MONITORING

& EVALUATING

GROWTH

LEARNING

PROGRESSION

TASKS &

ITEMS

INTERPRETATION

Using a Learning Progression

Framework to Assess and

Evaluate Student Growth

April 2015

NATIONAL CENTER FOR THE IMPROVEMENT

DOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE

CENTER FOR ASSESSMENT DESIGN

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO, BOULDER

Derek C. Briggs

Elena Diaz-Bilello

Fred Peck

Jessica Alzen

Rajendra Chattergoon

Raymond Johnson

Foreword

The complex challenges of measuring student growth over the course of a school year have become familiar to

anyone working to improve educator evaluation systems. Recent legislation in many states has postponed or

scaled back the use of student growth or outcomes within accountability frameworks, suggesting that they

While we struggle to measure student growth in a valid and reliable way for the tested subjects, such as math

education. In the absence of state-mandated tests for the latter, many states and districts have begun to

measuring the extent to which each student has mastered them. There is no single way to design and

variety of models in use across the country. The authors of this paper, however, present what might be called

an alternative model of SLOs, a Learning Progression Framework

practices.

As the authors of this paper demonstrate, while some SLO models appear more promising than others, their

de facto

system of unequal access to grade-level content, and 3) despite their best intentions, they typically serve the

In light of these limitations, the authors demonstrate how the LPF model acknowledges the reality that

intended outcomes cannot, on their own, improve teaching and learning. In the Denver Public Schools, we are

implementing the LPF model based on a commitment to the idea that improvement of teaching and learning

will depend on the way teachers meet students’ individual needs along the path toward standards mastery. At

the risk of indicating the obvious: formative assessment and appropriate adjustments to instruction play an

In Denver, we have been working over the past two years to develop and implement an SLO model based on

learning progressions. At its core, the model is meant to be authentic to everyday cycles of formative

assessment and instructional shifts, even as we intend to use it for summative accountability purposes. We

structures and systems for teacher collaboration, distributed leadership, and a careful balance of teacher

autonomy and quality assurance for the larger system. And yet, we have seen some early successes worth

celebrating, which include: teachers’ deeper knowledge of the standards in their subjects, the development of

shared goals and more consistent collaboration among teams of teachers, and more intentional uses of

assessment to support instructional planning and student learning.

A deeper understanding of assessment is critical at a time when standardized and summative tests are

becoming increasingly prevalent and controversial. The LPF strives to put educational assessment where it

belongs: close to the curriculum, the instruction, and the student. When we think in terms of learning

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth i

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth ii

rigorous tasks assigned to students throughout the school year, and systematic observations of student

its necessary conditions.

that we would promote their use in classrooms even if there were no legislation requiring student growth

measures. This is because SLOs, when implemented within the Learning Progression Framework, capture the

essence of high-quality instruction, pushing us to ask fundamental questions like the following: What is most

important for my students to know and be able to do? What do my students know right now, and how do I know

that? What should I do to meet my students’ needs? If we can answer these questions with increasingly greater

most importantly, of students in their day-to-day learning.

Michael I. Cohen, Ed.D.

Assessment Support Manager

Department of Assessment, Research & Evaluation

Denver Public Schools

Denver, CO

I. Overview

The metaphor of growth is central to conversations about student learning. As students advance from grade

to grade, one naturally expects that what students know and understand about the world and about

themselves is becoming more sophisticated and mature. Of course, there are many factors that could

But how does one know both what and how much students have learned over a delimited period of time in

some content area? Although a well-designed assessment may help to answer the question of what students

seem to know and understand, no single test can support inferences about how much this has changed over

time. Furthermore, even when students are assessed periodically, inferences about growth may remain

elusive if the content on the assessments is also changing. Finally, if these assessments are not well aligned to

what is taught as part of a school’s curriculum, the picture of student growth being presented can easily be

characterize growth numerically in a manner that leads to valid and reliable inferences is extremely

challenging.

This challenge is becoming all the more apparent as a rapidly growing number of states and school districts in

the United States seek to incorporate evidence of student growth into formal evaluations of teachers under

and debate has surrounded the use of statistical models for this purpose, only about one third of classroom

teachers teach students for whom state-administered standardized tests are available as inputs into these

being gathered through the development and evaluation of student growth through “Student Learning

SLOs typically involve a process in which teachers establish measureable achievement goals for their students,

assess students at the outset of an instructional period and then establish targets for student growth over the

duration that period. A central impetus for this report is the belief that SLOs will only be able to support

sound inferences about student growth if they have been designed in a way that gets educators attuned to the

right motivating questions.

• What do I want my students to learn?

• What do my students know and understand when they arrive in my classroom?

• How is their knowledge and thinking changing over time?

• What can I, and other teachers at the school, do to help them learn?

• What evidence do I have that my students have demonstrated adequate growth?

Inferences about student growth that account for such questions need not only learning objectives but a

framework that structures objectives into a progression of student learning. In this report we introduce a

learning progression framework (LPF) that applies innovative thinking about educational assessment to better

directly anticipates the questions posed above. In addition, it can support a process that is much more

encompassing than the de-facto use of SLOs for teacher evaluation. Indeed, in this report we show that SLOs

can be cast as a special case within an LPF.

Importantly, an LPF has three features that are always present irrespective of the content domain. First, a

critical condition for operationalizing the framework is to have teachers work collaboratively to identify a

Learning Progression (LP) within and, ideally, across grades or courses. Collaboration in this matter requires

that teachers clearly establish what it means to say that a student has shown “adequate” growth in a

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 1

criterion-referenced sense. Second, an LPF emphasizes growth toward a common target for all students.

teacher collaboration is explicitly oriented toward the analysis of student work. This work might range from

multiple-choice answers on a standardized test, to responses on an open-ended essay, or to videos of students

carrying out a classroom project. Teachers use this evidence to document the variability in how students

respond to assessment activities, make distinctions among students with respect to the sophistication of their

responses, and come up with teaching strategies that can best support the students with less sophisticated

responses and further challenge the students with more sophisticated responses. An LPF focuses attention on

that teachers who think in terms of learning progressions are often just as interested in the process a student

uses to solve a task as they are in whether an answer to the task is correct. This also means that there is a

focused interest in understanding the space between the two points of “getting it” and “not getting it” as a

means for locating and understanding student misconceptions and strengths in solving a task.

In this report we will argue that learning progressions are a valuable framework for characterizing and

elucidating the objectives, targets, or goals of instruction. The terms objectives, targets and goals are all

“Student Learning Objective” is its formalization and standardization as a process that is intended to meet

public monitor this growth for accountability purposes. There is a tension between these two needs, as the

high-stakes nature of accountability consequences has the potential to undermine the use of SLOs for

the collaborative processes we describe in what follows, any subsequent SLO that is generated from this

framework will have a greater chance of securing teacher buy-in as something that is authentic to what they

value in the classroom and something that they can control.

states. We do so in order to highlight common threats to the validity of SLOs. We then present the LPF as a

possible solution to these validity threats.

II. Student Learning Objectives

Due in large part to federal requirements that mandate evidence of growth in student achievement to be

funding and/or submitted an Elementary and Secondary Education Act waiver now use SLOs as a key

by RTTT states and districts for measuring student growth for non-tested subjects because only a minority of

teachers teach in subjects for which state-administered standardized tests are available, SLOs in many places

now apply to both tested- and non-tested subjects and grades Hall, Gagnon, Marion, Schneider & Thompson

learn.

year-long).

• An evaluation of each teacher based on the proportion of the teacher’s students who have met their growth

targets by the end of the instructional period.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 2

The implementation of these common SLO elements varies across states and districts depending upon the

degree of centralization and comparability desired in the set of learning goals used across all teachers, the set

of data sources used to support the process, and the methodology used to specify student growth targets and

examples from two states, Georgia and Rhode Island. We consider these two states because they used

contrasting approaches and policies in designing the SLO process. In Georgia, school districts, also known as

local education agencies (LEAs), dictate which assessments should be used by teachers and how student

growth targets should be set. The state provides guidelines on how teacher ratings are assigned based on the

extent to which growth targets are met by students. In Rhode Island, the state allows teachers to select their

own assessments to evaluate students on their learning objective and to set the growth target expectations

for their students. Although Rhode Island provides guidance on two approaches for scoring each SLO, school

in terms of the constraints they place upon teacher enactment of SLOs, the SLO process in both states

involves all the same elements. After presenting the SLO process for each state separately, we call attention to

what we view as problematic aspects of these common elements.

GEORGIA

In Georgia, only teachers in non-tested subject areas are eligible to submit an SLO. For any given SLO, options

for learning objective statements, assessments, and growth targets are established by grade and content area

come from the administration of a “pre-test” at the beginning of the school year and “post-test” near the end

of the year. In most cases the same test is given twice, but this is not a mandated requirement. The state

gives school districts considerable discretion in choosing assessments that would be eligible for use as a

pre-test and post-test. These may range from commercially developed tests to locally developed performance

tasks.

of approaches that could be used to set growth targets, one that establishes individualized student targets,

expected growth targets in every course and grade. This is illustrated in Figure 1 for an SLO in reading

expressed in a percentage-correct metric. In this example, a student will have demonstrated expected growth

multiple-choice or short open-ended test items that can be readily scored as correct or incorrect. Teachers

would use the second approach with assessments that consist of performance-based tasks or a portfolio of

student work that is scored holistically.

In either of these two approaches, a student’s performance from pre- to post-test is subsequently placed into

one of three categories: did not meet growth target, met growth target, exceeded growth target. The

frequency counts of students in each category are then tabulated for the teacher of record and converted into

a percentage out of total. This forms the basis for scoring teachers according to an “SLO Attainment Rubric,”

an example of which is provided in Figure 3. These rubrics are used to categorize teachers into one of four

The choice of thresholds that determine teachers’ placements in each category is set by the state and remains

the same, irrespective of a teacher’s school district, grade or subject.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 3

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 4

FIGURE 1: SAMPLE SLO USING INDIVIDUALIZED TARGETS

SLO Statement Example:

vocabulary and comprehension skills as measured by the Mountain County Schools Third Grade

Reading SLO Assessment. Students will increase from their pre-assessment scores to these post-

assessment scores as follows:

The minimum expectation for individual student growth is based on the formula which requires each

student to grow by increasing his/her score by 35% of his/her potential growth.

sight reading and noting music skills as measured by the Mountain County Schools Intermediate

Chorus Performance Task. Students will increase from their pre-assessment scores to these post-

assessment scores as follows:

Students who increase one level above their expected growth targets would be demonstrating high

growth.

a developmentally appropriate project or assignment based on the SLO assessment’s content.

Source: Georgia Department of Education, 2014 [see 2014-2015 SLO Manual at

]

Source: Georgia Department of Education, 2014 [see 2014-2015 SLO Manual at

]

LEVEL IV

In addition to meeting the

requirements for Level III

LEVEL III

Level III is the expected level

of performance

LEVEL II LEVEL I

The work of the teacher

results in exceptional

student growth.

demonstrated expected/

high growth on the SLO.

The work of the teacher

results in appropriate

student growth.

demonstrated expected/

high growth on the SLO.

OR

demonstrated expected/

high growth on the SLO.

OR

demonstrated expected/

high growth on the SLO.

The work of the teacher

does not result in

appropriate student

growth.

demonstrated expected/

high growth on the SLO.

The work of the

teacher results in

minimal student growth.

demonstrated expected/

high growth on the SLO.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 5

FIGURE 3: SAMPLE “SLO ATTAINMENT RUBRIC” FOR EVALUATING TEACHERS

Source: Georgia Department of Education, 2014 [see 2014-2015 SLO Manual at

]

RHODE ISLAND

In contrast to Georgia, Rhode Island’s SLO system provides considerable latitude to teachers in specifying the

learning goal, selecting student assessments, and setting targets for individual or groups of students.

critical knowledge and skills that are needed to be successful in the next grade level. Collaboration among

teachers is an expected aspect of the SLO process in Rhode Island. The state encourages teachers to work in

teams to select important learning goals and select or develop tasks to assess students both over the course

of the academic year and at its culmination.

Teachers are expected to consult a variety of data sources that can vary from teacher-made assessments to

beginning of the course and to later make an end of the course assessment of their students. Teachers

second approach, and Figure 5 presents an example of each approach.

similarly, only one target is set for one group of students (see column 1 of Figure 5). In the third target setting

approach, individual targets are assigned to individual students on SLO assessments selected. Column 3 in

Figure 5 presents one example of how individual targets are set for each student using just one data source.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 6

Source: Rhode Island Department of Education, 2014 [see Measures of Student Learning - Teacher at

http://www.ride.ri.gov/TeachersAdministrators/EducatorEvaluation/GuidebooksForms.aspx]

Some students are entering the

course without necessary

prerequisite knowledge or skills.

TIER 1 TARGET

Some students are entering the

course with the necessary

prerequisite knowledge or skills.

TIER 2 TARGET

Some students are entering the

course with prerequisite

knowledge or skills that exceed

what is expected or required.

TIER 3 TARGET

WHOLE GROUP TARGETS TIERED TARGETS INDIVIDUAL TARGETS

One target for all students

This works best when:

• Baseline data show that all

students perform similarly

• The course content requires a

certain level of mastery from

all students in order to pass/

advance (e.g., a C&T course in

Plumbing)

• It is necessary for all students to

work together (e.g., orchestra,

theater, dance).

Dierent targets for groups of

similar students

This allows for projecting

achievement for students who are

at, above, or below grade level.

Individualized targets for

each student

This can work well in Special

Education settings and/or when

class sizes are small.

EXAMPLES:

State Cosmetology Exam.

EXAMPLES:

the baseline writing prompt will

monthly writing prompts.

the baseline writing prompt will

monthly writing prompt.

EXAMPLES:

Students will meet individual

targets on Fountas & Pinell guided

reading levels.

Student 1 will reach a level O

Student 3 will reach a level M

Student 5 will reach a level N

FIGURE 5: SAMPLE “SLO ATTAINMENT RUBRIC” FOR EVALUATING TEACHERS

Source: Table adapted from Rhode Island Department of Education, 2014 [see Measures of Student Learning - Teacher at

http://www.ride.ri.gov/TeachersAdministrators/EducatorEvaluation/GuidebooksForms.aspx]

Similar to Georgia, in Rhode Island students are placed into three categories as a function of whether they

have not met, met, or exceeded their growth targets. Teachers are then placed into four categories that hinge

upon the proportions of students in each category. It is left to the discretion of school districts to establish

SUMMARY

The SLO processes in Georgia and Rhode Island are similar in the sense that they involve the same elements

student performance. Georgia is an example of a “top-down” SLO process in which decisions about learning

goals, assessments, and growth targets are all made by school districts and the state. Rhode Island is an

example of a “bottom-up” SLO process in which teachers are expected to collaborate in the writing of learning

goals, choosing and/or developing assessment tasks, and setting growth targets. In both states, thresholds

for scoring teachers on the basis of the proportion of their students who meet or exceed SLO targets are

established by LEAs.

Regardless of the degree of centralized control exercised upon the SLO process, states and districts face

common challenges that are potential threats to the validity of the SLO process in the long-term. Below, we

COMMON THREATS TO THE VALIDITY OF SLOS

1. Murky denitions of “growth”

Because SLOs are supposed to represent growth achieved by students between the beginning and the end of

an instructional period of interest, all states have devised various approaches to quantify and to classify the

level of growth achieved by each student or groups of students. However, for many places using a pre-test

and post-test approach to compare baseline and end-of-course location of students, including Georgia and

Rhode Island as described above, the answer to the question of “how much” students have learned remains

narrow the curricular focus to the material that will be tested. Perhaps most importantly, rules for

establishing the adequacy of growth from pre- to post-test are typically arbitrary (e.g., Georgia’s formula

explanations for what it means to show a year’s worth of growth have been thoughtfully established.

2. Dierent targets are set for dierent students

targets and expectations are set for students located at varying baseline starting points. Although the

intention behind setting these targets is to ensure that realistic expectations for students with varying degrees

of preparedness are set, several challenges have emerged with this approach. In some places (e.g., Hawaii,

Rhode Island, North Carolina and Ohio), teachers are asked to estimate how many students will reach

students at the beginning of the school year or course, and the percentage of students meeting the expected

targets is used to derive teacher ratings for the SLO. Although this approach was developed with the intention

of deferring to a teacher’s professional judgment to determine where students should be located on the

learning objective, it is premised on the assumption that teachers can accurately predict each student’s

performance. It also sets up a potentially perverse incentive for teachers to lower standards for lower

achieving students. The resulting outcome of this approach is that although these targets are supposed to be

informed by baseline data, the expectations set at the beginning of the year can take on a more “arbitrary”

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 7

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 8

feel with some teachers feeling resentful of those who set consistently low targets for students and others

feeling frustrated at never reaching the predicted targets set for their students (Briggs, Diaz-Bilello, Maul,

underserved populations, are given opportunities to learn and access higher standards. Although we agree

learning goal or objective, labeling movements short of the objective as “met” may not set the right

expectations or signal for these students from an equity standpoint.

3. Accountability concerns trump instructional improvement

Fundamental to any theory of action behind the use of high-stakes accountability is the belief that systemic

improvement will come from changes to instructional practice, and much of the rhetoric describing the SLO

process places considerable emphasis on this for formative purpose. For example, at the Georgia Department

of Education website

1

, SLOs are characterized as both a tool to increase student learning and provide evidence

that will factor into its educator evaluation system (“The primary purpose of SLOs is to improve student

learning at the classroom level. An equally important purpose of SLOs is to provide evidence of each teacher’s

instructional impact on student learning.”). Similarly, in Rhode Island, the Department of Education has

produced a video that emphasizes the ambition that SLOs should be a useful tool that stimulates classroom

practice and teacher collaboration

.

However, in many states, including Georgia and Rhode Island, “pre” and “post” assessments become the sole

focus of the SLO process. This encourages teachers to set narrow goals that can be easily assessed and to

attend only to post-assessment results. Ultimately, the SLO process becomes a compliance activity in which

teachers are motivated by accountability concerns, rather than the SLO process being a driver of instructional

Given these three threats to the current state of SLOs, what can be done? Below we introduce a novel

approach with the potential to address these threats that we call the Learning Progressions Framework (LPF).

The LPF we introduce in the following section was developed as part of the Learning Progressions Project. This

pilot project involved a two-year collaboration with three Denver Public Schools (one elementary, one middle,

when teachers are being asked to implement SLOs across grades within a common subject and within grades

teachers implement SLOs at our pilot sites. Findings from the implementation work are captured under a

1

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 9

III. The Learning Progression Framework

THE ASSESSMENT TRIANGLE

The LPF was directly inspired by the idea of the “assessment triangle” presented in the National Research

argument was advanced that any high-quality assessment system will always have, at least implicitly, three

elements: a theory of student cognition or of how students learn (e.g., a qualitatively rich conception of how

students develop knowledge), a method for collecting evidence about what students know and can do, and a

method for making inferences from this evidence (e.g., a sample of student answers to assessment tasks) to

that which is desired (the ability to generalize knowledge and skills in applied settings). In our pilot project in

Denver Public Schools, we worked with teachers to develop learning progressions (LPs) that served as a

starting point for building a theory of student cognition. With this in mind we see the LPs as central to our

approach for assessing student growth.

represents a continuum along which a student is expected to show progress over some designated period of

expected to master within a given content domain by taking a particular course (or courses) in school. In the

empirically grounded and testable hypotheses about how students’ understanding of core concepts within a

subject domain grows and become more sophisticated over time with appropriate instruction (c.f., Corcoran,

Students are expected to start at one position on the LP and then, as they are exposed to instruction, move to

elicit information about what a student appears to know and be able to do with respect to a given LP of

interest. Finally, the information elicited from items, tasks and activities has to be converted into a numeric

and systematic basis for monitoring and evaluating student growth.

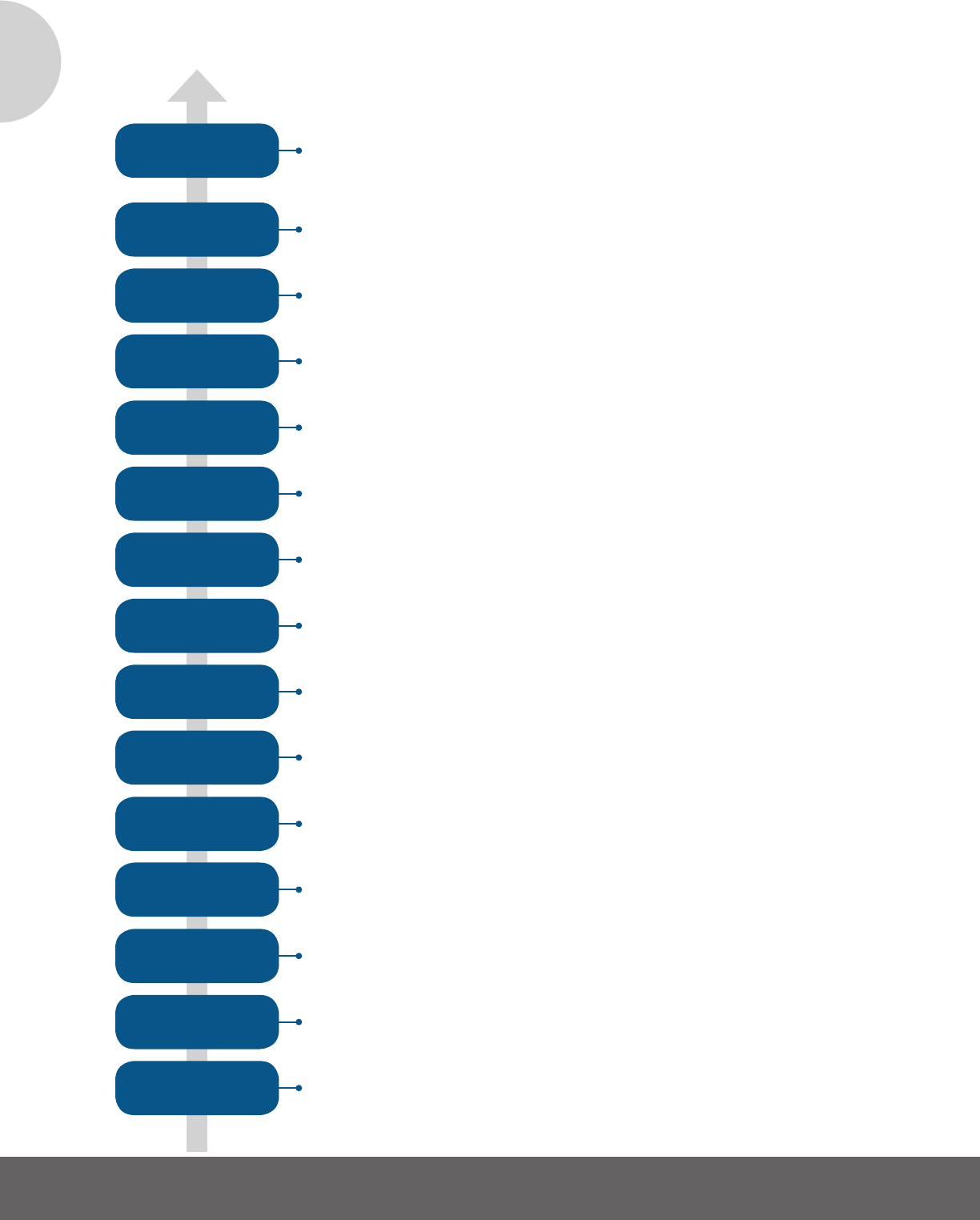

Monitoring

& Evaluating

Growth

Learning

Progression

Tasks &

Items

Interpretation

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 10

OVERVIEW OF THE LEARNING PROGRESSION

FRAMEWORK FOR ASSESSING STUDENT GROWTH

drawing upon aspects of the LPF that were implemented in our work with three pilot schools in the domain of

mathematics.

STEP 1: CHOOSE AN LP AND ESTABLISH A LEARNING OBJECTIVE RELATIVE TO THIS LP.

“What are the most important things you expect your students to know and be able to do by the end of the

school year?” This usually results in a wide variety of answers that vary in grain size. The choice, whether it is

made by a single teacher or a team of teachers and/or curriculum specialists, should be motivated by the

following questions:

• What goals do you have for your students?

• How are these goals related to your state or district’s content standards and the scope and sequence of your

curriculum?

• How do these goals relate to what students were learning in previous grades/courses? How do they relate to

what students will learn in future grades/courses?

or a school year?

• What do success criteria look like for students on these learning objectives (i.e., how will you know it when

you see it?)

process and make

improvements

1. Choose LP,

establish learning

goal

with respect to

movement across

levels of the LP

location on LP,

score student

growth

3. Establish

baseline location

on LP

“student focus

sessions” and

monitor growth

Importantly, a learning objective should be written such that it is more than a list of facts that students

what students should know but what they should be able to do. As a concrete example, the Common Core

State Standards for mathematics (www.corestandards.org/Math/Content/) are written with respect to

with a subset of mathematical practices (e.g., “Students will be able to use place value understanding and

properties of operations to solve problems that involve multi-digit arithmetic.”).

The Ideal Approach: An Across-Grade Learning Progression

The ideal is to have teachers working collaboratively in teams to establish an LP that tracks the same big

picture concept over multiple grades. For some concepts in math, science and English Language Arts,

LP is adopted, it will still need to be customized to a district’s local context. For example, we worked with

middle school mathematics teachers to adapt a published LP on equi-partitioning and proportional reasoning

When there is not a pre-existing research-based LP (as will commonly be the case), a new one would need to

be created. These created LPs will not match the research rigor or depth of research-based LPs. However, they

are still valuable because they are rooted in state standards and teachers’ experience, and as they are put in

CCSS for mathematics provides an organization of standards across grades in domains such as Operations &

A cluster of standards within any one of these domains, crossed with standards for mathematical practice

(i.e., modeling, reasoning) could be chosen as the starting point for elementary or middle school learning

statements about what students should know and be able to do by the end of an instructional period. Of

course, standards documents for mathematics lend themselves most readily to the formation of an LP that

crosses grades because the content tends to have a hierarchical structure. In the following section we discuss

how the LPF can still be applied in a context in which progressions of content across grades are more tenuous.

at one of our pilot sites chose the big-picture topic of place value (within the domain of number & operations

in base ten in the CCSS) as a focal area that represented a critical foundation students would need in order to

learn math at a higher level upon entry to middle school.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 11

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 12

LEVEL 15

LEVEL 13

LEVEL 11

LEVEL 9

LEVEL 7

LEVEL 5

LEVEL 3

LEVEL 14

by the end of grade 5

LEVEL 12

LEVEL 10

by the end of grade 3

LEVEL 8

LEVEL 6

by the end of grade 1

LEVEL 4

LEVEL 2

LEVEL 1

PLACE VALUE: WHAT STUDENTS KNOW & CAN DO

model math. Students can write and evaluate numerical expressions with whole number exponents.

Partial Understanding/Messy Middle

Partial Understanding/Messy Middle

Partial Understanding/Messy Middle

Partial Understanding/Messy Middle

Partial Understanding/Messy Middle

Partial Understanding/Messy Middle

Students can read and write numbers from whole numbers that include decimals to thousandths with numerals

explain patterns in the placement of the decimal point when any given number is multiplied or divided by a

place using standard form, word form, and expanded form. Students will demonstrate understanding of what

number to 999. Round to nearest ten.

Students will be able to compose and decompose any two-digit number (11-99) into groups of tens and further

and symbols for greater than, less than, and equal to.

Students can compose and decompose numbers from 11-19 into ten ones and some further ones by using objects

correspondence. Students can separate up to 5 objects and can identify which group has more or less. Students

Students can count verbally up to 5. Students can count accurately between 1 and 5 objects with supports.

Students can recognize numbers 1 to 5.

Students can read and write numbers to millions using words, numbers, and expanded form. Round whole

numbers up to millions place and compare multi-digit whole numbers using comparison symbols. Students can

hundreds.

thousands place using standard form, word form, and expanded form. Students will demonstrate understanding

of what each digit represents. Round numbers to the hundreds. Apply extended facts to the tens place value.

mastered the place value concepts in the upper grade target, but their thinking about place value is clearly

in-between state as “the messy middle” because it represents a stage in which students may vary considerably

might be able to correctly compare two digit numbers using symbols by memorizing certain rules without

being able to decompose the numbers into combinations of tens and ones. This attention to subtle

of providing teachers with a useful basis for providing students with feedback and individualized instruction.

When an LP includes levels that span more than two grades, attention is focused on the changes in student

understandings that would be expected to take place across grade levels as students are exposed to

instruction targeted to certain core concepts. For a given teacher, it is still a priority to decide how to properly

characterize the student growth expected within their grade or

course. But for groups of teachers in collaboration, more can be

understood about student growth across grades. So we draw an

important distinction between an across-grade LP, and a course-

trajectory will be the same. But usually, teachers will choose some

criterion-referenced manner, where it is that students are expected

to start at the beginning of an instructional period, where they are

expected to end at the culmination of the instructional period, and

how much they have grown in between.

An LP Specic to a Single Grade or Course

We now attempt to generalize the LPF sketched out to this point

such that it could be employed by any teacher for any subject area,

with or without an LP that spans more than two grades. To do this

we need to introduce the following terms: the aspirational upper

anchor (i.e., the learning target), the aspirational lower anchor, and

the realistic lower anchor. The aspirational upper anchor for a

learning objective. Hence, so long as there are standards or goals

that a school, district or state has established for each subject and

grade, there should always be a basis for operationalizing a

meaningful aspirational target. The aspirational lower anchor

anticipated level of a student’s preparedness for the course. Often

lower anchor might represent a student who was a full year behind

knowledge and skills evident of students who arrive in a course

with the least amount of preparation.

The levels of this generic LP are illustrated in Figure 9. If a teacher

or team of content specialists can identify a learning objective, an

aspirational lower anchor, and a realistic lower anchor, it is possible

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 13

LEVEL 5

Student Learning Objective: Grade

of Learning Progression

Messy Middle: On the way to

mastery of the Upper Anchor

LEVEL 3

Aspirational Lower Anchor of

Learning Progression

Messy Middle: On the way to

mastery of the Aspirational Lower

Anchor

LEVEL 1

Realistic Lower Anchor of

Learning Progression: Where a

start at the beginning of the

instructional period

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 14

to create an LP to conceptualize student growth. Note that the levels of the LP could be tailored to topics in

articulate two levels below the aspirational lower anchor, the LP could be reduced to four levels rather than

come into the course with a background that exceeds the aspirational lower anchor, it would be possible to

given student to demonstrate would change.

The critical features of this step are threefold. First, it requires a criterion-referenced explication of what it

means for students to demonstrate growth during an instructional period. Second, it establishes a common

additional instructional support that is likely required to catch them up. Third, it places attention on the fact

that there are levels of student understanding and reasoning that fall in between the LP anchors (“the messy

middles”).

In the remaining steps of the LPF that follow, we will assume that a teacher has established a course or

growth would only encompass a subset of these levels as in Figure 9. Hence whether or not an across-grade LP

is available, the steps of the LPF that follow would remain the same.

STEP 2. DEFINE GROWTH WITH RESPECT TO MOVEMENT ACROSS LEVELS OF THE LP.

referenced meaning as the beginning and ending locations of students who follow the path envisioned in

levels anywhere within the trajectory.

negative or no growth

student who remains at the same level or moves backward, minimal growth

one level, aspirational growthexceeded

aspirational growth

growth is that growth can be captured anywhere along the trajectory, so that a student who moves from level

1 to level 3 is conceptualized as demonstrating a full year’s growth, even though, from a status perspective,

the student is not “at grade level.”

STEP 3: USE THE LP, ALONG WITH AN ASSESSMENT CHECK TOOL, TO IDENTIFY

PREEXISTING AND/OR CREATE NEW ASSESSMENT DATA TO ESTABLISH THE LOCATION

OF STUDENTS WITHIN LP LEVELS AT THE BEGINNING OF THE INSTRUCTIONAL PERIOD.

Choosing or Writing Assessment Items

The next step is to either pick or develop items (i.e., tasks, activities) that can be administered over the course

of the instructional period with an eye toward eliciting information about what students appear to know and

be able to do with respect to the big picture idea captured by the LP. A key consideration in relating student

performance on these assessments to LP levels is the quality of the items.

• Are the items well-aligned to the LP?

• Do they allow for varied means for students to express understanding?

• Are they written at the appropriate level of cognitive demand?

• Are the rubrics written so as to minimize inter-rater variance?

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 15

underlying LP is that no single item, unless it is a rather involved performance task, is likely to provide

approach, assessment items need to be written purposefully so that, collectively, they target multiple levels of

the LP. Even within a level, multiple items would need to be written that give students more than one

opportunity to demonstrate their mastery of the underlying concept. For many LPs, this will mean items need

to be written with an eye toward not just answering an item correctly but also the process used to answer the

item correctly. To go back to the place value example, a student may be able to identify which of two

three-digit numbers is larger without fully understanding how to compose and decompose a three-digit

numbers into hundreds, tens, and ones. The need for a “bank” of items that can distinguish students at

multiple LP levels points to another advantage of working in multi-grade vertical teams. Namely, if teachers at

aspirational learning target from the level below, an assessment could be assembled relatively easily by

pulling from the full bank of items across grades.

The above discussion has mainly focused on assessment items. When multiple items are assembled into an

assessment, one can ask questions about the quality of the overall assessment.

• Does the set of items cover all of the relevant levels in the LP?

• What is their cognitive complexity?

• Are there multiple items per level?

• Is the assessment fair and unbiased?

• Do student scores generalize over other types of parallel items that could have been administered, or other

teachers that could have done the scoring (in the context of constructed response items)?

To help teachers evaluate items and assessments vis-à-vis the considerations above, we collaborated with

teachers to develop rubrics for evaluating items and assessments. These rubrics, which we call “assessment

check tools” are available on the CADRE website (http://www.colorado.edu/education/cadre).

Establishing Baseline Locations of Students on the LP

bands” by summing up the total points earned, expressing these points as a percent of total, and then

happened to be very easy (or very hard), then students might all receive A and Bs (or Fs and Ds) even if they

A very carefully considered “mapping” needs to occur any time an assessment is administered for the purpose

of estimating a student’s level on a LP. The mapping must convert student scores or performance on

assessment items or performance task(s) into a location on the LP. This process is important because it

removes much of the arbitrariness associated with student scores and instead provides each score with a

meaning that is directly aligned to the descriptions present in the LP. In addition, aligning each assessment to

the LP eliminates the need to give a common pre-post assessment. Instead, assessments can be designed to

provide maximum information about a students’ presumed location (for example, relative to Figure 9 this

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 16

according to levels of the LP. But in other cases, when an assessment consists of many tasks and/or items,

One practical way to accomplish this is to follow the two step process below (for a more detailed example, see

1. Start by dividing student scores into bins, such that there is the same number of bins as there are levels in

scores in quartiles, etc.). This serves as a basis for grouping students who are likely to be relatively similar in

their overall performance, and serves as a tentative mapping from the assessment scores to the LP. The top

score group maps to the top LP level, the lowest score group maps to the lowest LP level, etc.

students in each score group to determine if the responses are in fact representative of the mapped LP level.

For the students in the top performing group, one question to be asked is whether the lowest score in this

bin is indicative of someone at the top level of the LP. And so on for each bin. If, for example, all students in

a teacher’s class have high scores, it would be possible that students in the top three score bins all get

mapped to the top level of the LP. In contrast, if all students have low scores, the top three score bins might

only be mapped to middle level of the LP.

There are two occasions when the mapping process described above will need to be used to place students

into LP levels. At the outset of the instructional period, in order to establish each student’s baseline location,

and at the end, to establish the amount of growth they have demonstrated relative to this baseline location.

from baseline to the end of instructional period. In each case, assessments should serve as only one piece of a

body of evidence that a teacher uses to place students. A practical approach for this is for teachers to consider

rene

assessment. For example, the teacher’s observations of a student throughout the year suggests that the

It should not require multiple sources of evidence to show a student begins the year at the aspirational lower

anchor. To ease the setting of benchmarks, it should be assumed students are at the aspirational lower anchor

and evidence should be considered to judge whether that assumption is sound.

STEP 4: MONITOR GROWTH AND ADJUST INSTRUCTION BY CONDUCTING “STUDENT

FOCUS SESSIONS” OVER THE COURSE OF THE INSTRUCTIONAL PERIOD.

Student responses to assessment items can be used to not only locate students on a learning progression, but

to facilitate changes to instruction. To accomplish this, we developed a process in which teachers meet

together to discuss student responses with the goals of (a) improving assessment items, and (b)

understanding student reasoning and using this understanding to design responsive classroom activities. This

process takes place during a “student focus session.” We have developed a guidebook for student focus

sessions, which is available on the CADRE website (http://www.colorado.edu/education/cadre). Below, we

Student focus sessions are oriented around a small number of strategically-chosen student responses to

any variation in their scores, and they come to a consensus score. They discuss ideas to modify the task and

rubric to minimize score discrepancies in the future. In phase two, participants examine the consensus scores

and the student work to generate a better sense for the strengths and weaknesses in individual students as

well as groups of students. They then discuss next steps for this student based on their analysis of the

student’s reasoning, and their goals for the student. Even though the focus is on a single student, the

students’ response is likely representative of a set of students in the class. Thus, by deeply understanding this

single student and designing responsive classroom activities, the teachers are really understanding and

designing for a group of students.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 17

Our initial analysis of student focus session suggests that they are productive spaces for improving tasks and

for understanding student reasoning. We are currently exploring two further conjectures related to student

focus sessions. First, we conjecture that student focus sessions will, over time, help teachers make principled

focus sessions as part of a LP-based SLO process improves the chance that the process will be perceived as

more than a compliance-based activity.

Note that although student focus sessions are presented here as a discrete step, they would actually continue

throughout the year, as teachers create and administer new assessment items to monitor growth.

STEP 5: MAKE CONNECTIONS FROM CULMINATING ASSESSMENT AND BODY OF

EVIDENCE TO THE LOCATION OF STUDENTS AT END OF INSTRUCTIONAL PERIOD.

SCORE STUDENT GROWTH AND REFLECT UPON THE SLO.

Using a similar process as that described in Step 3 above, teachers administer an assessment at the end of the

aggregate level can then be made by examining the distribution of growth scores and calculating summary

statistics.

improved in the following year.

• In retrospect, were some assessment items used to monitor student performance as part of student focus

sessions better than others?

• To what extent do teachers now have a bank of assessment tasks that could be used for formative purposes

in the next year?

• How could instructional activities connected to the LP be changed for the better in the next year?

• What lessons learned about students in the context of this LP might generalize to other topics for instruction?

It is important to appreciate that the most time-consuming aspect of using the LPF as a basis for SLOs is the

making gradual improvements. Finally, it is in the stage where teachers are considering the implications for

the next year where the value of an across-grade LP is especially evident because information about a

student’s LP level in the lower grade/course would become that much more relevant to the student’s parents

and the upper grade/course teacher.

CONCEPTUAL ADVANTAGES OF THE LPF

In the LP-based framework for student growth, teachers set meaningful, standards-based learning objectives

for students, create learning progressions based on those objectives, and then evaluate students, monitor

• A priority is placed on thinking about growth across multiple grades, rather than student status or level of

mastery.

• The same target is set for all students.

• Because growth can happen anywhere on the LP, teachers are not penalized for having students who enter

their class underprepared.

it means to demonstrate minimal growth.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 18

• Teacher collaboration around the discussion of student work (formalized as part of ongoing “student focus

sessions”) are central to what goes on in between the beginning and end of an instructional period.

These advantages are especially pronounced when compared to the design of the vast majority of SLO systems

threats to validity. Table 1 summarizes how the LPF may address each of these three threats.

As indicated in the above table, although we are optimistic that an LP framework may address these common

threats found in SLO systems implemented in many places, we also recognize that this approach would

pilot with a few participating schools.

IV. Limitations

Although our initial pilot work developing and implementing the LPF as a basis for SLOs suggests to us that

the approach has great potential, we do not wish to give the impression that it represents a panacea. To begin

the ground, especially if an attempt was being made to implement SLOs using an across grade LP. Developing

able to continue using the same across grade LPs developed at each school site in year 1, teachers spent a

student reasoning was evolving at various time points during the year.

common curriculum may be in place or where a common understanding of standards needs to be established

understanding of standards in place, and so we limited the LP development work this year to construct smaller

students with varying levels of sophistication know and can do in their respective content areas.

Moreover, is it unlikely that the processes supporting the LPF, which center on cultivating formative practices

to guide assessment and instructional practices, are readily scalable over a short period of time or can be

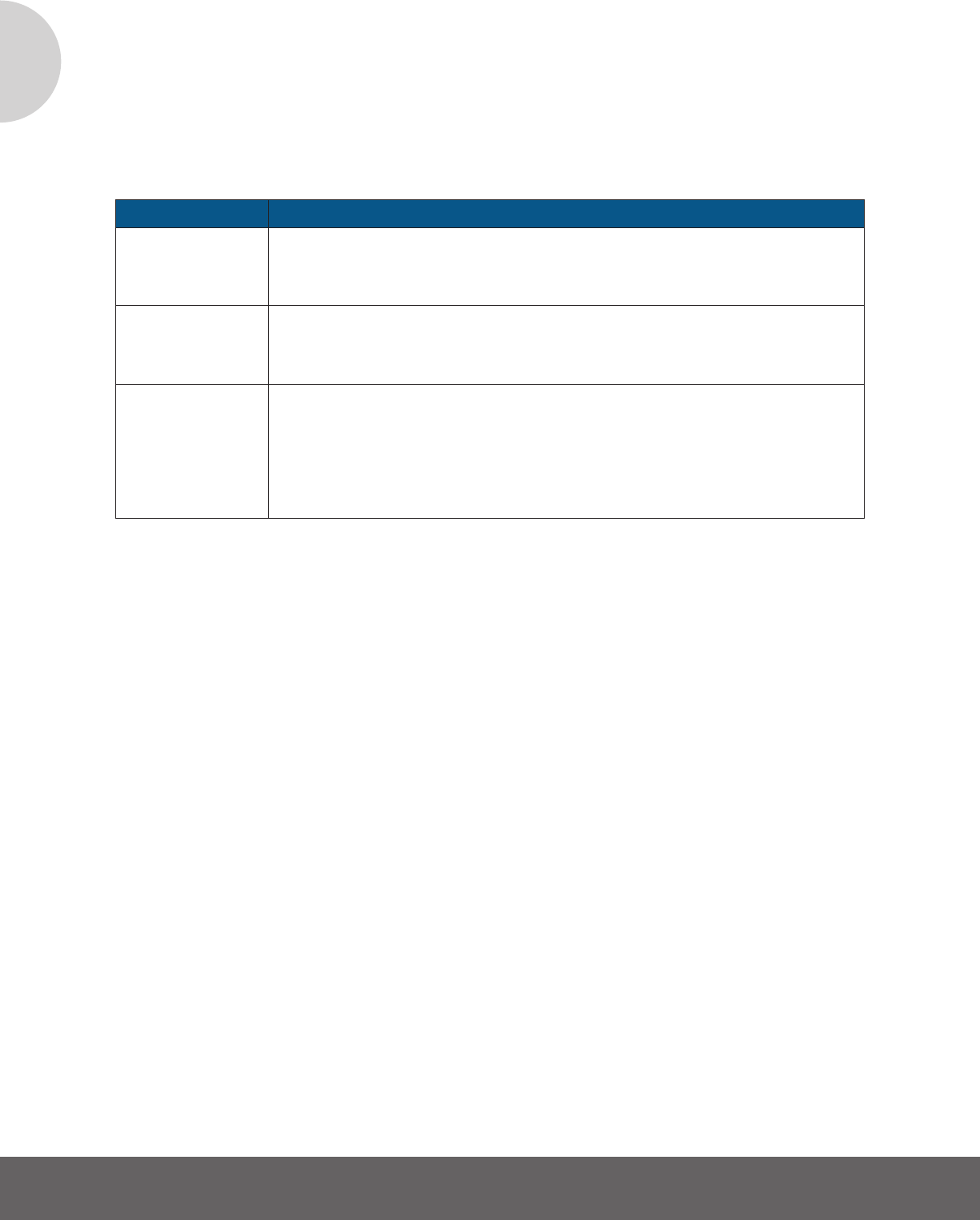

THREAT HOW AN LPF CAN ADDRESS THIS THREAT

growth

student is expected to acquire in order to reach the learning objective.

students

the LP, awarding the amount of growth achieved by each student toward reaching the learning

3. Accountability

concerns trump

instructional

improvement

Student focus sessions are central to the LP approach. This fosters teacher collaboration

around the careful study of student reasoning, and helps teachers improve assessment items,

understand student reasoning, and design learning activities based on student reasoning. By

engaging in this collaborative process with other teachers, teachers serve as peer-review

regulators for this process by checking on the quality of products used to evaluate student

learning and by evaluating the evidence presented by teachers to support claims about how

much growth was achieved by their students.

TABLE 1. SUMMARY OF THREATS ADDRESSED BY AN LP

development and collaborative time among teachers to:

• Begin the work of adapting existing LPs or in many cases with the majority of subject areas, move forward

with the work of constructing within grade or across grade LPs.

• Make adjustments to the LPs based on reviews of student work.

Most of the teachers we have worked with appreciated the opportunity to collaborate with their peers and

discuss student work relative to an LP. Further, in the case of the elective areas, participating teachers and

curriculum coordinators noted that they appreciated getting the opportunity to focus on their own content

areas and to better understand the academic expectations and instructional targets to be set for students

across grades. But within the context of this district, it is unclear whether this work could be sustained

without the extensive facilitation and supports that our research team has provided over the two-year period

at participating schools and with the group of teacher leaders and curriculum coordinators in the elective

areas. Districts that are considering this approach should be prepared to allocate substantial professional

likely to be viewed by participating teachers as an authentic and valuable process apart from its role in teacher

student growth were to shift, SLO approaches based on an LPF would have the potential to remain as an

infrastructure and process that supports good pedagogical practice and professional development. But at this

point, our conjecture is limited to our experiences working with teachers on the LP project over the past two years.

Another limitation involves psychometric concerns in using the LPF as a basis for measuring student growth.

In the general approach we have outlined, student growth is represented by transitions across discrete LP

tasks. It is quite likely that student-level growth scores would have low levels of reliability, though the

problem would be lessened when aggregated to the teacher level. In the long-term, if the approach were to be

adopted by all teachers in the same subject/grade combination in a school district, then it might be possible to

the psychometric quality of student-level growth scores would need to be given considerable scrutiny if these

were to be factored into teacher evaluations. Of course, the same issue regarding the quality of assessment

tasks used applies to the current SLOs that are being implemented. That is, SLOs based on the LPF would

surely be no worse than SLOs based on the status quo, and in many cases the LPF likely results in higher-

quality assessments. As the statistician John Tukey once wrote “Far better an approximate answer to the right

question, which is often vague, than an exact answer to the wrong question, which can always be made

Overall, the biggest limitation for implementing an LPF as the basis of the SLO process is the dedicated

commitment required for a school and district to have teachers participate in regularly scheduled student

focus sessions to review student work relative to the developed LP and to deepen their knowledge of

assessment as they engage in the process of aligning and developing high quality tasks to support inferences

However, using an LPF as the basis for SLOs would require even more time and resources due to the work

or situated within a grade. If districts or school do not schedule time for teachers to collaborate and review

week are needed to sustain student focus sessions), then the SLO approach we have sketched out in this paper

will be short-lived.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 19

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 20

summarizes the lessons we are learning from this ongoing work. This report will be released during the

process and the LP project will be used to determine how best to structure supports for the next school year

In addition, the district has begun to implement two aspects of our pilot work. First, the district is organizing

groups of teachers to begin mapping out developmental trajectories tied to their learning objectives as a way

to evaluate what novice students should know and can do relative to students exhibiting “expert”

characteristics. Second, the district is organizing teachers across content areas to begin discussing and

learning. Although the district’s work in these two areas is at a nascent stage and the student focus sessions

have not extended into evaluating the quality of tasks used by teachers, we applaud the district for moving in

the direction of integrating these types of activities into their current SLO process. Even if the use of an LPF as

an organizing framework for SLOs in the district remains a distant goal, the decision to organize collaborative

types of students know and can do will hopefully contribute to the instructional relevance of the SLO process

for teachers both in the short- and the long-term.

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 21

References

Journal of Labor Economics,25(1), 95-135.

Learning progressions

footprint conference: Final report

Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives

http://www.colorado.edu/education/cadre/publications

Retrieved from: http://www.colorado.edu/education/cadre/publications

An evaluation of the interpretability of Student Learning Objectives results in one state

based on student assessments and growth targets. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Harvard University,

manuscript. Retrieved from: http://vamboozled.com/laura-chapman-slos-continued/

Measuring the impacts of teachers I: Evaluating bias in teacher

value-added estimates

diagnostic assessments in mathematics: The challenge in adolescence. In V. F. Reyna, S. B. Chapman, M. R.

Dougherty, & J. Confrey (Eds.), The adolescent brain: Learning, reasoning, and decision making

Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

Learning trajectories in mathematics: A foundation for standards,

curriculum, assessment, and instruction.

doctoral dissertation. University of Colorado, Boulder

National Council on Teacher Quality. http://www. nctq. org/

dmsView/State_of_the_States_2013_Using_Teacher_Evaluations_NCTQ_Report.

Student learning objectives: Operations manual. Retrieved from: http://www.gadoe.org/

Identifying eective teachers using performance on the job.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Learning progressions in science

Student Achievement Measures in the Evaluation of Teachers in Non-Tested Subjects and Grades.

Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved from:

Using a Learning Progression Framework to Assess and Evaluate Student Growth 22

sustainability. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research.

Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional

Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Northeast & Islands. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/

edlabs.

Estimating teacher impacts on student achievement: An experimental

evaluation

and Learning Progressions to Support Assessment Development. Educational Testing Service: Princeton, NJ.

educators contributions to student learning in non-tested subjects and grades with a focus on student

learning objectives. Dover, NH: Center for Assessment. Retrieved from http://www.nciea.org/

Australian Council for Educational Research.

Knowing what students know: The science and design of

educational assessment. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Denver, CO.

Measures of student learning. Retrieved from:

http://www.ride.ri.gov/TeachersAdministrators/EducatorEvaluation/GuidebooksForms.aspx

Research in Education, Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY.

http://msde.state.md.us/tpe/TargetingGrowth_Using_SLO_MEE.pdf

The Annals of Mathematical Statistics