153

PROTOTYPES

applying the lessons of tradition

chapter 5

Traditional housing holds many lessons for today’s designers and builders in the creation of humane and environmentally

appropriate environments. Following are prototypical house designs and neighborhood arrangements based on

traditional principles. The prototypes are compared to a typical “starter-home” as one might fi nd in a Southwestern

subdivision of mass-produced houses, representing today’s conventional method of production.

The prototypes have compact plan forms with the goal of building affordably and effi ciently. While a contemporary

trend in new housing development is towards building larger houses more cheaply, an alternative thesis is to build

smaller and more effi cient houses from higher-quality materials with greater energy effi ciency. To do so affordably will

require an emphasis on effi cient house design and neighborhood planning.

Each prototype is presented fi rst as an individual fl oor plan, then in a typical cluster or block plan, and fi nally expanded

to the scale of a neighborhood. The neighborhood plans are presented to illustrate the types of densities and

arrangements that are possible with the house types considered. Thought is given to the creation of common public

space for each neighborhood. This might be a park with a playground, a recreation center, or a school. In the planning

of new neighborhoods with a large enough population to support commercial development, coordination among

developers, builders and municipalities can create a plan that includes a market, café or business center in the form of

a small town plaza. These common elements serve as both literal and symbolic centers to a neighborhood.

Design of these public elements, and related concerns, such as traffi c planning, is beyond the scope of this study.

The neighborhood plans are therefore diagrammatic, serving to illustrate the principles of density, courtyards, and the

creation of private and public space. This preliminary exercise in town planning is not intended to be followed literally.

In an actual development a variety of house types should be designed that work together to create block patterns with

a built-in variety of fl oor plans and sizes. By working with common modules, a range of 2, 3 and 4 bedroom plans

can be developed

154

The prototypical housing designs which

follow include:

■ Detached single-family house plan based

on the Anglo ranch house and bungalow

traditions.

■ Attached L-shaped and U-shaped

courtyard house plans based on the

Hispanic tradition.

■ Attached 2-story row-house with terraces

based on the Native American pueblo

tradition.

The prototypes were designed with 16 inch

thick exterior walls to permit the use of any

of the three alternative materials discussed

here: adobe, rammed earth or straw bale. The

interior spaces are based on the same program

as the Base Case suburban house with regard

to the functions accommodated and the sizes

of rooms. In comparing the gross fl oor

areas of the conventional Base Case with the

prototypes, it must be remembered that the

prototypes are based on thick-walled systems,

while the Base Case has six inch thick wood

frame exterior walls. Therefore, the gross

fl oor area of the prototypes is greater than

that of the conventional house.

Effi ciency concerns not only the design of

individual houses, but more signifi cantly the

urban form or land use pattern employed

in developments. Compact house forms

with a minimum of exterior walls are both

less expensive to build and to operate. The

free-standing rectangular box, typical of

subdivisions, minimizes exterior wall area by

its centralized shape, yet it is exposed on all

sides because it doesn’t share walls with its

neighbors. If the detached housing model is

followed, large land areas are necessary along

with extensions of roads and utilities. Land

and infrastructure costs must be factored in

to the overall cost of the development.

Signifi cantly higher densities can be achieved

by joining dwelling units and sharing walls.

This reduces both the initial construction cost

and the land cost attributable to each unit, as

well as the cost of supporting infrastructure.

Savings can be dramatic for a medium to

large-scale development.

In evaluating the prototypes, interior fl oor

area is expressed as a ratio of exterior surface

area of the walls and roof. A greater ratio

result indicates a more effi cient enclosure

system. For example, the effi ciency ratio of

the detached single-family (Base Case) house

equals .46, while the effi ciency ratio of the

two-story row house (Urban Prototype 3) is

approximately four times greater, equalling 1.88.

Shared walls between attached units are

not counted in the calculation, as they are

not exposed to the elements and do not

contribute to heat loss and gain.

The alternative prototypes proposed have

two basic problems in regard to costs: (1)

they are larger than the standard minimum

tract house, and (2) they are designed of

more expensive materials. To be feasible

for affordable housing the prototypes must

be more effi cient in their overall design,

construction and land use. With additional

planning, costs can be reduced.

For traditional materials, such as adobe or

rammed earth, to be economically feasible

for use in affordable housing, walls must be

shared. These high-thermal mass materials

are twice the cost of conventional frame

walls, and so must be “built once and used

twice” that is, shared by two dwellings to

be affordable. There are further climatic

advantages to sharing walls, as this reduces

the amount of exterior wall area subject to

heat loss or gain.

As seen consistently in traditional housing,

affordability favors simplicity. The fl oor

plans resolve into rectangles and squares.

Rooms are arranged in simple volumes and

alignments, and often connect directly one to

the other without hallways. This directness

and simplicity may seem startling, but is the

result of the designers and builders using the

most direct and economical means.

Sure ways to reduce construction costs

include reducing the size of houses, and

sharing functions within a single space. A

combined living/dining/kitchen area is a

more effi cient use of space than creating

separate rooms. All of the prototypes may be

further reduced in cost by reducing the size

EFFICIENCY AFFORDABILITY

155

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

or number of rooms. For example bedrooms

may be reduced by up to 20 percent in area by

reducing them from a standard 12 ft. by 11 ft.

size to an 11 ft. by 10 ft. dimension. Houses

can function adequately with one bathroom,

rather than two as is now commonly expected.

Dividing bathroom plumbing fi xtures so that

a toilet and sink are together in one space,

and a tub/shower and a second sink are in an

separate space, allows the family the effective

use of two bathrooms, while not incurring

the cost of two full bathrooms.

To reduce the life-cycle costs of maintenance,

the use of durable materials, such as adobe

or rammed earth, is encouraged. Using

traditional passive heating, cooling and

ventilation methods as explored in this report

will reduce utility bills, as the house can stay

comfortable for more of the year without

needing to run the mechanical system. The

initial cost of building a traditionally planned

house using traditional southwestern materials

is higher than using conventional planning

and materials. Yet the home owner can

learn the value of owning a more effi ciently

designed house, built of environmentally

responsible materials, that costs less to own

and operate over its lifespan.

In considering these alternatives, the concept

of building smaller houses of higher quality

design and materials is valid with regard

to advancing the use of adobe or other

alternative construction materials in the

Southwest border region.

To maintain privacy for individual dwellings

while achieving higher density development,

use of the courtyard type of housing is very

important. Courtyard and patio homes are

also climatically and culturally appropriate for

many low-moderate income families in the

U.S. Southwest. Courtyards provide the oasis

in the desert at the heart of each dwelling,

as witnessed in the numerous traditional

examples surveyed.

The greater effi ciency of the high-density/

low-rise design approach can off-set the higher

cost of building with adobe, rammed earth or

straw bale. Although the construction cost of

an adobe courtyard house is higher than that

of a standard detached wood frame house,

the overall project cost may be equalized once

the costs of land and infrastructure are taken

into account. Courtyard housing appears

to be a feasible alternative for a number of

reasons.

Cultural and social factors:

■ Courtyard houses refl ect a centuries-

old Latin tradition.

■ The courtyard at the heart of the house is

essentially a large out-door room, a private

place for outdoor living.

■ Neighborhoods of courtyard houses

are pedestrian-friendly, a positive

social environment with greater .

opportunities for social interaction.

■ Greater population density creates

defensible space, reducing crime.

Environmental factors:

■ Courtyards have passive cooling and heating

advantages, creating an oasis/micro

climate for the summer and allowing sun

in the winter.

■ Shared walls reduce exterior surface and

reduce heat loss & gain.

■ Greater effi ciency of land use reduces

infrastructure costs, preserves wildlife.

Economic factors:

■ Higher densities possible with courtyard

planning reduce land and infrastructure

costs.

■ Shared walls between courtyard houses

can make use of adobe or rammed earth

possible.

■ Compact houses with courtyards use less

energy and cost less to own and operate than

detached suburban houses.

■ The courtyard provides the largest room

in the house: views into the courtyard

make the interior feel more spacious,

allowing smaller-sized rooms to be used.

Following are prototypical house designs

presented in order of increasing density.

Preliminary cost estimates are based on regional

per-square-foot costs for single-story houses

with nine foot ceilings, wood or metal truss

roofs, exposed concrete fl oors, and economy-

standard, fi nishes, fi xtures and hardware, as of

summer 2004.

COURTYARDS AND DENSITY

156

production quality, meeting minimum

property standards, of the sort used in

production homes. Roofs are structured with

prefabricated wood or metal trusses. Roofi ng

is corrugated galvanized iron sheeting.

The alternative designs with earthen walls

are estimated with a per-square foot cost

factor that is twelve percent higher than a

conventional frame/stucco house. This

refl ects a rule of thumb that the exterior

walls of a house account for roughly one-

fi fth of the total construction cost. Given

that earthen walls cost twice as much to build

as conventional frame/stucco walls, we have

a 100 percent increase for 20 percent of the

project, equaling a twenty percent greater cost

for the alternative method of construction.

Some of the additional cost can be recovered

through sharing walls, but clearly not all walls

can be shared. If approximately two fi fths

of the exterior walls can be shared through

courtyard design and attached units, the

twenty percent additional cost is reduced to

around twelve percent greater overall. As an

arithmetic equation, it looks like this:

Estimated cost for incorporating alternative

wall systems in housing construction:

COST ESTIMATES

The comparative cost estimates which follow,

for the Base Case and the four alternative

prototypes, are based on approximate land

and construction costs in southern Arizona,

current as of the fall of 2004. Because

costs vary with both market conditions and

geographic areas, these estimates serve only

to illustrate in relative terms the range of

probable costs incurred by varying housing

types and land uses.

Construction costs are estimated on a per-

square-foot basis, which serves to set the cost

within a range, plus or minus ten percent. For

purposes of these estimates, construction is

as illustrated in the prototypical wall sections

presented in Ch.3. Many design decisions

which affect building costs have to do with

fi nishes (such as fl oors, walls, ceilings, roofi ng

etc.). These estimates assume that fl oors

are exposed colored concrete. Straw bale

walls are plastered inside and out. Stabilized

adobe walls are left exposed (i.e. unplastered)

inside and out. Interior partitions and

ceilings are fi nished with gypsum board and

painted. Such elements as doors, windows,

and cabinets are assumed to be of moderate

The approximate cost of land per acre

is weighted to refl ect urban versus rural

locations. Urban land is estimated at $50,000.

per acre, while rural land is estimated at

$25,000. per acre. While land prices vary

widely based on location, these amounts are

averages of land prices found in the Multiple

Listing Service for Southern Arizona

counties.

These numbers are predicated on improved

land, with roads and utilities existing to

the lot lines. Rural sites may have wells for

domestic water supply and septic systems

for waste disposal, rather than connections

to a municipal water and sewer systems.

Additional costs for infrastructure including

roads, water, sewer, natural gas, and electricity

must be factored for remotely sited rural land

or undeveloped urban lots.

The economic and environmental advantages

of infi ll development on vacant urban land

is underscored by the cost savings realized in

using existing infrastructure.

“The stereotype of the conventional individual dwelling is

that of a box sitting on a lot surrounded by space. The box

has no privacy as the windows are outward looking, and the

surrounding [yard] is [also] not private.”

Peter Land,

Economic Housing: High Density, Low Rise, Expandable

for freestanding house:

100% cost increase of wall x 1/5 wall / house ratio = ( 1.0 x 0.2 ) = 20 % greater cost

for attached house:

20% greater cost x ( 100% - 40% shared walls ) = ( 0.2 x 0.6 ) = 12 % overall increase

157

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

The housing needs and expectations of a family with from two to four children in the contemporary U.S.

Southwest are refl ected in the subdivisions found in sun belt cities such as El Paso, Las Cruces, Tucson and

Yuma. The suburban model has been followed by both private non-profi t and government sponsored

housing programs, including Habitat for Humanity, USDA, HUD and FmHA rural housing programs, as well

as on Native American reservations by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and local tribal governments. It is a

widely accepted standard of what constitutes an affordable, adequate family home.

The Base Case home has a combined living/dining space adjoining a separate kitchen with a refrigerator, sink

and stove. The dining area accommodates a table for six. There are three bedrooms, one slightly larger as a

parents’ bedroom, and two bathrooms, one of which is accessed from the parent’s room. All bedrooms have

closets. There is accommodation for a single car in a carport (shaded overhead, open on the sides). Space for

clothes washing and drying machines is provided off the carport.

The typical house has a concrete slab-on-grade fl oor and wood stud walls fi nished with stucco at the exterior

and gypsum board at the interior. The wall cavities and attic are insulated with fi berglass batting. The roof is

pre-fab wood trusses with OSB sheathing and asphalt shingles. The house is mechanically heated and cooled

by a heat-pump air conditioner, which must run much of the year as the house does not incorporate passive

heating, cooling, or ventilating strategies.

The single-family detached house is placed in rows on blocks of subdivided land, each house in the middle

of its lot with windows on all sides. There is a poor relationship of indoor to outdoor space. For example, if

one wishes to dine outdoors in privacy one must bring food from the kitchen, across the carport, around the

side yard, and fi nally to the backyard.

The Base Case represents a typical single-story southwestern neighborhood where emphasis is placed on

accommodating the automobile. The resulting low-density development consumes a signifi cant amount of

land, and lacks a distinctive community form.

SUMMARY

Wall material: 2 x 6 frame/stucco

Gross Floor Area: 1,224 sf

Exterior Surface Area: 2,657 sf

Ratio of Floor Area to Surface Area: .46

Estimated cost of construction: @ $90/s.f. = $ 110,160.

Density of land use: 4.5 RAC

Cost of land per unit @

($50,000/Acre)/(4.5 RAC) = $ 11,111.

TOTAL ESTIMATED COST PER UNIT: $121,271.

157

PROGRAM

Suburban wood frame/ stucco house BASE CASE

158

0 16

scale in feet

PLAN

N

ELEVATION

BASE CASE CONVENTIONAL SUBURBAN HOUSE

EXTERIOR WALLS: 2x6 WOOD FRAME W/ STUCCO

159

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

“BASE CASE” CONVENTIONAL SUBURBAN HOUSE

16 RESIDENCES / 3.52 ACRES = DENSITY 4.5 RAC

0

100

scale in feet

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN

N

boundary of density calculation

160

“ Homes which keep or improve their quality will retain or multiply the original investment and support the tradition of

keeping houses in families from generation to generation. Thus houses become genuine and stable assets for families, in

contrast to rented apartments.”

Peter Land, Economic Garden Houses

161

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

In rural areas with abundant inexpensive land, and where the detached single-family home is the preferred

option, houses should be effi ciently planned and responsive to the environment. Illustrated here is a modest

interpretation of these goals based on the precedents of the traditional southwestern ranch house and

bungalow. This prototype is recommended for small, isolated rural replacement housing, in clusters of from

six to twelve houses.

The plan is a simple rectangle based on a 4-foot module to make the most of 4’ straw bales, 24”on-center

roof truss spacing and 4’ x 8’ roof sheathing. The plan measures 32’ x 44’ outside-to-outside. The exterior

walls are proposed of 16” thick straw bale with lime/sand plaster. The window and door jambs carry the

load of the roof, allowing the straw to serve as enclosure and insulation. A central wall running the length

of the house is proposed of 16” thick rammed earth. This provides a central thermal mass to stabilize

interior air temperatures.

The exterior straw bale walls provide high insulation value, while the central earth wall

provides high thermal mass.

Roof framing is prefab wood or metal trusses with recycled cellulose insulation,

OSB sheathing and corrugated metal roofi ng. Interior partitions are wood or metal studs with 5/8” gypsum

board. Deep roof overhangs shelter the straw bale walls, and a porch wraps the corner of the living room to

provide shaded outdoor living space.

Public and private spaces are separated by the central earth wall, with bedrooms along one side and the

living/dining/kitchen on the other. Closets are placed between bedrooms to increase acoustic privacy. The

children’s rooms are grouped together, with the parent accessed by a private alcove. The bathroom design

achieves the equivalent of two separate bathrooms with the plumbing of one bathroom. A tub/shower and

sink together in one space, while a toilet and sink are in a separate space. This allows one family member to

shower while another uses the toilet, effectively doubling the use of the bathroom at a reduced cost.

The hypothetical site is fl at irrigated cropland as found in many areas of California, Arizona, New Mexico,

and Texas along the U.S./Mexico border. The houses are grouped informally around a central loop road that

gives access off a primary county road, of the type that runs along section lines between agricultural fi elds

in the rural southwest. This removes the houses from the higher-traffi c area, and creates a common area

for kids to play and neighbors to barbecue. The open space improves privacy between houses, which are

oriented primarily east-to-west for favorable solar exposure.

SUMMARY

Wall material: straw bale exterior walls, rammed earth center wall

Gross Floor Area: 1,320 sf

Exterior Surface Area: 2,532 sf

Ratio of Floor Area to Surface Area: .52

Estimated cost of construction: @ $95/sf = $125,400.

Density of land use: 2.8 RAC

Cost of land per unit @

($25,000/Acre)/(2.8 RAC) = $ 7,100.

TOTAL ESTIMATED COST: $ 119,300.

Rectangular Detached House RURAL PROTOTYPE

FLOOR PLAN

SITE PLAN

162

0 16

scale in feet

PLAN

N

ELEVATION

RURAL DETACHED PROTOTYPE

straw bale

rammed earth

material legend

163

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

0

100

scale in feet

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN

N

164

“The patio or court-yard house is well suited to contemporary needs... Its history in vernacular and architectural forms goes back well over

2,000 years... It permits light and ventilation from the inside patio, thus eliminating the need for space or openings around the perimeter

of the dwelling and thereby permitting houses to be nested contiguously at high densities on relatively] small lots with considerable

economies in infrastructure.”

Peter Land, Economic Housing: High Density, Low Rise, Expandable

165

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

Where a closely-knit community form is desired for cultural, climatic or economic reasons, the “U” type

courtyard house provides a good model. This example is drawn from the zaguán and courtyard tradition of

the Southwestern U.S. and Northern Mexico. It can be built effi ciently in groups of four, eight, or multiples

of eight. Where multiple blocks are developed, the placement of housing blocks creates a central common

park or plaza.

The “U” plan wraps a central courtyard on three sides, with public spaces fronting the street and bedrooms on

the courtyard. Pedestrian entry is via a zaguán, that connects to the courtyard. A continuous porch connects

the opposite sides of the courtyard. A parent’s bedroom suite is across the courtyard from the children’s wing

for privacy. The bedrooms are large enough for two siblings each. Two full bathrooms are provided, as well

as a utility room/laundry off the single carport. The house shares walls with its neighbors on two sides, while

the carports also share a common partition.

Exterior walls are proposed of 16” thick stabilized adobe, left unplastered or (budget permitting) stuccoed

with lime/sand plaster of varying integral colors. The wall thickness would allow either rammed earth or

straw bale to be used as well. The roof structure is prefab wood or metal trusses with recycled cotton fi ber

insulation, OSB sheathing and corrugated metal roofi ng. Interior partitions are wood or metal studs with

5/8” gypsum board.

This prototype is superior in terms of functional arrangement and privacy. Due to the thick walls, the

additional space of the zaguán entry, and the generous utility space provided, this 3 bedroom 2 bath

prototype is larger than other options. At 1,600 s.f. it is 30 percent larger than the base case suburban model.

To be competitive this prototype must achieve 30 percent savings in reduced land and infrastructure costs. A

compact version of this house without the zaguán and with smaller rooms could be developed if necessary

to make the approach feasible.

The assumed site is a gently sloping plain near a small agricultural town in the southwest. Changes in grade

can be accommodated by stepping the fl oor elevations along the shared walls, as illustrated by the Street

Elevation. Changes in plaster color of the walls or wainscoting can be used to distinguish the joined houses

from one another. This type of housing creates pedestrian scaled urban architecture along the model of the

Rio Sonora valley towns.

SUMMARY

Wall material: adobe, rammed earth or straw bale.

Gross Floor Area: 1,600 sf

Exterior Surface Area: 1,987 sf

Ratio of Floor Area to Surface Area: .67

Estimated cost of construction: @ $100/sf = $ 160,000.

Density of land use: 7.1 RAC

Cost of land per unit @

($50,000/Acre)/(7.1 RAC) = $ 7,000.

TOTAL ESTIMATED COST: $ 167,000.

“U” Type Courtyard House URBAN PROTOTYPE 1

FLOOR PLAN

SITE PLAN

166

“U” TYPE COURTYARD HOUSE

EXTERIOR WALLS: 16” THICK ADOBE, RAMMED EARTH, OR STRAW BALE

0 16

scale in feet

FLOOR PLAN

N

167

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

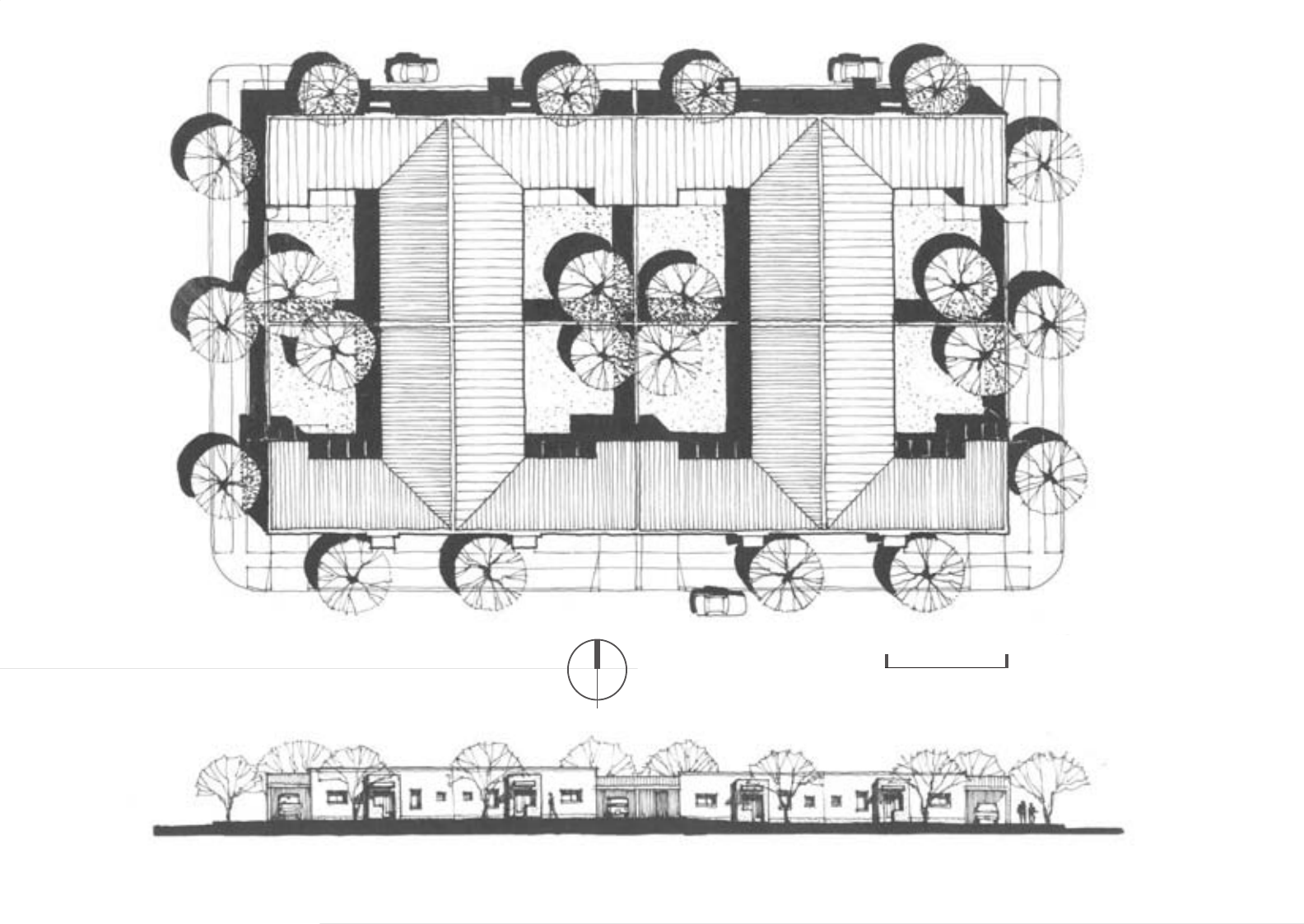

“U” TYPE COURTYARD HOUSE: 8 RESIDENCES / 1.13 ACRES = DENSITY 7.1 RAC

0 32

scale in feet

BLOCK PLAN

N

STREET ELEVATION

168

“U” TYPE COURTYARD HOUSE: 32 RESIDENCES / 5.68 ACRES = DENSITY 5.6 RAC

0 100

scale in feet

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN

N

boundary of density calculation

169

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

Based on Mexican examples in northern Sonora and southern Arizona, the “L” plan leaves a generous

private patio or courtyard on one corner, and shares walls with adjacent dwellings on two sides. The house

is brought forward to strengthen the pedestrian presence at the street, in stark contrast with the conventional

subdivision’s garage-dominated street facade. As with the “U” plan, the “L” plan locates its outdoor space

within the house in the form of a courtyard.

The public spaces, living, dining and kitchen, are located on the short leg of the “L” at the street front. The

bedrooms are placed on the long leg of the “L”, each with direct access to the courtyard. A larger parent’s

room is located at the farthest end of the patio, with its own bath and closet. Two children’s rooms connect

to both the patio and an internal hall, which is necessary only at higher elevations in cooler zones.

At or below

an elevation of 2,500 feet above sea level, the hallway may be omitted.

Deleting the hall would allow for larger

bedrooms, accommodating a second child in each. As in Mexican examples, access to the bedrooms can be

across the patio. A deep roof overhang protects the outdoor access, and shades windows and doors.

The exterior walls are proposed of adobe or rammed earth, exposed or plastered (budget permitting). As

with all proposed prototypes, roof framing is prefab metal or wood trusses with corrugated metal roofi ng.

Interior partitions, fi nishes and cabinets are economy standard. The special qualities of the house would

come from the earthen walls, stained concrete fl oors and the courtyard space. This option has a large

courtyard measuring 33’ x 38’, as compared with a 24’ x 24’ square courtyard including an 8’ wide porch

at the “U” plan. This leaves open the possibility of adding a future room along the side of the courtyard

behind the carport/laundry area. This might be a studio, a workshop or an additional bedroom/bathroom.

This built-in fl exibility is a distinct advantage of this plan type.

Following the principles of courtyard housing, the “L” plan permits high-density/low-rise development.

The Block Plan and Neighborhood Plan illustrate the degree of density that may be achieved while yet

maintaining privacy by virtue of the courtyard. The modularity of the block plan allows for subtle changes

in grade between the groupings of houses. The overall neighborhood is focused on a central plaza with open

space for recreation.

SUMMARY

Wall material: adobe, rammed earth or straw bale.

Gross Floor Area: 1,311 sf

Exterior Surface Area: 1,937 sf

Ratio of Floor Area to Surface Area: .63

Estimated cost of construction: @ $100/sf = $ 131,000.

Density of land use: 6.9 RAC

Cost of land per unit @

($50,000/Acre)/(6.9 RAC) = $ 7,000.

TOTAL ESTIMATED COST: $ 138,000

“L” Shaped Courtyard House URBAN PROTOTYPE 2

FLOOR PLAN

SITE PLAN

170

“L” TYPE COURTYARD HOUSE

EXTERIOR WALLS: 16” THICK ADOBE, RAMMED EARTH, OR STRAW BALE

0 16

scale in feet

FLOOR PLAN

N

171

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

SECTION A-A

0

8

scale in feet

172

“L” TYPE COURTYARD HOUSE: 8 RESIDENCES / 1.16 ACRES = DENSITY 6.9 RAC

0 32

scale in feet

BLOCK PLAN

N

STREET ELEVATION

173

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

0

100

scale in feet

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN

N

“L” TYPE COURTYARD HOUSE: 64 RESIDENCES / 9.7 ACRES = 6.6 DENSITY RAC

boundary of density calculation

174

“Characteristics of houses and neighborhood:

a) Individual houses to create an optimum habitat for contemporary living needs in compact groupings which maintain

independence and allow [human interpersonal] contact.

b) Houses oriented to interior patio gardens for family privacy, outside extension of living [space] and full use of all lot area.

c) Expandable houses which can increase in size from minimal units to ones of optimum area with internal fl exibility to

accommodate changing family space needs.

d) Low unit costs achieved through simplifi ed unit design, maximum use of minimum space, improved building methods and

dimensional standardization.

e) High density and compact development to (a) minimize distances and introduce walking as the main form of movement and

communication; (b) reduce the extension of infrastructure and (c) use land effi ciently.

f) Pedestrian streets as the main spatial focus in the neighborhood onto which face clusters of community facilities, such as shops,

schools, kindergartens, etc., within walking distance from all houses.

g) Carefully relating vehicles and pedestrians for safety, secure family life, and tranquil movement for walkers.

h) Landscaped overall environment of small community gardens, patios, lanes with trees and planting.”

Peter Land, Economic Housing: High Density, Low Rise, Expandable

175

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

Where the greatest effi ciencies of land use and environmental performance are sought, the two-story

prototype is most relevant. This approach is derived directly from Acoma Pueblo of New Mexico. Parallel

rows of multi-story joined dwellings are oriented towards the south. Each dwelling has terraces providing

private outdoor space for each family. Privacy between adjacent terraces is achieved by means of a stair-

stepping wall, which lends visual screening while yet allowing sunshine to reach the terrace and house

interior.

Each house is accessed through small private courtyards, one each at ground level on the south and north

sides. The east and west sides of each unit are common walls shared with adjoining houses, achieving a

high level of economic and environmental effi ciency. The ground fl oor includes the public spaces, while the

private spaces are on the second fl oor accessed by a centrally located stair and utility core. As illustrated in

both plan and cross section, second fl oor terraces/balconies at the north and south are accessible from each

of the three bedrooms. The parent’s suite is located across the central core from the children’s rooms for

privacy’s sake. The terraces provide a covered porch below at the ground fl oor. Each dwelling has a single

carport and exterior utility/mechanical room.

Walls are proposed of straw bale infi ll with reinforced concrete masonry (CMU) piers providing vertical

and lateral support. Straw bale when fi nished with lime/sand plaster on both sides is an effective acoustic

as well as thermal insulator, isolating the units one from the other. Roof and second fl oor construction is

composite wood framing. Glued-laminated beams are used where spans require. This is a spacious house

within a compact form.

Drawing from the urban form of Acoma, rows of houses are aligned facing south along the east-west axis. A

common space is located between the two rows of housing. This area might include a play ground, a meeting

and recreation room, or (community budget permitting) a swimming pool. Trees are located to shade the

exposed end walls of the east and west units. This example represents an effi cient use of both land and

building technology.

SUMMARY

Wall material: straw bale infi ll walls w/ CMU piers & glue-lam beams

Gross Floor Area: 1,408 sf

Exterior Surface Area: 748 sf

Ratio of Floor Area to Surface Area: 1.88

Estimated cost of construction: @ $95/sf = $ 133,760.

Density of land use: 11.1 RAC

Cost of land per unit @

($50,000/Acre)/(11.1 RAC) = $ 4,500.

TOTAL ESTIMATED COST: $ 138,260.

2 Story Row House URBAN PROTOTYPE 3

FLOOR PLAN

SITE PLAN

176

2-STORY ROW HOUSE (POST AND BEAM STRAW BALE INFILL)

0 16

scale in feet

1ST FLOOR

N

2ND FLOOR

177

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

0

10

scale in feet

SECTION A-A

178

0

20

scale in feet

NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN

N

2- STORY HOUSE: 16 RESIDENCES / 1.44 ACRES = DENSITY 11.1 RAC

boundary of density calculation

179

sw regional housing PROTOTYPES

We hope this study of regional building traditions will support alternative design and construction methods

in the production of affordable housing in the U.S. Southwest. Nonprofi t developers, builders, planners and

architects are invited to build upon the work begun here. Using traditional materials and design concepts in

new housing can both reduce energy use within the home and result in healthier communities. Nonprofi t

developers are encouraged to look beyond the fi rst cost of building houses to consider life-cycle costs, while

creating more humane and culturally sensitive environments for southwestern families.

Traditional housing and community planning ideas can still be relevant to new developments, even where the

higher cost of materials, such as adobe or rammed earth, prohibit their use. For example, our study suggests

that rammed earth is feasible for affordable housing only if it is largely subsidized by volunteer labor. Where this

is not possible, and where conventional materials must be used, the ranch house, the bungalow, the courtyard

and the zaguán still have much to tell us regarding the design of individual houses and neighborhoods.

Thus, even if traditional materials cannot be used for fi nancial or practical reasons, the affordable housing

community is encouraged to apply the valid ideas embodied in traditional housing models.

FINAL REMARKS

180

SOUTHWEST HOUSING TRADITIONS

design, materials, performance