1

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

SUBSTANCE USE

AND RECOVERY

SERVICES PLAN

DECEMBER 2022-2023

Developed by the Substance Use

and Recovery Services Advisory

Committee in collaboration with

2

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................................. 5

Health equity in tribal and rural areas ................................................................................................................ 6

Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................... 7

Subcommittees ..................................................................................................................................................... 8

Contextual setting ................................................................................................................................................. 9

Committee recommendations overview ......................................................................................................... 10

Data ................................................................................................................................................................... 10

Diversion, outreach, and engagement ....................................................................................................... 10

Treatment ......................................................................................................................................................... 10

Recovery support services ............................................................................................................................. 10

Recommendation regarding the appropriate criminal legal system response, if any, to possession

of controlled substances. .............................................................................................................................. 11

Data ....................................................................................................................................................................... 14

SURSA Committee recommendations ........................................................................................................ 15

Recommendation 6: Behavioral Health Administrative Service Organization (BH-ASO) and

Recovery Navigator Program (RNP) data reporting .................................................................................. 15

Recommendation 13: Law Enforcement (LE) and Behavioral Health (BH) data collection ................ 16

Evaluation Recommendations for the Blake-bill Interventions ............................................................... 18

Diversion, outreach, and engagement ............................................................................................................ 20

SURSA Committee recommendations ........................................................................................................ 20

Recommendation 10: Expanding investment in programs along the 0-1 intercept on the sequential

intercept model .............................................................................................................................................. 20

Recommendation 12: Stigma-reducing outreach and education regarding youth and schools ..... 22

Recommendation 5: Amend RCW 69.50.4121 – Drug paraphernalia law ........................................... 23

Treatment ............................................................................................................................................................. 25

SURSA Committee recommendations ........................................................................................................ 25

Recommendation 7: Health engagement hubs for people who use drugs ......................................... 25

Recommendation 14: Safe supply workgroup .......................................................................................... 27

Recommendation 11: SUD engagement and measurement process................................................... 27

Recommendation 15: Expanding funding for OTPs to include partnerships with rural areas .......... 29

Recovery support services ................................................................................................................................. 31

SURSA Committee recommendations ........................................................................................................ 32

Recommendation 1: Legislative policy for tax incentives and housing vouchers for respite spaces 32

Recommendation 3: LGBQTIA+ community housing .............................................................................. 33

Recommendation 4: Training of foster, kinship and family or origin, parents with children who use

substances ....................................................................................................................................................... 34

Recommendation 16: Addressing zoning issues regarding behavioral health services .................... 35

3

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Recommendation 2: Legal advocacy for those affected by SUD ........................................................... 36

Recommendation 8: Employment and education pathways .................................................................. 37

Recommendation 18: Continuum of housing ........................................................................................... 38

Recommendation 9: Expansion of the Washington Recovery Helpline and asset mapping............. 39

ESB 5476 program updates .............................................................................................................................. 41

Recovery navigator program ........................................................................................................................ 41

Peer-Run and clubhouse services expansion ............................................................................................ 42

Homeless outreach stabilization transition (HOST) expansion ............................................................... 42

Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) in jail .................................................................................. 43

Contingency management ........................................................................................................................... 44

Short-term housing vouchers ....................................................................................................................... 44

Substance use disorder (SUD) family navigators ....................................................................................... 44

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................... 45

Next steps ........................................................................................................................................................ 45

Constraints and limitations ............................................................................................................................ 45

Unmet bill requirements .................................................................................................................................... 46

Appendices .......................................................................................................................................................... 47

Appendix A – Timeline ................................................................................................................................... 47

Appendix B – Recommendation 1: Legislative policy for tax incentives and housing vouchers for

respite spaces .................................................................................................................................................. 48

Appendix C – Recommendation 2: Legal advocacy for those affected by SUD .................................. 51

Appendix D – Recommendation 3: LGBQTIA+ community housing .................................................... 54

Appendix E – Recommendation 4: Training of foster and kinship parents with children who use

substances ....................................................................................................................................................... 56

Appendix F – Recommendation 5: Amend RCW 69.50, 4121 – Drug paraphernalia law .................. 58

Appendix G – Recommendation 6: BH-ASO and RNP data reporting .................................................. 63

Appendix H – Recommendation 7: Health Hubs ...................................................................................... 76

Appendix I – Recommendation 8: Employment and education pathways ........................................... 80

Appendix J – Recommendation 9: Expansion of WHRL and Asset Mapping ...................................... 82

Appendix K – Recommendation 10: Expanding investment in programs along the 0-1 intercept on

the sequential intercept model .................................................................................................................... 85

Appendix L – Recommendation 11: SUD engagement and measurement process .......................... 89

Appendix M – Recommendation 12: Stigma-reducing outreach and education, more importantly

regarding youth and schools ........................................................................................................................ 95

Appendix N – Recommendation 13: Law Enforcement and Behavioral Health data collection ....... 98

Appendix O – Recommendation 14: Safe supply workgroup .............................................................. 106

Appendix P – Recommendation 15: Expanding funding for OTPs to include partnerships with rural

areas ................................................................................................................................................................ 114

4

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Appendix Q – Recommendation 16: Addressing zoning issues regarding behavioral health services

......................................................................................................................................................................... 125

Appendix R – Recommendation 18: Continuum of Housing ................................................................ 129

Appendix S - Resources to inform a recommendation for the state’s criminal-legal response to

possession of controlled substances ......................................................................................................... 135

Appendix T – RDA evaluation recommendation ..................................................................................... 145

Appendix U – Current state programs ...................................................................................................... 153

5

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Acknowledgements

The Washington State Health Care Authority would like to acknowledge and give our deepest

gratitude to those who have and who are currently serving on the Substance Use and

Recovery Services Advisory (SURSA) Committee. Through their guidance and subject matter

expertise during the planning and development of the Substance Use and Recovery Services

Plan, HCA has been able to submit this robust and forwardthinking plan to help

Washingtonians affected by drug use and substance use disorders (SUD). Their enthusiasm,

eagerness for collaboration, grace, and time has been invaluable to the proces of this plan

development.

Table 1: Current SURSA Committee roster

Michael Langer

Director’s appointment

Lauren Davis

House of Representatives

Democrat

Dan Griffey

House of Representatives

Republican

Manka Dhingra

Senate

Democrat

John Braun

Senate

Republican

Amber Leaders

Governor’s Office

Caleb Banta-Green

Addictions, Drug & Alcohol

Institute at UW

Julian Saucier

Adult in recovery from SUD who

experienced criminal legal

consequences

Amber Daniel

Peer recovery services provider

Brandie Flood

Anti-racism member

Stormy Howell

Representative of a federally

recognized Tribe

Chad Enright

Prosecutors Office

John Hayden

Public defender

Kevin Ballard

Local government

Sarah Melfi-Klein

Association of Washington Health

Plans

Sherri Candelario

Recovery housing provider

James Tillett

Outreach services provider

Christine Lynch

SUD treatment provider

Sarah Gillard

Representative of experts

serving people with co-

occurring SUD and mental

health conditions

Donnell Tanksley

Washington Association of

Sheriffs and Police Chiefs

Malika Lamont

Representative of experts on the

diversion from the criminal legal

system to community-based care

for people with SUD

Chenell Wolfe

Adult in recovery from SUD

who experienced criminal

legal consequences

Alexie Orr

Adult in recovery from SUD who

experienced criminal legal

consequences

Hunter McKim

Youth in recovery from SUD with

criminal legal consequences

Kendall Simmonds

Youth in recovery from SUD

with criminal legal

consequences

Addy Adwell

SUD provider Union member

6

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Health equity in tribal and rural areas

When considering services across the state of Washington, special attention is

given to select areas, including those in rural counties, that have less access to

amenities and services than those in urban areas. The current system that makes the

distinction between these two types of counties is built on the decennial censuses and

may not be comparable due to methodological changes and absence of bridging data

among census decades. There is also notice taken into the differences in health status

indicators between rural and urban residents that might reflect underlying differences

in the economic and socio-demographic characteristics in these regions. When the

recommendations of these plans are considered and developed, distinction and

consideration is given to meet the needs of these areas.

The Committee further dedicates itself to adhere to the principles of health

equity and justice for American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) communities, people of

color, and other affected populations. The Committee provides representation from

various populations, while working in collaboration with AI/AN, people of color, and

other populations that have been oppressed by dominant culture. The Committee has

examined strategies and activities to understand how current work can be used to

address inequities in substance use disorder, treatment, and recovery services. Voices

in subcommittees provided an avenue to understand cultural barriers to treatment and

recovery and examine what we can do in the future to provide meaningful, culturally

appropriate services.

We recognize that input from tribes and tribal organizations (AI/AN), people of

color, and other affected populations is essential to help guide our initiative developed

out of the Engrossed Senate Bill 5476, in a way that respects the culture and traditions

of individual communities and impacts of systemic racism.

7

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Executive summary

In 2016, an individual was arrested. Upon jail booking, a corrections officer found a small

amount of methamphetamine in their clothing. They were subsequently charged and

convicted of Unlawful Possession of Controlled Substance under RCW 69.50.4013. The

individual appealed the ruling and argued that they did not know there was

methamphetamine in the jeans, which were gifted from a friend two days prior.

On February 25, 2021, the Washington State Supreme Court vacated the conviction and ruled

the Controlled Substance Statute unconstitutional, stating RCW 69.50.4013 violates the due

process clause as it does not protect individuals who unknowingly were in possession of a

substance.

This ruling, and the resulting decriminalization of controlled substance possession, led to the

passing of Engrossed Senate Bill 5476 and the creation of the Substance Use Recovery

Services Advisory (SURSA) Committee and eventual substance use recovery services plan.

This plan was developed on behalf of the Washington State Health Care Authority (HCA) and

made by the Substance Use Recovery Services Advisory (SURSA) Committee, as outlined in

Engrossed Senate Bill 5476 (2021): Responding to the State v. Blake decision by addressing

justice system responses and behavioral health engagement, treatment, and recovery

services.

“The authority, in collaboration with the substance use recovery services advisory

committee established in subsection (2) of this section, shall establish a substance

use recovery services plan. The purpose of the plan is to implement measures to

assist persons with substance use disorder in accessing outreach, treatment, and

recovery support services that are low barrier, person centered, informed by

people with lived experience, and culturally and linguistically appropriate. The plan

must articulate the manner in which continual, rapid, and widespread access to a

comprehensive continuum of care will be provided to all persons with substance

use disorder.”

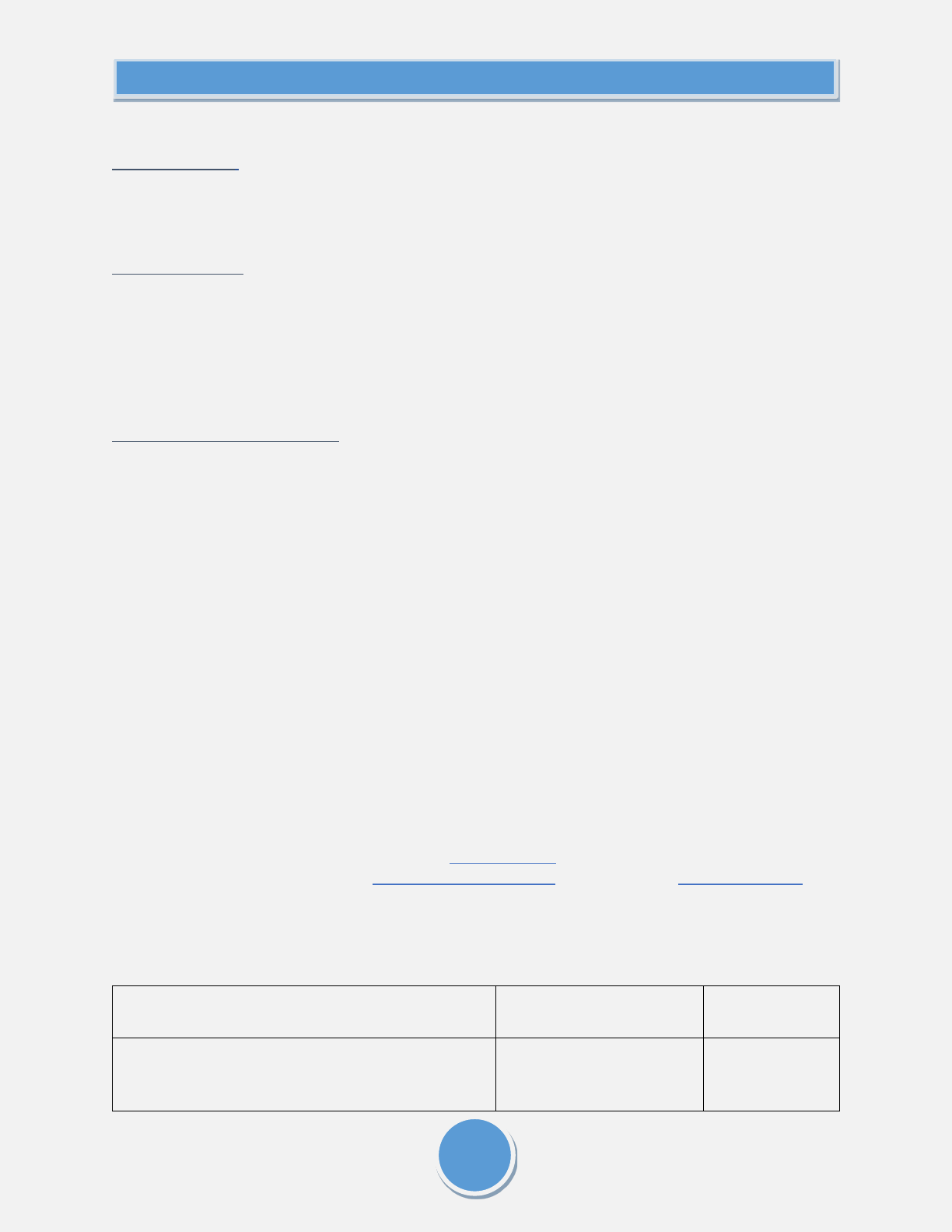

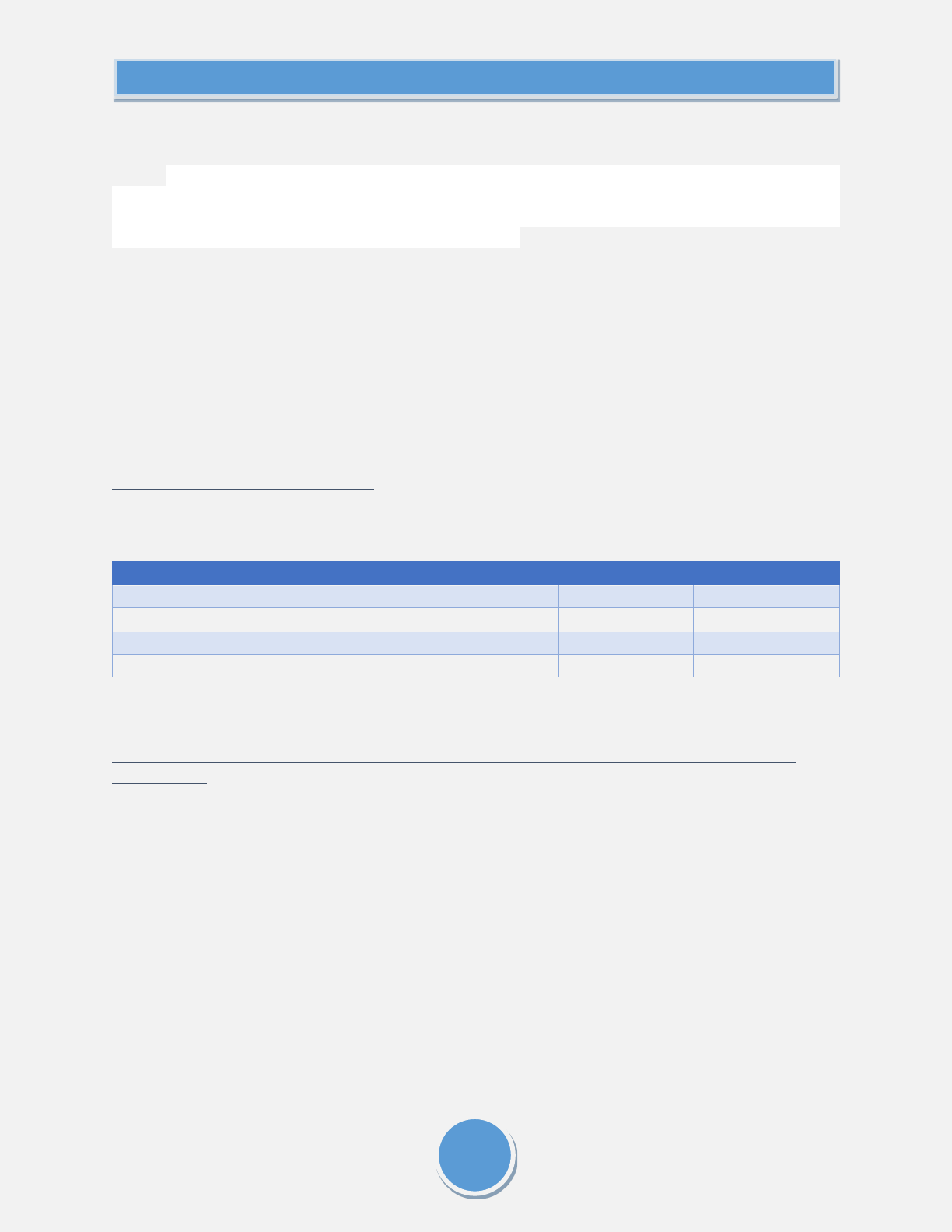

Table 2: ESB 5476 deliverable timeline

Deliverable

Date

Preliminary report to HCA

November 24, 2021

Final plan submitted to Governor and Legislature

December 1, 2022

Annual Plan Implementation Report to Governor and

Legislature

December 1, 2023, and each

subsequent year until 2026

Adopt rules/contract necessary to implement the plan

December 1, 2023

8

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Subcommittees

The SURSA Committee (Committee)

acknowledged in March 2022 that there was

a need for more Committee time and more

expertise to advise the recommendations

requested for the Substance Use Recovery

Services Plan (Plan); see Appendix A. HCA

wants to acknowledge subcommittee

participation, involvement, commitment, and

expertise provided to inform the

recommendations put forth for the Plan.

Participation in the subcommittee included:

Voices of Community Activists and

Leaders – Washington (VOCAL-WA),

along with the community members who

VOCAL-WA brought to the table to share

their lived and living experience.

Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion

(LEAD) National Support Bureau and

technical assistance team

Washington State Association of Sheriffs

and Police Chief (WASPC)

Members of Washington Alliance for

Quality Recovery Residences (WAQRR)

Washington State Association of Drug

Court Professionals (WSADCP)

University of Washington, including

Addictions, Drug & Alcohol Institute

(ADAI) and supporting staff.

Behavioral health administrative service

organizations (BH-ASOs)

Recovery Navigator Program (RNP)

administrators.

Department of Health employees

Department of Commerce employees

Washington residents with lived and

living experience

Employees of the Department of Social

and Health Services (DSHS)

Employees of the Department of

Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF)

Employees of HCA

Community-based organizations

Washington Low Income Housing Alliance

Figure 1: Timeline outline

9

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Contextual setting

Below are various terms and definitions used in the realm of substance use, that will

provide contextual background to gain a greater understanding of the work described

in the plan. The SURSA Committee and subcommittees provided feedback and

guidance surrounding these definitions.

Harm reduction: Harm reduction is a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at

reducing negative consequences associated with drug use. Harm reduction is also a

movement for social justice built on a belief in, and respect for, the rights of people

who use drugs.

1

Harm reduction involves safer use of supplies as well as care settings,

staffing, and interactions that are person-centered, supportive, and welcoming.

2

Recovery: Recovery is a process of change through which individuals improve their

health and wellness, live self-directed lives, and strive to reach their full potential.

Recovery support services (RSS): A collection of resources that sustain long-term

recovery from substance use disorder, including for people with co-occurring

substance use disorders and mental health conditions, recovery housing, permanent

supportive housing, employment and education pathways, peer supports and

recovery coaching, family education, technological recovery supports, transportation

and childcare assistance, and social connectedness.

Recovery residences: Recovery housing benefits individuals in recovery by reinforcing

a substance-free lifestyle and providing direct connections to other peers in recovery,

mutual support groups and recovery support services. Substance-free does not

prohibit prescribed medications taken as directed by a licensed prescriber, such as

pharmacotherapies specifically approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

for treatment of opioid use disorder and/or for the treatment of co-occurring disorder.

Low threshold-low barrier treatment: Increasing access to behavioral health-related

services and programs by creating person-centered programs that are easy to access,

offer a high quality of care, and eliminate barriers associated with accessing or

remaining in behavioral health treatment and related services. Elements include:

• Short time to the start of necessary medication (same day for most)

• Polysubstance use allowed initially and ongoing

• Counseling always offered, not mandated

• Urine drug screens are used to inform clinical care

3

1

https://harmreduction.org/about-us/principles-of-harm-reduction/

2

This term as normally presented excludes practice-based evidence developed and promulgated by indigenous communities

for generations. The Western model considers evidence in a narrower context that indigenous communities.

3

https://www.learnabouttreatment.org/for-professionals/low-barrier-buprenorphine/

10

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Committee recommendations overview

Recommendations are numbered according to the order in which they were voted on by the

Committee. Recommendation #17 – an amendment to the Good Samaritan Law – is not included, as it

did not receive SURSAC support.

Data

Table 3: Data recommendations

Recommendation

Type

Recommendation 6: BH-ASO and RNP data reporting

Policy/Funding

Recommendation 13: LE and BH data collection and reporting Policy/Funding

Diversion, outreach, and engagement

Table 4: Diversion, outreach, and engagement recommendations

Recommendation

Type

Recommendation 10: Expanding investment in programs along the 0-1

intercept on the sequential intercept model

Funding

Recommendation 12: Stigma-reducing outreach and education, more

importantly regarding youth and schools

Policy/Funding

Recommendation 5: Amend RCW 69.50.4121 – Drug paraphernalia law

Policy

Treatment

Table 5: Treatment recommendations

Recommendation

Type

Recommendation 7: Health Engagement Hubs for People Who Use Drugs

Funding

Recommendation 14: Safe supply workgroup

Funding

Recommendation 11: SUD engagement and measurement process

Policy/Funding

Recommendation 15: Expanding funding for OTPs to include partnerships

with rural areas

Funding

Recovery support services

Table 6: Recovery support services recommendations

Recommendation

Type

Recommendation 1: Tax incentives for landlords and respite space

housing vouchers

Policy/Funding

Recommendation 3: LGBTQIA+ community housing

Policy/Funding

Recommendation 4: Training of foster and kinship parents of children

who use substances

Policy/Funding

11

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Recommendation 16: Addressing zoning issues regarding behavioral

health services

Policy/Funding

Recommendation 2: Legal advocacy for those affected by SUD

Policy/Funding

Recommendation 8: Employment and education pathways

Funding

Recommendation 18: Continuum of housing

Funding

Recommendation 9: Expansion of WRHL and asset mapping Funding

Recommendation regarding the appropriate criminal legal system response, if any,

to possession of controlled substances

.

One of the more visible requirements of the SURS plan was the Committee’s

development and consideration of recommendations for an appropriate criminal legal

response to possession of a controlled substance. What follows is the outline and

strategies behind the development and eventual consensus surrounding a

recommendation for this legislative request.

RCW 71.24.546§1 - The authority, in collaboration with the substance use recovery

services advisory committee, established in subsection (2) of this section, shall

establish a substance use recovery services plan. The purpose of the plan is to

implement measures to assist persons with substance use disorder in accessing

outreach, treatment, and recovery support services that are low barrier, person

centered, informed by people with lived experience, and culturally and linguistically

appropriate. The plan must articulate the manner in which continual, rapid, and

widespread access to a comprehensive continuum of care will be provided to all

persons with substance use disorder.

The plan must consider: (RCW 71.24.546§3§l) Recommendations regarding the

appropriate criminal legal system response, if any, to possession of controlled

substances.

Preliminary discussions surrounding this recommendation from the SURSA Committee

produced considerations for various types of data that would assist in a meaningful

recommendation. Data sets were identified as:

Analysis of the racial impact of decriminalization of possession versus

legalization of supply through review of national and international models

Current state of the criminal legal system and how it is either being used to

incarcerate or used as leverage for individuals to enter treatment, and

successfully complete treatment

o What are the effects, and intent versus outcomes

Outcomes data for drug court participants, including analysis of racial

outcomes

Study of systemwide impacts on the community

12

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Research data on the efficacy of behavioral health interventions embedded

within the criminal legal system

Analysis of gaps in current system to take care of the individual diverted due to

decriminalization, into health care, child protective services (CPS), foster care,

etc.

o Looking at gaps where services are not available, like in rural areas

Health care cost savings for individuals who are diverted to harm reduction and

low-barrier services

Inclusivity (nature of the crime, race) of individuals in diversion programs and

their outcomes

Summary of which areas in the state are offering diversion programs for youth

Considerations of social determinants of health and the criminal legal system

Data on Involuntary Treatment Act (ITA), crisis stabilization centers and inpatient

treatment programs are working outside of the criminal system

Data comparison from what was or was not working prior to State v. Blake and

the current statute

A comprehensive resource document was created and distributed to the SURSA

Committee for their review. The document detailed the various areas where data had

been made available, based on those data requirements outlined by the Committee.

See Appendix S.

On August 8,

2022, the SURSA Committee met during a regularly scheduled monthly

meeting and participated in a straw poll exercise to assign a hierarchy of preference

regarding proposed recommendations. Table 7 summarizes the concepts discussed

and voted on as the more comprehensive components and direction for the

recommendation.

13

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Table 7: Preliminary votes on initial concepts and ideas regarding possession

The Committee requested additional time and resources to assist in advising the Committee

on implications related to the various components that may go into this recommendation. A

special Committee meeting was held on September 9, 2022, that consisted of various

presentations from:

• American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) summary of Policy Strategies from Commit to

Change Washington and the Pathways to Recovery Act

• LEAD Technical Assistance Team on pre-arrest diversion strategies from LEAD, RNP,

and Arrest and Jail Alternatives (AJA)

• University of Washington on safe supply models

• Oregon Health Justice Alliance on decriminalization successes and lessons learned

regarding Oregon Measure 110

• VOCAL- WA on disparity and inequity in criminal legal response to possession.

Through these presentations, common elements were identified to be incorporated with any

recommendation made by the Committee.

•Safe supply initiative

14

Votes

•Maintain possession of a controlled substance as a

misdemeanor with diversion options

12

Votes

•Decriminalize possession of controlled substances and

paraphernalia with no civil penalty or fines

9

Votes

•Decriminalize possession of controlled substances and

paraphernalia and make it a civil penalty

8

Votes

•Legalize possession of all controlled substances/create

a regulated market

8

Votes

•Maintain possession of a controlled substance as a

gross misdemeanor with diversion options

4

Votes

•Make possession of a controlled substance a felony,

with diversion eligibility

2

Votes

•Maintain possession of a controlled substance as a

misdemeanor, punishable only by fine

1

Vote

•Make possession of a controlled substance a felony

1

Votes

14

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Table 8: Common elements for recommendation of possession

Common elements that are required for any response to possession

Safe supply

Law enforcement

assisted diversion

and referral

options

Investments in

the behavioral

health workforce

and infrastructure

for outreach,

treatment, and

recovery services

Investment in

harm reduction

and low barrier

engagement

services

The gravity of this recommendation was taken very seriously by Committee members. While

data and additional meeting time was provided, some Committee members voiced concern

that there were some missed opportunities for a deeper understanding of the options

developed and discussed by the Committee.

The Committee made a final decision on this recommendation:

Decriminalize possession of

controlled substances and paraphernalia with no civil penalty or fines.

Data

Data requirements were identified early on as integral to a significant portion of the

outlined plan requirements, in addition to discussions about addressing the criminal

legal response to possession but also. This data subcommittee was tasked with

considering the Health Care Authority ProviderOne and Behavioral Health Data

System (BHDS) data collection systems as well as informing new data collection

parameters for the various programs within ESB 5476, such as Recovery Navigator

Program (RNP). The subcommittee addressed current concerns regarding data

collection while it developed recommendations that met the various requirements

outlined in RCW 71.24.546§3. These recommendations meet statutory requirements

found in (§1.3.h) and (§1.3.m):

(1)“ (3) The plan must consider:

(h) The design of recovery navigator programs in section 2 of this act, including

reporting requirements by behavioral health administrative services organizations

to monitor the effectiveness of the programs and recommendations for program

improvement;

(m) Recommendations regarding the collection and reporting of data that identifies

the number of persons law enforcement officers and prosecutors engage related to

drug possession and disparities across geographic areas, race, ethnicity, gender,

age, sexual orientation, and income. The recommendations shall include, but not

be limited to, the number and rate of persons who are diverted from charges to

15

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

recovery navigator services or other services, who receive services and what type of

services, who are charged with simple possession, and who are taken into custody;”

Below are the recommendations and outlined plans of action developed from this

subcommittee and approved by the SURSA Committee.

SURSA Committee recommendations

The Committee recommends establishing specific data collection and reporting

requirements among behavioral health administrative services organizations (BH-

ASOs) related to their regional recovery navigator programs (RNPs). This

recommendation also requests to identify data to be included in the RNP quarterly

reports for SURSAC review to monitor program effectiveness and inform

recommendations for improvements. The recommendation addresses ESB 5476

Section 1.3(h), related to “reporting requirements by behavioral health administrative

service organizations to monitor the effectiveness of the programs and

recommendations for program improvement.”

As a key aspect of the Plan

and the state’s response to

the State v. Blake supreme

court ruling, the Recovery

Navigator Program was

initiated as soon as possible

following the passing of ESB

5476. Uniform Program

Standards were established,

and HCA developed a draft

data collection workbook for

use by the BH-ASOs and

RNP contractors. The BH-

ASOs have contracted with

local providers and community-based organizations, and those providers have hired

staff who are collecting those data which are being tracked in the data collection

workbook.

This recommendation requests to:

Seek funds to implement a data integration platform that can serve both

as a common database for diversion efforts across the state and as a data

Recommendation 6: Behavioral Health Administrative Service Organization (BH-

ASO) and Recovery Navigator Program (RNP) data reporting

16

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

collection and management tool for practitioners. If possible, leverage

existing platforms already in use by HCA-funded efforts and any closed

loop referral systems implemented in the future.

Establish a quality assurance process for BH-ASOs to ensure that data in

the data collection workbooks are clean, complete, and accurate before

submitting to HCA, and a plan in place for data that is deemed unverified

for submission

Where applicable, add data validation to data fields in the data collection

workbook (e.g., only dates accepted under DOB and date of referral,

only 7-digit numbers accepted in ProviderOne ID, etc.)

It is expected that individuals served by RNP will be engaged in long-term, intensive

case management. While some “light touch” participants could see significant

individual benefits in a relatively short period of time, many individuals will have

complex co-occurring challenges, including extensive criminal-legal system contact.

For these participants, progress toward health, wellness, and stability is expected to

take much longer than a year, so evaluations of the RNP in its early years should

include determining measures and measures of change (in knowledge, attitudes, or

actions) for systems stakeholders, not only data that can assess participant-level

formative and outcome metrics.

While the impacts of a systems-change initiative like RNP are unlikely to be seen within

the first few years, Washington State should currently work to establish the necessary

capacities and processes to enable both formative evaluation and summative

evaluation of effectiveness. This will likely require the integration of a new data

infrastructure or processes that can exploit existing and new streams of data

pertaining to an individual’s criminal legal system encounters/involvement, and the

outreach, treatment, and recovery support services they receive through RNPs.

See Appendix G.

The recommendation requests building upon, and providing ongoing funding for, a

data integration infrastructure that can receive and analyze standardized data

gathered by law enforcement, courts, and prosecutors; Recovery Navigator Program

case management; behavioral health treatment services; and recovery support

services, to meet the mandates of Section 1.3(m) “regarding the collection and

reporting of data which identify the number of persons law enforcement officers and

prosecutors engage related to drug possession and disparities across geographic

Recommendation 13: Law Enforcement (LE) and Behavioral Health (BH) data

ll i

17

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

areas, race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, and income. The

recommendations shall include, but are not limited to, the number and rate of persons

who are diverted from charges to recovery navigator services or other services, who

receive services and what type of services, who are charged with simple possession,

and who are taken into custody.”

The focus in this recommendation is on a general data infrastructure for reporting key

indicators. Data is being collected in various sectors and programs related to

substance use and behavioral health systems (law enforcement encounters, treatment,

recovery support services programs, Recovery Navigator Program, etc.)

Many of those data systems do not have a consistent identifier across systems, or

consistent standards for data collection and classification, which creates redundancies

and makes it difficult to link the data between sectors. This hinders understanding of

the patterns taking place among different communities and their outcomes following

an encounter with law enforcement. Consistent data gathering and integration

methodologies such as those described in this recommendation would meet the data

mandates of 1.3(m). A data integration infrastructure such as the one described in this

recommendation has been implemented in four Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion

(LEAD) pilot sites per RCW 71.24.589 (Whatcom, Snohomish, Mason, and Thurston

counties) and three Arrest and Jail Alternatives grantee sites per RCW 36.238A.450

(Olympia, Port Angeles, Walla Walla).

In addition to the legislative mandated collection of data addressed above, the

following data suggestions to be collected and reported are:

System utilization

• Use of emergency medical services

• Arrest, days in jail

• New charges with incident date after of referral to RNP (divided by

felony, misdemeanor), to be added to Case Management tab in RNP

Data Collection tool

• Convictions with incident date after date of referral to RNP (broken into

felony / misdemeanor), to be added to Case Management tab in RNP

Data Collection tool

• Access to and engagement with culturally appropriate, non-punitive,

community-based resources

System response

• Capacity and variety of local services aligned with RNP’s commitment to

harm reduction and holistic care

18

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

• Number and percent of substance possession-related law enforcement

encounters (e.g., public order) that result in arrest, booking, and/or

convictions for RNP-eligible behaviors, as well as the demographics of

those individuals engaged by law enforcement in these encounters

• Racial disparity analysis that compares demographics of individuals who

are arrested and booked into jail, compared to the demographics of

those who are referred to RNP, among diversion-eligible individuals

Quality of life

• Self-report quality life/well-being

• Improved mental and physical health

Services and access gap analysis: indicated by comparing services

needed/requested by RNP participants, referrals made, referred services

received by BH-ASO region, and reasons why services were not received (if

applicable). If the data collection burden for case managers is too great for this

level of analysis, request that case managers report areas where service gaps

are a persistent problem.

RNP participant satisfaction: collected via survey every six months following

enrollment in RNP, with procedures in place outlining minimum and maximum

contact efforts.

See Appendix N.

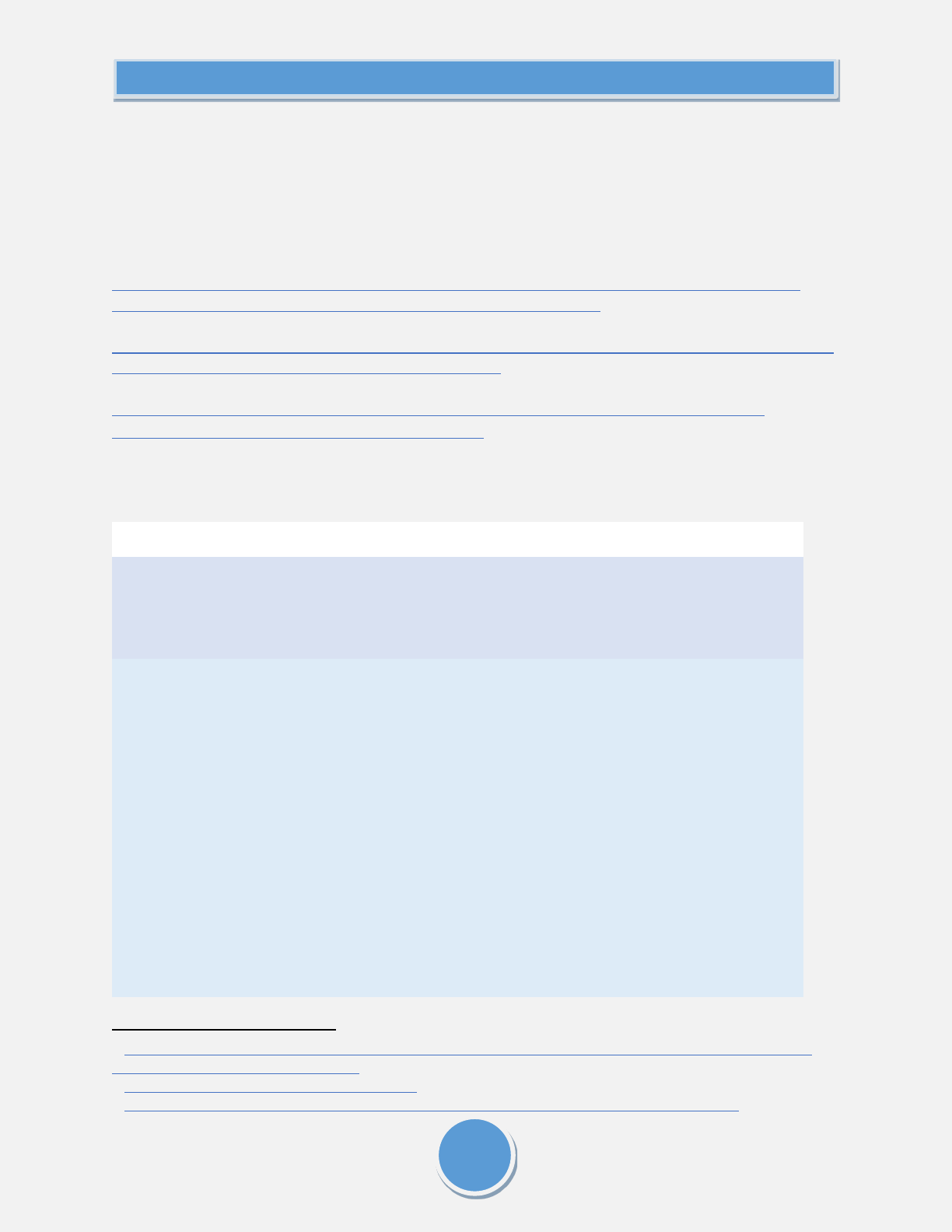

Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) Research and Data Analysis Division

(RDA), provided an evaluation recommendation for programs developed from the

Blake bill decision. The programs included in this evaluation recommendation include

Recovery Navigator Program (RNP), Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) in

Jails, Peer-Run and Clubhouse Services Expansion, Homeless Outreach Stabilization

Transition (HOST) Expansion, and Substance Use Disorder Family Navigators.

The RDA-recommended evaluation strategy focuses on efficiently estimating the

impact of each Blake intervention on the above outcomes to inform decision makers

about their overall and relative effectiveness. RDA recommends a general analysis of

outcomes broadly applicable to all Blake interventions; program-specific

strategies/outcomes may be further developed with input from the evaluator, RDA,

program staff, and other individuals designated by HCA.

Evaluation Recommendations for the Blake-bill Interventions

19

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

To efficiently estimate the effectiveness of the Blake interventions, RDA recommends a

strategy that employs similar methods across the programs and focuses on a common

set of relevant outcomes. The quasi-experimental evaluation will compare the

outcomes of service recipients “enrolled” in each intervention (treatment group) with

the experiences of statistically similar individuals who were not enrolled in the

intervention (comparison group) and then draw inferences about the effectiveness of a

specific intervention.

The specific construction of each outcome measure (e.g., number of arrests per year,

arrest rates, felony arrests, months of SUD treatment, etc.) will be determined in

collaboration with the evaluator, RDA, program staff, and other individuals designated

by HCA. Baseline descriptions of program participants and propensity score matching

will be possible as soon as a sufficient number of clients are enrolled in any given

program.

4

Typically analyses of this type employ 12- to 18-month pre- and post- periods to

characterize outcomes. The time periods to be used in these analyses will depend on

reporting deadlines, implementation schedules, and lags in the availability of data for

specific outcome measures.

HCA program managers should work closely with service providers and RDA to ensure

this information is routinely and systematically collected and maintained in a medium

that supports the efficient transmission of data. Some programs collect information on

disparate spread sheets; others, such as the RNP, utilize sophisticated case

management software. Future opportunities for analyses on the relative effectiveness

4

The “sufficient” number of participants will depend on the expected effect size of any given intervention. Interventions

expecting large effect sizes require small samples.

Treatment Groups

Comparison Groups

Outcome Measures

at Baseline

Outcome Measures

at Baseline

Post-period Outcome

Measures

Post-period Outcome

Measures

Blake

Intervention

Within group differences in outcomes

Between group

differences in

outcomes

Pre-Intervention

(Baseline) Measures

• Demographics

• Criminal History and incarcerations

• Substance use disorders

• Mental health diagnoses

• Chronic Medical Conditions

• Employment

• Housing status

• Etc…

Post-Intervention Outcomes

• Re-arrests and jail days

• ED utilization and hospitalizations

• Behavioral health treatment

• Access to primary care

• Housing services

• Employment

20

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

of different intervention service components may be possible for programs that collect

sufficient additional information on their clients.

See Appendix T.

Diversion, outreach, and engagement

Diversion services were one of the most crucial components of addressing ESB 5476

and the Blake decision. The legislation led to the creation of the Recovery Navigator

Program, providing regional resources to law enforcement diverted individuals to help

access care. This subcommittee was tasked with developing ideas on diversion along

with the subsequent engagement and outreach components of the plan. These

recommendations meet statutory requirements found in: (§1.3.a) and (§1.3.g).

(1)“ (3) The plan must consider:

(a) The points of intersection that persons with substance use disorder have

with the health care, behavioral health, criminal, civil legal, and child welfare

systems as well as the various locations in which persons with untreated

substance use disorder congregate, including homeless encampments,

motels, and casinos;

(g) Framework and design assistance for jurisdictions to assist in compliance

with the requirements of RCW 10.31.110 for diversion of individuals with

complex or co-occurring behavioral health conditions to community-based

care whenever possible and appropriate, and identifying resource gaps that

impede jurisdictions in fully realizing the potential impact of this approach;”

Below are the recommendations and outlined plans of action developed by this

subcommittee and approved by the SURSA Committee.

SURSA Committee recommendations

The SURSA Committee recommends continued and increased investments in

evidence-based diversion programs that operate along intercepts 0 and 1 on the

sequential intercept model

5

, including, the Recovery Navigator Program, Arrest/Jail

Alternative programs, LEAD, and other harm reduction, trauma-informed, and public

health-based approaches. These programs and interventions center around a racial

justice lens for providing support to underserved communities and populations.

5

For More information on the Sequential Intercept Model: https://www.prainc.com/sim/

Recommendation 10: Expanding investment in programs along the 0-1 intercept

on

the sequential intercept model

21

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Amending RCW 10.31.110 (Alternatives to Arrest – Individuals with mental disorders

or substance use disorders) and RCW 10.31.115 (Drug Possession – Referral to

assessment and services) would reflect how these programs should be used as part of

a statewide arrest and jail diversion system by mandating availability of services within

a supportive network of care.

Consistent with the Plan requirement outlined in RCW 71.24.546§3(i), this

recommendation requests shifting funding from the punishment sector to increase

and sustain investments to ensure equitable distribution of, and access to, culturally

appropriate, non-punitive, community-based resources, including treatment.

“(g)Framework and design assistance for jurisdictions to assist in compliance with the

requirements of RCW 10.31.110 for diversion of individuals with complex or co-

occurring behavioral health conditions to community-based care whenever possible

and appropriate, and identifying resource gaps that impede jurisdictions in fully

realizing the potential impact of this approach.”

To provide services, outlined below, to the Washington youth population, the request

was made to provide adequate policy changes to address systemic barriers, and

Centers for Medicaid Services (CMS) State Plan Amendment, for services made

available to youth starting at the age of 13, the minimum Medicaid enrollee age

without an adult, and incorporate Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD)

accessibility and coverage.

A range of services are noted as diversion options, those services are:

• Crisis stabilization units for youth and adults

• Triage facilities for youth and adults

• Designated 24/7 crisis responders

• Mobile crisis response services for youth and adults

• Regional entities responsible for receiving referrals

In addition, these services should be made available in all regions as well:

• ASAM-alternative SUD Assessments for youth and adults

• Syringe service programs for youth and adults

• Health Hubs for youth and adults who use drugs

• Detox/withdrawal management for youth and adults

• MOUD for youth and adults

• Outpatient treatment for youth and adults

• Ensure that long-term harm reduction-supported case management is available

after diversion so that diversion becomes meaningful

See Appendix K.

22

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Providing education related to

naloxone administration and

overdose identification in

Washington State public

schools (grade 6 – 12) helps to

reduce stigma and save lives.

Outlined in §1.3.a, this

recommendation would

provide substantial

preventative and life-saving

recognition and training in the

administration of naloxone for

students, administrators,

teachers, and other

educational professionals, at points of intersection for those that may be affected, or

know someone who is affected, by SUD.

In 2019-2020, youth under 24 years saw the highest increase in mortality, 59 percent,

compared to other age groups. With the dramatic increase in substance use mortality,

it is imperative to reduce the discrimination and judgment leveled against youth and

young adults who use drugs. This may be achieved through practical strategies

including, but not limited to naloxone distribution within school settings, overdose

education, evidenced-based drug safety curriculum starting at the sixth grade, and

partnerships with other community organizations that advance the health and well-

being of young people. Safety First is an example of learning curricula for young

people that is evidenced based and/or promising practice. The SURSA Committee

noted additional policy and statutory amendments were necessary to help support

efforts to expand services to youth and eliminate the stigma directed at people who

use illicit substances.

RCW 69.50.412: Prohibited acts: E—Penalties. (wa.gov) prohibits the distribution of

hypodermic syringes to people under the age of 18. This RCW prohibits entities

and/or individuals from distributing intramuscular syringes needed for naloxone

administration. Intramuscular naloxone is currently substantially cheaper than nasal

formulations – being limited by cost and access of naloxone due to RCWs may

exacerbate any disparities of substance use mortality among persons under the age of

18. This law will need a technical amendment to remove barriers to life saving

medication.

Recommendation 12: Stigma-reducing outreach and education regarding youth and

schools

23

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Stocking a “standing order”

(as defined in RCW

69.41.095) of “opioid

overdose reversal

medication” (e.g., Naloxone)

is required via RCW

28a.210.390 to be stocked in

high schools (grades 9-12)

already for school districts

with more than 2,000

students. These medications

can be administered by a

school nurse, a health care

professional, or trained staff

person located at a health

care clinic on public school

property under contract with

the school district or

designed trained school

personnel. Funding would

need to be provided to

increase naloxone and

overdose education among

school aged young people

(grades 6 – 12), which includes funds related to outreach and communication.

See Appendix M.

The SURSA Committee recommends amending RCW 69.50.4121 to remove language

that prohibits “giving” or “permitting to give” drug paraphernalia in any form, so that

programs that serve people who use drugs do not risk class I civil infraction charges

for providing life-saving supplies needed for comprehensive drug checking, safer

smoking equipment, and other harm-reduction supplies to engage and support

people who use drugs. The Committee recommends the state expressively preempt

the field in Washington State regarding any penalties imposed for selling/giving

paraphernalia per RCW 69.50.4121. Applying this amendment will support low-

barrier, person-centered outreach and treatment services that improve safety for

Recommendation 5: Amend RCW 69.50.4121 – Drug paraphernalia law

Figure 2: 2022 King County medical examiner data

24

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

people who use drugs, considering the points of intersection that people with

substance use disorder have with behavioral health systems and the places where

people with untreated substance use disorder congregate (Section 1.3(a)).

Many SUD service programs, especially harm reduction programs, are experiencing

significant barriers adapting to accommodate changing drug use patterns and

unprecedented surge of deaths from overdose, and to engage equitably with all

people who use drugs and in all manners of ways that people are using drugs. Much

of this is in due to paraphernalia laws that prohibit the distribution of drug

paraphernalia in any form. Amending this RCW would allow harm reduction programs

to provide drug testing equipment, including but not limited to fentanyl test strips,

and safer smoking equipment to engage and support people who use drugs without

risk of incurring a class I civil infraction.

See Appendix F.

25

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Treatment

The treatment subcommittee was developed out of the need for addressing

components of the plan directly related to treatment services and Medicaid, along

with private insurance. The treatment subcommittee focused on reviewing current

state processes and improving available engagement and treatment options to adapt

to the increased need. The subcommittee consisted of researchers, behavioral health

treatment providers, and subject matter experts to inform the recommendations

below. The subcommittee was able to address ideas and develop recommendations

that met various requirements outlined in Section 3. These recommendations meet

the following statutory requirements in RCW 71.24.546: (§3.a), (§3.b), (§3.c),(§3.d),

and (§3.e).

(1)“ (3) The plan must consider:

(a) The points of intersection that persons with substance use disorder have with the

health care, behavioral health, criminal, civil legal, and child welfare systems as well

as the various locations in which persons with untreated substance use disorder

congregate, including homeless encampments, motels, and casinos;

(b) New community-based care access points, including crisis stabilization services

and the safe station model in partnership with fire departments;

(c) Current regional capacity for substance use disorder assessments, including

capacity for persons with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental health

conditions, each of the American society of addiction medicine levels of care, and

recovery support services;

(d) Barriers to accessing the existing behavioral health system and recovery support

services for persons with untreated substance use disorder, especially indigent

youth and adult populations, persons with co-occurring substance use disorders

and mental health conditions, and populations chronically exposed to criminal legal

system responses, and possible innovations that could improve the quality and

accessibility of care for those populations;

(e) Evidence-based, research-based, and promising treatment and recovery

services appropriate for target populations, including persons with co-occurring

substance use disorders and mental health conditions;”

Below are the recommendations and outlined plans of action developed from the

treatment subcommittee and approved by the SURSA Committee.

SURSA Committee recommendations

Recommendation 7: Health engagement hubs for people who use drugs

26

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Health Engagement Hubs serve as an all-in-one location where people who use drugs

can access a range of medical, harm reduction, treatment, and social services.

Developing Health Engagement Hubs for people who use drugs considers and

supports several plan elements, including points of intersection that persons with

substance use disorder have with the health care system (RCW 71.24.546§3.a),

locations in which persons with untreated substance use disorder congregate (ibid),

new community-based care access points (RCW 71.24.546§3.b), and barriers to

accessing the existing behavioral health system (RCW 71.24.546§3.d). This

recommendation draws most immediately from a State Opioid and Overdose

Response Plan (SOORP) Goal 2.2.1 and expands upon work from the Center for

Community-Engaged Drug Education, Epidemiology and Research (CEDEER) at the

UW Addictions, Drug, & Alcohol Institute, including low barrier buprenorphine

programs and expressed needs/interests from program participants at Syringe

Services Programs (SSP).

The subcommittee proposes Health Engagement Hubs to be affiliated with an existing

SSP serving each community as well as other entities as appropriate, including

federally qualified health centers (FQHCs)/community health centers (CHCs), patient

centered medical homes, overdose prevention/safe consumption sites, peer run

organizations (e.g., Club Houses), services for unhoused people, supportive housing,

and opioid treatment programs. Harm reduction services and supplies must be an

integral program component of any organization housing a health hub.

Services should address each of the care domains below, with as comprehensive a

service mix as feasible:

• Comprehensive physical and behavioral health care

• Medical case management services/care coordination

• Harm reduction services and supplies

• Community health outreach workers/navigators, peers

• Linkage to housing, transportation, and other support services

• Spiritual Connection Communities

Health Engagement Hubs should encourage community volunteers, and provide

appropriate training to staff and volunteers, including diversity, equity, and inclusion

training. Services should be offered in coordination with every willing SSP.

Communities with a SSP may also offer services in other settings described above.

Communities without a SSP may provide services in another setting given they

institute a comprehensive harm reduction service and staffing continuum.

See Appendix H.

27

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

As part of the discussion surrounding the criminal legal response to possession of a

controlled substance, the SURSA Committee identified safe supply as a necessary

component to address diversion by providing safe resources for people who can

benefit from this type of harm reduction service. The treatment subcommittee

recommends assembling a statewide workgroup to make recommendations on a

framework for safe supply for future inclusion in the Washington State Substance Use

Recovery Services Plan. The workgroup would detail how the state may provide a

regulated, tested supply of controlled substances to individuals at risk of drug

overdoses. The workgroup should center the voices of people who use drugs, with

lived and living experience, and who have lost loved ones. This workgroup should

consider values of non-commercialization and alternative lawful income source for

people who have been trapped in the illicit distribution economy and could be

displaced by a safe supply program, to prevent potential unintended consequences

that would disadvantage communities most impacted.

The recommendation meets individuals at points of intersection that persons with

substance use disorder have with the health care system and locations in which

persons with untreated substance use disorder congregate (RCW 71.24.546§3.a). It

also addresses barriers to accessing the existing behavioral health system and

recovery support services for persons who use drugs and/or with untreated substance

use disorder, and possible innovations that could improve the quality and accessibility

of care for those populations (RCW 71.24.546§3.d) by using evidence-based,

research-based, and promising treatment and recovery services appropriate for

priority populations, including persons with co-occurring substance use disorders and

mental health conditions (RCW 71.24.546§3.e).

See Appendix O.

The recommendation that follows covers the component of the plan focused on low-

barrier, person-centered care which should be informed by people with lived and

living experience. This recommendation asks that:

o HCA convene a workgroup that will review current processes and

workforce needs related to intake, screening, and assessment for

substance use disorder (SUD) services

o HCA determine how to build an SUD engagement and measurement

process, including developing any necessary rules and payment

mechanisms

Recommendation 14: Safe supply workgroup

Recommendation 11: SUD engagement and measurement process

28

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

o HCA work with people who use drugs (PWUD), care providers, state

regulators, and payors to address this recommendation within 12

months

o In the interim, any work that HCA can undertake to advance these goals

should be done

Because SUD is chronic and potentially acutely life-threatening:

Initial engagement should be person centered and address the needs expressed by

the person seeking services. Current evaluations focus on complete and lengthy

assessments designed to determine the severity of a person’s substance use disorder

and the type of treatment setting best designed to meet their needs. Recognizing not

everyone will be ready for or interested in traditional treatment at the time of

engagement, Initial assessments should center on understanding and meeting the

persons self-identified needs, for example, food, shelter, harm reduction supplies,

recovery supports information or same day treatment if available, in the order that best

suits them. This approach also helps to build trust.

Access to timely SUD assessments varies widely across Washington State. In urban

areas, people seeking or needing an assessment may go to drop-in hours multiple

times over several weeks before they obtain an assessment. In rural areas there may

be a single provider currently allowed to do assessments and they may have a multi-

week wait list. Alternatively, in some care settings all that is needed to initiate care is an

SUD diagnosis (e.g., a medical clinic with a licensed prescribing provider onsite). The

Care for people with SUD needs to be accessible and initiated as quickly as

possible.

Care for people with SUD needs to be accessible in places and care settings

that are low-barrier/crisis-oriented (e.g., Health Hubs for people who use drugs

(PWUD), emergency departments, CHC/FQHC) in addition to care settings

such as withdrawal management and specialty SUD treatment.

The initial engagement and measurement process should be focused on what

is minimally necessary to document a diagnose, determine medical necessity

and start care the same day, and be conducted in less than 15 minutes.

Initial engagement and SUD measurement must be focused on, and limited to,

client’s needs and should be limited to only the necessary domains. Trauma

and culturally informed approaches must be taken in terms of the total time,

content, and process of engagement and measurement.

29

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

variable access to care by geography, provider types, and care settings is an example

of state and federal rules and regulations negatively impacting equitable access to

care.

See Appendix L.

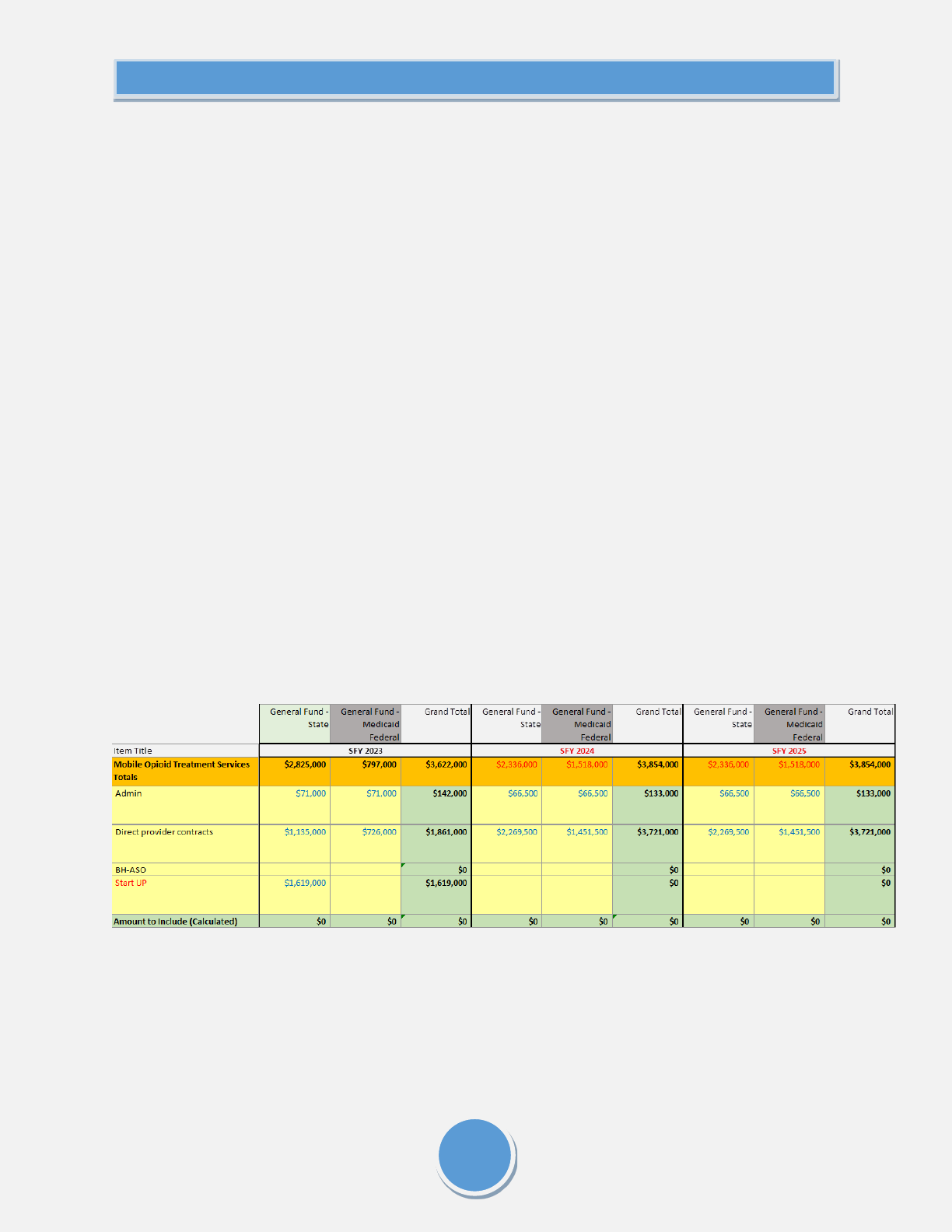

The recommendation proposes expanding funding for opioid treatment programs

(OTP), to include mobile OTPs, into rural areas. As of September 1, 2022, there are 32

OTPs in Washington State, each serving between 200 to more than 1,000 patients.

There is no federal rule limiting the number of individuals an OTP can serve, but state

law in RCW 71.24.590(2) does allow counties to set patient census limits (i.e.,

maximum capacity for a program). OTPs in Washington State collectively serve more

than 14,000 people with a primary OUD diagnosis.

This recommendation establishes new community-based care access points (RCW

71.24.546§3.b), expands regional capacity for treatment via opioid treatment

programs (RCW 71.24.546§3.c), and removes geographic barriers to accessing OTPs

(RCW 71.24.546§3.d). Additionally, this recommendation aligns with the State Opioid

and Overdose Response Plan (SOORP) Strategy 2, establishing access to the full

continuum of care for person with opioid use disorder and Strategy 3, support and

increase capacity of opioid treatment programs.

Access to opioid treatment program (OTP) services in rural areas recommendation

includes:

Encourage the Department of Health’s Health Services Quality Assurance

(HSQA) division to create a regulatory workshop with OTP provider

stakeholders in 2023 to:

o Create state rules/regulatory process for OTP that want to establish

offsite medication units (1) located as a free-standing facility; (2) co-

located within in a variety of community settings such as but not limited

to hospitals/medical primary care systems/pharmacies/FQHCs, as well as

correctional health settings, etc.

Change RCW 36.70A.200 and WAC 365-196-550 to ensure that OTP branch

sites of all kinds (including mobile, and fixed, site medication units) are clearly

seen as “essential public facilities” and that they cannot be zoned out or stalled

by moratoriums by city and/or county legislative authorities.

Recommendation 15:

Expanding funding for OTPs to include partnerships with rural

30

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Update RCW 71.24.590 to remove several requirements for the siting of opioid

treatment programs that stigmatize the treatment setting type and subject

these treatment centers to a higher burden of regulations than other behavioral

health treatment settings.

Funding for capital construction costs to help start up OTP in Central and

Eastern Washington.

Funding to a state agency such as HCA for established OTPs in Washington

State to operate an increased number of OTP medication units in order to

expand their geographic reach.

See Appendix P.

31

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

Recovery support services

As one of the first subcommittees generated from the SURSA Committee, the recovery

support services subcommittee was tasked with further developing recommendations

which populated out of the preliminary SURSA Committee meetings. The

subcommittee was able to address these initial ideas and develop more

recommendations that met the various requirements outlined in Section 3 of RCW

71.24.546. The recommendations below meet statutory requirements: (§3.a), (§3.b),

(§3.c),(§3.d), and (§3.e).

(1)“ (3) The plan must consider:

(a) The points of intersection that persons with substance use disorder have

with the health care, behavioral health, criminal, civil legal, and child welfare

systems as well as the various locations in which persons with untreated

substance use disorder congregate, including homeless encampments,

motels, and casinos;

(b) New community-based care access points, including crisis stabilization

services and the safe station model in partnership with fire departments;

(c) Current regional capacity for substance use disorder assessments,

including capacity for persons with co-occurring substance use disorders and

mental health conditions, each of the American society of addiction medicine

levels of care, and recovery support services;

(d) Barriers to accessing the existing behavioral health system and recovery

support services for persons with untreated substance use disorder, especially

indigent youth and adult populations, persons with co-occurring substance

use disorders and mental health conditions, and populations chronically

exposed to criminal legal system responses, and possible innovations that

could improve the quality and accessibility of care for those populations;

(e) Evidence-based, research-based, and promising treatment and recovery

services appropriate for target populations, including persons with co-

occurring substance use disorders and mental health conditions;”

Below are the recommendations and outlined plans of action developed from this

subcommittee and approved by the SURSA Committee.

32

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

SURSA Committee recommendations

This recommendation stemmed from the

need to continue recovery residential

operations that offer MOUD services

along with providing more housing

options in all areas of Washington. The

recommendation attempts to provide a

strategy to mitigate the current housing

market. The 2022 housing market consists

of homeowners and recovery residences

operators/owners finding it to be more

profitable to sell their homes rather than

continue to operate. The cost of real estate is working against the community and

supportive system for those who are seeking recovery services. Operators are shifting

out of recovery housing and selling their homes to capitalize on the current market.

The recommendation also addresses an approach for providing respite spaces for

individuals who return to use or are awaiting treatment services. Housing operators

would provide these spaces or create new residences to meet these individual’s

needs.

The recommendation outlines strategies to mitigate current markets while creating

new community care access point (§3.c), at points of intersect for individuals with SUD

(§3.a), using evidence-based, research-based, and promising treatment and recovery

services appropriate for target populations (§3.e).

The subcommittee proposes:

A property tax break for landlords to incentivize leasing their rental homes to

housing operators.

o Amending RCW 84.36.043: Nonprofit organization property used in

providing emergency or transitional housing to low-income homeless

persons or victims of domestic violence. (wa.gov), to include recovery

residences under the exemption that currently only provides

opportunities to transitional homes that house people for two years

or less.

A new voucher program would be ideal for experienced and accredited

housing operators to hold bedspace for individuals who are awaiting

appropriate treatment or who have returned to use and need a place to stay

while negotiating a return to stable housing.

Recommendation 1: Legislative policy for tax incentives and housing vouchers for

it

33

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

ESB 5476 established housing grants provided by the Department of Commence in

conjunction with the Health Care Authority. To receive this funding, housing providers

must meet national standards and accreditation of the Washington Alliance for Quality

Recovery Residences (WAQRR). Tribes are currently establishing relationships with

WAQRR to further expand housing options. The grant funding provided previously

should continue and give priority to tribes and rural areas for these grants.

See Appendix B.

The Health Care Authority and Department of Commerce should be intentional when

it comes to housing equity and inclusivity, and to the safety of LGBTQIA+ community

members. This recommendation addresses current disparities regarding this

population while drawing from intersections of people with substance use disorder

(§3.a), addresses barriers to accessing the existing behavioral health system and

recovery support services (§3.d), creates new community care access points (§3.c) by

using evidence-based, research-based, and promising treatment and recovery

services appropriate for target populations, including persons with co-occurring

substance use disorders and mental health conditions (§3.e). Currently, housing

providers have several individuals who apply and are accepted into housing that

identify with the LGBTQIA+ community, but there are no supportive policies or

training for operators to care for this population in a profound way.

Housing policy should be inclusive of LGBTQIA+ through state funded training for

housing providers and drug courts on how to service this community in an informed

and appropriate manner.

Harassment training

Communication

Antiracism training

Gender affirming/diversity training

Cultural competency training

A low-barrier grant program where funding is contingent on implementing

inclusionary policies operated through the Department of Commerce geared at

recovery-based housing in underserved and rural areas for priority populations. To

provide appropriate staffing,and operational considerations, housing operators and

managers could identify agencies already working with the LGBTQIA+ community to

help then design inclusive practices and policies. Smaller organizations/programs that

Recommendation 3: LGBQTIA+ community housing

34

SUBSTANCE USE AND RECOVERY SERVICES PLAN

are more experienced in this area could also be utilized to create focused funding