking Standards and API Specifications 403

The U.K. has seen a somewhat more rapid implementation of OB APIs than the EU. In 2017, 404

based on an investigation report published in August 2016, the U.K. Competition and Markets 405

Authority (CMA) ordered the nine largest U.K. banks at the time – HSBC, Barclays, Santander, 406

Bank of Ireland, RBS, Allied Irish Bank, Danske Bank, Nationwide, and Lloyds, collectively 407

known as the “CMA9” – to implement common open banking standards that would allow 408

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

11

customers to share their banking data with licensed TPPs through the use of standardized APIs 409

[18]. Perhaps the most notable distinguishing feature of this order is that it created a regulatorily 410

mandated set of open banking standards, including API and security-profile specifications. 411

Specifically, the CMA order directed the CMA9 to establish the Open Banking Implementation 412

Entity (OBIE, also known under the trading name Open Banking Limited) – a private, non-profit 413

entity with a steering group comprising representatives of the CMA9 banks, FinTechs, payment 414

service providers, challenger banks, consumers, small businesses, other stakeholders, and 415

observers from U.K. government regulators [19]. The OBIE was tasked with agreeing upon, 416

implementing, and maintaining freely available, open, read-only, and read/write data access 417

standards, which were to include an open API standard, data format standards, security 418

standards, governance arrangements, and customer redress mechanisms for the read/write 419

standard [18]. 420

The resulting Open Banking Standard was launched in January 2018, and the expanded Version 421

3 was published in September 2018. Designed as a “PSD2-compliant solution ([20]),” Version 3 422

of the U.K. Open Banking Standard includes four core components: (1) API specifications 423

(including read/write API specifications, open data API specification, open banking directory 424

specifications, dynamic client registration specifications, and management information (MI) 425

reporting specifications), (2) security profiles based on the Open ID Foundation’s Financial-426

grade API (FAPI) and Client Initiated Backchannel Authentication (CIBA) profiles, (3) customer 427

experience guidelines, and (4) operational guidelines to support ASPSPs in requesting an 428

exemption from PSD2 requirements to provide a so-called “contingency mechanism” in addition 429

to Open Banking Standard-compliant APIs, as discussed further below. Although the CMA 430

mandate requires only the CMA9 banks to comply with the Open Banking Standard, it has likely 431

resulted in a U.K. open banking environment harmonized around clear, regulation-driven 432

specifications. Indeed, the OBIE’s monthly highlights report 91 regulated ASPSPs (presumably 433

including the CMA9) and 234 regulated TPPs, with 114 regulated entities that “have at least one 434

proposition live with customers” in the U.K. open banking ecosystem [21]. 435

In contrast to the U.K.’s approach of establishing and developing concrete open banking 436

standards through regulatory mandate, the E.U. has essentially left the task of standardization to 437

the market [13][14]. Although PSD2 establishes a legal and regulatory framework requiring FIs 438

and other ASPSPs to establish interoperable communications with registered TPPs, it does not 439

provide for technical open-banking API specifications akin to the U.K.’s Open Banking 440

Standard. Article 98 of PSD2 (“Regulatory technical standards on authentication and 441

communication”) directed the European Banking Authority (EBA) to draft regulatory technical 442

standards (RTS) specifying, in part, “the requirements for common and secure open standards of 443

communication for the purpose of identification, authentication, notification, and information, as 444

well as for the implementation of security measures” between ASPSPs, TPPs, payers, and 445

payees. However, the resulting final draft RTS describes requirements for such “common and 446

secure communication” at a high level and does not mention, mandate, or provide technical 447

specifications for APIs as a prescribed or suggested communication interface. The EBA’s 448

feedback on responses from public consultation accompanying the final draft RTS note that 449

“[t]he RTS do not mandate APIs although the EBA appreciates that the industry may agree that 450

they are suitable” [22]. 451

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

12

Industry consensus in the E.U. appears to have settled broadly on the use of open-banking APIs 452

[23] despite the silence of PSD2 and the accompanying RTS on APIs. However, the lack of 453

regulatory clarity and specific mandated technical standards has arguably impeded the 454

development of detailed API specifications and harmonization around such specifications across 455

the EU. Some of the more notable E.U. open banking API standards include the Berlin Group’s 456

NextGenPSD2 standard, STET’s PSD2 API, Swiss Corporate API, and PolishAPI [24]. 457

Although approximately 78 % of E.U. banks relied on the NextGenPSD2 standard as early as 458

late 2018, the EU’s environment has still been comparatively more fragmented than that of the 459

U.K. in the early years of open banking [25][26][24]. Nonetheless, the regulatory foundation 460

provided by PSD2 has resulted in the EU’s standing as a pioneer and ongoing leader in open 461

banking. MasterCard’s Open Banking Readiness Index 2021 has recently ranked Sweden, 462

Denmark, and Norway ahead of the U.K. for open banking readiness (owing primarily to those 463

countries’ established schemes for digital ID authentication and know-your-customer (KYC) 464

services) [24][13]. Moreover, the Euro Retail Payments Board (ERPB) working group is set to 465

begin work on a SEPA (single euro payments area) API Access Scheme to further the integration 466

of the European open banking market and address business requirements, governance 467

arrangements, and a standardized API interface [23]. 468

4.1.2 From Open Banking to “Open Finance” 469

PSD2 currently provides a legal framework that regulates only the sharing of payment data by 470

ASPSPs with TPPs. For example, the sharing of data related to loans, mortgages, investments, or 471

insurance is not within the purview of the PSD2 regulations. Although the U.K. Open Banking 472

Standard provides a regulated data-sharing framework somewhat broader than that of PSD2 – in 473

particular by establishing procedures to allow data access to a broader range of trusted third-474

party entities than the licensed payment service providers covered by PSD2 – the regulatory 475

framework for open banking across the European Economic Area and the U.K. remains largely 476

focused on payment services. As open banking has become established in Europe, there has been 477

a push toward a broader conception of “open finance,” which would create a similar framework 478

for the sharing of financial data beyond payment account data. 479

With the CMA order’s implementation phase set to conclude in 2021, the banking and financial 480

services trade association, U.K. Finance, has proposed that the OBIE be transitioned to a new 481

industry-run services company, noting that this future entity should work to extend open banking 482

into open finance given that “[c]ustomers do not see the relevance of the PSD2 boundary 483

[between payment and other financial services] to their financial lives” [27][28]. Similarly, the 484

U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) – a financial regulatory body independent of the U.K. 485

government – has recently published feedback to its 2019 Call for Input on open finance, noting 486

a “degree of consensus” among responding stakeholders that, similar to open banking, a broader 487

open finance ecosystem would require basic elements such as a legislative and regulatory 488

framework, common standards, and an implementation entity [29]. Calls for a transition to open 489

finance have also occurred in the E.U. For example, in October 2020, the Berlin Group 490

announced that it would begin work on an “openFinance API Framework” [30]. 491

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

13

4.1.3 The Impact of Privacy and Cybersecurity Considerations 492

Although the E.U.’s introduction of PSD2 and the CMA’s open banking efforts in the U.K. were 493

initially motivated by a desire to increase competition and innovation in the banking and 494

payment sectors, the E.U. and U.K. frameworks have expanded their focus to considerations of 495

customer experience, customer data rights and control, privacy, and security. A 2018 survey by 496

PricewaterhouseCoopers found that “the risks of data management, fraud[,] and loss of privacy” 497

were major payment customer concerns, with 48 % of retail customers and 54 % of SMBs 498

surveyed expressing such concerns with respect to data sharing in open banking [14]. 499

As one aspect of addressing payment security, PSD2 and its accompanying RTS require payment 500

service providers to apply “strong customer authentication” (SCA) – essentially amounting to 501

multi-factor authentication – in scenarios where a payer “accesses its payment account online,” 502

“initiates an electronic payment transaction,” or “carries out any action through a remote channel 503

which may imply a risk of payment fraud or other abuses” [15] (Article 97(1)). The 3D Secure 504

2.0 (3DS2) protocol has emerged as the primary method for authenticating payments in 505

compliance with PSD’s SCA requirements for card-not-present transactions, though unified 506

adoption of the protocol and national enforcement of the SCA requirement have experienced 507

delays relative to the initial implementation timeline [31]. Additionally, payments consultancy 508

CMSPI reported testing in September 2020 showing that 35 % of 3DS2 transactions were 509

declined, abandoned due to customer frustration, or failed due to technical errors. At the time, 510

CMSPI estimated that such transaction failures, if not reduced, could result in losses to European 511

merchants exceeding €100 billion based on 2019 sales volumes [32]. 512

Much of the technological discussion of privacy and security in OB – not only with respect to the 513

E.U. and U.K. ecosystems but globally – has focused on the superior security of open APIs 514

relative to the practice of screen scraping, in which customers provide their payment-account 515

access credentials (such as username and password) directly to third-party providers who use 516

those credentials to access and gather customers’ data from an FI (or other ASPSP). Screen 517

scraping raises security and privacy concerns for both customers – not least because the practice 518

frequently grants a third-party access to considerably more of a customer’s data than is needed 519

for the particular service that the customer is requesting – and FIs, who can face in the event of 520

data breaches or data misuse resulting from third-party screen scraping, even where scraping is 521

applied without the FI’s knowledge [11][14]. 522

Notably, the RTS on Strong Customer Authentication and Common Secure Communication 523

under PSD2 limits but does not impose an outright ban on screen scraping by TPPs. Although 524

the RTS does effectively prohibit screen scraping as it was most frequently practiced prior to 525

PSD2, some form of permissible screen scraping survives in the form of contingency 526

mechanisms (alluded to in the description of the U.K. Open Banking Standard), also referred to 527

as “fallback mechanisms.” Specifically, as a compromise between the security risks of screen 528

scraping and the potential competitive disadvantage to TPPs if an ASPSP’s “dedicated interface” 529

(i.e., API) fails or is unavailable, Article 33 of the RTS requires ASPSPs to grant TPPs access to 530

their usual customer-facing authentication and communications interfaces as part of a 531

contingency mechanism in the event of such failure or unavailability, essentially allowing TPPs 532

to practice screen scraping as a contingency mechanism. However, the RTS requires TPPs 533

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

14

utilizing such contingency measures to identify themselves to the relevant ASPSP prior to 534

scraping, which theoretically mitigates some of the security risk for the ASPSP [33]. Moreover, 535

the PSD2 RTS provides conditions under which an ASPSP could qualify for an exemption from 536

the requirement to provide a fallback mechanism (see previous discussion of the U.K. Open 537

Banking Standard) [34][35][36]. 538

Even assuming the use of PSD2-compliant open APIs, significant privacy and cybersecurity 539

concerns and attendant liability concerns necessarily remain in an open banking ecosystem 540

premised on the sharing of individual consumers’ data. In this direction, the E.U.’s General Data 541

Protection Regulation (GDPR) ([37]) plays a crucial role alongside and beyond PSD2 in the legal 542

and regulatory framework of the European open banking ecosystem

1

. 543

GDPR Article 25, “Data protection by design and by default,” and Article 32, “Security of 544

processing,” are of particular interest with respect to the technological aspects of privacy 545

considerations for open banking. Article 25 may be viewed as creating a legal mandate for “data 546

controllers” (i.e., entities that determine the purpose and means of processing individuals’ 547

personal data) to adopt both technical and organizational measures that implement the principles 548

of “privacy by design” [39]. In the context of the PSD2 open banking framework, GDPR “data 549

controllers” include both ASPSPs (such as FIs) and TPPs. In addition to imposing privacy by 550

design, Article 25 requires organizations to only process personal data that are necessary for the 551

specific purpose to be accomplished by the processing. This requirement makes explicit the 552

application of GDPR’s “data minimization” and “purpose limitation” principles to limiting the 553

storage of customers’ data by ASPSPs and TPPs (as well as data controllers more generally) 554

[39]. Article 32 also requires organizations to implement technical and organizational measures 555

“to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk” presented by data processing, in particular 556

from destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorized access, or disclosure of personal data that are 557

transmitted, stored, or otherwise processed [37] (Article 32). 558

Notably, both Article 25 and Article 32 require organizations to “tak[e] into account the state of 559

the art” in determining appropriate technical and organizational measures. The European Data 560

Protection Board’s Guidelines on the adoption and implementation of Article 25 further clarify 561

that the reference to the “state of the art” obligates organizations to remain current with 562

technological developments in privacy and security, noting that data controllers must “have 563

knowledge of and stay up to date on technological advances; how technology can present data 564

protection risks or opportunities to the processing operation; and how to implement and update 565

the measures and safeguards that secure effective implementation of the principles and rights of 566

data subjects taking into account the evolving technological landscape” [40]. 567

1

GDPR is retained in U.K. law as the “UK GDPR,” although in light of Brexit, the U.K. has independent authority to keep the

regulatory framework under review. As of this writing, the post-Brexit amendments to U.K. GDPR, as reflected in the relevant

“Keeling Schedule,” do not include any changes to the text of Article 25 of the U.K. GDPR, which is identical to the text of

Article 25 of the E.U. GDPR [38].

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

15

The GDPR data minimization and purpose limitation principles reflected in Articles 25 and 32 568

and the attendant liability risks for payment service providers could create an incentive for the 569

adoption of emerging technologies that obviate the data sharing upon which open banking is 570

currently premised. For example, certain verifications and aggregate computations commonly 571

performed by transferring customer data from ASPSPs to TPPs through the use of open APIs 572

could instead be performed using cryptographic techniques that do not require a TPP to access, 573

store, or process customer data in unencrypted form at all (e.g., secure multi-party computation 574

[SMPC], zero-knowledge proofs [ZK], private set intersections [PSI], homomorphic encryption 575

[HE], or hardware-based solutions that rely on trusted execution environments). By reducing the 576

amount of data shared in the open banking ecosystem in the first instance, the adoption of such 577

technologies could ease regulatory compliance burdens and reduce liability risks for ASPSPs and 578

TPPs. Moreover, this reduction in data sharing could provide an additional layer of protection for 579

consumer data, reducing the need to rely on potentially inefficient post hoc regulatory 580

enforcement remedies for consumer harm in the event of data misuse or improper exposure [41]. 581

Particularly in light of the Article 25 and Article 32 requirements for organizations to consider 582

the state of the art when determining and maintaining appropriate technological measures and 583

safeguards, such cryptographic technologies could find their way into standards as their adoption 584

increases both within the banking and financial services sectors and without. 585

4.2 Australia 586

In 2017, Australia introduced the Consumer Data Right (CDR) – an opt-in framework that grants 587

consumers the right to direct the sharing of their data held at regulated data holder institutions 588

(such as banks) with “accredited data recipients,” or third-party service providers, through APIs 589

[42]. The CDR is implemented by the Competition and Consumer (Consumer Data Right) Rules 590

2020 (CCCDR Rules), which are regulations under the legislative provisions of the Competition 591

and Consumer Act 2010 that govern “product data requests” related to data holder institutions’ 592

products, a consumer’s request for their own data, and requests for consumer data made on the 593

consumer’s behalf by an accredited third-party service provider [43]. Notably, similar to the 594

U.K.’s adoption of the Open Banking Standard discussed above, the CDR is accompanied by the 595

Consumer Data Standards – mandated by the CCCDR Rules and created by the Data Standards 596

Body within the Australian Treasury – which include technical and consumer experience 597

standards and detailed API specifications [44]. 598

The CDR became available for sharing consumer data in July 2020 when the four major 599

Australian banks (i.e., Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited, Commonwealth 600

Bank of Australia, National Australia Bank Limited, and Westpac Banking Corporation) were 601

required to begin sharing consumer data for their primary brands in compliance with the CCCDR 602

Rules and the Consumer Data Standards. An additional requirement to begin sharing consumer 603

data for their non-primary brands was scheduled for July 2021. Other deposit-taking institutions 604

have been required to begin sharing consumer data as of July 2021 for certain “Phase 1 products” 605

– including basic savings, checking, debit card, and credit card accounts – with a current 606

requirement to expand sharing to all products listed in the CCCDR Rules by February 2022 [43] 607

[45]. The listed banking sector products for which data sharing is governed by the CCCDR Rules 608

go beyond the basic payment services covered by PSD2 in the E.U. and the U.K. and include 609

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

16

certain “open finance” data, such as data for home and personal loan, mortgage, investment loan, 610

line of credit, and retirement savings account products [43]. 611

Participation in the CDR framework by FinTechs and other third-party service providers as 612

accredited data recipients appears to be progressing relatively slowly. As of this writing, the 613

Australian Government’s online list of CDR providers includes only six entities as “active” data 614

recipients – of which two are Intuit companies (Intuit Australia Pty Limited and Intuit Inc.) and 615

two are themselves banks (Commonwealth Bank of Australia and Regional Australia Bank Ltd.) 616

– with an additional seven currently accredited data recipients [46]. Given that the CDR does not 617

prohibit screen scraping, this relatively slow adoption could be at least partially explained by 618

third-party service providers’ reluctance to submit themselves to the considerably more rigorous 619

requirements of the CDR framework [47][48]. 620

Despite its comparatively later rollout, Australia’s CDR framework is viewed as a particularly 621

forward-looking approach to open banking. This view is due to the primary distinguishing 622

feature that sets the CDR apart from other countries’ approaches: although it is rightly seen as 623

providing the legal and regulatory foundation for open banking in Australia, the CDR is not 624

limited to the banking and financial services industry at all. Rather, the CDR provides a 625

framework for sharing consumer data across a multitude of economic sectors. The accompanying 626

standards reflect this broad vision with a particular emphasis on establishing consistent 627

representations of consumers across industries and a design approach focused on consumers 628

consenting to data sharing [48]. Banking is merely the first sector to which the CDR has been 629

applied. Next, it will be introduced to the energy sector, and subsequent application to the 630

telecommunications sector has been proposed [49]. 631

4.3 India 632

India’s open banking ecosystem has been facilitated by the government-driven development of 633

the “India Stack,” a collection of APIs that combine to form a digital infrastructure comprising 634

four technology layers [50]. 635

(1) The “presenceless layer,” controlled by the Unique Identification Authority of India 636

(UIDAI), relies on the Aadhaar authentication system introduced by the Indian 637

government in 2010, which is based on a 12-digit unique identity number. The Aadhaar 638

Auth API enables digital identity verification and authentication using a consumer’s 12-639

digit identity number to access stored biometric or demographic authentication data for 640

comparison [51]. 641

(2) The “paperless layer,” controlled by India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information 642

Technology,” facilitates the electronic storage and retrieval of documents linked to a 643

consumer’s digital identity and incorporates Aadhaar eKYC, an electronic know-your-644

customer service based on the aforementioned Aadhaar authentication system [52]; 645

eSign, an API-based digital document signature service facilitated by third-party service 646

providers licensed under India’s Information Technology Act ([53]); and DigiLocker, a 647

digital locker service that can be linked with a consumer’s Aadhaar identity number or 648

mobile number [54]. 649

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

17

(3) The “cashless layer” is controlled by the National Payments Corporation of India 650

(NPCI), a non-profit organization overseen by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). A 651

primary component of the cashless layer is an electronic payments network with 652

interoperability between banks and third-party service providers afforded by the Unified 653

Payments Interface (UPI), an open API standard with a standardized payments markup 654

language [55]. 655

(4) Finally, the “consent layer,” controlled by the RBI, manages data sharing subject to a 656

consumer’s consent. A key component of the consent layer is the Data Empowerment and 657

Protection Architecture (DEPA), a public-private effort to provide a technical and legal 658

framework for consumers to control and consent to sharing their data. Introduced as a 659

draft policy by the Indian Government public policy think tank NITI Aayog, the DEPA 660

launched in the financial sector in 2020, overseen by the Ministry of Finance, RBI, and 661

various government regulators. Similar to Australia’s CDR, the DEPA framework for 662

data sharing and consent is intended to apply beyond financial services to other sectors, 663

including health services and telecommunications [56]. 664

The 2020 introduction of DEPA reflects a recent focus on privacy in Indian open banking and 665

the digital data ecosystem of the India Stack more generally. This heightened focus was perhaps 666

motivated by early complications for the India Stack posed by privacy issues centered on the 667

Aadhaar authentication system underlying the India Stack [55]. In particular, a series of court 668

petitions challenging the mandatory use of the Aadhaar identification number as a violation of 669

individual privacy rights led to a 2018 Indian Supreme Court decision that, while upholding 670

mandatory use of Aadhaar for certain government purposes, curtailed the mandatory use of 671

Aadhaar authentication by private entities on constitutional grounds. This decision created 672

significant uncertainty around the legality of Aadhaar-based eKYC by banks, with some initially 673

believing that the Supreme Court ruling had effectively banned any use of Aadhar by private 674

companies for eKYC [57][58]. Eventually, however, the RBI allowed private banks to access the 675

Aadhaar service for KYC purposes but with an additional requirement of customer consent to 676

such use [59]. In response to calls for India to establish a clear legal and regulatory framework 677

for privacy protection, the Personal Data Protection Bill was introduced in the Indian Parliament 678

by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology in December 2019 [60]. 679

Within this privacy- and consent-focused environment, the DEPA framework of the India 680

Stack’s “consent layer” can be distinguished from other open banking standards by the central 681

role played by third-party intermediaries known as “consent managers” (CMs). In the basic 682

DEPA model, communications by all parties related to sharing a consumer’s data held at a data 683

controller (such as a bank) with a third-party service provider (such as a FinTech) pass through 684

the CM as an intermediary. The consumer communicates their consent to the CM, and a data 685

request from the third-party service provider is sent to the CM, who in turn relays the request to 686

the data controller, and – subject to the consumer’s consent – the consumer’s data responsive to 687

the request is sent from the data controller to the CM to the third-party service provider using an 688

end-to-end encrypted data flow [56]. The August 2020 version of NITI Aayog’s draft policy for 689

DEPA characterizes this reliance on CMs as a point of superiority to the U.K. Open Banking 690

Standard, at least in the Indian open banking ecosystem, noting that the U.K.’s lack of 691

“unbundling of the institution collecting data and the institution collecting consent … may not 692

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

18

work to address India’s scale and diversity.” The draft policy asserts that “[t]o reach [its] full 693

population, [India] will need multiple institutions specialized in consent management innovating 694

to provide multiple modes of obtaining informed consent (for example various form factors – 695

audio, visual or video, or assisted with an agent).” However, it does not appear to provide a 696

substantial explanation for why dedicated CM intermediaries, as separate parties in consent and 697

data flows, are necessary or provide a superior model in the Indian ecosystem or in open banking 698

more generally [61]. 699

4.4 United States 700

Thus far, the approach to open banking in the United States has been almost entirely market 701

driven. Although the U.S. has been a leading technological pioneer in many of the novel services 702

that open banking provides – with account-aggregation FinTechs such as Yodlee, Finicity, and 703

CashEdge (all of which have since been acquired by other entities) founded as early as 1999 – it 704

has lagged behind other countries in developing a full-fledged open banking ecosystem. 705

In contrast to the heavily regulation-driven approaches of nations like the U.K., E.U. member 706

states, and Australia and the hybrid approaches that incorporate public-private partnerships like 707

that of India, the most significant efforts toward API-based open banking in the U.S. have come 708

from the financial services industry itself, with participation from both FIs and FinTechs 709

[11][62]. The Clearing House (TCH) – the U.S.’s oldest banking association owned by 24 of the 710

largest U.S. commercial banks – has created a “model data access agreement” to streamline the 711

negotiation of contractual data access and data sharing agreements between FIs and FinTechs 712

[63]. 713

From the technology side, the leading standards initiative is the Financial Data Exchange (FDX) 714

consortium – a non-profit independent subsidiary of the Financial Services Information Sharing 715

and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC) that seeks to “unify” the financial industry around a common, 716

interoperable, and royalty-free standard for the secure access of user permissioned financial 717

data,” known as the FDX API [64]. In 2019, the Open Financial Exchange (OFX) consortium, 718

the other leading industry API standardization effort at the time, joined FDX as an independent 719

working group [65]. Although the FDX API is based on JSON data serialization [66] and the 720

still-available OFX API employs XML serialization [67], FDX has stated that existing versions 721

of the OFX standard will continue to be supported and that “users of OFX will have assistance to 722

migrate to the FDX API standard” [64]. FDX’s membership includes numerous FIs, FinTechs, 723

card networks, and technology companies. Although the FDX API specification is not openly 724

available, non-members can access the specification by registering with FDX and accepting an 725

FDX Intellectual Property Agreement [66]. In addition to FDX, the National Automated Clearing 726

House Association (NACHA) has established the Afinis Interoperability Standards group to 727

advance API and other financial-service standards. Although smaller than FDX, Afinis’s 728

membership overlaps with that of FDX and includes all 12 regional banks of the U.S. Federal 729

Reserve [68]. 730

Preliminary efforts by the Department of the Treasury and the Consumer Financial Protection 731

Bureau (CFPB) have provided some measure of guidance and direction for the financial services 732

industry’s efforts to develop a U.S. open banking ecosystem. In July 2018, the Treasury issued a 733

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

19

report – “A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities: Nonbank Financials, 734

FinTech, and Innovation” – that specifically noted the significant security risks and liability 735

burdens of screen scraping and the potential for APIs to provide a more secure method of 736

accessing consumer financial data. Although the Treasury identified “a need to remove legal and 737

regulatory uncertainties currently holding back financial services companies and data 738

aggregators from establishing data sharing agreements that effectively move firms away from 739

screen-scraping,” it recommended that the best approach to such a transition for the U.S. market 740

would involve “a solution developed by the private sector, with appropriate involvement of 741

federal and state financial regulators” [69]. Despite the Treasury report’s lack of detailed 742

guidance, it is the only government articulation of “consumer protection principals” currently 743

cited by FDX as part of its online FAQ in response to the question of “[w]hat federal or state 744

regulations impact the FDX API standard” [64]. 745

Beyond the Treasury’s 2018 report, the CFPB has made some efforts to address open banking 746

and related developments as part of its regulatory mandate to implement Section 1033 of the 747

Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which requires FIs to make 748

consumers’ transaction and account information available “in an electronic form usable by 749

consumers” and is arguably the provision of U.S. legislation most salient to facilitating open 750

banking [65]. In October 2017, the CFPB issued the “Consumer Protection Principles: 751

Consumer-authorized financial data sharing and aggregation” report, which articulated a set of 752

non-binding principles that were explicitly not intended to interpret or provide guidance on 753

existing laws and regulations. These principles addressed aspects of financial data sharing 754

including transparency; consumer access, control, and informed consent; security; dispute 755

resolution for unauthorized access; and accountability mechanisms for risks, harms, and costs 756

[70]. Although the CFPB Principles were not binding, the TCH Model Data Access Agreement 757

was designed to align with the Principles [63]. In October 2020, the CFPB issued an Advance 758

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) for Section 1033. The questions asked in the ANPR 759

and the public comments addressed issues relevant to open banking, including calls in the public 760

comments for CFPB implementation of strong privacy and security protections and for data-761

sharing standardization through open APIs. However, in view of the narrow scope of Section 762

1033, the CFPB’s ability to establish an open banking ecosystem through regulatory authority 763

remains unclear [65]. 764

The current lack of specific guidance or standards for the U.S. has led to a degree of uncertainty 765

in U.S. efforts to develop open banking, particularly around issues of privacy and security. For 766

example, FIs have significant liability concerns about sharing high-risk data, such as account 767

numbers or other personally identifiable information, as well as competitive concerns over 768

sharing proprietary information about FI products and services, whereas account aggregators 769

typically argue in favor of consumers’ ability to decide whether or not such data are shared [12]. 770

Moreover, in the absence of comprehensive adoption or mandated use of common API standards 771

for the exchange of financial data, screen scraping remains prevalent in the U.S. digital financial 772

services market [12][65]. This continued practice creates a heightened security risk for the 773

payment ecosystem, particularly in an environment where – according to research conducted by 774

TCH in 2019 – 80 % of consumers were unaware that they were not actually logging into their 775

FI’s website but rather providing login credentials to a TPP for the purpose of scraping [12]. 776

Although there is a general appreciation within the U.S. financial services industry of the 777

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

20

benefits – even the necessity – of adopting an open banking model, the lack of clear consensus 778

regarding how to implement such a model (whether mandated by laws and regulations or reached 779

independently by the industry itself) has arguably been a significant obstacle to the realization of 780

a U.S. open banking ecosystem. 781

4.5 Other Countries 782

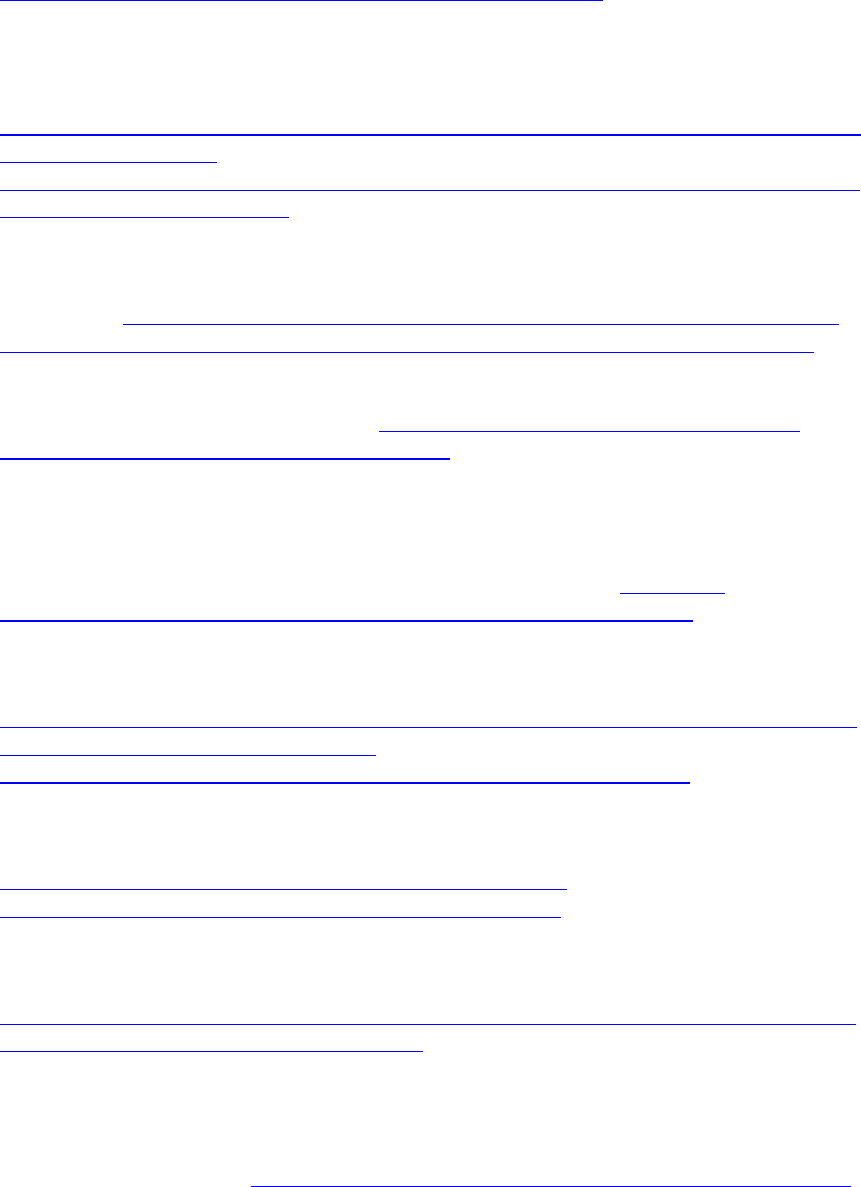

Various countries have begun significant work towards OB. A brief summary of OB initiatives 783

around the world is given in Table 2. 784

Table 2 - Summary of OB initiatives around the world 785

Region

OB Initiatives

Africa

• NA

Asia

• 2014, Singapore, Smart Nation Singapore

• 2016, India, Unified Payments Interface

• 2016, South Korea, KFTC Developer Platform

• 2016, Thailand, BOT Regulatory Sandbox

• 2017, Japan, Banking Act

• 2019, Hong Kong SAR, Open API Framework

• 2020, India, Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture

• 2020, Bahrain, Open Banking Framework

Australia

• 2017, Australia, Consumer Data Right

• 2018, Australia, Data Sharing Compliance

• 2018, New Zealand, Payments NZ

• 2020, Australia, New Payments Platform

Europe

• 2018, U.K., Open Banking Implementation Entity

• 2018, E.U., Payment Services Directive

• 2020, Turkey, Payment Law

• 2020, Russia, Recommendatory Standards for Open Banking

North

America

• 2018, Mexico, Fintech Law

• 2018, Canada, Consumer Directed Finance

• 2019, U.S., CFPB principles UST report

South

America

• 2019, Brazil, Open Banking Framework

• 2020, Chile, Financial Portability Act

A brief discussion of some of these initiatives is provided below. OB efforts in the U.S. are 786

discussed in Section 4.5. 787

NISTIR 8389 (DRAFT) CYBERSECURITY CONSIDERATIONS FOR OPEN BANKING

T

ECHNOLOGY AND EMERGING STANDARDS

21

Mexico 788

Led by “The Fintech Law” in 2018, the implementation of OB in Mexico serves as inspiration 789

for other countries in Latin America. The law applies to almost all types of financial entities and 790

both transactional and product data, but it does not cover payment operations. 791

Brazil 792

The Central Bank of Brazil has been following a phased approach in implementing the “open 793

banking model” since it was published in 2019. It will be mandatory for large financial and 794

banking institutions with significant international activity and optional for others. The 795

implementation of the first phase occurred in early 2021 when the fundamental requirements for 796

the implementation of the law were disclosed. Phase 2, in which consumers will have an option 797

to share their data with the institutions they wish, is set to be implemented in July 2021. 798

Japan 799

Despite being among the first countries in Asia to establish its own OB framework in 2015, the 800

measures to adopt it have been versatile and focus mostly on partnerships between banks without 801

building API portals. For example, in 2017, three megabanks – Mizuho, Sumitomo Mitsui, and 802

MUFG – agreed on establishing a universal QR payment system. Another milestone was 803

recorded in 2018 when a QR code payment system called “Yoka Pay” was established as a 804

collaborative effort between Resona Banks, Fukuoka, and Yokohama. 805

Singapore 806

The Monetary Authority of Singapore has introduced API Exchange (APIX), which provides a 807