hps://proctor.gse.rutgers.edu/jusce-restoraon-educaon

By Cecelia Joyce Price

REPARATIVE JUSTICE, RACIAL RESTORATION, & EDUCATION SERIES

(Re) membering Me

In May 2019, I visited Ghana, West Africa with a group of Black women in higher educaon from across the

United States. Few of us had met before, but over those two weeks, we bonded as sisters and as women

who discovered new ways to value, embrace, and celebrate our idenes. For me, I was rst in awe of

beauful blackness everywhere, and I marveled at what it must feel like to be the majority, the default, the

norm since before one’s birth. I noted the sense of community among the Ghanaian people, the creavity

that was evident in the villages, and the beauty of the women. Most importantly, I recognized, what Cynthia

Dillard (2012) wrote about: the (re)membering of my own identy and the (re)membering of me. I returned

to the states more proud, more condent, and stronger. I am an arst - with words, and mostly, with images.

The best way I knew to express how this experience has connued to shape my life as a woman of color

in educaon was with a bit of poetry, a palate, and paint. The art that I connue to birth as a result of this

journey speaks directly to all that made a lasng impression upon me.

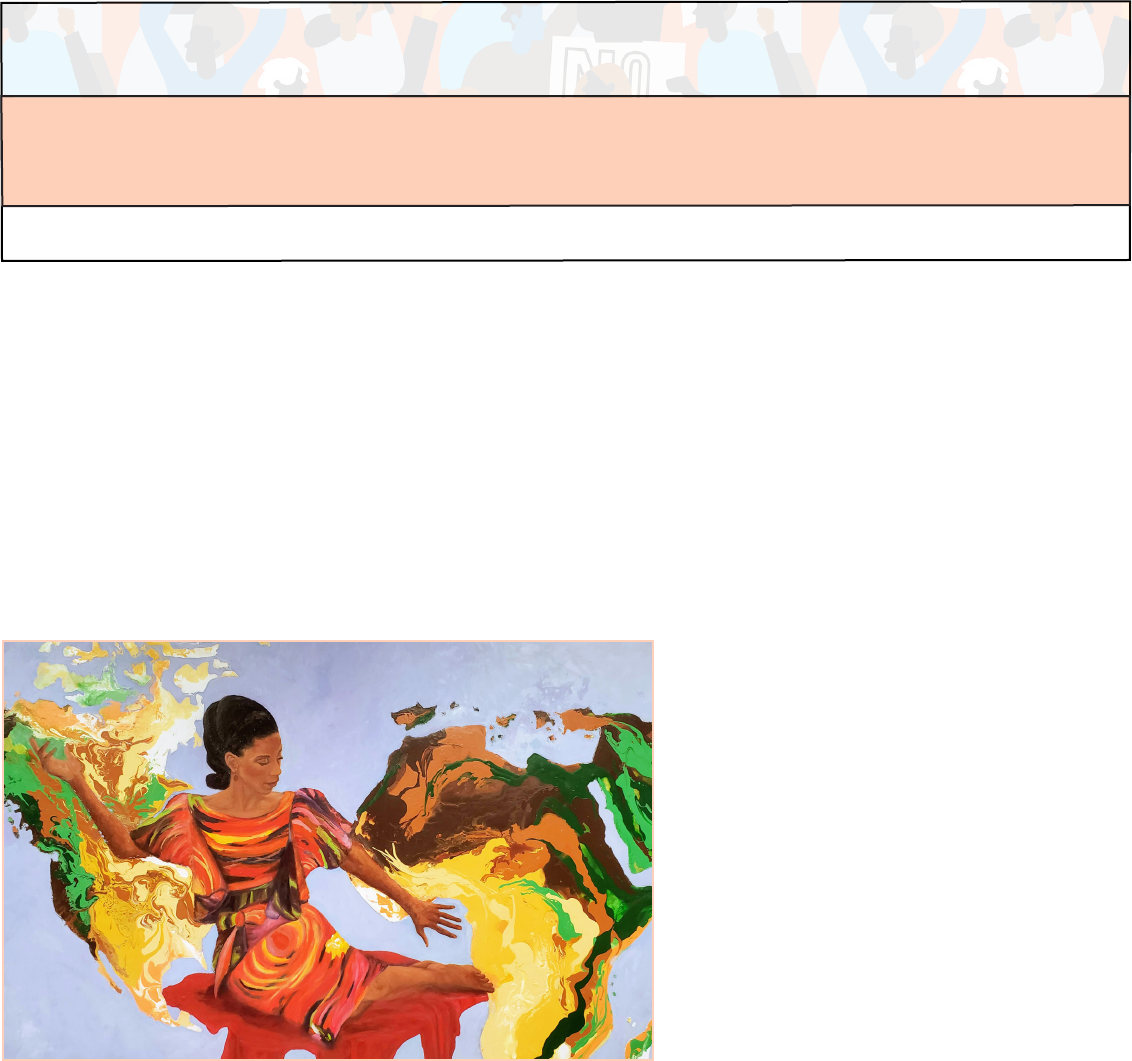

In my rst painng, a 4x6 foot piece I called

“Identy,” I honored the creavity of the

Ghanaian people which, because I am a

descendent of slaves stolen from African

shores, ows through me. I did so by

painng my own image in the dress made

of the fabric that “Aune Bea,” a Ghanaian

Village merchant, designed using a method

called “Bak.” “Aune Lucy,” another

Ghanaian entrepreneur sewed my dress

together without a paern. Both Ghanaian

women helped me (re)member my identy

as a creave. In my painng, my hand

reaches for, and my eyes peer upon, the

African shores from which my ancestors

were stolen. I am sing on a red cloth, as this is a concept piece rather than a realisc rendering. The cloth

represents the blood of my ancestors strewn across the Middle Passage, for without their blood sacrices, I

would not be. The African shores and the blood are sacred reminders which help me (re)member my gratude

and my strength. My right-hand covers, and my body leans, toward North American lands, for this is the only

home I have known. And my identy, while rooted in the majesty of the Motherland, is planted rmly there,

where all that I do with these hands takes place. That posioning between here and there helps me (re)

member the depth of my being, the character I maintain which is born of both places, and the deep respect I

have for all of the factors and pieces that make me, me.

The second, third, and fourth painngs in the series that I have named “Community + Identy = Literacy” are

tled as follows: “We Wrin’ It ALL!” (three boys wring, 18x24 inches). “Your Words on my Heart” (lile boy

looking up at his teacher, 18x24 inches), and “Lovin’ Literacy” (three lile girls reading, 20x24 inches). These

painngs follow the “Identy” piece because I wanted to illustrate how a strong sense of myself impacts

“Identy”

hps://proctor.gse.rutgers.edu/jusce-restoraon-educaon

my interacons with others. Thus, the backgrounds of these painngs are splashed with the colors of my

dress and represent how my (re)membering, the reassembling of my understanding of who I am, and the

emboldened condence that connues to rise within me as a descendent of African people has a long-

lasng, posive impact on the students in my classroom.

A h painng in the series, a 3x4 foot work,

is another representaon of what I felt while

in Ghana: a strong sense of community among

beauful Ghanaian women. While on the trip, I

took hundreds of photos of sites, but mostly of

people. Upon my return home, I studied each

image and selected an array of women and

children who represented the many walks of

life that I saw in the villages. I called this one

“Ghanaian Village Women.”

“We Wrin’ It ALL!” “Lovin’ Literacy”

“Your Words on My Heart”

“Ghanian Village Women”

hps://proctor.gse.rutgers.edu/jusce-restoraon-educaon

“Lovin’ Literacy”

I included the young, the seasoned, the babies, the teens, the grandmothers, mothers, workers, entrepreneurs,

creaves, the beauful. I selected a fabric store as the featured trading post and surrounded it with other

shops. I nished the piece by including the lovely Ghanaian shore with its peaceful sandy beaches in the

background. Currently, I am working on a sixth piece, 3x4 feet, that will feature Ghanaian village men. Peaceful

community, the central theme in these pieces, helps me (re)member my sense of responsibility to my friends,

my family, my neighbors, my students, my colleagues, the people in and around my world.

At the beginning of this essay, I menoned that upon arriving in Ghana, the rst notable awakening for me was

the blackness everywhere. At rst, it was hard to express what I meant or felt. But when I did, the outpouring

did not come in paint. It came in verse. And so, I wrote “Ebony” along with an intro called “Why ‘Ebony?’” to

set its stage:

Why “Ebony?”

When I went to Ghana, I could not, in the beginning, arculate why watching interacons among the Ghanaian

people intrigued me so. I saw Ghanaian people in the villages taking care of one another, being responsible to

and for each other. I saw people in both the villages and in the city walking here and there with condence,

looking others directly in the eyes. I sensed no anger, no threat, no fear. I saw very few police, I heard very few

sirens, and where police were present, I saw easy Interacons between them and the cizens. I saw peace.

At some point, I determined that I must be witnessing the interacons of a people who, from the beginning of

their lives, and from the beginning of their parents’ lives, and from the beginning of their grandparents’ lives,

had always been the majority – the default - the norm. Thus, they had always been in control, and they had

always governed themselves. They had not been broken.

I have experienced being part of the majority in limited spaces: at church, in my 3rd grade school, and in one

neighborhood where I used to live. I have no concept of what it feels like to be the norm from birth. My parents

don’t know that feeling, and neither did their parents or their grandparents. My friends and I are descendants

of a people who may have dominated their neighborhoods, the churches, and local stores. But the specter of

a more powerful, and somemes menacing people constantly loomed over their land, their homes, their jobs,

their neighborhoods, and somemes, over all of these.

I can only imagine that as a member of the majority, and having been such since birth, that one would not

spend much me thinking about such things. What would there be to talk about? But I, as well as most black

people, have always existed as a minority, learning as early as second grade that my appearance can incite ill-

will and that in certain sengs, I was expected to curb my speech, my topics of conversaon, and at one point,

even my appearance to accommodate the tastes and temperaments of the majority.

And so, in Ghana, I wondered for the rst me in my life: what would it have been like to exist from the

beginning only among black people? What would it have been like for this existence to remain for my enre

life? For my parents’ enre lives? For the lives of my grandparents, my great-grand parents, and my ancestors

who were taken to America? What would that have meant for my family members, for my friends, and for

students today? What if black was the default? The norm? Who would I have been? Who would my loved ones

have been? Such quesons and my experiences as a minority in the United States inspired the poem entled

“Ebony.”

Ebony

Her skin is like midnight.

Plump are her lips.

Thick are her thighs. She’s got swing in her hips.

“I’ll edit her down,” the white photographer quips.

She was more. She is more.

But what more might she be if in print of all kinds, she could say, “I see me.”

If her concepons of beauty began in Ebony?

“Walk with me,” husband says, “so they’ll treat me kindly.”

I stop, meet his eyes, and feel his sincerity.

We enter, we inquire, but the white man speaks to me.

Husband was more. He is more.

But who more might he be if he traded in markets of familiarity?

If the community faces were in Ebony?

The plans she designed outwits rival quests.

With no fear, she speaks and stuns all the guests.

But the clients dismiss as though she is less.

She was more. She is more.

But how more might she be in a network of thinkers who look like family?

If her career had begun in accomplished Ebony?

Black as default is a proud stride, a straight back, A direct look in the eye.

No concept of inner lack.

It’s moving here and there with assurance and ease,

it is owning the spaces and holding the keys.

It is no limitaons according to skin tone,

Or the sound of our speech, or the body we own.

Not that success can only be found if Blackness alone in this world did abound.

But lost between somewhere and our home of ago are assumpons of our worth

and the value we know

To be righully ours as God intended.

But taken and broken, our worth was upended.

Ghanaian-like condence and strength since suspended.

“Black as default” might ring oensive to some

Who say it disrupts the idea that “We’re one.”

But oense, I believe, is most easily embraced

By those who see in most others their face.

To ip the script, I respecully suggest

Might put that “We’re one” message to a real test...

His chubby brown hand shoots up. Without pause,

He shouts his response out loud because

He knows the answer and he just wants to please.

hps://proctor.gse.rutgers.edu/jusce-restoraon-educaon

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SAMUEL DEWITT

PROCTOR INSTITUTE

for Leadership, Equity, & Justice

But inside his lile heart drops to its knees

As he nds once again his placement outside.

Now brewing, inner rage sets in to reside.

And not yet mature, he has no words to tell

Of how school has for him, become rst-grade hell.

What more could he be?

Who more should he be?

How more would he be?

If his learning world reected his identy

And normalized,

And dignied

His Ebony?

Cecelia Joyce Price earned her doctorate in Curriculum and

Instrucon at University of North Texas, Denton. She is a

full-me faculty member in the School of Educaon at Dallas

College where she teaches, facilitates professional development

experiences, and co-sponsors a chapter of the Texas Associaon

of Future Educators.